By Robert L. Durham

German panzergrenadiers surrounded Hill 314 just east of Mortain in Normandy on August 7, 1944, trapping several companies of the 2nd Battalion of the U.S. 120th Infantry Regiment. Over the course of the next five days, as the Germans rained mortar shells and pounded their positions with direct fire from their deadly 88mm guns, the tenacious Americans held on.

Each time elements of the German 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division attempted to storm the rocky heights, the encircled Americans called in artillery fire to hold them off. At one point, the opposing sides were so close that an American officer called down artillery fire on his command post.

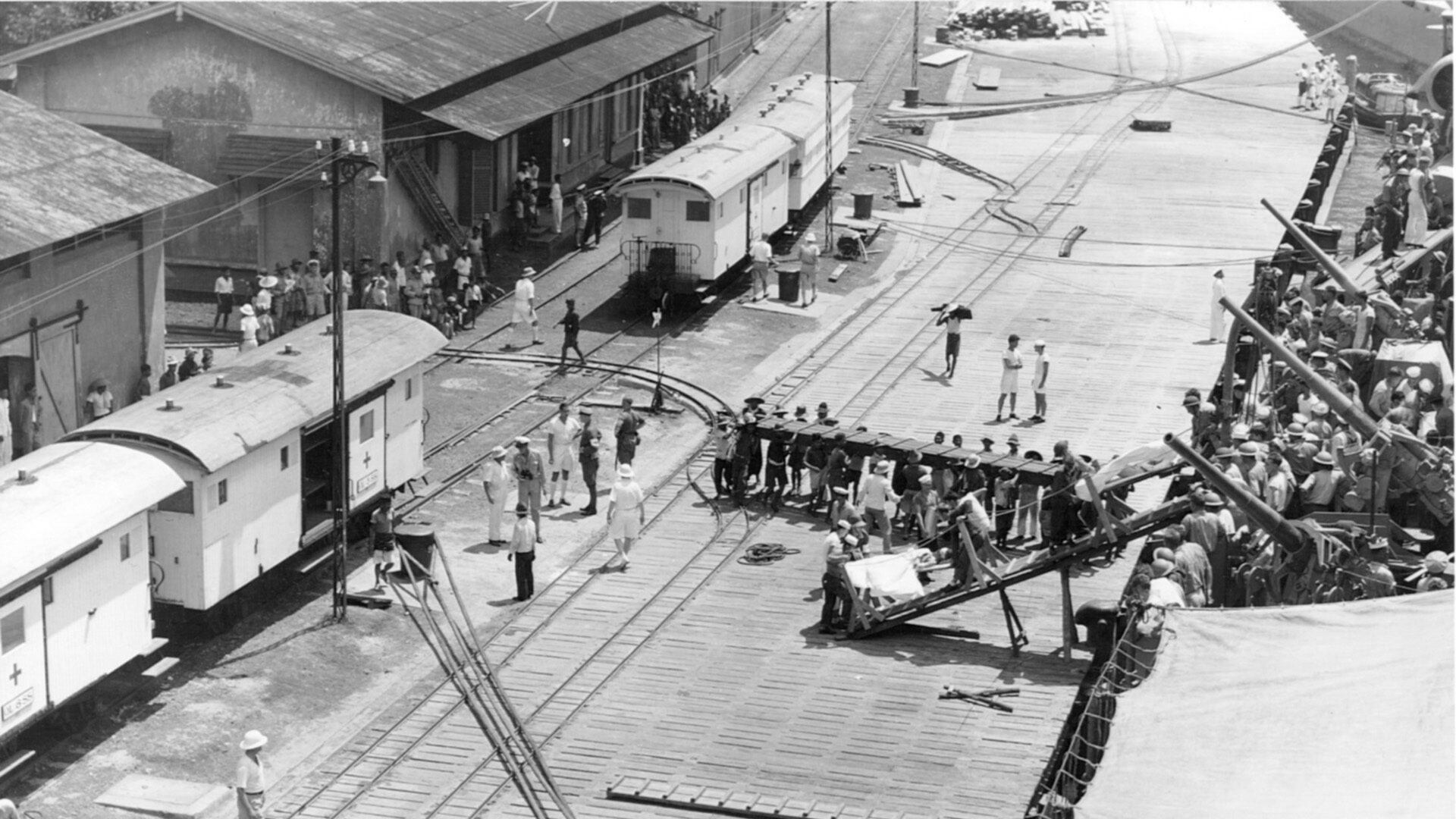

Throughout the ordeal the American soldiers trapped on the hill searched the bodies of their dead for food and ammunition before placing them in a makeshift morgue among the rocks. Various attempts were made to resupply them. U.S. artillery units even tried to fire shells filled with supplies to the hilltop, but the effort was an abysmal failure because the contents were either crushed or scattered over the hilltop. Supplies were also dropped from C-47s, but the parachutes often drifted into no-man’s land. After five days of bitter fighting, the Germans called it quits on August 12. Of the 670 officers and enlisted men defending the hill, the Americans lost 300.

Seven weeks after the D-Day landing, the Allies still had not pierced the German defensive line in Lower Normandy. The situation deeply frustrated the Allied senior leadership. At a heavy cost in lives, Lt. Gen. Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army had taken Caen on July 9 and Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley’s U.S. First Army captured Saint-Lo on July 18. The Wehrmacht leadership in Berlin, however, made a costly strategic error in holding the German 15th Army at Pas de Calais in anticipation of a second Allied landing in that sector. As a result, powerful reserves that might have strengthened SS Generaloberst Paul Hausser’s hard-pressed German 7th Army in Normandy remained unavailable.

To break out of their position, the Allies planned a two-stage assault on the German lines. The British and Canadians, under General Bernard Montgomery, would launch an armored assault west of Caen, in a attack code-named Operation Goodwood. Once the Germans were unbalanced by the British attack, the Americans would begin Operation Cobra to punch through the German line west of St. Lo and race 30 miles south to the road hub of Avranches at the southern end of the Cotentin Peninsula. Then, they would advance west from Avranches to secure the deep-water ports of Brittany. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, tasked Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, the commander of the First Army, with directing Operation Cobra.

Unfortunately for the Allies, Operation Goodwood failed on July 18-19. Thus, it fell to Bradley and his corps commanders to pierce the German line. Cobra called for concentrated bombing by hundreds of heavy B-17 and B-24 bombers, along with medium bombers and tactical bombers, of a narrow corridor west of St. Lo followed by a six-division attack by Maj. Gen. Joseph Lawton Collins’ VII Corps.

Some elements of VII Corps had participated in the D-Day landings, while others had come ashore as reinforcements in the days following the invasion. The VII corps actually belonged to Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army, which had not yet been activated, but Bradley attached them to the First Army for the battles in the hedgerows of Normandy. Supporting Collins in Operation Cobra would be Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps, positioned west of Collins’ command.

Poor coordination between air and ground forces during the saturation bombing missions on Monday July 24, combined by heavy cloud cover, led to friendly fire casualties. Bradley had issued orders that the assault battalions poised to exploit the bombardment should only pull back 1,200 yards, while the margin of safety usually required was 3,000 yards from the bomb line. Some of the bombs fell at 2,000 yards, resulting in 25 killed and 131 wounded.

In contrast, the Germans suffered modest losses of 350 casualties and 10 destroyed armored vehicles that day. After the bombardment, Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein, the German Panzer Lehr Division commander, advanced his forward outposts in the mistaken belief that the Americans had concluded their saturation bombing.

Dissatisfied with the aerial bombardment, Bradley agreed to let Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory unleash his strategic and tactical bombers on the Germans again the following day. The aerial bombardment on Tuesday, July 25, devastated Bayerlein’s Panzer Lehr Division. The division lost 2,000 men, which amounted to more than half of its fighting strength. What is more, the bomb strikes destroyed the division’s communications network. Kampfgruppe Heintz, which was stationed outside the bombing zone, was the only operational element that remained of Bayerlein’s elite panzer division.

Unfortunately, the Americans again suffered friendly fire casualties when some of their bombs fell short of their targets. They lost 111 killed and 490 wounded as a result of their own munitions. Among the dead was Lt. Gen. Lesley McNair, the head of Army Ground Forces, who ordinarily sat behind a desk in Washington, D.C., but that day was visiting the front lines.

The VII Corps’ assault began shortly before Noon on July 25. Collins had assembled 120,000 troops on a five-mile front along the Saint-Lo-Periers Road. The attacking infantry were supported by 600 artillery pieces.

On the right side of Collin’s line of battle, the attack by the U.S. 9th Infantry Division bogged down in hard fighting against veteran fallschirmjagers of Parachute Regiment 13 of the German 5th Parachute Division. The Americans clawed their way through the first layer of the German defense, but got no further that day. Meanwhile, on the left side of Collin’s line Maj. Gen. Leland Hobbs’ 30th Infantry Division captured the shell-torn village of Hebecrevon.

A regiment of the U.S. 4th Infantry Division attacking in the center ran headlong into a German defensive position made up of some of the few tanks of the Panzer Lehr Division that had escaped destruction in the aerial bombardment that morning. The Americans defeated them with bazookas and M4 Sherman tanks. But at the end of the first day, the offensive had not met its objectives. Tasked with driving the Germans back three miles, the Americans had pushed them only a mile beyond the Saint-Lo-Periers Road.

U.S. forces moved faster on the second day as infantrymen riding on tanks jumped off to spray every thicket or wood they passed. The 1st Division averaged less than three minutes to clear each hedgerow, something that took hours a few weeks earlier.

On Wednesday, July 26, the Americans attacked in the direction of Marigny. Combat Command B of the 3rd Armored Division led the way but bogged down as heavy traffic and cratered roads slowed its advance. Yet the U.S. tank crews could move cross-country through the tall hedgerows of the Normandy’s bocage terrain more easily than the Germans. This was because they had outfitted their Sherman tanks, nicknamed “Rhinos,” with prongs welded from German beach obstacles to enable them to slice their way through the hedgerows. Lacking such equipment, the German panzers had to stick to the roads.

At that point the reserve of the 2nd Armored Division reinforced CCB. A German kampfgruppe of 30 panzers and armored fighting vehicles, which included a powerful Hummel self-propelled gun mounting a 150mm cannon, tried to capture a strategic crossroads near Notre-Dame-de-Cenilly. A company of American armored infantry, backed by several Sherman tanks, held the crossroads throughout the night repulsing the determined German counterattack.

Meanwhile, a column of 15 PzKpfw IV tanks from the 2nd SS “Das Reich” Panzer Division and 200 paratroopers from the 6th Parachute Regiment attempted to overrun an American outpost held by a company of the 4th Infantry Division. Two batteries of American M7 Priest self-propelled guns and four M10 tank destroyers held back the enemy assault until they were reinforced by an armored infantry company. Once reinforced, the Americans forced the Germans to withdraw.

Thunderbolts went into action again on the afternoon of Thursday, July 27, swooping down on 500 German vehicles packed tightly together as they sought to escape south. By nightfall, the P-47s had destroyed 122 tanks, 259 other vehicles, and 11 artillery pieces in the Roncey Pocket 20 miles southwest of Saint-Lo. Another air strike by British Typhoons armed with 20mm cannon destroyed nine tanks and 28 vehicles.

Other sharp clashes erupted throughout the night as German troops tried to escape encirclement by slipping through gaps in the American lines. As many as 1,000 German infantrymen, supported by various armored vehicles, attempted a breakout near St. Denis-le-Gast, but the Americans shattered them. Lt. Col. Wilson Coleman, the commander of the 41st Armored Infantry of the 2nd Armored Division, won a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross for his role in the fighting.

On Friday, July 28, Major General Robert Grow’s 6th Armored Division of Middleton’s VIII Corps, advanced down the main road to Coutances. Three miles to the east, the Maj. Gen, John Wood’s 4th Armored Division traveled on another road toward Coutances. The debris of German columns that had been annhilated by Allied fighters blocked their way.

Up to this point in Operation Cobra, the Germans had offered very little resistance. By nightfall the Americans had passed through Coutances and were well on their way south to their objective of Avranches. The Germans retreated hurriedly south through the lower Cotentin Peninsula in trucks and horse-drawn wagons. The P-47s maintained steady pressure on the retreating enemy throughout this time. On Saturday, July 29, lead elements of the 4th Armored Division entered Avranches, only to find it undefended. The liberated French inhabitants greeted them with cheers and by waving the French tricolors.

Two days later the VIII Corps took 7,000 German prisoners. The demoralized enemy did not even have to be escorted into captivity. The U.S. GIs simply disarmed them and pointed to the rear. “We face a defeated enemy, an enemy terribly low in morale, terribly confused,” Patton told the officers of the 4th Infantry Division.

Bradley then turned the VIII Corps over to Patton. He summoned “Old Blood and Guts” to his headquarters to inform him that he would activate his Third Army on August 1. Patton’s objective would be to clear the Germans from Brittany. Bradley also elevated Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges to command of the First Army. Bradley, however, retained overall command of both the First and Third armies in his capacity as commander of the Twelfth U.S. Army Group.

Patton set off at once for Coutances to direct the movements of Middleton’s VIII Corps. It did not take long for Patton to make his presence known. When Patton observed some soldiers in his command digging foxholes, he rebuked them. “It is stupid to be afraid of a beaten enemy,” he shouted.

The spearhead of the 6th Armored Division forced a crossing of the Soulle River west of Coutances on July 29. Once on the south side, 6th Armored’s CCA met only modest resistance. Over the next two days, Middleton’s troops brushed aside enemy resistance as they advanced south along the Atlantic coastline. The German front had all but collapsed, though some pockets continued to fight hard. The VIII Corps began mopping up the resistance as it pressed towards Avranches.

The Germans realized that the Allies were poised to invade Brittany, and they moved to secure a strategic bridge over the Selune River south of Avranches before the Americans could get there. But the Sherman tanks of the 4th Armored Division crossed the bridge first and checked the German advance. After a brief exchange of gunfire, the Germans retreated to St-Malo. The American 4th and 6th Armored Divisions captured 4,000 German prisoners, and the infantry following them took an additional 3,000 prisoners into captivity.

Patton met with the staff of the Third Army on July 31. First, he told them that the army would begin its advanced toward Brittany the next day. Second, Patton told them that during their advance not to concern themselves with protecting their flanks. “Flanks are something for the enemy to worry about,” he said “We’re going to kick the hell out of him all the time, and we’re going to go through him like crap through a goose,” said Patton.

Middleton’s VIII Corps advanced into Brittany on August 1, while Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip’s XV Corps of the Third Army swung east for Le Mans, which was where the headquarters of the German Seventh Army was located. Patton drove the VIII Corps forward relentlessly in order to capture Brest, Lorient, St. Malo, and Quiberon.

After capturing these cities, Patton wanted to swing his army to the east where he intended to encircle German forces facing the British and Canadians at Caen, but his ambitious plan had not yet been embraced by Eisenhower, so it remained only an idea. Patton had to be doubly sure to follow the chain of command and obey his superior officers in the wake of his disgraceful conduct in Sicily in August 1943 where he had slapped soldiers of the Seventh Army under his command.

Patton’s lead elements advanced into Avranches on August 1. Once inside the city, he needed to funnel two armored divisions and two infantry divisions, which amounted to 100,000 men and 20,000 vehicles, across a single bridge. This called for a traffic cop, not a general. But when Patton arrived in the city, he began directing the columns of troops himself. For several hours, he stood in the middle of the traffic jam, directing convoys to the cheers of passing soldiers.

Patton initially had issued orders directly to his division commanders without apprising his staff, but he soon realized it was to his benefit to turn everything over to his staff and have them work out schedules and routes. Elements of Patton’s armored spearheads got lost on the first night and had great difficulty determining the correct route in the dark. Enemy artillery and bombers made their advance even harder. Despite the congestion they encountered at intersections, CCA and CCB both arrived at their objectives, St-George, and St-Hilaire-du-Harcourt, respectively, south of the Selune River at dawn.

Middleton found serving under Patton much different than serving under Bradley. Patton advanced boldly, while Bradley had advanced cautiously. When Middleton submitted detailed and cautious plans of action to his new commander, Patton flatly rejected them.

Patton knew from intelligence reports that the German forces in Brittany had scant armor and artillery. Therefore, his soldiers had no reason to fear counterattacks. If his troops encountered pockets of resistance, they were to bypass them and allow follow-on forces to mop up behind the advancing armor. “Old Blood and Guts” only concerned himself with reports the Germans would attempt to destroy key bridges and dams before his troops could reach them. He therefore tasked Brig. Gen. Otto Weyland, the commander of the XIX Tactical Air Command, with deploying fighter aircraft to guard the critical infrastructure in Brittany until it was secured by his ground troops.

Patton claimed he had a “sixth sense” that enabled him to know with moral certainty what the enemy was going to do. He estimated that there were not more than10,000 Germans in the Breton peninsula, but he would soon learn that he was way off the mark. The Germans actually had 60,000 troops garrisoning the peninsula.

Patton ordered Grow to take Brest and push on without worrying about any other objectives. On the same day, he received orders from his superiors to take Brittany with the smallest number of troops possible. Consequently, Patton shifted the XV and XX corps under his command to the east. This left just Middleton’s VIII Corps to capture all of Brittany.

Patton ordered Grow to bypass enemy resistance and advance as quickly as possible to Brest. In so doing, Patton overrode Middleton’s orders to his division commanders to first take Saint-Malo on the English Channel and then pivot south to Dinan before marching 125 miles west to Brest on the western tip of Brittany.

The American P-47s did not get into the sky until late in the afternoon of August 1. They knocked out German anti-tank guns hidden in hay wagons, as well as three 88mm flak guns. Using Allied intelligence gleaned from Ultra intercepts, the 6th Armored Division’s two combat commands advanced 45 miles in two days. American fighters patrolled far ahead of the armored columns, guarding them as they sped toward their objectives in Brittany. In order that they would not be mistaken for German panzers, the American tank crews placed large brightly colored panels on the tops of the vehicles to make identification easier.

The advance guard of 6th Armored entered Mauron on August 3 where one of its platoons encountered small arms and cannon fire. The platoon engaged the enemy while the rest of the company encircled the town from the north. They knocked out several machinegun nests, compelling the enemy to quit the town.

CCA of the 6th Armored encountered a destroyed bridge at Pontivy the following day. Sergeant Malcolm Helton of the 68th Tank Battalion’s reconnaissance platoon searched the surrounding area and discovered an alternate route over the river and canal for which he received a Bronze Star. This enabled the combat command to keep to its schedule. The column advanced more than 60 miles beyond Mauron. This concluded “one of the most daring, brilliantly led, under-pressure armored stabs made thus far in the march,” wrote Lieutenant Robert J. Burns Jr., author of the battalion’s official history.

The combat commands continued westward toward Brest. When they reached Huelgoat, which was 75 miles east of Brest, they met heavy resistance. German troops armed with Panzerfausts set one of their tanks ablaze, but the crew remained inside continuing to fire their machinegun. When the heat became unbearable, they exited the tanks to find themselves amid Wehrmacht troops who ordered them to surrender. The tank crewmen refused and immediately opened fire on the Germans. Machinegun fire killed two of them immediately. Technician 4th Grade Charles E. Pidcock continued to fire his sub-machinegun at close range until his tank exploded throwing him into a hedgerow. He miraculously survived the ordeal. The Army awarded all three tank crewmen the Silver Star.

The 6th Armored Division reached the outskirts of Brest on August 6. CCB assaulted the Brest defenses at dawn, but the Germans drove them back. After a day of being shelled by German artillery, Grow became convinced a major assault would be required; however, he knew it would take at least two days to mass enough force to capture the Atlantic port. He sent a messenger under a white flag to demand the Germans surrender, but the German commander refused to capitulate.

On the road to Brest, the 68th Tank Battalion encountered repeated roadblock set up by the Germans. The fire teams manning the roadblocks typically had a mix of mortars, panzerfausts, machine guns, and small arms. In one such encounter, Lieutenant John Lundh led a section of tanks in an assault that forced the Germans to retreat to the far end of a town. While CCA of the 6th Armored Division bypassed the enemy, Lundh’s section knocked out two enemy machinegun nests, inflicting heavy casualties. Both of his tanks were destroyed in the assault, though. The Germans destroyed Lundh’s tank with direct fire from a 75mm, and they destroyed the other tank with panzerfausts.

On August 7 CCA, under constant fire from German artillery, advanced 32 miles passing through the towns of Bodilis and Plabennec. The following day the advance guard of the 6th Armored Division found itself under heavy attack from German artillery and mortars. The armored vehicles ground to a halt when they ran out of fuel. They had travelled so far and so fast their supply lines were overextended. At that point, American observation aircraft arrived, but the spotters could not locate the German positions because they were superbly camouflaged. For the next four hours, the Americans had to endure shelling from hidden German artillery pieces.

Despite the shelling, the Americans were on the final approaches to Brest. The men were exhausted, having travelled nearly 250 miles in recent days. But they were to have no rest. Grow ordered them to prepare to take the city. The exhausted soldiers considered assaulting such a strong position tantamount to a suicide mission.

While Grow organized his division for the attack, German troops in pockets of resistance that had been bypassed, attacked his supply lines. The Americans captured a German staff car coming from Brittany’s northern coast. The Germans in the staff car had been reconnoitering the American positions outside Brest in preparation for a counterattack. Inside the staff car was the commander of the German 266th Infantry Division. Grow ordered an immediate attack on the 266th Division, who would not have the benefit of their captured commander. The attack was a resounding success, and the Americans destroyed the German division.

On the morning of August 9, American artillery softened up the German positions on the outskirts of fortress Brest. Grow scheduled the assault for 7 a.m. German 20mm flak guns held up the advance for a while, but American howitzers soon silenced the German guns.

As the attack progressed, the various armored task forces worked their way as close as possible to the German defensive positions. Task Force Davall, led by CCA’s Lt. Col. Harold Davall, had started to outflank the Germans when he received orders to break off the attack and regroup.

Task Force Davall redeployed to Plouvien, which was 10 miles north of Brest. The reconnaissance platoon of the task force cleared the enemy from the town. The task force then entered the town. While preparing to bivouac for the night, the Americans heard firing erupt in the streets of the town. It turned out that 1,500 men of the German 265th Infantry Division had arrived in Plouvien unaware that the Americans had arrived in the town at the same time. Captain Raymond Polk, the commander of Able Company, took a section of Sherman tanks and engaged the Germans, but his assault was stopped cold by the well-armed Germans.

Based on intelligence reports, Grow decided to press on with the original attack. Captain Polk would lead a task force whose objective was to outflank the Germans. Sherman tanks advanced against the enemy’s right flank. When the enemy realized they were being assaulted from two sides, they withdrew from the town while being strafed by P-47s. For his tactical victory, Polk received the Silver Star.

Patton ordered Grow not to waste time besieging Brest, but to leave a screening force to pin the Germans inside the garrison and then move the bulk of the 6th Armored Division south to capture Lorient and points beyond it. Although he had failed to capture Brest, Patton had rendered the German forces in the interior of Brittany incapable of launching a counterattack against the rear of the Allied forces moving east towards Paris.

Meanwhile, Patton tasked Middleton with bottling up the German garrison at Saint-Malo. For the task at hand, Middleton had only one task force of cavalry scouts and tank destroyers. To assist Middleton, Patton sent Maj. Gen. Robert C. Macon’s 83rd Division.

The Germans defending Saint-Malo were led by Oberst Andreas von Aulock, a veteran of the Battle of Stalingrad and the commander of the German 79th Infantry Division. He had 12,000 Germans with which to defend the fortress, and had vowed to fight to the last stone. They faced 20,000 Americans.

Desperate fighting in the streets occurred over the course of two weeks beginning August 4. While the ground forces battled inside the city, American fighters sank two German warships and blasted concrete bunkers in the harbor. The Germans systematically demolished the port’s infrastructure and set fire to the city before withdrawing to a fortified position on the outskirts of the city.

The Nazis, who had strong positions in camouflaged underground pillboxes, continued to resist. In the end, American artillery scored direct hits on most of the German artillery and machinegun emplacements, giving the enemy no choice but surrender, which they did on August 17. “A platoon of captured Germans started singing farewell to their commander,” recalled Private Frank Reichmann of the 331st Infantry Regiment. “Most of them were in tears.”

Meanwhile, it took three American divisions totaling 75,000 men to capture Brest on August 25. As they had at Saint-Malo, German demolition squads destroyed the vital port facilities and most of the city. Thus, the Germans succeeded in rendering the deep-water ports in Brittany useless to the Allies. But in the final analysis, the campaign in Brittany would prove to be of little strategic consequence because its ports were too far away from the battlefront. No Allied cargo ships or troop ships ever used Brest and American engineers never built a port at Quiberon as Eisenhower had initially planned.

At the same time Grow raced toward Brest, Wood’s 4th Armored Division fought its way toward Rennes. Patton received intelligence that the Germans had been ordered to destroy the supply dumps at Rennes, so he pressed Wood to reach the city as quickly as possible.

Mistaking one of Wood’s columns for the enemy, Patton ordered Weyland to destroy the column with his strike aircraft. Fortunately, though, the lead pilots recognized Wood’s Sherman tanks and waved off the air assault. The air command flew ahead of the column and knocked out several German 88mm batteries.

On August 2, Wood’s division arrived at Rennes and found it heavily defended by the Germans. Patton ordered Rennes bypassed, and ordered an advance on Lorient. The Germans set fire to the supply dumps in Rennes the next day and withdrew. Fifteen German tanks counterattacked on August 4, but that did not stop Wood’s lightning advance. The American fighters dealt with the German armor. Wood’s division captured Vannes on the Bay of Biscay on August 5, thereby cutting off the last escape route for the remaining German forces in Brittany.

Later that day Wood pushed on to Lorient, but the large German garrison in the U-boat base stopped his advance. The same thing occurred at the U-boat base at Saint-Nazaire further south. Wood asked Middleton for permission to take Nantes on the River Loire, and received the go-ahead. Colonel Bruce Clarke’s CCA raced 80 miles to the city, to find the Germans were in the process of destroying their supply dumps and bases. After French Resistance fighters showed Clarke a safe path through the enemy lines, Wood gave Clarke permission to storm the city. In a matter of hours, the 4th Armored Division had taken control of the major city at the mouth of the Loire River.

Middleton’s VIII Corps had by that point achieved the majority of its objectives, although the Germans still held Lorient and Saint-Nazaire. Wood’s armored division screened the two cities for a week until relieved by Grow’s division. In late August other forces relieved the 6th Armored Division, which released the VIII Corps’ armored forces for the advance to Germany.

While the VIII Corps advanced into Brittany, the rest of Patton’s Third Army had turned toward Le Mans, which lay 110 miles east of Avranches. Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division of Collins’ VII Corps captured Mortain, which was situated 20 miles east of Avranches. It continued on through the town and Hobbs’ 30th Infantry Division then took possession of the town. The American presence reassured the civilians, who wildly cheered the Americans and threw flowers.

A rugged hill east of Mortain, Montjoie, offered a fine lookout point. The GIs called it Hill 314 after its height in meters. Soldiers of the 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment, were sent to the top, along with Lieutenant Robert L. Weiss, an artillery forward observer for the 230th Field Artillery Battalion.

German leader Adolf Hitler had ordered four panzer divisions to counterattack in a desperate bid to retake Avranches. The plan called for the panzer formations to strike east through Mortain to Avranches. Hitler intended for the counterstrike to drive a wedge between Patton’s Third Army and Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ First Army.

At 1 a.m. on August 7, 26,000 German infantry and 300 panzers advanced toward Mortain and the 30th Infantry Division’s positions around the village. By starting their attack at night, the Germans avoided taking an immediate beating from the American P-47s. For the Germans, nothing seemed to go right. Of the six attacking German columns, only three moved forward on schedule, and one consisting of the 116th Panzer Division on the German right did not advance at all.

The German assault fell heaviest against the U.S. forces around Saint-Barthelemy, a crossroads town two miles north of Mortain. Opposing armor blazed away at each other at close range. Meanwhile, American infantry lay in waiting for panzer grenadiers following the German armor.

The American GIs held their ground for six hours, destroying 40 panzers. At Abbaye Blanche, a 66-man platoon armed with bazookas and artillery forced an entire SS regiment to retreat. Other American GIs took out 60 panzers. When the fog burned off in the morning, though, P-47s went into action, as did Allied howitzers. The Germans found the punishment from aircraft and artillery unbearable.

But the veteran German armored divisions had experienced similar challenges on the Eastern Front, and they remained undaunted. Some German armored forces made impressive progress even though the odds were heavily stacked against them. For example, the 2nd Panzer Division advanced four miles in the north, and the 2nd SS Panzer Division fought its way into Mortain.

On Hill 314, the situation was desperate. Lieutenant Weiss called in fire missions, starting at dawn and firing only by sound and map coordinates. Germans fought their way up the east and south slopes of the hill simultaneously. Weiss called in artillery strikes against these close-range targets. The enemy responded with mortar and direct fire from 88mm anti-aircraft guns.

The German advance ground to a halt when American artillery, directed from the observes on Hill 314, paralyzed it. The artillery fire prevented the units on the 30th Division’s southern flank from collapsing under the weight of the German assault. White phosphorus shells forced German panzer grenadiers into the open where they were then blasted by high-explosive shells. By nightfall on the first day the German attack had stalled. Although the Germans heavily outnumbered the Americans, they could not force their way through the 6,000 soldiers of the 30th Infantry Division.

On August 8, the Allied aircraft and artillery pounded German positions mercilessly throughout the day. “We must risk everything,” Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge told his staff, even though he knew the battle was lost. Hitler, though, demanded that von Kluge renew the attack, although the Germans remained 20 miles from Avranches.

Von Kluge established a new kampfgruppe, the redoubtable Generalleutnant Heinrich Eberbach, the commander of the German 5th Panzer Army. The Germans sent an SS officer up Hill 314 under a flag of truce to demand the surrender of the American forces on the hill. When Lieutenant Ralph Kerley sent the SS officer on his way with a stream of profanity, the Germans hurled everything they had at the Americans entrenched on the hill.

The situation on Hill 314 was grim. Slain GIs were laid in a make-shift morgue among the rocks so they would not be visible to the other defenders, but nothing could hide the smell. Although multiple attempts by various means were made to replenish the ammunition of the troops on Hill 314, all attempts failed.

With the situation stalemated, the Germans ultimately quit offensive operations at Mortain on August 12 and began withdrawing east. A relief regiment from the 35th Division climbed to the top of Hill 314 and carried down 300 casualties; however 370 walking wounded were able to make it down on their own. The 30th Division had suffered 1,800 casualties and other units together experienced almost as many. Bradley subsequently ordered Patton to shift his forces to Le Mans, which Patton captured on the same day.

In the breakout from Normandy, Patton had demonstrated the value of his armored tactics. Eisenhower, Montgomery, and Bradley all saw the possibilities offered by releasing Patton’s Third Army for a race to the Seine River. This would allow the Allies to roll up the flank of the enemy force in Normandy. The Germans would maintain a healthy respect for Patton and his Third Army through the duration of the war in Europe.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments