By Glenn Barnett

The little-remembered Battle of Buna was unique among American offensives in the Pacific. It was the only battle that was not preceded by naval gunfire or supported by naval guns of any kind. It was the only battle that did not begin with an amphibious landing. It was the only battle in which the Americans attacked from inland while the Japanese defended the beaches.

Other than Guadalcanal, Buna was the only battle in which air superiority had not been established first. It was the only battle in which an ally (Australia) contributed equally or more so in men, material, and logistics––and took more casualties than the Americans. This is how it happened.

On May 6, 1942, American and Philippine forces on Corregidor surrendered to the Japanese. Even as they did, the next Japanese offensive was already in progress. Steaming south from the island fortress of Truk, a powerful Japanese task force threaded its way through the Solomon Islands and into the Coral Sea. Their destination was the Australian outpost of Port Moresby on the southern coast of Papua New Guinea. The Japanese already controlled two thirds of the vast island and the landings at Port Moresby would consolidate their position and enable them to threaten Australia with invasion.

For five months since the “dastardly attack” on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese had engaged in dozens of amphibious landings throughout the southwest Pacific. Although they had occasionally faced stiff opposition, they had never been beaten. They had every confidence in a new victory.

The Americans had other ideas. The Japanese naval code had been compromised. Admiral Chester Nimitz knew all about the latest movements of the Imperial Navy. He ordered his own task force to the Coral Sea to stop them. The epic battle fought there just one and two days after the surrender of Corregidor (May 7 and 8) turned back the Japanese invasion force. Australia was temporarily safe.

The next month, the Japanese launched a new offensive aimed at Midway Island with disastrous results. Most historians cite the Battle of Midway as the turning point in the Pacific War, but no one told the Japanese. They were still on the offensive.

On July 21, 2,000 Japanese troops were landed on the northeast shores of New Guinea at a mission station and coconut plantation at Buna and nearby Gona. Only a handful of Australian militia were in the vicinity and they beat a hasty retreat inland. A priest and some nuns at the mission station were executed.

The Japanese plan was to march overland across the Owen-Stanley Mountain Range and take Port Moresby from the inland side. They would continue to land troops at Buna to support the offensive. The Japanese expedition was under the command of Lt. Gen. Tomitaro Horii. Horii was a graduate of the Imperial Japanese military academy and had spent several years fighting in China, as had most of his men, who respected him greatly.

The 1,068 men of the 39th Battalion of the Australian militia were all that stood between the Japanese and Port Moresby. They were thrown into battle piecemeal and suffered from lack of supplies, sickness, and high casualties. Sometimes as few as 80 men opposed hundreds of the enemy. They fought a stubborn rearguard action across the tortured foot path called the Kokoda Track, but every time they made a stand, the Japanese outflanked them and forced them back.

Kokoda was hell for both sides. The winding red clay path with hairpin turns snaked its way up and down steep, jagged cliffs through passes as high as 6,000 feet, where cold mists and daily rain penetrated summer clothing. The trail then made rapid descents punctuated by fierce, rain-swollen rivers that cut through the jagged rocks and tangled growth to fall into small valleys where hot, humid jungle and impenetrable swamps plagued both sides with malnutrition and disease.

By mid-August, the 21st and 16th Australian Brigades arrived at Port Moresby to reinforce the disintegrating militia battalion. The 21st was part of the Australian 7th Division, while the 16th was attached to the 6th Division. They had spent the last year fighting the Afrika Korps in Libya. Even after the United States entered the war, Winston Churchill was reluctant to let them go and it would be August 1942 before they were back in Australia to defend their homeland.

In a state of national emergency, the Australians commandeered every commercial and private aircraft in the country to move the men to New Guinea. But even with these hastily sent reinforcements the Aussies were still being pushed back along the Kokoda Track.

Meanwhile, on August 25-26, the Japanese landed 1,200 troops accompanied by light tanks on the eastern tip of New Guinea at Milne Bay. Their air reconnaissance had revealed that the Australians and Americans were building an air base there––a situation that was intolerable to them. Their reconnaissance did not reveal what kind of reception they would receive.

The landing at Milne Bay was opposed by nearly 9,000 Australian and American troops who had been secretly moved there by General Douglas MacArthur. The combined strength of the Allies threw the Japanese back into the sea by September 7, 1942. It was the first time in the war that a Japanese amphibious landing had failed.

While the fighting raged on New Guinea, a new development gave the Japanese reason to pause. The 1st Division of the U.S. Marine Corps landed on nearby Guadalcanal. The Imperial high command immediately recognized the threat. While the Japanese Army was fighting on New Guinea, the Imperial Navy would be tasked with retaking Guadalcanal.

Ironically, it was the same for the Americans. New Guinea was an Army show, while Guadalcanal was the responsibility of the U.S. Navy. Both the Japanese and the Americans now experienced desperate, intraservice rivalry for the scarce resources available.

With the Japanese defeat at Milne Bay, General Horii’s position was vulnerable. The Australians were digging in on Imita Ridge within sight of Port Moresby and the sea. Now they outnumbered the Japanese. Their positions were bombed daily but Allied air power, too, was on the attack, targeting any movement of Japanese supplies they could find. Supply porters brought from their native New Britain deserted into the jungle. Still, General Horii was determined to break through.

The Japanese high command came to the conclusion that they did not have enough resources to contest both the Australians in New Guinea and the Americans on Guadalcanal, so a division of reinforcements meant for New Guinea was diverted to Guadalcanal. Naval ships and aircraft were also diverted. Although they would try to support both battles, Guadalcanal was to have priority.

General Horii received new orders. He was to retreat back up the Kokoda Track to Buna. He and his command were heartbroken. They had come so far and were so close to victory. But orders were orders.

Although no one noticed it at the time, the Japanese position opposite Imita Ridge was the high water mark of the Japanese Empire. On the night of September 20, General Horii began the long retreat that would eventually lead to surrender in Tokyo Bay. Perhaps this, not Midway, was the real turning point in the war.

At first, the Australians thought that the absence of the enemy in front of them was a trick. When they figured out that Horii had retreated, they advanced rapidly.

While the Japanese were experts at advancing, they were not very good at retreating. General Horii failed to support his rear guard, which was chewed up by the advancing Australians. By November 8, the disheartened and exhausted Japanese were back in Buna just in time to face the full brunt of the Allied assault.

So far, the United States’ involvement in New Guinea was sparse. Only 1,300 American airfield-building engineers and artillerymen had seen action at Milne Bay in an otherwise all-Australian show. That soon changed.

The 32nd “Red Arrow” Infantry Division, made up of Wisconsin and Michigan National Guardsmen, along with the 41st Infantry Division of the Oregon and Pacific Northwest National Guard, were diverted from action in the looming North Africa campaign and rerouted to New Guinea; the 32nd reached Australia in May.

Upon arrival, they still wore the flat, World War I-style helmet and were armed with World War I-era Springfield ’03 bolt-action rifles. Some of their field rations dated back to 1918 and were inedible. They were soon issued the Australian equivalent “bully beef” or canned corn beef, which few could stomach.

It took time to re-equip, reorganize, and move to training bases and then abruptly move to new forward bases. The 32nd’s commander, Maj. Gen. E.F. Harding, would gripe, “We were always getting ready to move, on the move, or getting settled after a move.”

The 32nd had seen frontline service in France during World War I and its antecedents stretched back to the Civil War. They and the Australian 7th would carry the heavy end of the battle at Buna. While the 7th had a wealth of experience with desert warfare, it did not, nor did the 32nd, have time to receive any jungle warfare training.

In September 1942, two regiments of the 32nd Division (the 126th and 128th Infantry) were airlifted to New Guinea to support the defense of Port Moresby. For many of the men, it was their very first airplane ride. They arrived without their artillery and most of their equipment; the artillery would not catch up with them until the battle was over.

As it turned out, the 32nd was not needed right away. By the time they arrived at Port Moresby, General Horii had begun his retreat. The Allied command decided that the Americans would support the Australian right flank by making a march of their own over the almost nonexistent Kapa-Kapa Track to the east of Kokoda.

No matter how bad Kokoda was, Kapa-Kapa was worse. The 2nd Battalion of the 126th Infantry would make the miserable trek through the unmapped and unforgiving jungle, over the eerily named Ghost Mountain. Malaria, dengue fever, dysentery, jungle ulcers, ringworm, and athletes’ foot would plague the marchers. Diarrhea was so prevalent that in frustration some men tore the seat out of their pants.

On their perilous 130-mile march, they would be resupplied with air drops along the way. The “Ghost Mountain Boys” would arrive at Buna after an arduous, 40-day slog—exhausted, sick, and unfit for duty. (Their heroic story is told in the book The Ghost Mountain Boys by James Campbell).

In the meantime, an airfield was opened at Dobodura, north of the Owen-Stanley Mountains––some 10 miles from Buna. The rest of the division (including the author’s father) would fly to Buna in 40 minutes.

As the Japanese had retreated back to the coastal towns of Buna and Gona, they lost much of their own equipment in the confusion and unrelenting pressure from the Australians hounding their every step.

During the long fighting retreat, General Horii drowned while attempting to cross a swollen and turbulent river. When the Japanese straggled into the twin coastal outposts, they found that their engineers had fortified a front 10 miles long and two or three miles deep. The challenge had been daunting. The engineers couldn’t dig in very much because the coastal water table was too high, so they built artfully camouflaged bunkers of coconut logs, oil drums, and sandbags at ground level. The fast-growing jungle soon hid these positions.

Inland from the two coastal outposts was an almost impenetrable jungle and mosquito-infested, chest-deep swamplands of impenetrable and foul-smelling ooze. The area was also populated by crocodiles and poisonous snakes. It was here that the Japanese fortified against attack.

In his book, Touched with Fire, author Eric Bergerud noted one of the Japanese advantages: They were armed with the Arisaka Model 38 rifle. (The number was in honor of the 38th year of the Meiji era.) Although long, awkward, and heavy, it was an excellent jungle weapon because its long barrel and small, .25-caliber bullet displayed very little, if any, flash; Japanese smokeless powder was excellent. The combination of no flash, no smoke, and reverberation under a jungle canopy made it almost impossible to tell where a shot had come from. The .25-caliber round was also the same as that used in Japanese machine guns, which eased supply problems.

In November, as the Japanese prepared to defend the coast and the Americans and Australians moved up to attack them, events on the other side of the world shoved the Battle of Buna off the front page. On November 8, British and American armies invaded North Africa.

Suddenly there were three Allied offensives in progress at the same time. In North Africa, more than 65,000 Allied troops were carried by 400 ships, with the support of 300 naval vessels of the combined Royal Navy and U.S. Atlantic Fleet. In all, more than 100,000 men were involved.

On Guadalcanal, only the 1st Marine Division was active in the beginning (Army troops came later), but they were supported by the bulk of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. At Buna, only one American division, the 32nd, and one Australian division, the 7th, were involved (the 41st Division was still arriving in Australia. They would be brought up in the final days of the campaign). However, during the entire campaign, there was no naval support at Buna from any vessel larger than a PT boat. Sea transport of supplies was managed entirely by the small boats pressed into service by the Australians.

Part of the reason for this lack of support had to do with the uncharted waters off the coast of New Guinea between Milne Bay and Buna. Ship captains were not about to risk having their bottoms torn out by unseen coral. Then, too, the Navy had its hands full fending off determined Japanese attacks against Guadalcanal. They did not have ships to spare for New Guinea which was, after all, the Army’s responsibility.

The American public had been riveted by the bloody fighting on Guadalcanal since the Marines landed in August. Now North Africa was getting the attention of the press and capturing the imagination of the people at home. Buna was decidedly on the back burner. Part of the problem was with the commanding general, Douglas MacArthur.

MacArthur had cultivated a mystique back home. From December 1941 until the landings at Guadalcanal in August 1942, MacArthur was the personification of the American fighting spirit. Life magazine had called him “America’s first soldier.”

But the general tightly controlled the news coming out of New Guinea. All press releases were issued from his headquarters in Brisbane, Australia, a thousand miles south of Buna. Unless he gave his approval, there was no news from New Guinea. By contrast, imbedded reporters released much more information to the press and public about Guadalcanal and North Africa.

To make matters worse for the general, the North African landings were led by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had been MacArthur’s aide from 1933 to 1939. MacArthur was no longer America’s only hero. To stay relevant, he had to act fast. He ordered the 7th and the 32nd into action at Buna immediately. The attack would begin on November 19, but it would prove to be a costly mistake. The troops weren’t ready yet.

Worse, Allied intelligence had failed to notice that the Japanese had shipped in reinforcements to Buna by night. So rather than facing an exhausted enemy decimated with casualties and disease, the Allies were up against a fresh and determined enemy force of about 6,500 men.

With no U.S. naval transport ships available to bring men and material to the front, the Allies scrounged to find shallow-draft vessels like fishing trawlers, yachts, and even a captured Japanese landing craft to ferry supplies and troops through the uncharted waters from Milne Bay to the front. The Japanese had air superiority over the battlefield.

At 7:00 pm on November 16, the little flotilla of four boats packed with troops and supplies, which was led by the 80-ton, oil-burning Minnemura under the command of Captain Jack Keegan, were caught a half mile from shore by 17 Japanese fighters. The enemy planes strafed the boats with cannon fire, sinking all of them. Stores of ammunition, food, and medical equipment were lost, along with two 25-pounders, mortars, and machine guns. Thirty-three men were killed and many more were wounded.

Australian journalist Geoffrey Reading was aboard the Minnemura, which grounded on a reef—a sitting duck. He wrote, “Four Zeros selected us as their target and dived over us once with silent guns. They swept overhead like evil birds, went in four different directions, banked steeply, and then they were racing at us, their guns spitting fire and death. The tracer bullets and cannon shells kicked into our side at the water-line, below the wheel-house, and jagged splinters flew in all directions.”

All four ships burned fiercely. The two-masted schooner Alacrity, filled with 30 tons of ammunition, continued to burn and explode for 12 hours. The next day, more boats were sunk or damaged. Only one usable vessel remained afloat, the Kelton, and she could only manage two knots. Until more boats could be assembled, all supplies had to be delivered by air.

That required the support of Lt. Gen. George Kenney. As a trusted member of MacArthur’s staff, he controlled all Allied air assets in Australia and New Guinea, including a pitifully small number of C-47 transport planes. He worked hard to build up the air bases at Dobodura and elsewhere, but Buna was at the end of a very long supply line with too few resources available to move those supplies. Only 60 tons of supplies reached Buna by air in November.

Kenney believed in the extensive use of air power but he had one hide-bound rule. It was his opinion that artillery would not be needed in this fight––his bombers would act as artillery. He had boasted to his superiors, “The artillery in this theater flies.”

Like Herman Göring at Dunkirk, Kenney believed that his Army Air Corps could win the battle. As a result, during the entire Buna campaign, the 32nd Division had but one 105mm howitzer and 200 rounds of ammunition. When those rounds were used up, no more were forthcoming. The gun was parked and forgotten.

The Australians started with no more than eight small guns of various sizes (though more would be barged in later). The biggest was the British-made 25-pounder. They, too, would be short of ammunition.

The most effective Allied artillery was the 81mm mortar. Far more accurate than aerial bombing, Japanese prisoners and captured diaries confirmed that it was the weapon they feared most. At this stage of the war, flamethrowers and bazookas were not available.

The trouble with Kenny’s theory was that the relative positions of the Allies and the camouflaged Japanese positions were hard to locate under the jungle canopy; often American planes would drop their bombs ineffectually in the jungle, in the sea, or on their own men. Frustrated GI’s would start shooting back. The Air Corps was not yet able to provide “pinpoint” bombing.

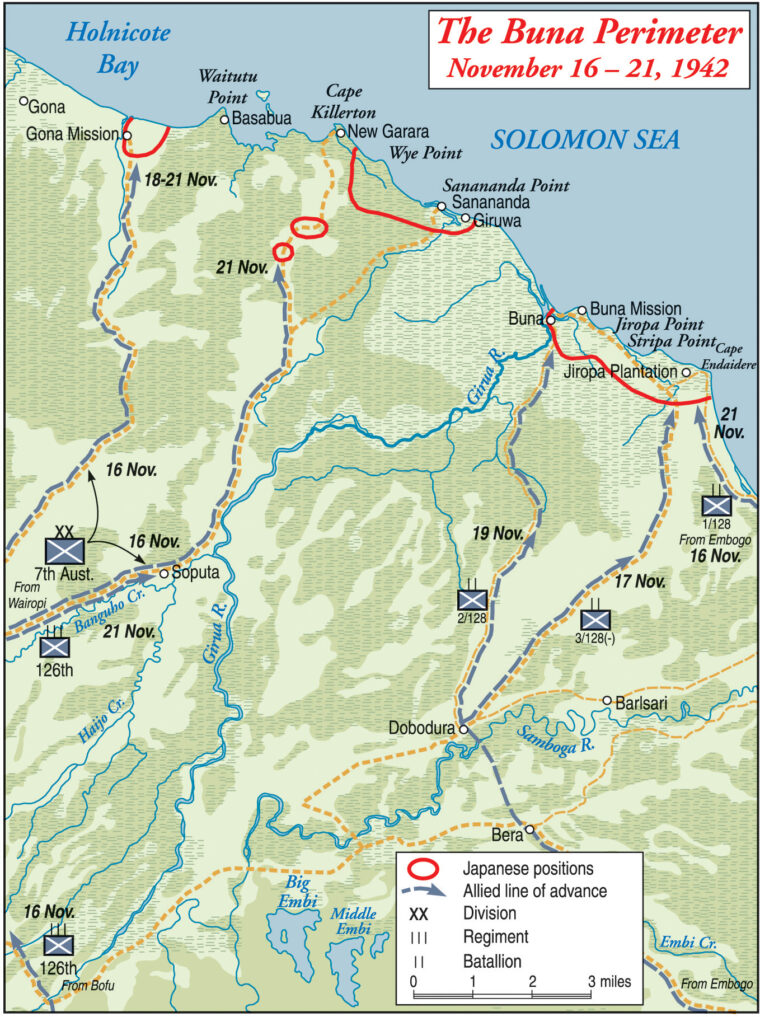

In the approach to the front, the Allies divided up the battlefield between them. On the right flank, the Americans employed three assault groups. The 1st Battalion of the 128th Infantry Regiment attacked up the coast toward the two abandoned airfields. Having lost much of their supplies when the small flotilla of supply boats was sunk by the Japanese, their task was difficult. They would have to attack without all the weapons they needed.

Meanwhile, the 3rd Battalion of the 128th and their support units would attack on another jungle trail to the left of the two airstrips. They would be known as “Warren Force.”

The 126th Infantry Regiment, less the 2nd Battalion which was still slogging away on the Kapa-Kapa Track, moved along a jungle path toward Buna Mission, which was also called “Government Station.” They would be supported by other units and were known collectively as “Urbana Force.”

On the American left, the 1,000 men of the Australian 25th Brigade would assault Gona, 10 miles up the coast from Buna. Although it was not known at the time, Gona was defended by 900 men of a Japanese road-building battalion. All approaches to the coast funneled along narrow dirt paths through malarial swamps, and the Japanese had sited their invisible bunkers and guns in defense of these trails.

On the first day of the attack, it rained all day, grounding support aircraft and making land operations miserable. The Allies advanced along the existing muddy trails which took them directly into the Japanese defense positions. They soon ran into a buzz saw of hidden enemy fire. The jungle canopy muffled the fire, making it impossible to tell where it was coming from. To add to the confusion, the Japanese rotated the position of their machine guns to give the impression that they had far more weapons than they actually did. Not surprisingly, the first Allied assault ended in frustration and a mass of casualties. To add insult to injury, it poured that night.

If anything, the second day of battle was worse. Australian General Thomas Blamey convinced MacArthur that his 25th Brigade was facing more Japanese than the Americans. As a result, the 126th Infantry Regiment was pulled out of the line and placed under Australian command. The 32nd’s General Harding was furious. He had lost half of his command and, to compensate, had to call up his reserves, the 2nd Battalion of the 128th.

On November 20 the assault began anew. Once again it rained and once again the Japanese chewed up the attackers. General Harding begged for the return of the 126th. He was given only one battalion of the 126th––the sick and exhausted Ghost Mountain Boys only just returned from their long ordeal.

All of the movement of men between fronts and piecemeal attacks created confusion in the ranks. Different units lost contact with each other and often with their own buddies in the rain-soaked attacks. Wet, hungry, and dispirited men could not find their units and didn’t care. The rains prevented the airlift of supplies and hindered their movement to the front. Harding’s command was in chaos.

One survivor, Ernest Gerber, described the scene: “Mortars did not fire because they were improperly packed: they were totally saturated with water, and the ammunition was damp. The round would fire, plop out 20 feet in front of the mortar, and that was it…. We had our ammo stored in the old World War I-style wooden boxes … they were falling apart … they were so wet the extractor couldn’t pull the damn things out of a belt. So you couldn’t fire your machine gun. Things like that mount up.”

Air drops were used to try and relieve the supply problem, but there were no proper parachutes available. Planes flew low and slow and crewmen pushed cargo out the back. This resulted in hard impact that would crush and distort bullets out of round so that they would not fit into gun chambers.

Amid the confusion and turmoil, the jungle began to attack both sides. Malaria, dysentery, and other jungle-borne diseases decimated friend and foe alike. When men contracted malaria––and almost all of them did––their temperatures would skyrocket. Incapacitated by fever, chills, and diarrhea, combat effectiveness suffered even further. Without sufficient medication, men with high fevers were laid into streams to cool their bodies. Sometimes they were forgotten.

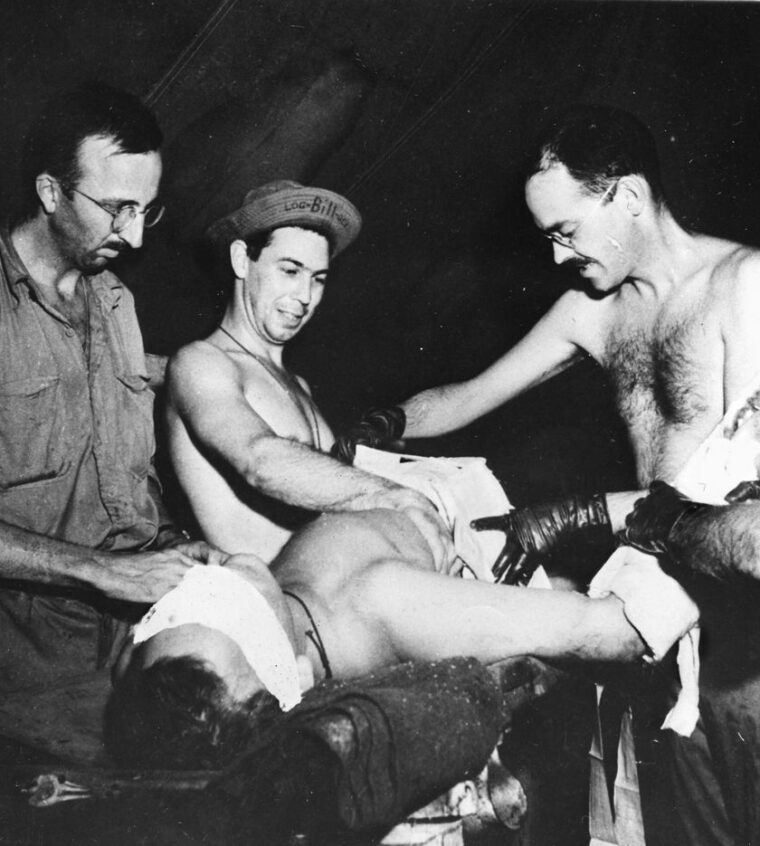

For the 32nd Division, frontline medical attention was provided by Portable Surgical Hospitals (PSH), which operated under a tent and were designed to be easily packed up and moved wherever the fighting was. The forerunner of the M.A.S.H. units in Korea, the PSH was so successful in New Guinea that it was replicated in every theater of the war. But in the early days of the fight for Buna, these small hospitals were plagued by the same supply problems and their personnel subjected to the same sicknesses as everyone else.

In a once-classified report relating the history of the 22nd PSH, this entry was posted on November 17, 1942: “No surgical equipment for major operations has ever been received to date, nor sterilizing equipment, sterile gowns, lap sets, etc. Neither special portable tents nor, in short, any PSH equipment has ever been received to replace what was lost [on the Alacrity].” During the entire battle, the 22nd PSH had to make do without surgical equipment.

As soon as space on cargo planes became available, the wounded were airlifted back to Port Moresby, which itself was mired in confusion. Colonel Wilkinson, the commanding officer of the 171st Station Hospital, remarked, “Four days after we were given this real estate [in Port Moresby], which was covered with high kunai grass, we had 500 patients.”

On November 24, the men of the Urbana Force, working their way up the trail toward Buna, came to a fork in the path where it separated to reach either Buna village or Buna Mission. The area between the diverging trails was heavily fortified by the enemy and became known as “The Triangle.” On that first day of approach, the Japanese lured the Americans out of the fields of tall, razor-sharp kunai grass onto open ground and then opened fire. Forced into the swamps, the GIs lost some of their mortars and light machine guns. After dark, the survivors slipped away to the rear. The Triangle would prove a tough nut to crack.

Two days later, the action shifted to the Warren Force. P-40s and Australian Beaufighters strafed Japanese positions while Douglas A-20 Havocs (or Bostons) dropped their bomb loads for an hour and a half before the infantry kicked off. The bombing and strafing was almost totally ineffectual, and the advancing GIs were immediately stopped cold by well-coordinated Japanese fire. The only result of the advance was casualties.

For the next three days there was a lull in the fighting, allowing time to bring up reinforcements. The Australian 25th had taken some 200 casualties and was pulled out of the line; the 21st Brigade took over on the Gona front. They would suffer 430 casualties over the next five days.

The Japanese, too, tried to reinforce their positions. Four fast destroyers steamed out of Rabaul with 800 troops aboard. Allied air attacks prevented them from disembarking at Gona but eventually 500 soldiers were put ashore some 12 miles up the beach, threatening the Australian left flank.

On November 30, the offensive was resumed on both fronts but only limited, if any, gains were made. Amid the chaos at the front, where the 32nd and 7th were fighting and dying in the stinking, rain-filled swamps with no shelter from sun or rain, rotting clothes and boots, little artillery, no naval support, dubious air support, incurable diseases, and insufficient food and supplies, in the rear they were getting a reputation as cowards.

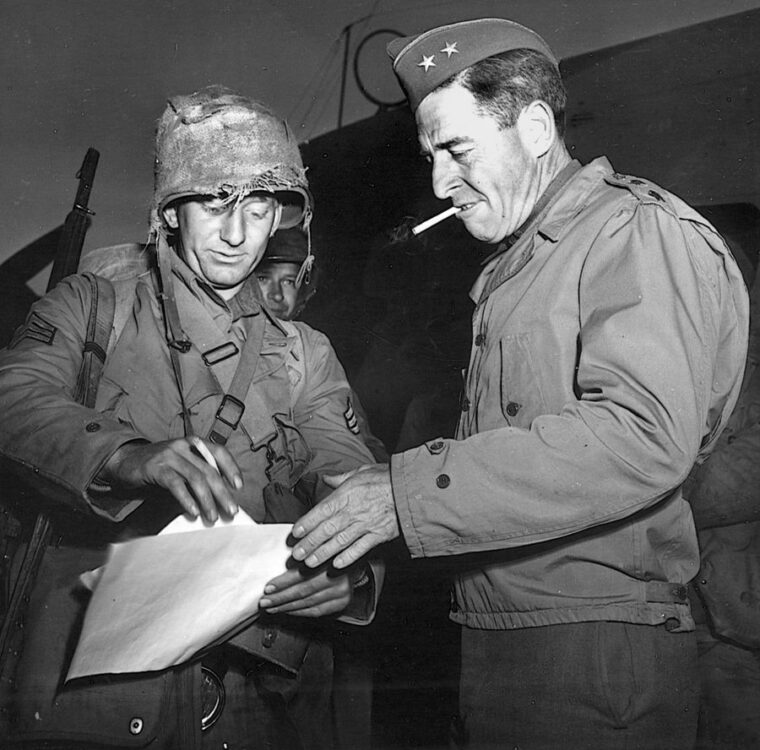

General MacArthur had by now moved his headquarters to Port Moresby. He was frustrated, too. He had received reports of low morale at the front but not the cause of it. He summoned his I Corps commander, Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, and ordered him to replace Harding, adding that if he was successful his name would be released to the press. MacArthur said, “Bob, I’m putting you in command at Buna. Relieve Harding…. I want you to remove all officers who won’t fight. Relieve regimental and battalion commanders; if necessary, put sergeants in charge of battalions and corporals in charge of companies…. Bob, I want you to take Buna, or not come back alive…. And that goes for your chief of staff, too.”

On November 30, Eichelberger had a most uncomfortable meeting with Harding. The two had been classmates at West Point in 1909 (a class that also included George S. Patton, Jacob L. Devers, and William H. Simpson) and had been friends ever since. But orders were orders and Harding was relieved.

The new commander ordered a brief rest for resupply and reorganization. Then he ordered a frontal attack on December 5. On the right, Warren Force was facing two empty airfields and a dense coconut plantation beyond them. They were supported by five Australian Bren-gun carriers that had been secretly barged in at night. Riding on tank tracks, the little “Brens” sported quarter-inch armor and mounted one or two light Bren machine guns that fired a .303 round––the same as used in the Aussies’ Enfield rifle. The Brens were designed for speed, but this advantage was negated in the rugged environment and the need for infantry support.

Moving at walking speed, the Brens initially surprised the Japanese but the adaptable enemy soon recovered. These vehicles were open at the top and snipers hidden atop coconut trees easily picked off the crews. Other Japanese, hidden on the ground, threw hand grenades over the sides. All of the Brens were knocked out in 30 minutes. Under withering fire, the American infantry returned to their original lines. During the night, the Japanese stripped the Brens of their weapons.

On the Gona front, the Australians, attacking from two sides, also failed to break through. But all attempts by the Japanese to reinforce Gona had failed and their strength was significantly reduced from casualties and disease. Most of the Allied attacks that day were met with the same bloody repulse. But one platoon of the 126th, led by Staff Sgt. Herman Bottcher, found a way through to the beach between Buna village and Buna Mission, cutting the Japanese position in half.

Bottcher had been born in Germany. A strong antifascist, he left the country when Hitler came to power and settled in the United States. During the Spanish Civil War, he served with the Abraham Lincoln International Brigade against General Francisco Franco. When World War II came to the United States, he volunteered and was assigned to the 32nd Infantry.

Getting behind Japanese lines, Bottcher was able to attack enemy bunkers from the rear with grenades. Digging in at the beach with only 12 men, he held out against Japanese counterattacks until he could be reinforced. He and his men were credited with killing more than 100 Japanese.

The breech in the Japanese defenses was the first breakthrough in the battle. General Eichelberger was so impressed he gave Sergeant Bottcher a field promotion to captain––and the Distinguished Service Cross.

On December 9, 1942, the Australians finally entered Gona. It had been a costly and brutal victory. The surviving Japanese, desperate to escape, swam out to sea. Backlit by phosphorescent surf, they were shot down by the unsympathetic Australians. The beach was littered with rotting and fetid Japanese and Australian bodies; the stench was overpowering. The Japanese did not have the energy, time, or place to bury their dead. The Australians hastily buried 638 Japanese bodies in necessarily shallow graves.

On that same day, elements of the 127th Infantry, the third regiment of the 32nd Division, began arriving by air at Dobodura to reinforce the drive toward Buna.

By this time, General Kenny’s planes were gaining air superiority over the battlefield. Japanese air losses could not be replaced as more emphasis was given to the desperate fight on Guadalcanal––a fact that helped the Allied supply system greatly. A growing number of available C-47s arriving from the States could now safely fly from Port Moresby to Dobodura and other makeshift fields near Buna.

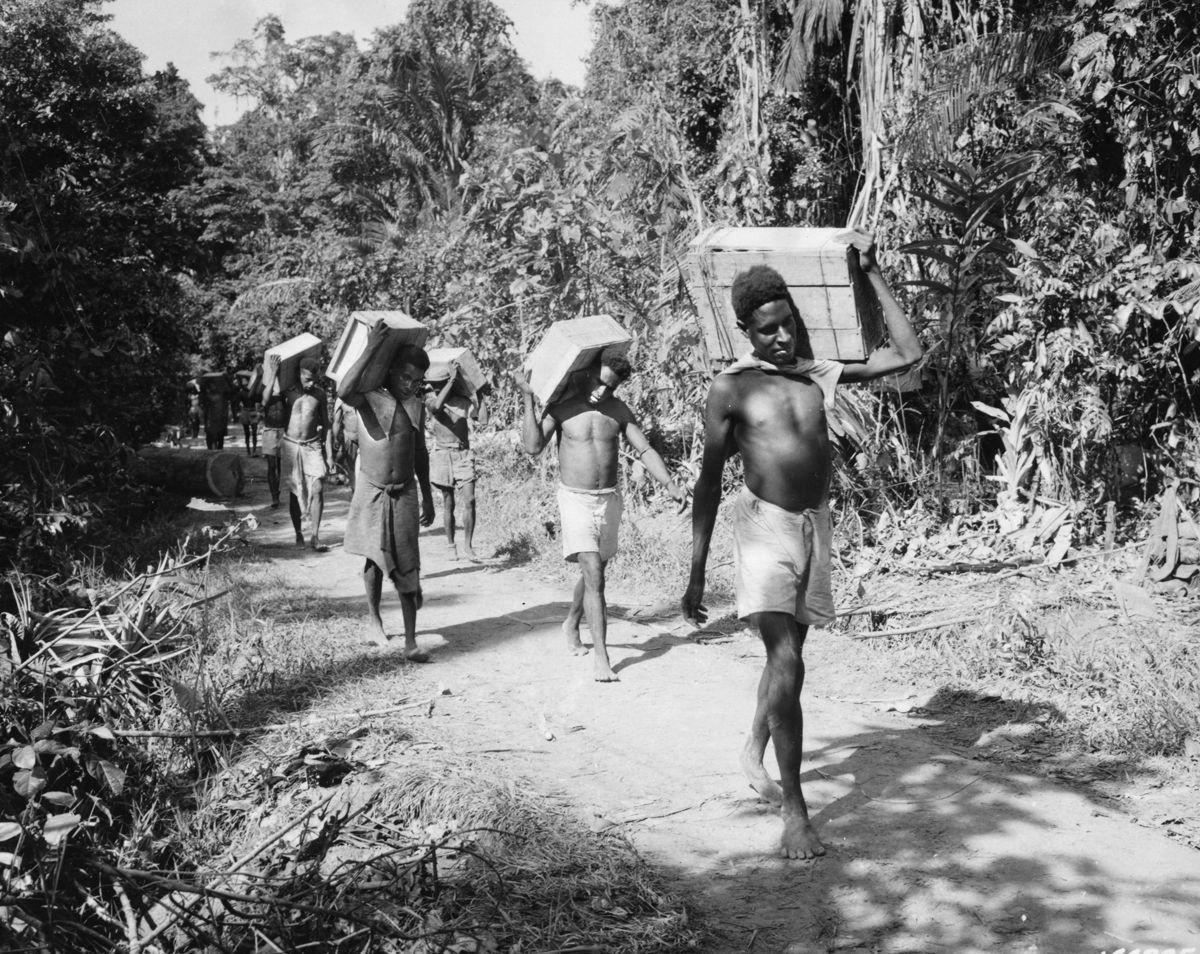

Yet these fields were still some miles from the front. There were no roads and almost no motorized transport. All supplies had to be carried on the backs of men. This could have been a drain on frontline troops to do the carrying but, fortunately, native porters were hired to assume the burden. Called “Fuzzy-Wuzzies” because of their frizzy hair, these local Papuan residents—some displaced from their homes in Buna village—played a major part in winning the battle. They manhandled supplies over alternately muddy and dusty paths to the front and escorted or carried the wounded back out. They would not, however, approach the fighting. They dropped their loads within earshot of the gunfire but would not come closer, so the last mile or two of the supply line was the responsibility of the GIs. Allied engineers were busy building dirt roads to the front, which would make the task of bringing in supplies and taking out wounded much easier.

For the Japanese, resupply was much more difficult. With the allies in control of the air, several enemy destroyers and transports were sunk trying to reach the New Guinea outpost. Limited resupply was made by sporadic air drops. The only Japanese vessels that could make the journey safely were small, fast boats or submarines, and they could only approach during the dark of night. They carried only limited supplies and communications.

The Japanese troops’ stocks of rice grew moldy in the rain and humidity. There was no place for the wounded to be evacuated and few medical supplies for them. The dead piled up and were sometimes used like sandbags to protect Japanese positions. The smell was so foul that living soldiers wore gas masks to endure the stench. The hopelessness that would visit Japanese garrisons later in the war had their origins at Buna.

By the end of December, not even the small boats or submarines could get through as the Americans were able to bring in a few PT boats to conduct nightly patrols to guard against them. The last parachute drop of supplies would be on December 10. The disheartened defenders, inured to hardships that produced victories, could not believe they were being abandoned to defeat.

American casualties were also high. Of the 1,150 Ghost Mountain Boys of the 2nd Battalion who crossed the island on the Kapa-Kapa Track, only 150 were still fit for duty. In many Australian units, too, there were over 50 percent casualties. Both sides suffered greatly in this battle of attrition.

On December 14, elements of the 127th attached to Urbana Force, following a barrage of 400 mortar rounds, broke through to Buna village. It was not defended; the Japanese had deserted their positions and fled along the coast. The event was duly reported to headquarters and a press release went out that Buna had fallen.

The public got the false impression that the battle was over. It was not. Buna village was not the only objective. Buna Mission lay across a small river outlet, still out of reach.

To the east, efforts were still being made to cross the airfields and take the coconut grove. The Bren-gun carriers had disappointed but now the Australians were able to barge in some M-3 Stuart light tanks they had been using in North Africa and knew very well. The American-made tank, named for Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart, mounted a 37mm gun and two .30 caliber machine guns. It weighed in at 14 tons. It was more heavily armored and closed at the top.

Earlier attempts at bringing in tanks had failed when the barges used to carry them sank under their weight. In December, sturdier barges were used to bring up the tanks at night, out of view of marauding Japanese planes. Once on shore, they were moved along the beach at low tide so the rising surf would erase their tracks. Overhead, planes masked the sound of their engines.

On December 18, eight tanks had been secretly moved up to the front lines––lines that had been static for a month. By now, the Americans, growing savvier through painful experience, knew the Japanese positions opposite them pretty well. But infantry alone could not break through. On that day, seven tanks, with one in reserve, supported by Australian and American infantry, moved out against entrenched Japanese positions and advanced northward toward Cape Endaiadere through the coconut grove. At first, they made good progress and several Japanese strongpoints were reduced by tank fire and infantry grenades.

The Japanese, however, recovered and through acts of personal bravery slowed the advance with Molotov cocktails and close-in fighting, which resulted in at least one burned-out tank. Another tank hit a mine and was destroyed. Despite high casualties, a determined final push routed the Japanese. The stalemate was broken. Still, it took six days for the Australians to advance 2,500 yards.

On Christmas Eve, the push was renewed, supported by four tanks. The Japanese had a surprise for them. They had moved a 37mm antiaircraft gun into the path of the approaching Australians and, hidden from view, the Japanese gun opened up on the approaching armor. Within an hour, three of the tanks were hit and put out of action. The attack stalled.

Two more tank attacks would take place in early January of 1943 but they too would fail. Nevertheless, the tanks had broken the stalemate and pushed the Japanese back. Momentum swung to the Allies’ side.

On December 19 and 20, the 127th, having relieved most of the worn-out 126th, made five attacks on the Triangle. All of the attacks failed and created more casualties, causing General Eichelberger to bypass that position all together. To do that, the men had to cross an unfordable stream. Attempts to take a rope across under fire were unsuccessful and, after over two days of trying, Company K of the 127th suffered 54 killed or wounded.

On Christmas Eve, the 127th sidestepped the Triangle and attacked an area known as “Government Gardens.” The misnamed “gardens” was really a stretch of kunai grass that led into a 125-yard-wide swamp followed by a stand of coconut trees that fronted the beach. Nine men made it all the way to the beach but retreated when they were unsupported.

That same day, Warren Force made a big and successful push along the old airstrip. That night, six waves of Japanese bombers dropped more than 100 bombs near the old strip, fraying nerves and keeping everyone awake.

There was no rest on Christmas Day. General Eichelberger wanted the pressure kept on and ordered the attack to be renewed. The Japanese, however, received a Christmas present that night as supplies were successfully offloaded from a submarine. But, by December 27, the Japanese in the Triangle realized that they had been outflanked and quietly abandoned their positions. Japanese planes bombed the coconut grove but were chased away by American fighters.

Focus now turned to the Buna Mission. It was protected by the outlet of Entrance Creek, which crossed behind it before entering the sea; the river would have to be crossed. Again, nothing was easy. A broken footbridge collapsed under the weight of the soldiers and several attacks were repulsed.

By New Year’s Day, Warren Force and Urbana Force linked up and squeezed the Japanese into a smaller perimeter around the Mission, which fell the next day. Several days were still needed to root out the surviving Japanese. Very few prisoners were taken, and these were mostly Chinese and Korean nationals conscripted for manual labor.

The last enemy positions in the area were at Sanananda Point between Gona and Buna, where the Australians were already pressing their attack from the west. Sanananda was perhaps even more heavily fortified than Buna. As many as 5,000 enemy soldiers defended the log-and-sand-filled barrel bunkers and firing pits.

The Australians, augmented with the 1st and 3rd Brigades of the 126th, had made little headway. On January 9, the exhausted 126th was pulled out of the line and replaced by fresh troops. The Australians, too, were reenforced.

With Buna in Allied hands, more troops became available. In addition, the first elements of the U.S. 41st Infantry Division were now arriving and would be thrown into the fight. The 163rd Brigade filled in for Australians who were facing the defenses of the land trail leading to the beach. These men, in turn, were able to support their countrymen in attacks along the beaches.

Torrential rains on January 7 slowed the advance, but on the 12th the Australians pushed off for an assault supported by four tanks. Three of the tanks were quickly put out of action and the attack stalled. On the 14th, an attack by the 163rd up the fortified trail achieved some success, overrunning Japanese strongpoints and killing 100 of the enemy. The next day, more progress was made as the Japanese position along the trail deteriorated.

Meanwhile, elements of the 127th were working their way up the beach on the east side to squeeze the enemy even further. On the night of the 16th, the Japanese had managed to sneak in some barges to take out their wounded. But senior officers, knowing that the end was in sight, had the wounded removed from the craft so that they themselves could be evacuated.

There was yet more hard fighting to do. On January 19, the Australians unleashed a barrage of 250 shells from their 25-pounders and 750 mortar rounds on enemy positions followed by a ground attack. This failed, however, because of a lull between the bombardment and the attack, giving the Japanese time to leave their protective bunkers and reach their firing pits before the attack began.

The following day, coordination of Aussie artillery and infantry was improved. The infantry followed the bombardment closely and caught the defenders before they could leave their bunkers. An important enemy position was overrun and the Japanese death toll reached 525 as a result.

The last enemy resistance ended on January 22. Individual Japanese still had to be hunted down, but General MacArthur won his race with the Marines on Guadalcanal who could not declare victory until February 9, 1943.

The carnage in the Battle of Buna was staggering. The 32nd Division suffered 800 killed, 2,172 wounded, and almost everyone sick from malaria or other disease. It would take nearly a year of recuperation before they were ready to fight again. The Australian casualties were even higher.

As for the Japanese, almost the entire garrison, including the reinforcements who were able to reach them, died. In all, it is estimated that the Japanese lost 8,500 dead. The few wounded and sick evacuated were in such bad condition that they were excused from fighting for the rest of the war.

Future battles would turn in a higher butcher bill, but never again would Americans go into battle so ill prepared.

I wouldn’t say the battle of Buna is “largely unknown.” Perhaps among those who focused on Europe but certainly not anyone with an interest in the Pacific War. The author leaves out something he may not have known, and that is that George Kenney, who had come out of the Air Service but had extensive experience working with ground forces, felt that too much reliance on artillery and air would cause ground troops to lose their will to fight. As for air transport, MacArthur’s strategy, as advocated by Kenney, was to keep hacking airstrips out of the Kunai grass as the Allied troops moved northward toward Buna. One comment – the difference between a Boston and a Havoc was that the former was glass-nosed while the latter had a nose packed with guns. The A-20s used in New Guinea at that time were glass-nosed light bombers that had been converted into powerful gunships as a result of experiments carried out by the legendary Major (at the time) Paul I. “Pappy” Gunn.

Also, in addition to flying ammunition and rations across the Owen Stanley’s, the C-47s and other transports carried wounded back on the return trips, thus beginning an important troop carrier mission. I’m not sure about the author’s claim that airdropping ammunition without parachutes damaged cartridges. As a matter of fact, US quartermasters came up with a method of packing ammunition in ice cream containers with straw and dropping them to Australians on the Kokoda Track several months before Buna. Gravity dropping without parachutes was common not only in the Southwest Pacific but also in Burma. I can see where there might have been problems with artillery shells but not rifle cartridges.

Regardless, the Allied success at Buna was one of the beginnings of the setting of the Rising Sun.

I believe there are a few facts left out.

MacArthur’s race with the Marines on Guadalcanal? One reason the allies were ultimately successful is that the Japanese withdrew large numbers of their troops and sent them to Guadalcanal. Otherwise Buna may have never been taken.

The Australians have never forgiven MacArthur and the US Army for their incompetent leadership that got so many of their countrymen killed. On the other hand, they love the US Marines and Navy. They understand that Sailors and Marines stopped the Japanese southward moves and saved Australia from possible invasion.

There was nothing “pivotal” about Buna. It was a poorly conducted, perhaps unnecessary, bloodbath, while the real work was being done on Guadalcanal.

General Harding, although relieved, kept his stars and was sent to a combatant command in the Panama Canal Zone, thanks to General Marshall. The two men had known each other for many years. In the early 80’s had one of General Eichelberger’s grandsons, a new second lieutenant, as one of my students in a USAF officer technical training course.