By Peter McQuarrie

In the autumn of 1943, the U.S. Navy had regained strength after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and plans were made for a big offensive in the Pacific. Starting in the eastern end of the line of Japanese outposts in the Gilbert Islands and pushing north and east, through the Marshall and Mariana Islands, to the Philippines and continuing all the way to Japan.

The objective of the first move, Operation Galvanic, was to capture the Japanese-held Gilberts and use them to provide strategically located U.S. bases for attacking and capturing the Marshalls and Marianas to the north. It was from their Marshall Islands bases that the Japanese had first invaded the Gilberts and Nauru in December 1941.

If successful, Operation Galvanic would eliminate the risk of the Japanese developing any new bases further to the east or south and ensure secure lines of communication between the United States mainland, Hawaii, and the South Pacific countries of Australia, Fiji, and New Zealand. American bases in the Gilberts would also allow easy bombing access of nearby Nauru and Ocean Island, which were occupied by Japanese forces and difficult to invade from the sea because of high cliffs around their coasts. Regular bombing would prevent the use of the airfield on Nauru and ensure that these islands were neutralized and starved into surrendering.

Operation Galvanic was to involve the concurrent capture of Tarawa, by U.S. Marines, and Makin by U.S. Army troops. The small Japanese military post at Abemama Island would also be captured by the Marines. The Japanese had built an airbase at Tarawa and although they had surveyed Abemama and Makin for airfields, none had been built on those islands. The U.S. wanted to construct bases for aircraft on both islands in addition to Tarawa.

In the preparation for Galvanic, the U.S. needed to have the use of other small islands in the Central Pacific to be the stepping stones to get ships and aircraft, men and equipment across the ocean to the Gilberts.

The Pearl Harbor attack had placed an urgency on a South Pacific aircraft ferry route, and work had commenced quickly on building airfields on Christmas and Canton Islands for a route: Hawaii—Canton Islands—Fiji—Australia with Christmas Island as an alternative to Canton. The airfield at Canton was completed on December 28, 1941, and the airfield on Christmas Island in January 1942. The route to the Gilberts for aircraft taking part in Galvanic would eventually be from Canton Island to Funafuti in the Ellice Islands, then to Nanumea, the northernmost Ellice Island, and the nearest to Tarawa.

Also in the Central Pacific, in the Phoenix Islands, the Americans completed a runway on Baker Island in September 1943. A small desert island near the equator, Baker could also be used as an alternative to Canton Island as an aircraft refueling stop if required. Howland Island was another island in the Phoenix group which could be used. The U.S. Navy had constructed a runway on Howland in 1937. This had been provided as a refueling stop for Amelia Earhart, in her attempt to be the first woman pilot to circle the globe. She went missing on the long flight between Papua New Guinea and Howland. Howland was a Central Pacific Island, claimed as a possession by the United States.

The Ellice Islands were a vital strategic link situated between British Fiji in the south and the equatorial Gilbert Islands to the north. A chain of nine islands and atolls, spread out north to south over 700 miles of ocean, bases in the Ellices would provide air and naval support as close as possible to the Gilberts. In October 1942, U.S. Marines occupied Funafuti Atoll in the south of the Ellice Group, constructing an airfield suitable for heavy bombers and modifying the atoll’s lagoon to make it a safe harbor for large ships.

With more than 200 warships—and 20,000 crewmen—at sea for weeks thousands of miles from their fleet base in Hawaii, Operation Galvanic posed a logistics and support problem for the Navy. Funafuti’s large lagoon would form a supply and staging point for the food, medical services, munitions, and fuel. The Navy created Service Squadron 4 (SERVRON 4) as Funafuti’s mobile naval base, the first ever floating base in the history of naval warfare. Some Japanese-held islands would be attacked, but the invasion would leapfrog over others, leaving them to “wither on the vine.”

In August 1943, U.S. Marines began to construct bases at Nukufetau and at Nanumea, the nearest Ellice island to the Gilberts, 500 miles south of Tarawa. The first American Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers landed on the newly finished airstrip on Nukufetau at the end of October, and Nanumea became operational for bombers on November 12, just eight days before the commencement of Operation Galvanic.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, with the U.S. Pacific Fleet out of action, the only ships able to retaliate were submarines. Their directive was to execute unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan. All submarines were placed under the direct command of the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet (CinCPac), and they acted alone during the first two years of the war while the surface fleet was being repaired.

The fleet submarines were designed as advance scouts, but they had the speed, endurance, and weaponry to attack Japanese shipping throughout the Pacific. For a country with few natural resources of its own, these sea routes were the lifeblood of the Japanese war effort, bringing in oil, coal, iron, and also food and it needed to supply its military outposts throughout the Pacific.

American submarines tightened their grip on these remote outposts as they sank increasing numbers of merchant ships. More than half of all Japanese merchant ships sunk in World War II were as a result of U.S. submarine action. Along with other Pacific bases, the Japanese base at Tarawa suffered when supplies failed to arrive. They did not receive the cement and reinforcing steel they needed to complete their concrete bunkers and so had to make them of sand and coconut logs alone. Their army tanks might have been useful weapons during the Battle of Tarawa, but they did not have enough fuel to power them.

On May 19, 1943, the submarine USS Pollack (SS-18), on patrol between the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, torpedoed and sank the Japanese freighter Bangkok Maru. The ship was carrying artillery and 1,200 Japanese combat troops to reinforce the Tarawa garrison. Reinforcements never arrived, and the Tarawa garrison of 2,500 fighting men had only construction workers and Korean laborers to assist them against Operation Galvanic. In hindsight, the battle for Tarawa could have been even worse had it not been for the work of the U.S. submarines to Japanese strength there.

The US had 10 submarines in support of Operation Galvanic. Several were stationed in the Marshall Islands and around the Japanese naval base at Truk in the Caroline Islands. They were to report on and attack any attempt by the Japanese Combined Fleet to react to the U.S. landings in the Gilberts. Two of these submarines, Corvina (SS-226) and Sculpin (SS-191), were lost to enemy action. Corvina was sighted on the surface near Truk by Japanese submarine I-176 and sunk by torpedoes. Sculpin was depth charged by the Japanese destroyer Yamaguma. Submarine USS Apogon (SS-308) was ordered to patrol around Moen Island and in the shipping lanes between Truk and Kwajalein. There the Americans attacked and sank the merchant ship Daido Maru. Other U.S. submarines, such as the Searaven (SS-196) were part of a wolfpack of submarines forming a defensive screen around Tarawa. Some of the American submarines had the primary role of lifeguard service, to be available to rescue airmen from downed aircraft. For the duration of Operation Galvanic, USS Paddle (SS-263) was stationed off Nauru Island, providing weather and sea condition information for the operation and keeping watch for any reaction from Nauru to the landings in the Gilberts.

The US had 10 submarines in support of Operation Galvanic. Several were stationed in the Marshall Islands and around the Japanese naval base at Truk in the Caroline Islands. They were to report on and attack any attempt by the Japanese Combined Fleet to react to the U.S. landings in the Gilberts. Two of these submarines, Corvina (SS-226) and Sculpin (SS-191), were lost to enemy action. Corvina was sighted on the surface near Truk by Japanese submarine I-176 and sunk by torpedoes. Sculpin was depth charged by the Japanese destroyer Yamaguma. Submarine USS Apogon (SS-308) was ordered to patrol around Moen Island and in the shipping lanes between Truk and Kwajalein. There the Americans attacked and sank the merchant ship Daido Maru. Other U.S. submarines, such as the Searaven (SS-196) were part of a wolfpack of submarines forming a defensive screen around Tarawa. Some of the American submarines had the primary role of lifeguard service, to be available to rescue airmen from downed aircraft. For the duration of Operation Galvanic, USS Paddle (SS-263) was stationed off Nauru Island, providing weather and sea condition information for the operation and keeping watch for any reaction from Nauru to the landings in the Gilberts.

Japan sent nine submarines to the Gilbert Islands to oppose Operation Galvanic. Their objective was to sink American warships and prevent the landing of U.S. troops on the islands. Of the nine submarines sent to the Gilberts, only three survived to return to the Marshalls. Three submarines, I-19, I-35, and I-39, were destroyed by depth charges dropped from U.S. destroyers. Three more submarines, I-21, I-38, and I-40, disappeared during Operation Galvanic and were presumed to have been sunk by U.S. depth charges or torpedoes.

Of the three submarines that returned safely to the Marshall Islands, I-169, I-174, and I-175, the last is noteworthy. Led by Lt. Comdr. Sunao Tabata, it had torpedoed and sunk the aircraft carrier USS Liscome Bay (CVE-56) while the Liscome Bay was taking part in Galvanic off Makin Island on November 24. Lost with the ship were 52 officers and 591 enlisted men.

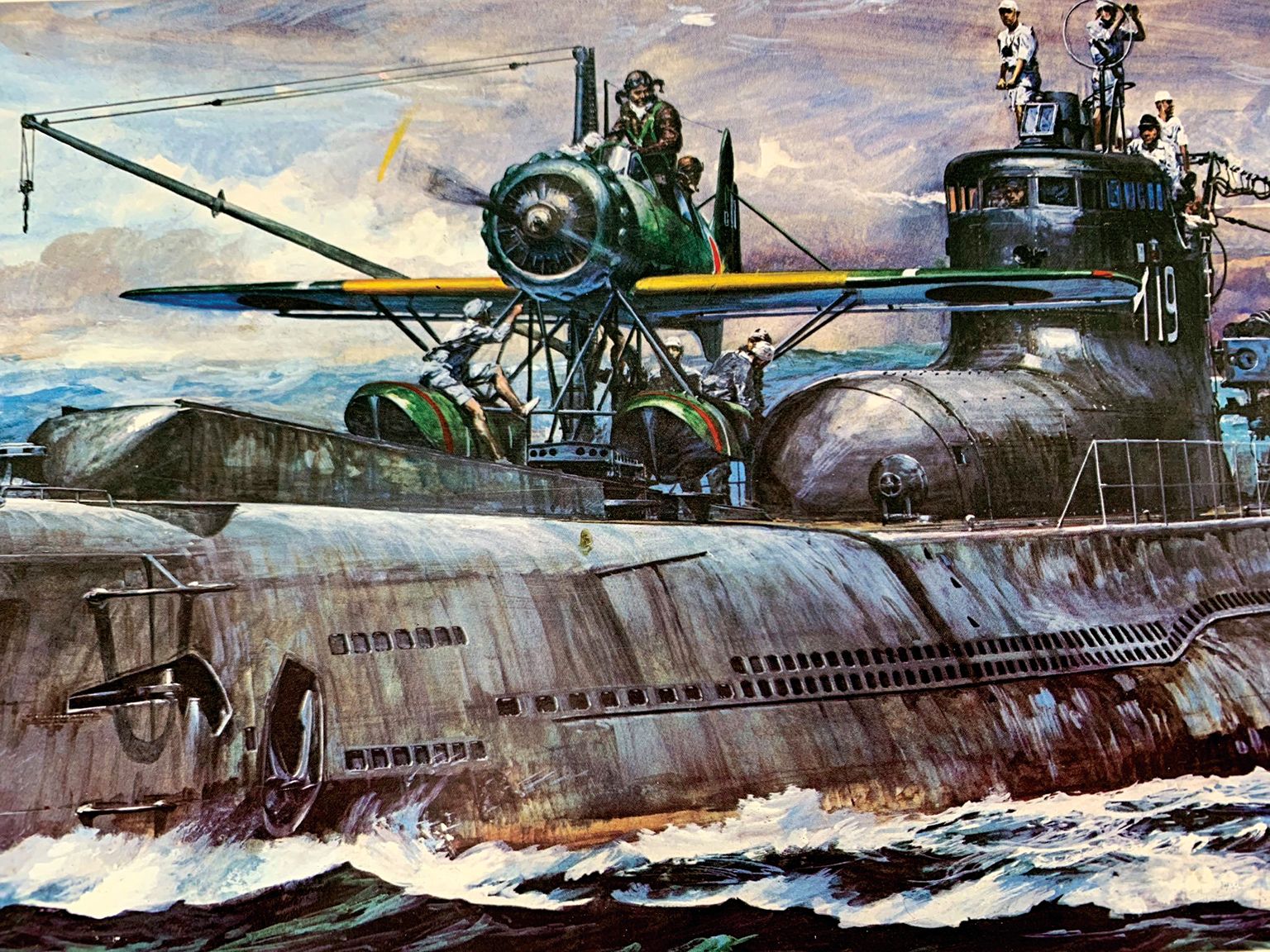

The I-35 was a 2,500 ton, 357-foot-long submarine commissioned in August 1942. Classified as a B1 submarine, a “cruiser submarine” with a range of 16,000 miles, the I-35 normally carried a small seaplane to enhance scouting capability, a Yokosuka E14Y seaplane which was launched by a catapult. A total of 20 of the B1 submarines were produced in the 1940s, starting with the I-15 which gave the class the alternative name of “I-15 Class.” The B1 submarines carried 17 torpedoes and had a crew of 94. They had a maximum diving depth of 330 feet and a maximum speed of 23 knots on the surface and eight knots underwater.

On commissioning, the I-35 was initially attached to the Kure Naval District and underwent training exercises in Japan’s Inland Sea. Here the crew gained experience in torpedo operations and in launching and recovery of the submarine’s seaplane. They also took part in joint exercises with other submarines.

In November 1942, the I-35 was assigned to the 5th Fleet for service in the Aleutian Islands campaign, where she was used to transport supplies to the Japanese garrison at Kiska. In October 1943 she had been on patrol in the area between Wake Island and Hawaii, seeking enemy ships to attack. On November 19, the I-35 was patrolling near Canton Island when Operation Galvanic commenced, and was ordered to proceed to Tarawa to attack U.S. warships there.

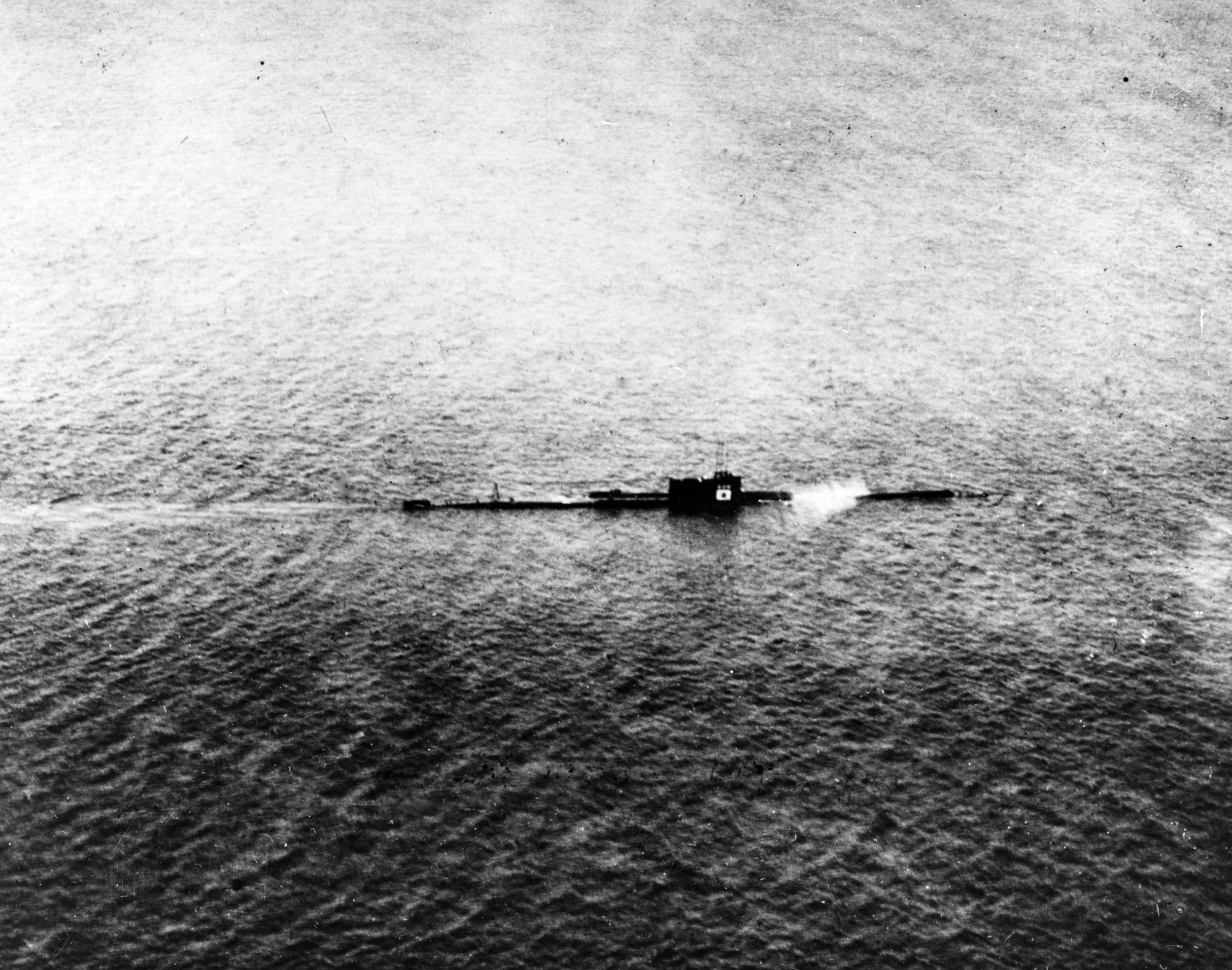

In addition to the I-35, other submarines in the Central Pacific had been ordered to Tarawa to counter the U.S. invasion. The I-19 was in near Fiji when called upon, the I-39 and the I-175 were at Truk, and the I-169 was in the vicinity of the Marshall Islands. Coming from Canton Island, the I-35 was the first of the submarines to arrive. Approaching Tarawa on November 21, the I-35 reported sighting a U.S. Navy task force consisting of aircraft carriers and destroyers southwest of Tarawa, and in the early morning of November 22, she was attacked west of Tarawa by aircraft dropping bombs and was forced to crash dive.

That same afternoon, while fighting raged on Tarawa Atoll’s islet of Betio, the I-35 was near the west coast of Betio at a depth of 65 feet. One of the submarine’s crew, Petty Officer Shingeto Ohata, has suggested that the I-35 was attempting to enter Tarawa lagoon through the western reef passage. But this seems highly unlikely. There is only one ships’ entrance into Tarawa lagoon. This is located on the southwest side of the atoll, four miles north of Betio Islet. The passage is not wide, 200 feet in places and 100 feet deep. It is not a straight run as it turns and changes direction at several places. It would have been very challenging for a submerged submarine to navigate.

During the invasion, large American warships did not attempt to enter Tarawa lagoon and run the risk of grounding. They could actually approach much closer to Betio while still in deep ocean on the western and southern sides of the atoll. Only smaller vessels such as minesweepers did enter Tarawa lagoon, and the problems that the U.S. Marines had with even the small Higgins boats and landing craft with the reefs of Tarawa are well documented. Had the I-35 even succeeded in entering the lagoon, it would have been in a maze of submerged reefs and sandbars and would likely have become stranded and trapped.

In addition to these natural obstacles, there were a number of U.S. warships in the area, many of them providing anti-submarine screening. It seems much more likely that the I-35 was only positioning herself close to the passage entrance, where American ships were entering and exiting the lagoon. The transport ship assembly area for the initial assault of Tarawa was in this area, and the rendezvous area for all boats and landing craft of the Marines amphibious landings was not far away, just inside the lagoon. The I-35 would likely have found many targets for her torpedoes in this area.

Ships of Destroyer Squadron 14, the destroyers USS Edwards, USS Frazier, USS Gansevoort, and USS Meade, were providing anti-submarine screening for U.S. ships in the vicinity of the transport assembly area. At noon, the Gansevoort was first to detect the I-35 from the sound made by her propeller, but this sound contact was soon lost and the submarine escaped.

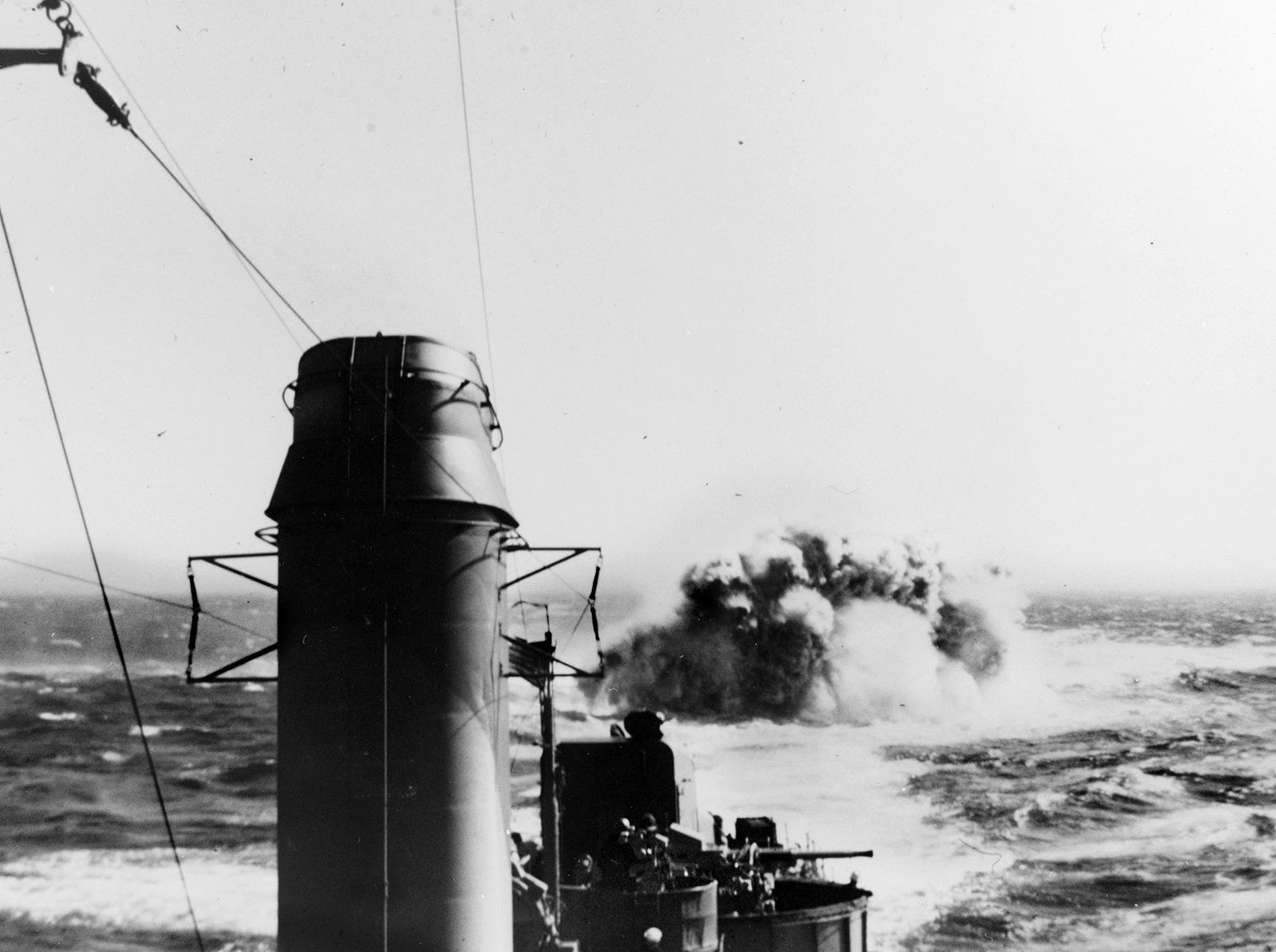

At 1500 hours, the Meade, under Lieutenant Commander John Munholland, which was also providing anti-submarine screening for U.S. warships in the transport assembly area near the entrance to Tarawa lagoon, detected an enemy submarine by sonar. Depth charges were dropped in three stages at 30-minute intervals, but without success, and sonar contact was again lost. The depth charge explosions were, however, felt on board the I-35 as she dove to 230 feet to escape the attack. The submarine was shaken but not seriously damaged.

The Meade requested assistance, and the Frazier, under Lieutenant Commander Elliot Brown, left her station as an anti-submarine screen for the battleship USS Tennessee, off the southwest tip of Betio, to assist the Meade. At 1700 hours, the Frazier picked up a strong sonar echo at a range of 2,200 yards and dropped depth charges with a medium depth setting.

At 200 yards, “Lost Contact” was reported, and another depth charge attack was made, again with a medium depth setting. At 1720 hours, the destroyers detected the submarine at a range of only 200 yards and dropped more depth charges. Soon after this, the Frazier’s executive officer reported the odor of diesel oil, and a little later an oil slick was seen on the surface of the sea. Frazier and Meade both made what would be their final depth charge drops, this time with a deep setting.

The I-35 suffered heavy damage from this depth charge attack. All the lights went out, the crew lost rudder control, and instruments and gauges were knocked out of service. Several leaks appeared, and the fuel tanks ruptured. The submarine began to fill with its fuel oil and sea water, and the captain, Lieutenant Commander Hideo Yamamoto, had no option but to blow the ballast tanks, bringing the I-35 to the surface at 1750 hours.

At the surface, the sub was trapped between the two destroyers, about a mile from each ship. Both American vessels fired at the I-35 immediately, preventing any return fire from the Japanese. All 20mm guns and machine guns on the two destroyers were brought into action, and both destroyers also shelled the enemy with their 5-inch main weapons. Four or five Japanese sailors rushed out on deck to man the submarine’s guns, one 120mm deck gun and a twin 20mm antiaircraft gun, but all were killed or wounded by machine-gun fire. Men were seen dropping as they tried to reach the gun mounted aft of the conning tower. Some of the wounded were able to retreat back inside the submarine.

The Frazier got underway heading toward the I-35 to ram her. The ship’s speed rose to 25 knots, and the bow of the Frazier struck a death blow to submarine just aft of the conning tower. The submarine’s pressure hull ruptured, causing it to rapidly fill with seawater and sink. As the destroyer backed away, the stern of the submarine began to settle down in the water and the bow rose up 20 feet into the air as she sank by the stern, nine miles west of Betio, where the ocean is about two miles deep. As the submarine went down, aircraft of an American anti-submarine patrol dropped more depth charges, which landed within 50 yards of the submarine and followed her down. At 1800 hours a loud underwater explosion was heard and felt.

Four survivors were seen swimming in the sea, and both destroyers launched boats to recover them. One of the Japanese in the water fired at his would-be rescuers, and he was shot and killed. One of the surviving Japanese was picked up by the Meade’s boat and the other two by Frazier’s. All three men had wounds from machine-gun fire, and the next day they were transferred to the transport vessel USS Monrovia for transportation to Pearl Harbor.

On Betio, very few of Tarawa’s Japanese defenders remained alive after the battle. Only 16 Japanese were captured at Tarawa, and the U.S. Marines’ roster of the 16 names includes two of the survivors of the I-35, Petty Officer Takashi Kawano and Petty Officer Ichiro Yamashita. The third I-35 survivor, Petty Officer Shingeto Ohata, has for some reason, not been included in the roster. Six of the Japanese POWs were construction workers and with the two men from the I-35, this means that only eight fighting men, Rikusentai of the Sasebo 7th Special Naval Landing Force or the 3rd Special Base Defense Force, out of a total of 2500, were captured alive.

As the Meade’s boat made its way back to its ship, it was mistaken for a submarine by a Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bomber from the escort carrier USS Suwannee, which dropped a 500-pound bomb. The bomb exploded close to the boat, lifting it up into the air, but luckily there was no serious injury to those aboard although the boat itself was badly damaged. The aircraft was driven off by gunfire from the Meade, whose gunners were not able to identify the aircraft as friend or foe. Fortunately, although the plane was hit, it was not seriously damaged and its crew was unharmed.

The Frazier had received damage in ramming the submarine. Several forward compartments were flooded, and the ship’s stem was bent concave. The lower four feet of the stem were moved approximately three feet to port from the normally straight and vertical position. Two days after the ramming, the Frazier sailed for Pearl Harbor for repairs.

The Imperial Japanese Navy was unaware that there were three survivors of the I-35, and in January 1944, it declared the I-35 presumed lost with all hands.”

Peter McQuarrie writes about World War II in the Pacific Islands. He has previously written for WWII History, Naval History, The Journal of Pacific History, Pacific Affairs and Pacific Islands Monthly. His books include: Gilbert Islands in WWII (2012) and Strategic Atolls: Tuvalu and the Second World War (1994).

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments