By Al Hemingway

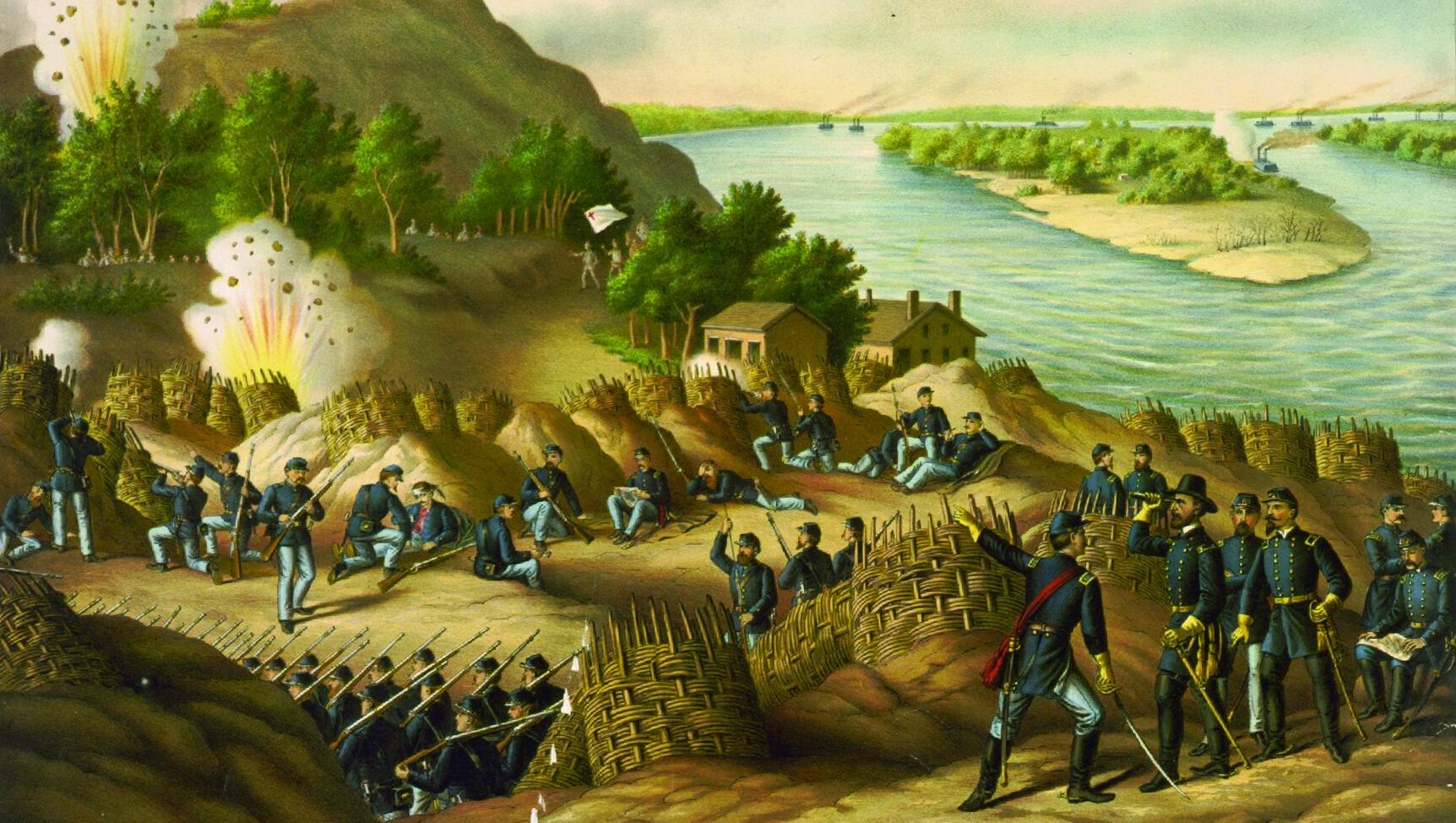

By mid-1862, despite the humiliating Union defeats in the East, the Civil War in the western theater was gaining momentum. Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, commanding the Army of the Tennessee, had achieved impressive victories at Forts Henry and Donelson. After an initial setback at Shiloh, Grant’s army had regrouped and defeated the Confederates by a narrow margin in the blood iest battle of the war thus far.

Since the very outbreak of the conflict, Union forces had desperately wanted to seize control of the Mississippi River. With the fall of New Orleans and Memphis, the only city blocking such control was Vicksburg, Mississippi. The port city, situated where the Yazoo and Mississippi Rivers meet, was the key to controlling the entire 2,300-mile waterway and choking off supplies to the Confederate armies in the field. Grant was determined to turn the key in the lock and open or close the door, depending on who was doing the knocking.

Since the very outbreak of the conflict, Union forces had desperately wanted to seize control of the Mississippi River. With the fall of New Orleans and Memphis, the only city blocking such control was Vicksburg, Mississippi. The port city, situated where the Yazoo and Mississippi Rivers meet, was the key to controlling the entire 2,300-mile waterway and choking off supplies to the Confederate armies in the field. Grant was determined to turn the key in the lock and open or close the door, depending on who was doing the knocking.

In his latest offering, Vicksburg 1863 (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2009, 496 pp., notes, index, photos, maps, $30, hardcover), novelist-turned-historian Winston Groom offers a characteristically detailed account of the events leading up to the siege and its aftermath. In addition to the battles and skirmishes that led to the eventual capitulation of Vicksburg, Groom delves into the many personalities on both sides, and how their actions and petty jealousies affected the outcome, inevitable as it now may seem.

With the capture of New Orleans, the citizens of Vicksburg realized with horror that the war was at their own doorstep. Pennsylvania-born General John C. Pemberton, head of the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana, immediately ordered the city fortified for the inevitable Union attack. Pemberton was caught between two factions—those of President Jefferson Davis and General Joseph E. Johnston—both of whom were his superiors and each of whom had different ideas about how to hold the city. This friction, coupled with a glaring lack of communication between all parties, would be one of the main reasons why Pemberton ultimately failed in his task. Like many Civil War generals, Pemberton would prove to be a better paper shuffler than field commander.

Initially, Federal gunboats attempted to shell the “Gibraltar of the West” into quick submission. Led by Rear Admiral David Farragut, the Union flotilla, accompanied by a sizable infantry contingent, failed in its first attempt to force Vicksburg’s surrender. Besides contending with supply problems, Confederate snipers, and the multitude of sandbars that made navigating the river an ongoing nightmare, Farragut did not realize that his overly ambitious foster brother, Commander David Dixon Porter, was bad-mouthing him to his superiors in Washington. Luckily for Farragut, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles disliked Porter, who he said dryly was “given to exaggeration in relation to himself.”

Meanwhile, the relentless Grant rolled up some important victories as he inched his way ever closer to Vicksburg. The battles at Raymond, Jackson, and Champion’s Hill were costly for the Confederacy, although Brig. Gens. Earl Van Dorn (later killed by a jealous husband) and Nathan Bedford Forrest conducted a devastating raid on the Union supply depot at Holly Springs, destroying everything in sight.

After several unsuccessful assaults on the city, Grant settled in for a protracted siege. From late May until July 4, 1863, residents endured numerous hardships. Kate Stone, who lived just north of the city, kept a journal that has since been indispensable to historians. In it, she described the day-to-day life of the population and army as they battled starvation, disease, and constant shelling from Union gunboats.

On the 87th birthday of the United States, Pemberton tendered his sword to Grant, signaling the end of the siege. Some 9,000 Union soldiers and 10,000 Confederates had become casualties during the campaign. On July 9, the garrison at Port Gibson also surrendered. These two triumphs gave the Union complete control of the Mississippi River and put two more sizable nails in the Confederate coffin.

Target Patton: The Plot to Assassinate General George S. Patton by Robert Wilcox, Regenery Publishers, Washington, D.C., 2008, illustrations, index, notes, $27.95, hardcover.

Target Patton: The Plot to Assassinate General George S. Patton by Robert Wilcox, Regenery Publishers, Washington, D.C., 2008, illustrations, index, notes, $27.95, hardcover.

The untimely death of American general George S. Patton in December 1945 has always been shrouded in mystery. Many have wondered whether the often outspoken commander died as a result of a traffic accident that cold, blustery day in Germany, or was assassinated. If the latter were true, what was the reason that drove an individual or individuals to kill him?

In his latest book, Robert Wilcox makes a convincing argument that there were various factions that wanted Patton eliminated. Patton had said, in no uncertain terms, that he did not like or trust America’s erstwhile Russian allies. He advocated stopping the Red Army, by any means possible, from gobbling up Eastern Europe. Patton’s Third Army, he felt, could easily halt the Russian advance. U.S. officials, from President Harry Truman down, did not want to incite a war with the enormous nation that had been a vital if troublesome partner in defeating the Axis powers. Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin hated Patton on sight and made it clear in the highest circles that he wanted him silenced.

But did the United States government acquiesce to such an agreement and make a pact with the devil, so to speak, and kill Patton? Wilcox includes lengthy interviews and acquired the notebooks of an OSS operative named Douglas Bazata, a former Marine and member of the famous Jedburgh group in World War II that had operated behind German lines.

Bazata claimed that he was asked by OSS head William “Wild Bill” Donovan to assassinate Patton. Such an explosive charge was never proved, although Bazata did pass a lie detector test. Despite the nasty gash on his head that Patton received in a collision between his staff car and another vehicle, the general seemed to be responding to treatment in the hospital and, at one point was even considered ready for release. Suddenly, the 60-year-old general officer took a turn for the worse and died from an embolism, or lack of blood flow in an artery, usually caused by a clot. Was this the real cause of death or, as Wilcox suggests, had a Russian agent administered a drug to make it seem like Patton died from natural causes?

To this day, no concrete evidence exists to prove definitely that Patton was murdered. However, many questions remain unanswered. Documents went missing, witnesses disappeared, and even Patton’s 1938 Cadillac, currently on display in the Patton Museum of Cavalry and Armor at Fort Knox, Kentucky, may not, in fact, be the authentic vehicle he was riding in that fateful day.

Wilcox’s account is intriguing, if not definitive. He presents sound evidence suggesting that Patton indeed may have been the victim of an assassination plot. It reads like a James Bond novel, but in this case, the characters are all too real and the ending all too tragic.

John Paul Jones: Maverick Hero by Frank Walker, Casemate, Philadelphia, PA, 2008, 278 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover.

John Paul Jones: Maverick Hero by Frank Walker, Casemate, Philadelphia, PA, 2008, 278 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover.

To every student of history, the immortal words “I have just yet begun to fight!” uttered by Captain John Paul Jones were shining inspirations to the fledgling American colonies to continue their fight for liberty and freedom from the oppressive British government during the American Revolution.

But what kind of man was the real John Paul Jones? Small in stature, he was an extremely complex individual. On the one hand he could be charming and gracious, especially to women. On the other, he could be a cruel and despotic naval commander who drove his men beyond their limits—so cruel, in fact, that during one voyage his own crew plotted to toss him overboard.

His unpredictable dual personality aside, Jones was inarguably the father of the American Navy. The sea battle between the Bonhomme Richard and the 50-gun British frigate Serapis was the longest ship-to-ship engagement in British naval history. It was during that battle that Jones yelled his now-famous phrase to Captain Richard Pearson, earning him a timeless place of honor in American naval history.

When the Americans finally won their independence, the U.S. Navy was disbanded and Jones set out for Russia for further seagoing adventures. Ironically, it was France, not the United States, that showered him with accolades and awards prior to his death in 1792.

In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt was the driving force behind exhuming Jones’s remains from an obscure graveyard in Paris. As the ship bearing his body entered Chesapeake Bay, seven battleships let loose a 15-gun salute to signal his return to American soil. A hero to Americans and a pirate to the British, Scottish-born Jones had finally come home.

Piercing the Fog of War: Recognizing Change on the Battlefield by Brian Steed, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2009, 306 pp., maps, notes, index, $30.00, hardcover.

Piercing the Fog of War: Recognizing Change on the Battlefield by Brian Steed, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2009, 306 pp., maps, notes, index, $30.00, hardcover.

U.S. Army officer, military historian, and strategist Brian Steed has put together a unique look at battlefields throughout history to help future commanders learn from their predecessors’ mistakes. He scrutinizes seven battles, from the Battle of Cannae in 216 bc to the fighting in Chechnya in 1994-1995.

Steed calls these battles “aberrations,” during which incidents happened that were not expected to occur and transformed the nature of the combat. Such aberrations, Steed notes, will bring defeat to modern commanders unless they recognize them in time. His commonsense advice is to “expect the unexpected and think outside the box.”

It is a well-known axiom in war to know one’s enemy. Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer certainly did not heed this advice at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June 1876. Steed uses this campaign to illustrate his point. Although Custer was a more knowledgeable Indian fighter than the majority of his contemporaries, Steed writes, he was “aberrationally shocked” during the battle and failed to put his experience and training to proper use. The result was a massacre.

Commanders must overcome “arrogant presumptions” when confronting their enemy if they are to achieve victory, Steed writes, warning: “There are more Little Bighorns and more Indian villages, more Crazy Horses and Sitting Bulls waiting to crush some similarly arrogant commander who is unwilling to expand his box because the world fits so well in the box as it is.”

Best Little Stories from the Life and Times of Winston Churchill with his American Mother Jennie by C. Brian Kelly and Ingrid Smyer-Kelly, Cumberland House, Nashville, TN, 2008, 420 pp., notes, index, $16.95, softcover.

Best Little Stories from the Life and Times of Winston Churchill with his American Mother Jennie by C. Brian Kelly and Ingrid Smyer-Kelly, Cumberland House, Nashville, TN, 2008, 420 pp., notes, index, $16.95, softcover.

When Great Britain was in the first throes of World War II, she stood alone against Nazi tyranny. From out of political hibernation came one man that would inspire the island nation to overcome its fear and fight Adolf Hitler’s juggernaut aimed at conquering all of Europe. That man was Winston Spencer Churchill.

In his new book, noted popular historian C. Brian Kelly has gathered a collection of short stories that illustrate Churchill’s childhood, wartime experiences in the Sudan, the Boer War, World War I, and his rise in politics that culminated in his being named prime minister in 1940 and leading the island nation during its darkest hours.

As a sidebar, Kelly’s wife Ingrid has written a chapter in the book entitled “His American Mother Jennie.” In it, she traces Churchill’s mother’s privileged upbringing in New York, her eventual marriage to the abusive Lord Randolph Churchill, and her problematical relationship with her family prior to her death in 1921.

Each vignette clearly demonstrates one aspect of the multidimensional Churchill. Often outspoken and prone to meddling, he nonetheless overcame his depression, which he referred to as his “black dog,” to lead England to victory. Each anecdote leads into the next, and Kelly does a masterful job of linking all of them together so that readers can obtain a better understanding of Churchill’s complex personality. As with all his Best Little Stories series, Kelly has produced a winner with his newest book.

The Man Who Would Not Die: The Remarkable Story of “Lucky” Herschel McKee by Stephen Olvey, Quayside Publishing, Minneapolis, MN, 2008, 272 pp., notes, index, photos, $37.95, hardcover.

The Man Who Would Not Die: The Remarkable Story of “Lucky” Herschel McKee by Stephen Olvey, Quayside Publishing, Minneapolis, MN, 2008, 272 pp., notes, index, photos, $37.95, hardcover.

Here is the account of one incredible man who defied death on numerous occasions. Herschel McKee, given the sobriquet of “Lucky,” left home to fight in World War I. The daredevil teenager enlisted in the French Foreign Legion and soon found himself as a machine gunner on the Western Front.

Mesmerized by flying, McKee found his way into the Lafayette Flying Corps, a polyglot force composed of other Americans, Russians, and Frenchmen. He became an ace at 19 years of age after downing a dozen enemy aircraft. He was shot down in February 1918, but survived the incident to return home at the end of the conflict.

Between the two world wars, McKee’s life reads like an adventure book. In 1919, while he was serving as the riding mechanic for noted driver Andre Boillot, the two crashed their automobile into the wall at the Indianapolis 500 Speedway. Remarkably, both men escaped injury. McKee went on to jump through fiery hoops while riding a motorcycle at circus sideshows. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, he performed death-defying feats for audiences. When the United States entered World War II, McKee achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Army Air Corps and flew on the bombing run over the Ploesti oilfields in Rumania.

McKee was quite the lady’s man as well. When the daredevil pilot and car racer died in 1964 at the age of 67, five women appeared at his funeral, each claiming to have been married to him at some point in his life—a remarkable life, indeed.

The Mexican Wars for Independence by Timothy J. Henderson, Hill and Wang, New York, 2009, 280 pp., illustrations, index, notes, $27.50, hardcover.

The Mexican Wars for Independence by Timothy J. Henderson, Hill and Wang, New York, 2009, 280 pp., illustrations, index, notes, $27.50, hardcover.

Author Timothy J. Henderson has added another book to his growing list on Mexican history. This edition deals with the various wars for independence that were fought between 1810 and 1824. The rebellion began in September 1810 and was led by Mexican-born Spaniards, Mestizos (individuals of European and American Indian background) and Amerindians who desired to be free of Spanish colonialism.

The fighting was soon transformed into a guerrilla conflict after the untimely death of Father Miguel Hidalgo. After years of bloody battles and executions of rebel leaders, Spain finally granted Mexico its independence in 1836.

However, as Henderson explains, there seemed to be no unifying factor among those who desired freedom from Spain. Revenge, cultural integrity, and other personal reasons nearly destroyed the movement. In the end, however, despite the schism that developed between the various indigenous peoples and other ethnic cultures, the Mexican revolution succeeded against all odds.

Jack Hinson’s One-Man War: A Civil War Sniper by Tom C. McKenney, Pelican Publishing, Gretna, LA, 2009, 400 pp., illustrations, maps, index, notes, $25.95, hardcover.

Jack Hinson’s One-Man War: A Civil War Sniper by Tom C. McKenney, Pelican Publishing, Gretna, LA, 2009, 400 pp., illustrations, maps, index, notes, $25.95, hardcover.

When the Civil War erupted, Jack Hinson wanted no part of it. A reserved man, he opted to remain neutral and befriend officers and soldiers on both sides. Hinson was content to run his farm and manage his personal affairs while the savage combat took place around him.

Hinson’s tranquility would be dashed, however, when the conflict finally came to his peaceful valley, Two Rivers, on the Kentucky-Tennessee border. When bushwhackers started ambushing Union patrols and supply lines, they were ordered executed on the spot. Sadly, Hinson’s two sons were mistakenly identified as guerrillas and hanged. Later, their decapitated heads were affixed to gateposts outside Hinson’s home.

Enraged, Hinson sought revenge. Armed with a .50-caliber rifle specially made by a gunsmith, the experienced backwoodsman took to the field with one thought on his mind: an eye for an eye. By war’s end, “Captain Jack” Hinson had killed at least 100 soldiers in his solo war against the Yankees.

Retired Marine Tom McKenney spent 15 years researching the life of Hinson, who was in his late-50s when he ventured out to avenge the murder of his two boys. Despite all attempts to capture him, the one-man army haunted the Federal troops with his deadly long-range accuracy and backwoods skills in hunting and tracking. With Hinson’s death in 1874 from heart failure, McKenney writes, “his weary, one-man war with the Union colossus was finally over.”

Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy by John R. Hale, Viking, New York, 2009, 432 pp., notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy by John R. Hale, Viking, New York, 2009, 432 pp., notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The Athenian Navy was one of the most powerful in the ancient world. The symbol of this mighty armada was the trireme, an agile, speedy vessel equipped with three sets of oars on either side of the boat. This mighty ship would play a pivotal role in the history of Athens.

It was Themistocles, a prominent politician and Athenian general, who first advocated constructing a navy. A hero at the Battle of Marathon, Themistocles finally convinced his fellow countrymen to build a fleet of 200 triremes for their defense and for trade. For the next 158 years, Athens’ nautical empire included more than 200 islands, stretching from the southern Aegean all the way to the Black Sea.

The author, an accomplished archaeologist, asserts that the creation of this formidable navy was also the birth of democracy in Athens. With their vast fleet of triremes, Athenians ventured into the world seeking trade with other nations that eventually transformed the city into the richest seaport during that period. Athenian sailors also brought the idea of a democratic society to neighboring countries, an idea that would take hold and eventually change world history.

Aces High: The Heroic Saga of the Two To-Scoring American Aces of World War II by Bill Yenne, Berkley Caliber, New York, 2009, 349 pp., index, photos, $25.95, hardcover.

Aces High: The Heroic Saga of the Two To-Scoring American Aces of World War II by Bill Yenne, Berkley Caliber, New York, 2009, 349 pp., index, photos, $25.95, hardcover.

Although Richard Bong and Thomas McGuire both came from diverse backgrounds, their outstanding flying abilities and extraordinary bravery put them both on the path of greatness and immortality. Each would receive the Medal of Honor, and they would become the two highest aerial aces in World War II.

Bong, a reserved farm boy from Wisconsin, and McGuire, a smart-aleck city dweller from New Jersey, were enthralled with airplanes at an early age. Both joined the U.S. Army Air Corps and graduated as aviation cadets prior to America entering the war. They would be assigned to P-38 Lightning squadrons in the Pacific Theater, flying out of New Guinea and the Philippines.

Bong would record 40 kills to his credit, and no less than General Douglas MacArthur—himself a Medal of Honor recipient—would personally present the award to Bong. McGuire, unfortunately, did not live to receive his. While on combat patrol over the Philippines in January 1945, the New Jersey native’s aircraft crashed after his engine stalled. At the time of his death, McGuire was just two kills behind Bong. McGuire AFB, in New Jersey, is named in his honor.

Bong met a similar fate in peacetime. While serving as a test pilot at Lockheed’s Burbank, California, site in August 1945, Bong’s P-80 suddenly crashed, killing him instantly. Although there was an intense rivalry between the two pilots during the war, the author feels that those emotions would have been forgotten if both had survived the conflict and met years later. “That’s the mark of true heroes,” Yenne writes.

Faces of the Confederacy: An Album of Southern Soldiers and Their Stories by Ronald S. Codington, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2008, 288 pp., index, notes, photos, $29.95, hardcover.

Faces of the Confederacy: An Album of Southern Soldiers and Their Stories by Ronald S. Codington, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2008, 288 pp., index, notes, photos, $29.95, hardcover.

With the firing on Fort Sumter in 1861, the United States was split in two and war was became a reality. Thousands of men, both northern and southern, rushed to enlist and don the uniforms of their respective armies. With the ongoing advances in photography, soldiers rushed to a studio to have their photographs taken for posterity. These pictures, usually 4 inches by 2.5 inches, were referred to as cartes de visite. Such notables as Generals George B. McClellan and Robert E. Lee posed for the camera, as well as mere privates. Countless cartes de visite survived but, unfortunately, a large number of the individuals cannot be indentified.

Coddington has compiled more than 70 such photographs of identifiable soldiers from various Confederate units and has written a short biography of each. They served in every conflict, both large and small, on land and sea, both cavalry and infantry and even in guerrilla outfits. Their stories are truly noteworthy.

One Confederate officer, James Porter Parker, was George Armstrong Custer’s roommate and close confidant at West Point. The Kentucky native resigned his commission and fought for the South as an artillery officer. Captured at the Battle of Port Hudson, Parker was a prisoner of war for two years before being freed in 1865. The ex-POW migrated west and eventually became a surveyor. He died in 1918, more than 40 years after his friend’s notoriety was cut short at the Little Bighorn in 1876.

Faces of the Confederacy offers the reader an intimate look into the lives of the men who fought, died, or survived America’s bloodiest conflict. Their faces and stances depicted in their photographs demonstrate their determination and fierce loyalty to their cause, a cause that would ultimately devastate their homeland and take years to rebuild.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments