By Bill Warnock

Three German soldiers crept through the snow. They had infiltrated the American front line during a counterattack. Major William F. Hancock spotted the trio. The lead man towered over the others. “He must have been six foot four and weighed about 250 or 275 pounds,” Hancock recalled. The huge German clutched a Panzerfaust, which had a warhead the size of a hornet’s nest.

The major shouted to 1st Lt. Roy E. Allen, who stood nearby. The lieutenant leveled his carbine and began shooting at the Panzerfaust man. Allen’s bullets struck the soldier, and he fell after several hits. The man tried to stand up but collapsed. He remained alive and somehow managed to drag himself forward, still grasping the Panzerfaust. Allen kept shooting. The German struggled onward until he finally keeled over and lay motionless. The other two infiltrators raised their hands.

The courage of the hulking German impressed Hancock. “He was one of the bravest fellows I have ever seen. He just wouldn’t stop.” The Americans examined his body and discovered he was still breathing. “We took him to our aid station because I thought he deserved a chance to live even though he was our enemy.”

The Panzerfaust man was just one of many German casualties suffered during a series of failed counterattacks. These abortive assaults withered under the guns of the 1st Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment, part of the 2nd Infantry Division. The action took place at Wahlerscheid crossroads, and the date was December 16, 1944.

The crossroads lay several hundred yards inside Germany and within an enormous spruce forest. GIs of the 9th Infantry had seized Wahlerscheid after three days of fighting. Soldiers from the 2nd Battalion were the first ones to pierce the German defenses and, along with 3rd Battalion troops, had captured a string of enemy trenches and concrete bunkers. The 1st Battalion had also captured several bunkers and then had fought to repel the counterattacks.

On the American side, the butcher’s bill included 47 dead and scores more wounded. The weather inflicted even more casualties. During the day it warmed enough for the snow to begin melting. Clothing, webbed gear, and leather boots became soaked. At night, the mercury fell, and everything froze.

Major Hancock served as the 1st Battalion executive officer, and he never forgot the frigid temperatures. “One time my boot strings came untied and were frozen. When I attempted to retie them, they snapped like twigs. After that I learned to rub my shoestrings with my hands to warm them up.” All night long, soldiers seemed to shiver constantly. “There were times you would shake so long that you were embarrassed because you looked like you were scared to death.”

A few lucky soldiers lived inside captured bunkers, some of which had stoves with tin chimneys. Most men lived outdoors in foxholes and slit trenches. The nearness of the enemy precluded the making of fires for warmth. The men huddled together in their holes. Nobody had blankets or sleeping bags. An epidemic of frozen feet thinned the ranks. “We lost a lot of people who went back to the rear because of cold-weather injuries,” Hancock recalled. “I think we must have lost 20 percent of our command from the cold alone.”

After three days of grinding misery, the fighting strength of the 1st Battalion had dwindled to 22 officers and 387 enlisted men. When the Wahlerscheid operation began, there had been 35 officers and 678 enlisted men. The chain of command had suffered, too. Company A had lost one commander, and Company B had also lost one. The men of Company C had lost two commanders, one of them suffering a nervous breakdown. In addition to losses among company commanders, numerous platoon leaders and platoon sergeants had fallen victim to the cold, or the enemy, or combat exhaustion.

Yet despite the heavy casualties, the Americans at Wahlerscheid felt a sense of accomplishment. They had cracked the German front line. Their victory had occurred at the forefront of a major U.S. Army offensive aimed at capturing a series of dams on the Roer River. The conquest of Wahlerscheid removed the first obstacle on the way to the dams.

After Wahlerscheid fell, the 1st Battalion established its command post in one of the captured bunkers. As the final hours of December 16 ticked away, Hancock walked outside the bunker and surveyed the surroundings. The night was uncharacteristically clear and quiet. He looked far to the south and saw a blue cloudbank stretching for miles and miles. Flashes of light illuminated it, and the rumble of thunder droned on without lull. The spectacle resembled an electrical storm, but it was entirely manmade, all of it created by artillery. Hancock surmised that an attack must be in progress.

He ambled back inside the bunker to tell the battalion commander about the artillery show. The commander was fast asleep, taking an overdue nap. About then, a field telephone rang. The regimental executive officer was on the line, and he wanted to speak with the commander. Preferring not to wake his boss, Hancock took a message instead. The executive officer said the enemy had launched an attack to the south and had penetrated the American line at several points. He then said the 9th Infantry might have to abandon Wahlerscheid and move south in the morning to help stop the German assault.

The battalion commander, Lt. Col. William Dawes McKinley, woke up and heard Hancock on the phone. News of a possible retreat from Wahlerscheid dismayed McKinley, but he went about making plans for a possible withdrawal.

Hours later, on the morning of December 17, McKinley received an urgent summons to the regimental command post. The entire 9th Infantry had orders to pull out. McKinley’s men were to defend an area five miles to the south, in pastureland near Rocherath, Belgium.

Word of the pullout spread among the troops like a prairie fire. After all the terror and death at Wahlerscheid, they were going to give up the place without a fight. It seemed like a bad dream. The men began referring to Wahlerscheid as Heartbreak Crossroads.

Nobody in the 9th Infantry knew the full extent of the German attack to the south. Nobody knew that Hitler had secretly mustered a force of nearly 1,000 tanks, 2,000 artillery pieces, and 200,000 men.

The soldiers of McKinley’s battalion faced real peril and had no inkling of it.

On December 17, 1944, McKinley and his men began the chore of moving south to meet the German attack. First, the battalion had to disengage from Wahlerscheid without the enemy becoming aware that an American pullout was under way.

According to standard procedure, each rifle squad left three of its 12 soldiers behind (although few squads still had 12 men). The rear guard darted up and down the line, firing from numerous positions to give the appearance of normal operations. Mortar men from Company D and howitzer crews from the 15th Field Artillery Battalion added to the ruse by laying down barrages on the enemy.

Led by Major Hancock, the rear guard gradually pulled out and joined the tail of the battalion column. Before leaving, the major used a thermite grenade to burn a broken-down jeep. He and others had filled it with rifles left behind by soldiers who had become casualties. McKinley’s men were the last soldiers of the 9th Infantry to leave Wahlerscheid.

The infantrymen marched south through fog and mist. They crossed into Belgium from whence they had originally come. Each man trudged along with bleary eyes and a sad slouch. The long line of GI boots churned a path through the snow and muck on the main road to Rocherath. The evergreen forest on either side of the road seemed to stretch on forever, but finally the troops emerged from the woods.

A little farther south, at an intersection known as Rocherather Baracken, the men came upon Maj. Gen. Walter M. Robertson, commander of the 2nd Infantry Division. He flagged down McKinley. The general apprised his subordinate of all available information regarding the German attack. Robertson then directed McKinley to move his battalion and secure a crossroads northeast of Rocherath and defend it against enemy forces pushing in that direction. The general provided trucks, enough to haul about half the battalion.

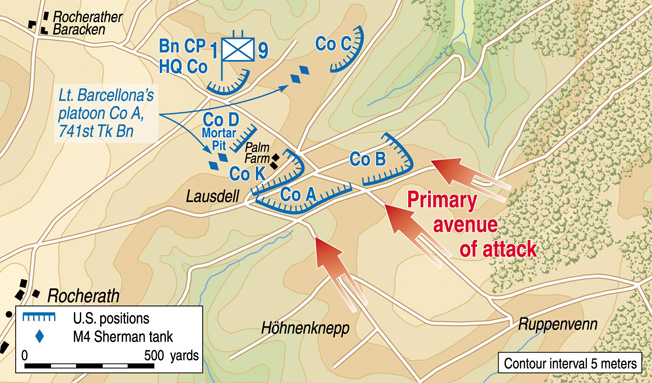

Robertson had already sent three elements of the 3rd Battalion to the crossroads. They included Company K, a section of machine guns from Company M, and the Ammunition & Pioneer Platoon from Headquarters Company. McKinley received instructions to take command of these units and attach them to his battalion.

The crossroads itself lay amid a patchwork of cow pastures, which local residents called Lausdell. Waist-high hedgerows separated one pasture from another and served as fences. Two buildings stood at the crossroads, a gray-shingled farmhouse and an adjacent barn. The property belonged to Albert and Franzika Palm, a dairy farmer and his wife. Like most civilians, the Palms and their children had moved away when the area became a front-line sector in early autumn.

Many of the Infantry Soldiers Looked Punch Drunk, Stupefied by What They had Witnessed.

The house stood derelict when soldiers of the 9th Infantry found it. Captain Jack A. Garvey, commander of Company K, established his command post in the cellar. He positioned the A&P Platoon to his right rear, and he set the Company M machine gunners on his flanks.

All the while, the rattle and pop of small-arms fire emanated from the forest less than a mile east. Bedraggled soldiers exited the woods and hustled toward Lausdell. Some of them wore the Indian Head patch of the 2nd Infantry Division and others wore the Checkerboard patch of the 99th Infantry Division. Many looked punch drunk, stupefied by what they had witnessed. Their units had nearly ceased to exist, crushed by the steel might of enemy tanks. The men told stories of horror and catastrophe. Some of the soldiers stayed to fight alongside McKinley’s troops, others fled.

When McKinley arrived at Lausdell, the commander of his headquarters company had already selected an abandoned dugout to use as the battalion command post. It had once belonged to the 372nd Field Artillery Battalion, part of the 99th Division. Earlier in the day, the artillerymen had abandoned firing positions at Lausdell, taking all their howitzers with them.

The dugout that McKinley occupied sat well to the rear of the Palm farmhouse. Inside the log-covered hole, the artillerymen had left a wooden table, upon which McKinley’s staff placed maps and a telephone. The colonel himself received another summons to regimental headquarters, leaving Bill Hancock and Captain Glenn M. Harvey, battalion operations officer, to plan the defense of Lausdell.

Harvey and Hancock placed two of the battalion’s three rifle companies in front of Company K. Company A dug in on the right of the main road that cut through Lausdell. Company B dug in on the left. The two units occupied pastures that earlier in the day had been home to Cannon Company, 393rd Infantry, another 99th Division outfit. The men of Companies A and B attacked the ground with their entrenching tools, shoveling out foxholes behind hedgerows. Some of the soldiers took over holes left behind by Cannon Company. The commander of Company A, 1st Lt. Stephen P. Truppner, settled into a deserted dugout. His Company B counterpart, 1st Lt. John S. Milesnick, had only a foxhole.

Harvey and Hancock placed Company C in a reserve position on the battalion left flank, well behind the other two rifle companies. Company C had suffered the heaviest casualties at Wahlerschied and had the least number of able-bodied men. Its new commander, Captain Arnold E. Alger, had transferred in from battalion headquarters.

Besides positioning the rifle companies, Harvey and Hancock gave deployment instructions to Captain Louis C. Ernst, commander of Company D. Ernst paired his two machine-gun platoons with Companies A and B. He placed his mortar platoon along a hedgerow directly behind the Palm farmhouse, and he established his command post near the mortars.

The hour was 5:45 pm, and the day had already lost its light.

Back at battalion headquarters, McKinley returned from regiment and reviewed the defensive plan devised by Harvey and Hancock. He approved it and then met with his company commanders.

Years later, Hancock recalled the colonel’s words: “Gentlemen, this is it. We have a Panzer Army coming toward us down the road you see in front of us. They have been seen by our scout airplanes, and they should be here within the next hour. Our mission is to defend the crossroads at all costs. I know you are in position now. When you return to your companies, make sure that everyone in your command understands exactly what ‘at all costs’ means.”

McKinley spoke with the self-confidence of a man who knew his job to a farthing. He turned to his operations officer and said, “Harvey, form 22 bazooka teams. We’re going to be on the defensive, but we’re also going to be attacking.” McKinley then instructed his supply officer to provide extra bazookas and rockets should Harvey require them.

The colonel also directed his company commanders to assemble mine-laying teams responsible for planting antitank mines on all roads that enemy armor might use. But there was a complication. McKinley had received word that armor of the U.S. 741st Tank Battalion might be in the area. The mine layers had to hold back, pending a confirmed sighting of German tanks. Nobody wanted to blow up an American tank by accident.

While the battalion commander spoke to his company commanders, his artillery liaison officer, 1st Lt. John C. Granville, sat just inside the entrance of the command post and agonized over a stroke of bad luck. “I was trying to make contact with the 15th Field Artillery Battalion,” Granville recalled. “But my radio wouldn’t work.”

Minutes later, Granville’s fortune changed. “Lieutenant John W. Cooley, a forward observer with Battery A of the 15th Field Artillery, arrived at the CP to ask for instructions regarding artillery support. I told Cooley that my radio was out and that we had to use his radio to make contact with the 15th and, since he would be without any means of communication, he was to stand by as my backup. Lieutenant Cooley and his crew then prepared to dig in about 20 yards behind the battalion CP.”

Wearing a headset, Granville spoke into the microphone of Cooley’s radio. It was a bulky SCR-610, the standard FM set used by artillerymen. He soon reached the Fire Direction Center of the 15th Field Artillery and learned that someone had inadvertently compromised the code used to encrypt map coordinates. It consisted of letters that corresponded to numbers. The FDC staff created a new one. “I was to use my own first and last name, not using any letter twice, as a substitute for the compromised code.”

Soon after Granville received the new code, he opted to discard it and transmit all coordinates in plain English. The St. Louis, Missouri, native had been in combat since Normandy, and he knew that in a pitched battle he would have no time to fiddle with encryption. Every second mattered.

Visibility dwindled to almost nil as night and fog enveloped the Lausdell defenders. The men strained to hear any sign of the enemy. Nothing stirred.

The SS Men Were “Talking and Joking Like the War was Over,” He Recalled. They Seemed Unaware They Were in the Midst of an American Infantry Battalion.

The stillness lasted until 7:30 pm when, from the east, the men heard the hum of engines and the distinctive squeak and clatter of tank tracks. Four armored vehicles approached. The company commanders had already informed the troops that friendly tanks might be in the area.

As the vehicles drew nearer, the GIs thought the machines were friendly. False assumption. They were Jagdpanzers from the 1st Company of SS Panzerjäger Abteilung 12, and each had an escort of foot soldiers from the 25th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment.

Sergeant Joseph Busi of Company D lay beside the dirt road looking at the grenadiers and Jagdpanzers as they passed by several feet in front of him. The sergeant, a coal miner from Pennsylvania, watched in open-mouthed amazement. The SS men were “talking and joking like the war was over,” he recalled. They seemed unaware they were in the midst of an American infantry battalion.

The grenadiers and tanks passed through without a shot fired. They disappeared into the night and continued on toward Rocherath.

Back at Lausdell, scores of GIs shook their heads in disbelief. Soon thereafter, the Americans heard a second group of tanks approaching. Nobody doubted they were German. As the machines rumbled closer and closer, Busi lay mines on the road, as did two other members of his company, Sergeant Charley L. Roberts and Pfc. Harlin E. Coffinger.

The lead tank was Panther 135 from the 1st Company of the 12th SS Panzer Regiment. It reached the crossroads at the center of Lausdell, where it struck one of the mines laid by Coffinger. The blast disabled 135, breaking its left track, which peeled off as the tank ground to a standstill.

Firing erupted. The five-man crew of 135 cut loose with its 75mm cannon and two machine guns. The spray of bullets killed Tech. Sgt. Charlie A. Reimer and Staff Sgt. Billy Floyd, both members of Company A. The unfortunate pair fell as they exited the dugout that served as the Company A command post. Amid the fracas, Panther 127 clanked up to the crossroads. It bypassed the crippled 135 and began turning left toward Rocherath.

Just then, Private William A. Soderman of Company K rose from behind a hedgerow. The former butcher from Connecticut shouldered a bazooka and faced the enemy tank at close range. He squeezed the trigger of his weapon, and a rocket streaked through the air. The wrenching explosion shattered a track link, and the tank rolled to a halt beside Soderman’s position. He had brought down a Panther with a single shot.

The crew inside 127 began firing high explosive shells. The turret rotated a few degrees, and the main gun barked out a shell. Another shot followed after the crew cranked the turret around a few more degrees. The enemy gunner sniffed out targets, pounding any location where he spotted movement.

Busi started launching rifle grenades at 127, hoping to stifle its big cannon. Many of his grenades bounced off, but one of them detonated along the base of the turret. The blast sent out a long tongue of fire. “The turret stopped rotating and didn’t move again,” Busi recalled. Crewmen quickly emerged from the maimed beast, and GIs everywhere opened up on them. Shots rang off the steel hull as the crewmen perished one after another.

Machine gunners from Company D participated in the killing. The squad, led by Corporal Sydney L. Plumley of West Virginia, squirted a steady stream of bullets at the tank. His squad also engaged German infantrymen, who had begun appearing out of the gloom. Plumley worked the trigger, while his assistant gunner fed belt after belt of ammunition. Their shooting drew more attention than a circus spotlight.

As Plumley’s gun blazed away, the crew of 135 remained inside their vehicle and carried on the fight. Their cannon shells ignited hay inside the Palm barn and turned the structure into a flaming pyre. The inferno increased visibility at Lausdell, and the Germans took advantage of it, shooting point blank at whatever targets they could locate. According to Busi, “They were traversing the gun and firing at anything.” One shot cut down Plumley and his assistant, Pfc. Harry Hooper. Another shot clobbered the machine gun operated by Pfc. Howard Ammons, who died along with his assistant, Pfc. Frank J. Cudo.

The situation demanded quick action. “We knew something had to be done as we would all be killed,” recalled Harlin Coffinger.

Sergeant Roberts, a 30-year-old Texan, said, “Let’s burn the damn thing!” He and another Texan, Staff Sgt. Odis Bone of Company B, retrieved a five-gallon can of gasoline from an American vehicle abandoned nearby.

Bone and Roberts crept up behind 135, accompanied by Busi. Bone had the gasoline can, and Roberts had a white-phosphorous grenade. After opening the can, Bone raised the heavy container with help from Busi, and the two heaved it onto the engine deck. Gasoline gurgled out. The tank commander inside became aware of the danger, perhaps seeing the Americans through one of his periscopes.

The three GIs watched the turret hatch slowly open. It rose just enough for the commander to toss out a grenade, which hit the side of the tank and bounced onto the road. Bone and Roberts dropped to the ground just as it exploded. The blast injured Roberts in the hand. Ignoring his wound, he leaped to his feet and flipped the phosphorous grenade onto the engine deck. The gasoline erupted into flames, and the fire beat red against the black sky.

“Our Troops Along the Road Just Riddled Them,” Bone Later Recalled. The Bodies of Two Lifeless Germans Tumbled off the Tank and Landed Beside Him.

Tracer bullets crisscrossed the air, and Bone surmised he would be hit if he tried to run. He elected to seek cover alongside the tank. He urged Roberts to do the same, but Roberts ran and somehow survived.

The crew of 135 realized their tank had become a death trap, and they made several attempts to escape. Each time trigger-happy Americans kept them pinned inside. The crew eventually became desperate and bailed out despite the fusillade of bullets.

“Our troops along the road just riddled them,” Bone later recalled. The bodies of two lifeless Germans tumbled off the tank and landed beside him.

Against near impossible odds, one crewman managed to escape by jumping off the left side of the tank. Busi caught sight of him as “he ran like hell back toward German lines.” The flames illuminated a white bandage wrapped around his head.

When the hail of small arms projectiles subsided, Bone sprang up but took a moment to grab a field cap belonging to one of the dead Germans. He then made a beeline to the Company B command post, established along a nearby hedgerow. He gave the cap to a lieutenant who said, “Take it back to battalion.”

Bone raced some 400 yards to the dugout being used as the battalion command post. He showed the cap to McKinley and several members of his staff. They immediately recognized the insignia on it as being SS and asked how he obtained it. Bone described the fiery incident at the crossroads. One staff member promised him a Silver Star, but that meant little to the sergeant. In his mind, survival was the only measure of success.

Meanwhile, two other tanks had advanced behind 135 and 127.

Lieutenant Roy Allen and Technical Sgt. Ted A. Bickerstaff of Company B pulled a “daisy chain” of eight antitank mines across the road in front of the tanks. Bullets flicked up dirt around the two men as they armed the mines.

Alert to the danger, the tank drivers veered into adjacent cow pastures. The huge battle wagons slewed mud and hunks of sod as they sideslipped the daisy chain. American soldiers clutching bazookas stalked after them. The commander of Company B was among the hunters. He suffered a nasty leg wound while in pursuit but nonetheless remained in charge of his unit, refusing medical evacuation.

German infantrymen had accompanied the tanks, and some of the soldiers crept among the American foxholes. One SS man jumped in the hole occupied by Pfc. Roberto Gonzales of Company D. The startled GI fled and reported the situation to his platoon leader, 1st Lt. Allyn H. Tedmon of Fort Collins, Colorado.

“Did you kill him?” Tedmon said.

“No.”

“Go back and kill him.”

Gonzales carried out the order, using a trench knife to dispatch the enemy soldier.

Tedmon led the 2nd Heavy Machine Gun Platoon, and he had established his headquarters in a shell hole. Eighteen men served under him, and his little band of defenders pelted the German infantry with machine-gun bullets.

Three riflemen from Company A did the same. Pfcs. Harry Stemple, William L. Adams, and Rodney M. Jennings climbed aboard Panther 127 and took over one of its machine guns, probably the antiaircraft MG 34. The men soon had it spitting bullets at the enemy.

But the Germans kept coming.

The commander of Company B sighted more armor approaching, and each tank had an infantry escort. He radioed the news to McKinley’s command post, and the colonel put Lieutenant Granville to work orchestrating artillery support. Granville transmitted his initial call for assistance at 8:36 pm. He began searching the road with shellfire, starting close to Companies A and B and shifting the barrage back toward the forest.

He later recounted his actions: “My first requests for fire were given in an orthodox manner with ‘sensings’ that fire was so many yards short or over, or so many yards right or left. Of course, these were actually the sensings of the infantry personnel involved as relayed to McKinley.”

Shells plunged down with a piercing wail as salvo after salvo hit the enemy. The German tanks and infantry halted. The Lausdell defenders heard wounded enemy soldiers calling for medical attention. “Sani! Hilfe!” they cried.

The commander of Company A soon reported more tanks approaching.

Granville shifted the artillery bombardment and stymied the new threat.

At 10:30 pm, the Company A commander again reported tanks—Panthers and Jagdpanzers. This armored assault converged on Lausdell from three directions. It was the heaviest attack of the night.

Granville described his response: “As the action thickened, I threw all orthodoxy to the wind and, in very unmilitary jargon, called for fire ‘on the right’ or ‘on the left.’ Now those sorts of commands would have made no sense had I not been able to give the precise coordinates of our command post as well as the coordinates of the first target. But, having established those two points, I knew that a line had been drawn showing the relationship of our position to the network of roads.”

The staff at the fire direction center translated Granville’s calls into precise coordinates and then assigned targets to the 12 howitzers of the 15th Field Artillery. Target assignments also went out to six other artillery battalions, which General Robertson had thrown into the fight.

Granville (call sign “Two Four One”) pleaded for everything his FDC could scrape together, and he yelled into his microphone, “If you don’t get it out right now, it’ll be too Goddamn late!”

The seconds crawled by.

I Screamed into the Radio, ‘Get off My Channel, You Kraut Son-of-a-Bitch!’”

Then, to the rear of Lausdell, the horizon lit up like dawn. Granville heard the distant rumble of howitzers followed by the whoosh of shells hurtling overhead. The wave of projectiles exploded in a horrible cyclone of steel and fire. Shock waves from the bursting shells quaked the earth as the detonations merged into a single deafening din. Everywhere the enemy attackers turned, they saw the bright face of Death.

Granville’s calls had opened the gates of hell, and he kept hollering for more and more shells. But while transmitting requests, he encountered interference.

“During the height of the artillery barrage, a German tank commander broke into our radio channel. He was giving excited commands to his forces, and he and I were talking at the same time over the same radio channel. This was too much for me to stomach. I screamed into the radio, ‘Get off my channel, you kraut son-of-a-bitch!’”

Granville subsequently learned that everyone at the FDC had also heard the German voice. Private Max W. Burian, a German-speaking member of the unit, grabbed a microphone and mimicked the radio lingo used by the enemy. “He transmitted a message directing the Panzers to return to their assembly area,” Granville explained. “I don’t know if any of that worked, but I was probably cussing him out, too.”

By midnight, the wild melee had subsided, and the sour stench of TNT hung in the air. Panthers 127 and 135 stood at the center of the battlefield like a pair of tombstones. The Germans had withdrawn to regroup and marshal more forces.

Hitler’s great attack struck along an 89-mile front and overwhelmed numerous American units. The 2nd Division had faced envelopment, but the successful defense of Lausdell on December 17 gave the division time to maneuver.

The 38th Infantry, sister regiment of the 9th Infantry, deployed around Krinkelt-Rocherath and moved in behind McKinley’s troops. Linemen spliced together a telephone wire from McKinley’s command post to the 38th Infantry. The colonel obtained information about the defensive line forming behind his battalion. The men at Lausdell would eventually withdraw through that line but not before receiving permission. For now, they had to continue holding Lausdell.

McKinley gained assistance from a battle-worn battalion of the 99th Division. Its commander, Lt. Col. Jack G. Allen, received instructions to tie in on McKinley’s left flank. The arrival of Allen’s force, albeit badly depleted, allowed McKinley to move his Company C from its reserve position. The company marched to ground on the far right flank. There, on the outskirts of Rocherath, the men had instructions to guard against a return of the grenadiers and Jagdpanzers that had passed through Lausdell just before the battle began. The soldiers of Company C found no Jagdpanzers but engaged in a skirmish and bagged one enemy prisoner. The soldiers also encountered GIs of the 38th Infantry, who were now taking control of the area. The company commander soon had orders to turn his men around and move back to the reserve position.

Throughout the predawn hours, Lieutenant Granville called for harassing fire on the Panzer-infested woods to the east. Artillery shells interdicted roads, trails, and anywhere the enemy might be massing forces.

Under the shellfire, German armor and infantry girded for renewed combat. Jagdpanzer crews hunkered down and awaited orders. Crewmen from the 1st Company of the 12th SS Panzer Regiment also waited, as did crewmen from the 3rd Company, which had reached the forest during the night and had 14 brand-new Panthers. (The 1st Company had started the battle with the same number of new vehicles.)

The renewed German assault broke on Lausdell before sunrise. The 1st Company led the way through the fog and dark. “You could hear the tank engines roaring in the distance,” Major Hancock remembered. “It sounded like a hurricane coming.”

With McKinley at his side, Lieutenant Granville shouted for all the artillery fire his FDC could muster in front of Companies A and B. Granville recalled what happened next: “McKinley handed me his radio receiver. From the other end came an admonition to me: ‘You’re killing my men. You’re blowing them out of their holes.’ I immediately ordered fires in that sector moved back one hundred yards or so. To this day, I could not tell you which officer I was talking to. I was sick at heart.”

Although the shelling inflicted friendly casualties, it blunted the German attack. The tanks and grenadiers turned tail and fell back.

Daytime slowly arrived, and the sky shifted from black to shades of gray. In the morning light, the Germans pushed forward again. Like a giant battering ram, an extended column of tanks plowed toward Lausdell. Hancock described their attack formation: “They closed up just like boxcars on a railroad track, practically bumper to bumper.” Grenadiers marched alongside the column, each man with his weapon at the ready.

Artillery shells began raining down on the phalanx of men and machines, but it wormed its way to within 20 feet of the American foxholes.

William Soderman darted along a ditch to engage the oncoming tanks. He leaped onto the road and pointed his bazooka at the lead vehicle. His rocket disabled it.

Meanwhile, the German foot troops had fanned out. Grenade battles erupted, as did hand-to-hand combat and bayonet fights. Soderman killed at least three enemy soldiers with another shot from his bazooka. He used his last rocket to disable another tank. As he scrambled for cover, machine-gun bullets from the tank tore open his right shoulder. He dragged himself a short distance before two buddies helped him off the battlefield.

Not all the Americans displayed courage like Soderman. Six or seven Company B men fled in panic. McKinley heard about it over his radio, and he charged out of his command post. He intercepted the men and sent them back to their unit. Thirty minutes after daybreak, the commander of Company A reported via radio that German forces had swamped his company, but his men were hanging on despite the dire predicament.

Panthers prowled around Lausdell, blasting foxhole after foxhole. One shell exploded near the position occupied by Rodney Jennings and Harry Stemple. The blast peppered Stemple with fragments, and he bled to death in Jennings’s arms.

Lieutenant Truppner, the Company A commander, made one last radio transmission. He requested artillery fire on his own position. His troops ducked into their holes as howitzer shells burst pell-mell throughout the area. The explosions rocked the landscape with concussion and left men bleeding from their ears.

One projectile struck the roof of a Panther turret, penetrating its armored skin and setting off the ammunition stowed inside. The shattering blast made the 47-ton behemoth look fragile. Great hunks of steel somersaulted through the air, and a mushroom cloud billowed upward. The lucky hit left torn and twisted metal strewn all over, but the explosion did little to stem the enemy tide.

At 10 am, McKinley received permission to withdraw around noontime. By then, troops of the 38th Infantry would have a new line behind Lausdell. McKinley had one stabbing worry. How could he accomplish a retrograde movement with his men locked in close combat? The enemy would blast his soldiers in their backsides if they attempted to disengage. Artillery as a means of cover was problematic. It might hold down the Germans but would butcher the withdrawing defenders as they rose from their holes. What to do? The officer in charge of the battalion antitank platoon spotted an answer churning in the morning mist.

First Lieutenant Eugene V. Hinski sprinted toward four American tanks roving along the Rocherath-Wahlerscheid road. He shouted at the man in charge, 1st Lt. Gaetano R. Barcellona from San Antonio, Texas.

“Do you want to fight?” Hinski said.

“Hell, yes! That’s what I’m here for.”

Excited hands pointed the eager tank commander to the battalion command post, where McKinley rejoiced at the sight of the four lumbering friendlies.

The 29-year-old tank officer led the 2nd Platoon of Company A, 741st Tank Battalion. He sported a bushy mustache and had a reputation for boldness. Several months earlier, he had received the Distinguished Service Cross for his D-Day exploits.

The Panther Cut Loose Again but Missed. The Sergeant Never Flinched. And Then—Wham—It All Ended.

McKinley, his operations officer, and Barcellona hatched a plan to use the armored platoon for a counterattack. The maneuver would permit the remaining Lausdell defenders to retreat. The planners decided to split the tank platoon in half, two vehicles north of the withdrawal route and two vehicles south of it. After a 30-minute artillery barrage, the northern pair moved out at 11:45 am. They served as decoys, attracting the eyes of the Panther crews.

The distraction allowed Barcellona’s other two machines to move out and creep close enough to make use of their armor-piercing shells. The tank gunners scored two hits on one enemy vehicle and three on another (the victims may have been Panthers 127 and 135, already out of action). Caught by surprise, two other Panthers bolted toward the twin villages. Barcellona claimed a hit on one of them. Afterward, his platoon withdrew to reassemble for another attack.

With the Panther menace momentarily dispersed, McKinley’s men, those not already overrun, pulled their noses from the muck and began falling back. The commander of Company B, Lieutenant Milesnick, rousted his men and guided them away despite his being hobbled by a leg wound. Only after leading his men to safety did he consent to medical attention and a trip to the 5th Evacuation Hospital.

Many of the retreating Americans escaped under covering fire provided by a lone Company D machine gunner, Technical Sgt. James L. Bayliss. He carried a heavy machine gun to an advantageous position and put his weapon into action. The career soldier from Cedar Bayou, Texas, swept the enemy infantry with bullets.

As he hammered out .30-caliber slugs, German armor again converged on Lausdell. The crew of a Panther spotted him and unleashed a shell. The projectile flew wide. Bayliss ignored it and stayed behind his weapon. The Panther cut loose again but missed. The sergeant never flinched. And then—wham—it all ended. He died in a blinding flash as a tank shell found its mark.

Joe Busi and two of his men fell back to the battalion command post. One of McKinley’s lieutenants directed Busi to a jeep loaded with ammunition and a machine gun. The sergeant fetched a couple boxes of ammunition. One of his men hoisted out the gun, and the other grabbed a tripod for it. The threesome had instructions to set up the gun at the far end of a long hedgerow and provide suppressing fire. The soldier carrying the gun led the way. Private Joseph Popielarcheck had the tripod. Busi cautioned him, “Stay down below that hedge. Don’t let ’em see you.”

Popielarcheck, a former paratrooper, lugged the tripod on his shoulders. “He started off real low,” Busi remembered. “But then—I guess maybe his back was hurting—he rose up higher and higher. I saw him standing straight up after awhile.”

The Germans also saw him and began yelling. Busi realized the danger and screamed, “Get the hell down!” Adrenaline pumping, he tore after Popielarcheck and dove to knock him flat. But an enemy shell won the race. The blast cut Popielarcheck in half and knocked Busi unconscious.

After regaining his senses, Busi looked around, and his eyes locked on a pair of severed legs clad in paratrooper pants. He also felt pain radiating through his own right leg and hand. Shell fragments had stung him. Blood covered his face and uniform, most of it splatter from Popielarcheck. The injured sergeant crawled away to the battalion command post, where a medic dressed his wounds and pointed him toward the rear.

Busi limped away, moving from foxhole to foxhole as bullets whizzed overhead. He chanced upon a large hole containing four or five wounded soldiers, men who had suffered everything but death. He joined them and said, “Guys, we might as well pray. The Germans are coming like crazy with big tanks. They’re gonna kill us all.” Everybody started to pray.

The nerve-grinding rumble of tanks soon followed.

Prepared for the worst, Busi poked his head above the lip of the hole. The tanks belonged to Lieutenant Barcellona’s platoon. They were attacking in an attempt to spring free the remaining Lausdell defenders. Medics arrived shortly thereafter and evacuated the injured men to a barn at Rocherather Baracken, which served as the battalion aid station. Busi eventually became a patient at a hospital in England and never returned to the 9th Infantry.

Many others also never returned to the 9th. They became prisoners of war, and their ranks included Captain Garvey of Company K. From inside the Palm farmhouse, he watched German infantrymen capture his soldiers and most of Company A. He remained in the house with several wounded men until an enemy tank parked outside the building and trained its cannon on the front door. Garvey threw in the towel and saved the lives of everyone in the house.

McKinley, Captain Harvey, and Captain Ernst were the last men to escape Lausdell. As they hightailed it out, German soldiers shouted at them: “Hände hoch! Hände hoch!”

Jennings had no Idea He had Received the Silver Star Until 2005 When This Author Informed Him.

The next day, the defenders who had dodged death and captivity retreated toward Elsenborn, Belgium. Each of the exhausted men felt numb and hollow as an empty shell casing. Yet, McKinley could see beyond the agonies of the present day. While shambling along a sodden road, he said to Captain Ernst, “We’re treading on a page of history.” Ernst glanced down at his boots. “All I see is mud, Colonel.” McKinley shook his head, smiled, and trudged on.

The first head count after the retrograde found only 217 men and officers, although other soldiers made their way home in the coming days. The least fortunate never lifted their faces from the mud and snow. Graves Registration teams recovered 31 fallen GIs from Lausdell after the 2nd Division reclaimed the area in February 1945.

The casualty roll also included 146 soldiers who found themselves on the rueful road to prisoner of war camps in Germany. All but 18 of the soldiers belonged to Companies A and K. Among the internees, Garvey and Truppner were the highest ranking. They became residents of Stalag XIIID and survived the war. Only two of McKinley’s men died in captivity.

Days after the men became prisoners, New York Times correspondent Harold N. Denny began interviewing those soldiers who had avoided captivity. His writing invested the Lausdell defenders with heroic stature for their role in what newspapers called the Battle of the Bulge. Denny authored a front-page article with the headline: “U.S. Battalion’s Stand Saves Regiment, Division and Army.” Those words represented more than journalistic hyperbole. The men under McKinley’s command, and their comrades in the artillery, had staved off the 12th SS Panzer Division for 18 hours. Without that delay, the enemy would have been in position to inflict a devastating defeat upon the 2nd Division and the U.S. First Army.

During those crucial hours, McKinley’s soldiers upheld the motto of the 9th Infantry Regiment: “Keep up the fire.”

McKinley’s battalion and its attached units received a Presidential Unit Citation in April 1945. Individual awards among the men are listed in the box above.

Jennings had no idea he had received the Silver Star until 2005 when this author informed him. Congressman John Murtha’s staff subsequently helped the 83-year-old veteran receive his medal, albeit 60 years late.

McKinley’s award encompassed the Lausdell and Wahlerscheid actions.

Plumley had returned to duty eleven days before his death, having spent months convalescing from wounds suffered in France. His buddies called him “Pluto” because his nose resembled that of the Disney character.

McKinley recommended Gaetano Barcellona for a Silver Star, but higher headquarters downgraded it to a Bronze Star.

Odis Bone of Company B never received the Silver Star promised him.

Bill Warnock is a U.S. Air Force veteran and author of The Dead of Winter, a recently published book chronicling present-day efforts to recover the remains of missing U.S. soldiers killed during the Battle of the Bulge.

From a Belgian citizen who wasn’t born until much later after the Battle of the Bulge, I say thank you so much to this Golden Generation of young men who came to save us from the Nazi boot. Once in a while I pay my respects in the city of Bastogne.

Vogel Ip is the name of the Western Command post above the Roer dams South of Aachen by about 20 miles. The site is very impressive with a dozen tank ramps for the Panzers to place on to fire up over the dams towards the West. It was along with the Berschtegarden and the Berlin Wolf’s lair a major command area. After realizing that Allied bombers could strike it early in the war, the place was abandoned. Today it is a large tourist draw and a great place to visit for WWII history.