By John Wukovits

The grimy, weary Marines heard with little emotion the instructions shouted by their officer. He wanted them to mount yet another charge to the top of the nondescript hill blocking their way, another collection of rock housing an enemy that tried to halt their advance. Yet, his words rang with a different resonance, a tone that stirred feelings the men assumed had lain dormant. “When we go up there,” barked the officer, “some of us are never going to come down again. You all know what hell it is on the top, but that hill’s got to be taken, and we’re going to do it. I’m going up to the top of Sugar Loaf Hill. Who’s coming along?”

With that brief oration, Major Henry A. Courtney, Jr., led 44 Marines in a bold charge that helped make the name Sugar Loaf synonymous with courage, ferocity, death, and gallantry. (Get regular stories about the Pacific Theater and the fighting that defined the Second World War inside WWII History magazine.)

The Buildup to the Okinawa Campaign

The Okinawa campaign had opened six weeks earlier with a calmness that starkly contrasted with the violence soon to be experienced by Courtney’s unit.

Marine Colonel Earl Landreth, accompanying assault Marines as an observer during the April 1, 1945, landing on Okinawa’s beaches, could hardly believe the dearth of opposition. Meticulously penciling notes in his small black-covered notebook as his craft surged closer to shore, Landreth marveled at the lack of enemy mortar shells and hail of machine gun bullets he assumed would by now be rapidly transforming the normally placid waters into a cauldron of death. Instead, only quiet greeted Landreth and the other Marines in his landing craft.

Planners selected the landing site, on Okinawa’s western coast near the village of Hagushi, because its width and mild surf offered an attractive entrance, and because the gradually rising terrain behind Hagushi opened toward two key airfields one mile back from the beaches. Marines braced for a brutal shoreline reception, similar to the ghastly spectacle at “Bloody Tarawa” 17 months earlier, through which they would have to fight every inch of the way simply to get to the beach.

A briefing officer at Ulithi laid it on the line for a group of Marine privates and corporals from the 1st Marine Division. PFC Eugene B. Sledge, who later wrote one of the classic memoirs to emerge from the Pacific Theater, recalled what the officer told the hushed group: “This is expected to be the costliest amphibious campaign of the war. We will be hitting an island about 350 miles from the Japs’ home islands, so you can expect them to fight with more determination than ever. We can expect 80 to 85 percent casualties on the beach.”

Sledge and the other young Marines sat in stunned silence, as if they were listening to their own obituaries. No operation to date had exacted such a frightful toll on its assaulting waves, yet they were being told that was what they should expect.

To reduce that gruesome casualty prediction, a prodigious weeklong bombardment of Okinawa opened on March 24, pouring more than 27,000 rounds of 5-inch or larger shells on Japanese positions. The maddening bombardment rattled enemy soldiers’ nerves and disrupted their sleep, prodding one irate Japanese to write angrily in his diary, “What the hell kind of bastards are they?” Despite the pounding, the Japanese suffered light casualties and few positions were reduced to rubble.

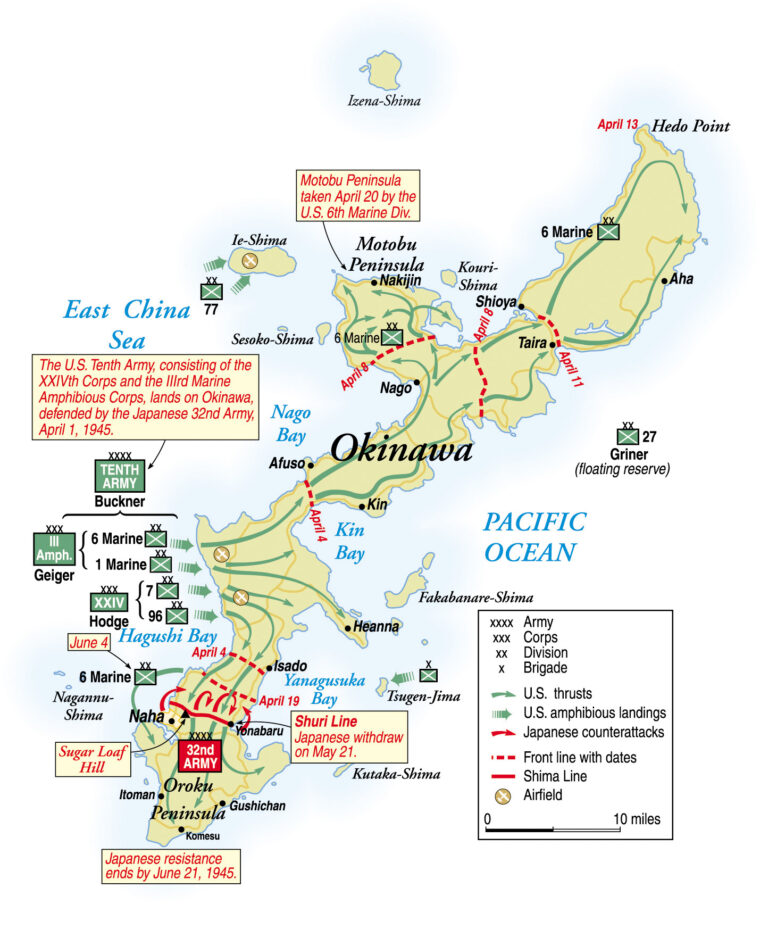

The bombardment was but one piece of the vast machine that gathered for the campaign, which marked the initial time that ground forces from Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s Central Pacific drive merged with General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific thrust. Over 180,000 troops comprised the Tenth Army, the designated unit ordered to seize Okinawa. Army Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner commanded seven divisions: four Army divisions under Maj. Gen. John Hodge and three Marine divisions—the 1st, 2nd, and 6th—under Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger.

The United States wanted Okinawa for three reasons. First, American-medium range bombers could strike the Japanese Home Islands from Okinawa, which rested a mere 360 miles southwest of Kyushu. Second, Military planners needed the island as a support base for the scheduled November invasion of the Home Islands. Finally, seizing Okinawa would sever the remaining supply lines from the resource-rich southwest to resource-starved Japan.

Mitsuru Ushijim’s Calm Leadership

Marines and Army infantry faced strong opposition from more than 100,000 troops of the 32nd Army and their invigorating commander, Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima, who fit few of the popular stereotypes circulating wartime America about Japanese officers. Thoughtful and quiet as opposed to barbaric and brash, Ushijima carved a successful military career before arriving at Okinawa, commanding an infantry unit in Burma as well as serving as commandant of the Japanese military academy at Zama.

The lean man sporting a large mustache bore himself with the pride of an ancient samurai warrior. His reputation for bravery under fire and his fatherly demeanor instilled not only confidence in those who served under him, but often love. He chatted with young soldiers and thanked volunteers who helped build fortifications, and while he handed great responsibilities to his staff, he accepted the blame whenever anything went wrong.

Shortly before the Americans rushed ashore, Ushijima delivered common-sense advice to his troops, not as a fiery coach might exhort his men during a halftime tirade, but more as a kindly mentor addressing his closest pupil.

“You must realize that material power usually overcomes spiritual power in the present war. The Americans are clearly our superiors in weaponry. Do not depend upon your spiritual power to overcome this enemy. Devise combat methods based upon mathematical precision, and then think about displaying your spiritual power.”

Few strategists, including Ushijima, doubted that Okinawa would fall to the Americans. If the Japanese could force their foe into a long, protracted campaign, however, maybe they could delay the inevitable invasion of the Japanese Home Islands until peace feelers succeeded or until some miracle saved Japan.

Ushijima Plan to Defend Okinawa

Ushijima knew his men would contest every yard of ground, for once Okinawa fell little remained to keep the United States off Japan’s doorstep. Ushijima correctly deduced that he could not halt the Americans on Okinawa’s beaches or on its relatively flat northern terrain, where American tanks and aircraft could inflict a ghastly toll. He instead decided to make his stand in the south, where the hilly terrain swung to his advantage and where he could make use of the port of Naha, Nakagusuku Bay, the large city of Shuri, and important airfields. Ushijima intended to allow American troops to land uncontested and advance inland, then wait until they veered to the south. There, on his terms and on ground more suitable to his forces, he planned to destroy the foe.

Unlike the flat northern region, ridges, draws, cliffs, and limestone caves dominate Okinawa’s southern third. Stretching along an east-west axis directly across the island, the undulating terrain chops Okinawa into a multi-ringed complex of natural fortification lines. Hills and 300-foot ridges look down on dirt roads that meander through valleys, fashioning perfect killing grounds for Ushijima’s soldiers and artillery when American units stepped along these routes.

Ushijima anchored three parallel defense lines on ancient Shuri Castle, which from its lofty hilltop position guarded the approaches to a six-mile-wide opening into southern Okinawa. From the castle, a western flank ran through the ridges toward Naha and the sea, while an eastern flank extended to the Yonabaru Airfield near the ocean. Intricate tunnel systems connected underground chambers, caves, and emplacements. Above ground, Okinawan burial vaults provided Ushijima with numerous miniature fortresses from which to oppose the Americans.

Ushijima intended to wear out the Americans by forcing them to assault each ridge and clear out every cave and burial vault. Protective trenches, bristling with troops laden with machine guns and knee mortars, stood in front of the ridges, while heavy machine-gun emplacements added their withering fire from the ridges behind. Mortars placed along the tops and reverse slopes and artillery fire directed from adjoining hills would contribute additional destructive power. When the units in the first line of defense could hold on no longer, Ushijma would pull them to a second line, where the Americans would have to repeat the same costly operations to again dislodge their enemy.

Ushijima hoped to separate American infantry from the tanks that supported them by directing intense artillery fire against the tanks, then dispatching Japanese soldiers with satchel charges and burning rags to approach the tanks in suicidal runs. Other infantry would shoot or bayonet American tank crews as they exited their burning vehicles. Murderous fire from hundreds of caves and gun emplacements would then decimate the exposed American infantry.

Ushijima placed two crack divisions, 24,000 troops from the 62nd and 24th Divisions, along the main defense line, backed by the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade, one tank regiment, 15,000 naval personnel, and 20,000 members from the Boeitai, the Okinawan home guard. Ushijima could also count on 3,500 men stationed in the Oroku Peninsula under Vice Admiral Minoru Ota a short distance behind the Shuri Line. Okinawa might fall, but at a price that would make the Americans think again about seizing Japanese-held soil.

Sugar Loaf Hill: Where Good Fortune Came to an End

Marines and Army forces did not know this as they prepared to hit the beaches on April 1. Some remarked on the “coincidence” of the attack occurring on April Fools’ Day. Others sensed irony in that it was also Easter Sunday, celebrated throughout the Christian world as a day of peace and redemption.

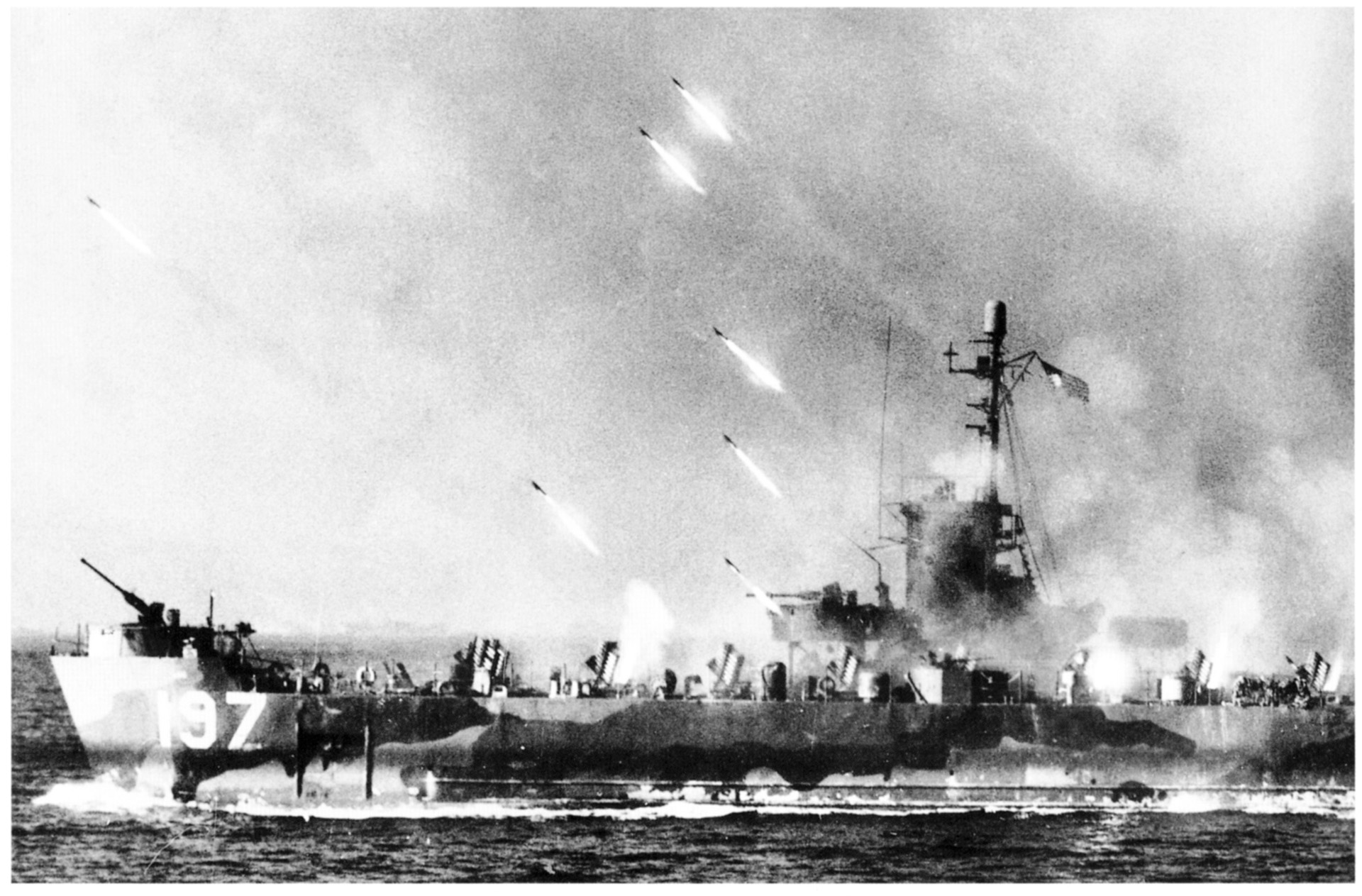

In a deafening pre-invasion bombardment, 42 ships and almost 200 gunboats inundated the area immediately behind Hagushi’s beaches with mammoth shells, while 500 naval aircraft crisscrossed the skies strafing the landing zones. As that hellish prelude ended, the 1st and 6th Marines smashed ashore on the northern edges of the beaches while the Army’s 7th and 96th Divisions hit the southern portion.

Private First Class Eugene Sledge read a sinister implication into the lack of opposition. If a strong Japanese presence existed on Okinawa, where were they? Sooner or later they would lash back with a vengeance. An unopposed landing simply meant bitter fighting someplace else, at a later date.

For a while, though, Marines took comfort that they remained alive. Their luck continued to hold as units advanced inland toward their first objectives.

“This is hard to believe,” wrote Time Magazine’s Pacific correspondent, Robert Sherrod, who had covered the Marine landings at Tarawa, Saipan, and Iwo Jima. Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, commander of the amphibious forces at Okinawa, jubilantly radioed his superior at Pearl Harbor, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, “I may be crazy but it looks like the Japanese have quit the war, at least in this sector.” A more sober Nimitz replied, “Delete all after ‘crazy.’”

By nightfall, 60,000 men and their supporting tanks, artillery, and supplies dug in on a beachhead 5,000 yards deep and 15,000 yards wide. The smooth drive across Ishikawa Isthmus continued the next day, when elements of the 1st Marine Division advanced within sight of Okinawa’s eastern coast. Marines secured the coast the following day, which severed Ushijima’s main element in the south from his men in northern Okinawa. In four days of rapid advance, American forces seized what planners had expected would take three weeks. “I’ve already lived longer than I thought I would,” remarked one relieved infantryman from the 7th Division.

Encouraged by the campaign’s surprising ease, Marines erected what they considered life’s amenities—mess halls, showers, and an outdoor motion picture screen. General Buckner sent the 1st and 6th Marines veering north, while the three Army divisions turned south to look for the enemy.

Sledge proved correct, though. Sooner or later the Marines’ good fortune had to end. One of the places it came to a crashing halt was a small mound of dirt bearing a fairytale name—Sugar Loaf Hill.

The Marines Encounter the Japanese

While the Marines located and engaged the enemy in the Motobu Peninsula in the north, their Army cohorts stalled in front of the first of Ushijima’s three defense lines in the Shuri region. Once the Marines completed their mission, Buckner brought them south to aid in puncturing the Shuri Line. The 6th Marine Division entered the lines against Ushijima’s western seaward flank, while the 1st relieved the weary Army 27th Infantry Division on the eastern flank. Buckner had divided the island into two combat zones, the Marine western half and the Army eastern half. Two crack foes stood opposite each other about to embark on a costly campaign staged on Okinawa’s rugged ridges.

While Marines moved into position along the Shuri Line, Japanese commanders debated their next step. A disastrous Japanese counterattack on May 3 forced Ushijima to withdraw his forces to the second of his defensive lines, an eight-mile path winding from Yonabaru on the east coast, through torturous ridges near Shuri Castle, on into the port of Naha on Okinawa’s western coast. The terrain along this line bore misnomers that sounded more like places out of theme parks. Chocolate Drop Hill, Zebra Hill, Sugar Hill, Wart Hill, and Sugar Loaf Hill dominated Ushijima’s second line, but their rugged land features, shrouding hundreds of Japanese machine guns and mortars, soon tested Marine and Army valor and transformed the childlike names into words synonymous with death, pain, and terror.

Buckner planned to throw 85,000 men in five divisions against this line, partly as a response to Nimitz’s pleas to speed up the ground operation so his ships could sooner depart the dangerous waters off Okinawa. While the 96th Infantry Division tried to swing around Ushijima’s eastern flank at Yonabaru and the 6th Marine Division plunged toward Naha, the Army’s 77th Infantry Division and the 1st Marine Division would advance in the middle toward Shuri Castle. If units turned either flank, they had orders to dash across Okinawa and trap Ushijima’s men.

Buckner’s Forces Run into the Fortifications at Sugar Loaf Hill

When Buckner’s general offensive opened at 7 am on May 11, the 3rd Battalion seized high ground near the Asato River that commanded a view of Naha. Delaying for a time an advance against the town, Marines swung south and east toward hilly terrain between Naha and Shuri, hoping to encircle Ushijima’s defense system. The astute Japanese commander had planned for such a move and placed a surprise directly in the path of the 6th Marine Division; the fortifications at Sugar Loaf Hill.

How could something so ordinary looking possibly cause such problems, wondered many 6th Division Marines as they approached Sugar Loaf, their objective. Shuri Heights, rising precipitously only a few hundred yards to their rear, appeared to dwarf what most Marines disregarded as a minor obstacle. A brief action, at most, might be needed before the division closed in on Ushijima’s central strongpoint at Shuri Castle.

The clay elevation hardly inspired terror. Sparsely dotted with shrubs and trees, Sugar Loaf’s 300 yards of frontage rose to only about 75 feet before leveling off into a thin crest. However, beneath its serene veneer, 2,000 Japanese defenders waited patiently to deliver deadly blows with hundreds of machine guns, mortars, grenades, and satchel charges, for the diminutive hill anchored the western end of Ushijima’s main defense line and stood as sentinel to both Naha and Shuri.

Combined with Horseshoe Hill to its south and Half Moon Hill to its southeast, Sugar Loaf stood as the point of a lethal arrow thrust from Shuri directly at the approaching Marines, who would be forced to advance across level terrain before even placing foot on one of the slopes. Ushijima, who intended to stymie his foe on the flat ground and the slopes, manned the trio of hills with fresh defenders from the 15th Independent Regiment of the 44th Brigade, led by Colonel Seiko Mita, and turned the elevations into intricate, tunneled complexes bristling with machine guns and mortar nests. The Japanese commander so intricately carved out his defenses that should American forces attack any one spot Shuri Heights artillery and converging fire from all three hills would tear into their ranks. Every foot of Sugar Loaf had been gridded and registered; every possible approach was covered. At the first sign of the enemy, the somnolent hill would boom to life with devastating gunfire that would decimate unsuspecting platoons and companies.

It did not take long for Sugar Loaf to stamp its imprint on the combatants. A weeklong pattern of strife on Sugar Loaf left Marines haggard and stunned. Through withering gunfire that depleted their ranks with each step, Marines advanced up the hill’s slopes or even rushed to Sugar Loaf’s crest, only to fall back in the face of ferocious opposition. Fifty men might reach the incline; fifteen would scurry back, bloodied and dazed.

Company G Reaches the Summit, Then Falls Back

Company G of the 22nd Regiment’s 2nd Battalion, commanded by Captain Owen T. Stebbins, kicked off seven days of agony with an infantry-tank assault on the afternoon of May 12. Confident that a speedy operation lay before them, Company G encountered minimal gunfire in its first 900 yards. Suddenly, all hell broke loose as small arms fire, machine guns, mortars, and artillery ripped into their ranks and pinned down two of the three platoons before reaching Sugar Loaf’s slopes. Captain Stebbins and Lieutenant Dale W. Bair led 40 men of the remaining platoon toward the hill, but before they advanced 100 yards, 28 Marines fell to Japanese gunfire.

Stebbins collapsed when machine-gun bullets riddled his legs. Bair assumed command, but before he could shout his first order, Japanese bullets shredded his left arm. With the limb hanging useless, Bair gathered 25 Marines and, after grabbing a light machine gun with his good hand, resumed the attack. Upon reaching Sugar Loaf’s crest with 10 men, the six-foot, two-inch tall, 225-pound officer boldly stood atop the hill and sprayed the enemy with machine-gun fire.

Bair’s total disdain for danger stirred his men. One Marine stated, “It was impossible to be afraid when you saw him standing up there.” Sergeant Edmund DeMar claimed Bair looked like a Hollywood actor in those popular war movies where a solitary soldier fires courageously at a swarm of enemy. “And what a sight he was, standing there, all alone, at the top of Sugar Loaf.”

Two more bullets slammed into Bair before he went down. One tore a chunk of flesh out of his leg, and the other ripped away a portion of his buttocks. DeMar, bleeding profusely from a thigh wound, saw nothing but dead or wounded Marines all about him. In the midst of the carnage and noise, one sound haunted DeMar. A young Marine, wounded and frightened, cried for his mother and father.

The dwindling number of survivors on the hot summit realized they had to abandon Sugar Loaf to avoid annihilation. Under cover of a protective smoke screen, Marines started crawling down the slopes toward their lines. DeMar, who labeled the predicament on Sugar Loaf a “screwed-up mess,” told another Marine who evinced concern over DeMar’s wounds that he would “crawl all the way to Madison, Connecticut, if I have to.”

After a short distance, a tank driver lifted DeMar to the top of his vehicle, where he applied a bandage to the wound, but he, too, fell to enemy gunfire and slumped unconscious beside DeMar. As the tank lumbered cautiously down the hostile, smoke-enveloped slopes, the injured driver’s blood trickled onto DeMar.

“What a ride!” declared DeMar. “I was covered with blood, a lot from my leg wound and a tremendous amount from the tanker. We must have looked like something out of a horror movie.”

Company G repeatedly stormed Sugar Loaf throughout May 12, even seizing its summit on three occasions, but each time Japanese mortars and hand grenades drove them back. When nightfall arrived, the hill remained in Japanese hands, while Marines tended to their wounded. DeMar’s platoon suffered 50 percent casualties, while only 75 of 215 men in Company G were able to man their posts that night. The most demoralizing aspect was that, despite the appalling losses, Marines faced further attempts in the days to come. Sugar Loaf had to be taken, which meant that more young Americans would perish.

Marines repeated the gruesome pattern over the next six days. Elements of the 22nd Regiment again reached Sugar Loaf’s summit on May 13, but artillery fire from Shuri Heights and potent Japanese counterattacks again drove them off.

Courtney’s Charge

Both the 22nd and 29th Regiments attacked the hill the next day. Two companies of Marines gained the summit by early afternoon, but heavy enfilading fire forced them back down. The commander of the 2nd Battalion, Lt. Col. Horatio C. Woodhouse, Jr., ordered a late afternoon assault which stalled on Sugar Loaf’s slopes and stranded 44 Marines amid punishing fire that killed or wounded more than a hundred fellow Marines.

As Japanese soldiers rolled hand grenades from Sugar Loaf’s summit down on the Marines below, Major Henry A. Courtney, Jr., the 2nd Battalion’s executive officer, rallied the small group of attackers with stirring words and bold example. Angry about being caught on Sugar Loaf’s slope, Courtney figured he and his men stood in one of those desperate situations men in combat sometimes find themselves where, since they were too weak to defend their position, they may as well attack.

“Men,” Courtney began, “if we don’t take the top of this hill tonight, the Japs will be down here to drive us away in the morning.” He explained that when they reached the summit, he wanted every man to throw as many hand grenades as he could to pin down the enemy, then dig in for a long stay. After radioing for mortar support, Courtney asked for volunteers to go with him.

Courtney started up with 44 Marines, hurling grenades into caves as he hustled by. Once at the top, Courtney’s group dug in for what they knew would be a bloody nighttime slugfest for control of Sugar Loaf. Enemy soldiers, masked by the darkness, crawled so close to Courtney’s crude perimeter that Marines could hear the Japanese grunt as they heaved grenades up at them. Around midnight, Courtney perceived movement on the Japanese-controlled side that alerted him to a possible banzai charge. Before the enemy could attack, Courtney hurriedly organized his men and launched a hasty preemptive strike over Sugar Loaf’s crest.

The dangerous move, possibly considered foolish in calmer struggles and safer climes, became typical on Sugar Loaf, where men took risks they normally might never ponder. One Marine who witnessed the attack later said, “Oh, I think he [Courtney] might have gone a little wacky but, you know, that happens. It seems like you’d spend an eternity trying to take a place like Sugar Loaf, watching so many of your buddies getting shot up so badly. Then you think the hell with it and you do something you wouldn’t normally do.”

As Courtney and his ragged band drove the Japanese back, a hand grenade exploded near Courtney that inflicted a fatal neck wound on the brave leader. Marines, upset at the loss of their commander, covered Courtney’s body with a poncho and continued battling to hold their position, but as the long night wore on, mortars and sniper fire reduced the number of able Marines to 15. Sadly, the next morning they once again yielded Sugar Loaf’s crest.

A Counterattack Leads to Hand-to-Hand Combat

A Japanese counterattack on at 7:30 am May 15 forced the few remaining Marines off Sugar Loaf and crashed into Marine lines at the hill’s base, where the battered 2nd Battalion fought bitterly to stem the attack. Six hours of hand-to-hand combat produced valiant scenes. Wounded Corporal John A. Spazzaferro maintained his fire until he killed the Japanese who shot him, then slumped a short distance from his injured platoon leader, Lieutenant Edgar C. Greene. The two, out of contact with the rest of the Marines, lay as still as possible to fool the Japanese that swarmed on all sides. With eyes shut tight and hearts pounding, they heard four enemy soldiers approach. One stepped toward Greene, removed his wristwatch, then reached into Greene’s jacket pocket in search of any valuables. The Japanese quickly yanked his hand back out when he felt a sticky substance—Greene’s blood—and rushed away to clean it off. Greene and Spazzaferro lay still for an entire day in Japanese-held territory until the Marine line again reached them and they could be evacuated.

The brutal fighting shocked even veteran Marines. Private Dean Klingenhagen, pinned down by heavy mortar and machine-gun fire, heard a muffled explosion behind him. He turned to see the blackened, almost unrecognizable body of his platoon leader, who had been hit directly by a mortar shell. In moments another Marine, moaning in pain, crawled by Klingenhagen with his right foot blown off.

The Americans battled for 10 hours to halt the Japanese counterattack. Marines lobbed so many hand grenades at the enemy that part of the terrain on which they battled was labeled Hand Grenade Ridge. Corporal Jack Castignola worked with machine-like precision, pulling the pin of one grenade and rolling it down on the enemy while reaching for another. Castignola, a future high school state champion football coach, also shot and killed a huge enemy soldier who “would have made a good end on any football team.” Over six feet tall and weighing more than 200 pounds, the Japanese soldier walked near Marine lines, dressed in a Marine uniform to disguise his identity. At first Castignola paid little attention, but then he noticed the man’s long rifle and unusual helmet—telltale signs of a Japanese. “He sagged like a loose rope the first time I shot,” recalled Castignola.

In three days of fighting, the 22nd Regiment suffered a 60 percent casualty rate. Its 2nd Battalion alone lost more than 400 men, requiring superiors to replace it with the 3rd Battalion. In spite of the carnage, the Marines held their positions through thunderous artillery and mortar fire the night of May 15-16.

The Marines renewed their assault on Sugar Loaf at 8:30 am on May 16, the fifth straight day of ebb and flow combat. While the 29th Regiment scaled partially up Half Moon, the 22nd focused on Sugar Loaf. Supported by covering fire from the 29th, a battalion of Marines edged around Sugar Loaf’s left side late in the afternoon in hopes of dashing up the slopes but ran into devastating enemy fire, including artillery from Shuri Heights, that pounded their left flank and rear. Four separate times Marines rushed up to gain Sugar Loaf’s summit. Four separate times they withdrew.

Combat correspondent Elvis Lane viewed the carnage at Sugar Loaf and wrote, “Corpses litter the gray, muddy landscape. There are numerous severed arms and legs. And an occasional head. I wonder how many besides me are trying not to look at the dead. Some of the corpses seem to be grinning. The flesh has rotted away from the skull and the teeth are bared. I am afraid that if I stare, one of these grinning dead might ask: ‘Don’t you belong with us?’ And another might make this monstrous prediction: ‘The war isn’t over! You’ll soon be joining us!’”

The macabre drill—up the slopes, back down the slopes, more Marine dead littering the ground—continued the next morning, but this time a noticeable crack finally appeared in Ushijima’s defenses. After an effective one-two combination of a heavy battleship bombardment followed by carrier-based air strikes, 6th Division commander Maj. Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd moved the 29th Regiment through a small depression running east of Sugar Loaf. Once safely through, the regiment split into two forces and attacked Sugar Loaf and Half Moon. One company rushed Sugar Loaf’s eastern slope and reached the top, but another fierce counterattack toppled the Marines back down the slope.

The company commander, Captain Alan Meissner, ordered his men to fix bayonets and took them to the top again, but he also had to pull back in the face of savage hand-to-hand fighting. After a third attempt failed, frustrated Marines finally reached the summit late in the afternoon and successfully repelled a counterattack. They dug in to hold the crest, but in a cruel twist of fate the Marines ran out of ammunition. After suffering 160 casualties, the Marines had to again yield the crest.

On the positive side, a battalion seized a large section of Half Moon Hill, which meant that Marines could count on increased fire support for the next day’s attempt. General Shepherd saw an opportunity to conclude the nasty business at Sugar Loaf.

Finally, Sugar Loaf is Taken

An intricate ruse worked to perfection on May 18. The commander of D Company, 29th Regiment, Captain Howard L. Mabie, sent a group of Marines against Half Moon and Horseshoe to divert enemy machine-gun and mortar fire away from Sugar Loaf. While the Japanese turned their weapons on this group, a second force of Marines, backed by tanks, hit Sugar Loaf’s right flank. As the Japanese defenders shifted men to that sector, Mabie dispatched a third group of men and tanks around the left flank to Sugar Loaf’s rear, then sent 80 men under 1st Lt. Francis X. Smith up the forward slope. When Smith and his men reached the summit, they tossed grenades on the Japanese from above while Mabie’s tanks fired point-blank from below.

Ushijima’s defenders had no choice but to either abandon their positions with near suicidal retreats through the Marines, or to rush the Americans with banzai efforts. One group streaked out of a cave, explosives strapped to their backs, but quickly disappeared in a violent explosion when Marine machine gun bullets ignited the satchel charges. While this occurred, Marines gunned down fleeing Japanese with abandon. Lieutenant Donald R. Pinnow watched while “the Japs began running down from the crest. There must have been 150 of them. We fired and blew them all over the landscape.”

Those actions ended the fight for Sugar Loaf, which finally fell silent after so many days of chaos. Weary Marines maintained a tight vigil, but after seven maddening days the scarred, churned elevation was theirs. Fighting for what had at first appeared to be a harmless accumulation of dirt and rock, 6th Division Marines suffered 2,662 men killed or wounded. They lost another 1,289 men evacuated because of either exhaustion or battle fatigue. Although Ushijima continued to harass the Marines until both Horseshoe and Half Moon Hills were secured, Marines never again relinquished their hold on Sugar Loaf.

Correspondent Lane’s reaction typified how privates and captains, corporals and majors felt now that they had survived the weeklong bloodbath. Lane thought that the fighting on Sugar Loaf “must be the bloodiest triumph in Corps history. Thank God there are no signs, none whatsoever, that the enemy is again rushing troops to try and recapture this hill. I’ve lost count of how many times Sugar Loaf was seized by us, by them, and how many days we’ve been here. The silence convinces us that Sugar Loaf really does belong to the 29th.”

John Wukovits is the author of Pacific Alamo, the story of the battle for Wake Island. He has previously written Devotion To Duty, a biography of Admiral Clifton A.F. Sprague, hero of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, published by the Naval Institute Press.

Husband, Army vet was assigned to Tori Station as a member of NSA. Made many TDYs all over the western Pacific and apparently to many other places and activities that only came out during outbursts in nursing home which were diagnosed by a psychiatrist and doctor as PTSD, not hallucinations. Whatever he did sounded violent and combative. Anyway, we lived, before government housing became available , on the economy down the road from Shuri Castle. We visited it as tourists. I was only 26 years old in 1963 and had heard of the battle of Okinawa, of course but had NO idea what that meant as I walked what I have learned was the bloodied, hallowed grounds. I have watched the battle from different perspectives on the history channel and now just read this article which has left me numb, It is probably not different from other Pacific battles, but for the length of time or the number of casualties on one hill, perhaps that is why I guess it is one of the Marines greatest battles. It is beyond me how men continue to fight under such conditions. Thank god they stopped this enemy as they did in Europe or what a world this would be. I am humbly greatfull for my time there which has brought to me an understanding of how the sacrifices made by so many allowed me to stand there as a young woman. Thank you to all who served, survived and so many who did not. I am old now but only because, in the long run, for what all who fought during WW II and am still speaking English and not German or Japanese !

My grandfather’s cousin and grandmother’s brother were both there in the 29th. Uncle Jack was wounded April 16 throwing back an enemy grenade, he wrote to his father that he was mostly worried they wouldn’t let him get back in the fight. Cousin Sherm was killed May 17.