By Glenn Barnett

Alexander of Macedon, called “the Great,” died in June of 323 BCE having conquered the mightiest empire yet seen on earth. At his birth, the Achaemenid Empire of Persia ran from the Danube River in the West to the Indus River in the east. By the time he died it was all his.

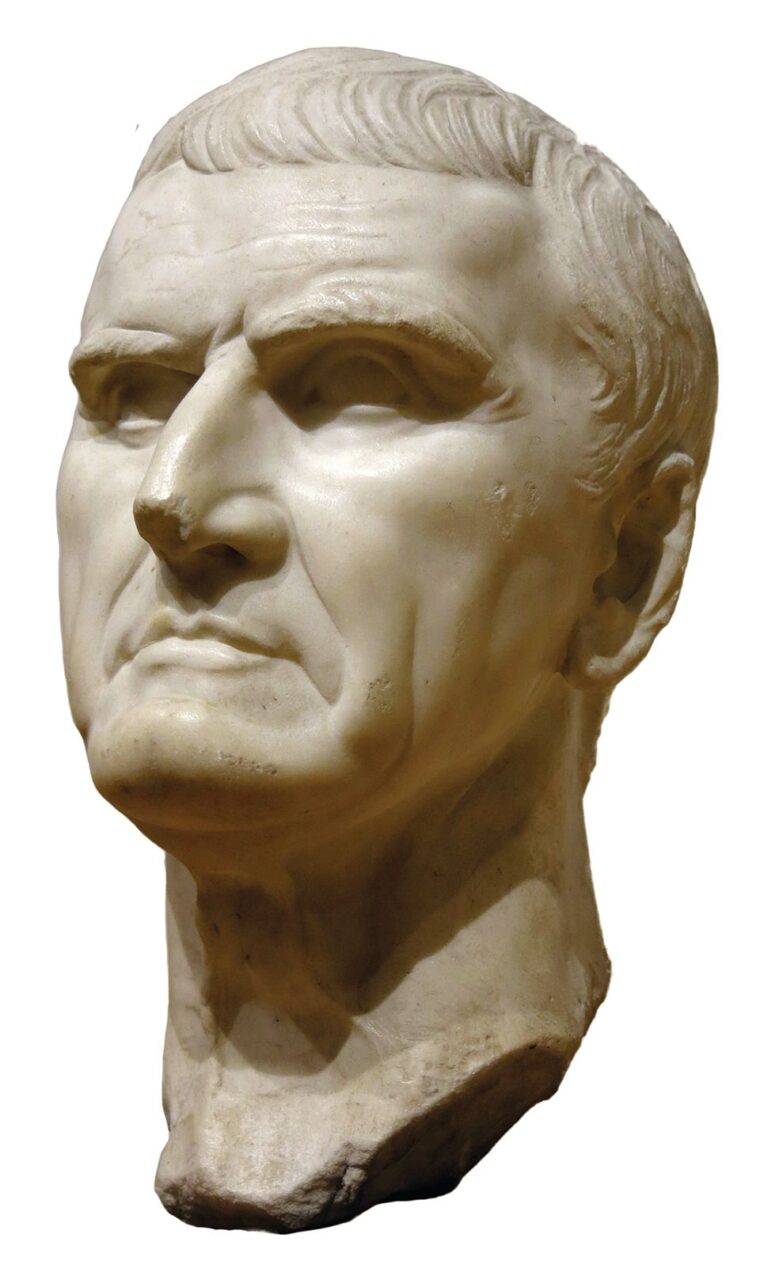

More than 250 years later, Alexander’s exploits were legendary in the growing Roman Empire and its emperors and generals idolized Alexander. In 54 BCE, the Roman general Marcus Licinius Crassus would attempt to emulate Alexander’s life and duplicate his conquests to achieve greatness.

He was not the first Roman to seek comparison to Alexander. Scipio Africanus, who defeated Hannibal and destroyed Carthage, was often likened to the Great Macedonian. So was Pompey, called “the Great” in his own lifetime. Plutarch also compared Julius Caesar to Alexander in a work that, unfortunately, has not come down to us. But Crassus was the first Roman to face a resurgent Persia with an army at his back.

Crassus’ father, Publius, was elected consul, the highest office in the Roman Republic, in 97 BCE. The following year he held the proconsul governorship (an office given to a recently serving consul) of Roman Spain. There he fought to extend Roman control over the Lusitanian peoples of today’s Portugal. It is likely that Marcus would have served alongside his father in Spain while gaining military experience.

Publius took sides in a civil war between the followers of Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla. He and his eldest son fought for Sulla and were killed by followers of Marius in 87 BCE. Alexander the Macedonian also had been the son of a powerful man who was murdered by political opponents. Marcus was now the heir to his father’s name. Fearing the same fate as his father and older brother, he fled back to Spain where he was hidden and protected by his father’s friends.

While in Spain, Crassus raised a small army of about 2,500 men to support Sulla against Marius and avenge his family. Joining Sulla for his invasion of Italy, Crassus was assigned to raise Italian troops for the Sullan cause and performed the task well enough for Sulla to give him command of the right wing of his army in what would be the climactic Battle of the Colline Gate in 82 BCE when the forces of Sulla decisively defeated the Marians.

Crassus likely delighted at being on the right because Alexander fought his two most important field battles against the Achaemenid Persian King Darius III from that position. He commanded his elite cavalry, including his household mounted unit known as “The Companions,” on the right wing of his army. In the Battle of Issus in 333 BCE, Alexander, and much of his cavalry took charge of the right flank. As the battle progressed, his left wing was in danger of collapsing.

He then led his mounted troops directly at the chariot of Darius in the center of the Persian line and forced him to flee. The sight of the king speeding away caused panic among his troops and they followed their king in great chaos.

Alexander’s next battle was on the wide plain at Gaugamela in 331 BCE, near the city of Erbil in modern Iraq, east of the Tigris. This time, Alexander moved his cavalry to the far right and Darius’ cavalry attacked him there stretching the Persian line to leave a portion undefended. On the left, the Macedonian line shifted to allow a Persian chariot charge to race through unchallenged, causing another gap in the Persian line. Alexander rushed through one opening, while troops on the left flank of his line rushed through the second gap in Darius’ line. The hard charging Macedonians once again caused Darius to flee. The Persian line and empire collapsed.

Much later, during the battle between the Marians and Sulla, the left wing of Sulla’s army collapsed and the situation was in doubt. Sulla rushed to their aid and tried to rally them, leaving Crassus in charge of the right flank. While Sulla struggled to get the troops fighting again, Crassus mimicked the charge of Alexander and maneuvered his right wing to smash into the middle of the Marian line, snatching victory from defeat for Sulla.

With his first taste of Alexandrian-like victory Crassus was rewarded by a grateful Sulla who put him in charge of taking vengeance on supporters of his enemies. In his new role he was to seize the property of aristocratic followers of the doomed cause of the Marians properties and resell them to raise money for Sulla’s veterans.

Crassus sold the property, taking a large commission or secretly keeping some of the properties. In this way he began the process that would make him the wealthiest man in Rome.

Crassus continued to increase his real estate holdings until 73 BCE, when a disgruntled Thracian gladiator named Spartacus led a slave revolt against his Roman masters. His army of escaped slaves, centered on combat proven gladiators, defeated successive Roman forces sent against him. In the process, more slaves rallied to his cause and a great number of weapons were captured for their use and turned against the Romans.

A year later, the runaway slaves were the scourge of Italy, defeating three Roman armies sent against them. Then, the victorious slaves turned south to ravage the peninsula, enrich themselves and hopefully escape to Sicily.

The consuls were defeated and humiliated while Rome’s best generals were stationed far from Italy. Pompey was in Spain putting down a rebellion while Lucius Licinius Lucullus, (a friend of Sulla) was in Thrace. A young Julius Caesar was not yet known for his fighting skills. Crassus, seizing the moment, made an extraordinary offer to the Senate. If he was given command of the Roman armies in Italy he would pay for the newly raised army from his own great wealth.

The desperate Senators accepted. Crassus immediately began recruiting, not raw recruits, but the seasoned veterans of Sulla’s army. After inheriting two legions from the now docile consuls, he soon had an army of over 40,000 battle hardened legionnaires in eight legions. They were armed, equipped and paid for by Crassus himself.

At the start of the campaign, a commander disobeyed orders and led his forces against Spartacus and was defeated. Worse, the legionnaires broke and ran. Crassus punished them as Alexander had once done—through decimation, in which every tenth man in the disgraced unit is killed by his peers. Discipline was restored.

This theory stems from Alexander’s Roman biographer Quintus Curtius Rufus, who wrote that Alexander put to death 600 out of 6,000 soldiers that had abused their authority over a subject province. Rufus lived a generation or two after Crassus and the decimation story can’t be conclusively proven—but if it were true, then Crassus would have been following the lead of his hero.

While Crassus recruited, trained and punished his newly formed army, Spartacus had reached Calabria in the toe of Italy, seeking transport to Sicily where the spirit of rebellion smoldered among slaves working the farms and mines of the island.

Spartacus offered locals money for transport to Sicily, but the ship owners feared Rome more than they did the desperate slave leader. They took his gold but never provided the boats.

While Spartacus waited in vain, Crassus brought his army in behind them. In a wonder of Roman engineering, his men and locally conscripted civilians built a trench with periodic ramparts along the entire 37-40 mile neck of Calabria and trapped the doomed slaves.

In their first encounter, Spartacus was desperate to escape the trap that Crassus had made for him. In the middle of the night, he broke through the Roman line and most of his army escaped. But internal dissention was fracturing the unity of the slaves along nationalistic lines.

About 12,000 Gauls and Germanic people had split with Spartacus and did not participate in the breakout. Crassus discovered the schism and set his larger army on the Gauls and destroyed them.

Spartacus and his main army however were still on the loose. What’s more, Crassus had persuaded the Senate to recall Pompey and his army from Spain and Lucullus and his army from Thrace to help put down the slave rebellion. But now, with victory within his grasp, Crassus realized his mistake. The two better known generals might arrive in Italy and crush Spartacus before he could. They would get the glory. He couldn’t allow that and so went at the rebels with a terrible purpose.

Spartacus meanwhile had taken up positions in mountainous ground. Crassus, in his haste, sent his vanguard straight at them before the rest of his army could arrive. They were repulsed, giving the slaves a false hope of future victories. When Crassus had brought his army up and all was ready, he charged the slave redoubt and crushed them, killing Spartacus in the process.

The slaves that escaped their Calabrian confinement were unable to bring their supply wagons, leaving the army of Spartacus, worn down by continual marching and fighting, was in a weakened position. Crassus’ victory was overwhelming.

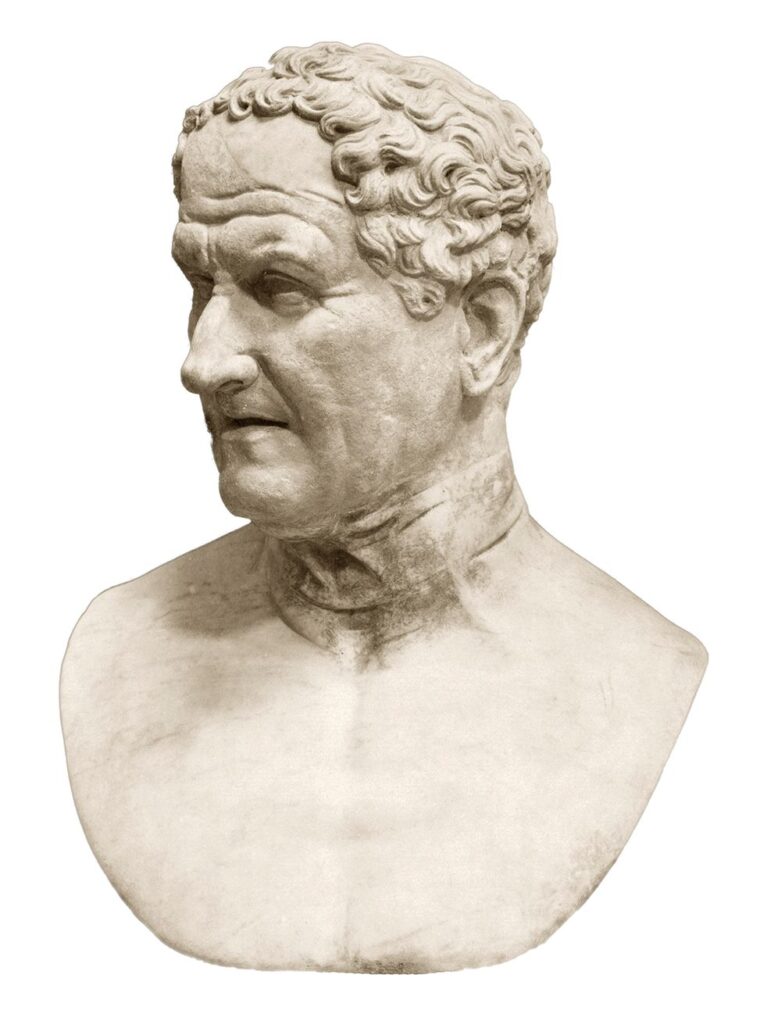

Only one event spoiled Crassus’ victory. About 5,000 slaves had escaped the slaughter on the mountain side and made a dash northward to flee Italy. They were stopped by an arriving Roman army from Spain under the command of Gnaeus Pompeius who is known to us through the anglicizing pen of Shakespeare as “Pompey.” Pompey wrote to the Senate that though Crassus had defeated the slave armies, it was he himself who had ended the rebellion.

The Senate awarded Pompey a Triumph and gave Crassus a lesser sign of victory known as an ovation. The two men then were named co-Consuls for the following year (70 BCE). Crassus and Pompey had been rivals before. Pompey’s bravado took their rivalry up a notch.

In reality, the two most powerful men in Rome had mutual interests in different spheres of influence. Pompey was the most powerful Roman general while Crassus was the wealthiest and most influential senator and politician. The men found common ground when they served as consuls.

Following their joint consulship, Crassus remained in Rome amassing his fortune and building political alliances. Pompey went to war. First, he systematically vanquished piracy from the Mediterranean and Black Seas and then assumed command of a mutinous army in Rome’s war against Mithridates VI of Pontus.

Pompey reinvigorated the new army. He now commanded Anatolia and defeated the armies of Pontus. After his defeat, Mithridates fled to Armenia where his son-in-law was king. That man, Tigranes the Great, now opposed the Romans. To aid his cause Pompey negotiated with the Parthians, who then controlled Persia, for a joint invasion of Armenia. However when the Romans were victorious, without the aid of Parthia, he canceled the deal. By that time however, Parthia had sent cavalry into the Armenian occupied territory of Gordyene (in southwestern Turkey) which had only recently been a Parthian territory before Armenia seized it.

Pompey restored Tigranes to his throne as a Roman client king and sent his legate, Aulus Gabinius, the length of Armenia to the banks of the Tigris River as a show of force. He sent another legate, Lucius Afranius, to evict the Parthians from their re-conquest of Gordyene. The small Parthian force there left without a fight.

Afranius followed up this insult to Rome’s would-be ally with another. He marched his army across the Mesopotamian plain to Antioch on the Mediterranean coast. In doing so he crossed the formerly Seleucid territory claimed by Parthia since 141 BCE. Significantly he passed through the town of Carrhae on his westward march. As a final insult, Pompey annexed Parthian-claimed Pontus and Syria to the growing Roman Empire.

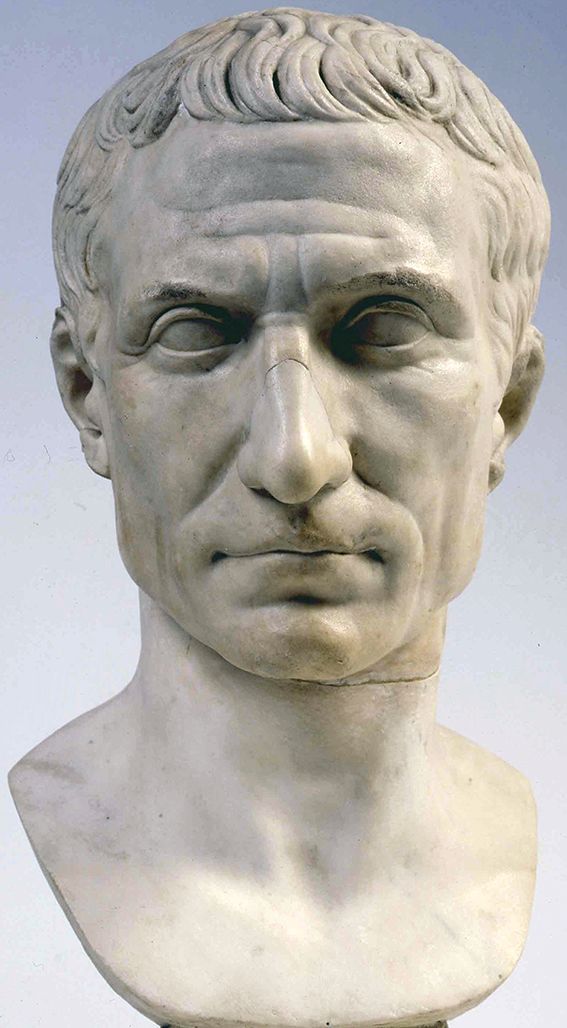

As Pompey fought in the east, Crassus made money financing up-and-coming politicians of both the aristocratic and equestrian classes. The most famous of these was a young Julius Caesar to whom he loaned a good deal of money and supported his early political and military career.

When Pompey returned to Rome under a cloud of suspicion from the Senate for stepping outside the bounds of the mandate he had been given, Crassus backed his rival. Their uneasy alliance would culminate in their mutual support of Julius Caesar to be consul in 59 BCE. Caesar shrewdly balanced his financial obligation to Crassus by arranging a marriage between his daughter Julia and Pompey, securing his ties to both men. Soon Crassus would secure another link to Caesar by sending his son Publius to serve in Caesar’s army as a cavalry captain.

As consul, Caesar adroitly arranged for measures benefiting both his patrons to be passed by the Senate. As his reward, Caesar was given the proconsul governorship of Cisalpine Gaul, which at that time consisted of northern Italy. Caesar would use that base to build his own personal fiefdom. He would use Transalpine Gaul (France) as a springboard to eclipse his mentors.

With Caesar away from the capital, two conflicting gangs controlled by Pompey and Crassus fought each other in the streets of Rome. The people divided their political loyalties between the two men. By 55 BCE, with Caesar’s blessing and support, the two giants reconciled and were once again elected joint consuls as they had been in 70 BCE.

During this consulship, the proconsul governor of Syria, Pompey’s man Gabinius, was in Judea to stop a civil war when he received a petition from a man named Mithradates, the brother of the Parthian king Orodes II, requesting his support in the struggle for the Parthian throne. Gabinius agreed and got his army across the Euphrates River before being recalled by Pompey to restore the deposed King Ptolemy XII Auletes (the father of Cleopatra) to the Egyptian throne. Among Gabinius’ soldiers at this time was a young cavalry captain named Marcus Antonius, who Shakespeare would rename, Mark Antony.

Back in Rome, an uneasy alliance between three men, Crassus, Pompey and Caesar, informally controlled Roman politics from 60 to 53 BCE. This alliance is known to historians as the First Triumvir. When they divided up the pie, Caesar was given another five years to subdue the vast territory of Gaul. Pompey was given the governorship of Spain and Crassus was given the governorship of Syria and allocated seven legions–.

Crassus craved military greatness like that achieved by Pompey and Caesar. He had won only one battle under Sulla’s command and Pompey had won the praise for Crassus’ victory over the slaves. He wanted victories of his own without interference from his rivals and peers.

Plutarch, writing over a century later, recorded that Crassus was, “altogether exalted and out of his senses, he would not consider Syria nor even Parthia as the boundaries of his success, but… flew on the wings of his hopes as far as Bactria and India and the Outer Sea.” In other words, he sought to emulate the great Alexander.

He arrived in Syria in 55 BCE and relieved his predecessor Gabinius. Crassus was in a strong position as he, like Gabinius, backed the Parthian pretender Mithradates, who was now in a strong position as he held the wealthy cities of Babylonia under Parthian control. In addition, the king of Armenia sought to align his country with Rome and offered up to 40,000 Armenian infantry and cavalry for the allied effort against the Persian enemy. Local Arab tribal leaders also offered to support Crassus.

In addition to these advantages, Crassus could reflect that he had considerably less work to do than Alexander had done to accomplish his dreams of empire. The Macedonian had to fight his way across Asia Minor, Syria, Judea and Egypt before crossing the Euphrates River to get at Darius and his army. By Crassus’ time all those territories were either Roman provinces or client kingdoms. The Alexandrian battlefields of Granicus and Issus were already under Roman control and Crassus could begin his campaign from the banks of the Euphrates River.

Crassus quickly crossed the river and marched on local towns, finding local Parthian forces easily dealt with and dispersed. There was little opposition from most of these Greek inhabited towns, save one. With the campaign season nearly over, Crassus left a garrison on the east bank of the river and returned to Syria for the winter.

Crassus spent that winter governing his province, training his soldiers and raising funds for the coming showdown with the Parthians. It was the custom for ancient armies to split up during winter to several different garrisons. This was done to prevent the hardship that would be felt by a single city if it had to feed and house an entire army.

It was also in keeping with the norms of ancient armies to collect taxes from allied or conquered territories before beginning a new campaign. According to Arrian who did his writing between 146 and160 AD, when Alexander returned from Egypt to Syria he set a “levy of tribute in Phoenicia (western Syria)” and other kingdoms. Crassus now did the same. His grasp reached as far as the Temple of Jerusalem which was also forced to contribute. The Jews would view his coming disaster and untimely death as God’s just punishment for his confiscation of Temple funds.

Crassus also had to choose the route of his invasion. The first route, once used by 10,000 Greek mercenaries in 400 BCE, as recorded by Xenophon, led down the Euphrates river valley to the wealthy cities of Seleucia and Babylon (near today’s Baghdad). This would allow him to meet up with his Parthian ally Mithridates III, who anxiously awaited his arrival.

Whichever route was taken, the rich, Greek-populated city of Seleucia was the Roman goal, as Crassus informed a Parthian negotiator named Vagises. It is said that when informed of Crassus’ intentions, Vagises pointed to the palm of his hand and said to him, “Hair will grow here before you reach Seleucia.” His words were prophetic.

Yet that winter, while Crassus rested, the strategic situation changed. The Parthian king Orodes sent a force against his brother Mithradates. This army was led by a nobleman we know by his clan name, Surena. He defeated the Parthian pretender and sent him in chains to his brother Orodes for execution. Crassus, deprived of a valuable local ally, had no more reason to take the first route to confront his enemy.

The second route that Crassus could take would be through the mountains of Armenia to Media on the southern shores of the Caspian Sea. In 209 BCE, the powerful Seleucid King Antiochus the Great had used this route to temporarily defeat the growing power of the Parthians.

Crassus was urged by Artavasdes, the Roman client king of Armenia, to use this route while repeating the offer of 40,000 soldiers for the joint effort. But Crassus had his doubts about the loyalty of this ally whose father had once been the client king of Parthia and who, when summoned with his army to Syria, was very late in arriving and even then with only 6,000 cavalry. Crassus snubbed the invitation to march through Armenia to get at the Parthians. Insulted, Artavasdes took his army and returned to his own country to await the outcome and embrace the victor. It was another change in the strategic situation. Crassus did not heed the warning signs.

The third route that the Romans could take in 53 BCE was through the Mesopotamian plateau. The ancient sources tell us of an Arab chieftain named Ariamnes (by Plutarch) or Abgarus (by Dio) who advised Crassus to take this route rather than march southward along the Euphrates to Babylonia. Plutarch suggests that Crassus was easily swayed by this argument. But the Roman general had long ago decided to go this way.

It was the route that Alexander the Great had used in his invasion of Persia. He, like Crassus, wanted to head straight toward the enemy and destroy his army before occupying the rich cities between the rivers. When Alexander defeated Darius III at Gaugamela, the cities of Babylonia fell to him like ripe fruit. Crassus could expect the same outcome when he, too, was victorious against the Persian army.

As we know from Alexander’s experience, he would ultimately want to occupy Seleucia and the rest of Babylonia to tax its wealth. When he received the Parthian ambassador Vagises who asked him his intentions, Crassus, not giving away which route he would take, replied that he would give him an answer in Seleucia.

According to Plutarch and others, Crassus would have seven legions (approx. 35,000 infantry) under his command as well as 4,000 auxiliary infantry and 4,000 cavalry. The estimates given by ancient sources for Alexander’s army are roughly the same number of men when he began his invasion of Persia.

Arrian, a biographer of Alexander, says the Macedonian and his army crossed the Euphrates River at the town of Thapsacus. The precise location or name of this town today isn’t known. In the early part of the third Century CE, Cassius Dio writing between 165 and 235 CE, wrote that Crassus crossed the river where Alexander had. Historians continue to debate this, but Dio at least, saw Crassus consciously pursuing the course of Alexander’s invasion.

Across the river, Alexander was confronted by a Persian Satrap named Mazaeus who commanded 3,000 horsemen. Mazaeus fled the oncoming Macedonians. Crassus had a similar experience. Plutarch wrote that, “Some of his scouts now came back from their explorations, and reported that…they had come upon the tracks of many horses which had wheeled about and fled from pursuit.” He goes on to say that when Crassus heard of it he became more confident of victory. He pushed on in the path of Alexander. Everything was playing out for Crassus just as it had for Alexander.

An Arab chieftain named Ariamnes, who had once sided with Pompey, arrived at the Roman camp and was remembered by some of the veterans. Plutarch has the man telling a gullible Crassus that he should rush forward to meet the forces of the Persian king before they could form defensive lines on the Tigris River against him. Plutarch faults him for this. But in all likelihood, this is what Crassus had in mind anyway.

Alexander, fearing that Darius III might fortify the Tigris River against him, had rushed his army forward to prevent it. Crassus did not need persuading to do the same, seeing it as more evidence he was following in Alexander’s footsteps.

It should be noted that, for their part, the Parthians had conquered and inherited the bulk of the Seleucid Empire. The Seleucids revered their founder, Alexander. The Parthians, the new masters of Persia, would have known of the Macedonians’ exploits against Darius III, and took advantage.

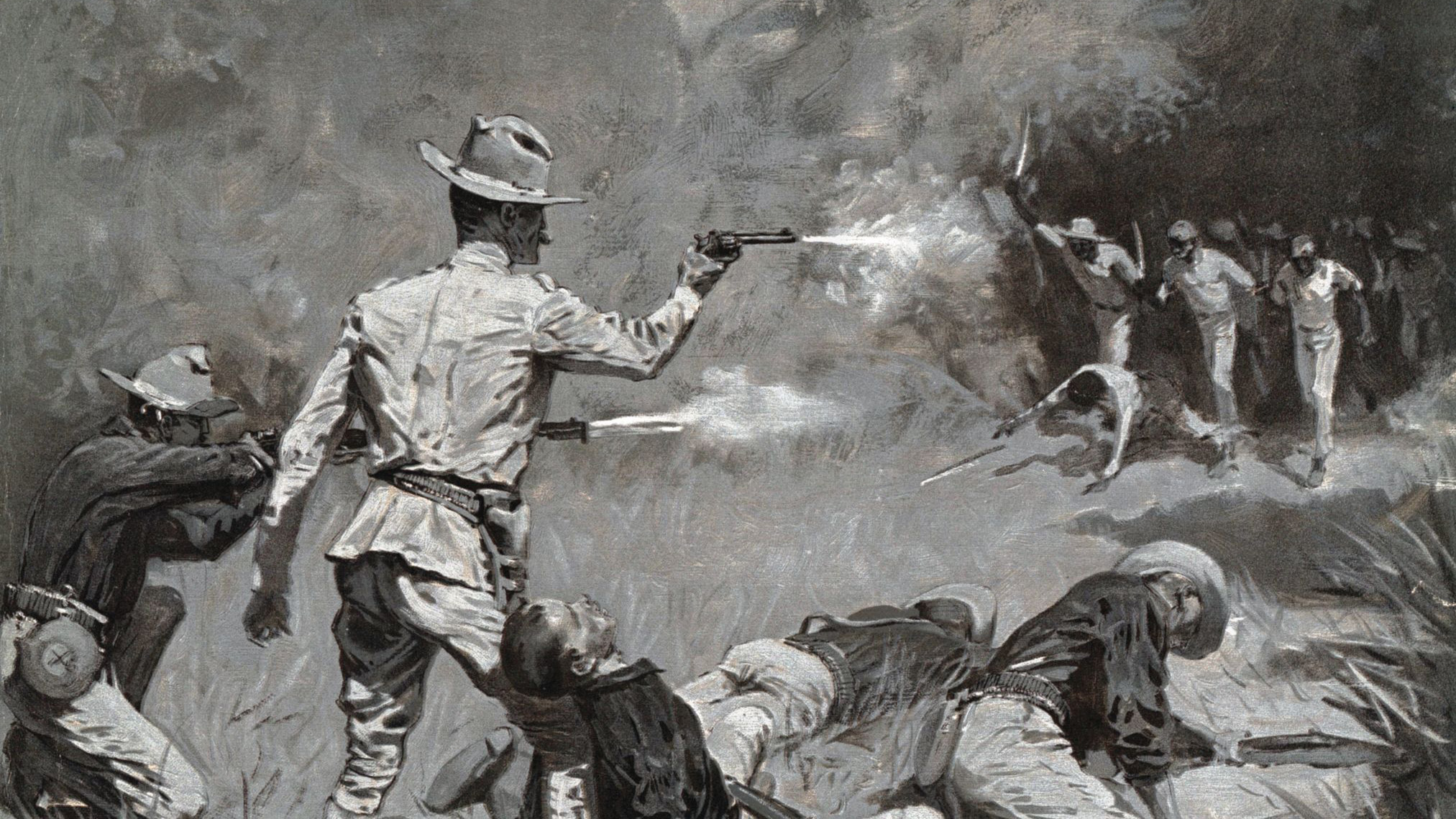

Rather than retreating behind the Tigris River as Darius had done, they let Crassus advance to a remote spot, favorable for cavalry, and unleashed a mounted attack from all sides. Just before this happened, the Arab tribal leader Ariamnes, having performed his part in the Parthian play, led his men hastily out of the Roman camp.

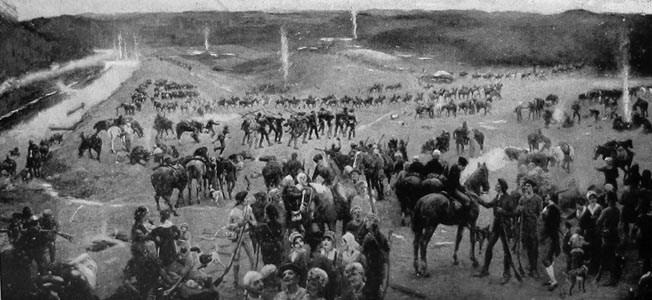

Surrounded by cavalry, the Romans formed a hollow square with shields, bristling swords and spears—a sound tactic against infantry, but not mounted Parthian archers, whose arrows pierced Roman shields and bodies from a distance.

The Parthians confounded Roman expectations that they would exhaust their quivers, then attack their impregnable square. Instead, the Parthians retreated to refill their quivers from a camel caravan of supplies, then returned to the attack, wounding and killing more legionaries. It is one of the few accounts of a coordinated logistics plan among ancient non-European armies.

When Crassus sent out his own cavalry commanded by his son Publius, who Caesar had sent to him from Gaul as a token of his support, the Parthians fled, leading them into a trap of heavy cavalry known as cataphracts— horses and riders covered in armor the likes of which the Romans and their Gallic cavalry had never seen. The end was swift and Publius’ severed head was thrown into the Roman square as his father despaired.

Crassus retreated that night—when the Parthians did not like to fight—to escape to the town of Carrhae. News of the Roman defeat had preceded the haggard soldiers of Rome and the fearful city would not open its gates to the losing side.

The next morning, the Parthians followed, killing the Roman wounded. When Crassus tried to negotiate with Surena, he was also killed.

Some of the infantry survived to reach the safety of the west bank of the Euphrates River by forced marches at night and hiding during the day. Many of the remaining Roman cavalrymen also escaped. They were led by an officer named Gaius Cassius Longinus who would later be one of the assassins of Julius Caesar.

For Crassus, his name would live in infamy for as long as Roman or Byzantine historians wrote the history of their country.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments