By Craig Van Vooren

Students of World War II know the name Percy Hobart—a British general who raised and trained several armored divisions and who invented all sorts of unique and unusual weapons of war—swimming tanks, flail tanks (for exploding landmines), a flame-throwing tank, a tank that laid down its own roadway, and many other odd-but-useful devices. The Germans had Alfred Becker, their own version of Percy Hobart.

Becker started the war as a senior noncommissioned officer in a Wehrmacht artillery regiment, and rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel commanding a unit that was a major factor in stopping Operation Goodwood in Normandy using guns that he built.

Alfred Becker was born in Krefield, Germany, located northwest of Düsseldorf, on August 20, 1899. He volunteered for service shortly after the beginning of World War I (at the age of 15) and ended the war as an artillery officer. He was awarded both the Iron Cross First and Second Class.

Following the war, he returned to Krefield and earned a degree as a mechanical engineer. He worked in the textile industry and became a part owner of Volkmann & Co. in Krefield and formed his own small manufacturing firm, Alfred Becker AG in Bielefield.

With the Second World War imminent, Becker was called up for active service on August 29, 1939, and was assigned to the 227th Infantry Division as a senior non-commissioned officer. The division did not participate in the Polish campaign and was stationed in Silesia guarding the western border.

During the next six months, Becker was promoted to first lieutenant and became the commander of the 12th Battery, a heavy howitzer battery with four 15cm howitzers, 185 men, and over 175 horses.

Becker’s first combat experience in World War II took place on May 10, 1940, with Germany’s invasion of France and the Low Countries; Becker’s unit engaged the Dutch Army. During this campaign, Becker came upon an abandoned Dutch mechanized artillery unit equipped with Brossel Tal artillery tractors. Becker replaced his horse-drawn equipment with the captured tractors, allowing his battery to be ahead of the rest of the division’s artillery regiment throughout the remainder of the campaign.

For his initiative and fearless conduct as a forward observer, Becker received the clasp to his Iron Cross Second Class and the clasp to the Iron Cross First Class.

While using artillery tractors improved the mobility of Becker’s battery, he felt that it still took too long to prepare the guns to go into action, so he conceived the idea of mounting artillery weapons on the vehicles directly, thus increasing their mobility immensely.

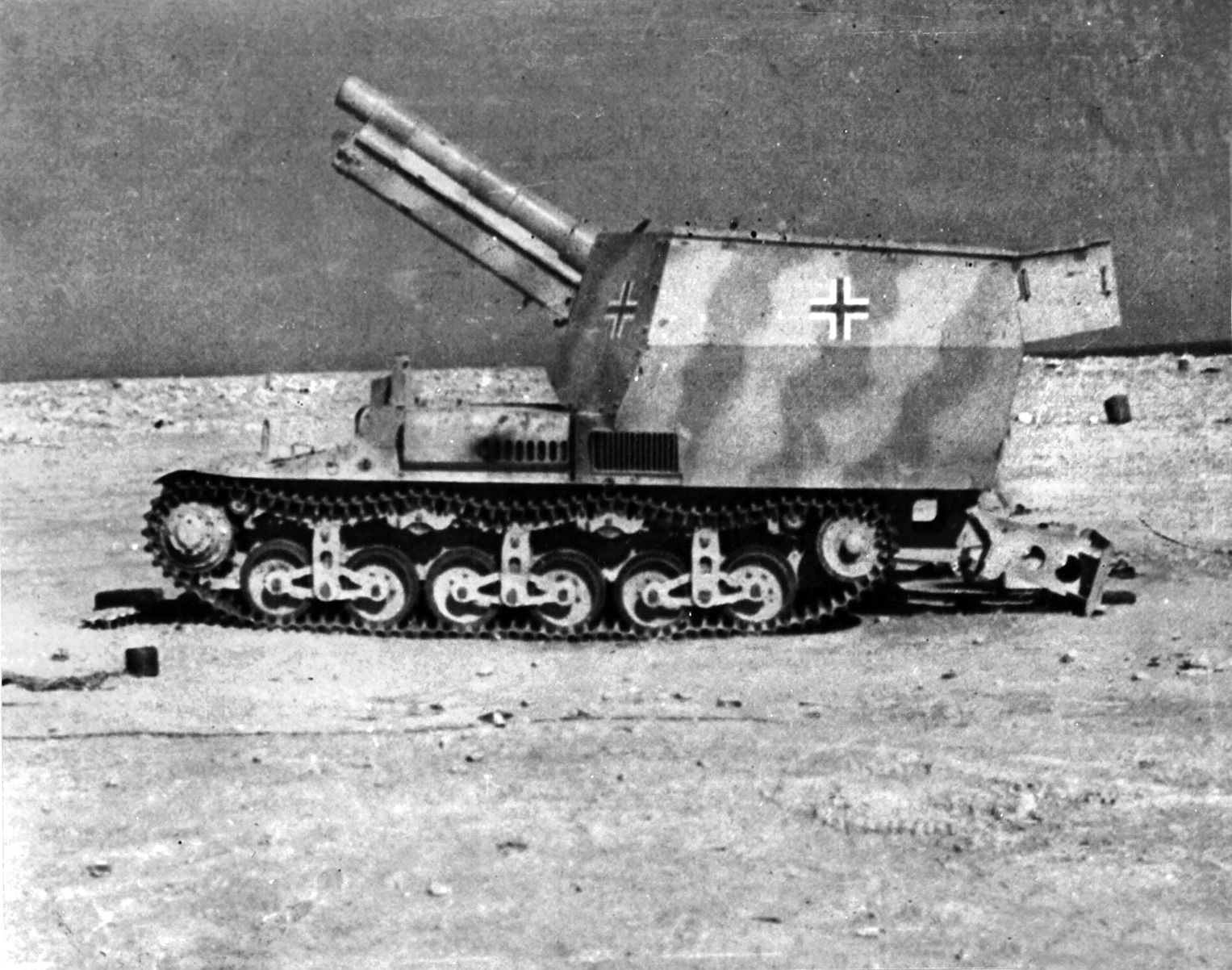

After the French campaign, Becker encountered many abandoned British Vickers Mk VI and VIb light tanks and converted these vehicles in self-propelled guns by mounting a 10.5cm howitzer at the rear of the vehicle with an armored combat compartment.

However, the recoil of the gun on such a light vehicle would cause the vehicle to move. Becker solved this problem by attaching a spade that could be lowered at the rear of the vehicle to absorb the recoil forces.

After testing a prototype vehicle in June 1941, Becker used his connections with manufacturers of stainless steel products in the Krefield area to procure armor plating. Becker’s men then built the final version of the self-propelled guns while they still performed their normal duties. The work was completed in July 1941 and the battery held a successful test firing at the Beverlo artillery range in Belgium.

In addition to the seven self-propelled guns, Becker’s staff also produced six artillery observation and communication vehicles, 12 ammunition carriers, and a maintenance vehicle using the Vickers Mk VI.

In October 1941, the 227th Infantry Division was transferred to the Eastern Front and assigned to Army Group North. It participated in the siege of Leningrad, and was assigned to positions in the forests south of Lake Ladoga. The unit was organized into three platoons of two guns each; the seventh gun was designated as a command vehicle.

It was at this time that Becker’s unit designation was changed to the 15th Battery. The unit was not deployed as a unified unit but was deployed with each platoon assigned to an infantry regiment within the 227th.

This battery of self-propelled guns was the first one within the German infantry artillery units. Panzer divisions and motorized infantry divisions relied on motorized artillery units while the infantry divisions relied on horse drawn artillery. Both required that the gun crews prepare the site before the guns could be brought into action. However, Becker’s battery could drive to a location and almost immediately start firing. German commanders quickly recognized this huge advantage and came to depend on the battery to act in a “fire brigade” role, quickly transferring it to areas needing artillery support.

Beginning in mid-October 1941, Becker’s battery was continually in action, supporting not only the 227th, but other divisions as well. This situation continued through the winter.

But these actions exposed problems. These guns were meant to provide indirect fire support, but the vehicles were often used in direct fire support of the infantry, a role to which they were not suited. In February 1942, three guns were lost in a battle where they tried to engage Russian KV-1 tanks with direct fire. The guns’ armor-piercing rounds could not penetrate the Russian tanks’ armor.

Becker’s four remaining vehicles continued to provide support to the infantry units fighting around Leningrad through the spring of 1942. They continued to suffer losses due to providing close support; the last gun was destroyed in late spring/summer 1942.

The German units supported by Becker’s vehicles praised their performance. The guns’ chassis were found to be reliable and capable of being used in extreme conditions. The vehicles’ low fuel consumption was also viewed as an asset.

Becker was wounded twice while in Russia, the first time in October 1941, and his actions during this campaign earned him the German Cross in Gold, presented to him on May 13, 1942. Becker was also promoted at this time to the rank of captain.

The glowing reports of “Becker’s Battery” in Russia attracted the attention of the OKH (German Army High Command). As a result, Becker was recalled from the Eastern Front and assigned to work with Alkett, a major German manufacturer of armored vehicles, to modify obsolete French equipment into useful fighting vehicles.

He first focused on the Lorraine 37L, known to Germans as the Lorraine Schlepper. Similar to the Vickers Mark VI, the driver was at the front of the vehicle while the engine was located in the middle, allowing an armored compartment for the gun and crew to be built at the rear.

These reports also came to the attention of Adolf Hitler, who requested a demonstration, which was held on May 23, 1942. Hitler was pleased and expressed his support for the type of weapons demonstrated—and was amazed that they had been built by troops in the field. He saw this as an opportunity to improve the effectiveness of his troops for minimal cost.

Hitler was aware that the Germans had captured vast quantities of French armored vehicles two years earlier, but were not able to use them because the French vehicles did not lend themselves to German tactics.

Hitler directed that all of the currently available Lorraine Schleppers be made into self-propelled guns, mounting either a 7.5cm anti-tank gun, a 10.5cm howitzer, or 15cm howitzer. He further ordered that 30 of the vehicles mounting 15cm guns be built by the end of June for shipment to Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps. Becker continued to work with Alkett to construct these initial 30 vehicles, which were completed in July 1942.

Becker then received a commission from Hitler through Reich Armaments Minister Albert Speer to return to France with following tasks: 1) take an inventory of all remaining captured British and French armored vehicles; 2) determine which vehicles were useful; and 3) collect the vehicles and convert them as necessary. The order required Becker to create enough usable equipment to equip “at least” two panzer divisions.

The order was enormous and to carry it out required personnel that had metalworking skills. Fortunately, Becker knew of a group of men with whom he had prior experience—the men of his old battery. Becker could provide instructions to these men with confidence that they would successfully complete the tasks. With the destruction of their artillery pieces during combat around the Leningrad area, they had been sent to infantry units.

Strict German Army regulations forbade the transfer of able-bodied soldiers from the Eastern Front back to France. To bypass these regulations, Becker worked out a deal with Maj. Gen. Friedrich von Scotti, commander of the 227th Infantry Division. The commander would send 10 soldiers a week back to Germany for rest and recreation. However, instead of reporting back to the 227th, the men would instead report to Becker’s unit in France. This allowed Becker to transfer the majority of his old unit back to France by the end of 1942. In return, Becker sent 20 armored vehicles to the 227th Infantry Division.

Becker established his headquarters (Baukommando Becker) at Maisons-Laffitte, on the northern outskirts of Paris. His command utilized three former French automobile factories: Matford, Talbot, and Hotchkiss, all near Paris.

Becker sent his men out throughout the French countryside to retrieve every French vehicle, no matter its condition, and bring it back to the collection site at the Hotchkiss factory. There, Becker’s staff would determine whether to scrap the vehicle or to use it. All useful parts were removed from scrapped vehicles.

Becker’s production process was simple: his unit would produce a prototype using plywood, which was then used as templates to construct the armored superstructures. The vehicles were then produced in batches primarily by Becker’s staff, but at times by French workers under the supervision of skilled group leaders from Becker’s staff.

For his work at Alkett and Baukommando Becker, Becker was awarded the War Merit Cross First Class with Swords on September 1, 1942.

In 1942, Germany was concerned about an invasion of German-occupied France from Britain. To counter this, they planned to develop a highly mechanized army that could rapidly be deployed; the “Schnelle Brigade West” was one of the units developed. Colonel Edgar Feuchtinger was assigned as the commander of the unit. He previously commanded Artillery Regiment 227, Becker’s old unit.

Feuchtinger was ordered to continue to strengthen the Schnelle Brigade West. However, he was unable to use standard German equipment to do this since all of that was earmarked for the other operational areas. So he worked with Becker to provide the vehicles needed.

At this time, Becker was appointed the commander of Gepanzerte Artillerie Abteilung (Sfl.) z.b.V., which was part of Schnelle Brigade West. He had to not only oversee the construction of vehicles for the Wehrmacht, but he was required also to organize and train a combat unit. The men who were assigned to his construction command also were incorporated into this unit.

On May 6, 1943, Hitler ordered that the 21st Panzer Division be reactivated after its loss in North Africa. On June 27, OKH ordered Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt to upgrade Schnelle Brigade West to a panzer division and designate it the 21st Panzer Division (New). An important provision in this order was that no German equipment would be assigned to the division, with the exception of communications equipment and a dozen 8.8cm Flak guns; Colonel Feuchtinger would have to make do with material from captured stocks.

The equipment restriction meant that the 21st Panzer Division had to rely on Baukommando Becker for much of its equipment. Becker’s unit delivered over 550 armored vehicles to the Wehrmacht, with over 400 going to the 21st Panzer Division. These vehicles basically provided the mobile armored resources for the division’s panzergrenadier regiments, the artillery regiment, the combat engineer regiment, and the communication section, as well as Becker’s own unit, Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200.

During this time, Becker was promoted to major.

Becker’s unit was unique within the organizational structure of a panzer division. Becker described his unit as being a trial unit with the purpose of obtaining concentrated fire while in action. Each battery was furnished with six 7.5cm guns for direct fire and four 10.5 cm guns for direct and indirect fire. The latter guns were positioned 500-1,000 kilometers behind the 7.5 anti-tank guns. All guns of the battery would be directed by radio by the battery commander from his scout vehicle, located in a forward position.

The radios were of the latest design and allowed the operators to escape detection because they used very low frequencies that were not scanned by the Allies. Their range was limited, though, requiring that messages be relayed through many tanks. This organization was made to alleviate the weak anti-tank capability of Becker’s assault artillery battery displayed in Russia.

By June 1, 1944, Becker’s unit was organized into five batteries. The first four had four anti-tank guns and six howitzers each while the fifth battery had only two anti-tank guns and four howitzers. The headquarters company was assigned one anti-tank gun and six flak guns.

At that time, the elements of Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200 were stationed near Caen in Normandy with Batteries 1 through 4 stationed near Cagny, southeast of Caen and east of the Orne River, and Battery 5 in training north of Caen, near Epron and west of the Orne River.

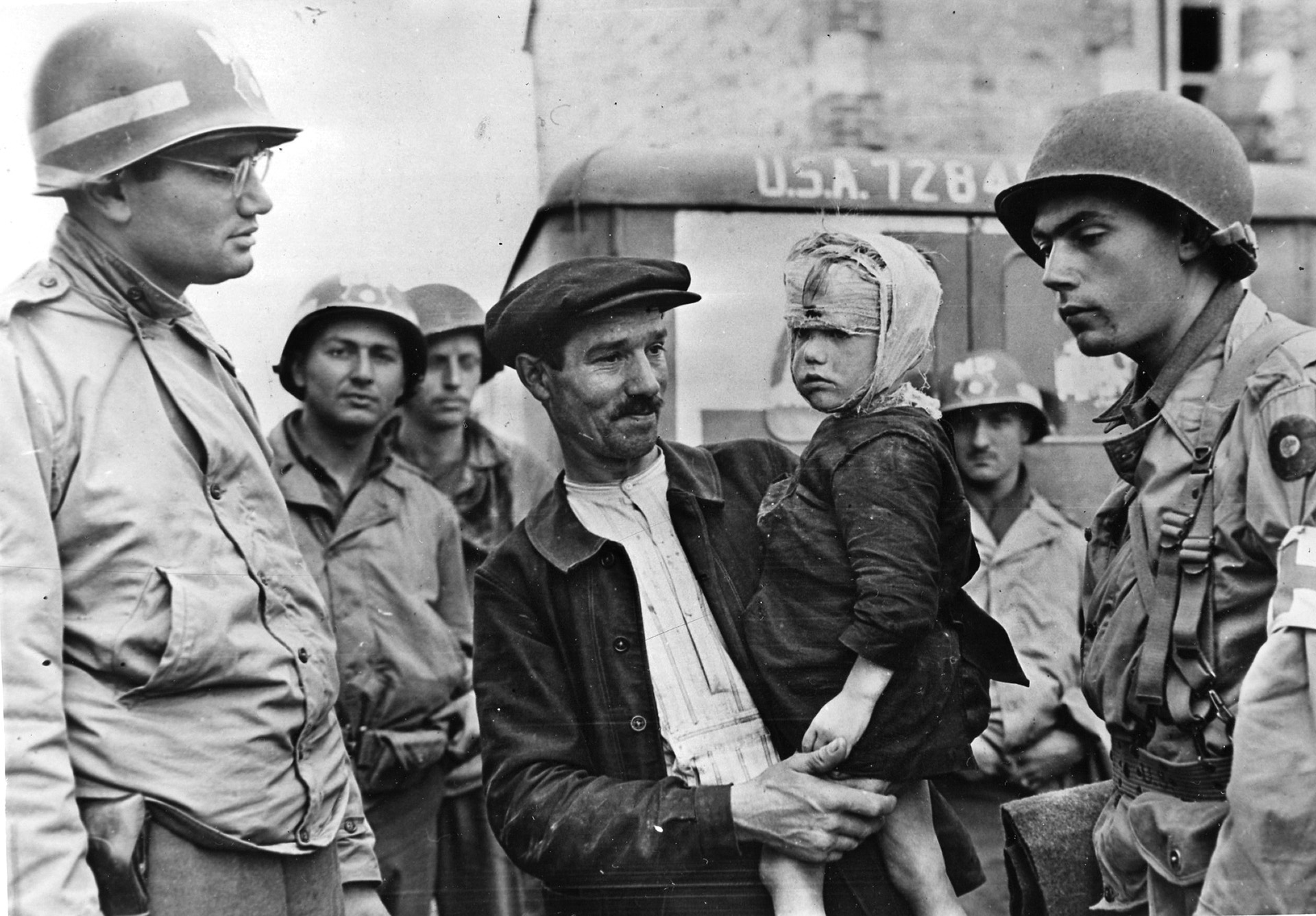

On June 6, the Allies launched Operation Overlord, the cross-Channel invasion of Normandy. Becker’s unit was placed on alert at 2 a.m. At 10 a.m., Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200 was ordered to support the German counterattack on Benouville (the site of Pegasus Bridge, captured by British glider forces), on the west side of the Orne River. This required most of the unit to go through the bombed-out remains of Caen; the fifth battery was to join them there.

Half of the unit had crossed the bridge into Caen when new orders arrived telling them to turn around and support Panzergrenadier Regiment 125 east of the Orne River; the unit did not arrive in its new position until nightfall. Thus, Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200 did not fire a shot until the night of June 6.

Becker’s unit supported Panzergrenadier Regiment 125 for the next six weeks, and Becker managed to keep the losses of men and vehicles to a minimum. During this time his unit claimed to have destroyed at least 21 Sherman tanks and captured two more.

By the middle of July, the Allies had been battling the Germans in Normandy for six weeks, but had, as yet, been unable to break out of the invasion bridgehead. Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery ordered plans be developed for a new operation, called “Goodwood,” with the British attack force consisting of three armored divisions (the 11th Armoured Division, the Guards Armoured Division, and the 7th Armoured Division) totaling over 900 tanks.

Monty’s plan called for 11th Armoured to attack first from Hérouvillette, with the objectives of screening Cagny on the left flank and capturing the villages of Bras, Hubert-Folie, Verrières, and Fontenay-le-Marmion on the right. The Guards Armoured Division would then follow and capture Cagny and Vimont. The 7th Armoured—the “Desert Rats”—would advance last and would move south of the Garcelles-Secqueville ridge, with the ultimate objective of Falaise. British and Canadian infantry would attack to protect the flanks of the armored assault.

The British began staging these divisions into the Orne bridgehead on the night of July 16/17 in an attempt to mask the British intentions. But German observers spotted the preparations and alerted Rommel’s headquarters, which sent out an alert for a counterattack starting on July 17.

The German forces defending this area of battlefield consist of the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division and 21st Panzer Division, both under the command of Lt. Col. Hans von Luck, commander of Panzergrenadier Regiment 125.

Becker was in the field, north of Cagny, at 4:30 a.m. on July 18 in his armored scout vehicle. He was located between his third and fourth batteries and was in touch with his mobile command post. He had positioned his batteries as follows: Battery 1, commanded by Captain Eichorn, was located on the northeastern side of Demouville: Battery 2, commanded by Captain Foerster, was on northern end of Giberville; Battery 3, commanded by Captain Noesser, was located in Grentheville; Battery 4, commanded by Captain Roepke, was located on eastern side of Le Mensil Frementel; and Battery 5, commanded by 1st Lt. Schreiner, was located near Le Prieure.

Operation Goodwood opened with the most concentrated aerial bombardment of the war for a ground operation. At 5:35 a.m., the complex aerial bombardment began and lasted for over two hours. Bombers from the RAF Bomber Command, the U.S. Eighth Air Force, and the U.S. Ninth Air Force dropped over 8,500 tons of bombs on German positions all over the battlefield.

The effects of the bombing were devastating for the Germans. Those not killed or wounded were incapacitated and surrendered to the advancing tanks. Perhaps the most serious result to the Germans was the loss of their tanks. Panzer Regiment 22 and Schwere Panzer Abteilung 503 were positioned close to the front line and were devastated by the bombing. Those tanks not destroyed required considerable work to become operational again.

This was difficult since the bombing wiped out maintenance facilities accompanying the tanks. Luck’s anti-tank capability on his right flank was reduced to a few anti-tank guns and Becker’s batteries.

The air bombardment also impacted some of Becker’s batteries. When it began, Becker realized that an attack was imminent. His primary focus was to keep in contact with Eichorn’s battery since that battery appeared to be the one that would be closest to the route of the attack.

However, Becker lost contact with Eichorn around 7 a.m. as a result of the American air bombardment. He heard nothing more from Eichorn until later that morning when the captain reported to Becker at his command bunker that all his armored fighting vehicles were lost due to the bombing. Only his command vehicle, which was located forward of the battery position, survived the aerial assault.

The second battery sustained some damage, with two anti-tank guns being immobilized. Becker also had trouble maintaining contact with this battery initially.

Following the air bombardment, the British tanks of the 11th Guards Division started to advance behind a rolling artillery barrage. The first unit to advance was the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Tank Regiment (RTR), heading to west of Grentheville and advancing to the Bourgesbus ridge.

By 8:45 a.m. the tanks had reached the Caen-Troarn railway line. While the tanks were able to cross the line easily, their supporting vehicles were bunching up because they required a level crossing, which resulted in some units being unable to keep up with rolling barrage. Still, the advance was going forward with few difficulties.

After the tanks crossed the railway line, they then veered southwest to the Caen-Vimont railway line and then the Bourgebois ridge.

The next tank unit to advance was the 11th Guards’ 2nd Fife and Forfar Yeomanry. Its objective was to advance east of Grentheville and on to Soliers, but its drive was held up at the Caen-Troarn railway line waiting for RTR to cross. As a result, they, too, could not keep up with the rolling barrage.

Finally, the tanks of the 23rd Hussars started to advance. Despite the delays, the attack seemed to be going well.

The initial German response to Goodwood was confused. The 3rd Battalion of the RTR was able to advance across the Caen-Troarn railway line, through the 2,000-yard corridor between Demouville and Sonnerville in the German lines, and then the Caen-Vimont railway line without encountering any resistance; the defenders were just emerging from their bombardment shelters, and there was so much dust in the air, the German defenders could not see the tanks. The following tanks were not so lucky.

At around 9 a.m., Lt. Col. Luck arrived at his command post at Frenouville, returning from leave in Paris. He quickly became aware of the British attack; climbing into his command tank to reconnoiter the battlefield, he was horrified when he got Cagny to see that 40-50 tanks were crossing the Caen-Vimont railway west of Cagny. Luck was then informed that his tanks were either destroyed or inoperable.

While in Cagny, Luck discovered a Luftwaffe flak battery and commanded it to fire on the second wave of British tanks. Shortly thereafter, the first tanks from the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry tried to cross the Caen-Troarn railway and four Shermans were quickly set ablaze. Twelve more tanks were soon knocked out from the concentrated fire from this battery and from Becker’s third and fourth batteries.

Luck then returned to his command post to find Becker already there. The major informed him that his first battery at Demouville had been destroyed and that the second battery at Giberville had sustained damage but was still operational. The other three batteries were intact.

Becker now began to move his batteries to provide vital anti-tank defense. These movements were undertaken as a series of position changes that allowed the Germans to ambush the British tanks and then move to another location and set up another ambush.

The second battery moved to new positions south of the Caen-Troarn railway. It withdrew through the tunnels of the Caen-Dozule railway and eventually took up positions near Hubert-Folie. Here, it still supported the defenders of Giberville, but the battery’s retreat under pressure allowed the British to capture Giberville.

Meanwhile, the third battery remained in Grentheville. Because the British attacked using tanks without infantry support, they were forced to bypass Grentheville on both the west and east sides; the third battery hit the tanks on both sides. At approximately 3 p.m., the battery abandoned Grentheville and relocated to positions south of Soliers.

The fourth battery initially offered resistance to tanks of the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry that were trying to cross the Caen-Troarn railway but lost a 10.5cm gun to the heavy British artillery bombardment. The battery was then forced to withdraw and take up new positions.

The fifth battery provided artillery support to the 2nd Battalion, Panzergrenadier Regiment 125, as they resisted the advance of the British infantry attacking Touffreville. Before Le Priere could be captured, the battery withdrew to new positions near Le Poirier.

The resistance put forth by Becker’s batteries was crucial to the German defensive measures in that it allowed the Germans time to bring up reinforcements. The first reinforcements were the tanks of the Panther Abteilung of SS Panzer Regiment 1. These were followed by the troops of 2nd and 3rd battalions of SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 2. The Panther tanks, together with 3rd and 5th Batteries, repulsed an attack of the 23rd Hussars east of Soliers; elements of the 12th SS Panzer Division arrived later in the afternoon.

Effectively, the British attack had stalled by this point and there was to be no breakthrough; the British withdrew their forces to the Caen-Vimont railway line to reorganize them. The Germans had contained the advance while inflicting severe losses on the attackers. The 11th Armoured Division, which led the attack, had lost 126 tanks by the end of the July 18. It must be remembered that this was done without the initial use of the Germans’ primary weapon, its armor, which was rendered inoperable by the British aerial bombardment.

The arrival of German reinforcements allowed the 21st Panzer Division to be relieved. Late in the afternoon, the 3rd Battery moved from Soliers and joined forces with the 2nd Battery near La Hogue. The next day, Becker’s batteries fought in the area from Frenouville to Bourgbus, and that night Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200 was replaced by other units and ordered to go to positions around Troarn.

Goodwood would continue for the next day and a half. On July 20, inclement weather deprived the Allies of their air superiority, forcing Montgomery to halt Goodwood.

The failure of Operation Goodwood to break out resulted in Montgomery having to do damage control. He later stated that the operation was not to break out but to tie down the German armor. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was very unhappy with gains achieved versus the amount of material expended and losses incurred. There was talk of replacing Montgomery, but that talk vanished with success of the American Army’s Operation Cobra.

The 21st Panzer Division, which had been fighting for over six weeks, was ordered to be relieved by the 272nd Infantry Division on July 27, although parts of the division, including Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200, were placed under the command of the 272nd Infantry Division. This respite was short-lived.

On July 30, Montgomery initiated Operation Bluecoat to create another hotspot that required a German response. He chose the area where there was little German armor—on the western flank of his army south of Caumont and west of Villers Bocage. He moved the armored divisions that were involved in Goodwood from the Orne bridgehead south and east of Caen to this western sector.

Operation Bluecoat commenced 6 a.m. with carpet bombing of selected targets and an artillery barrage. The British ground troops then advanced. At first, the German line held, but soon breakthroughs were being made in the German defenses. Panzergruppe West committed the 21st Panzer Division to the battle at 4 p.m. on July 30, and Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200 was ordered to new positions south of St. Martin. The unit would not reach its position until the next afternoon.

Part of Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200 was used to help secure areas south of St. Martin and the rest of the unit assisted in securing areas southeast of the Foret l’Eveque. Soon after arriving, the unit was drawn into combat. The Guards Armoured Division was ordered to advance through St. Martin towards the village of Le Tourneur. Parts of the division suddenly appeared in the evening south of St. Martin before Hills 192 and 238.

Resisting their advance were elements of the German 326th Infantry Division, Feld-Ersatz Battalion 200, and Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200. Heavy fighting ensued, with Hill 192 and the village of Le Val changing hands several times.

Meanwhile, a more serious threat was developing for the Germans. A British reconnaissance unit advanced through a gap in the German lines, finding an unguarded bridge over the Souleuvre River and taking possession of it. They reported this success at 10:30 a.m. The 11th Armoured rushed to exploit this opportunity.

Six Cromwell tanks moved through the Foret l’Eveque towards the bridge. A fight ensued between these tanks and self-propelled guns from Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200 which had just arrived. Tanks from the 23rd Hussars soon followed and joined in the battle; British infantry finally secured the bridge at 8 p.m. The 1st Battalion of Panzergrenadier Regiment 125 was brought up to cover the Germans’ exposed left flank, allowing the Germans to temporarily stabilize their front.

After this, Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200 continued to support Panzergrenadier Regiment 125 through the first three weeks of August, sustaining heavy losses in the process. By August 19, Feuchtinger reports that Becker’s unit had only four assault guns remaining. Becker and his men were now involved in the battle of the Falaise Pocket. Becker and some of his men were able to escape the deadly pocket, but just barely.

After the battle of the Falaise Pocket, Becker initially established his headquarters in Belgium at Fosses la Ville in the castle of Taravisee; on September 3, he moved the headquarters due to the American advance. At this time, he and his surviving men began to reconstitute the

Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200 by creating more vehicles. On October 1, 1944, the 21st Panzer Division reported that Becker’s unit has six 7.5cm Pak 40 vehicles mounted on the Hotchkiss chassis.

During October 1944, Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200 was detached from the 21st Panzer-Division. At the end of November, Sturmgeschütz Abteilung 200 was reorganized into a standard assault-gun battalion with 22 Sturmgeschütz III (a fully tracked assault gun) and nine Sturmhaubitze (a version of the assault gun, armed with a 105mm light field howitzer). The six Hotchkiss anti-tank guns were transferred to Panzerjäger Abteilung 200 in the 21st Panzer Division.

During this time, Becker received his final commendations. On October 24, 1944, he received the Wound Badge in Silver for being wounded the fourth time in the war on August 1, 1944. On July 2, 1944, the 21st Panzer Division recommended Major Becker for the Knight’s Cross of the War Merit Cross with Swords. It is not clear when he received this award as the original request was lost and had to be resubmitted in November. During this time he was also promoted to lieutenant colonel.

Alfred Becker was captured by the Allies in December 1944. He was released weeks after Germany surrendered in 1945, and asked the British authorities overseeing Krefeld for permission to reopen his textile plant. Permission was granted due to his outstanding war record and his treatment of French workers who worked at Baukommando Becker. The company is still run as a family-owned business today.

Becker kept extensive records concerning his experiences and projects during the war. In 1979, the British Ministry of Defense produced a training film concerning Operation Goodwood. They made use of these records and mentioned Becker and his unit extensively in the film. The film highlights how an inferior force can use defensive tactics and innovative weapons to thwart a much larger attacking force.

Alfred Becker died on December 26, 1981.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments