By Nathan N. Prefer

The U.S. Navy put many ships in harm’s way during World War II, but none more so than the Patrol Torpedo or“PT” Boats. These small, speedy, maneuverable, and extremely vulnerable craft served in all theaters of the war and compiled an admirable record during their brief wartime existence. Officially known as Motor Torpedo Boats, they would soon earn the name of “Devil Boats” from the Japanese.

The PT boat could loosely trace its origins to the First World War, when a proposal was presented to the Navy for the development of 50-foot motor torpedo boats. The U.S. Navy rejected the idea, but the Royal Navy did show some interest after the developer, W. Albert Hickman, built a prototype at his own expense. But the war ended before any contracts for development were signed. For the next 20 years the idea lay dormant, although periodically the U.S. Navy tested various examples of a motor torpedo boat with negative results.

It was not until 1938, with war looming over the horizon, that the Navy renewed its interest in the motor torpedo boat idea. In July, the Navy issued design contracts for four new boats—a 165-foot sub chaser, a 110-foot sub chaser, a 70-foot motor torpedo boat, and a 54-foot motor torpedo boat.

More than 30 designs were submitted. The winners were Higgins Industries (New Orleans, Louisiana), Sparkman and Stephens Designs (Newport, Rhode Island), Fogel Boat Yard (Miami, Florida), Huckins Yacht Corporation (Jacksonville, Florida), and Fisher Boat Works (Detroit, Michigan). Each was to produce two boats of slightly differing designs for the U.S. Navy’s evaluation.

Meanwhile, Henry R. Stephens of the Electric Launch Company (Elco) visited Britain and studied the designs of the British Navy’s motor torpedo boats. Elco purchased one of the British boats, later renamed PT-9, and brought it home to study it further. (The Germans had developed a similar craft—the Schnellboot, or “fast boat,” that the Allies called the E boat.)

After the initial trials, the Navy ordered several Elco-designed boats, but found them unsatisfactory. New competitions were held, with more trials. In the end, the Navy accepted three: Elco’s 80-footer, and two 78-foot designs from Higgins Industries and the Huckins Yacht Corporation.

A standard crew for the boats was three officers and 14 enlisted sailors, though in practice the number could vary from 12-17. This usually depended on the weapons carried by the individual PT boat. Fully loaded, the boat weighed 50 tons. The boats were made of two layers of 1-inch mahogany with a painted canvas layer between them. Copper rivets and bronze screws held the boat together. This resulted in a strong but light hull easily repaired when damaged in battle.

This was confirmed when Lieutenant (j.g.) John F. Kennedy’s PT-109 (an Elco boat) was cut in half during the Solomon Islands campaign by a Japanese destroyer; the front half of the boat remained afloat for some 12 hours before finally sinking on August 2, 1943.

A similar incident occurred when PT-323 (“Calamity Jane”—another Elco boat) was cut in half by a kamikaze off Leyte on December 10, 1944, but remained afloat for several hours. Even more incredible, in the Mediterranean, PT-308 (a Higgins boat) had her stern sheared off in a collision, yet managed to return to base for repairs. And, off Bougainville, PT-167 (Elco) was hit on November 6, 1943, by a dud torpedo that passed through the bow and failed to explode. Holed clear through, this boat was back in action the following day. Clearly, it took a lot to finish off an American PT boat.

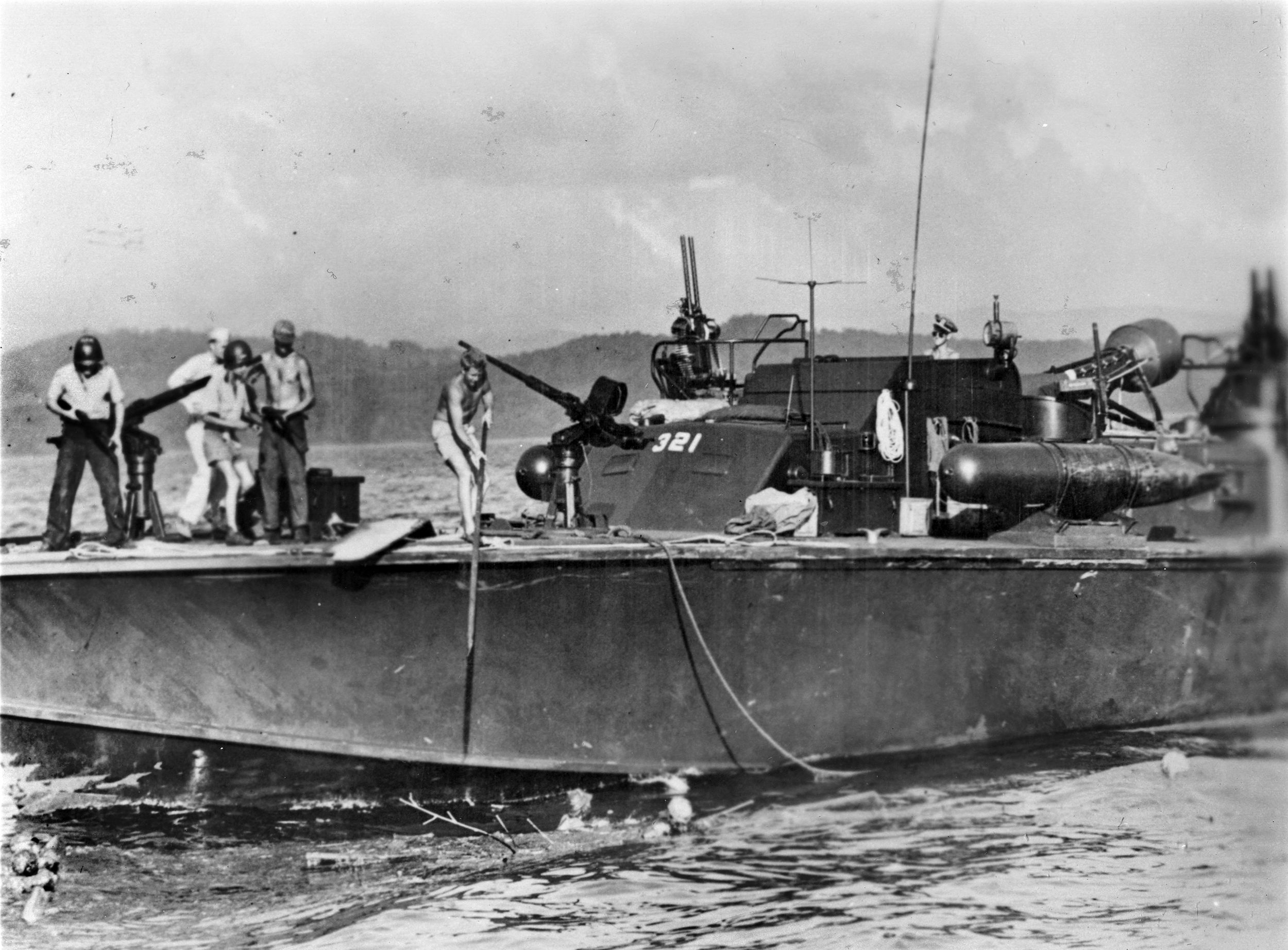

Yet survival was not the main purpose of the boats. They were there to strike at the enemy. To do this, they carried two to four Mark 8 (later Mark 13) torpedoes with a range of 16,000 yards.

Each PT boat also carried several automatic weapons—usually two or more twin M2 .50-caliber machine guns in rotating ring mounts. Many boats had 20mm Oerlikon cannons, while some carried .30-caliber Lewis machine guns on pedestal mounts. Others added .30-06-caliber Browning machine guns near the torpedo tubes also mounted on pedestal mounts. Some used 37mm cannons lashed to the forward deck. Rocket launchers and mortars also appeared on some boats.

Still others took the 37mm Oldsmobile M4 automatic cannon off of crashed P-39 Airacobra aircraft and mounted them for defense. The 40mm Bofors gun, with its 120 rounds-per-minute rate of fire was also popular. Just about anything that could shoot and fit aboard was used at some point by some boats. Only the torpedo tubes and .50-caliber machine guns could be considered standard.

Each boat was powered by three engines provided by the Navy, all derived from the Packard 3A-2500 V-12 liquid-cooled, gasoline-fueled engine, and provided a top speed of 45 knots per hour. The boats carried 3,000 gallons of fuel, enough for a standard 12-hour patrol. This decreased as the hull became fouled or the engines began to wear. Although the cockpits of the boats were armor plated, hits from enemy fire could, and did, cause catastrophic gasoline explosions, which too often resulted in the loss of a boat and her entire crew.

PT boats usually attacked at night, which covered them from enemy observation (except from aircraft, which could easily spot their phosphorescent wake in the slightest light). Only later in the war, when radar became available to them, were the odds evened. Further protection was provided by stern-mounted generators that deployed a smoke screen behind the racing boat. Like the rest of the Navy, the PT boats suffered from defective torpedoes early in the war.

For the U.S. Navy’s PT boats, the war began at Pearl Harbor. Motor Torpedo Squadron 1 was moored at the Submarine Base, Pearl Harbor. Lt. Cmdr. William C. Specht was in command while Ensign N.E. Ball was the squadron duty officer. When the first bombs exploded at Battleship Row, Ensign Ball rushed into the mess hall shouting, “We’re under attack! Man the guns!”

The sailors of MTB Squadron 1 raced to their action stations and opened fire on the swarms of Japanese planes circling overhead. Gunner’s Mate 1st Class Joy Van Zell de Jong and Torpedoman 1st Class George B. Huffman, lounging on the deck of PT-23, jumped to their machine gun and had the pleasure of seeing their torpedo-plane target fall smoking into the waters of the harbor.

MTB Squadron 1 was en route to the Philippines, and four boats had already been loaded aboard a transport. These boats also opened fire on the enemy and are credited with shooting down a second aircraft while out of the water. The PT boats were at war!

In the Philippines, 5,000 miles to the west of Hawaii, Lt. Cmdr. John D. “Buck” Bulkeley, commander of MTB Squadron 3, was jolted awake by a phone call with the news that the United States was now at war with Japan, and that Pearl Harbor had been attacked.

He immediately assembled his six-boat squadron and sailed to the tip of the Bataan Peninsula to await an attack by the Imperial Japanese Navy. Aware that he was operating before the Navy had even developed an operational doctrine for the PT boats, Bulkeley knew he was on his own.

It was here that one of the ongoing problems for the PT boats surfaced. Sailing in the darkness without lights, they came under repeated attacks by friendly forces, who mistook them for enemy vessels. This happened often throughout the war.

Bulkeley and his men were forced to watch helplessly as Japanese planes destroyed their base at Cavite and had to dodge enemy air attacks on their boats while shooting down three enemy planes.

MTB Squadron 3’s executive officer, Lieutenant Robert B. Kelly, took his section and began rescuing survivors of ships sunk in the attack. The PT boats began a system of nightly patrols, harassing the Japanese. On December 31, Bulkeley took one boat into Manila Bay and surreptitiously sank several enemy craft moored there even as the Japanese were marching into the Open City.

But this constant activity began to wear on the PT boats and crews—engines broke down but no spare parts available, gasoline was sabotaged with wax, lack of replacement torpedoes, and little to no rest for the men.

Undeterred, the PT crews continued to plague the Japanese, who at about this time gave them their nickname of “Devil Boats.” On January 18, 1942, they set off after four Japanese ships reported off Port Binanga. Taking PT-31 (Lieutenant Edward G. DeLong) and PT-34 (Ensign Barron W. Chandler) with him, Lt. Cmdr. Bulkeley entered Subic Bay, only to be detected by Japanese shore batteries and searchlights.

Racing out of sight, PT-34 returned to the area and identified an enemy cruiser. Ensign Chandler launched a torpedo attack, claiming two hits on the enemy ship and a subsequent large explosion. But aboard PT-34 one torpedo had stuck in the tube, running wildly, and was in danger of destroying the boat itself. Using toilet paper stuffed into the propeller of the torpedo to stop its mechanism, PT-34 was able to make its way home. Not so PT-31.

Lieutenant DeLong’s boat had been sabotaged by soluble wax placed into the gas tanks. The engines stopped and the boat drifted aground. Ordering his crew to abandon ship, Lieutenant DeLong remained aboard to scuttle the boat before the nearby Japanese could capture it intact. After several close calls ashore avoiding the Japanese, DeLong and his surviving crew were rescued by loyal Filipinos, but three crew members were lost.

MTB Squadron 3 was down to four boats after another ran aground. These kinds of firefights would continue over the next three months, slowly whittling away the fighting strength of MTB Squadron 3.

It was while searching for survivors of PT-31 that Bulkeley’s men would begin fighting an opponent they would face throughout the war: a Japanese military barge. These barges were of various sizes and powered by engines not unlike the PT boats themselves. They were armed, some were armored and, when carrying infantry, could make use of their weapons as well.

Not worth a torpedo, in the American estimation, they were usually attacked with machine guns and other weapons carried aboard the PT boat. Once subdued, PT sailors would board them, if still afloat, and recover prisoners and intelligence information, which often proved quite valuable. In this first instance, for example, a wounded Japanese captain and captured documents provided the information that would lead to the next PT triumph.

On February 1, 1942, Lt. Cmdr. Bulkeley’s MTB Squadron 3 acted on the intelligence gathered in the fight with an enemy barge. The Japanese had, unknown to the Americans, been landing troops behind their lines on Bataan, on a nightly basis. The idea was to build up a strong force to attack the American lines from the rear. The Army commanders asked for Navy help.

Together with a few remaining Army fighter planes, MTB Squadron 3 intercepted this operation and sank several barges loaded with troops headed for the enemy enclave.

Times were hectic and confused, and some of the successes claimed by MTB Squadron 3 were mistaken, but the PT reputation continued to increase. As one noted historian wrote about the fight off Bataan, “The PTs did not accomplish much else in this campaign and on every occasion claimed more damage than subsequent investigation substantiates. Of the two cruisers and two large merchant ships that they claimed, none were actually sunk or even damaged.”

But if any episode made the reputation of the PT boats, it was their “rescue” of General Douglas MacArthur. Ordered to evacuate to Australia to continue the fight, MacArthur had few options for transportation. Only the Navy had a way—either by submarine or by PT boat to Mindanao, where Army bombers would take his party (his wife, son, and other members of his staff) the rest of the way; MacArthur chose the PT boats. The news came as a shock to MTB Squadron 3, which had been planning their own escape to the China Coast.

Bulkeley selected his four boat captains. In addition to Lieutenant Kelly, Ensigns Anthony Akers, and George Cox, and Lieutenant Vincent S. Schumacher would captain the PT boats. Their instructions were to stay together, but if any boat broke down it was to be left to its own resources. The Japanese were to be avoided at all costs, but if attacked, Lieutenant Kelly and three boats were to attack the pursuers while Bulkeley in PT-41 with General MacArthur’s party was to try and escape. Navy officers on Corregidor were giving five-to-one odds that the escape would fail.

It was a good bet. None of the boats had navigational devices, so navigation was by guess and by God. Each boat carried extra gasoline in steel drums on deck, a recipe for disaster should so much as one bullet strike the drums.

PT boat engines were supposed to be overhauled every few hundred hours, but those of MTB Squadron 3 had been running for months without an overhaul; there were no spare parts. Rust in the engines had reduced speed to about half of what it was supposed to be in a clean engine. Nevertheless, MTB Squadron 3 loaded Macarthur’s party aboard PT-41 and set off for Mindanao, followed by PT-32, PT-34, and PT-35.

Lieutenant Kelly’s PT-34 was the first to run into trouble. It slowly began to fall behind because of fouled engines. In the middle of the night the engines finally quit and the boat began to drift. In accordance with orders, the others pushed on. PT-34’s crew began frantically cleaning the engines and soon had them running again. But by now dawn was beginning to break over the Philippines, so Kelly headed for a cove in the Cuyo Islands to shelter for the day.

Lieutenant Schumacher‘s PT-32 also ran into trouble. A Japanese destroyer began pursuing him, and to increase speed, the steel drums loaded with essential gasoline were rolled overboard. To further lighten the load and discourage pursuit, torpedoes were fired at the destroyer, which soon became identified as PT-41! The morning mist had nearly caused a “friendly fire” incident between PT boats.

Bulkeley, along with Schumacher and Kelly soon rendezvoused at the Cuyo Islands, where the crews worked tirelessly on their engines. Ensign Akers’ PT-35 would never arrive. It had broken down and the crew and passengers had to make their own way to Mindanao.

After several close calls with real Japanese destroyers, the group reached their destination, after 35 hours and 580 miles navigating enemy-controlled waters. The first legend of the PT boat had been born. For this and other actions, Bulkeley received the Medal of Honor.

While Lieutenant Commander William Specht was in Melville, Rhode Island, creating “Specht Tech,” to turn out highly trained PT boat skippers, the U.S. Marines were landing on the Solomons. Soon this campaign involved the bulk of the American and Japanese navies.

One feature of this ongoing naval battle was the “Tokyo Express”—a naval supply and reinforcement route which the Imperial Japanese Navy employed almost every night. To stop this flow of enemy troops and supplies, a new MTB Squadron 3 was sent to the island of Tulagi. These new and improved boats were crewed by fresh officers and men eager to prove that they were the equal of their predecessors.

They got their chance the night of October 14, when the commander, Lt. Cmdr. Alan Montgomery, ordered them out to intercept a Japanese bombardment of Guadalcanal. Riding in Lieutenant John M. Searles’s PT-60, Montgomery led his boat into battle for the first time. Torpedo hits on two Japanese cruisers were claimed.

Night after night the boats went out and usually found the enemy in the infamous “Iron Bottom Sound.” Soon a pattern emerged. Two boats would go ahead, acting as scouts for the others. They would give warning of an approaching Tokyo Express convoy to the main body, which would then deploy for a surprise attack.

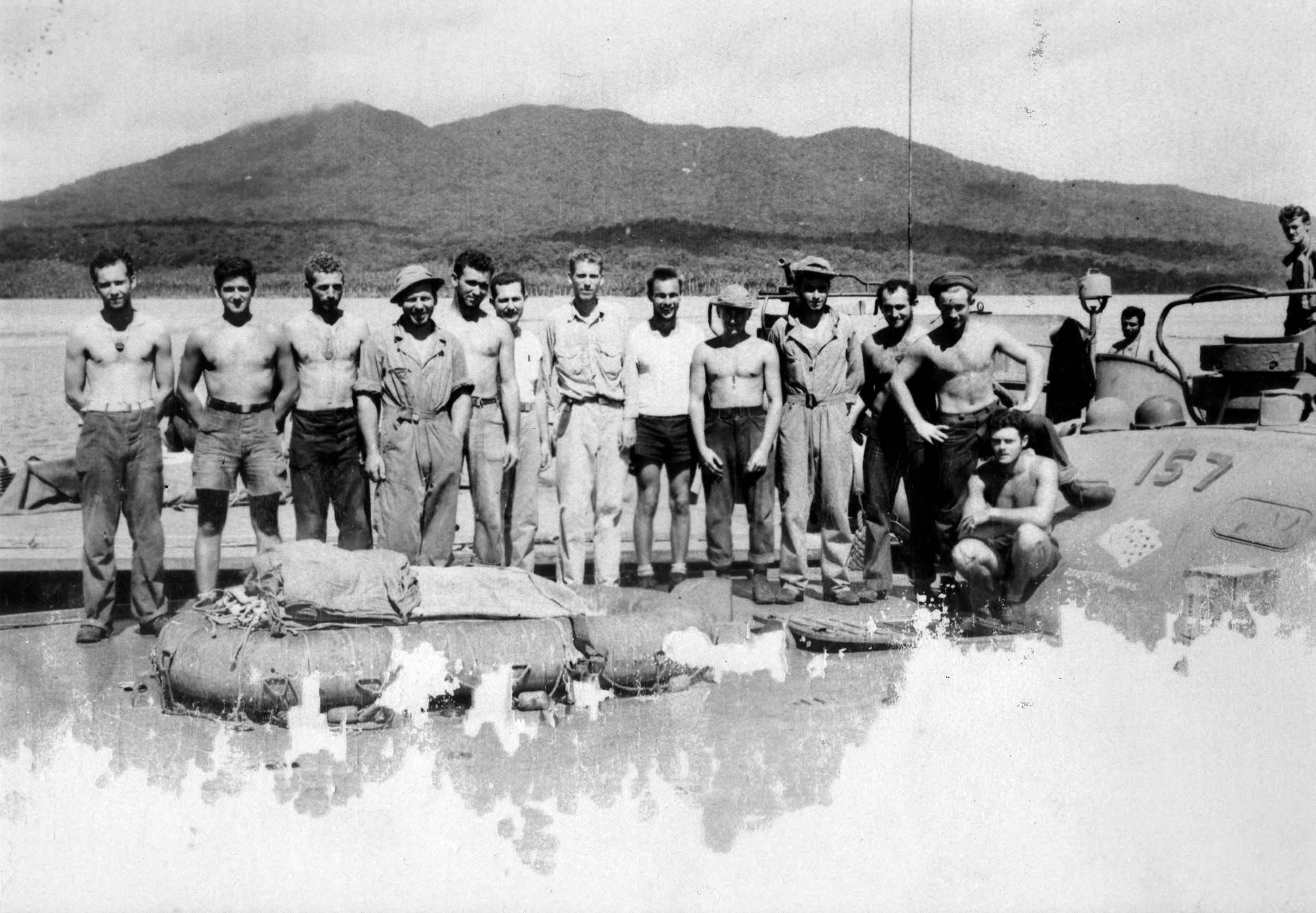

The seamen, average age 19 or 20, quickly adapted to the needs of the Guadalcanal Campaign. In the hot, torrid climate of the Solomons, the young PT crews soon learned that the uniform of the day was either no shirt, or a tattered one, khaki pants torn off at the knee, and scuffed shoes with toes cut off to allow air to enter.

Successes began to accumulate. On December 11, 1942, Lieutenants Lester H. Gamble, Henry S. “Stilly” Taylor, and William E. Kreiner combined to sink the enemy destroyer, IJN Teruzuki. To the south, off the New Guinea coast, MTB Division 17 probed the many inlets in search of the enemy.

On Christmas Eve, Ensign Robert F. Lynch in PT-122 was doing just that when he spotted the dark outline of a surfaced submarine. Attacking without hesitation, two torpedoes produced one large explosion. But the enemy vessel was still afloat. Another run launched two more torpedoes and another explosion. The IJN’s submarine I-22 was no more.

It was not all one-sided, of course. Against the coast of Guadalcanal, Japanese destroyers caught Lieutenant Jack Searles’s PT-59, Lieutenant Bart Connolly’s PT-115, and Ensign J. J. Kelly’s PT-37. The Americans’ only chance was to break through the surrounding enemy.

PT-115 charged one destroyer, fired two torpedoes, and saw the enemy ship begin to list. Shells and torpedoes filled the night, star shells lit the dark sky, and the PTs continued their fight. Connolly managed to find a protective rain squall and race to safety.

So, too, did Jack Searles. Ensign Kelly had fired his four torpedoes when a blinding flash engulfed his PT-37. A shell had hit the gas tanks and the boat swiftly disintegrated, the crew finding themselves in the dark waters of Iron Bottom Sound. Badly wounded Motor Machinist Mate 1st Class Eldon C. Jenter spent the next three or more hours trying to stay afloat while sharks swam nearby. He was the only survivor of PT-37.

Nearby, Ensign R.L. Richards’ PT-123 was engaging an enemy destroyer when a Japanese float plane, unseen and unheard, glided in and dropped a bomb on PT-123’s fantail. The boat swiftly became a blazing wreck and the crew forced into the water. Enemy fighter planes, guided by the flames of PT-123, strafed the men swimming in the water. Four men disappeared beneath the waves. Three others were wounded by machine guns.

Even after the fall of Guadalcanal, the Tokyo Express kept running to Japanese-held islands in the northern Solomons. Again, the PT boats were called upon to stop this flow.

On August 1, a report that five Japanese destroyers were making an “Express” run through Blackett Strait sent 15 PT boats, including that of Lieutenant John “Jack” F. Kennedy’s PT-109, to the area. The group divided to cover more ground, and Lieutenant Henry “Hank” Brantingham in PT-159 led five boats to an attack on what he believed to be barges hugging the coastline.

The boats soon discovered that the barges were in fact Japanese destroyers. Brantingham’s PT-159 and Lieutenant William F. Liebenow’s PT-157 attacked with torpedoes and reported one hit on an enemy destroyer. The ensuing fight erupted into a crescendo of noise and flashing lights.

But, to the north, Lieutenant Kennedy saw none of this and continued his patrol in company with Lieutenant John R. Lowry in PT-162 and Lieutenant Philip A. Porter, Jr., in PT-169. None had seen or heard any enemy vessels in the vicinity. But at about 2:30 in the morning, suddenly the IJN Amagiri loomed out of the darkness and sliced PT-109 in half.

The Japanese destroyer, equally unaware of the American’s presence, sailed away. Two of Kennedy’s men died with the boat, while the others, many wounded or burned by gasoline fires, were left floating in the water. The epic story of their survival and Lieutenant Kennedy’s gallantry would be yet another legend of the PT boats. (See Sidebar)

Along the New Guinea coast, the main enemy of the PT boats continued to be enemy barges. The Japanese were now plating them with armor and arming them heavily in anticipation of conflict with the American patrol boats, which they now called “Green Dragons.”

The PT boat skippers were finding that when they attacked now their bullets would bounce off the barges’ armored sides while they faced gunfire from guns as large as 40mm. Further, the Japanese were placing coast-defense guns and heavy machine guns along the coast where their barges usually sailed.

But the Americans were improving their weapons as well. New boats—faster, more maneuverable, and more heavily armed—were appearing in the combat zones. These carried torpedo racks rather than the more cumbersome tubes, had radar aboard, and were now guided by electronic gyro-stabilized compasses, making navigation much easier and more accurate.

Lieutenant Commander John Harllee, a veteran of the Pearl Harbor attack, came out to New Guinea with his Squadron 12 in early 1943. Hidden a mile up the Morobe River to avoid detection from the air, the squadron began operations on September 21, when Ensign Rumsey “Rum” Ewing and his PT-191 (“Bambi”) were sent out on the first night mission.

Ensign Ewing remembered his instructors’ words at Melville, “Going into battle, there are two kinds of men who are not afraid—liars and bigger liars.” Sailing along the coast on a dark night, “Bambi” spotted a small cargo ship dead ahead. Attacking with guns, Bambi soon set the enemy ship ablaze.

But word quickly came that enemy float planes were about, and, to avoid air attack, Ensign Ewing wanted to finish off the enemy ship quickly. An attack by depth charges was decided upon—the PT boat would race up to the side of the enemy ship and roll a 400-lb. depth charge off the stern, to explode under the enemy vessel.

But the stubborn Japanese vessel refused to sink. Ewing ordered a second attack, followed by Ensign Robert R. “Red” Read’s PT-133. Calling “Closer,” “Closer,” the two PT boat skippers renewed their attack. This time the charges exploded almost aboard the cargo ship, and it quickly disappeared beneath the waves. This method of attack with depth charges soon became known as the “bowling ball attack.”

Ewing and Bambi were also involved in another episode in New Guinea some weeks later. Patrolling quietly along the coast, Bambi and Lieutenant Robert Lynch’s PT-68 came upon two enemy barges sailing along the darkened coast. The boats attacked as the barges raced for the safety of the nearest beach. Bambi scored first and was followed by PT-68.

Ewing turned away successfully, but when Lynch turned, he suddenly ran aground. Calling for help, Lynch soon discovered that, while firing on the barges, the PT boats had overshot into the nearby jungle, which was now on fire. It quickly became apparent that the PT boats gunfire had not only hit the barges, but a Japanese installation hidden in the jungle ashore.

Even as PT-191 tried to pull PT-68 off the reef, Japanese soldiers ashore began to fire upon both boats. Fighting an urge to run, Bambi continued to try and pull her sister boat off the reef, to no avail. Then enemy shore batteries opened fire on the boats. Enemy soldiers ashore armed with rifles began wading out towards the American boats. Clearly, it was time to go.

PT-68 was abandoned, her crew climbing onto PT-191. Once away from shore, the they fired at PT-68, which burst into flame, and the Japanese who retreated back into the jungle.

With the crew of PT-68 aboard and relishing the massive fires that now swept the newly discovered Japanese base ashore, Bambi made it safely back to base.

Secret enemy bases seemed to draw the PT boat crews. One such base had been discovered a few miles inland along the Pulie River in eastern New Britain. Far inland, covered by jungle and on a barely navigable stream, it was considered secure from enemy attack. But not from the PT boats.

Lieutenant Oliver J. “Ollie” Schneiders was anxious to take a crack at the base. Taking a Japanese interpreter with him, he sailed his boat under a starless night using his radar to move up the river. Sailing into ideal ambush territory, the Americans held their breath, expecting at any moment to be ambushed by Japanese guns on either side of the stream.

But nothing happened, and soon huts and a small wharf appeared out of the darkness; Lieutenant Schneiders had arrived at the hidden enemy barge terminal. The Japanese interpreter shouted out, “Where can we tie our barge?” but received no response.

But then a voice answered, and lights flashed on, revealing a large enemy base with huts, warehouses, and sheds all hidden under thick jungle cover. Instantly, Lieutenant Schneiders shouted “Fire!” and the PT crew blasted the base with every weapon aboard. Fires broke out everywhere. Scores of the enemy ran out of the huts directly into the Americans automatic-weapons fire. Ammunition dumps began exploding. Surviving Japanese ran off into the jungle.

Lieutenant Schneiders now ceased fire. Half his mission was complete; the enemy base was destroyed. But there remained another, equally important half: his escape. Every Japanese for miles around was now alerted to the presence of an American “devil boat,” and would be trying to destroy it. The boat turned around and began a slow return to the ocean.

But it had not gone far when it became stuck on the muddy bottom of the Pulie River. Stranded, and exposed by the fires still raging at the enemy base, Lieutenant Schneiders’ crew used the engines to free the boat. Soon they were on their way again. Without a shot being fired against it, the boat and crew made it safely back to their own wharf at Morobe.

By July 30, 1944, General MacArthur’s New Guinea Campaign was ending. The western tip of the island had been reached, and tens of thousands of Japanese lay stranded behind the advancing Americans. But the PT boats were still in the fight.

One of their assignments was to prevent the 37,000 Japanese on Halmahera from escaping to the nearby island of Morotai. This they managed to do, keeping them bottled up until the end of the war, allowing the invasion of Morotai to proceed without interference from the large enemy force on Halmahera.

It was during the invasion of Morotai that Ensign Harold A. Thompson’s aircraft was shot down by enemy fire. He landed in Wasile Bay, badly wounded. A Catalina flying boat dropped him a raft, into which he climbed. But the raft began to drift towards the enemy-held shore. Soon he was at an enemy cargo ship barely 150 yards from shore.

To avoid drifting ashore, Ensign Thompson tied his raft to the Japanese ship, which was unmanned. A Catalina tried to rescue Thompson but was driven off by enemy fire from coast artillery and nearby machine guns. The downed pilot was now being used as bait for further rescue attempts. He was in a narrow channel blocked by a minefield and protected by shore batteries. His only hope was rescue before darkness set in, when the Japanese would come for him.

Thompson’s plight came to the attention of Admiral Daniel “Uncle Dan” Barbey, the commander of the Morotai operation. He summoned Commander Selman “Biff” Bowling, commander of Seventh Fleet PT boats, along with his intelligence officer and two of his squadron commanders. They were asked to give a rescue mission a try.

Commander Bowling did not want to order any of his men on what they all understood was a suicide mission, but both squadron commanders were willing, if not eager. The choice fell on Lieutenant Arthur Murray Preston’s Squadron 33. Lieutenant Preston was a 31-year-old graduate of Yale University and Virginia University’s Law School. Faced with the most difficult mission of his Navy career, he called for volunteers from Squadron 33. Every officer and man volunteered.

Preston selected Lieutenants Wilfred B. Tatro’s PT-489 (“Eight Ball”) and Hershel F. Boyd’s PT-363. Bowling reluctantly allowed the squadron intelligence officer, Lieutenant Donald Seaman, to accompany the mission.

With Preston sailing in “Eight Ball,” they raced south to the area of the rescue. Meanwhile Lieutenant Robert Stanley studied maps of Wasile Bay in preparation for the rescue. Not only was Lieutenant Thompson close to the enemy beach, but there was an active enemy airbase on a nearby island!

The boats arrived at the entrance to Wasile Bay only to find that their promised naval air cover had failed to arrive. With darkness fast approaching, Lieutenant Preston gave the order to enter the bay. Immediately, several enemy shore batteries opened fire on the zig-zagging boats. Faced with accurate enemy fire, Preston gave the order to retreat, which led the boats through an enemy minefield. Fortunately, neither hit a mine.

Once the two boats had left the bay, the promised air support arrived. Lieutenant Preston again ordered his boats into the bay under the air cover. Lieutenant Tatro opened full throttle on his three engines and raced into Wasile Bay as the air cover bombed and strafed the coast-defense guns. But the Japanese continued to fire on the two PT boats, which maneuvered wildly to avoid that fire.

Twenty minutes passed while the boats reached the entrance to the bay once again. Here the noise level rose to fever pitch, as explosions, tracers, and shouting voices filled the air around the bay. Every gun on the two boats fired back, few seeing targets but feeling better while fighting back.

Lieutenant Preston’s Medal of Honor citation reads, in part, “Lt. Cmdr. (then Lieutenant) Preston led PT-489 and PT-363 through 60 miles of restricted, heavily mined waters. Twice turned back while running the gauntlet of fire from powerful coastal defense guns guarding the 11-mile strait at the entrance to the bay, he was again turned back by furious fire in the immediate area of the downed airman.

“Aided by an aircraft smokescreen, he finally succeeded in reaching his objective and, under vicious fire delivered at 150-yard range, took the pilot aboard and cleared the area, sinking a small hostile cargo vessel with 40-mm fire during retirement.

“Increasingly vulnerable when covering aircraft were forced to leave because of insufficient fuel, Lt. Cmdr. Preston raced PT boats 489 and 363 at high speed for 20 minutes through shell-splashed waters and across minefields to safety. Under continuous fire for 2½ hours, Lt. Cmdr. Preston successfully achieved a mission considered suicidal in its tremendous hazards and brought his boats through without personnel casualties and with but superficial damage from shrapnel. His exceptional daring and great personal valor enhance the finest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.” Lieutenant Preston’s Medal of Honor was the second, and last, awarded to PT boat sailors in World War II.

In a rare occurrence, PT boats also took part in the largest fleet action of the war. During the multi-faceted Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, the PT boats were assigned to defend Surigao Strait in the Philippines. Some 35 boats of Squadron 7 (Lt. Cmdr. Robert Leeson) and Squadron 12 (Lieutenant Weston C. Pullen, Jr.) were ordered to station themselves in advance of the battleships, cruisers, and destroyers of the U.S. Seventh Fleet at the end of Surigao Strait. Their orders were specific: they were not to engage the Japanese until they had reported their composition, course, and speed.

Near midnight of October 24, Ensign Peter R. Gadd in PT-131 (“Tarfu”) looked at his radar screen and was shocked to see an increasing number of large targets begin to appear. Together with Lieutenants Joseph A. Eddin’s PT-152 (“Lack-A-Nookie”) and Ian D. Malcolm’s PT-130 (“New Guinea Crud”) the skippers soon identified two battleships, two cruisers, and destroyers.

Repeated attempts to notify Seventh Fleet of the sighting failed to elicit a response. But the Japanese had spotted the “Green Dragons” and opened fire on the boats with heavy naval guns. Lieutenant Malcolm’s PT-130 took a direct hit from an 8-inch shell that failed to explode but damaged the boat. Aboard PT-152 an enemy shell blew the 37mm gun off the forecastle, killing the gunner and starting fires aboard.

To escape, gunners fired at the Japanese searchlights, which were soon extinguished. The battered boats soon joined with Ensign Dudley J. Johnson’s PT-127; Johnson was finally able to contact Seventh Fleet. The “Devil Boats” had done their job.

In the Philippines, the boats came up against their deadliest enemy: the kamikaze. Inexperienced Japanese suicide pilots often mistook the boats for larger U.S. Navy ships and crash-dived on them, thinking they were hitting destroyers or even cruisers.

In mid-December 1944, Lieutenant Byron F. Kent and his PT-230 (“Sea Cobra”) were cruising off Mindoro when three enemy planes were spotted approaching. Immediately the boat went to full speed and began zigzagging. The first plane was fast approaching, and Lieutenant Kent had to choose: turn left, or turn right. The wrong call would mean the lives of 15 Americans and loss of PT-230. He turned right at the last possible moment, and the first kamikaze fatally plunged into the sea.

The second plane came in hard on the heels of the first and again Lieutenant Kent had to choose. This time he turned left, and the kamikaze slammed into the ocean less than 45 feet from Kent’s boat. The third plane came screaming down with guns blazing. Another last-second turn and the last Japanese plane went into the water so close that the boat’s stern was lifted out of the water and the crew splashed with flame, smoke, debris, and water. But there were no injuries, and PT-230 was still afloat.

At the end of the war, the United States Navy decided that it would be too expensive and too time-consuming to retain the PT boats in a mothball fleet. The decision was made to beach them and, after stripping them of all useful materials, to burn 121 of them on the beach of Samar Island in the Philippines.

During the war, 531 PT boats were built. Of these, 99 were lost during the war. Accidents and friendly fire accounted for 32, while 27 were scuttled to avoid capture, eight had been rammed by enemy ships, two destroyed by kamikazes, nine by enemy mines, six by coast-defense guns, three by strafing, and seven by enemy naval guns.

Several boats survived the war and post-war destruction. Thirteen are known to have survived and are still afloat. PT-48 (Elco), a South Pacific veteran, is being restored in Kingston, New York. PT-305 (Higgins), a Mediterranean veteran, is fully restored at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

Another Mediterranean veteran, PT-309 (Higgins) is also fully restored at the Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas. Two boats, PT-617 (Elco) and PT-796 (Higgins), are on display at Battleship Cove Naval Museum at Fall River, Massachusetts.

Most of the other survivors have been converted to pleasure boats, dinner cruise boats, sightseeing boats, and fishing boats. Recent research indicates that Lieutenant Kennedy’s second boat, PT-59, may be under the Harlem River in New York City.

At least 330 officers and crewmen of the PT boats lost their lives during the war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments