By Michael D. Hull

Allied fortunes were at a low ebb as strategic British and American bases fell like ninepins to the Japanese across the Far East in the early months of 1942.

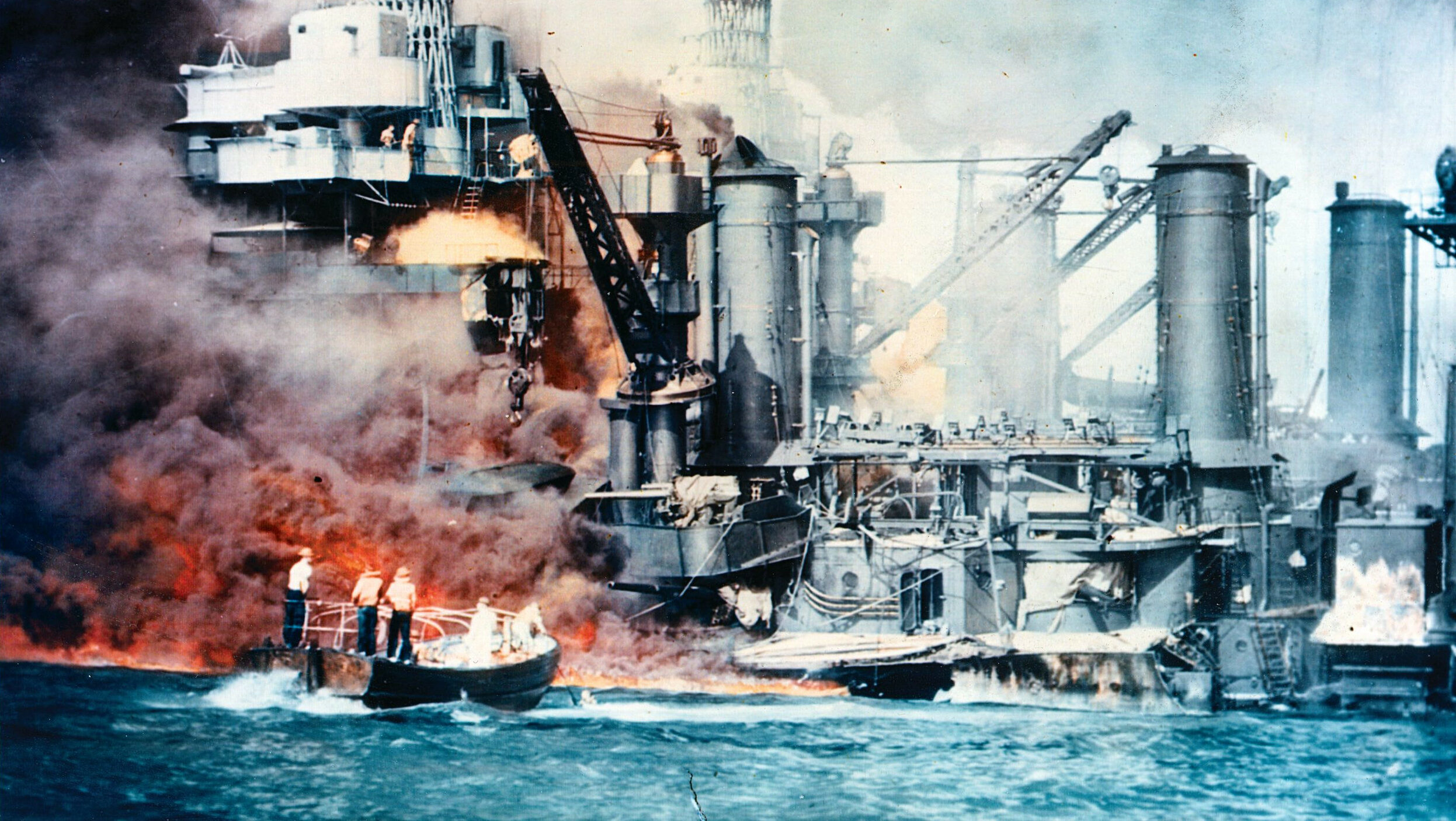

At anchor in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the U.S. Pacific Fleet had been crippled by carrier planes of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The “impregnable” British base at Singapore had fallen. Valiant but poorly trained and equipped American and Filipino troops were falling back in the Philippine Islands, and the Royal Navy battleship HMS Prince of Wales and

battlecruiser HMS Repulse had been sunk by airplanes off Malaya.

In the Dutch East Indies in early February 1942, under-strength Allied naval forces were mauled by the Japanese navy, while ground units of the empire advanced to Sumatra and invaded Bali. Between the two islands lay the Dutch colony of Java, its wealth of rice, rubber, and oil resources a magnet to the Japanese. The gallant Dutch had vowed never to surrender the sprawling, lush island, but the enemy was getting close, and the Dutch, American, British, and Australian military and diplomatic authorities there were anxious.

The U.S. Asiatic Fleet shifted its headquarters from Surabaya on the northern coast of Java to Tjilatjap on the southern coast. Rumors swept the island during the week after Singapore fell. Reportedly, the Japanese had landed on the northern coast. Paratroops had supposedly dropped and were hiding in the hills. Dutch officials, some said, were preparing to evacuate.

Among the Allied servicemen in Java that tense month of February 1942 were 41 American sailors at a small Dutch hospital in the thick jungle of the Javanese interior. They were wounded survivors of the light cruiser USS Marblehead and the heavy cruiser USS Houston, severely damaged on February 4 by a Japanese armada in the Makassar Strait off Balikpapan, Borneo. As part of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Fleet under Dutch Rear Admiral Karel W. Doorman based at Surabaya, the Marblehead and Houston had been attacked that morning by 54 enemy bombers. The two damaged ships had been forced to retire from the battle area, the Houston limping south to Australia and the Marblehead putting in at Tjilatjap on February 6.

Lying in their cots and being tended by caring, efficient Dutch doctors and nurses, the bluejackets from the two cruisers were not told of the rumors rife in Java. But they knew the enemy was not far away and that the Red Cross was no guarantee against Japanese butchery. Wounded British soldiers had told them grim stories of what happened after the fall of Singapore.

Dr. Wassell Moves Wounded Sailors to Tjilatjap

There was another American in that hospital who was also uneasy. He was 58-year-old Navy Lt. Cmdr. Corydon McAlmont Wassell, a former Arkansas country doctor and medical missionary who had been the chief naval medical officer at Surabaya until ordered to come to the up-country hospital to act as liaison officer between the wounded sailors and the Dutch doctors. This assignment was to prove the toughest—and most rewarding—in his long career of medical practice and research in Arkansas and China. An unassuming man with a slow drawl, Dr. Wassell knew that somehow he had to move the men in his care to safety, hopefully in Australia.

He tried several times to telephone the navy headquarters in Tjilatjap but was unable to get through. Once, he did make a connection but was yelled at and told not to ask questions to which no one knew the answer. Unperturbed, he regularly toured the hospital wards and told the sailors to be patient. Things would turn out all right, somehow.

Then, the headquarters called Wassell and told him to get his less seriously wounded cases ready for evacuation. He was ordered to bring everyone who could stand a rough sea passage. There was urgency in the voice on the other end of the line. Wassell did not tell the men that night because he felt they would be too excited to sleep. An eight-hour train ride to the Java coast would be arduous enough.

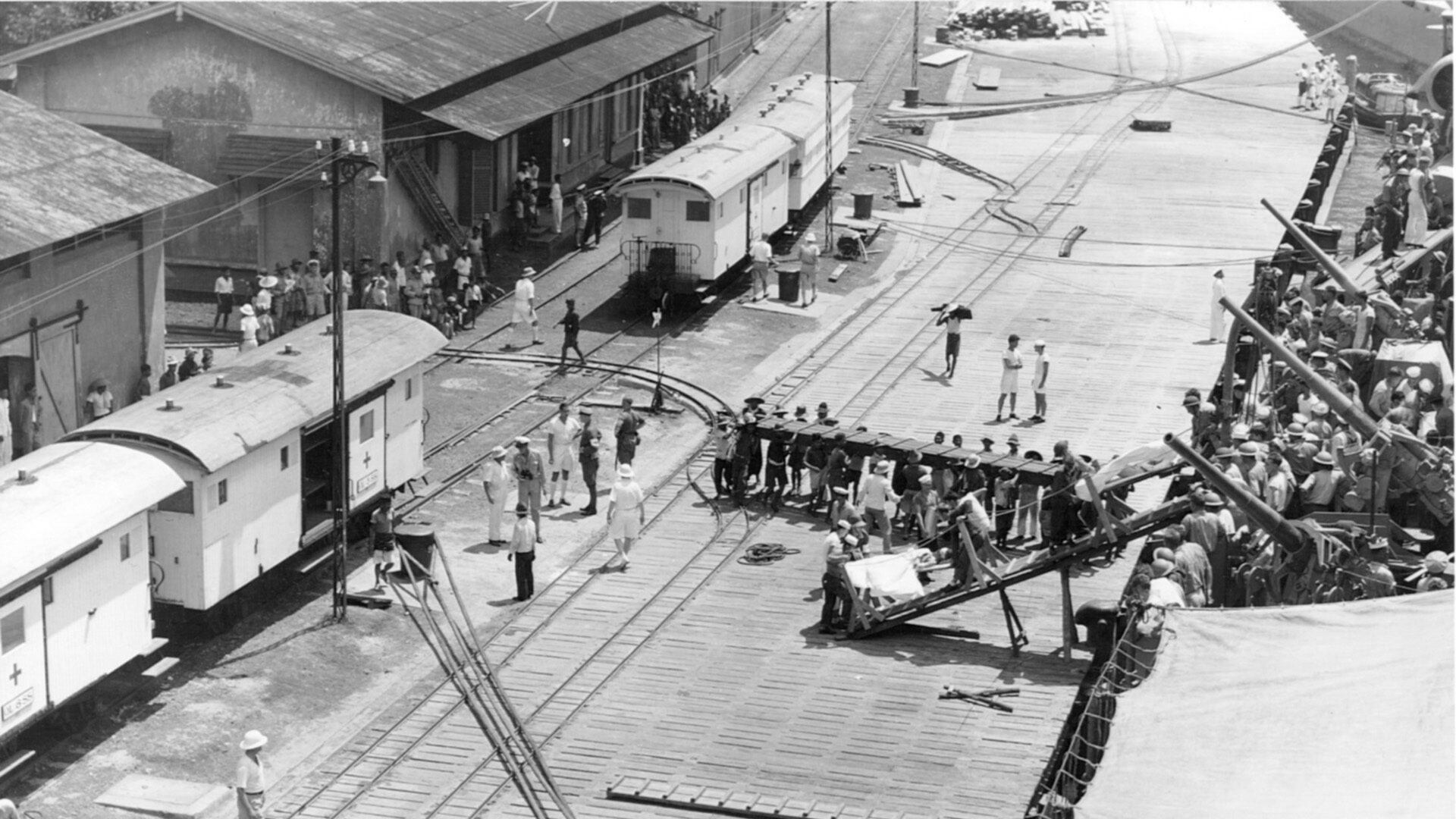

Soon after dawn, Wassell informed the sailors. Until 10 am, he rushed around preparing for their departure. Each patient had to be officially released by the methodical Dutch doctors. When the 41 bluejackets were loaded aboard ambulances to head for the local railway station, the entire hospital staff stood and waved. The chief Dutch doctor wished them bon voyage, and Wassell declared that he would never forget the kindness of the Dutch and Javanese.

The American doctor and his charges then began the journey back to Tjilatjap, the port to which the sailors had come after their ordeal in the Makassar Strait. The 50-mile journey was slow, and the stifling heat became more intense as the train chugged down to the coastal plain. During its frequent stops, Wassell dashed outside to buy food and drinks for his men. The train was delayed for an hour at one station because of an air raid alert.

When the train finally rolled into the Tjilatjap terminal, Wassell tried to reassure the sailors, exhausted from their journey. He told them to try and appear to be in better condition than they actually were. If they looked too sick, they would not be taken aboard ship because they would be too much of a burden if the vessel were attacked at sea.

Wassell Gets Some of the Wounded onto the Breskens

Tjilatjap was a mass of humanity. The railway station and the town swarmed with Dutch and British troops, refugees from the interior, and local officials trying to keep order. There was confusion, but no panic.

Wassell assembled his men on a hotel terrace and went to find a ship that would accommodate them. He located the navy headquarters on the crowded dock and was told to bring his sailors there immediately. He did so, shepherding them to the waterfront, where several Dutch steamers waited to sail at nightfall. Most of them were already crammed with passengers. The wounded sailors waited patiently near one of the largest vessels, the Breskens. The sun blazed down, and there was no shade on the dock for the stretcher cases. A Dutch officer standing on the gangway of the Breskens demanded a permit, which Wassell did not have. His navy papers were waved aside, and he was told to talk to a captain in one of the dock offices.

Struggling through the crowds, the doctor bumped into a high-ranking U.S. naval officer – the one he had talked to by telephone the previous night. He offered to help Wassell get his men aboard the Breskens until he saw the pathetic looking sailors on stretchers. The officer told the doctor that he would have to take them back to the hospital in the interior because they would have no chance if the steamer were torpedoed. But he did help the walking wounded get aboard the Breskens.

Back to the Interior with the Badly Wounded

Wassell was downcast, but he had no alternative. Waving farewell to his walking wounded, he had the stretcher cases reloaded on the ambulances for the return to the railway station. The hospital train had already left, but the resourceful Arkansan persuaded the Javanese authorities to couple an extra boxcar to another train that was about to depart for the interior. The stretcher cases were loaded aboard, and the train puffed out of the station, rattling through the countryside on a cool night.

It was a sad journey, and the sailors did little talking. Wassell was discouraged, but he refused to show his feelings to them. During a brief delay at a junction, he telephoned the hospital and told the chief doctor that he was returning with nine sailors – eight on stretchers and one of the walking wounded who had wandered off in Tjilatjap for a few beers and a tryst with a pretty Javanese girl.

The train rolled on. Puffing a cigarette in a long white holder, Wassell watched the sleeping sailors and realized that they were his men now, and not just a few stragglers. They mattered to him, and he pledged to get them to safety whatever the odds. Corydon Wassell mused about his earlier life and what had brought him all the way to Java.

Wassell Before the War

The doctor was born on July 4, 1884, in Little Rock, the son of Albert and Leona (McAlmont) Wassell. The family had immigrated from Kidderminster in the English Midlands. After earning a medical degree from the University of Arkansas in 1909 and completing postgraduate courses in internal medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, young Corydon started practicing as a doctor in the village of Tillar in Drew County, Ark. It was a hard life with few material rewards, but that did not matter to the young idealist whose singular purpose in life was to help others. He worked among poor tenant farmers and sharecroppers, and organized a group medicine plan for black field workers. Wassell married a young village teacher.

One day in 1913, the country doctor went to the Tillar Episcopal Church to hear the president of Suchow University in China speak about the needs of his countrymen. Wassell felt a compulsion to go to China. His wife supported him, and a few months later they were on their way to the Far East as medical missionaries. They set up home in Wuchang on the Yangtze River. Wassell worked there in the Boone University Hospital, studied Chinese, and became a father. His medical skills and compassionate approach were soon well known, and by 1918 he was in charge of the Chinese National Red Cross. The Wassells’ fourth child was born in Little Rock during a brief leave in 1919.

In 1921, Wassell found himself heading International Red Cross relief efforts after the Han River levee break and during the subsequent famine. He studied neurology, served as a professor of parasitology in Changsha, published articles on encephalitis, and did pioneering research on amoebic dysentery. Through tireless field work in some of the most remote and backward areas of China, he discovered the source of a plague that was ravaging the people. From 1923 through 1927, he served as the port medical officer and maritime medical officer at Kiukiang and also found time to run a private practice and consult at a Roman Catholic hospital. His wife died, and Wassell later married a missionary nurse, Madeline Day, of Englewood, N.J.

Meanwhile, the energetic doctor had been appointed a lieutenant junior grade in the U.S. Naval Reserve Medical Corps in 1924. He was promoted to lieutenant two years later. During 1927, he was on unpaid active duty with the gunboats of the famed Yangtze River Patrol, and that same year he returned to Little Rock for another stint at private practice. Soon, however, he found himself back in public service. Wassell was a public health unit director in Caldwell Parish, La., and Pulaski County, Ark., and spent six years as health director of the Little Rock schools.

Wassell championed public health systems, particularly affordable diphtheria immunization. During the Great Depression, he was given the task of battling malaria at camps of the Roosevelt administration’s new Civilian Conservation Corps. Based at St. Charles, Ark., he supervised the control of malaria at seven CCC camps from 1936 to 1938.

The U.S. Navy had not forgotten Corydon Wassell. He resumed regular commissioned duty at the age of 52 in 1936, and was called to active duty in 1940 when the CCC was disbanded. He served on a submarine inspection board at the Key West Naval Station in Florida, and in September 1941 was ordered to the naval base at Cavite in the Philippines. Wassell was scheduled to sail on December 7, 1941, but his departure was delayed because of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He was assigned instead to Java to take over as the chief medical officer at the Surabaya Navy Base. He arrived there in January 1942.

A Plane Ride Falls Through

Now, Wassell and his nine dispirited patients rode the train back into the Javanese interior. There was no way of knowing if they could reach Australia or if they would be trapped by the advancing Japanese. Arriving at the hospital just after dawn, Wassell and the sailors were welcomed by nurses with sherry, tea, and cakes. They could now hear the rumble of distant explosions, and the American doctor learned from his Dutch colleagues that Tjilatjap had been bombed during the night and several ships sunk.

While his men slept, Wassell put through a call to an airfield three miles away where some British and U.S. planes were based. An American major told him to call back in an hour. The doctor did so and was told that there would be room for him and his charges on the 13th and last plane leaving the field. They were to take no luggage—not even a razor blade—and should be ready at an hour’s notice.

Later that day, Japanese planes strafed the area, and concussions shook the little hospital. As heavy chunks of plaster dropped from the ward ceilings, the sailors took refuge under their beds, smoking and giggling with the nurses while trying to stay calm. The next morning, a wounded British soldier was wheeled into the sailors’ ward from the operating room, where he had had two machine gun bullets extracted from his legs. Asking Wassell for a cigarette, the Tommy said he had been hit during an attack on the airfield. The doctor was informed by telephone later that one of the 13 planes had been damaged and there would be no room for his wounded sailors. Again, he hid his disappointment from them.

Unable to sleep that night, Wassell heard an urgent knock on the door of his quarters. It was the chief Dutch doctor, who told him, “The enemy has landed on Java!” There was now no time to lose, but what could Wassell do? He tried unsuccessfully for an hour to telephone Tjilatjap, and then, without waking his men, wandered outside. He walked into the nearby town, where crowds were gathering at street corners. He sensed tension in the air.

Back to Tjilatjap

The American doctor strolled around in the night, his spirits flagging. Just before dawn, several dusty military staff cars and trucks rumbled into the town and drew up in front of the busy Grand Hotel. It was the advance guard of a retreating British Army convoy. Wassell’s hopes rose once more. He pursued the commanding officer, an aloof and languid man, who entered the hotel to ask where he could buy food and supplies. Wassell asked if the convoy was bound for Tjilatjap. Told that it was, Wassell asked if he and his nine wounded men could ride along.

The British officer agreed readily and told Wassell to bring his men there within two hours. Dashing back to the hospital, the doctor awakened the sailors and told them that the British convoy was probably their last chance to get out of Java. Meanwhile, he managed to get through by telephone to Tjilatjap and was told that there were still some ships there. The sailors were enthusiastic about returning to the coast. “Good for you, boys,” said Wassell. “Let’s get going!”

Without delay, the nine sailors and their guardian angel joined the British convoy. The worst cases were loaded into an old Ford car, and the rest rode in a truck. Wassell took the steering wheel of the Ford, although he had not driven for several years. Before the sun was high, the long convoy—staff cars, 200 supply trucks, wheeled antiaircraft guns, field kitchens, and mobile repair trucks—rolled out of the town. This was it. Wassell and his bluejackets were on their way again.

The vehicles were spaced out to minimize the possibility of air attacks, and everyone was told to jump out and take cover if Japanese planes appeared. Wassell wrestled with the old Ford over twisting, narrow country roads, threading his way past Dutch vehicles and Javanese ox carts. When the convoy occasionally made a halt, the British soldiers shared their bully beef, chocolate bars, and brewed tea with the American sailors.

The convoy rumbled on into the night, easing over bridges that had been mined to hamper the approaching Japanese. The vehicles snaked across a long suspension bridge over a river, and Wassell handed out scotch whiskey to Dutch and Javanese guards as they scrutinized every vehicle and its occupants. Then, in the middle of the night, Wassell and his men found themselves back in Tjilatjap.

Escape on the Janssens

The tireless doctor went into a crowded hotel, procured some food and beer for his men, and managed to find a room for them. A Dutch officer told Wassell that he would help him find a ship the following morning. As a dawn sea mist drifted in and enemy planes droned high above the port, Wassell hired a Javanese launch and rode out to one of two ships anchored in the Tjilatjap harbor. She was the Janssens, a small inter-island steamer.

The doctor clambered aboard and found that the captain was not eager to ferry wounded American sailors. Wassell pleaded his case emphatically, and the captain reluctantly agreed, although there was no sick bay, and no medical supplies were aboard, the captain warned, and the doctor would be solely responsible for his men.

Rushing back to shore excitedly, Wassell learned that his party had been depleted to seven men. One sailor had gone on ahead with a British evacuation officer, and another had been left at a medical aid station because he was too ill to continue. At dusk and under heavy rain that day, Wassell and some British soldiers carried the seven Marblehead sailors piggyback fashion aboard the Janssens. She was crowded, but the doctor found space for his men’s mattresses under an awning on the stern deck.

It was dark when the laden little steamer nosed out of the harbor, zigzagging through a minefield to the open sea. Wassell gazed back for the last time toward Tjilatjap, where British troops were setting up antiaircraft batteries on the pier. They had been ordered to make a last stand, and the American doctor felt sad because he knew they had little chance of survival against the superior Japanese forces now pushing across Java.

Into the night, the Janssens butted through the sea and the rain. She had been built for 200 passengers but now carried twice that number. Designed for 11 knots, her diesel engine could only labor along at seven and a half.

Wassell and his seven men relaxed for the first time since leaving the Dutch hospital. They were finally on their way to freedom, and the threat of enemy submarines, surface ships, and airplanes did not shake their spirits. The steamer headed due east, through the night and into the next day, which dawned bright and cloudless. The wounded sailors felt better after a night’s sleep on the cool deck, and the food aboard the Janssens was ample.

Wassell brought beer to the sailors, and some of them took a faltering walk on the deck. The steamer was crammed with refugees of various nationalities—Dutch, Javanese, Australian, British, and American. Some of them offered to give up their cabins to the wounded sailors, but the weather was warm and their doctor felt they were better off on deck—and they were closer to the lifeboats.

Strafed by Japanese Zero Fighters

The Janssens forged on as Dutch sailors manned small guns on the bow and stern and 30-cal. machine guns on each side of the bridge. The sailors strained their eyes across the empty sea for any sign of the enemy. Wassell was pouring himself a drink with a correspondent in the smoke room when he suddenly heard a commotion on deck. “Planes!” someone shouted. The doctor and the other men in the smoke room crawled under tables as three Japanese Zero fighters dived toward the Janssens. They had been escorting bombers from Bali to Tjilatjap when their leader had spotted the steamer.

The doctor struggled to reach his men on deck but was unable to force his way through the frantic crowd of passengers below. The enemy planes roared down at 300 miles an hour, machine guns chattering, and raked the steamer from bow to stern again and again. The Dutch gunners tried desperately to hit the three raiders, and the captain zigzagged the ship. The gun crews ran out of ammunition. Then, after several more passes against the steamer, the Japanese planes sheered off and flew away. It was almost a miracle; only 10 people aboard—most of them gunners—had been injured, and the steamer had suffered no serious damage. Rushing topside, Wassell was relieved to find his men unharmed.

The wounded gunners were carried into the ship’s bar, where there was a first aid cabinet. Wassell, who had not practiced any serious surgery for many years, rolled up his sleeves and went to work immediately. With only some morphine, iodine, bandages, and splints at hand, he and a Dutch pharmacist’s mate did what they could for the gunners.

Meanwhile, everyone aboard feared that the Japanese would return, and many passengers pressed the captain to put them ashore where their chances of survival might be better. So, three hours after the attack the Janssens put in at a little island inlet, and a lifeboat carried some passengers and crewmen ashore. Several of the passengers were women and children. All were sure that the little steamer was doomed.

Will the Janssens Make it to Australia?

The Janssens stayed in the inlet for four hours, during which food and water was taken aboard and the damaged lifeboats repaired. Wassell and his men agreed to stay aboard and try their luck at reaching Australia. The captain waited for nightfall, and when the moon rose the steamer headed back out to sea. A bright, full moon etched the outline of the vessel on the smooth water. There was not a ripple of wind. The men aboard the Janssens were apprehensive, sure they would be spotted by the enemy.

The steamer pressed on. With more room aboard now, Wassell moved into a cabin with a Dutch chaplain. The seven wounded bluejackets chose to stay on deck. Later that night, the captain announced that the Janssens had turned due south and, if all went well, would reach Australia in 10 days. Because of his depleted complement, the skipper ordered every able-bodied man to help with the chores and watches. Wassell and the Dutch padre set to work with mops and pails in the smoke room. Before turning in that night, both men knelt by their bunks and prayed for a safe journey and a speedy end to the war.

The little steamer chugged on southward through the moonlit night and day after day, with no sign of land. Her fearful occupants peered across the vast, empty ocean for a speck on the horizon or in the sky that could mean trouble, but there was nothing. Their luck held, and finally, after 10 grueling days, the Australian shore was sighted. Hearts soared and shouts went up, and the Janssens slipped into Fremantle harbor on the southwestern coast. The long odyssey of Wassell and his wounded sailors was ending.

Tributes Pour in for Dr. Wassell

Wassell took the men ashore and got them settled into a hospital. A few days later, he was summoned by an American admiral and informed that he had been awarded the Navy Cross for his “gallantry and splendid leadership.” The unassuming Arkansan was stunned and wept when the admiral told him of the tribute the Marblehead sailors had paid to him.

Wassell became a national hero when his exploits were revealed in a radio broadcast by President Roosevelt on April 28, 1942. In one of his widely heard “fireside chats,” FDR announced, “… The men were suffering severely, but Doctor Wassell kept them alive by his skill and inspired them by his own courage. As the official report said, Wassell was ‘almost like a Christ-like shepherd devoted to his flock.’”

Returning to the United States, the gallant doctor served at the San Pedro navy base in California until June 1944, when he became the assistant navy public relations director for the West Coast. He was promoted to captain in July 1943. That year, his inspiring story was told in a biography by James Hilton, British author of the classic novels Goodbye, Mr. Chips and Lost Horizon. More fame was to follow, for Hollywood director-producer Cecil B. DeMille, who had heard Roosevelt’s broadcast, decided that here was a worthy subject for a major motion picture.

On a memorable night in April 1944, the former country doctor and medical missionary went to Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C., for the premiere of DeMille’s The Story of Dr. Wassell. The epic, 140-minute film starred Gary Cooper in the title role, which was one of his most sensitive performances, supported by Laraine Day, Dennis O’Keefe, Signe Hasso, Paul Kelly, and Philip Ahn.

Wassell was detached to the naval training center in Miami, Fl., until August 1946, when he retired with the rank of rear admiral. The following year, he and his wife resumed their medical missionary work, joining the staff of the Shingle Memorial Hospital, an Episcopal mission on the Hawaiian island of Molokai. The couple worked without pay. They left the hospital in December 1947, however, because the famed doctor said it “is being run as a commercial public institution and not as a missionary institution.”

After living in Florida for a time, the Wassells returned to Little Rock in 1956. The Navy Cross hero died there on May 12, 1958, at the age of 73, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Michael D. Hull is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He resides in Enfield, Conn.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments