By Al Hemingway

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pleasants of the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry was a melancholy man prior to his involvement in the Civil War. He had lost his wife to a debilitating fever, and her untimely death “had, in the span of a single day, drained all meaning from his life.” But that was all about to change for the morose officer. Pleasants’s unit was comprised of burly, hard-drinking miners from the coal region of Pennsylvania. They were a part of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps of the Army of the Potomac. The Union Army had fought its way to the very outskirts of Petersburg, Virginia, in 1864, but now was bogged down in a long siege after it had failed to seize the city in mid-June.

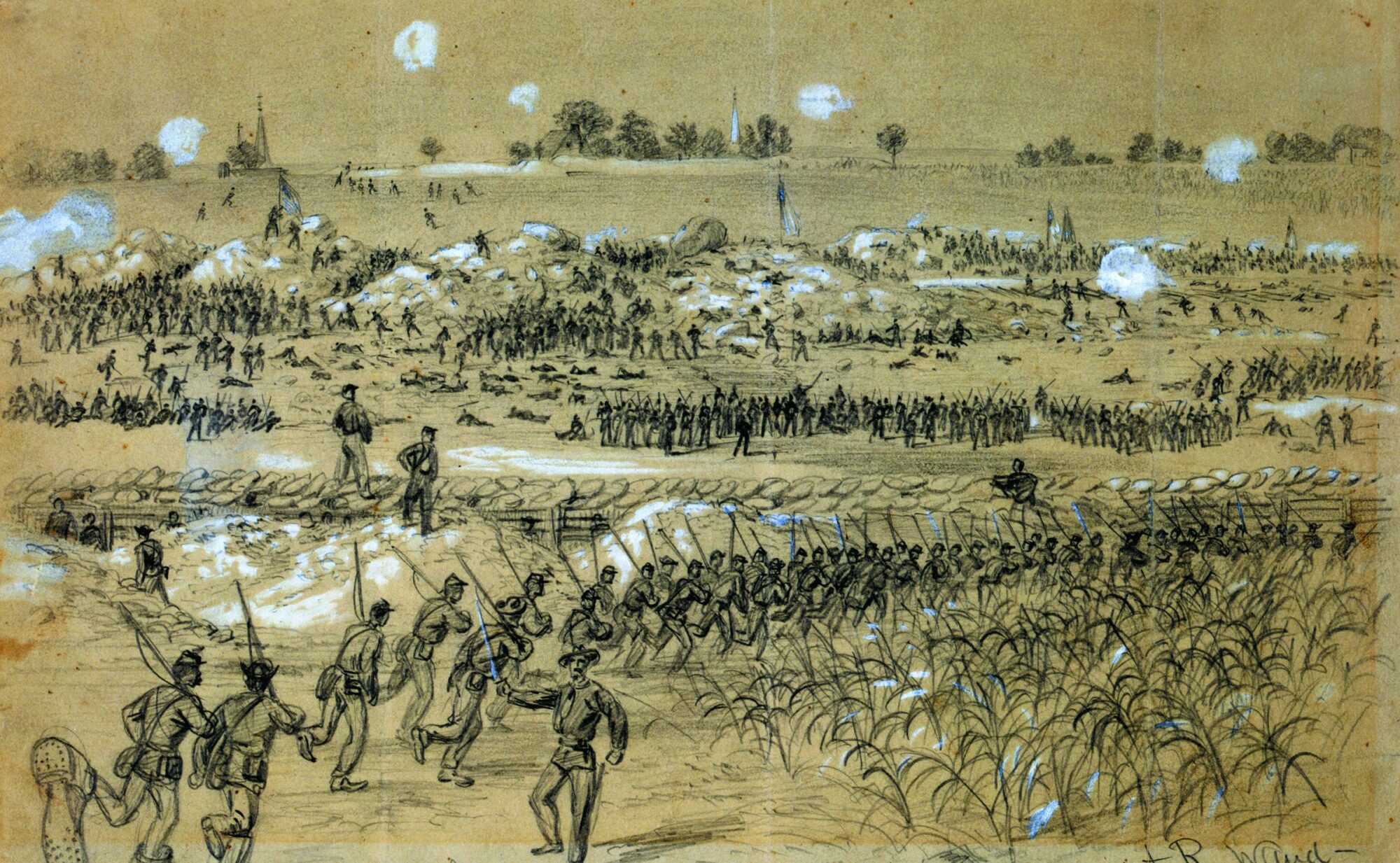

Pleasants had overheard one of his men talk about digging a tunnel to the Confederate lines at the shortest point between the two armies at Elliott’s Salient and blowing a gap in their defenses. The idea intrigued him and filled him with a new purpose in life. He soon brought it to Burnside for consideration. The ultimate outcome, however, would be one of the worst debacles of the entire conflict.

Pleasants had overheard one of his men talk about digging a tunnel to the Confederate lines at the shortest point between the two armies at Elliott’s Salient and blowing a gap in their defenses. The idea intrigued him and filled him with a new purpose in life. He soon brought it to Burnside for consideration. The ultimate outcome, however, would be one of the worst debacles of the entire conflict.

In his new book The Horrid Pit: The Battle of the Crater, The Civil War’s Cruelest Mission (Carroll & Graf, New York, New York, 2007, 284 pp., photographs, maps, index, $26.95, hardcover), author Alan Axelrod gives an in-depth look at the personalities involved in the planning, construction, and unfortunate outcome in what would be dubbed the Battle of the Crater.

Burnside was enthusiastic about Pleasants’s scheme and quickly informed Maj. Gen. George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, and Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, overall commander of the Union Army. Although Burnside envisioned the plan as a way to break the long siege, he also knew that if it was successful, it would help restore his reputation after the ill-fated “mud march” following the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862 and his lackluster performance at Spotsylvania Court House earlier in the year.

Neither Meade nor Grant was keen on digging a 500-foot tunnel toward the Rebel perimeter and igniting it, but they saw it as a way to keep the men occupied and out of the stifling heat of the Virginia sun. Both reluctantly gave the go-ahead but remained, as Axelrod points out, ambiguous in their orders to Burnside. For his part, Burnside drew up an elaborate attack plan that called for Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero’s 4th Division, which consisted of nine regiments of United States Colored Troops (USCT), to be the vanguard for the assault. They would reach the breach in the Confederate lines, fan out, and enlarge the opening, while several other divisions would follow and protect Ferrero’s flanks and drive toward Petersburg.

Meade and Grant were particularly wary of using black soldiers in combat. Until then, Ferrero’s men had been performing menial duties in the rear. Burnside pointed out, however, that his white troops were literally spent. Long, arduous months of combat had taken their toll and they were tired and in need of rest. Meade interceded and, backed by Grant, ordered a white division to lead the charge instead. Both men feared political repercussions from Washington if black soldiers were slaughtered indiscriminately.

Burnside had his remaining divisions draw straws to determine who would lead the attack. Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie’s 1st Division drew the short straw and was chosen. Ledlie, a coward and drunk, would later be relieved of command after it was discovered that he spent the entire battle in the rear with a bottle of rum for company while his troops were being massacred a few miles away.

In the predawn hours of July 30, after several attempts at igniting the fuses, explosives placed inside the mine were detonated. What followed would never be forgotten by eyewitnesses that day. “The air was filled with earth, cannon, caissons, sand-bags and living men, and with everything else within the exploded fort,” wrote one Union soldier. Ledlie’s division raced across toward the gap but, instead of moving around the massive crater, they took up positions within the depression, giving the Confederates time to regroup and counterattack. In the end, over 5,000 Union soldiers lost their lives, many of them USCT who were thrown into the fray after Ledlie’s men had become stalled at the crater.

Axelrod uses telegrams and actual excerpts from a court of inquiry that convened to investigate the action. Although Burnside, Ferrero, and Ledlie were censured, Meade escaped any imputation of wrongdoing for his part in interfering with Burnside. The USCT troops had trained prior to the battle and were eager to fight, while Ledlie’s troops were not familiar with their part in the initial assault. If they had kept advancing, the battle might have had a different outcome.

The Horrid Pit is a fascinating account of what transpired that sultry summer day in Petersburg in 1864, when a breakthrough Union victory might have been achieved. As Axelrod notes, “Instead of appreciating the power of moral hope, Grant and Meade recognized only the hazard of moral liability. The black men might win their freedom. But they might also lose their lives. That the men of the Fourth Division were willing to post their lives as collateral against the winning of their freedom counted for nothing. For the white commanders were not willing to let them make this bargain. They were guilty of a cowardice no military tribunal could prosecute, a terrible absence of faith and hope. And in this grievous lapse, a glorious victory was lost, cast away, with so many lives, into the horrid pit.”

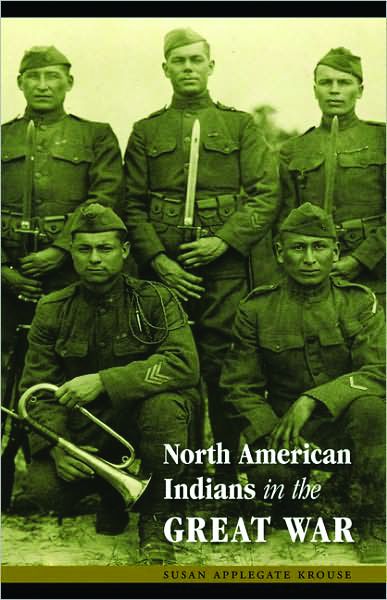

North American Indians in the Great War by Susan Applegate Krouse, University of Nebraska Press, Norman, OK, 2007, 250 pp., photographs, $45.00, index, hardcover.

North American Indians in the Great War by Susan Applegate Krouse, University of Nebraska Press, Norman, OK, 2007, 250 pp., photographs, $45.00, index, hardcover.

Inspired by the tireless work of Joseph K. Dixon, long an advocate for Native American rights, anthropologist Susan Krouse has compiled numerous firsthand accounts of Native Americans who served in World War I. These interviews were conducted by Dixon immediately following the conflict and offer the reader a glimpse into their service during that period. Dixon talked to an astonishing 25 percent of Native Americans who fought in the Great War and documented their stories. Sadly, he was never able to finish his work because of his death in 1926. Of the 12,000 Indians who joined the military, Dixon amassed over 2,800 questionnaires to document their service.

Dixon not only wanted to present an accurate portrait of the Indians’ participation during the war and their return to their homes, but his research also had an ulterior motive. He wanted to assist Native Americans in gaining citizenship, which, until that time, was not successful among the various tribes.

Native Americans performed admirably and at times heroically during World War I. Dixon noted that they wanted to “demonstrate their loyalty to the United States, as well as to their family traditions.” While both these reasons were true, Dixon’s fervent wish was that by demonstrating the Indians’ willingness to serve and even die for their country, it would bring about greater justice for their people.

Arthur Elm, an Oneida Indian from Wisconsin, served with the 1st Machine Gun Company, 127th Infantry, 32nd Division and saw extensive combat during the war. He told Dixon, “As I came into the port of New York on the ‘Antigone,’ a guy on the boat called out, ‘Who wants to re-enlist?’ He meant it as an insult to the Army. I felt it was a pretty dirty remark. He didn’t appreciate the kind of country he is living in, or the kind of country we have been fighting for.”

Dixon had planned to write a book entitled From Tepees to Trenches chronicling the sacrifices made by Native Americans in World War I. He wrote to a friend in 1920: “I want to place before the American people—in the form of a book—a complete story of the North American Indian in the War.” Although Dixon’s work would never come to fruition, Susan Applegate Krouse has done an admirable job of taking his monumental work and writing a wonderful account of Indian warriors in the Great War.

Rupert Red Two: A Fighter Pilot’s Life From Thunderbolts to Thunderchiefs by Jack Broughton, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2008, 352 pp., photos, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Rupert Red Two: A Fighter Pilot’s Life From Thunderbolts to Thunderchiefs by Jack Broughton, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2008, 352 pp., photos, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Colonel Jack Broughton compiled an incredible service during his three decades with the U.S. Air Force. He started his career after World War II and flew the last of the propeller-driven aircraft and witnessed the United States enter the jet age in the early 1950s. He saw extensive combat in the skies over Korea and Vietnam, flying hundreds of missions during both conflicts. He was awarded the Air Force Cross, two Silver Stars, four Distinguished Flying Crosses, and a host of other medals and decorations.

It wasn’t, however, until his retirement that Broughton began his career as a writer, relating personal experiences during his 30-year career, especially his time in Vietnam. Disgusted by the policies initiated by the Johnson administration, Broughton penned his first book, Thud Ridge, in 1969 in protest of the rules of engagement levied on him and his fellow pilots. He followed that book with Going Downtown about his experiences flying combat missions over North Vietnam.

An outspoken critic of politicians who needlessly place their armed forces in harm’s way, Broughton delivers his newest book in the same gutsy style as his previous two. As former Air Force Historian Richard P. Hallion writes, “Sit back and strap in—tight. You’re joining the U.S. Army Air Force at the end of the Big One. You’ll be passing from the era of the propeller-driven airplane to the era of the supersonic jet—You’ll love it!”

Sniper: A History of the U.S. Marksman by Martin Pegler, Osprey Publishing, New York, New York, 2007, 280 pp., photos, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Sniper: A History of the U.S. Marksman by Martin Pegler, Osprey Publishing, New York, New York, 2007, 280 pp., photos, index, $24.95, hardcover.

“It is a curious anomaly that the apogee of the 18th-century rifleman, the modern military sniper, has in very recent times suddenly emerged into the limelight from the outer fringes of warfare,” writes historian Martin Pegler in the introduction to his new book, Sniper. “The recent conflicts in the Gulf and Iraq have been called, with good reason, snipers’ wars and the snipers themselves have changed from being nobody’s children to the most sought after military specialists on the battlefield.”

Pegler’s statement is a far cry from the image of the skulking sniper, often thought of as a demented killer with a thirst for human blood. In reality, snipers are a dedicated, hard-working lot who undergo extensive training to become professionals at their trade. And work hard they must—one wrong move in combat could mean the difference between life and death.

Tracing the evolution of American snipers from the early colonial period to today’s recent conflicts in the Middle East, Pegler paints a new picture of the sniper. “None of us did it to be heroes or to get medals—a sniper with that attitude isn’t going to live long—we did it to make a difference,” writes Chuck Mawhinney, a USMC sniper during the Vietnam War. “I hope everybody reading this book will understand that, because it is a story that deserves to be told.”

Take Sides with the Truth: The Postwar Letters of John Singleton Mosby to Samuel F. Chapman edited by Peter A. Brown, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, 2007, 166 pp., index, $40.00, hardcover.

Take Sides with the Truth: The Postwar Letters of John Singleton Mosby to Samuel F. Chapman edited by Peter A. Brown, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, 2007, 166 pp., index, $40.00, hardcover.

Dubbed the “Gray Ghost,” John Singleton Mosby was a guerrilla fighter for the Confederacy during the Civil War. His lightning raids, often behind enemy lines, inflicted great damage on the Union forces. Although a brilliant leader, Mosby could prove to be a disturbing companion because of his obstinate attitude. Because of this, he had few close friends.

One individual did manage to get close to the moody Mosby, Samuel Chapman, a Baptist minister who served with him during the Civil War. After the conflict, Mosby and Chapman corresponded for years. From 1880 until 1916, the two former Rebels wrote numerous letters to each other; Mosby still referred to Chapman as “Captain.”

The letters offer an insight into Mosby’s character and honesty. He became an ardent Republican in a time when almost everyone in the South was a Democrat. He paid a high price for his political apostasy. His home was destroyed by fire and an attempt was made on his life. Despite this, Mosby remained adamant in his support of the Republican Party.

Mosby’s correspondence is interesting as history, and reveals another side to the man such as his surprising fear of being awakened in the night. He was always candid about his feelings toward others. He held great disdain for Union General Philip Sheridan, writing, “The truth is the records prove that Phil was a great liar or, according to his own statement, a murderer. I give him the benefit of the doubt & so he was a great liar.” Take Sides with the Truth should be on every Civil War buff’s bookshelf.

The Fall of Napoleon: Volume I, The Allied Invasion of France, 1813-1814 by Michael V. Leggiere, Cambridge University Press, New York, New York, 2007, 690 pp., maps, index, $40.00, hardcover.

The Fall of Napoleon: Volume I, The Allied Invasion of France, 1813-1814 by Michael V. Leggiere, Cambridge University Press, New York, New York, 2007, 690 pp., maps, index, $40.00, hardcover.

There has been a plethora of books on Napoleon Bonaparte. The strategies he employed are still taught at the top military institutions throughout the world, and his campaigns are studied by military historians and scholars alike. This rendition of the end of Napoleon’s career illustrates the massive allied effort to cross the Rhine River in the winter of 1813-1814 in an attempt to crush the French Army and force the “Little Corporal” to capitulate once and for all.

Leggiere does a masterful job at telling the story. Napoleon wanted his generals to defend the Rhine at all costs despite the weakened condition of their forces. His marshals did not agree with the emperor’s plan and sought to “trade land for time.” The combination of military and political intrigue ultimately would cause Napoleon’s downfall and his exile to Elba.

The author has done exhaustive research in writing the first volume of his proposed multi-volume work, and Napoleon aficionados are eagerly awaiting the next book in the set.

Charge! History’s Greatest Military Speeches edited by Congressman Steve Israel, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2007, photos, index, $32.95, hardcover.

There is no doubt that throughout history leaders have inspired their troops or countrymen with speeches that motivated them to winning a battle or even a war. In this latest book from the Naval Institute Press, New York Congressman Steve Israel has collected some of the most famous speeches and illustrates how they have inspired him as well.

From ancient times to present-day leaders, Israel has compiled the speeches in chronological order for the reader. Perhaps one of the most celebrated is British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s message to the country on June 4, 1940, urging its citizens to persevere: “Whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.” Churchill and his nation made good on that promise.

Bayonets for Hire: Mercenaries at War 1550-1789 by William Urban, Greenhill Books, St. Paul, MN, 2007, 304 pp., photos, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Bayonets for Hire: Mercenaries at War 1550-1789 by William Urban, Greenhill Books, St. Paul, MN, 2007, 304 pp., photos, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Since the beginning of recorded history, men have been enticed to join the army to fight for money, land, and other possessions. Given the name of mercenaries, these individuals have contributed much to victories on the battlefield since that time. But mercenaries have had a soiled reputation. Those fighting for mere materialistic gain, instead of their freedom or home, are considered by many unpatriotic. Yet without such men, battles and war cannot be won. The British Army during the American Revolution employed German-born Hessians, and some of those who defended the Alamo during the Texas War of Independence were lured to the Lone Star State with promises of land.

“I conclude that the age-old divergence of interest between civilian paymasters and professional fighting men, that gave mercenaries such a bad reputation, is still safely hidden, but may flare again into angry confrontation in time to come” writes William H. McNeill, professor of history emeritus at the University of Chicago. “For the age of mercenaries is not a thing of the past. It is instead a growing reality among us, not solely in the United States, but around the world.”

Rule Number Two: Lessons I Learned in a Combat Hospital by Dr. Heidi Squier Kraft, Little, Boston, MA, 2007, 243 pp., $23.99, hardcover.

One of the greatest tragedies of war is the fate of those who suffer long-lasting mental anguish from their participation in battle. In the Civil War, they named it the “soldier’s sickness”; in World War I it was dubbed “shell shock”; World War II saw it called “combat fatigue,” and Vietnam had the new phrase: “post-traumatic stress disorder.”

Whatever term is used, mental strain resulting from strenuous combat can cause severe depression that must be treated. Also, survivor’s guilt is another malady that can prove disastrous to servicemen. They often ask the question, “Why did I survive and my buddy get killed?”

Dr. Heidi Squier Kraft served for seven months with a U.S. Navy Surgical Team in 2004 to assist those suffering from such mental disorders. What makes her story even more heart-wrenching is the fact she had to leave her twin boy and girl behind during her stint in the Middle East. Since then she has left the Navy and works with the Combat Stress Control Program as its deputy coordinator. She still helps those who cannot forget the horrors of war.

The Road to Safwan: The 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry in the 1991 Persian Gulf War by Stephen A. Bourque and John W. Burdan III, Univer- sity of North Texas Press, Denton, TX, 2007, 312 pp., photos, maps, index, $27.95, hardcover.

The Road to Safwan: The 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry in the 1991 Persian Gulf War by Stephen A. Bourque and John W. Burdan III, Univer- sity of North Texas Press, Denton, TX, 2007, 312 pp., photos, maps, index, $27.95, hardcover.

Safwan is a city situated along the notorious “Highway of Death,” where coalition aircraft destroyed hundreds of Iraqi vehicles and armor during the first Persian Gulf War in 1991. General Norman Schwarzkopf, commanding general of the Coalition Forces, accepted the Iraqi surrender in Safwan.

The authors give a detailed account of the day-to-day combat by the 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry of the 1st Infantry Division. The “Big Red One” fought pitched battles with the elite Iraqi Republican Guard and helped pave the way for the surrender. The troopers also participated in Operation Norfolk, severing the Basra Highway and ultimately seizing Safwan Airfield.

This book is a tribute to the esprit de corps within the ranks of the unit. Despite the contention that the 1991 Gulf War was primarily a high-tech conflict, this account dispels that myth by relating the common soldiers’ story and their personal part in the sometimes horrific fighting.

Unlikely Heroes: Ordinary Men and Women Whose Courage Won the Revolution by Ron Carter, Shadow Mountain, Salt Lake City, UT, 2007, 254 pp., $21.95, hardcover.

Everyone knows the story of teacher Nathan Hale from Connecticut, a spy for the Americans during the Revolutionary War. He was caught by the British and eventually executed, but not before he uttered his famous last words: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.” There were, however, many other brave colonists, both male and female, who put their lives on the line to defend the emerging nation. In his new book, author Ron Carter profiles some of these lesser known personalities of that period in American history.

For example, Lydia Darragh, a Quaker woman who resided in Philadelphia when the British occupied the city in 1777, saved George Washington’s forces from certain destruction. She was fortunate to have a cousin was serving on the staff of British General William Howe, and this allowed her to remain in her home, with Howe merely requesting to occasionally hold meetings in her library.

It was during one of these meetings that Darragh hid in a linen closet and overheard them plan to ambush Washington as he moved his army from Whitemarsh to another location. Slipping away the next morning, she told an officer of the Continental Army, who quickly told Washington of the Redcoats’ plan. He changed routes accordingly. His army had been saved from annihilation by one brave and resourceful woman.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments