By James Bilder

There are important similarities between Hitler’s final great push into Belgium and Luxembourg and Mussolini’s drive south of Garfagnana. To conduct their operations, both dictators had to scrape together the last remnants of effective fighting men and equipment, both had to wait for inclement weather to conceal their troops’ movements from the Allied warplanes that ruled the skies, and both faced incredibly long odds.

But the similarities largely end there. The world watched breathlessly as the fighting in the Ardennes played itself out. The Germans, after some five weeks of bitter fighting, were finally beaten and largely driven back.

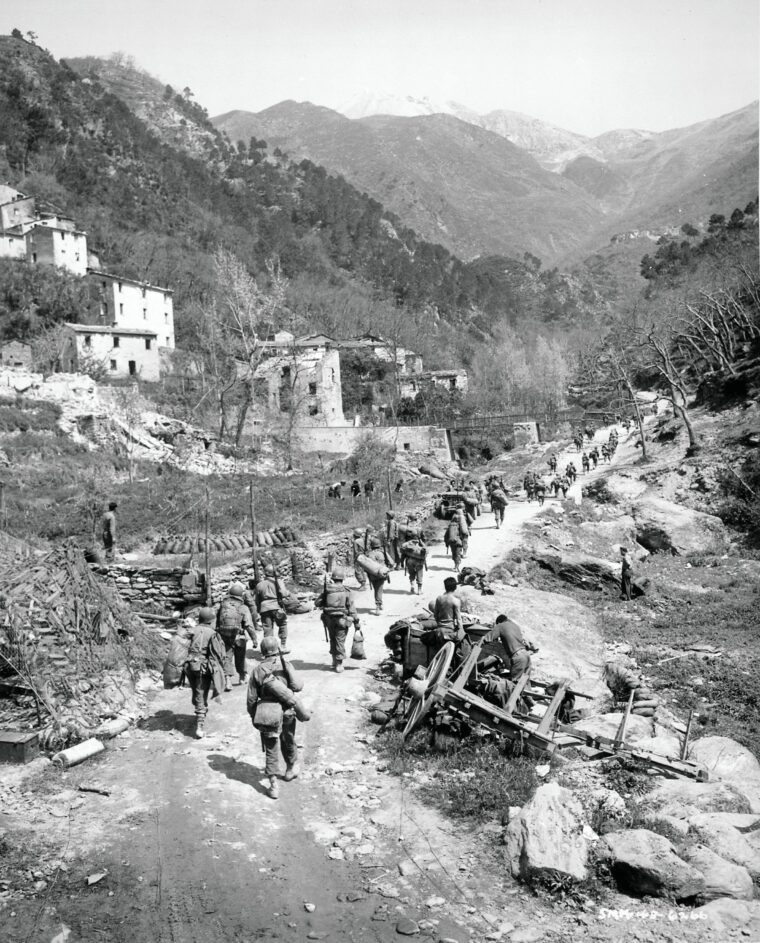

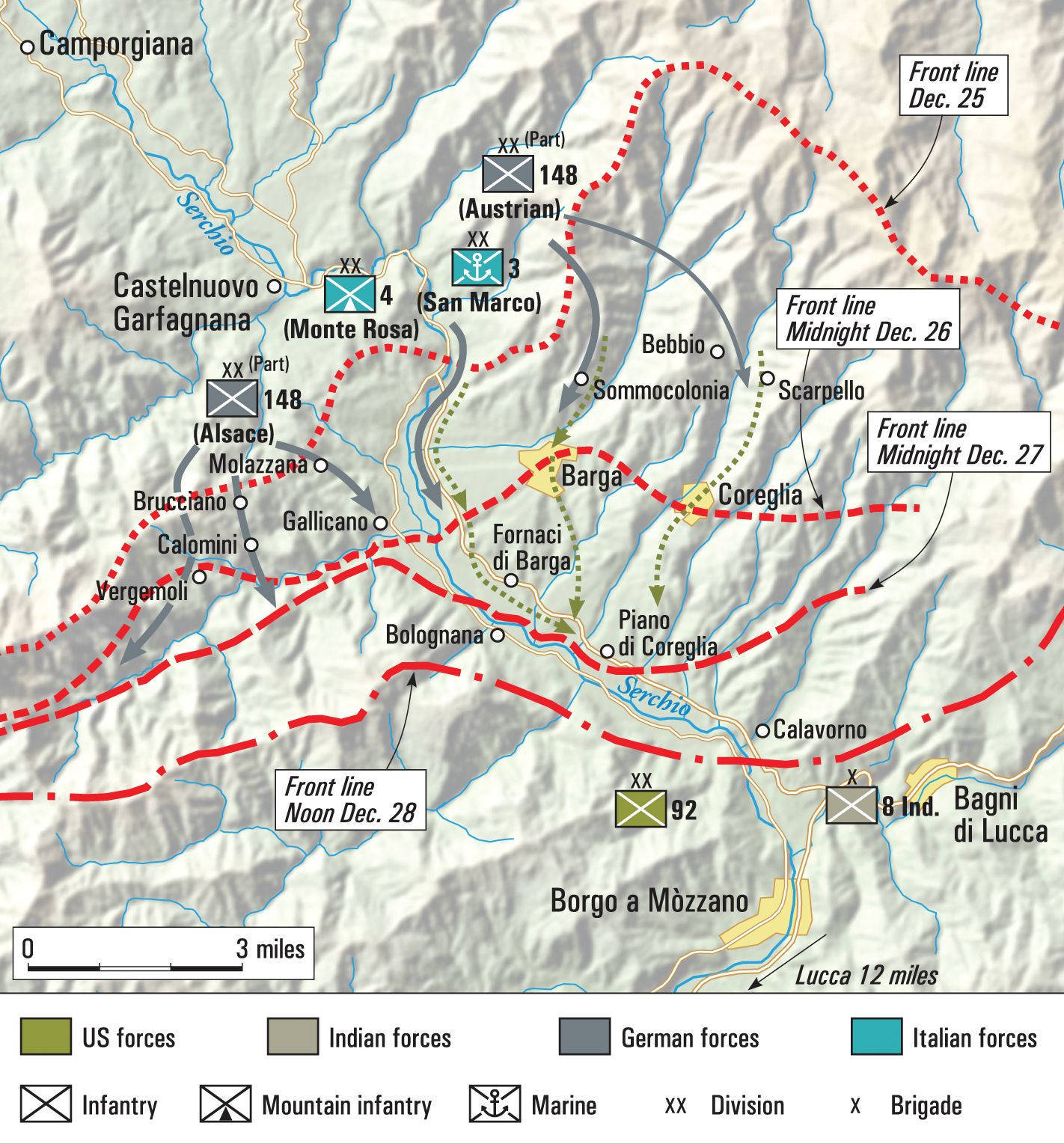

Scant notice was paid to the near-simultaneous fighting in northwest Italy, where from December 26-31, 1944, an Italian force supported by Austrian mountain troops hit the Americans head-on along the western edge of the Gothic Line in the Serchio Valley and sent the GIs reeling back 25 kilometers to the south.

Unlike the Germans at the Bulge, the victorious Axis forces at Garfagnana not only secured their positions along their main defensive line but were able to hold onto them until the latter part of April in 1945.

Known to the Italians as the “Christmas Offensive” (Offensive di Natale) and to the Germans as “Operation Winter Storm” (Unternehmen Wintergewitter), the roots of the Battle of Garfagnana go back to Hitler’s rescue of Mussolini from captivity in September 1943 and the setting up of a puppet state in northern Italy.

The first half of 1943 had been disastrous for Mussolini and the Italian military. In February, what was left of the battered Italian troops fighting in the Soviet Union had to be withdrawn lest they be annihilated. By the end of May, the Anglo-American forces in North Africa had captured any Italians left stranded there, and by mid-July the Americans and British were advancing across Sicily.

The Italian people had reached their limit. The Italian Grand Council of Fascism approved a vote of “no confidence” against Il Duce around 2 a.m. on July 25, 1943. The vote of the council was 19-8 against the dictator. Mussolini’s son-in-law, Count Galeazzo Ciano, voted with the majority, an action for which he would pay with his life when Mussolini had him shot “for treason” the following January.

At first, Mussolini thought the vote meant nothing and went ahead with a scheduled meeting with King Victor Emmanuel III that same day. Following the meeting, the King had Mussolini taken into custody.

Mussolini was comfortably confined in an exclusive resort (Hotel Campo Imperatore) on the Gran Sasso massif in the Apennine Mountains when, on September 12, 1943, he was unceremoniously rescued (possibly even contrary to his desires) by German paratroopers and whisked away to Austria. Within three days, Mussolini was meeting with Hitler in the Wolf’s Lair in East Prussia.

There he heard Hitler’s plan for a new Fascist Italian State propped up by the German forces stationed there. Mussolini supposedly hesitated, preferring instead to go into retirement. Hitler is claimed to have then threatened to destroy a number of Italian cities and their inhabitants, thus forcing Mussolini to graciously reconsider the offer.

On September 23, 1943, the formation of the Italian Social Republic (RSI) was proclaimed with Benito Mussolini designated, once again, as its leader. Mussolini held the dual titles of prime minister and chief of state, but he and the RSI were both a complete farce, nothing more than puppets under Hitler’s control.

Rome was designated the titular capital of the RSI, but Mussolini did not dare go there—though Allied air attacks were a genuine concern, the greater threat would probably have been from his own citizens.

Instead, Mussolini was in a virtual state of house arrest in the Province of Brescia, in the de facto capital of Salo, in northern Italy. For that reason, the Italian Social Republic is often referred to as the Republic of Salo.

The fate of the Axis forces in Italy did not improve with any of these events. The day before Mussolini’s rescue by the Germans, Italy had changed sides, and Italian citizens, with the support of many Italian military and partisans, were in full revolt against the Germans and any Italian military loyal to fascism.

The German/Italian Axis continued to lose its grip over Italy throughout 1943 and 1944. Despite the highly competent leadership of German Field Marshal “Smiling Albert” Kesselring and the spirited resistance of the Axis troops under his command, the Allies continued to claw their way slowly northward up the Italian peninsula.

Allied forces battling in Italy had to endure staggering casualties among their ranks, but still they managed, one by one, to break through the formidable defensive lines that were always quickly established by the retreating Axis forces whenever they were forced to give up ground.

Rome, declared an open city, fell to the Allies in June 1944—just two days before the Allied landings at Normandy. The outlook could hardly have been dimmer for Hitler and Mussolini; still, both dictators and their armies were determined to fight to the last.

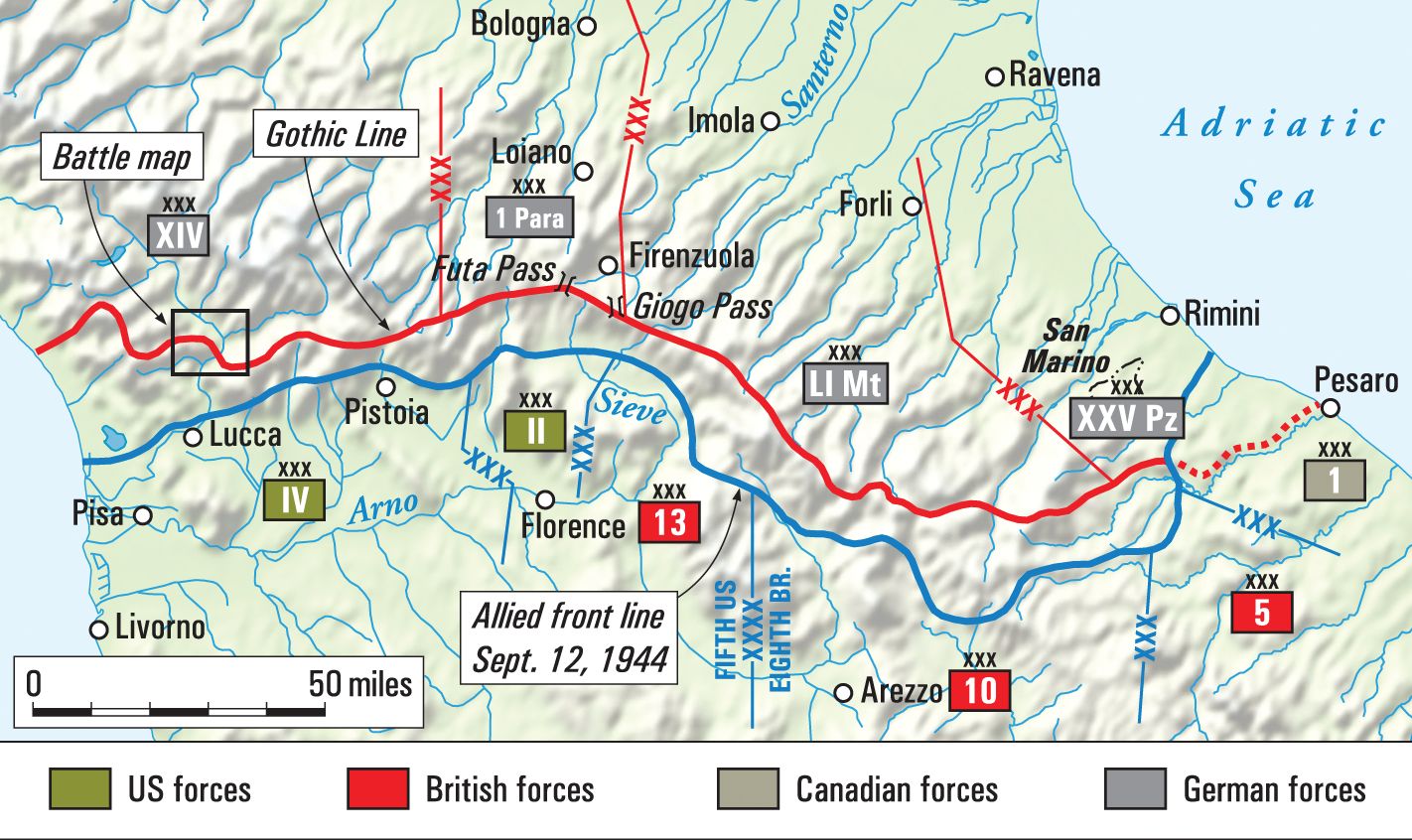

As August 1944 drew to a close, the noose was tightening on all sides. On the Western Front, nearly all of France had been liberated, and Patton had almost reached the German border. To the east, the Red Army was at the gates of Warsaw, and, to the south, German and Italian troops of the RSI were dug in along the Gothic Line (renamed the “Green” Line by the Germans in June 1944) defending the northern section of Italy that was still under Mussolini’s control.

After the capture of Rome, the fighting in France took precedence over that in Italy, so the Allied high command had started to siphon off troops from Italy and send them to France. On the Italian front, this clearly reduced the combat effectiveness of Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s Fifth U.S. Army (on the western flank of Italy) as well as that of Lt. Gen. Richard McCreery’s Eighth British Army (in the east of Italy). Still, the Allies pressed on with an offensive against the Gothic Line (Operation Olive) that began on August 25, 1944.

Here the Allies would encounter an Axis defensive line that was seemingly impregnable. The Gothic Line stretched from roughly La Spezia on the west coast, across the Apennine Mountains, all the way to Ravenna on the east coast. It held almost 500 artillery emplacements and just under 2,400 machine-gun nests. These were all connected by an elaborate trench system that was, in turn, protected by a jungle of barbed wire, numerous tank ditches, countless concrete bunkers, and a steep, stony terrain that was almost impossible for civilians to traverse in peacetime.

The Allies knew the Axis defenders would fight ferociously, and they did. Yet the American and British forces pressed forward and seemed to be within reach of breaking the Gothic Line. The lynchpin was Bologna, near center of the line. It appeared for a while that a two-pronged attack there, carefully coordinated between the Anglo-American armies, might succeed in breaking the enemy’s defenses.

Hopes rose on October 20, 1944, when the “Blue Devils” of the U.S. 88th Infantry Division captured Monte Grande, but that was as far as the U.S. Fifth Army could effectively go. Heavy casualties and the transfer of troops to France meant no reiforcement and, by October 28, the American drive simply ran out of steam.

The British fared only slightly better. The Eighth Army got as far as Faenza on December 17 before they, too, had to stop for the same reasons.

Winter weather, mountainous terrain, strong enemy defenses, and difficult logistics meant the Allies would have to wait for spring before continuing their assault on the Gothic Line. This is what Mussolini and his German overseers had been waiting and hoping for—a chance to strike back over the Christmas truce with a surprise counterattack.

Mussolini and his minister of defense, Field Marshal Rodolpho Graziani, had been pressing Kesselring for an offensive since early October. Graziani was a dedicated fascist and the only Marshal to remain loyal to Mussolini after he was deposed. Graziani believed in an Italian empire and had demonstrated his determination and ruthlessness in places like Libya and Ethiopia.

Mussolini wanted an offensive for obvious reasons. Like Hitler, he had delusions that the Axis could still win the war. By attacking southward, Mussolini hoped the Allied forces might be pushed out of Italy, or, short of that, enough room could be secured for the production and deployment of German “wonder weapons.” If nothing else, it could buy him more time to keep his neck upright on his shoulders.

Axis generals were far more pragmatic. They had known, since the height of Operation Olive’s drive in October, that they had to do something to take the pressure off Bologna. A successful drive south against either the British or Americans could accomplish that, while simultaneously boosting Axis morale and lowering that of the Allies.

There was also a chance to capture much-needed supplies such as weapons, ammunition, food, medicine, communications equipment, and even fue. Finally, a successful push south would allow for the lines to be reconsolidated in a way even more favorable to the Axis defenders.

A series of fatal or near-fatal events among military leaders on both sides shifted commands in Italy. First, on the Axis side, Field Marshal Kesselring was severely injured on October 23, 1944, when his staff car, driving at night under blackout conditions, ran into an artillery piece being towed along a narrow mountain road in the midst of a military traffic jam. It would be more than three months before he could return to duty.

The changes for the Allies began on December 15, 1944, with the death, from natural causes, of Field Marshal Sir John Dill in Washington, D.C. Dill was the Chief of the British Military Mission in Washington. Dill’s replacement was General Henry Wilson, the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Mediterranean. Wilson’s position was filled by General (now Field Marshal) Harold Alexander, who had been commanding the 15th Army Group in Italy.

The elevations in command then affected the Americans, as General Mark Clark was promoted from commanding the U.S. Fifth Army to command of the 15th Army Group. Finally, command of Clark’s Fifth Army went to General Lucian Truscott.

Truscott was an amazing soldier and commander. He had enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War I and falsified his academic record, claiming that he had completed a year of college when in reality he had not even finished high school. He secured a spot in the officer’s candidate school at Fort Logan Roots and was commissioned a second lieutenant and stationed along the Mexican border throughout the war.

Truscott was a “mustang”—a soldier who works his way up through the ranks without the benefit of graduating from a military academy. He performed admirably as commander of the 3rd Infantry Division during the invasion of Sicily and the fighting in Italy. He was given command of VI Corps in February 1944 during the Battle of Anzio; 14 months later he was promoted to command of the U.S. Fifth Army.

The Germans, too, had a new army commander, opposing the Americans on the west side of the Apennine Mountains. He was a man whose daring and luck, along with an ability to cheat death, were almost as impressive as his name. He was General Kurt Oskar Heinrich Ludwig Wilhelm von Tippelskirch, and on December 13, 1944, he assumed command of the German 14th Army, positioned on the north side of the Gothic Line directly across from Truscott’s Fifth Army.

Unlike Truscott, Tippelskirch began his military career as an officer. He joined the German army cadet corps in 1910; when war broke out four years later, he was captured by the French in the first Battle of the Marne; the French held him for six years.

Tippelskirch held staff positions between the wars and, after Hitler’s invasion of the U.S.S.R., took command of the 30th Infantry Division outside Leningrad as part of Army Group North. Tippelskirch distinguished himself at the Pola River when his division successfully blunted and then battered a Russian corps as it was about to breach the German lines. He was awarded the Knight’s Cross for his actions.

When his division was among those encircled in the Demyansk Pocket during the winter of 1942, he was prepared to stay and fight until he was ordered to be flown out. He returned to Russia to fight at Stalingrad as the German liaison to the Italian Eighth Army. He went on to both a Corps and Army command in Russia, but nothing could slow the Red Army’s advance.

When the German forces were encircled at Minsk, his Fourth Army had been skillfully repositioned as far east as he could dare move it. That did not allow it to avoid encirclement, however, and eventual destruction, but Tippelskirch was fortunate enough to be in Germany at the time. Even there, he had a near-fatal air crash in July 1944. He was awarded an oak cluster to his Knight’s Cross at month’s end.

As the new commander of 14th Army, Tippelskirch had to make the decision as to where the joint Italian/German offensive would strike. It was not a difficult analysis for him to make. On the other side of the Gothic line, in a quiet sector, was the U.S. 92nd Infantry Division.

The U.S. Army was still racially segregated during World War II, and the 92nd Division was made up of mostly African-American troops. The 92nd had adopted the motto “Buffalo Soldiers” in 1917. It was a moniker that had been given to the black troopers of the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments during the Plains Wars by the Native Americans they fought. It was a respectful reference to the toughness the black troopers displayed in battle.

The 92nd was the only black infantry unit of the United States to fight in Europe, and their record is debated even today. They are generally regarded as having been poorly trained, poorly led, poorly regarded, and (not surprisingly) poorly performing.

They arrived in Italy in August of 1944 and participated in the Operation Olive Offensive. They did not demonstrate a high degree of aggressiveness, and their gains, while modest, were often quickly lost in counterattack.

Back in October, Mussolini and Graziani had hoped for a massive push involving 40,000 troops, massive armor, and air power; but Tippelskirch had limited time and few resources with which to mount a significant offensive. His force would consist of infantry equipped with small arms and some machine guns. There also would be some artillery units to provide support. There were no tanks or planes available, which made little difference since there was also no fuel available.

There were enough troops to form three columns for an attack: one German and two Italian divisions.

The first column would consist of German troops from the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 285th Regiment of the 148th Infantry Division. These troops were mainly French “volunteers” from Alsace; most had been in the ranks since 1940. They were not highly regarded and were expected to show limited aggressiveness on the battlefield. Desertion rates were so high among this unit that Italian mountain troops had to be dispensed on November 26 and 27 to keep the remainder of the regiment in the ranks at gunpoint.

The second column would be made up of Italian troops. The majority would come from the 4th “Monte Rosa” (Alpine) Division. The units included were the 3rd Battalion of the 1st Regiment, the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Regiment, and the 23rd Reconnaissance Unit.

The Monte Rosa Division consisted of volunteers from the north of Italy, loyal fascist Italians who had made their way north at the time of the Italian armistice, as well as some Italian POWs being held by the Germans. The Monte Rosa Division was trained in Germany and sent to Italy in July 1944. Their original mission had been to prepare coastal defenses against American amphibious landings, but they had spent most of their time fighting partisans. By December, the division’s original strength of 20,000 troops had been reduced by roughly half due to casualties and desertions.

The rest of the Italian troops came from the 3rd “San Marco” (Marine) Division—specifically, the 2nd Battalion of its 6th Regiment. This division was made up of formal naval personnel along with volunteers from northern Italy. Like the Monte Rosa, the San Marco had been trained in Germany, sent back to Italy to prepare coastal defenses, and ended up having their primary mission converted to fighting partisans.

Also, like Monte Rosa, the San Marco Division was also plagued by low morale and desertions. Still, it should be noted that the remaining troops of these Italian units had fought well and remained in the ranks because of their devotion to the cause.

The third and final column was made up primarily of Austrians. It consisted of the 4th Battalion (Mountain Troops) of the 148th Infantry Division, the “Mittenwald” (Mountain) Battalion, also from the 148th Infantry Division, and finally, the Kesselring Machine-Gun Battalion of the 148th Division. Like the Monte Rosa Division, the Germans’ 148th Division was also understrength.

The Austrians were an elite group, highly trained and well experienced. Like the Italians participating in this offensive, they could be counted on to fight. The combined force in these three columns totaled some 9,100 men (about two-thirds of whom were Italian). The Axis force was about half the total number of Americans in the 92nd Infantry Division facing them on the other side of the Gothic Line.

The artillery supporting the Axis Christmas Offensive totaled around 100 pieces and came from the 51st Artillery Regiment (Motorized) and the 1048th Artillery Regiment. It consisted of a single 155mm battery, three 105mm batteries, two 75mm batteries, an 88mm anti-aircraft group, and mortars.

Overall command of the Axis attack would go to German General Otto Fretter Pico, the commander of the 148th (Reserve) Division. He was a career officer who’d fought in the First World War, and in the Second he’d held combat commands in Poland, France, and Russia. His list of decorations was extensive, including the Knight’s Cross.

Tactical field command would go to Italian General Mario Carloni, the commander of the Monte Rosa Division. Carloni, too, fought in both world wars. His service in World War II included Greece and Russia, where he had a son killed in action in 1942. After the Italian armistice, he was briefly held by the Germans but was freed when he expressed his desire to join Mussolini’s RSI army. It was Carloni who advocated strongly for a major offensive as early as October 20, 1944, when he met with Lt. General Walter Jost, who commanded the 42nd Jäger (Light Infantry) Division.

The Axis commanders decided to take advantage of the Christmas truce and jump off shortly after midnight on December 26. Their primary objective was to drive the Americans back as far as possible and perhaps even retake Lucca and the strategic port at Livorno. Their plans were not a complete secret to Allied commanders; German messages encoded through Ultra and sent back and forth to Italy were intercepted by the Allies and revealed enough for Clark and Truscott to know that something was coming their way.

The area held by the 92nd Division was a somewhat obvious target, as the division was inexperienced and had not shown a very aggressive spirit when on the offensive. Truscott immediately transferred the 2nd Brigade of the 8th Indian Division, along with the 337th and 339th Regiments from the U.S. 85th Infantry Division, to IV Corps to bolster the area. His timing could not have been more opportune.

The 92nd Division was commanded by Major General Edward Almond. Almond was a native of Virginia and had graduated from the Virginia Military Institute prior to the United States’ entry into WWI. He had fought at the Argonne in 1918, where he was wounded, and also awarded a Citation Star (these were converted to Silver Star medals by Act of Congress in 1932).

Almond taught military science at the Marion Military Institute in Alabama and infantry tactics at Fort Benning, where he became friends with George C. Marshall, the Army Chief of Staff and a fellow VMI alumnus.

Almond received additional training at both the Army and Navy War Colleges, worked in military intelligence, and seemed well prepared for a significant combat command. Because of Marshall, Almond moved from brigadier to lieutenant general ahead of many of his peers. He was given command of the 92nd Infantry Division as soon as it was activated on October 15, 1942, and held that command until war’s end.

Almond made no secret of his beliefs that black soldiers were inherently inferior to their white counterparts. He did not appear to believe that the 92nd would be a highly effective infantry division, and his attitudes and command decisions seemed to play no small role in making his beliefs something of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

As the day of battle approached, Almond had 18,000 men, mobile guns, and armor holding a six-mile line that started in the Serchio River Valley and extended westward to the Ligurian Sea.

The Axis could not conceal their troop movements from Italian partisans and Allied air reconnaissance, so they had been sending out false messages that an attack in the Serchio Valley was set for December 10. Almond responded with extensive field works that included minefields and trenches complete with barbed wire.

When the date came and went without an attack, Almond issued an order that would prove to be both contrary and confusing. The 92nd Division, along with the rest of IV Corps, was already preparing to launch their own offensive on Christmas Day. Almond ordered his division to be on alert and patrol in anticipation of an enemy attack. Division officers weren’t certain whether their mission was to prepare for offense or defense.

Meanwhile, the Axis geared up for their offensive. Defense Minister Graziani and General Carloni paid a visit to the troops of the Monte Rosa Division, who would be expected to do the lion’s share of the fighting. The German offensive in the Ardennes was well underway, and thus the awaited offensive in Italy was not long in coming.

On Christmas Eve, word came down to the 92nd Division that the Allied offensive for Christmas was canceled. The directive was to prepare for an enemy attack expected on December 27.

A sigh of relief must have gone through the ranks—the men could enjoy Christmas Day and even have the day after to prepare their defenses. Unfortunately for the men of the 92nd Division, Allied intelligence had missed the mark by 24 hours and it would cost them.

The Axis did not want to forewarn the Americans of an attack by opening with an artillery bombardment, so at 3 a.m. on December 26, the code word to initiate the attack, “Gustav” was issued. The Austrians of the German left flank (3rd Column) moved up quietly out of the fog and darkness, and by 4:50 a.m. began their assault against Sommocolonia on the east side of the Serchio River.

The area was garrisoned by elements of Fox Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 366th Regiment along with some Italian partisans. Axis officers commented after the battle that while the 92nd may not have demonstrated much determination on offense, they were very tenacious on defense. The fighting lasted most of the day and was only resolved when the Austrians finally called for artillery support. Only 18 Americans were able to successfully withdraw; the rest of their outfit was now either KIA or POW.

There was no love lost between Axis troops and partisans of any type, but on this occasion the tactics of the partisans (mostly communists) were equal to Nazi standards. The partisans were using the civilians at Sommocolonia as human shields; once, when an Austrian fired through a door at a partisan, the bullet took the life of a four-year-old child.

The “Mittenwald” Machine-Gun Battalion (around 200 strong) moved further south and quickly seized the villages of Carpelo and Bebbio from the 92nd Recon Troop, which retreated to the south. The Austrians pressed on and began to assault the strategic garrison at Barga, which was being defended by the 2nd Battalion of the 366th Regiment, at about 2 p.m.

The defenders would fight all through that day but, as night approached, they fell back in disarray, leaving a 500-yard gap that the enemy used to seize Barga and then Coreglia to the southeast. The Austrians had made some small diversionary attacks to their west earlier in the day, but the Americans quickly recognized these as a ruse since the Germans quickly fell back whenever challenged there.

This was as far as the Austrian troops needed to advance in order to secure the Axis left flank, and that would allow the Italians in the center to make the main thrust of the attack.

By dawn of the 26th, there was no element of surprise left to be had, so the Italian sector in the center and the Alsatian sector on the right opened up on the American defenders south of Castelnuovo di Garfagnana with an artillery barrage consisting primarily of mortars while the Monte Rosa Division had heavy artillery support, as well.

The Alsatians encountered only light resistance and, under the watchful eyes of Italian supervision, quickly took Fornaci; but the Italians cursed the Alsatians for their obvious failure to seize and press the initiative against the poorly organized American defenders.

The center of the attack proved to be the most difficult for the Axis. The Americans were falling back, but their withdrawal was more organized and costlier to the attackers. By nightfall, the Italians were in Galicano and Molazanna, but they were repulsed with heavy losses at Brucciano, which they assaulted with troops from their regimental headquarters.

The Italians were far from beaten, though, and went on to occupy Calomini, which then put the Americans of the 370th Regiment, defending Vergemoli, in danger of being encircled.

Vergemoli had a minefield as its forward defense, and American artillery was raining down fire on the Italians as they tried to cross it. In addition, the American defenders and some partisans were putting up a stubborn defense despite being hit by enemy artillery. In the end, the Americans finally had to slip out, leaving the partisans to cover their withdrawal.

Vergemoli fell to the determined Italians, but the victory was somewhat pyrrhic, the losses in men simply could not be replaced. The attackers had penetrated roughly 10 kilometers behind the American lines across a front that was almost 25 kilometers wide, but there were more advances yet to come.

On the morning of December 27, the Italians pressed forward and took Bolognana while the Germans had patrols on the outskirts of Calavorno, where the Americans were reported to be in full retreat. The Austrians took Fornaci di Barga without a fight, as it had already been abandoned by the retreating Americans, and then secured Piano di Coreglia, which was the last of their designated objectives.

Small Axis units continued to move south all the way to Bagni di Lucca. Axis scouts at the most forward positions again reported that the Americans were in full retreat. Even so, this was as far as the Axis offensive could proceed.

Like the Allies before them, the Axis simply ran out of steam. There were simply no more men—no reserves with which to press forward, and no reinforcements with which to hold on to captured ground.

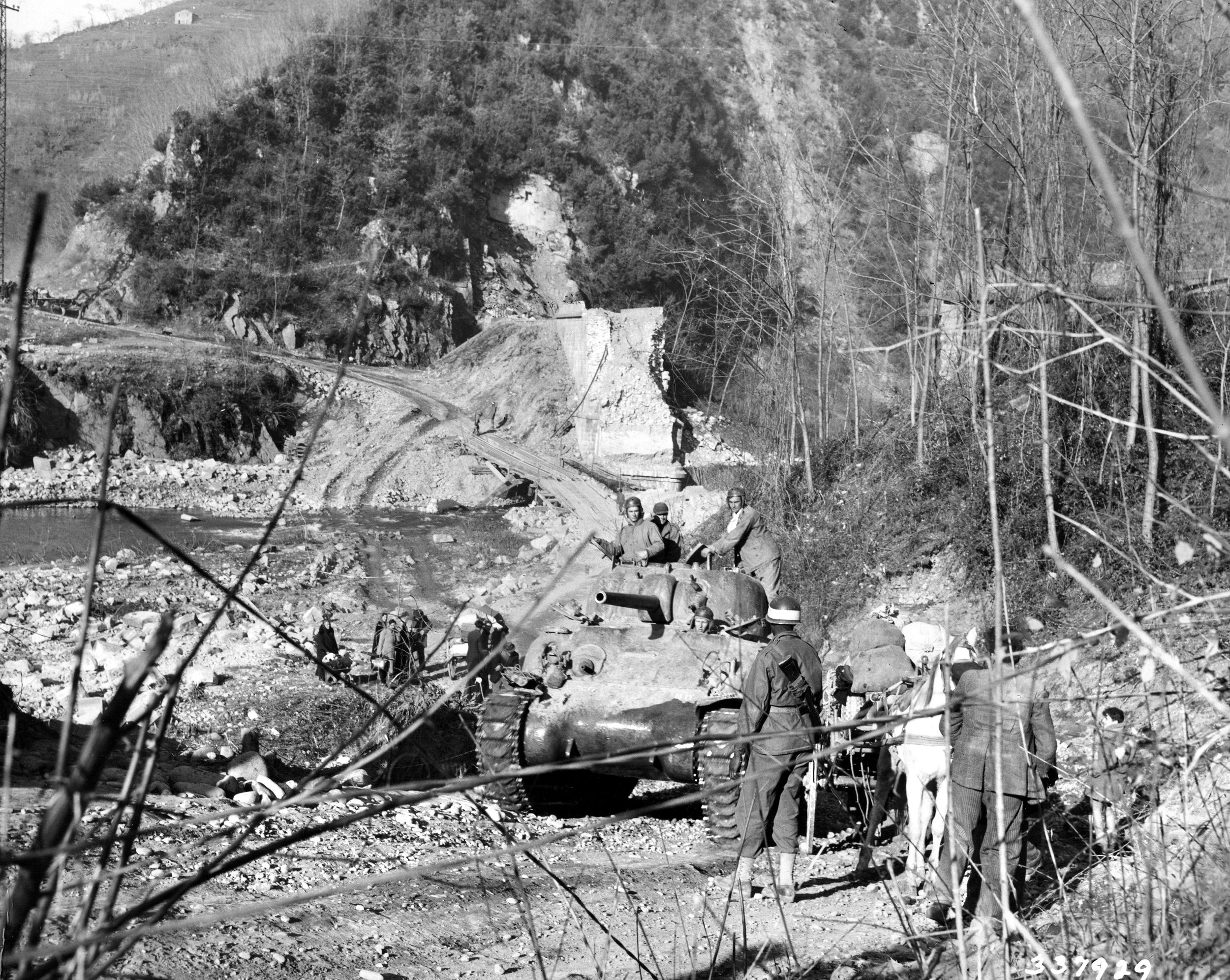

The attackers would be facing fresh troops from the U.S. 1st Armored Division, the 34th and 85th Infantry Divisions, and the 8th Indian Infantry Division of the British Army. If that weren’t enough, the skies had cleared and P-47s fighter-bombers from the XXII Tactical Air Command could now attack Axis forces at will.

Over 4,000 sorties were flown by a variety of Allied planes. The bombing was so extensive that civilian casualties ran high, and even an Axis hospital at Camporgiano, which was caring for the wounded of both sides, was hit.

On the night of December 28, General Fretter Pico was forced to give the order to fall back. It was an organized withdrawal; although skirmishes took place all along the lines, the Allies—under the command of the Eighth Indian Division—failed to press their pursuit of the retreating enemy.

There was a noteworthy clash at the Sergio River between the retreating troops of the San Marco Division and those of the pursuing Eighth Indian Division. The Indian troops were not as well trained or experienced as their Italian counterparts and were forced to disengage after the Italians knocked out two of their tanks. By New Year’s Eve, the Axis forces were essentially back to where they had started.

Allied figures for the battle put the number of KIA and POWs at around 1,000 men for each side. Italian historians claim their casualty rates were only half that number.

The desires of Mussolini and Graziani to continue the attack were as deluded as Hitler’s after the Battle of the Bulge; unlike the Ardennes, though, the Christmas Offensive in Italy did not hasten the eventual defeat of the Axis forces there, but probably extended their survival time.

The offense had accomplished all of the tactical and strategic objectives that Generals Tippelskirch, Fretter Pico, and Carloni had set forth. The attacking Axis forces secured all of their designated objectives, routed an American infantry division (essentially destroying much of its effectiveness as an attacking force), and raised morale among the Axis forces in Italy while simultaneously lowering Allied morale.

The Axis troops also canptured much-needed ammunition, medicine, food, and communications equipment. The Gothic Line was re-consolidated—some two kilometers forward in some places—and held until late April 1945 due in no small measure to the forces that the Allies had to divert from Bologna. The Gothic Line was still intact even after the Russians had surrounded Berlin.

General Almond is rightly regarded as having behaved shamelessly. Despite his initial inaction, his inability to organize either an effective defense or fighting withdrawal, and his failure at the appropriate time to lead a counterattack, he lay the blame entirely on his troops.

He maintained that their performance had “cost” him a promotion to a higher command—this despite the fighting resolve shown by his own men at Sommocolonia, Barga, and Vergemoli. Almond asserted that black troops were inferior to whites despite historical accomplishments of black units ranging from the 54th Massachusetts of the U.S. Civil War, to the “Harlem Hellfighters” of World War I, and the Tuskegee Airmen, just to name a few.

The success of the Christmas Offensive only delayed the inevitable for Mussolini and his Italian Social Republic. He and his mistress were captured and executed by communist partisans on April 25, 1945, as they attempted to escape to Switzerland. The Axis forces in Italy were surrendered to the Allies by General Kesselring on April 28, 1945—closing a theater that had seen some of the worst fighting of the war.

Almond was a corps commander early in the Korean War, didn’t do that well. Got third and last star early 1951, rotated back to the States in July 51, retired in 1953, passed away in 1979.