By Mason B. Webb

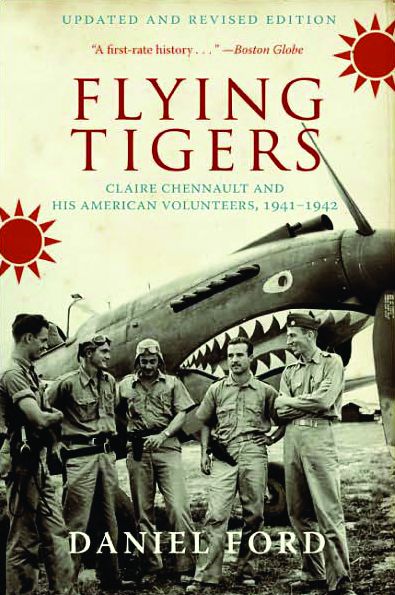

During the dark, early days of World War II, when the Imperial Japanese army, navy, and air force were running roughshod over Asia and the Pacific, it seemed that nothing could stop them. Only a small band of American mercenary fliers based in Burma and known as the Flying Tigers, led by a leather-faced fighter named Claire Chennault, seemed able to challenge and defeat the Japanese.

For a fabulous salary of $600 a month (the equivalent today of $144,000 a year), plus a $500 bounty for every enemy plane they shot down, the cocky, swaggering men (most of whom resigned their commissions in the Navy and Air Corps to sign up) who flew the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighter aircraft with the fearsome shark face painted on the nose tangled with Japan’s Imperial Wild Eagles in the skies above China and Burma and won immortality.

For a fabulous salary of $600 a month (the equivalent today of $144,000 a year), plus a $500 bounty for every enemy plane they shot down, the cocky, swaggering men (most of whom resigned their commissions in the Navy and Air Corps to sign up) who flew the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighter aircraft with the fearsome shark face painted on the nose tangled with Japan’s Imperial Wild Eagles in the skies above China and Burma and won immortality.

The exciting story of this legendary fighting force that wore American uniforms but Chinese insignia is told in Daniel Ford’s Flying Tigers: Claire Chennault and His American Volunteers, 1941-1942 (Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C., 2007, 368 pp., photographs, maps, index, bibliography, softcover, $15.95), the definitive history of the legendary Flying Tigers. Every page contains a new tidbit of information and rich, long-forgotten detail.

Most importantly, Ford’s prose—and the use of dozens of first-person accounts by the pilots who made up the AVG (American Volunteer Group, known variously among themselves as the Panda Bears, Adam & Eves, and Hell’s Angels)—puts human faces and flesh on a unit that everyone has heard of, but about which very few people know.

For example, one of the pilots was hard-drinking Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, who would later, as a Marine pilot, win the Medal of Honor in aerial combat. Among many other unforgettable characters are Jim Howard, Tom Cole, Charlie Bond, Moose Moss, Sandy Sandell, and Bob Neale who, with remarkable candor, confessed to his diary that he was scared to death on missions. “I can remember times where I’d be sick to my stomach before combat, just from nervous tension,” he wrote.

Another flyer, Charlie Bond, recalled that he and Bob Neale once pounced on a single Japanese fighter who showed remarkable bravery and skill, even charging Bond head on. Bond said, “Bob and I fought that little devil some five to ten minutes. He must have known he was done for, but he was a game little guy.”

The book is so full of stories of derring-do and close calls that it seems like fiction—a tall tale of brash young men in a bygone era—yet it is all true.

As one of the news reports quoted in the book said, “Last week ten Japanese bombers came winging their carefree way up into Yunnan, heading directly for Kunming, the terminus of the Burma Road. Thirty miles south of Kunming, the Flying Tigers swooped, let the Japanese have it. Of the ten bombers … four plummeted to earth in flames. The rest turned tail and fled. Tiger casualties: none.”

Anyone who loves stories of aviation combat and wants to learn more about the underreported war along the China-Burma border will love Flying Tigers. A riveting read.

The Pentagon: The Untold Story of the Wartime Race to Build the Pentagon—and to Restore It Sixty Years Later, by Steve Vogel, Random House, 626 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, hardcover, $32.95.

The Pentagon: The Untold Story of the Wartime Race to Build the Pentagon—and to Restore It Sixty Years Later, by Steve Vogel, Random House, 626 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, hardcover, $32.95.

The Pentagon in Washington, D.C., home of the U.S. Department of Defense, is the five-sided symbol of America’s military might. As such, it was targeted by Muslim terrorists on September 11, 2001, as one of their foremost targets. But it is not easy to destroy the world’s largest office building. As Steve Vogel points out in his terrific “biography” of the Pentagon, the creation of the building (over six million square feet at a cost of $85 million) was one of the greatest public works feats in American history.

Begun in September 1941 and occupied 17 months later, the Pentagon was a marvel of wartime engineering and construction. It was also controversial from the start—from its location in a wasteland along the Potomac to the political battles that erupted around its design and costs.

Conceived by General Brehon B. Somervell, who pushed all opposition aside, the Pentagon was a larger-than-life project brought into existence by larger-than-life personalities—everyone from President Franklin Roosevelt to Secretary of War Henry Stimson to Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall to Colonel Leslie R. Groves, overseer of construction. For months, Groves simultaneously oversaw the building of the Pentagon and the Manhattan Project—the operation to build the atomic bomb—driving both to completion far faster than anyone thought possible.

From start to finish, Vogel’s The Pentagon is filled with fresh details never previously reported, including the oft-comical efforts of Somervell and Groves to hide the true cost and size of the Pentagon from Congress and the press, construction accidents and mishaps, the story of how a small group of black employees forced the Pentagon to integrate soon after it opened, the 1967 antiwar demonstration told from the perspective of those defending the building, the deterioration of the building over the years, and chilling new details about the September 11 attack and the inside story of the race to repair the building.

Vogel throws in a final irony. Convinced that the Army would not need the Pentagon after World War II, Roosevelt insisted it be built for conversion to an archives after the war. The extra steel and columns used so that floors could support heavy file cabinets gave the building reserve strength that helped it withstand the blow of a hijacked jetliner 60 years later.

Based on official documents and hundreds of interviews and oral histories from the builders, first occupants, and more recent historic figures, The Pentagon is a big, satisfying book filled with intriguing facts and behind-the-scenes stories that will not soon be forgotten. A “must read.”

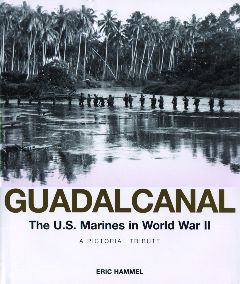

Guadalcanal: The U.S. Marines in World War II, by Eric Hammel, Zenith Press, 2007, 160 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, hardcover, $34.95.

Guadalcanal: The U.S. Marines in World War II, by Eric Hammel, Zenith Press, 2007, 160 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, hardcover, $34.95.

From Zenith Press and Eric Hammel comes another handsome, profusely illustrated tribute to the United States Marine Corps, this time focusing on the first major land battle involving American troops in the Pacific.

Following his earlier achievements with Iwo Jima: Portrait of a Battle and Pacific Warriors: The U.S. Marines in World War II, Hammel thrusts the reader into the hell and stench of battle on this Solomon island with both words and photographs, many of the most gruesome kind. Obsessed with Guadalcanal, Hammel pays tribute to the Marines’ spirit in his fourth book on the subject.

As this was the first fight for the half-trained Marine Corps against an experienced enemy, the fighting was savage, the conditions often unbearable. Even starvation was a very real threat. Men either learned swiftly the ways of jungle warfare or they did not survive. The six-month-long battle was the longest and most complicated operation the Marines would undertake during the entire Pacific campaign, and the lessons learned on this tropical battlefield would be applied by the leaders during the remainder of the war.

As the whole idea of assigning combat photographers to a battlefield was new to the Marines, relatively few photographs exist of the struggle. Hammel has spent years locating every known photograph of Guadalcanal, making this book, in his words, “the largest collection of Marines on Guadalcanal that has been published to date, or maybe ever will be published.”

Guadalcanal is truly an outstanding effort to document the sacrifice and struggle in America’s first stepping-stone on the path to victory over Japan.

The Story of the Spitfire: An Operational and Combat History, by Ken Delve, Greenhill Books, 272 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $25.95.

The Story of the Spitfire: An Operational and Combat History, by Ken Delve, Greenhill Books, 272 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $25.95.

To many people, the Supermarine Spitfire fighter aircraft is seen as the embodiment of British resolve during the Battle of Britain. Fast, maneuverable, and powerful, the Spitfire, the Hawker Hurricane, and a small band of brave pilots are generally credited with turning back the Luftwaffe’s formidable aerial armada and forestalling Hitler’s invasion of Britain.

But how justified was the legend? British aviation author and historian Ken Delve, using official sources and firsthand accounts, has written a superb history of this remarkable aircraft from its origins in the late 1930s to its last combat role during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Fighter Command pilots were thrilled with their new, state-of-the-art plane, but in terms of tactics and training the Royal Air Force was out of date. As air combat doctrine changed with the times and circumstances, the Spitfire and its pilots changed, too. Often, pilots with only a handful of hours in a training cockpit were thrown into battle; they either learned in a hurry or fell victim to the enemy’s firepower. Delve’s book tells all about what it was like to fight and survive at the controls of this remarkable aircraft.

Fortress Third Reich: German Fortifications and Defense Systems in World War II, by J. E. and H.W. Kaufmann, DaCapo Press, 2007, 369 pp., photographs, maps, technical drawings, index, bibliography, softcover, $22.95.

Fortress Third Reich: German Fortifications and Defense Systems in World War II, by J. E. and H.W. Kaufmann, DaCapo Press, 2007, 369 pp., photographs, maps, technical drawings, index, bibliography, softcover, $22.95.

When one thinks of German military fortifications, images of the huge concrete bunkers of the Atlantic Wall and Siegfried Line (West Wall) come immediately to mind. But there is so much more to what Germany accomplished in an unprecedented but ultimately unsuccessful effort to ensure its own defense.

The Germans of the World War II era were some of the most remarkable builders and engineers of all time, and much of their expertise went into the planning and creation of immense, innovative static defensive works made of nearly indestructible reinforced concrete—many examples of which survive to this day.

From the Arctic regions of Norway to the French-Spanish border, throughout Italy and the Balkans, and along the Eastern Front, Hitler and his construction team known as Organization Todt had transformed the Third Reich into the most fortified territory in history. Yet, despite the technically advanced ideas and superior construction techniques, even these fantastic fortresses could not stave off defeat.

Covering the gamut from individual armored foxholes to huge underground installations, Fortress Third Reich provides the reader with insight about how and why thousands of these formidable works—everything from concrete casemates, bunker lines, observation posts, resistance nests, air raid shelters, flak towers, beach defenses, submarine pens, “dragon’s teeth” antitank walls, V-1 and V-2 rocket-launching sites, and more—were built and how they were defeated.

The Kaufmanns, a husband and wife team, have captured the scope of German fortification building in this highly readable volume replete with fascinating and detailed engineering drawings by Robert M. Jurga. Very highly recommended.

Karl Brandt, The Nazi Doctor: Medicine and Power in the Third Reich, by Ulf Schmidt, Hambledon Continuum, 2007, 496 pp., maps, photographs, index, bibliography, hardcover, $29.95.

Karl Brandt, The Nazi Doctor: Medicine and Power in the Third Reich, by Ulf Schmidt, Hambledon Continuum, 2007, 496 pp., maps, photographs, index, bibliography, hardcover, $29.95.

Some 60 years after the end of World War II and the Nuremberg war crimes tribunal, interest in the major figures of Nazi Germany continues unabated. Here is the first full-scale biography of Karl Brandt, Adolf Hitler’s personal physician and one of the most powerful, behind-the-scenes figures of the Third Reich.

Ulf Schmidt recounts the meteoric rise of one of Hitler’s most trusted advisers, Reich Commissioner for Health and Sanitation Dr. Karl Brandt. It was Brandt who was a leading figure in the Nazis’ euthanasia program, the plan to exterminate physically and mentally handicapped children and adults, and who also played a key role in the use of concentration camp inmates as human guinea pigs for fiendish medical experiments. Schmidt examines the factors that led Brandt, and hundreds of other German physicians, to repudiate their Hippocratic oath and become instruments of torture and sadism for the sake of a twisted ideology.

The author also presents an incisive study of Brandt’s seizure of political power and explores the contradictions of Nazi medicine in which the care for wounded soldiers and civilians existed side by side with the brutal treatment and murder of tens of thousands of innocent, “unwanted” people. Brandt’s eventual capture and trial at Nuremberg in 1947 are also described in detail.

Schmidt’s book is a chilling, lasting reminder of the horrors perpetrated by the Third Reich.

They Fought at Anzio, by John S.D. Eisenhower, University of Missouri Press, 2007, 306 pp., maps, photographs, index, bibliography, hardcover, $34.95.

They Fought at Anzio, by John S.D. Eisenhower, University of Missouri Press, 2007, 306 pp., maps, photographs, index, bibliography, hardcover, $34.95.

Written by the son of the Supreme Allied Commander of World War II, They Fought at Anzio is a gripping tale of every aspect of one of the most costly and controversial of all military operations.

Drawing upon official documents and first-person accounts of soldiers who were there, Eisenhower offers a new look at the Italian campaign with an emphasis on Operation Shingle, the invasion of Anzio, just 40 miles from Rome. The operation, conceived by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill as a way of outflanking the stalemate that had developed across Italy and was centered on Monte Cassino, was visualized as an amphibious “end run” behind German lines in January 1944 that would force the enemy to evacuate Italy and head for the Alps.

As events proved, however, Anzio became a second stalemate, and the invading force of British and American troops came close to being wiped out. Only with indomitable courage shown by the individual soldiers were the Allies able to prevail and break out from their surrounded beachhead five months later, spearheading the successful drive to capture Rome.

Eisenhower brings his trained military eye to reconstructing Anzio’s difficult terrain, and approaches the Anzio battle as a contest between opposing commands striving to anticipate and counter each other’s moves—not as a field exercise but as a deadly struggle for survival and victory. He analyzes the command decisions that brought about the stalemate, interspersing his account with personal experiences of the men in their water-filled foxholes. His book adds to the growing body of literature about one of the most frustrating, least understood battles of World War II.

French Resistance Fighter: France’s Secret Army, by Terry Crowdy, Osprey Publishing, 2007, 64 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, softcover, $17.95.

French Resistance Fighter: France’s Secret Army, by Terry Crowdy, Osprey Publishing, 2007, 64 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, softcover, $17.95.

Although small in terms of number of pages, this book is packed with information and details about a military force that has historically received little coverage. Working as an underground force, the Maquis, or French Resistance, was initially formed spontaneously from scattered groups of the displaced and discontented after the 1940 German invasion and occupation.

As the war progressed, the resistance developed into Charles DeGaulle’s secret army, terrorizing the occupying forces and would-be collaborators alike. Although they were not protected by the Geneva Convention and faced torture, execution, or deportation to concentration camps if captured, the Maquis fought on, sabotaging German installations and lines of communication, often helping to save downed Allied airmen, and working to liberate Paris and other cities before the Allied armies marched in.

Striking photographs and full-color illustrations by Steve Noon, coupled with firsthand accounts of the dangers faced by the resistance fighters, create a personal portrait of men and women willing to risk everything to free their country. Crowdy details the military achievements, tactics, backgrounds, and motivations of the brave patriots whose assistance helped ensure the success of the D-Day landings and eventual French liberation.

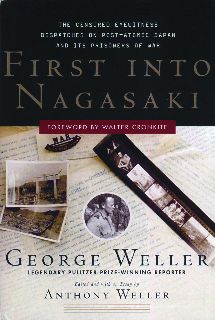

First Into Nagasaki: The Censored Eyewitness Dispatches on Post-Atomic Japan and Its Prisoners of War, by George Weller, edited by Anthony Weller, Crown Publishers, 2007, 288 pp., maps, photographs, index, bibliography, $25.00.

First Into Nagasaki: The Censored Eyewitness Dispatches on Post-Atomic Japan and Its Prisoners of War, by George Weller, edited by Anthony Weller, Crown Publishers, 2007, 288 pp., maps, photographs, index, bibliography, $25.00.

The Chicago Daily News’s Pulitzer Prize winning reporter George Weller was, as the title of his book says, the first American reporter and outside observer into the atomic bomb-blasted city of Nagasaki. In defiance of a military imposed news blackout, Weller disguised himself as a U.S. Army colonel and began to document what he saw.

His initial dispatches were stoic and dispassionate, but as he observed the effects of radiation on human beings, his tone changed. He then entered the nearby POW camps, where American and Allied prisoners had been confined and tortured. General MacArthur was furious at Weller for violating censorship rules and he heavily censored his reports. Weller somehow misplaced his only surviving carbon copy of the dispatches, and he died in 2002, thinking the copy was lost forever.

After his death, Weller’s son Anthony, himself an award-winning journalist, discovered the missing carbon copies along with numerous unseen photographs in a crate full of his father’s papers and knew they had to be published. Fortunately, George Weller’s eloquent accounts of what he discovered in and around Nagasaki have been resurrected to provide a unique perspective about the final stages of World War II, about the fate of a Japanese city and its residents, and about the brutal treatment of prisoners of war by their captors.

Weller’s story is a reminder of the media’s most important responsibility: to uncover facts and inform the public of the truth. The publication of First Into Nagasaki accomplishes the mission Weller began six decades ago: to tell a story that for too long has gone untold.

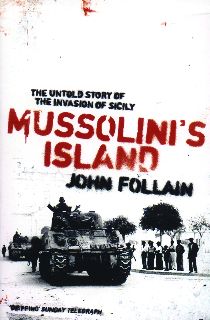

Mussolini’s Island: The Untold Story of the Invasion of Sicily, by John Follain, Hodder & Stoughton, 2007, 288 pp., maps, photographs, index, bibliography, softcover, $15.95.

Mussolini’s Island: The Untold Story of the Invasion of Sicily, by John Follain, Hodder & Stoughton, 2007, 288 pp., maps, photographs, index, bibliography, softcover, $15.95.

In July 1943, following their hard-won triumph in North Africa, the Allies launched their first assault against Hitler’s “Fortress Europe” by invading the Italian island of Sicily.

In many ways, the invasion of Sicily, Operation Husky, was a dress rehearsal for the Normandy invasion—a triphibious (air, land, and sea), multinational coalition effort involving 180,000 troops, 3,200 ships, and over 4,000 aircraft, with armies commanded by General Bernard Montgomery and General George S. Patton (and General Omar Bradley as a corps commander) and the whole show orchestrated by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander.

Given the amount of manpower and firepower, Operation Husky should have been a brief, violent assault that quickly subdued enemy opposition. As it turned out, it was a month-long ordeal that involved tragedy, fiascos, infighting between the Allies, and a lost opportunity that allowed thousands of German and Italian troops to slip across the Strait of Messina and onto the Italian mainland, thereby prolonging the contest in the Mediterranean.

Using first-person accounts from U.S., British, Italian, and German participants in the campaign, author Follain weaves gripping personal accounts into the overall battle scheme to vividly paint a detailed picture of how things go right and wrong in war.

Mussolini’s Island is a powerful new history of this important but often overlooked battle, with unforgettable stories about the horrors and heroism that take place on the battlefield.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments