By Arnold Blumberg

Imperial Japan’s first hesitant steps toward adoption of armored fighting vehicles occurred in 1925 with the creation of two company-strength tank units. One of these formations was designated experimental and attached to the Chiba Infantry School. At the time, Chiba was the Imperial Army’s center for the development and study of armored warfare doctrine and tactics.

Later that year the government launched the nation’s first domestic program for the design and manufacture of armored vehicles. These activities were overseen by a commission of officers based at the Army’s Osaka Military Arsenal. This body, a section of the Army Technical Headquarters, was made up of young junior officers interested in the design and employment of tanks and their use in combat. Grounded in the tank theories and usage they studied from the experiences of the European powers during World War I, the members of the commission were the prime movers in all future Japanese armored fighting vehicle design and armored combat doctrine and tactics from the mid-1920s to the end of World War II.

Without any previous work in the field of tank design, the Japanese initially looked to Europe for their inspiration. As a result, the first concepts adopted by Japan were multi-turret affairs exemplified by Western patterns such as the French Char 2C, the British Independent, and the German Nbfz, all in vogue in the period 1920 to 1933. The Russian T-35 (produced in 1933) also caught Japanese attention and was copied by them but only in small numbers.

The attraction of these foreign models was based on the Japanese original desire to field “heavy” tanks, each weighing at least 20 tons. The result was the creation of vehicles like the Type 91 (22 tons) and the Type 95 (24 tons). But in 1935 the Japanese came to regret their involvement in the construction of heavy tanks because of the costs in time and scarce materials such as steel that were required to make these weapons. Consequently, Japan turned its focus in a new direction: the design and production of cheap and simple-to-build light and medium machines. The quest to bring into service such a force would govern Japanese tank design and production programs and the tactics these weapons employed through 1945.

The revised thinking by the military regarding tank development had taken root in the late 1920s and early 1930s even while heavy tank production was being pursued. The new direction appeared in the form of the Type 89 medium tank, which first saw production in 1931. Based on a mid-1920s Japanese tank design known as Number 1 Tank, it was built by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. The Type 89 was a 12.7-ton, 18.8-foot-long, 9.17-foot-tall machine covered by a mere 10mm to 17mm of armor plate. Crewed by four men, its main armament consisted of a 57mm cannon and two 6.5mm machine guns, one in the rear of the turret and the other in the left hull front. Powered by a Daimler 105-horsepower, sixcylinder gasoline engine, it had a top speed of 15 miles per hour. The Type 89 was the first domestically produced tank manufactured in quantity. Originally conceived as a light tank of 10 tons, the increased weight caused by its larger symmetrical turret caused the Army to reclassify it as CHI-RO from the Japanese word chugata, meaning medium.

In 1934 the Type 89 was renamed the Type 89-KO, unofficially referred to as Type 89-A. In 1936, this model was replaced for frontline service by the Type 89-OTSU, or Type 89-B, essentially the same machine as the Type 89-KO but with one major difference. The Type 89-B was given a diesel engine, whereas the older Type 89-A used a gasoline engine. They were built primarily by Mitsubishi, in factories established for the construction of the Type 89-B in both the Japanese home islands and Manchuria.

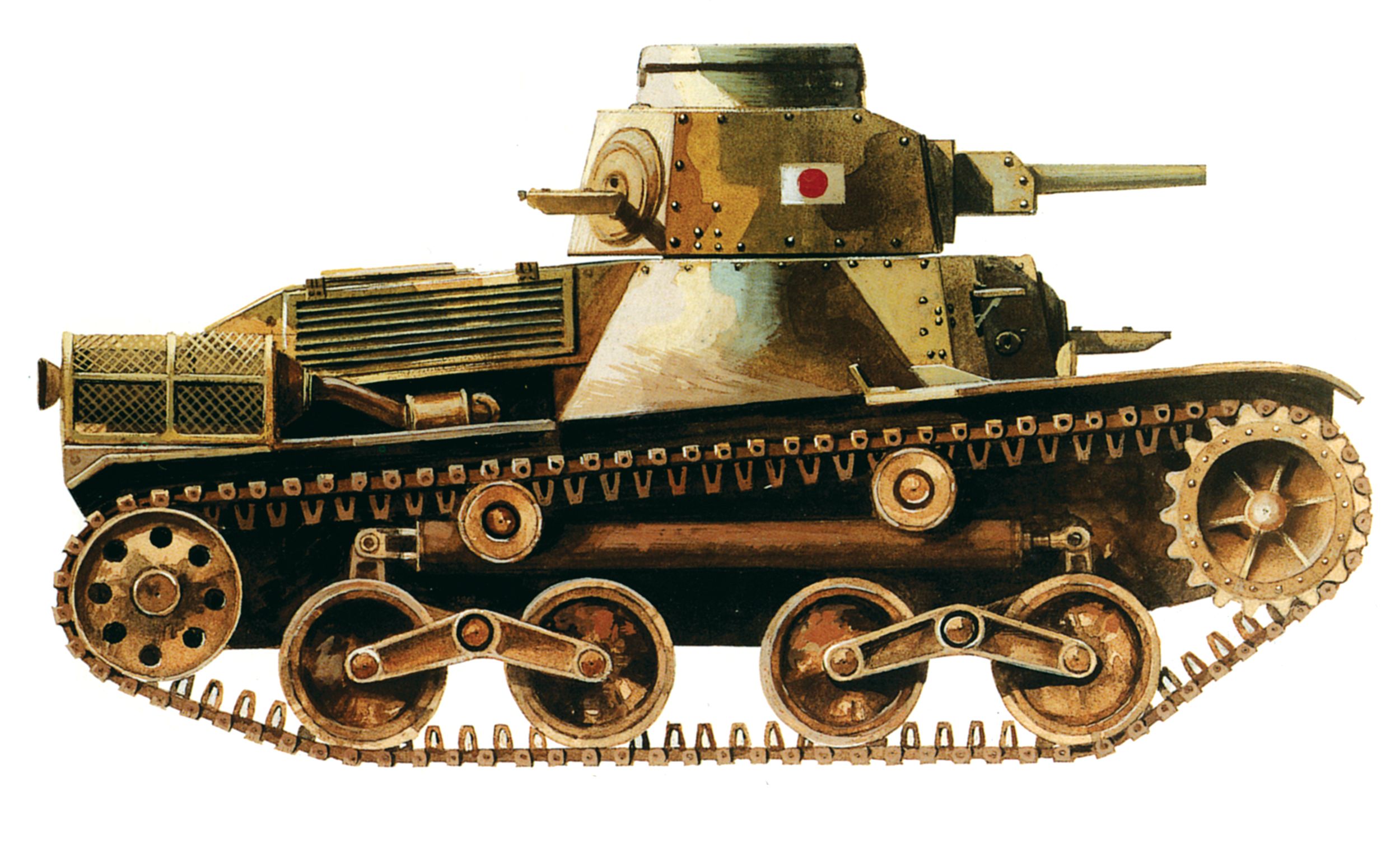

Hand in hand with its interest in tank employment, the country’s War Ministry also toyed with the idea of increased mechanization of the Army on a limited scale. This led to the development in the early 1930s of armored cars that were designated as combat cars or light tanks. The Type 92 Combat Car was the result of this new focus, which was pushed especially hard by the cavalry branch. With a boxed hull contraption that formed a bulge, the Type 92 Combat Car weighed in at 3.5 tons and was operated by a crew of three. It was armed with two 6.5mm machine guns or one 13.2mm cannon mounted in the hull, and another 6.5mm automatic weapon could be placed in the turret. Powered by a six-cylinder, 45-horsepower gasoline engine, this vehicle traveled on three sets of rubber bogie wheels mounted in pairs. Only 6mm of armor protected this alleged armored fighting vehicle.

Another facet of the Army’s tepid adoption of mechanization was the large production, starting in 1934, of a small armored tractor designed to move supplies and keep lines of communication open between the widely scattered Japanese garrisons stationed in Mongolia, Manchuria, and northern China. Designated the Type 94 Tankette, it was a 2.5-ton vehicle that carried a single 6.5mm machine gun in the turret. Later models like the Type 97 TE-KE, first built in 1936, put the diesel engine in the back and replaced the machine gun with a 37mm cannon. This upgraded model weighed 4.5 tons but still was encased in only 12mm of armor plate. Regardless, it proved highly effective against the Chinese, who had few armored vehicles and had to rely mainly on infantry small arms in battle.

Even as the Type 89-B medium tank was being refined after 1936, the Japanese Army realized that the machine was too slow to keep pace in the field with the wheeled transport and newly created mechanized infantry brigades it had formed in 1933 and deployed to Manchuria. The solution to this dilemma was deemed to be the creation of a new lighter and faster tank that would aid the Type 89-B in its role as an armored support tool.

The impetus to enhance the effectiveness of the Type 89-B by teaming it up with another tank model came from the cavalry branch of the Army, which took the opportunity in its quest to replace the Combat Car to push for a updated, speedier armored fighting vehicle. The new tank they got was christened the Type 95 (Kyugo) Light Tank, whose prototype was unveiled in 1934.

The Type 95 was a design of 7.4 tons employing the same six-cylinder, 110-horsepower diesel engine that powered the Type 89-B. Named the HA-GO (for light tank), it required three crew members: a driver, a machine gunner working two 7.7mm automatic weapons in the hull, and a commander-gunner firing the turret-mounted 37mm ordnance piece. Protected by 6mm to 12mm of armor, it could travel at a maximum speed of 25 miles per hour.

By early 1936 the machine was in full production with Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, the main manufacturer. It was not until mid-1942 that other companies were called upon to build the Type 95. By war’s end, 2,400 units had been made. The Type 95 would be replaced after 1943 by a limited number (about 200) of the Type 98KE-NI, or Type 98-A. With a more efficient 37mm main gun and a speed of 31 miles per hour, the Type 98 was marginally better than its predecessor even though it had identical armor protection.

As early as 1936, the members of the Army Technical Headquarters understood that the Type 89-B tank was inferior to its European counterparts in all the major categories. It was underpowered, underprotected, and undergunned. Overriding the Army General Staff’s Operational Section, the Technical Headquarters secured its own proposal for a better medium tank in 1937. This new model was known as the CHI-HA. Construction was by welding and riveting, and the armor was slightly curved. A small two-man turret was mounted to the right of the hull and housed a low-velocity 57mm gun. The three 7.7mm machine guns—one installed in the hull front, one in the rear of the turret, and sometimes one fitted as an antiaircraft weapon—provided reasonable antipersonnel firepower. Armor protection was 25mm steel plate encasing most of the tank’s body. Driven by a strong V-12 air cooled diesel 170-horsepower engine, the CHI-HA had a speed of 24 miles per hour and an average range of 130 miles.

Produced by Mitsubishi, this model saw rapid modification and improvement after the Russo-Japanese conflict in Manchuria in 1939. A new version, the Type 1 CHI-HE with 50mm of armor, was slated to go into full production by the end of 1941. To speed the deployment of this tank and to overcome the technical difficulties that were retarding output of the new machine, former CHI-HA models were fitted with Type 1 CHI-HE turrets. This combination became the Type 97 Shinhoto-Chi-Ha (“new” or “modified” turret) medium tank.

The Type 97, which came into service in 1942, was in most regards close to what the Chi-Ha had been except for a centrally located turret that mounted an improved 47mm cannon. Operated by five men, the Type 97 weighed 16 tons and was 18 feet long; seven feet, eight inches wide, and almost eight feet high. The same powerful Type 100 V-12 diesel engine was used. The Type 97 was the best tank the Japanese had during the war, being comparable to the early German Mark III. It also made up the majority of the Imperial Japanese Army’s armored fighting vehicles from 1942 onward.

A number of very real constraints on Japanese tank design and construction dictated what type of and in what numbers such vehicles could be manufactured during the period between 1930 and 1945. First, size and weight restrictions were significant because of the infrastructure of the county. Prewar Japan lacked the numerous wide roads found in Europe and North America. Consequently, the nation’s railways, with a track gauge of only 3.5 feet, had to carry all the armored traffic. As a result of the rail network’s narrow gauge, tank design could not exceed a width of 8 feet for any vehicle.

Second, Japan’s island geography meant that only through sea transport would its military equipment reach any war zone. This reality meant that in order to ease ship storage and handling, the sizes and weights of armored fighting vehicles would have to be minimized. This translated into the requirement for lighter tanks with thinner armor protection and smaller caliber main armament.

Economic factors also played a key role in Japanese tank construction. Prior to World War II, the government was extremely cost conscious and preferred to build smaller, therefore cheaper, armored fighting vehicles. The cost of manufacturing was dictated by the powerful politically connected private business sector, which not only built the product but put forth designs and specifications as well. There was little governmental control over what the giant manufacturers demanded in cost per unit or in quality control.

Also, the nation’s industrial base was not large enough to carry on large-scale tank production along with other wartime arms manufacturing necessities. Only 12 factories in 1941 had the capacity to produce tanks, and these were situated in Manchuria as well as in the Home Islands, thus making the transfer of raw materials, parts, and labor very time consuming and expensive. By 1944, the number of facilities making tanks had been reduced to just four because of the urgent need to build more ship and plane engines to sustain the war effort. Japan’s capacity to produce steel and iron for armored fighting vehicles had always been scarce and was the prime reason that the creation of those weapons had fallen from manufacturing Priority A in 1941 (the highest production level) to Priority D (the lowest level) by late 1943.

The will to field a strong armored force was also lacking in the ranks of the Army high command, and this explains the tepid support that armor was accorded during the war. The nation’s military leaders felt that the war zones their armed forces would be engaged in—the Pacific islands, Southeast Asia, China, and Manchuria—offered little scope for large-scale armored warfare operations. This was the consensus since the Japanese opponents in those areas possessed little or no tank strength that could interfere with Japan’s intended aggressive moves.

As a result, the Japanese government allowed for the manufacture of a mere 1,024 tanks of all varieties in 1941 and only 1,290 in 1942. And these years proved to be the peak period for Japanese tank production during the entire war! In contrast to the 6,300 tanks the Japanese constructed from the 1930s to the end of the Pacific War, the United States built 4,000 tanks in 1941, then 24,000 the next year.

As the war progressed, Japanese tank organization evolved from regimental Sensha Rentai (regiments first formed in 1938) to group to division level in order to better control multiple regiments. Tank Groups (Senshadan) comprising three regiments were raised in Manchuria between 1938 and 1940, with another regiment, the 2nd, formed in Japan to be used in the Malaya campaign.

A failure as a combined arms team because it did not contain infantry, engineer, or artillery formations, the tank group was supplanted by the division (Sensha Shidan) concept starting in mid-1942, with the creation of four tank divisions by 1944. Each division held two tank brigades (Sensha Ryodan) of two regiments each. It was touted as an all-arms force, and its supporting artillery regiment was towed, not self-propelled, and the ratio of three infantry battalions to four tank battalions was too high. A division’s order of battle called for each tank regiment to have 1,071 men and 78 tanks, an infantry regiment of 3,029 men, as well as artillery, antitank, reconnaissance, engineer, and maintenance units.

In addition to divisions, the Japanese Army had a plethora of independent tank companies (Dokuritsu Sensha Chutai), 12 of which served on Saipan and the Philippines, mostly occupying static defensive positions.

Japanese tank regiments held 750 to 850 officers and men (tank troops were collectively called Senshahei), manning 30 to 50 tanks. A full colonel usually commanded the regiment, while majors and captains ran the companies, and sub-lieutenants officered platoons. Maintenance, supply, and medical units were integral parts of the regiment. Usually three or four tank companies (three medium and one light) made up the unit. Three or four tank platoons of three to five tanks each formed a company.

But tank strength in a regiment was always a problematic issue due to losses from combat and poor maintenance. Also, as the war dragged on, Japanese tank crew shortages grew acute in both numbers and efficiency. Since the Army did not send dismounted tankers back from the front, using them instead as regular infantry, experienced crews rarely got the chance to impart their expertise to replacements in the tank corps.

Japanese tank doctrine as devised in the 1930s stated that the tank’s primary mission was to support friendly infantry. Typically, one tank regiment would be attached to an infantry division, which in turn would attach one tank company (Shidan Sensha Tai) to each infantry regiment. The tank division’s light tank company would be retained for reconnaissance and flank protection tasks. This practice of using tanks in “petty-packet” fashion prevented the best use of the weapon, which required mass and shock action.

At the start of the Pacific War, tanks were treated as mobile guns, firing as they moved to suppress enemy machine-gun and artillery positions in order that the favored arm of decision, the infantry, could capture contested ground. By late 1942, reacting to the successes of the Germans during the first years of the war, the Japanese had revised their tank doctrine and decreed that the tank was now the main strike force and that all other arms were there to support it. This new theory of tank combat was based on the possibility of conflict with the Soviet Union on the vast Asian plains.

A small amount of armor was deployed to the Pacific area. Tanks of the 1st Independent Tank Company, about 12 Type 97 mediums under Captain Yoshito Maeda, were used on Guadalcanal. The protracted battles in New Guinea saw their use but to little effect due to the lack of roads; muddy, mountainous terrain; and thick jungle. A few score were sent to the central Pacific atolls, where it was envisioned that they would charge at the Americans as they landed on the beaches. This hope was soon dispelled by American firepower, and the tanks were relegated to being not more than static firing positions.

Tank units were also sent to the larger, western Pacific islands, but the roadless, hilly, and densely forested terrain reduced mobility. This, combined with piecemeal commitment against superior American Sherman and Stuart tanks— with their thicker armor protection and sporting 75mm and 37mm guns respectively—caused most Japanese commanders to use their vehicles in dug-in positions to avoid the lethal enemy tank fire.

Tactically, Japanese tankers were urged to be aggressive; it was not unusual for tanks to continue an advance even after their accompanying infantry was left behind or had fallen back. If unsupported, tank crews would dismount to clear obstacles themselves and even attack the enemy troops covering them. When attacking, companies would assume the T formation (Choji) with three platoons and the headquarters section deployed in line and a fourth platoon to the right center. When the assault went in, the front units established the firing line while the rear platoon attempted to hit the enemy flank or guarded its own company flank.

When assaulting antitank defenses, the tanks would be formed in attack waves. If the defenses were light, they would be massed forward. Infantry would closely follow the armor and sometimes ride into battle on the machines. Tank training stressed rapid and concentrated fire. Fire tactics included firing on the move, firing as the vehicle moved and stopped and moved again, and firing at the halt. Acknowledging their light armor, Japanese tankers tried to fire from behind terrain or obstacles that would completely hide the tank from enemy view. A favorite tactic of the Japanese was the night attack.

After the Russo-Japanese fighting in 1939, the Japanese improved their antitank tactics. The use of smoke shells allowed the Japanese tanks to maneuver to the flanks and rear of the enemy. Ambush proved effective against roadbound American armor in the Philippines in 1944-1945. When on the defensive, especially on the Pacific islands, tanks were dug in with only the turret exposed to allow all-around fire. Such tank positions were mutually supporting when possible.

Considering all the inherent problems the Japanese armored force had to contend with as the war went on, its shortcomings were not anticipated by senior officers during the first year of the war. This condition was bolstered by the spectacular victories over the Western powers in the Malaya and Philippine campaigns of 1941-1942. Here Japanese armor proved to be an indispensable tool in achieving early conquests.

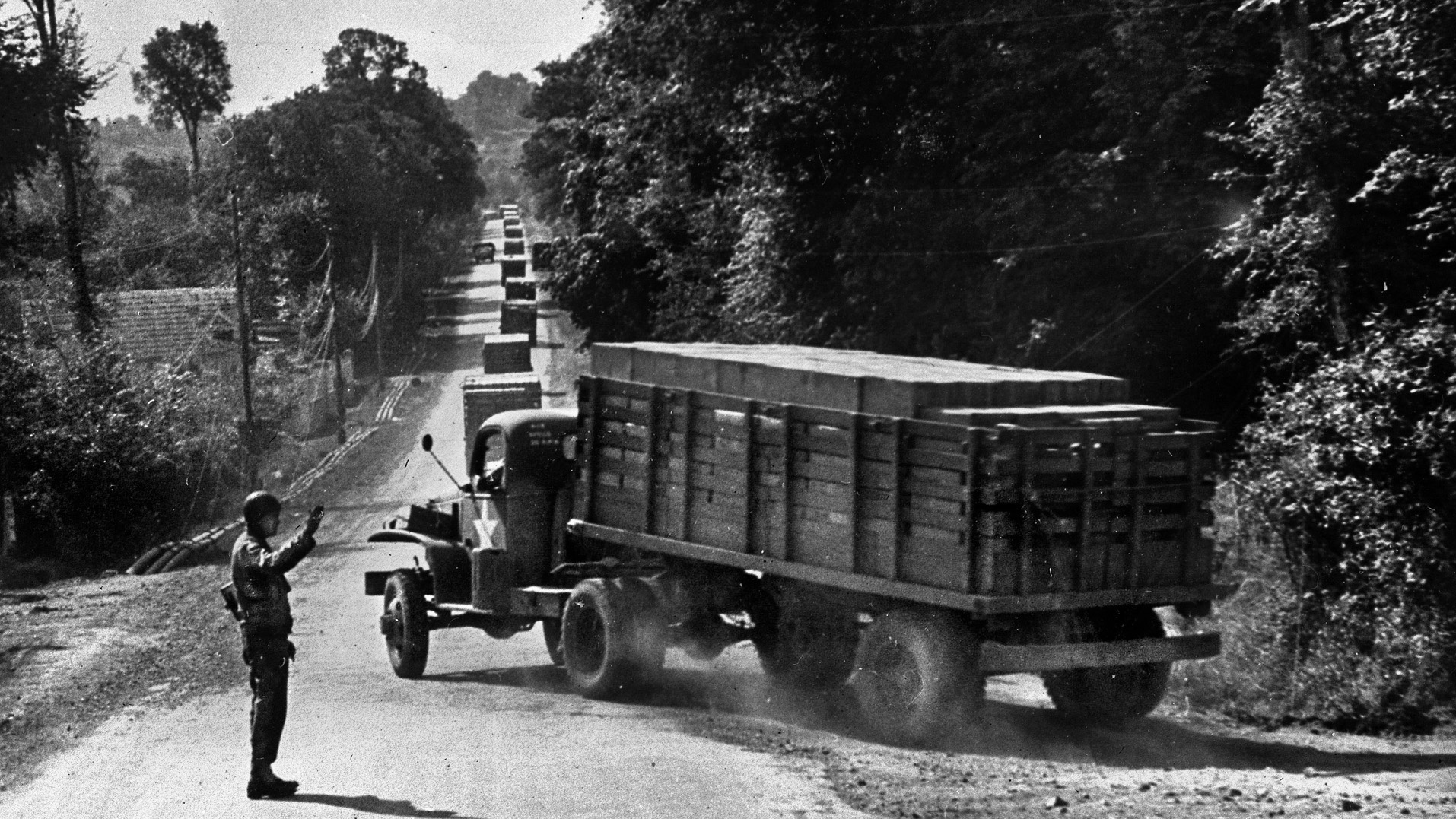

The assault force against Malaya was made up of General Tomoyuki Yamashita’s 25th Army. As part of his host, Yamashita had at his disposal the 3rd Tank Brigade composed of two armored regiments, about 120 operational vehicles. Tanks were used aggressively and uncharacteristically en masse as Lieutenant Colonel Saeki, commander of Tank Detachment Saeki (some 50 Type 94s and Type 97 tankettes), detailed Lieutenant Sigeru Yamane’s 3rd Tank Company (11 Type 97 medium tanks and a few tankettes), 1st Tank Regiment, to race ahead on the road leading from the landing beaches near the border with Thailand through British defensive positions.

The shock of the attack forced the enemy to retreat in panic and threw open the route to the rest of Malaya. Using tanks to continually leverage the British, Australian, and Indian defenders out of positions, the Japanese advanced south. Without tanks of their own or any reliable antitank weapons, the Commonwealth troops were powerless against the rampaging Japanese armor. The 25th Army drove quickly for Singapore, 400 miles to the south, smashing the British river defenses at the Slim River in January 1942 with a night attack by 10 Type 97 medium and five Type 95 light tanks. The landing of armor on the island of Singapore in early February 1942 sealed the fate of the fortress as well as its 70,000-man garrison.

As Japanese troops landed in Malaya and Burma in early December 1941, General Masaharu Homma’s 14th Army invaded the American protectorate of the Philippines. Supported by two armored regiments, the 4th and 7th, the Japanese quickly overran their American and Filipino opposition. Colonel Sonda’s 7th Tank Regiment, fielding 34 Type 89-B medium, 14 Type 95 light, and 2 Type 97 medium tanks, made its presence felt during the campaign and contributed greatly to its success by supporting Japanese infantry attacks.

This operation also witnessed the first employment of the type 97 Shinhoto Chi-Ha in combat. Pushed to the forefront during every advance on Luzon, the Japanese armor conducted numerous running fights with the 100 American M5 Stuart light tanks on the island, losing many machines to the better U.S. armor and antitank guns. But the Japanese tide could not be halted. The March-April 1942 offensive to capture the American-held Bataan Peninsula was successfully headed by 25 tanks of the 7th Regiment against stiff U.S. resistance.

After the stunning triumphs of 1941-1942, the Japanese wave of conquest receded in the face of the inexorable march of the Allies across the Pacific and Southeast Asia. Japan’s armored corps participated in defensive operations, occasionally as a mobile strike force. This was the case on Saipan in June 1944, when a mixture of 37 Type 97 light and Type 97 medium tanks of Colonel Masa Goshima’s 9th Tank Regiment launched a predawn assault on the U.S. 2nd Marine Division and was almost wiped out for its trouble.

In January 1945 on Luzon, the Japanese 2nd Tank Division lost 108 of its 220 machines during a week of combat. More often dug in and acting as armored pillboxes, Japanese tanks and their crews fought to the end against superior American armored fighting vehicles and other firepower brought to bear on them. In these bitter actions, the tankers of the Rising Sun exhibited the same courage and fierce determination to win or die as they showed during their glory days in the first year of the war.

Military historian Arnold Blumberg lives and writes from his home in Baltimore, Maryland.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments