By Victor Kamenir

The year 1943 began badly for the German Army on the Eastern Front. After a great struggle at Stalingrad, German Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus surrendered himself and his Sixth Army on January 31. Powerful sledgehammer blows from the strengthening Red Army began to shudder the entire southern flank of the German Army.

In the Caucasus, the Soviet steamroller started clearing the Taman Peninsula to eliminate the German threat to the Caspian Sea oil fields. The key to securing the entire northeastern shore of the Black Sea was Novorossiysk, an important deep-sea port city held by the Germans since September 1942.

The goal of Soviet Operation Sea was to cut off and destroy German and Romanian forces operating in and near Novorossiysk. The German 17th Army defending this area was composed of both German and Romanian divisions. The Soviet 47th Army, from the North Caucasus Front under General I.E. Petrov, was to launch an overland assault from northeast of the city. Once the troops of the 47th Army breached the German defenses, the Soviet 18th Army, also from the North Caucasus Front, was to land its forces in the immediate vicinity of the city itself, on the Tsemess Bay.

With the German occupation of Sevastopol and Novorossiysk in 1942, the Soviet Black Sea Fleet had lost its primary naval bases. Its operations were shifted farther down the southeast coast to the city of Poti, whose port facilities were small and poorly equipped to serve as a naval base. An even smaller port, Gelendzhik, closer to Novorossiysk, picked up part of the workload. The recapture of Novorossiysk would provide the Soviet Black Sea Fleet with a base large enough to accommodate its naval forces.

The Soviet 47th Army launched its attacks northeast of the city on February 1, 1943. The spearhead was unable to breach German defensive lines and reach its objectives. To support the 47th, Petrov ordered the 18th Army to land its forces from the sea no later than February 4.

This amphibious assault was to be carried out in two locations. The main landing force was to come ashore in the vicinity of the village of South Ozereika. This force was composed of the 255th Naval Infantry Brigade, the 563rd Separate Tank Battalion, and supporting assets. South Ozereika is located southeast of Novorossiysk, and a Soviet force landed there would be a direct threat to German rear echelons.

A diversionary landing was to take place on Cape Khako on the western side of the Tsemess Bay, near Stanichka village, which was situated in the vicinity of Novorossiysk. The 250 men in this battalion task force came from the 255th Naval Infantry Brigade. The Black Sea Fleet, under Vice Admiral F.S. Oktyabrsky, was to transport the troops and provide covering bombardment. Oktyabrsky was in the overall command of the operation.

The armored fist of the primary assault, the 563rd Separate Tank Battalion, was formed in the summer of 1942. Initially, the battalion was equipped with British Valentine and American Stuart Lend-Lease tanks, but eventually became entirely equipped with M3A3 Stuarts.

The lack of appropriate landing craft was to play a key, and tragic, role in the operation. Instead of actual amphibious assault craft, the Soviets were forced to use bolinders, which were shallow-draft, self-propelled barges. These craft were named for a Swedish firm that had produced maritime commercial vessels in Russia before the 1917 revolution. At this time, three bolinders were in use by the Black Sea Fleet, but they could no longer move under their own power and were used as towed barges or temporary floating docks. These were the only tank-landing resources available for Operation Sea.

The plan called for 30 tanks to land in the first echelon at South Ozereika. After disembarking the tanks, the bolinders were to revert to their role as floating docks and receive troops disembarking from gunboats, trawlers, and transports, which could not get close to the beach due to their deeper draft.

The Soviet command realized that the success of the whole operation depended on the ability of these three ancient, dilapidated craft to get close to land. To ensure their survival, Soviet aviation and naval supporting bombardment were to provide cover for the landing. Small groups of minor combat vessels were to draw attention away from the landing group.

Embarkation began in the evening of February 3 in Gelendzhik, which was ill equipped to handle an operation of this size. The units participating in the operation did not have an opportunity to practice embarkation and quickly fell behind schedule. Miraculously, at 1940 hours, only 30 minutes late, the first echelon of the landing force began to get underway. The sea conditions were not taken into account in planning, and minor swells further slowed the tempo of the operation.

It immediately became apparent that the bolinders, heavily loaded with tanks, were creeping along at a much slower speed than was planned. Bolinders, even in their prime, were designed for in-shore work and they were completely inadequate to cross the open waters of the Tsemess Bay. The timetable began to fall further and further back. It was soon determined that the ground assault force was going to be one and a half hours behind schedule.

This meant that the assault troops would hit the beach well after the scheduled air and naval strikes and diversionary landing took place. Realizing that this meant the failure of the whole operation, the first wave commander, Captain 1st Rank (Captain) N.E. Basisty, requested that the operation commander, Vice Admiral Oktyabrsky, delay the diversionary landings and fire support by 90 minutes. Extreme inflexibility in decision-making and the strictest adherence to plans had plagued the upper echelons of the Soviet command throughout the war, so it is of little surprise that Oktyabrsky denied the request.

Heavy naval bombardment and air strikes began at 0045 and lasted over two hours. For the first time in naval warfare, several vessels had “Katyusha” multiple rocket launchers mounted on them. The naval bombardment was largely ineffective due to a lack of fire correction. It did succeed, however, in alerting the German and Romanian defenses.

In the weeks preceding the operation, numerous reconnaissance parties had landed on the beach. They had been spotted by the Germans and Romanians and the defenders were prepared for a possible amphibious landing.

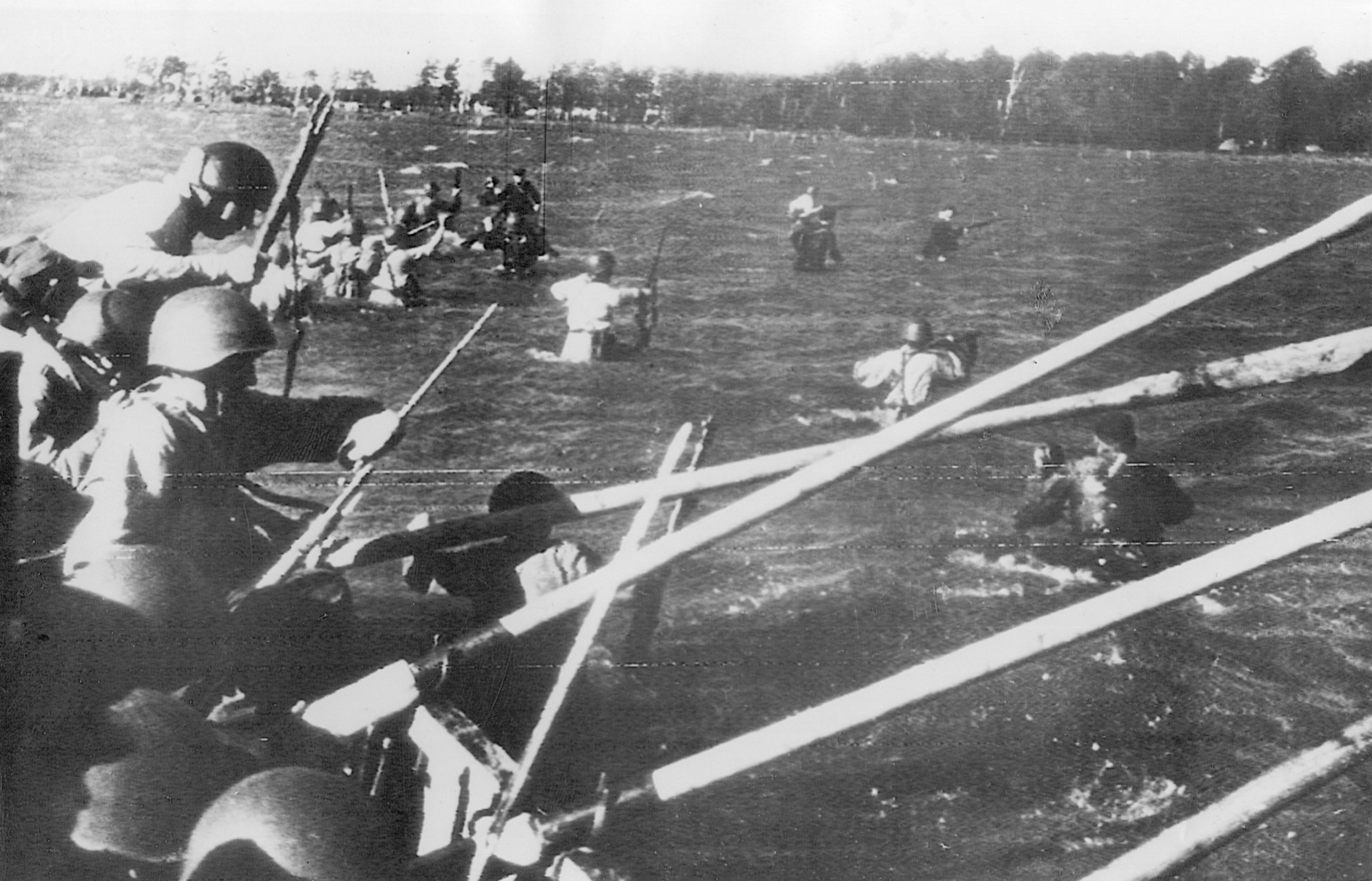

At 0335 on February 4, six cutters packed with 300 naval infantrymen darted toward the Axis-occupied shore. The defenses came alive. The bulk of the defenders on this stretch of the shoreline were from the Romanian 10th Infantry Division. The Germans were represented in small but effective numbers of specialist troops, mainly field and antiaircraft artillery batteries and searchlight crews. Well-manned searchlights reached out and found the advancing Soviet craft, which immediately came under heavy artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire.

Two cutters were hit right away and one of them, SKA-051, exploded. The resulting losses cut the assault force by a third, with only 200 out of 300 men actually landing. The loss of SKA-051 was doubly significant because the commander of this spearhead force, Captain 3rd Rank (Lieutenant Commander) A.P. Ivanov, was killed, leaving the troops without effective command and control.

Since Ivanov was dead, there was no one to give the bolinders the signal to advance closer to the shore. Roughly half an hour after the landing began, the surviving naval infantrymen still were not able to suppress the German and Romanian fire. Their foothold on the beach was very tenuous. It is unknown who gave the bolinders the command to move in, but they began to creep forward. These vulnerable landing craft loaded with tanks represented a gunner’s dream: slow, fat targets. The German searchlights easily spotted the approaching bolinders.

Immediately, the bolinders came under fire. The very first hits on Bolinder No. 2 and its tugboat Gelendzhik caused serious damage and set the vessels on fire. Still over 200 meters away from the shore, both vessels began to sink. The 350 men on board—naval infantrymen and tank and vessel crews—were forced to jump into the freezing water and swim ashore under fire. All 10 tanks on board, a third of the total armored force, were lost.

The two remaining bolinders and their tugs continued to doggedly move toward the shore. A hundred meters from the shore, another bolinder ran aground on an underwater steel hedgehog obstacle. The barge began to rapidly settle to the bottom. Luckily, the tanks were able to begin disembarking due to the shallow depth at this location.

The immobile bolinder became a fixed target for Romanian mortars and was soon set ablaze. Despite desperate and heroic attempts by the crew to put out the fire, it spread rapidly. Soon the flames reached ammunition stored aboard and the bolinder exploded. Still, seven of the 10 tanks aboard were able to disembark and reach the shore. They immediately entered the fierce fight raging on land. The fight in the dark was at close quarters and often hand-to-hand.

The German searchlights, overhead flares, and the fires aboard the burning ships illuminated ample targets for the defenders, but the appearance of Soviet tanks on shore demoralized the Romanian soldiers.

At this time, a third bolinder, which had fallen behind on the approach, began its run at the shore. Both the bolinder and its tow-ship, the cutter SP-19, were hit. The tow cable was severed, and the barge began to turn and drift. Despite a fire raging aboard, the crew was able to maneuver the bolinder close to the shore, and some of the tanks began to unload. Others were engulfed by the flames.

The destruction of the bolinders and continuing fire from shore severely impeded the ability of the follow-up echelons to disembark their landing parties from the gunboats and trawlers. Several vessels kept trying to approach the shore until 0600, but each time they were met with a barrage of fire and were forced away with heavy loss of life. Only one battalion from the 255th Naval Infantry Brigade and some elements from the other two were able to land.

At 0620, fearing possible German air strikes, Basisty ordered the remaining ships to turn back to Gelendzhik. At this time, there were approximately a thousand men fighting on the beachhead. They were the survivors of the 563rd Separate Tank Battalion, elements of three battalions of the 255th Naval Infantry Brigade, and crews from sunken vessels. They did not have a single working radio among them. The brigade commander, Colonel A.S. Potapov, and his headquarters staff never had an opportunity to disembark.

Another significant flaw in Soviet planning then came to light. Despite numerous reconnaissance attempts of this area, the scouting parties failed to report that this section of the beach did not allow tanks any room to maneuver. The Stuarts were channeled onto a narrow rocky road covered by defensive positions. A number of Romanian mortars were deployed on the reverse slopes of nearby hills and were firing on presighted points on the shore.

While engaged in constant and confused fighting, the surviving Soviet officers began to slowly organize their men around them. At this time, the highest ranking officer on the beach was a Captain Kuzmin, commander of 142nd Naval Infantry Battalion. It is probable that he assumed command and began to coordinate actions with the surviving tanks to liquidate Romanian strongpoints. Crews from destroyed tanks picked up whatever weapons they could and joined the infantrymen.

Soon, the Soviet fighters found a weak spot in the Romanian defenses. The banks of the Ozereika River, flowing through a deep ravine, were not defended. A large group of naval infantrymen infiltrated around the Romanian right flank and hit them from the rear, in the direction of the village of South Ozereika.

Fearing all was lost, the commander of the German 164th Air Defense Battery blew up his two guns and retreated. Following his lead, Romanian infantrymen from the 53rd Infantry Regiment, 10th Infantry Division abandoned their positions en masse, leaving behind over 300 men killed, wounded, and taken prisoner. Russian casualties were heavy as well, with no more than 800 men and eight tanks still combat capable.

The survivors of the assault force had three bleak choices. The first was to defend their position on the shore and hope for a rescue. The second was to try to fight their way south to where they knew a diversionary landing was taking place. The third was to continue their mission and proceed to their secondary objective, the village of Glebovka. Without alternative orders and out of communication with higher command, the landing force continued its push inland.

There were not sufficient German or Romanian troops in the immediate area to effectively stop this force, but they did put up a stiff resistance. Three out of eight Stuart tanks were destroyed by noon on the narrow road from South Ozereika to Glebovka. By the evening of February 4, the naval infantrymen reached Glebovka and captured its southern outskirts.

By this time, the Germans were able to concentrate one mountain infantry and one tank battalion and four artillery and two antiaircraft batteries against the advancing Soviets. Romanian units were reformed and reoccupied their abandoned positions on the shore, effectively cutting off the Soviet landing force from possible extraction.

Two Soviet cutters were sent out from Gelendzhik after nightfall to reestablish communications with the troops stranded on the beach. After coming under fire from the Romanian forces, the ships returned to their base without any solid news. Throughout the next day, Soviet reconnaissance aviation reported that there was still fighting in the area. Vice Admiral Oktyabrsky decided not to land reinforcements or resupply and support the survivors by air. Instead, all available resources were shifted to the second landing site at Cape Khako, farther to the southeast. The men of the 255th and 563rd were now doomed.

Ammunition was running out and casualties were continually mounting. The remaining two tanks, out of cannon ammunition, were forced to use only their machine guns. In the last desperate stand to defend dugouts full of wounded, both tanks were hit and destroyed. By the end of the day, only about a hundred men were still able to fight.

That night, the remainder of the landing force split up. Captain Kuzmin and 75 men attempted to fight their way to Cape Khako, while the remaining 25 set off in the direction of Abrau, toward the coast. The latter were lucky; they made contact with partisans who had communications with the Soviet command and were soon evacuated by cutters. Twenty-two days after the landing, five men from the larger group made it to the Cape Khako beachhead. Neither Captain Kuzmin nor a single tank crewman were among them.

The events at Cape Khako unfolded quite differently. A diversionary force of 250 men landed on schedule in the vicinity of the small fishing village of Stanichka. Their purpose was to draw attention to themselves and away from the main landing at South Ozereika. Unofficially called smertniki (destined for death), they knew that there was little chance of their survival. Armed only with light infantry weapons, the men, led by Major Cesar L. Kunikov, were all volunteers from the 255th Naval Infantry Brigade. Cesar Kunikov was an experienced and capable officer, distinguished in prior actions on the Azov and Black Seas during 1941 and 1942. His men held him in the highest esteem. Legend has it that when Kunikov called for volunteers for his task force, he announced: “Who wants to go die with me?” More men than were needed stepped forward.

The attack was launched under cover of naval bombardment and air strikes. Several cutters lay down a smoke screen. As at South Ozereika, Katyusha rockets mounted on trawlers added their firepower to the effort. Several torpedo boats fired directly at port facilities and the quay. Even though they achieved surprise, Kunikov’s men encountered heavy resistance from the very beginning. Fighting in the dark was in extremely close quarters, often hand-to-hand. Twice slightly wounded, Kunikov continued to lead his men from the front.

Soon, Kunikov was able to report by radio that a tiny strip of rocky shore was secure. Within hours, reinforcements diverted from South Ozereika were landed, bringing his force to approximately 800 men. Without allowing the Germans time to regroup, Kunikov launched an assault that resulted in the capture of a German artillery battery. This attack also succeeded in occupying several streets on the southern edge of Stanichka. The beachhead was now expanded to an area four kilometers wide and two-and-a-half kilometers deep.

During the next three days, desperate for some success after the failure of the landing at South Ozereika, the Soviet command poured in reinforcements.

Kunikov’s depleted force was pulled back to the water and tasked with organizing operations on the makeshift wharf: meeting and directing arriving reinforcements, weapons, and supplies, as well as evacuating wounded. On the night of February 12, Major Kunikov stepped on one of the German mines that still littered the beachhead and was seriously wounded in the groin. Had qualified medical help been readily available, he might have been saved, but by the time he was evacuated two days later, gangrene had set in. Kunikov died on February 14, shortly after arriving at Gelendzhik Hospital. He was posthumously made a Hero of the Soviet Union, the highest Soviet military recognition.

The overall command on the beach first passed to the commander of the 255th Naval Infantry Brigade, Colonel A.S. Potapov, fresh from the disaster at South Ozereika. Soviet forces on the beach rapidly expanded to a task force comprising the 255th and 83rd Naval Infantry Brigades as well as the 165th Infantry Brigade. Within days, General D.V. Gordeyev took over command of this task force from Potapov. He aggressively expanded operations, and by February 10 had captured the whole of Stanichka village and the 14 southernmost city blocks of Novorossiysk. The beachhead now extended to a 34-kilometer wide and seven- kilometer deep perimeter.

Despite desperate German efforts to liquidate the beachhead, Soviet forces continued to gain momentum. A total of four infantry brigades from the 16th Infantry Corps of the 18th Army and five partisan detachments were now operating south of Novorossiysk. By February 15, Soviet forces on the beachhead numbered over 17,000 men, 95 artillery and mortar pieces, and 850 machine guns. The strip of land captured by Kunikov’s men became known as “the little land.”

Heavy fighting continued. The area occupied by the Soviet forces was fully visible to the Germans deployed on the heights above the bay, so resupply and reinforcement could be carried out only at night. German air strikes and artillery fire were almost constant. Soviet reinforcements heading for the shore were attacked by German aircraft and long-range artillery while still on the water. Their naval vessels had to run the gauntlet of not only artillery and aircraft fire, but also mines dropped from German aircraft.

The lumber needed to construct bunkers and trenches was cut several kilometers from Gelendzhik, then tied onto rafts and towed to the beachhead behind navy cutters under the cover of darkness. Once under German attack, the rafts could neither maneuver nor get away from the fire. Their only option was to slowly plod on toward the shore. If a raft took a hit, the timbers would be pulled together as much as possible in order not to lose the precious cargo. If a towing cutter was hit, the crew would give a prearranged signal with rockets and wait in the water for rescue.

Vicious air combat was raging above the beachhead as well, with the Soviets slowly gaining air superiority. In some areas on the beachhead, the opposing trench lines were within a grenade’s throw of each other. The Soviet soldiers would often line their front trenches with their white undershirts to make sure their own aircraft delivered their payloads to the right address. Soviet pilots shot down over Tsemess Bay who landed in the water would usually drown because they were not issued safety vests.

At night, combat engineers on both sides, either repairing or destroying defenses, often engaged in brutal hand-to-hand fighting. Even the term “night” was relative, due to the large number of flares and searchlights deployed by German forces.

After the war, future Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev wrote a book called Malaya Zemlya (The Little Land). In it, he claimed to have been in the thick of the fighting on the beachhead. At the time, he was a commissar with the rank of colonel attached to the headquarters of the 18th Army. There were multiple and persistent rumors that his claims were wholly made up and the closest he got to the action was to tour the battlefield after Novorossiysk was liberated.

For a little over seven months, the Stanichka/ Cape Khako beachhead was a bleeding ulcer for the German 17th Army. The Germans

continued to commit men and machines in attacks to liquidate the beachhead, pulling them away from other sectors of the front. On September 10, 1943, the Soviet forces of the North Caucasus Front launched their final attack on Novorossiysk. The three-pronged assault, from the north and east overland from the Stanichka/Cape Khako beachhead, along with another seaborne landing from Gelendzhik, was successful. On September 16, 1943, the city of Novorossiysk was once again in Soviet hands.

The price the Red Army paid for the liberation of the city was high, with 21,000 men killed on the Cape Khako beachhead alone. According to German sources, the Soviet casualties at South Ozereika amounted to 630 killed and 542 taken prisoner. Roughly 200 were presumed drowned during the landing. After the war, the landing at South Ozereika was supposedly taught at the Soviet military academies as an example of how not to conduct amphibious landings.

The rigidity of thinking coupled with inadequate and faulty planning on the part of Soviet commanders was nothing new. This circumstance plagued the Soviet military for much of World War II. A significant variable introduced into this equation for disaster was a lack of appropriate assets for an amphibious operation. The entire undertaking was staked on the performance of three inadequate landing craft.

The Soviet Union was far behind the United States in developing equipment and doctrine for amphibious operations. As usual, the Soviet rank and file, along with their junior commanders, picked up the tab, paying the bill with their blood.

Victor Kamenir was born in Zhitomir, Ukraine. He is a veteran of the U.S. Army and writes from his home in Sherwood, Oregon.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments