By Steven Weingartner

The outbreak of World War II on September 1, 1939, found the United States in an isolationist mood that precluded, for the time being, any direct involvement in the conflict. It was a good thing—the nation was wholly unprepared to fight a large-scale war. Raw numbers told the story. Germany, for example, invaded Poland with more than 1.5 million men organized into five armies comprising six armored divisions, eight motorized divisions, and 27 infantry divisions. Poland, weak by comparison, fielded 30 infantry divisions, 11 cavalry brigades, and two motorized brigades. In contrast, the United States Army had just under 200,000 men parceled into five under-strength and ill-equipped infantry divisions and one cavalry division. Only four of the divisions were based in the continental United States; the other two were based in the Hawaiian and Philippine islands.

Among the former was the 1st Division. Known as the “Big Red One” because of its distinctive shoulder patch—a red numeral on an olive-drab shield—the division was constituted on May 24, 1917, as the First Expeditionary Division. The first American division sent to France (lead elements arrived at Saint Nazaire on June 26, 1917), the Big Red One also won the initial American victory of the war at the Battle of Cantigny on May 28-31, 1918, and was a key participant in virtually every other American action, notably the Battle of St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne offensive (September-November 1918). Not coincidentally, the Big Red One suffered the most casualties of any American division, with more than 22,000 killed, wounded, or missing by war’s end.

Following the Armistice on November 11, 1918, the division occupied a sector near Coblenz, Germany, until August 1919, when most of the soldiers returned to the United States. For the next 20 years the division was headquartered in Fort Hamilton, New York, with its component units dispersed to various posts on the East Coast. In the autumn of 1939, the Army converted to a “triangular” structure, and the division was reorganized into three infantry regiments (16th, 18th, and 26th), while the 28th Regiment was assigned to the 8th Infantry Division.

With the triangular structure, each regiment numbered 3,300 infantrymen. Regimental combat teams were formed for specific missions by adding quartermaster, medical, ordnance, engineer, reconnaissance, signal, and artillery troops. In addition to organic cannon companies within the infantry regiments, the division had four artillery battalions: the 5th, 7th, 32nd, and 33rd Field Artillery, each with a complement of 520 men. Collectively known as the 1st Division Artillery, these battalions contained several venerable units: Battery D of the 5th (Alexander Hamilton’s Battery) had a history that extended back to 1776 and the Revolutionary War. The 7th was constituted on July 1, 1916, and assigned to the 1st Expeditionary Division on June 8, 1917. The 32nd and 33rd were constituted on July 5, 1918, and assigned to the 1st Division on October 1, 1940. The division also included the 1st Engineer Battalion, formed in 1846. The overall strength of the division was nominally 15,000 men, although this figure varied with circumstances.

In the two years preceding the events of December 7, 1941, Congress, responding to increasingly ominous developments in Europe and Asia, enacted legislation aimed at readying the nation’s military and the nation for possible entry into the war. The institution of the nation’s first peacetime draft in June 1940, along with the passage of generous appropriations bills, provided the Army and Navy with three much-needed commodities: men, money, and matériel. A prime beneficiary of this congressionally mandated largesse, the 1st Division put it to good use in a training regimen that included participation in several large-scale maneuvers. Such training was necessary because of the changing character of the Army. By late 1941, very few 1st Division troops, mostly officers and NCOs, were career soldiers. The rest were essentially civilians in uniform. Some had been drafted into the Army, others had enlisted; in either case, they tended to have no prior military experience.

In May 1940. the division proceeded to Sabine, Louisiana, to participate in maneuvers, where it functioned as a triangular unit for the first time. Division headquarters returned to Fort Hamilton in June, and its component units were sent to Forts Hamilton, Jay, Wadsworth, and Slocum and Plattsburgh Barracks, all in New York. On February 4, 1941, the division moved its headquarters at Fort Hamilton to Fort Devens, Massachusetts, with the rest of the division soon following. The division practiced landings at Buzzard’s Bay, Massachusetts, and underwent additional amphibious training in August with the 1st Marine Division at New River, North Carolina.

In the autumn of 1941, the division was involved in maneuvers in North Carolina. It returned to Fort Devens in the first week of December, shortly before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. More amphibious training at Virginia Beach, Virginia, in January 1942 was followed by infantry training at Camp Blanding in Florida and air-ground tests and demonstrations at Fort Benning, Georgia. Upon the conclusion of the Benning exercises, the division moved to the Indiantown Gap Military Reservation in Pennsylvania on June 21, 1942, to conduct more combat training and to assemble for overseas movement in August.

By then, the Allies in effect were fighting two separate wars: one in Asia and the Pacific, the other in Europe (including the Soviet Union), North Africa, and the Middle East. The Allies’ Europe First policy, formulated by American and British military planners in the opening months of 1941, gave priority to defeating Germany. Not coincidentally, it determined that the 1st Division would direct its efforts at the Nazis.

The first units of the Big Red One to make the Atlantic crossing, an advance headquarters detachment and the 2nd Battalion of the 16th Infantry Regiment, departed by ship from Brooklyn, New York, on July 31. The rest of the 1st Division departed Indiantown Gap on July 30, arriving in New York City on August 1 and boarding HMS Queen Mary for an uneventful transatlantic crossing. After docking at Gourock, Scotland, on August 1, the men boarded trains to Tidworth Barrack, a former cavalry post near Salisbury, Wiltshire, 50 miles southwest of London. The division spent a little over two months at Tidworth, training feverishly for the inevitable day when it would be committed to combat. After completing an amphibious exercise in Scotland on October 18, the division embarked on transport ships in the Firth of Clyde, where the greatest assault fleet ever assembled was staging for Operation Torch—the invasion of North Africa.

Prior to Operation Torch, the war in North Africa was fought primarily in Egypt and northeast Libya, in an area extending west from El Alamein in Egypt across 500 miles to El Agheila on the border of Tripolitania. The arena of combat encompassed the Western Desert and the adjacent coastal strip as well as the fertile region of the Jebel Akhdar (Green Mountains). For more than two years, Axis and British armies had conducted a series of campaigns across the length and breadth of the disputed region, alternately gaining and losing vast expanses of territory without producing decisive results.

By the first week of January 1942, the advantage seemed to lie with the British, who had captured all of Cyrenaica and advanced past Mersa Brega to the outskirts of El Agheila. But on January 21, 1942, an Axis army commanded by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel went on the attack, driving the British Eighth Army out of Mersa Brega and advancing to the Gazala-Bir Hacheim vicinity. There, Rommel’s forces halted and the front remained stable for more than three months while the adversaries recouped their strength for the next round.

On May 26, Rommel resumed the offensive with an assault on the so-called Gazala Line. In the ensuing Battles of the Cauldron and Knightsbridge, Rommel’s forces destroyed the bulk of the British armor and sent the battered Eighth Army reeling back in disarray through Helfaya Pass, just inside the Egyptian border. Rommel’s forces captured Tobruk on June 21, 1942, Mersa Matruh on June 27, and Fuqua on June 28. By the 30th they had driven to the outskirts of El Alamein, where the British were preparing to make a final stand.

El Alamein was a mere 150 miles from Cairo, a comparatively short haul when measured against the distances Rommel had covered in the preceding weeks. It was as close as he would get to that city. Repulsed in the First Battle of El Alamein and the Battle of Alam Halfa, Rommel was decisively beaten when a revitalized British Eighth Army, now commanded by General Bernard L. Montgomery, went on the offensive on the night of October 23-24 to begin the Second Battle of El Alamein. By November 8, when Operation Torch began, Rommel’s forces were retreating west along the Libyan coast.

The Second Battle of El Alamein was raging when the Clyde armada, comprising Torch’s Center and Eastern Naval Task Forces, departed the firth in two convoys on October 22 and 26, bound for Algeria. Passing through the Strait of Gibraltar between November 5 and 6, Center and Eastern Task Forces arrived off Oran and Algiers, respectively, on November 7 and began landing west of Oran at Les Andalouses and east of the city at Arzew. There the enemy was not Germans, but French forces nominally loyal to the collaborationist government in Vichy, France. French resistance ran the gamut from none at all to fierce fighting. The Allies captured Algiers on November 8. Two days later Oran was secured, and in Algiers Admiral François Darlan, high commissioner for the Vichy government, ordered his troops to lay down their arms. The next day the French in Algeria and Morocco signed an armistice with the Allies, ending the opening phase of the North African campaign.

In the final week of November, the 1st Division began to be committed on a unit basis to the Tunisian front. Among the first units to go was the 3rd Battalion, 26th Infantry, which was flown east to Youk les Bains in southern Tunisia and then deployed in outposts guarding the south and east approaches to the Atlas Mountains. On November 23, the 5th Field Artillery Battalion joined the British V Corps and elements of the U.S. 1st Armored Division in northern Tunisia. In early December, the 18th Infantry Regimental Combat Team was also attached to British V Corps. The 18th fought alongside British units (notably the Coldstream Guards) in battles at Longstop Hill and Medjez el Bab during the abortive Allied drive on Tunis in late December.

In early January, the rest of the 26th Infantry Regiment and the 33rd Field Artillery Battalion joined the U.S. II Corps in southern Tunisia. The remainder of the division moved into the area between January 18 and 24, concentrating in the vicinity of Guelma, 60 miles east of Constantine. By January 25, the entire division was in Tunisia. However, due to a series of emergencies confronting Allied forces at this stage of the campaign, division elements were committed to action separately over a 200-mile front extending from Medjez el Bab in the north through the Ousseltia River Valley in the center to Gafsa in the south.

The main body of the 1st Division was still in the Ousseltia Valley on February 14, the date General Jurgen von Arnim’s Fifth Panzer Army launched a powerful offensive against U.S. II Corps positions in the Faid Pass area, 80 miles south of the division’s sector. Spearheaded by two panzer divisions, the Fifth Panzer Army advanced through and around Faid Pass to Sidi Bou Zid, where it mauled the American 1st Armored Division. Meanwhile, to the south, Rommel’s Panzer Army captured Gafsa and pushed north to effect a juncture with von Arnim at Kasserine Pass.

On February 16, the rest of the 1st Division was withdrawn from the Ousseltia Valley and dispatched to the Kasserine Pass vicinity to meet the enemy onslaught. The Germans pressed on. The two attacking armies, now united under Rommel’s overall command, reached Kasserine Pass on February 19. The next day the Germans launched a massive assault that broke through the Allied defense line. British troops and tanks and the U.S. 9th Infantry Division artillery were able to stabilize the situation and mount counterattacks that drove the enemy back. The Battle of Kasserine Pass effectively ended on February 23 when the Germans abandoned their offensive and withdrew eastward through the pass.

After Kasserine Pass, the 1st Division was sent to Marsott, northwest of Tébessa, to regroup. Following a 10-day rest, the division, assembled as a unit for the first time in the North African campaign, moved out of Marsott and deployed to attack the oasis town of Gafsa and its Italian garrison, taking the town without a fight on March 17. From Gafsa, motorized patrols probed in a southeasterly direction along the Gabès road, making contact with Italian forces just east of El Guettar. The division attacked the Italians on March 20, and a full-scale tank battle developed when the Germans rushed in strong reinforcements. After much hard fighting, the Germans broke off contact and withdrew from the El Guettar area on April 7.

The 1st Division moved by truck convoy 150 miles north to positions northeast of Beja. On the night of April 22-23, the division launched an offensive aimed at clearing the Tine River Valley and its flanking hills for the final drive on Tunis. The Tine Valley campaign was characterized by fierce fighting in rugged terrain that greatly aided the defenders. The division continued to attack and advance in a northeasterly direction until May 13, when the surrender of Axis forces in Tunis brought an end to the fighting in North Africa. Subsequently, the division was sent back to a training camp at Arzew.

With North Africa secured, the Allies turned their attention to Sicily. The invasion of that island, code-named Operation Husky, would involve Montgomery’s Eighth Army and the newly activated U.S. Seventh Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. George S. Patton. The 1st Division, part of General Omar Bradley’s II Corps, would land near the small port town of Gela, just west of Cape Passero on the south coast.

Preceded by airborne drops, the landings at Gela began at 2:34 am on July 10 with an attached ranger unit leading the way. The 16th and 26th Regimental Combat Teams followed a few minutes later. Italian units defending Gela offered only negligible resistance and were swiftly overcome. The German Luftwaffe, however, launched numerous raids against the invasion fleet and beachhead. One Stuka dive-bomber sank LST No. 313, loaded with elements of the 1st Division’s 33rd Field Artillery Battalion. On the afternoon of July 11, a large group of Ju-88s attacked the Robert Rowan, turning the ship into a funeral pyre for many of her crew and passengers when bombs ignited her volatile cargo of munitions and gasoline.

While Robert Rowan burned, the 1st Division beat back a powerful Axis counterattack spearheaded by the elite Hermann Göring Panzer Division. The attack came as the Americans were unloading their antitank guns and artillery from landing craft. The guns were hurriedly brought into action, and these plus the guns of Allied warships standing just offshore were soon pounding the onrushing panzers. Nevertheless, German tanks got to within 2,000 yards of the beach before they were repulsed.

After securing the Gela beachhead, U.S. forces drove through the western half of Sicily, capturing Palermo on July 23 and wheeling east to advance along the coast toward Messina. Throughout the campaign, the 1st Division was deployed on the right of II Corps in the island’s geographical center, fighting its way across mountainous terrain through Niscemi, La Serra, Caltagirone, Caltanisetta, and Enna. Following the capture of Nicosia on July 28, the division advanced to Troina, attacking the town on August 1 and clearing it of enemy troops five days later.

On August 17, U.S. troops entered Messina and linked up with British forces driving up along Sicily’s east coast. The city fell without a fight; the bulk of German forces had already fled across the Strait of Messina into Italy. The invasion of Italy would come soon, but the 1st Division would not be part of it. Instead, the division was sent back to England to begin training for the main event of the war in Western Europe: the invasion of the Continent code-named Operation Overlord.

Originally scheduled for June 5, 1944, the invasion was postponed until the next day because of inclement weather. Two U.S. Army corps were to take part in the Normandy invasion: VII Corps, which would land at Utah Beach on the southeast coast of the Cotentin Peninsula; and V Corps, which would land at Omaha Beach on the north coast of Calvados near Saint Laurent-sur-Mer. To the east, the British XXX and I Corps, consisting of British and Canadian forces augmented by various Allied units, were to seize three beaches code-named Gold, Juno, and Sword.

The assault by V Corps was to be spearheaded by two regiments landing abreast, the 116th Regiment of the 28th Division (attached to 1st Division ) and the 16th Regiment of the 1st Division. The 116th was to land on the right of the beach, while the 16th was to go ashore on the left. Each regiment would conduct the initial assault with two battalions landing abreast in columns of companies, with the 3rd Battalion companies coming in behind them. In all, nine companies, plus attached ranger units, were to land in the first wave.

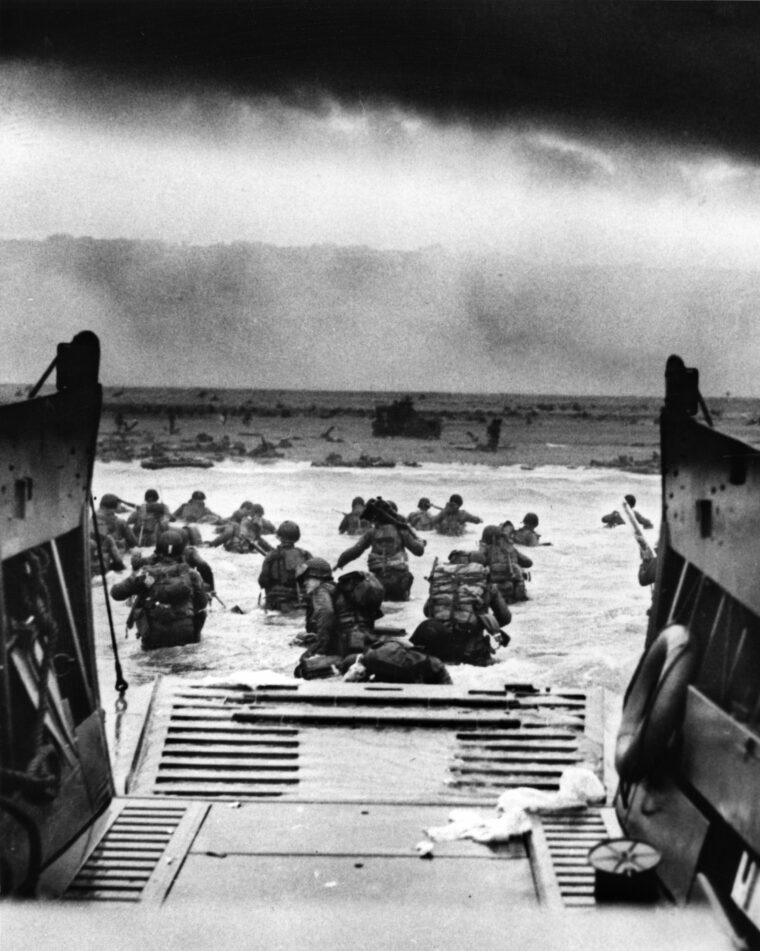

The landings began at 6:30 am. There was serious trouble from the start. Prior to D-Day, Omaha Beach was known to be a formidable objective, but even so, the difficulties encountered there went far beyond what Allied planners had anticipated. The German defenses, which consisted of an elaborate system of pillboxes, gun emplacements and connecting trenches, were situated behind the beach on a line of bluffs that rose to a height of 100 to 170 feet—an ideal place from which to oppose a seaborne onslaught. A low cloud cover obscured the target area from Allied aircraft and caused them to bomb wide of their targets. Preliminary gunfire and rocket support provided by a host of warships proved too inaccurate and too short in duration to do significant damage to German fortifications and beach obstacles.

As if this weren’t bad enough, a strong northeast wind had whipped up waves three to four feet high in the landing zone, and the rough water combined with the tidal current to wreak havoc on the approach to the beach. Armor support for the infantry was to have been provided by specially designed amphibious tanks, but most of these foundered on the run in to the beach, as did many of the DUKWs carrying the division’s artillery and ammunition. A number of troop landing craft were also swamped, while the majority of those that stayed afloat were driven leftward by the force of wind, waves, and currents.

In the ensuing confusion, the complex two-battalion assault plan quickly broke down. Companies I and L of the 3rd Battalion, which were to have landed in the first wave on Fox Green, went ashore late and too far to the east on Fox Red. As a result, the 16th Infantry’s initial assault was conducted solely by Companies E and F of the 2nd Battalion, with boat sections from these units landing alongside the 116th’s E Company, which was also out of position, on Easy Red between Saint Laurent and Colleville-sur-Mer and on Fox Green in front of Colleville-sur-Mer.

The assault troops debarked from their landing craft at distances of 100-200 yards from the shoreline, jumping off the ramps into rough water that was neck-deep in places and boiling with bullet and shrapnel blasts. After slogging through the surf to the water’s edge, the troops had another 200 yards of open sand to cross before reaching the dubious shelter of the sea wall or shingle bank. All the while they were subjected to withering artillery, mortar, and small-arms fire from German positions on the bluffs. Casualties were heavy.

The second group of assault waves began landing at 7 am to find the invasion apparently stalled on the shoreline. Movement off the beach occurred within the hour, however, and by mid-morning small groups were advancing up the bluffs. But the Germans still had the advantage and were resisting fiercely, so much so that when the 18th Infantry started to come ashore on Easy Red shortly after 10 am, the ownership of Omaha Beach was still undecided.

At a little after 1:30 pm, Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, commanding American forces from the cruiser Augusta, received a welcome radio message: “Troops formerly pinned on beaches Easy Red, Easy Green, Fox Red advancing up heights behind beaches.” This was already old news; by then, elements of the 1st and 28th Divisions had penetrated the enemy defense line at several points, with 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry, pushing inland beyond the bluffs to cut the coastal road that ran parallel to the shore.

Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry, began landing at about 6 pm on Fox Green; 1st Division’s command group came ashore an hour later on Easy Red. By this time, the 3rd Battalion, 16th Infantry had taken up a blocking position astride the coastal highway at Le Grand Hameau. As the day waned, 2nd and 3rd Battalions of 26th Infantry advanced inland across the coastal road between Saint Laurent and Colleville, while 1st Battalion moved in an easterly direction to take up positions in front of Caubourg.

Casualties for V Corps on D-Day numbered about 2,500 killed, wounded, or missing, with the two assaulting regimental combat teams (16th and 116th) losing about 1,000 men each. Many never made it to the shore. Paul Bystrak, a chief warrant officer in the division’s G-4 section who landed on Omaha Beach the next morning, remembered bodies floating in the water when they debarked from their landing craft. “The platoon of graves registration people were sort of frightened—they were hiding in foxholes and the bodies were floating in the waves, so we had to push our way through bodies to get to the beach. It was terrible.”

For all that, the Americans were firmly in possession of Omaha Beach. The other beaches, Utah, Gold, Sword, and Juno, were also secure. In all, over 150,000 Allied troops had gotten ashore by nightfall; and though it was not apparent at the time, the Germans were incapable of driving them back into the sea, much less containing them in their seaside lodgments. The campaign to liberate France had begun, and the 1st Division was destined to play an important role in it.

After D-Day the fighting shifted to Normandy’s hedgerow country, where the Allies found the going slow and bloody through the rest of June and July. In the final week of July, however, the Allies broke out of Normandy and the pace of events quickened dramatically. In August, Allied armies raced across France, subjecting the Germans to the same kind of blitzkrieg campaigns the enemy had used to conquer much of Europe three years earlier. During a three-day period in the last week of August, for instance, use of motorized transport and the rapid disintegration of German forces enabled the 1st Division to advance 96 miles across northern France, on a route that took the division through Alençon and Mamers to Courville-sur-Eure. The next day the division advanced east another 55 miles to bivouacs at Étampes.

On September 7 the division swung away from Mons and headed for Liège. Four days later, the division was across the Meuse River and driving toward the German frontier and the enemy’s Siegfried Line defenses. It seemed to many that the war might be over before the year was out. But it was not to be. The Germans still had a lot of fight left in them, as they proved in the months ahead.

The attack on the Siegfried Line began on September 12, with elements of the 3rd Armored Division breaking through three days later. On September 15, the 16th Infantry cut the roads leading southeast out of Aachen and continued to advance to the northeast, occupying a position in the Siegfried Line by nightfall. The division completed the encirclement of Aachen by October 10 and launched a direct attack on the city on October 12. Aachen was the first large city on German soil to come under attack by Allied ground forces. It was the ancient seat of Frankish kings, and the Franks were a Germanic people. The mighty Charlemagne, founder of the Holy Roman Empire, had made it his capital. To die-hard Nazis of the Third Reich, it was a sacred place. For that reason it had great symbolic value to Allies and Germans alike.

The battle for Aachen immediately degenerated into a bitter struggle that went from street to street and house to house. It lasted nearly three weeks. “Your fight for the ancient imperial city is being followed with admiration and breathless expectancy,” the German Seventh Army commander told the garrison. “You are fighting for the honor of the Nationalistic German Army.” The garrison finally surrendered on October 21. German honor had been satisfied, but the city had been destroyed in the process.

Following the capture of Aachen, the 1st Division moved southeast of the city to the Hürtgen Forest, with the aim of crossing the Roer River north of Düren and advancing to Cologne. Immediate objectives were the town of Gressenich and the Hamich-Nothberg ridge. On November 16, division elements attacked Gressenich; others advanced to Hamich and north and northeast along the line of Weh Creek and into the forest east of Schevenhütte. The battle for the Hürtgen Forest was under way.

The Hürtgen was not a natural forest. It was man-made, planted specifically as a defensive barrier. To the dismay of Americans who fought there, it fulfilled that role all too well. The Hürtgen Forest was as deadly, miserable, unrewarding, and relentless a battle as the 1st Division ever fought. The woods were treacherous, the mud thick and slimy. The roads were practically nonexistent. Casualties on both sides were heavy. Each house, hill, and hole in the ground was fought for, and gains were reckoned in yards, not miles.

Finally, the division pushed through the Hürtgen Forest toward the Roer River, capturing Luchem on December 4. Fighting began to slacken, and on December 7 the 1st Division was relieved by the 9th Infantry Division. Most 1st Division units were sent to Henri Chapelle, Belgium, southwest of Aachen; the 16th Infantry was quartered at Monschau .

The division’s respite was cut short by a massive German counterstroke in the Ardennes region on December 16. The attack, which developed into what is commonly known as the Battle of the Bulge, was directed against the northern portion of the broad front held by VIII Corps, between Monschau and Echternach. The enemy objective was to cut off the Allied supply port at Antwerp, Belgium, and capture the huge American supply dumps in the Liége, Verviers and Eupen areas. The 1st Division was just north of Eupen when the Germans attacked.

On December 17, the 26th Infantry was sent down from the Eupen area to Camp Elsenborn on the northern flank of the German breakthrough to contain the enemy drive and prevent it from spreading. The first elements of the 26th Infantry reached Camp Elsenborn early in the morning on December 17 and occupied Bütgenbach. Meanwhile, the 16th Infantry was on its way down from its bivouac area in the vicinity of Verviers to take up positions north of Weismes. The 18th Infantry remained just south of Eupen to deal with enemy paratroopers.

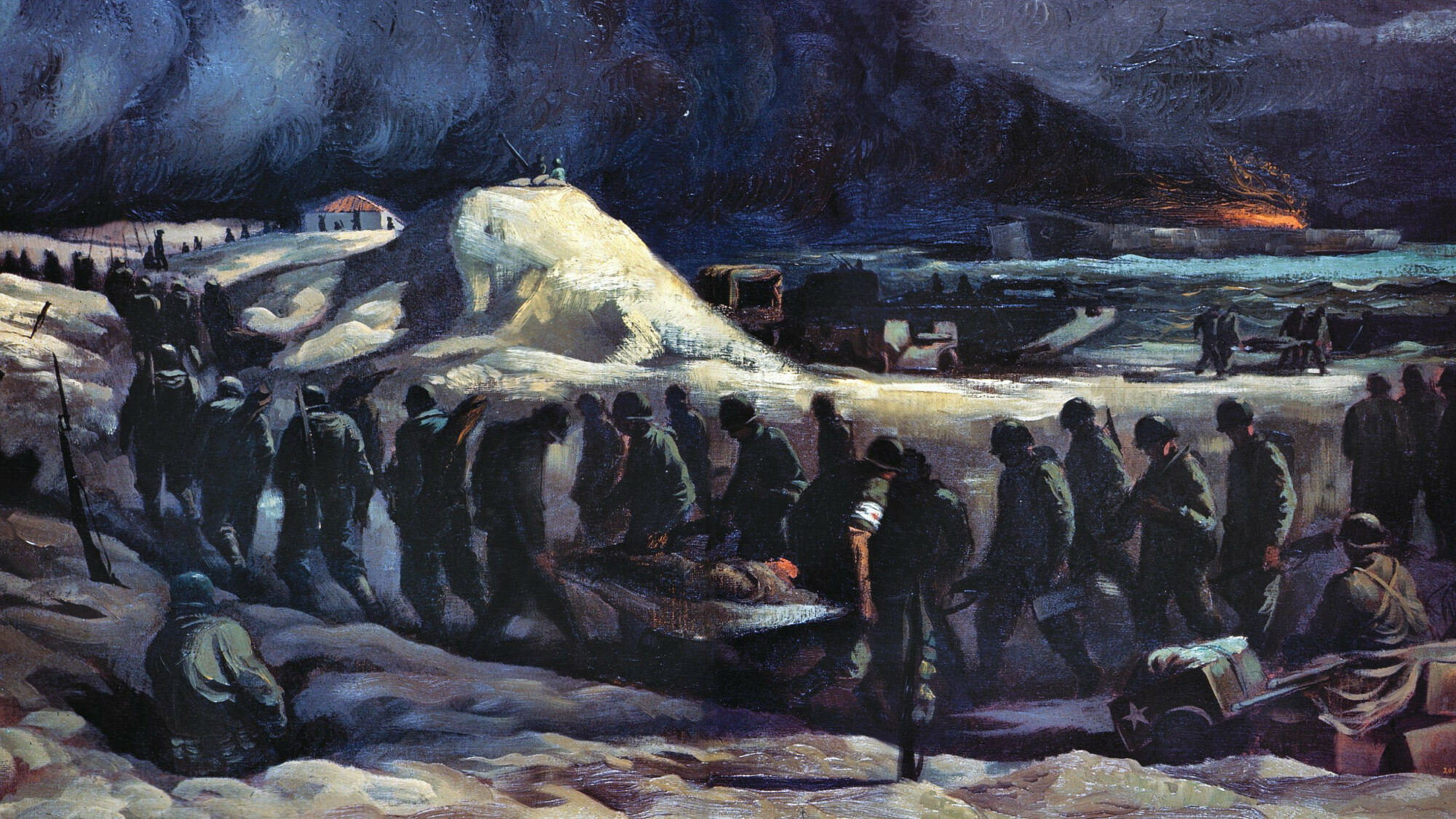

Between December 17 and 22, the Germans launched several attacks down the Büllingen-Bütgenbach-Weismes road, but none achieved the hoped-for breakthrough to the supply dumps at Spa and Verviers. After December 22, enemy offensive activity in the area abated. A stalemate ensued, with both antagonists being severely hampered by heavy snow and subfreezing temperatures. The Americans counterattacked on January 15, 1945, with the 1st Division being assigned the towns of Faymonville and Schoppen as its initial objectives.

By January 28, the Bulge had been eliminated and the 1st Division was attacking east toward the German border, seizing Mürringen, Hünningen, and Honsfeld on January 30. The next day the division took the high ground northwest of the Holzwarcke River. By February 3, elements of the division had once again penetrated the Siegfried Line. On February 5, three days after capturing Hollerath, the division was relieved by the 99th Infantry Division.

On February 8, the 1st Division (less Combat Team 16) moved to the forward assembly area to take over the defense of the Untermaubach-Bergstein-Grosshau sector. The division crossed the Roer River on February 25 and advanced rapidly to the Rhine. Between March 1 and 3, it fought for and captured Erp, and on March 8 it entered Bonn—too late to prevent the Germans from blowing up the city’s bridge across the Rhine. Bonn’s garrison formally surrendered to the division on March 9.

By the end of February, with American forces nearing the Rhine, the Germans began to demolish the bridges spanning the wide river. All but one were destroyed. At Remagen, the massive Ludendorff railway bridge remained miraculously intact. Dispatched to Remagen from Bonn, the 1st Division completed movement across the Ludendorff Bridge by March 16, one day before the weakened structure collapsed. Between March 16 and March 24, the division worked to enlarge the Rhine bridgehead and defend it against numerous German counterattacks. By March 25 the bridgehead was secure, and the way was open for the First Army to drive in force across the Rhine into the heart of Germany.

After March 27, the 1st Division advanced swiftly into Germany’s interior. On April 8 it crossed the Weser River and advanced toward the Harz Mountains, reaching the western slope on April 11. This move precipitated the collapse of enemy forces in the region. On April 18, the division was driving into the enemy’s rear areas, taking the high ground overlooking Blankberg and Thale on April 19. The next day, all significant German resistance had ceased.

The beginning of May found the division in Czechoslovakia, where it became embroiled in combat with a scratch force known as Division Benicke, made up of men from an officer candidate school in Milowitz. The 1st Division attacked this force on May 5, five days after Adolf Hitler committed suicide in Berlin. The division cleared the Drenice area and advanced down the road from Cheb to Falkenau on May 6, seizing several towns en route and liberating the Falkenau concentration camp. At the time of the German surrender, the 16th, 18th, and 26th Infantry Regimental Combat Teams, in conjunction with Combat Command A of the 9th Armored Division, were attacking toward Karlsbad.

At 8:15 am on May 8, the division received an order to cease firing at once and wait in place. Later that day, the division accepted the unconditional surrenders of Division Benicke as well as the 18,000 troops of the German XII Corps (Seventh Army) in the Chemnitz-Marienbad vicinity. The war with Germany was over.

The division would remain in Germany for another 10 years, first as an occupying force and then as an ally of West Germany. Returning to the United States in the summer of 1955, the 1st Division spent the next decade at Fort Riley, Kansas, during which time it became a mechanized formation. In 1965, the division was once again committed to battle, this time to in the rapidly escalating conflict in South Vietnam. There another generation of soldiers wearing the Big Red One patch on their sleeves garnered new battle honors and furthered the tradition of valor and victory so firmly established by their predecessors in World Wars I and II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments