By Robert F. Dorr

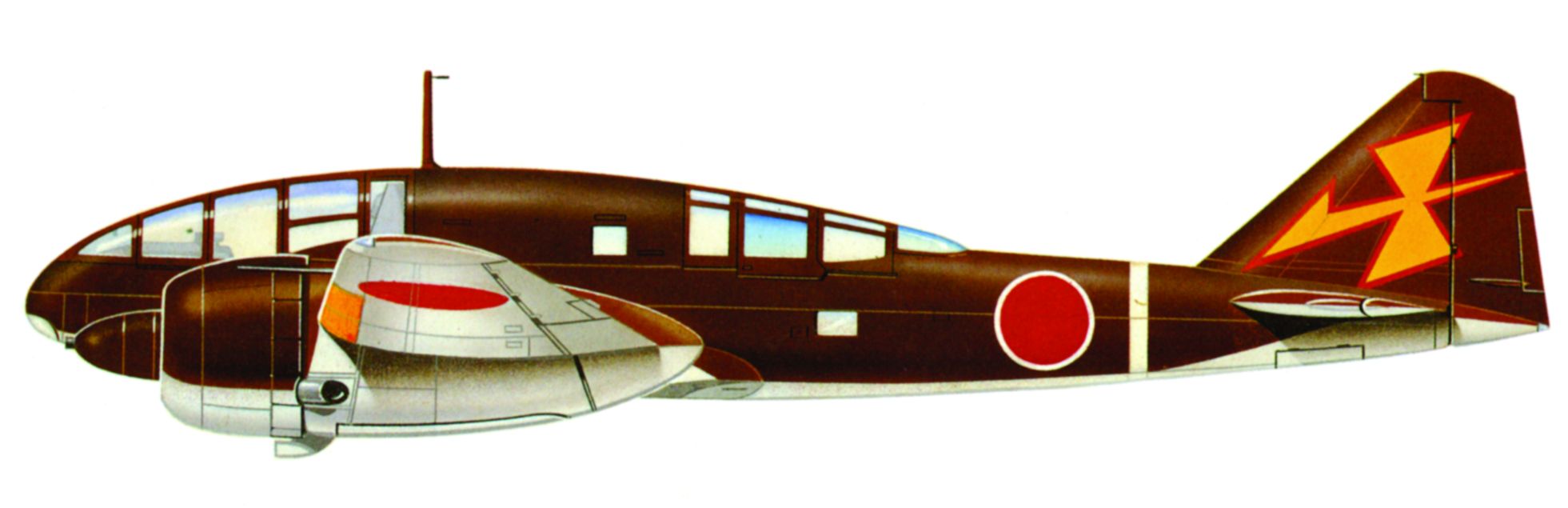

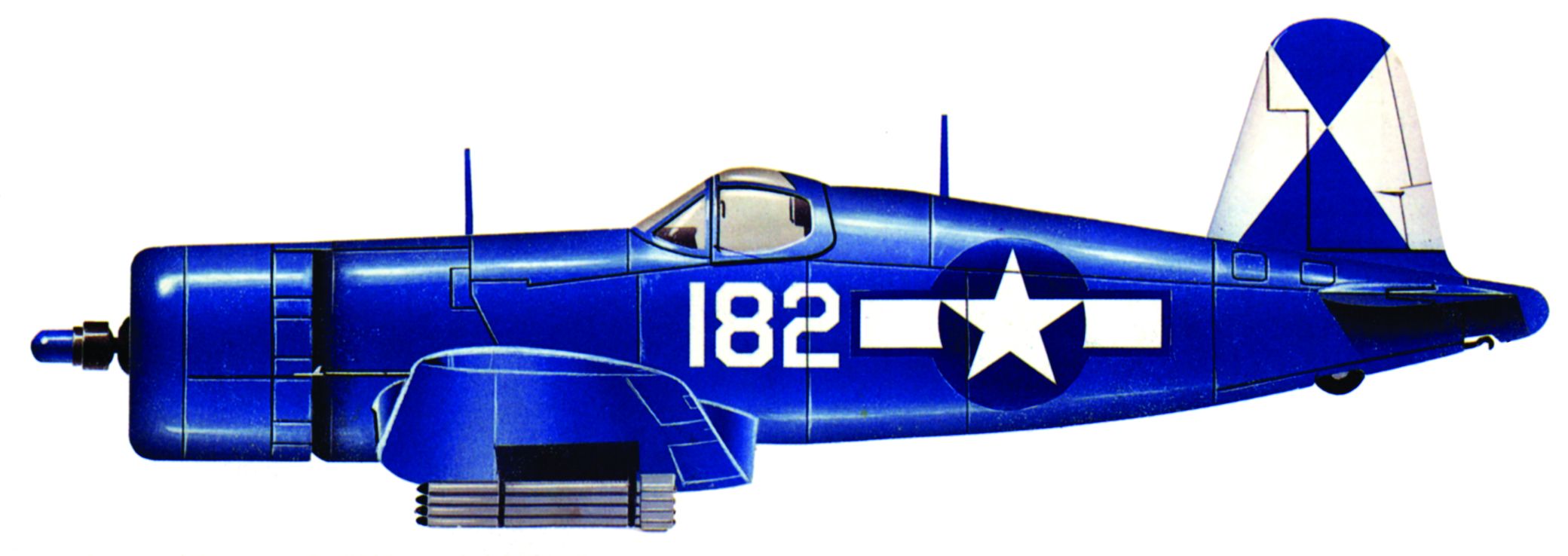

When the Marines put Willis “Bud” Dworzak into the cockpit of a Vought F4U-1C Corsair fighter aircraft, they expected him to provide close air support to fellow leathernecks who were slugging it out on Okinawa. Dworzak did. But he also used the blue, gull-winged, radial-engined Corsair to rack up an aerial victory. On May 11, 1945, Dworzak fought a kind of “one-man war” with a Japanese twin-engined Mitsubishi Ki-46 Army Type 100 fighter and reconnaissance plane, known in Allied parlance as a “Dinah.”

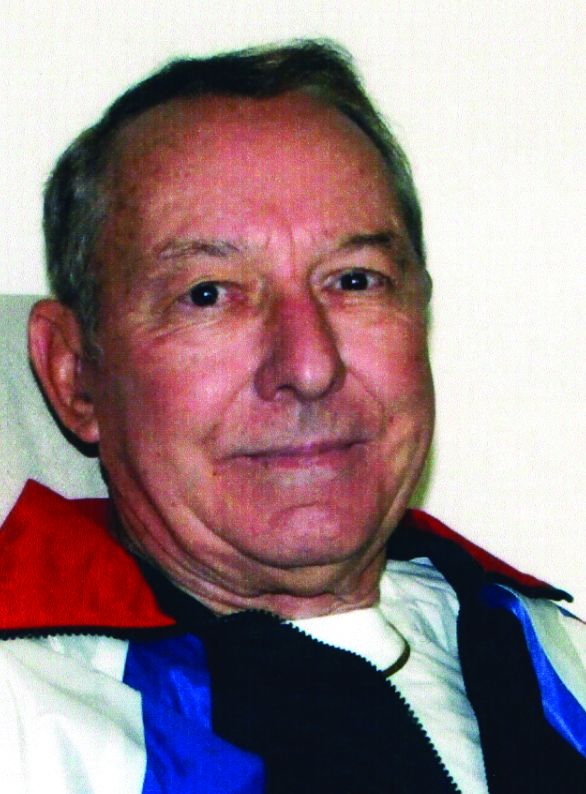

It was an extraordinary shootdown, coming very late in the war when many believed air-to-air combat had ended. Dworzak, who looked even younger than his 22 years, saw himself as “just a young guy who wanted to fly” but had also told a recruiter he wanted “to kill Japs.” The Marines enabled him to fly and fight at the controls of one of the best-loved aircraft of the war.

RFD: So you were one of those young kids who always wanted to fly?

BD: That’s me. My sister and I took our first airplane ride in Oakhurst, New Jersey, when we were about eight or nine years old. I don’t know what kind of plane it was. It was a bi-plane, probably a Waco or a Standard. That hooked me on flying. Growing up in New Jersey during the Depression years, I read airplane magazines and built model airplanes.

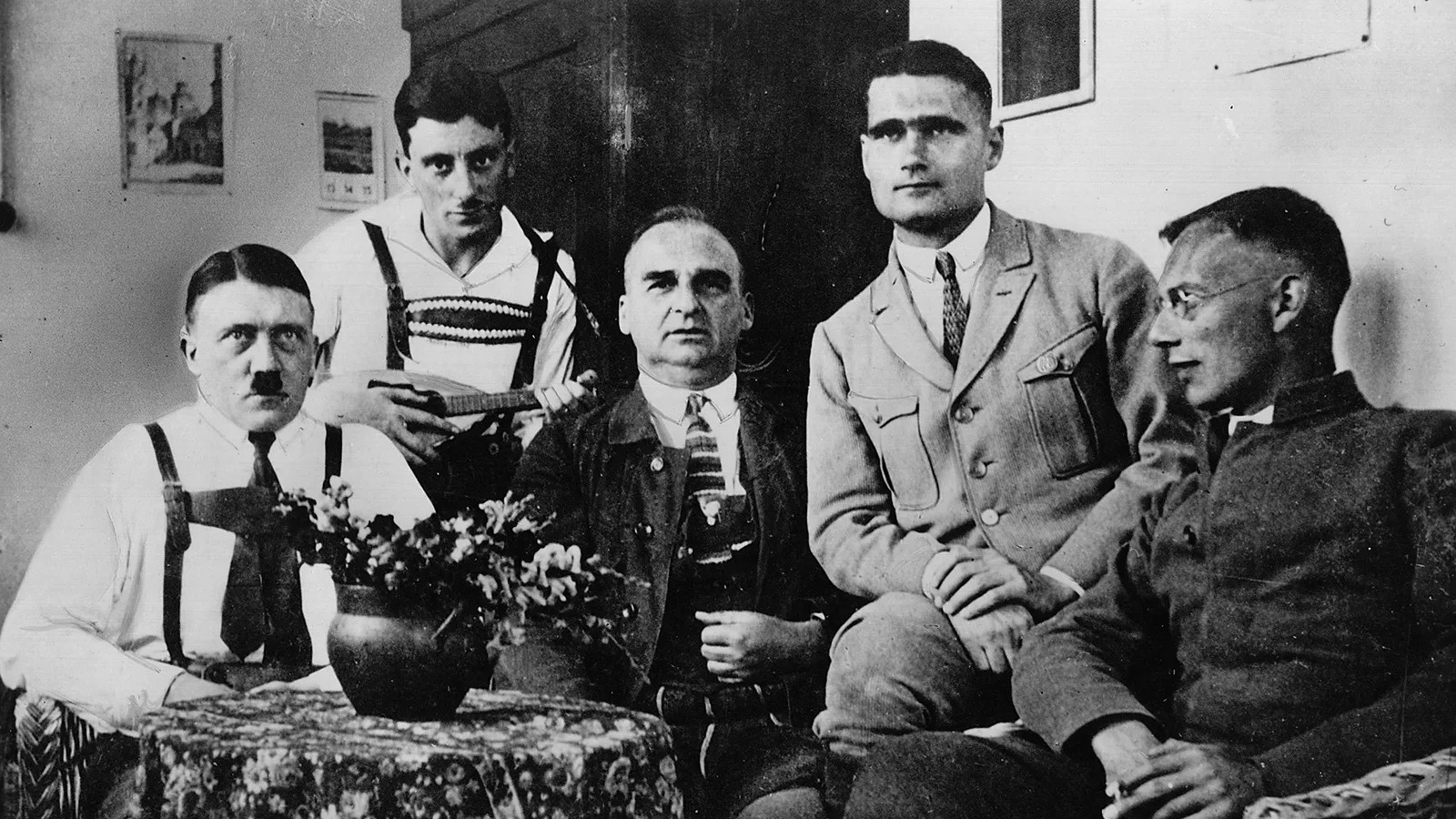

RFD: Do you have a memory of how you learned the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor?

BD: Well, first I should tell you that I was in uniform before that. I got a very early start.

RFD: Before Pearl Harbor? Weren’t you too young?

RFD: Before Pearl Harbor? Weren’t you too young?

BD: Yes. I was born in 1923 in Asbury Park, New Jersey. When I was in high school in 1938, a buddy told me about National Guard service. “You go down to the armory and drill once a month,” he told me. “They issue you a rifle and a uniform. It’s very neat. It’s like the real thing.”

I was 15 years old. They never checked birth certificates in those days. So I went with my buddy and, suddenly, here I am, in the New Jersey National Guard.

In 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt activated the Guard. I’m still under age, but now I’m a member of the United States Army. We hung around the armory as part of Company G, 114th Infantry, 44th Division. It was “hurry up and wait” as we wondered what they would do with us.

My mom said, “You’ve got to finish high school.” I went to my commanding officer, Captain Harris, and told him I needed to go back to high school. He looked at me and said, “How old are you?” He wasn’t mad or anything. I was now 17 but did not have my parents’ consent. Harris said I was too young and sent me home. I got an honorable discharge from the United States Army that year.

RFD: Can you recall how you learned the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor?

BD: I graduated high school in June 1941 and started junior college. I was living in Asbury Park. I heard about it on the radio. I had studied geography in school. I knew where the Hawaiian Islands were and what they were talking about. I also knew that I never wanted to be a rifleman again. I wanted to fly.

RFD: What happened then?

BD: In the first days of World War II, you still needed four years of college to become a pilot. I went to Monmouth Junior College. In 1942, I also started pilot training at Asbury Park under the Civil Pilot Training (CPT) program. This was a government program encouraged by the Roosevelt administration that introduced aviation to thousands who later flew in the war. I was working in a blueprint shop, studying, and getting flight training during my lunch hour in the CPT program. I soloed a Piper J-3 Cub after eight hours of instruction, which was about average.

The government paid for 10 hours of flying training under this program. A private pilot’s license required 35. A local Rotary Club stepped forward to pay for the full 35 hours for the best student pilots in our group. One guy beat me out for the top of the class. He had a score of 95.5, and I had 95.4.

Part of the requirement for a pilot’s license was a cross-country flight in a triangle in which at least one leg was 100 miles long. Because of our location near the New Jersey shore, we couldn’t fly a 100-mile leg because of wartime flight restrictions, so I made a cross-country flight of lesser distance and got a restriction on my license, which didn’t mean much.

When I finished my first year of college, they reduced the requirement for military pilot training to two years of college. I figured, “I’ve got one more year. I can do that coasting.” I was in my second year of college when they reduced the requirement to high school only. That was in August 1942, and I immediately went to 120 Broadway, the Navy recruiting office, and was sworn in as an aviation cadet. They told me to go home and wait to be called.

RFD: Was that the program that covered training for all naval aviators—Navy, Coast Guard, and Marine?

BD: Yes. But almost immediately, I learned of a better program that required a private pilot’s license, which I had. I went back to 120 Broadway and talked to a chief petty officer. Now it’s September or October of 1942, and I said, “I can’t wait any longer. I want to go in.”

He said, “What do you want to do?” I said, “I want to kill Japs.”

He said, “Wait a little longer, kid. If you want to kill Japs, this isn’t the program for you. Under this program, you’ll go for 90 days to Officer Candidate School. You’ll go to Pensacola and get your wings. And you’ll become a flight instructor. You’ll be teaching all those young men who will go out and kill Japs while you stay in Florida.” He said, “Go home. I’ll call you when we have the job you want.” So I went home, and at the end of December 1942, I was told to report on January 1, 1943.

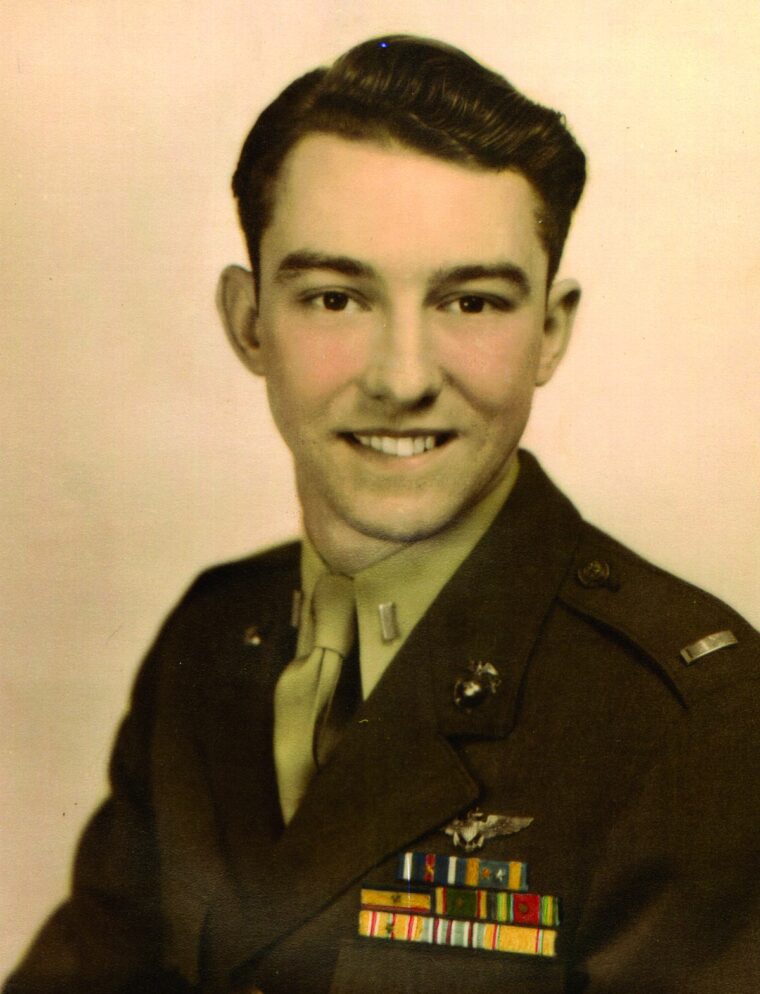

Initially, it was like being a volunteer. The naval aviation program was like a contract. You had an obligation. The government had an obligation. You were free to quit any time you wanted. I was in training when they changed all that with a measure called “Sign or Resign.” You could quit on the spot or you signed away your right to quit. I got my wings in October 1943. I had already decided that the best way to kill Japs was go into the Marine Corps.

RFD: Many with an interest in aviation will envy you for flying the Corsair, one of the great fighters. Did you know from the start that you would get the Corsair?

BD: Not at first. After winning my naval aviator’s wings, I went to El Centro, California, and studied bombing in the [Douglas] SBD Dauntless. Then, they formed a new squadron, VMF-462, in June 1944. It had the FG-1D, the Goodyear-built version of the Corsair. I was in 462 briefly and transferred out. We went overseas as replacements. I spent Christmas Day 1944 in Pearl Harbor. We floated around the Pacific for a while. We joined squadron VMF-441, also called the Black Jack Squadron and part of Marine Air Group 31, or MAG-31, in January 1945 on Roi-Namur, Kwajalein atoll, Marshall Islands.

Colonel Charles Lindbergh flew with VMF-441 as a technical adviser for United Aircraft [which owned Vought-Sikorsky, later called Chance Vought], several months before I arrived. The pilots who flew with Lindbergh said he was a very professional, precision pilot and after each mission landed with more fuel remaining in his tank than any of the other pilots. He also redesigned the Corsair bomb racks to carry a 2,000-pound bomb on the centerline rack and a 1,000-pound bomb on each of the two pylon racks, giving the Corsair a bomb load capability of 4,000 pounds.

While on Roi-Namur, the squadron participated in training missions, including introduction to aircraft rockets, and bombing and strafing strikes against bypassed Japanese islands. When we were briefed for dive-bombing missions, we were told not to get below 2,000 feet on our bombing runs because the Japanese antiaircraft gunners were deadly at that range.

They decided to put 441 aboard the escort carrier USS Sitkoh Bay (CVE 86), which transported us to Okinawa.

RFD: So, the Sitkoh Bay was being used as a ferry, in effect, just to get you there?

BD: Yes. But we did pull catapult alert while en route. I was designated as an alert pilot. Every morning at daybreak, they would sound general quarters. I would report to the ready room. I got briefed. I sat on the catapult there in my Corsair. If a Japanese plane was spotted, I would be launched in my Corsair to shoot it down.

One day, shortly before the invasion, we got the order: “Alert pilots, man your aircraft!” I grabbed my charts and ran up to the deck. I scrambled into the cockpit. That’s when I saw Lt. Col. Munn, the CO of MAG-31.

He said, “Get the hell out of my airplane.” Then, he relaxed a little and said, “That’s all right, son, I’ll take this one.” He was taking my job away from me! But before he even got his engine fired up, the Japanese aircraft turned away and they called off the alert.

RFD: How did you get along with the sailors on the Sitkoh Bay?

BD: Before we left the USS Sitkoh Bay, the ship’s crew fabricated medals for the pilots from 5-inch gunfire shells, and the cloth was from LSO signal paddles. Stamped on the polished brass cross was, ‘VALOR—SITKOH BAY—COST—1 JAP.’ It was formally presented to each pilot with a written citation. Mine said that Lieutenant Dworzak “did, without regard for his personal safety and convenience, and far beyond the call of duty, deposit himself upon various bunks of this vessel for long hours during the day and night in the face of concerted opposition from wind, sea, and subversive elements,” whatever they were. It also said that I “zealously and rigorously reported to the Wardroom at meal times.” The funny thing is, the “Valor Cross Sitkoh Bay” looks like a real medal when it’s really just a nice gesture of affection from the crew.

RFD: Tell us about the Corsair.

BD: The Marine Corps was lucky to benefit from the hard luck the Navy had with the Corsair. It was manufactured by three companies, Vought-Sikorsky, the prime contractor, as the F4U; Goodyear, as the FG; and Brewster, as the F3BD. They came out with six 50-caliber machine guns, although I later flew the F4U-1C with four 20-millimeter cannons.

It started out with wet wings [prototypes] that leaked. They put a 240-gallon fuel tank right behind the engines. The tank on the fuselage did leak a little. They put pink-edged tape over it. They put it there with airplane dope. When the pilot was approaching to land on the carrier, he would lose sight of the landing signal officer, or LSO, just as he was on his final approach. The British learned how to use the Corsair on a carrier before we ever mastered it. They would keep it in a turn until they’d just approached the LSO on the flight deck. Just as they got over the edge, they would come out of the turn all lined up.

The Corsair was not the easiest plane to fly, but it was comfortable enough. I’m six feet tall and weighed about 150 pounds then, and I never had any trouble getting into the Corsair cockpit. The rudder pedals were a little difficult to reach. Otherwise, it was a pretty sensible design.

RFD: The battle for Iwo Jima was already taking place in February 1945, as you prepared to embark on the Sitkoh Bay. Did you know where you were going?

BD: No. I knew only that our squadron, VMF-441, the Black Jack Squadron, was going to be land based. In March 1945, they loaded our airplanes on scows at Roi-Namur and took them out to Jeep carriers, and off we went to Okinawa.

RFD: Did you get to witness the invasion of that island?

BD: No. Invasion day was April Fool’s Day in 1945. Our ship wasn’t off Okinawa when they were doing the invasion. We got there a few days later. We catapulted off of Sitkoh Bay on April 7. The battle was still going on, of course. There was fierce Japanese resistance on Okinawa.

RFD: So it was a relatively routine flight, going smack into the middle of an island where a major battle was going on?

BD: No Japanese fired upon us that day. But we faced serious airmanship challenges. The Sitkoh Bay was still about 100 nautical miles south, so it was about a one-hour flight. We needed control trim tab settings for takeoff on the catapult, but the Sitkoh Bay’s catapult officer had never launched Corsairs before.

One of our pilots said he had catapulted before and as best as he could remember you needed normal tab settings except for the elevator trim. There, you used five degrees back tab. We were the second four-plane division to take off. The first plane went dangerously upward after clearing the cat. After seeing that, I rolled the elevator tab forward to only four degrees back tab. I felt the following pilots would make a similar correction, but because the next two Corsairs climbed excessively I made additional corrections on the tab settings. I think by the time I took off, I had neutral elevator tab.

RFD: And you went into Yontan airfield?

BD: Yes. As I said, MAG-31 went into Yontan on April 7. A few days later, our sister air group, MAG-33, went into Kadena. Decades later, when I was a civilian working in Vietnam, my plane made a refueling stop at Kadena and it looked entirely different, built up.

The Battle of Okinawa continued long after we arrived there. MAG-31 arrived with three Corsair squadrons, VMF-224, -311 and -441. On Okinawa, our air group picked up a night fighter squadron, VMF(N)-542 equipped with the Grumman F6F Hellcat. That was the other great U.S. Navy fighter of the war, and in a minute I’ll tell you how I think the Corsair and Hellcat compare. I flew F4U-1Ds in April and May. They were replaced with cannon-armed F4U-1Cs some time before June when Okinawa was declared secure.

RFD: Meanwhile, what were conditions like for you?

BD: At Yontan things were rather primitive. We lived right on the airfield, on the other side of the taxiway from where our aircraft were deployed. At first, we each shared a shelter half with another pilot. Later, pyramidal tents were provided, which we shared with three or four other Marines. Sometime in May the Seabees replaced our tents with Quonset huts.

I won’t say we lived like ground-pounding Marines, but it wasn’t the Ritz, either. Our flight schedules prevented eating at scheduled mealtimes, so meals were provided at odd times at the alert shack. The meals were “GI” but I don’t remember anyone complaining. One morning when scheduled for dawn combat air patrol, or CAP, several of us were having breakfast at about 0400 in the alert shack. Pistol Pete, a Japanese howitzer, was lobbing shells up from down around Naha, and they were exploding on the field, and each one was getting closer. We knew if he continued, the next one would be really close, but no one was getting excited. The next round landed on the ground behind the alert shack with a thud. We were lucky. The darn thing was defective and didn’t explode.

RFD: You were going to compare the Corsair and the Hellcat?

BD: My high school buddy, Ensign Paul Glasser, was flying F6F Hellcats with the Navy on the carrier USS Randolph (CV 15), and one day he dropped in at Yontan to visit me. My F4U-1C Corsair was mired in mud, but they parked Paul on pavement. I remember I was wearing rubber boots, and he had nice, polished shoes. I thought, “He’ll be having a steak dinner on the Randolph and sleeping between clean sheets tonight. I’ll be sleeping in a tent, in my skivvies, on an Army cot with a green Marine Corps cover, with a loaded .45 automatic under my pillow.”

We were going to fly against each other, but it didn’t happen. We experienced a curious and bizarre moment when I could not climb into my Corsair because of the mud. I tried to climb up on the wing, the first step toward crawling into the cockpit, and my muddy boots slipped and slid. I tried it several times and fell off the wing twice. Finally, I had to straddle the rear fuselage and shimmy up to the cockpit. Paul stood there in his nice, polished shoes, holding his hands at his sides, laughing.

Not long after that embarrassing moment, our hard-working ground crews built a wooden stand with a three-step ladder on one side and a platform on top. This way, we could get in the cockpit and kick off most of the mud on our boots before stepping in on the parachute that was already in place on the seat.

I later flew the F6F Hellcat briefly after the war. The Hellcat was very stable but not as nimble as the Corsair. You could do a real snappy roll in the Corsair, but not the Hellcat.

The Hellcat was much easier to fly. The Corsair wasn’t easy at all. When you landed it, you had to fight it to a standstill. You put your wheels on the ground and congratulated yourself for defeating gravity again, and suddenly you realized that your Corsair wasn’t slowing down. It had a tendency to veer off the runway. The F6F, in contrast, would just about land itself.

RFD: Mud. A plane that’s difficult to land. It was not a piece of cake on Okinawa, was it?

BD: As in any war, there were the mishaps you regretted. Some killed people. Some didn’t. One of our planes accidentally dropped a belly tank on the runway when we were all taxiing out. A Corsair taxied over it and chewed it up with the propeller blade, carving out slices four to six inches apart and sending fuel and metal fragments all over the place. I was able to make an S-turn and taxi around it.

RFD: Did you support Marines on the ground in combat?

BD: We always took pride in that. The Corsair turned out to be a very effective air-to-ground weapon. Captain Roswell “Rob” Raber, who was usually leading my buddies and me, especially liked the 5-inch high-velocity aircraft rockets, or HVAR, we slung under the wings.

We carried eight 5-inch HVAR rockets. If you fired it in salvo, you had the equivalent in firepower of a broadside from a destroyer. I received very little training in rocket firing. I didn’t know what to expect. On my first run, I was not satisfied that Raber was lined up on the right target. Still, we made three runs. Each time, I wasn’t satisfied that we were on the right target and therefore withheld fire On our fourth run, the controller told us it would be our last run. We knew there were Japanese troops dug in, hunkered inside a building straight ahead of our flight path, and this time there was no doubt we had a real and valid target.

The controller said, “Expend all your weapons.” I set my switch on Salvo. On Salvo, they fire in pairs from inboard to outboard. I was the last one in on the target and therefore was very intent on destroying it. I came in at treetop level, and when on target I squeezed the trigger. The rockets fired in pairs, one after the other, all eight of them. They went right into the front door of the building. I wasn’t planning to fly through the building, but that’s exactly what happened. The building exploded and was completely demolished. And I went right through it.

I burned up the rear of my Corsair by firing all those rockets. The leading edges of the wing and tail of my Corsair were severely damaged. The tail wheel, which hangs out in the open while you’re in flight, was burned flat. I brought my Corsair back to the flight line and my plane captain said, “Lieutenant, take that right down to salvage at the end of the parking area.” Salvage was the wrong term, though. By that time in the war, we had plenty of airplanes, and I’m sure that one never flew again.

RFD: You did a great job with air-to-ground work. But you also had a chance to go after a Japanese aircraft.

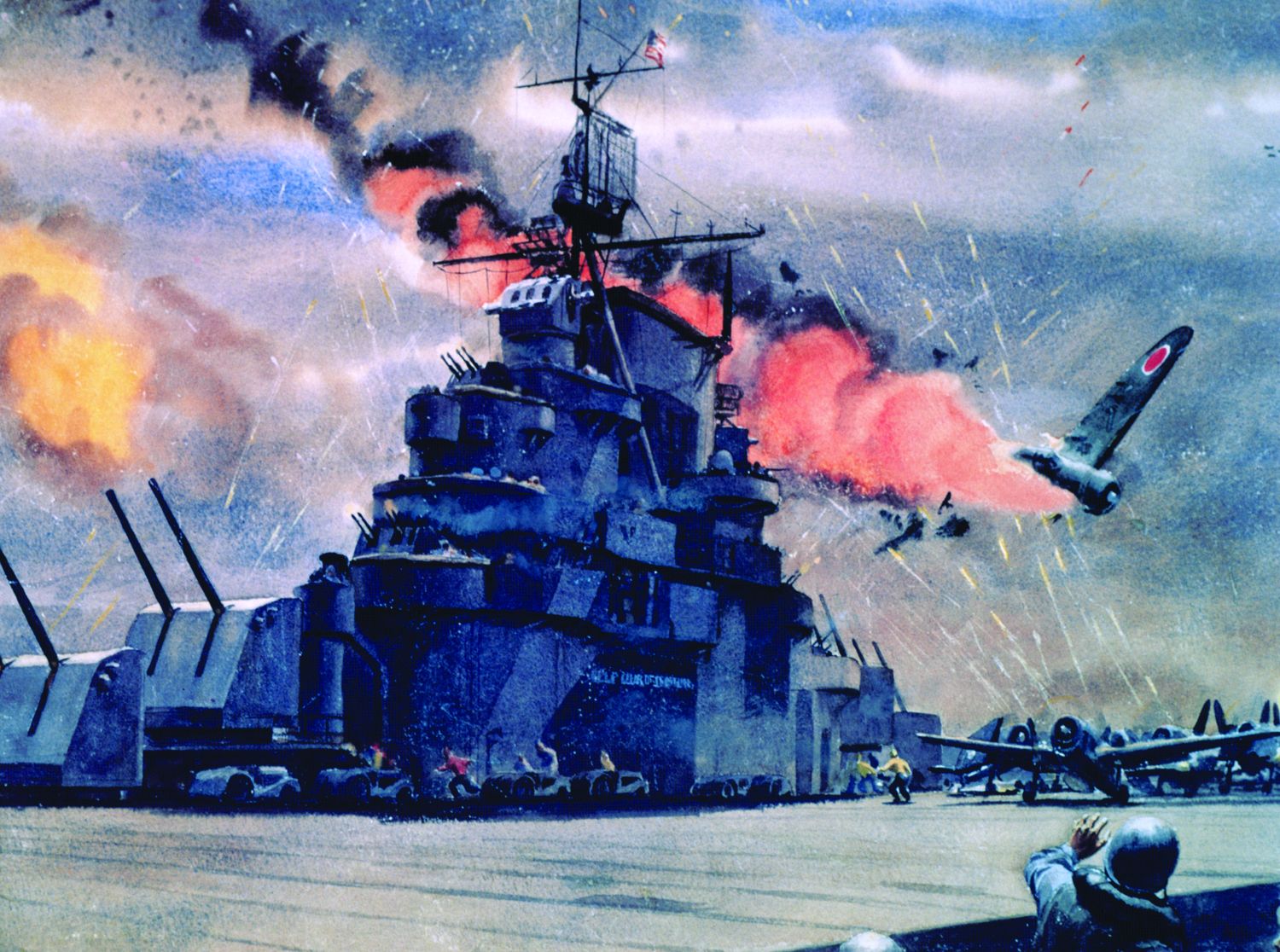

BD: Many of the fighter units in and around Okinawa were tied up trying to intercept and shoot down the Japanese suicide pilots, the kamikaze, who were attacking constantly and inflicting heavy damage on the fleet. My own squadron only engaged kamikaze once or twice, but we were aware of them constantly. Today, not many people remember how much harm they did, but they were a persistent threat and they caused high American casualties.

RFD: Did you have an encounter with a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft?

BD: I did. On the morning of May 11, 1945, I was flying a combat air patrol mission with my division leader, Raber. A division is the naval term for a flight of four aircraft. First Lt. Charles Whipple was flying wing on Raber. First Lt. Robert Kane was leading the second section, a section being the term for a flight of two, and I was flying wing on Kane. I was flying a brand new F4U-1C.

We were approximately 30 miles east of Okinawa flying at 12,000 feet in a wide orbit around our radar picket station, which was made up of two destroyer escorts, or DEs, and four “small boys.” The small boys consisted of various types of landing craft such as landing ships tank, or LSTs, and landing craft infantry, or LCIs.

Shortly after we arrived on station, our shipboard radar operators picked up a bogey on their search gear and vectored us on a northerly course to intercept it. We asked our controller for the altitude of the bogey, but they were unable to provide us with that information because of the limitations of their early equipment. However, they were able to give us approximate distance to our target.

RFD: It’s morning. It’s daylight. But radar controllers are vectoring you. You don’t have visual contact with the bogey, right?

BD: That’s right. As we closed in, our controller told us the bogey was five miles ahead of us. Whipple spotted an unidentified aircraft several miles off his left wing. Radar confirmed it to be our intended target, and Raber brought our division around behind the bogey, which by now was several miles ahead of us.

Raber signaled for us to form into a pursuit formation, which brought all four aircraft in-line, abreast, and several hundred yards apart. That put me on the extreme starboard end of the formation.

For some unknown reason, the bogey made a 90-degree turn to starboard. Now, in the division formation, I was in the position closest to the bogey. I called Raber on the radio for permission to attack the bogey but got no answer. Rob Raber frankly wasn’t as aggressive as I felt he should have been. After I repeated my call, Whipple came back with, “Go get him Bud!”

I immediately applied significantly more power and dropped my belly tank. When I got closer, I was able to identify the bogey as a Dinah, an armed high-altitude, twin-engine aircraft.

RFD: That would be a Mitsubishi Ki-46 Army Type 100 fighter. The Allies assigned code names to Japanese airplanes, sometimes inspired by famous people. The Ki-46 may have gotten its code name from the singer and entertainer Dinah Shore.

BD: Yes, and we had been briefed on it. But I wasn’t sure if the Dinah had a rear gunner, so I squeezed off a few rounds while still well out of range and said, “Oh, son of a bitch!” I was horrified to see that my cannons had not been bore sighted. My ammo was belted with armor piercing, tracer, ball, and high-explosive/incendiary shells, so I could see some of the tracer and high explosive/incendiary rounds hitting way out on the left wing tip.

There were some broken clouds below at 5,000 feet, where he could hide until it was safe for him to complete his mission of reconnaissance and kamikaze. When I fired, the Dinah started down to the clouds below, so I moved the pipper [sight] over to the starboard engine and held the trigger down.

I could see tracers going out all over the place, instead of forming a V with the apex at the target. I’m closing on him now. He’s heading down for a bank of clouds. There are ships off to my left. It might have been the picket ship that was vectoring us. I didn’t want this guy getting down and hitting any ships. I just held down on the trigger. Then things started happening all of a sudden. Lots of pieces started flying off the Dinah. I was overtaking the Dinah rapidly.

My guns quit. I had used up all 200 rounds per gun, and as we were going into the clouds the left wing of the Dinah broke off. I had to put a violent input into my control system as I was overtaking him, to avoid hitting him. His left wing was completely shot off by that time. He was spinning in. When I came out below the clouds, I could see the Dinah was in a flat spin as it hit the water and exploded. I was credited with the kill. I got an Air Medal for that.

A few miles south of us there were several ships that probably included our radar controller. The ships had already sent up several rounds of antiaircraft fire and were ready to take on the Dinah if it had come out of the clouds in one piece.

RFD: That is every fighter pilot’s goal—an aerial victory. But the war continued for you, didn’t it?

BD: Yes. May 24 was an exciting day (and night). On Okinawa a pilot was always on duty in the control tower. That day, I was assigned as the control tower duty officer. A night fighter pilot relieved me before dusk just when enemy activity was noticeably increasing.

We might have thought the enemy’s air force was knocked out, except for the kamikaze aircraft that made such a huge impact during the Okinawa battle. But that night, Japanese aircraft bombed and strafed our airfield for three or four hours. Then, Jap planes loaded with suicide troops attempted to land at Yontan. Our intense antiaircraft fire shot down seven of them. However, one came in silently, with engines cut, for a perfect belly landing about 100 yards from the tower.

At first, the night fighter pilot in the tower started using the signal lamp, with a clear lens, to spot the Japs for the Marines who were resisting the attack as the suicide troops left their aircraft for designated targets. Unfortunately, the night fighter pilot who had relieved me just a few hours before was killed by one of the suicide troops as he climbed down from the tower to get closer to the action.

RFD: That attack was kind of a last gasp, wasn’t it? After things settled back to normal following the attack, did your squadron fly missions against the Japanese mainland?

BD: Having new Corsairs gave our squadron high aircraft availability for assignment to choice missions such as fighter sweeps on Kyushu. Our squadron did, in fact, fly up to Kyushu to attack targets on the mainland, but I didn’t get in on any of those missions. The war ended before I could see combat over the Japanese mainland.

RFD: Tell us about your life afterward.

BD: I continued flying in the Marine Corps and made the postwar transition to jets. In addition to Corsairs and Hellcats, I piloted the F9F-6 and F9F-7 Cougar at Floyd Bennett Field, New York, in a reserve squadron.

Later, I was a civilian working for the Army at Fort Monmouth near my home in New Jersey. They sent me to Vietnam. After I persuaded my bosses that a civilian could fly airplanes in combat, I flew 14 combat support missions in a DeHavilland U-6A Beaver. It had dual controls, and I always had a co-pilot with me.

I retired from my Army career in 1977 and still live in my hometown with my family. When I think of my experience in World War II, I realize I was too young and dumb to be scared.

Robert F. Dorr is an Air Force veteran, a retired U.S. diplomat, and author of the book Air Force One, a look at presidential aircraft and air travel.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments