By Al Hemingway

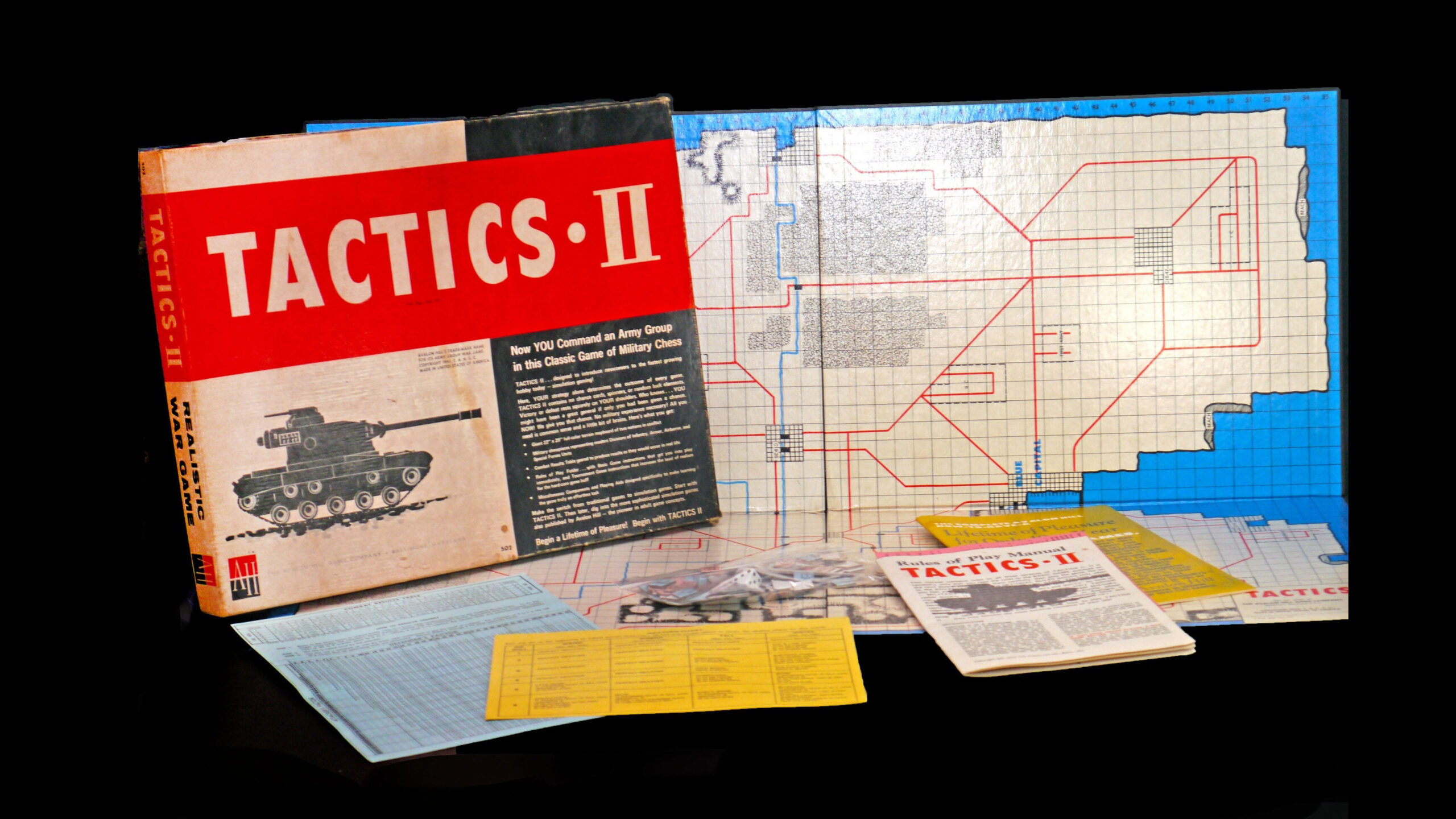

On a March day in 1939, a 40-man combat patrol from the Japanese Kwantung Army, led by Major Tsuji Masanobu of the operations staff, made its way to the base of Changkufeng Hill, a 450-foot-high mountain located on a ridge line near the Tyumen River in Manchuria. For several years, the Soviet Union and Japan had argued over the border that separated Mongolia from Manchuria. The Japanese had established a puppet government in Manchuria known as Manchukuo after they invaded that country in 1931. Since that time, border incidents had arisen between the two nations vying for eminence in the region.

In the summer of 1938, the Soviet Union and Japan fought a bitter two-week battle that resulted in a Soviet victory and their occupation of Changkufeng Hill. The defeat was a humiliating one for the Japanese Sixth Army—and they were determined to avenge it.

On Tsuji’s order, his entire patrol stood and urinated in front of the Soviet positions on that March day, much to the amusement of the Russian soldiers. Then, Tsuji’s men sat and ate a lunch complete with saké, traditional Japanese rice wine. What appeared to be a day in the park was actually a serious effort on Tsuji’s part to gather intelligence on the terrain and take photographs of the area for an upcoming Japanese assault to drive the Red Army from the region. The bloody struggle that would follow near the tiny hamlet of Nomonhan would result in the opening shots of World War II.

In his new book, Nomonhan, 1939: The Red Army’s Victory That Shaped World War II (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 288 pp., maps, notes, index, $31.95, hardcover), author Stuart D. Goldman has not only written a powerful account of the Red Army’s lopsided victory over Imperial Japan but also included the impact the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact had on the war, paving the way for Hitler to invade Poland a few days after hostilities at Nomonhan had ended.

Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, always the shrewd politician, waited patiently as Japan invaded China before making a major move in the area. As the mushrooming Chinese fighting sapped Japan of its manpower, weapons, and aircraft, including units from their Manchurian occupation force, Stalin reinforced the garrison in Manchuria, placing General Georgi Zhukov in command of the forces there.

In July, the Japanese assaulted the Red Army’s positions. Soviet artillery pounded the Japanese as Red Army infantrymen from two battalions reinforced by armored vehicles finally pushed the attackers back to their starting point. That August, Zhukov ordered a major counteroffensive that decimated the Japanese 23rd Division. Once again Soviet artillery hammered Japanese positions and the newly arrived T-34 tanks annihilated the Japanese armor. In the end, an estimated 18,000-23,000 men were killed and wounded, not counting the troops in Manchukuo engaged between May and September 1939. Most of the Kwantung Army’s guns and tanks had been destroyed along with about 150 aircraft. Soviet and Mongolian losses were heavy as well, with more than 30,000 dead and wounded.

The Japanese severely underestimated the fighting capabilities of the Soviet troops and their state-of-the-art equipment, mistakes they would continue to make throughout the war. They erroneously believed that the superiority of the individual Japanese soldier would be the deciding factor in any battle they fought. Meanwhile, the Soviet military walked away from Nomonhan having learned many important lessons that they would put to their advantage when battling the German Army in the years ahead, mainly in the area of tank-infantry warfare.

As the author points out, even though the border clashes occurred nearly 75 years ago, their repercussions are still felt today. When Japan signed the peace treaty ending World War II on September 2, 1945, the Soviet Union was not included in the pact. Now, in the 21st century, both countries continue to view each other with a wary eye as the ghost of Nomonhan lingers.

Survivor of Buchenwald: My Personal Odyssey Through Hell by Louis Gros and Flint Whitlock, Cable Publishing, Brule, WI, 2012, 229 pp., photographs, index, $24.95, hardcover.

It is hard to fathom that the word Buchenwald, name of the infamous Nazi concentration camp outside Weimar, Germany, means “beech forest” in German. It was here 100 years earlier that the noted German poet Johann Wolfgang Goethe sat under the shade of a massive oak tree to think. A little more than a century later, Goethe would have been sickened to see how his idyllic spot had been transformed into a living hell on earth by the Nazis.

Louis Gros was a French Catholic who was with the Maquis, or French Underground, when he was arrested in 1942. After months in prisons, he was transported to Buchenwald and miraculously survived to tell his story of the horrors that were perpetrated against its inmates.

Because he was not Jewish, Gros soon found himself working in the armament factory situated near the camp, which he describes as a “lucky assignment for any inmate.” His father, who was also incarcerated at Buchenwald, was assigned to work at a nearby factory as well. Gros and other inmates worked on an assembly line for the V-2 rocket. Many of these workers would sabotage the rocket components in hopes that they would fail. Getting caught meant certain death.

Gros vividly describes the stench of burning flesh that permeated the air within the prison. The one unmistakable feature that dominated the landscape was the smokestack for the crematorium where inmates, especially the Jews, were sent every day. Gros escaped death on many occasions, including once when an air raid by American bombers killed many of his fellow prisoners. He was liberated by elements of General George S. Patton’s U.S. Third Army as they raced after the Germans. He spent years fighting tuberculosis, which he contracted while a prisoner. He has gone on to live a productive life since his incarceration but, as he writes, “The memories are always there….”

The Color of War: How One Battle Broke Japan and Another Changed America by James Campbell, Crown Publishers, New York, 2012, 481 pp., notes, bibliography, $28.00, hardcover.

This book follows the paths of several Marines and black seaman, culminating with the victory at Saipan in the Pacific Theater and the disaster at the Port Chicago Naval Ammunition Depot near San Francisco that killed and injured hundreds of sailors—most of them black. Both occurred in July 1944.

As the author states, black seaman who enlisted in the U.S. Navy prior to World War II were confined to mess duty. In 1942, at the urging of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, blacks were finally allowed to join the armed services and to be given the same assignments as white servicemen. Unfortunately, most officers did not agree with the order, and the military remained segregated until 1948.

Promised education and better choices of jobs in the military, most blacks found themselves relegated to menial and, at times, dangerous tasks, such as handling ammunition at Port Chicago. The horrific detonation of shells resulted in a huge work stoppage by blacks, who insisted that the assignment was too

hazardous to perform. Fifty men were charged with mutiny and, if found guilty during time of war, could have received the death penalty. All the defendants were found guilty but given prison terms. Almost all were released by early 1946.

The Battle of Saipan and the concurrent Battle of the Philippine Sea, according to U.S. Naval historian Samuel Eliot Morrison, expended a tremendous amount of ammunition. Because of this, the Port Chicago facility was forced to handle large amounts of shells to replenish the supply and, as the author writes, “It was ill-equipped to handle such an onrush of ordnance.”

This is a well-written account of two vastly different events that, incredibly, were linked together by the war. The Port Chicago incident and the subsequent mutiny and trial created a furor in black America. Civil rights advocates called for equality and justice in the military—something that would not become a reality for another two decades.

Battle Ground Pacific: A Marine Rifleman’s Odyssey in K/3/5 by Sterling Mace and Nick Allen, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2012, 352 pp., maps, photographs, $25.95, hardcover.

Here is one of the best memoirs written about one man’s experiences in two of the worst battles fought by U.S. forces in World War II. Sterling Mace, a wisecracking kid from New York City, enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps after Pearl Harbor and was assigned as a BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) man with Company K, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division shortly after its return from the Cape Gloucester campaign. The unit’s next assault was on the island of Peleliu, a claw-shaped Japanese fortress in the Palau chain. The purpose of the operation was to seize the island and construct an airstrip to guard General Douglas MacArthur’s right flank as he advanced toward the Philippines. Despite the optimistic predictions of taking the island in four days, the Marines and the U.S. Army’s 81st Division required more than two months. Sadly, the operation could have been cancelled because MacArthur’s path to the Philippines was never in jeopardy from the Japanese.

From the moment the ramp lowered on Mace’s landing craft at Orange Beach 2 on September 15, 1944, until the completion of the three-month battle for the island of Okinawa in the spring of 1945, the New York native escaped death on numerous occasions and survived the horrendous ordeal. Mace and co-author Nick Allen do a marvelous job of relating the everyday life of an infantryman in combat and his growing up on the streets of the Big Apple.

Mace’s unit was featured in the HBO miniseries The Pacific. It chronicled Eugene Sledge, a mortar man with K/3/5, fighting on Peleliu and Okinawa. Sledge later wrote about his experiences in the classic book With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa, one of the best personal accounts dealing with men in combat.

Mace, who was a consultant on Sledge’s book, has also delivered a hard-hitting story that equals Sledge’s memoir.

Final Victory: FDR’s Extraordinary World War II Presidential Campaign by Stanley Weintraub, Da Capo Press, Philadelphia, 2012, 256 pp., photographs, notes, index, $26.00, hardcover.

Historian Stanley Weintraub has penned another engrossing work dealing with the only American president to serve more than two terms—Franklin Delano Roosevelt. This book focuses on FDR’s campaign for his fourth term in office, winning hard-fought election only to die less than three months later. Roosevelt had not been in good health. His heart was failing, and the polio he had contracted (a carefully hidden secret from most of the American public) years earlier was taking its toll. Still, most Americans wanted FDR to have another term. With the war still raging in Europe and the Pacific, they believed he was the man to finish the job.

The Republicans had their hands full to find a candidate to beat the popular FDR. They chose Thomas E. Dewey, the dapper governor of New York who, as Weintraub writes, had a “mechanical smile.” Despite that physical drawback, the savvy New Yorker was a consummate politician and came out swinging, criticizing FDR.

In the end, although he mounted an aggressive campaign, Dewey was defeated by FDR, who took most of the electoral votes and 36 of the 48 states. Sadly, the rigors of the campaign trail took their toll, and FDR passed away in April 1945. Vice President Harry S. Truman was sworn in as the new commander-in-chief.

“There will never be another fourth-term election,” Weintraub writes. “The Rooseveltian legacy may be that we will never have further crises of such magnitude as to require one.”

A Different Time, A Different Man: The Story of John L. Sullivan, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for FDR and Truman’s Secretary of the Navy by Stephen Clarkson, Peter E. Randall Publisher, Portsmouth, NH, 2011, 233 pp., photographs, index, notes, $24.95, hardcover.

Once described as a “dynamo,” the feisty John L. Sullivan played a key role as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration and, arguably, his most important part as Harry Truman’s Assistant Secretary of the Navy during the postwar years when the U.S. defense budget was slashed and there was talk of combining the armed services.

A skillful politician, Sullivan, a New Hampshire native, was a staunch advocate of war bonds during World War II to help pay for the escalating cost of the war effort. An extremely intelligent man who “kept his finger on the financial pulse of the country,” Sullivan commented in October 1943, “Nearly every activity of the Government cuts across my desk sooner or later.”

During the years following the war, Sullivan became Secretary of the Navy when the National Security Act was enacted in 1947. It was during these lean years that Sullivan not only fought for the construction of new ships but also battled to maintain the Navy in its present state and prevent the abolishing of the Marine Corps.

Clarkson, who was Sullivan’s law partner for 13 years, has done a superlative job on his biography. The book highlights the numerous accomplishments of a dedicated American who was an advocate for fiscal responsibility and a strong defense for the country while never once sacrificing his integrity.

Short Bursts

Road to Valor: A True Story of World War II Italy, the Nazis, and the Cyclist who Inspired a Nation by Aili and Andres McConnon, Crown Publishers, New York, 2012, 336 pp., photographs, notes, index, $25.00, hardcover.

All that Gino Bartali ever wanted to do was ride his bicycle. In fact, the native of Tuscany in northern Italy became a renowned cycling legend when he won the Tour de France, a grueling 2,200-mile excursion that winds its way through the Alps, in 1938. With his victory, the Fascist government of Benito Mussolini attempted to use Bartali’s win for propaganda purposes, something that thoroughly sickened the champion.

Although apolitical, Bartali had no choice but to take sides when Italy capitulated and the country was occupied by the Nazis during the war. He became involved with the Italian resistance movement and would routinely ride through the countryside carrying forged documents, photographs, and other papers, in the frame of his bicycle. Through his efforts, he saved the lives of an estimated 800 Italian Jews.

After the war Bartali was poor and practiced vigorously for another attempt at winning the Tour de France, which he did in 1948. Often outspoken and irascible with reporters because of his views, they soon dubbed him Ginettaccio or “Gino the Terrible.”

A quiet and unassuming man, Bartali rarely discussed his wartime experiences. On May 5, 2000, surrounded by his family, Bartali quietly passed away. Called Ginettaccio by some because of his hard demeanor, he was called a hero by many for risking his life to save the lives of others—and that is what true heroes do.

The Kissing Sailor: The Mystery Behind the Photo That Ended World War II by Lawrence Verria & George Galdorisi, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 224 pp., photographs, notes, index, $23.95, hardcover.

Times Square. New York. August 1945. Japan had just surrendered to the Allies, ending nearly four long years of war.

Pandemonium erupted as people flocked to read the Times “zipper” announcing the end of hostilities. Greta Zimmer, a dental assistant dressed in her white uniform, stared intently at the marquee as she read the exciting news. Suddenly, George Mendonsa, a sailor serving aboard the destroyer USS The Sullivans, grabbed the startled dental assistant and, holding her tightly, gave her a big kiss.

Unknown to the embracing pair, LIFE magazine photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt saw the opportunity for a good shot and quickly raised his camera, snapping four pictures in succession. The second picture would grace the cover of the publication and go on to become one of the most celebrated photographs of the World War II era.

However, Eisenstaedt did not get the couple’s names. It took years of detective work and investigating numerous claims by others saying that they were the kissing couple on that August day to finally uncover their identity.

The authors not only do a great job in following the clues that led to the undisputable claim that Mendonsa and Zimmer are, in fact, the kissing couple, but they also convey the euphoria that swept the country when the war ended.

It has been immortalized for eternity in one simple photograph.

A Man and His Ship: America’s Greatest Naval Architect and His Quest to Build the SS United States by Steven Ujifusa, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2012, 464 pp., photographs, notes, index, $29.99, hardcover.

William Francis Gibbs was a dreamer. Although painfully shy, he went on to become one of the greatest engineers and created, with his brother, a gigantic shipbuilding empire that produced some of the finest ships constructed during World War II.

At times irascible and demanding, Gibbs required excellence from his employees, especially his engineering staff and draftsmen. From his austere offices in New York City, Gibbs’s staff designed a new cargo ship that FDR dubbed an “ugly duckling.” The new vessel, however, would soon be known to the American public as the “Liberty Ship,” one of the most significant vessels of the conflict. On June 6, 1944, Gibbs requested that his staff “make a short prayer,” for the thousands of GIs storming the beaches at Normandy in the landing craft his company had designed. But it was not until after the conflict that Gibbs finally realized his dream of constructing the SS United States, the fastest and most elegant ocean liner to date, launched in 1952.

This book commemorates the 60th anniversary of the maiden voyage of Gibbs’s oceanic masterpiece, the SS United States, often called “the greatest ocean liner ever built.” It is also a tribute to the tenacity and determination of one man to see his dream through to reality.

Pacific Commandos: New Zealanders & Fijians in Action: A History of the Southern Independent Commando and First Commando Fiji Guerrillas by Colin R. Larsen, Hailer Publishing, St. Petersburg, FL, 2012, 161 pp., maps, photographs, $29.99, softcover.

Written in 1946, this book had been out of print for more than 60 years prior to being re-released. Although small in number, these behind-the-lines raiders, who also included within their ranks Solomon Islanders and Tongans, provided valuable intelligence to Allied units during the war.

Led by New Zealanders, the unit was created in 1941 and served in numerous campaigns in the Solomon Islands, including Guadalcanal. When the unit was disbanded in 1944, more than 40 percent of its officers and 30 percent of its noncommissioned officers had lost their lives. Every man in the unit had contracted malaria and had been pushed to his physical limits. For their courageous actions, many of the men were decorated. Kudos to the publisher for shedding some well-deserved light on the Fiji Commandos

of World War II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments