By John Walker

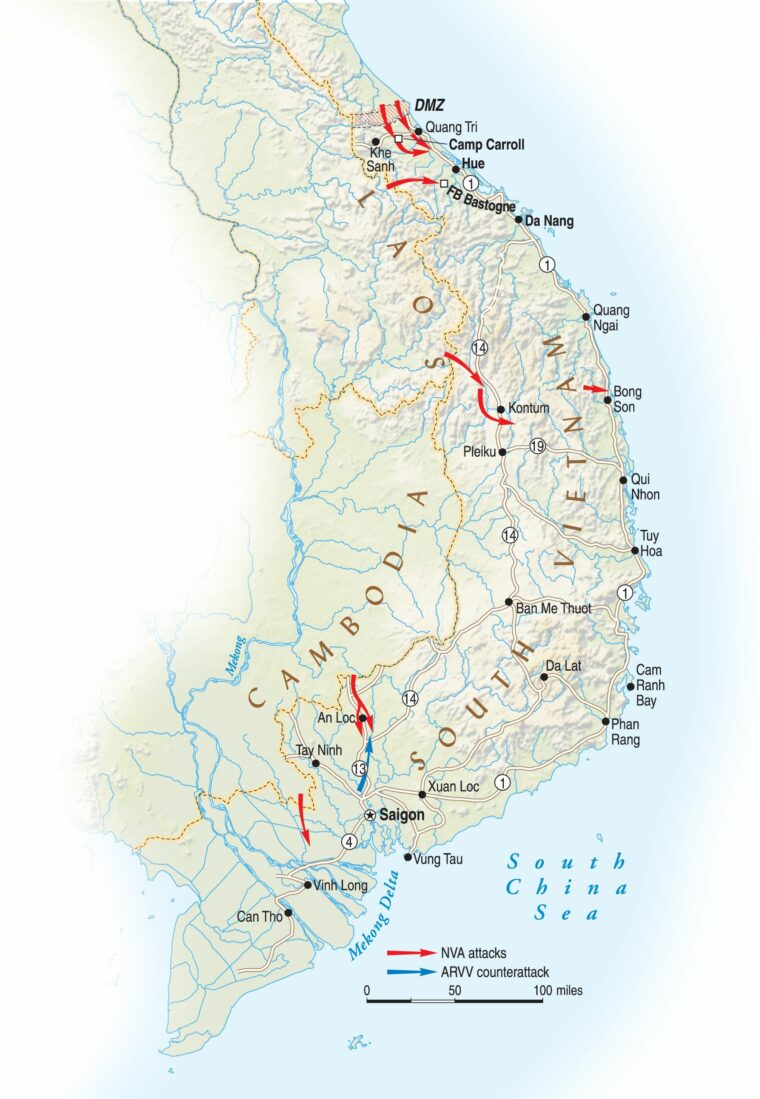

At noon on Good Friday, March 30, 1972, more than 25,000 North Vietnamese Army (NVA) soldiers, backed by state-of-the-art Soviet tanks, artillery, and mobile antiaircraft missile platforms, poured across the Demilitarized Zone separating the two Vietnams. The NVA troops attacked a string of South Vietnamese-held firebases just below the border in Quang Tri Province. Within hours the outnumbered troops of the inexperienced 3rd Infantry Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) fell back in the face of the Communist onslaught. Two more Communist divisions rolled south across the DMZ in follow-up attacks, while another division, supported by an armored regiment, crossed the Laotian border and attacked from the west toward Hue City.

One week later, three combined NVA-Viet Cong divisions crossed the Cambodian border and drove into Binh Long Province to threaten the towns and airfields of Loc Ninh and An Loc, a provincial capital 65 miles northwest of Saigon. On April 12, three additional NVA divisions attacked the cities of Pleiku and Kontum in the Central Highlands in an effort to cut South Vietnam in two.

Just as they had done during the infamous Tet invasion in 1968, when the attacking force was made up almost entirely of Viet Cong insurgents, the North Vietnamese Politburo again had gone all-in, committing 14 infantry divisions and 26 separate regiments—some 120,000 men—backed by 1,200 armored vehicles, long-range, heavy-caliber artillery, and antiaircraft missiles. Almost every available Communist combat unit in North and South Vietnam and Laos switched over from protracted guerrilla tactics to combined-arms conventional operations.

By the spring of 1972, Vietnamization, a process by which all American troops would be withdrawn from Southeast Asia while the ARVN was left to fight the war on its own, was almost complete. American in-country strength had fallen from its peak of 550,000 to just 70,000 troops, of whom only 6,000 were combat soldiers. The only American ground units left in South Vietnam were the 196th Light Infantry Brigade at Da Nang and the 3rd Brigade of the 1st Air Cavalry Division (Airmobile) at Bien Hoa.

The large and complex U.S. intelligence, communications, and logistics structure in South Vietnam had been dismantled, and virtually all American-built bases had been turned over to the ARVN, which lacked the means to secure and maintain them. With the advent of Vietnamization, the ARVN had to do some major shifting of units to cover strategic regions; one of these areas was along the DMZ, where ARVN soldiers and South Vietnamese marines were stretched dangerously thin. In mid-1968, some 45 allied infantry battalions had been deployed in South Vietnam’s two northernmost provinces, Thua Thien and Quang Tri. By 1972, with American infantry gone, only 21 South Vietnamese battalions occupied the same area. Artillery strength and ammunition supply rates in the northern region had suffered a similar decline.

In early 1972 the ARVN deployed the newly activated 3rd Infantry Division, comprised mostly of green troops, along the DMZ in 13 firebases formerly occupied by American Marines. Of the division’s three regiments, only the 2nd Regiment, recently transferred from the battle-tested 1st ARVN Division, had combat experience. The 56th and 57th Regiments were made up of local force units upgraded to division status, filled out by recaptured deserters and convicts, and officered by cast-offs and incompetents. The NVA attack on March 30 caught the 3rd Division changing position. Hundreds of ARVN soldiers were caught in the open as shells began raining down. Supported by 200 tanks and self-propelled artillery on a scale never before seen in the war, the Communists crossed the border along the Ben Hai River and pushed south into Quang Tri Province.

On April 1, after heavy fighting, Brig. Gen. Vu Van Giai, the 3rd Division commander, ordered a retreat, instructing his troops to set up a new line on the Cua Viet and Cam Lo Rivers, anchored on Camp Carroll, an artillery firebase halfway between the Laotian border and the coast. On April 2, Colonel Pham Van Dinh, commander of the 56th ARVN Regiment, surrendered Camp Carroll, its 2,000-man garrison, and 22 intact artillery pieces without a fight.

The NVA advance toward their initial objective, Quang Tri City, was slowed by ARVN delaying actions and liberal applications of American air strikes and naval gunfire from U.S. Navy 7th Fleet ships on station in the Gulf of Tonkin. On the morning of April 27, the Communists advanced again, launching multi-pronged attacks against Dong Ha (which fell the next day) and advancing to the outskirts of Quang Tri. Beginning a withdrawal from that city, Giai’s units collapsed after receiving conflicting and confusing orders from I Corps commander Lt. Gen. Hoang Xuan Lam, a political general who had performed poorly during an abortive ARVN drive into Cambodia in 1971.

Ordered to conduct a general retreat to the My Chanh River, ARVN columns were hit hard as they fell back. To the south near Hue, Fire Support Bases Checkmate and Bastogne were lost after bitter fighting. The exodus of ARVN forces was joined by tens of thousands of South Vietnamese civilians fleeing south toward the dubious safety of Hue City. As the mass of humanity jostled and shoved its way south on Highway 1, it presented an inviting target for NVA artillerists and infantrymen. NVA formations captured Quang Tri City on May 2. That same day, South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu replaced Lam with Lt. Gen. Ngo Quang Truong, one of the ablest and most experienced commanders in the ARVN. Truong’s arrival immediately lifted the spirits of the troops under his command tasked with holding Hue and reestablishing ARVN defenses.

Although the initial fighting in the north had proven disastrous for the ARVN—in one month of battle, the South Vietnamese in Military Region I had lost almost all their artillery and all but one of their American M-48 tanks—staunch defensive efforts in other areas, combined with massive American air support, inflicted extremely heavy casualties on NVA attackers.

The Communist attack in the Central Highlands developed more slowly, but by April 24 NVA forces had destroyed the ARVN 22nd Division at Tan Canh and Dak To, seized control of northern Kontum Province, and were knocking on the door of Kontum City. Thieu removed another corps commander, essentially leaving the senior civilian American adviser, John Paul Vann, in command of Military Region II as Kontum City braced for an all-out assault.

Farther to the south in Military Region III, realizing too late that the main attack was developing in Binh Long, not Tay Ninh Province, the South Vietnamese and their American advisers were slow to reinforce the corridor down Highway 13. Loc Ninh fell to the 5th NVA Division after a week of fighting. A few days later, Communist infantry and armor invaded An Loc’s northern neighborhoods and could not be ejected. American commander General Creighton Abrams cabled Washington in early May that Saigon had lost the will to fight and the war might soon be lost.

The Communist forces that attacked Pleiku and Kontum consisted of the NVA 320th and 2nd Divisions in the highlands and the 3rd Division in the coastal lowlands, approximately 50,000 troops. Arrayed against them were the ARVN 22nd and 23rd Divisions, two armored cavalry squadrons, and the 2nd Airborne Brigade, all under the command of Lt. Gen. Ngo Dzu. The preparatory attacks in Binh Dinh Province, long a Communist stronghold, threw Dzu into a panic and almost convinced him to divert his forces from the highlands. Vann reassured Dzu that it was only a ruse and advised him to remain ready for the main blow, which Vann was convinced would come from western Laos. Vann began working day and night, utilizing his extensive civilian and military contacts to channel American support (especially airborne) to the region. To counter the threat from the west, Dzu deployed two regiments of the 22nd Division to Tan Canh and Dak To and two armored squadrons to Ben Het.

On April 12, the NVA 2nd Division, elements of a tank regiment, and several independent regiments attacked the outpost at Tan Canh and the nearby firebase at Dak To. When ARVN armor moved out of Ben Het toward Dak To, it was ambushed and wiped out. Overwhelmed, the South Vietnamese defense northwest of Kontum quickly disintegrated, placing the South Vietnamese high command in a quandary. With the rest of the 22nd Division covering the coast, there were few forces left to defend the provincial capital of Kontum. Inexplicably, the North Vietnamese advance halted for three crucial weeks. While the crisis calmed, however, Dzu began to unravel. Vann gave up all pretext of South Vietnamese command and took over himself, placing responsibility for the defense of Kontum on the shoulders of Brig. Gen. Ly Tong Ba, commander of the 23rd Division. Vann then utilized massive B-52 strikes to hold the North Vietnamese at arm’s length and reduce their numbers while he managed to find additional troops to stabilize the situation.

On May 14, the North Vietnamese reached the outskirts of Kontum and launched their main assault. The 320th Division, two regiments of the 2nd Division, and elements of the 203rd Tank Regiment attacked the city from three directions. The city mustered a defense force that consisted of the 23rd Division and several Ranger groups. Their three-week delay, probably due to the need for resupply, cost the attackers dearly.

By May 14, the worst of the fighting in other sectors had passed, and American B-52s were free to concentrate on the Central Highlands area. During the Communist attack, the positions of the 44th and 45th ARVN Regiments crumbled and were overrun, but a well-placed B-52 strike landed directly on the NVA attacking force at the point of the breakthrough. The next morning, when ARVN troops returned to their former positions unopposed, they discovered 400 enemy bodies and seven destroyed tanks.

At Vann’s insistence, Thieu replaced Dzu with Maj. Gen. Nguyen Van Toan, whose outwardly confident and assertive nature was the complete opposite of Dzu’s. For the following two weeks, massive NVA assaults were lashed by B-52s and helicopter gunship attacks. ARVN troops then counterattacked over the remains of the attacking waves. On May 26, four NVA regiments supported by armor managed to punch a hole in the Kontum defenses, but their advance was halted by U.S. helicopters firing new tube-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided (TOW) missiles. In three days, 23 North Vietnamese T-54 tanks were destroyed by TOWs and the breach was sealed.

With the aid of the American and South Vietnamese air forces, the ARVN managed to hold Kontum during the remainder of the battle. By early June, the North Vietnamese had faded to the west, leaving behind over 4,000 dead on the battlefield. U.S. intelligence later estimated that total NVA losses in the Central Highlands sector during the offensive totaled between 20,000 and 40,000 killed and wounded. Vann did not have time to savor the victory, however. While returning to Kontum from a briefing in Saigon on June 9, he was killed in a helicopter crash.

On April 4, reacting to the fierceness of the offensive, American President Richard Nixon authorized tactical air strikes from the DMZ north to the 18th Parallel, the southern panhandle of North Vietnam. This interdiction effort was the first systematic bombing carried out in North Vietnam proper since the end of Operation Rolling Thunder in November 1968. Air strikes north of the 20th Parallel began on April 5, and the first B-52 strike of the new operation was conducted on April 10. Nixon then upped the ante even further, targeting the cities of Hanoi and Haiphong.

Between May 1 and June 30, B-52s, fighter-bombers, and fixed-wing gunships carried out 18,000 sorties over North Vietnam. On May 8, Nixon ordered the aerial mining of Haiphong harbor and other North Vietnamese ports to half the flow of Chinese and Soviet supplies necessary to sustain the offensive in the south. Nixon gambled that the Soviet Union, with whom he was conducting negotiations for a strategic arms limitation treaty, would withhold a negative reaction in return for improved relations with the West. The People’s Republic of China also muted any overt response for the same reason. Emboldened, on May 10 Nixon launched Operation Linebacker, a systematic aerial assault on North Vietnam’s transportation, storage, and air defense systems. The operation significantly impeded the NVA’s ability to sustain its offensive by severing supply routes into North Vietnam and preventing reinforcements from entering the South.

The North Vietnamese had seriously underestimated American technological progress in weapons systems since the end of Rolling Thunder and the resolve of a different American commander-in-chief to use them. Nixon’s desire to rescue South Vietnam depended on the growing strategic mobility of American air power. As the crisis unfolded, several hundred U.S. Air Force combat aircraft were rushed to Southeast Asia from scattered bases in Thailand, where they were joined by five U.S. Navy aircraft carriers.

The massive impact of U.S. B-52 bombers and AC-130 gunships was especially valuable in devastating North Vietnamese formations, as was naval gunfire along the coast. Often overlooked, courageous U.S. Air Force cargo pilots and crews delivered essential supplies in the face of deadly enemy fire. In North Vietnam, laser-guided bombs delivered by USAF strike forces inflicted unprecedented damage on key targets. Sizable numbers of precision-guided munitions—“smart bombs”—were being employed for the first time. American warplanes used wire-guided bombs to destroy North Vietnamese bridges that had withstood years of attack by conventional ordnance. The bombing continued for the next six months.

When the Easter Offensive began, the only South Vietnamese division operating in Binh Long Province was the 5th ARVN Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. Le Van Hung, while the 25th ARVN Division manned firebases along the border with Cambodia in neighboring Tay Ninh Province to the west. On April 2, the 24th and 271st NVA Regiments attacked the firebases using tanks, rockets, and mortars. Although earlier intelligence reports had indicated the North Vietnamese were preparing for offensive operations in Military Region III, comprised of the 11 provinces surrounding Saigon, South Vietnamese leaders continued to insist wrongly that the main attack would come in Tay Ninh Province, near the Cambodian border.

In the early morning hours of April 5, the NVA launched a major armor-supported attack in Binh Long Province against the city of Loc Ninh, a district town located on highway QL-13, halfway between An Loc and the Cambodian border. As fighting escalated, Lt. Gen. Nguyen Van Minh, Military Region III commander, and Maj. Gen. James Hollingsworth, Minh’s American adviser, determined that the attacks in Tay Ninh were a mere diversion and that the main focus of the Communist attack would come in Binh Long Province. Although Hollingsworth directed all tactical air support in support of the hard-hit garrison, inflicting heavy casualties, the NVA’s superior numbers eventually overwhelmed the defenders. Repeated human wave attacks overran the ARVN positions in Loc Ninh late on April 7.

The North Vietnamese plan for taking An Loc—encircling the city, cutting Highway 13 south of the city to prevent its reinforcement, destroying the ARVN forces in An Loc, and the use of the city for a follow-on attack against Saigon—involved three main force NVA divisions. The elite 9th NVA/VC Division targeted An Loc, the 7th NVA Division moved to stop supplies and reinforcements from reaching An Loc from Saigon, and the 5th NVA/VC Division was to join the 9th Division in attacking An Loc after Loc Ninh was secured.

Shortly after the fall of Loc Ninh, the 9th Division made its initial move against An Loc by seizing the airstrip at Quan Loi, two miles northeast of the city. Meanwhile, south of An Loc, the 1st ARVN Airborne Brigade, moving up from Saigon, pushed north up Highway 13 from Lai Khe to reinforce the An Loc garrison. The ARVN paratroopers immediately ran into heavy elements of the 7th NVA Division, which was entrenched in blocking positions along the highway. The reinforcements were stopped in their tracks. The subsequent loss of the airstrip and the obstruction of Highway 13 meant that An Loc was surrounded. If An Loc fell, nothing stood between the NVA and Saigon.

Early on the morning of April 13, NVA gunners hit An Loc with artillery, mortars, and rockets. Just after dawn, Communist forces began a coordinated tank and infantry attack from the northeast, advancing on the town through a deluge of rockets, bombs, and napalm delivered by Allied aircraft. When Soviet-made T-54 and PT-76 tanks attacked down the main north-south highway into An Loc, panic ensued among the ARVN defenders, who had never encountered tanks. Several units broke and ran before an ARVN infantryman calmed the situation by knocking out one of the lead tanks with an M-72 Light Anti-tank Weapon.

Heavy fighting raged for three days as NVA soldiers advanced from house to house. Casualties were heavy on both sides. By the third day, NVA attackers had lost 23 tanks but had forced the defenders into a small redoubt in the southern sector of the city. The critical factor holding back the North Vietnamese thrust was U.S. air support, coordinated by American advisers serving with the ARVN ground forces while U.S. attack aircraft, AC-130 gunships, and Cobra helicopters worked in close support. Hollingsworth called in B-52 strikes against the enemy’s staging areas in the rubber plantations surrounding the city. The vital air support during the three days of pitched fighting saved the ARVN from almost certain defeat.

Despite the continued pounding from the air, the Communists succeeded in completely encircling the city of An Loc. They then began shelling the city heavily, firing 25,000 artillery rounds and rockets during the first three days, then firing between 1,200 and 2,000 rounds per day into the city for another week as they regrouped for another attack. On April 16, Minh ordered the 1st Airborne Brigade to assault the high ground southeast of the city. At the same time, he ordered the newly arrived 21st ARVN Division, which had been operating in the Mekong Delta, to attack north up Highway 13 to relieve An Loc.

The NVA’s plan to overrun An Loc no later than April 20 had failed. Their next attempt would come from the east. The 9th Division would again conduct the main thrust against the city, with elements of the 5th and 7th NVA/VC Divisions launching supporting attacks against ARVN positions southeast of the city. To counter U.S. air support, the Communists moved forward additional antiaircraft weapons, including Soviet-made SA-7 Strella shoulder-fired, heat-seeking, surface-to-air missiles.

A massive predawn artillery bombardment on An Loc and the 1st Airborne Brigade positions southeast of the city signaled the start of the NVA’s second attempt to capture the provincial capital. The attackers overran one battalion and drove the other two into the city. The main attack against An Loc did not fare as well. ARVN defenders and American advisers continued to fight off repeated armor-supported human wave attacks. With the aid of continuous air support, the defenders held their positions. By the second day, NVA attacks had abated.

Conditions inside the city deteriorated. As the Communists continued to pour a withering amount of 100mm tank gun, rocket, mortar, and artillery fire into the city, defenders and civilians lived underground. The repeated ground attacks, shelling, and air strikes destroyed most of the city’s buildings, and the city’s streets were strewn with mounds of garbage, rubble, shattered trees, and dead animals.

The human toll was dreadful. An Loc’s streets were littered with the dead, both military and civilian. Soon, diseases such as cholera were running rampant through the ranks of civilians and defenders alike. To avoid a spreading epidemic, ARVN soldiers used bulldozers during the infrequent lulls in the fighting to bury the bodies in mass graves, some of which contained 300 to 500 corpses. Antiaircraft fire had become so intense that it became almost impossible to resupply the defenders by air. With medical supplies exhausted, little could be done for the increasing numbers of casualties. The city’s condition, coupled with the continuous artillery bombardment, demoralized ARVN defenders. The garrison, now numbering about 4,500 troops after the arrival of the two airborne battalions, grimly prepared for the next NVA onslaught.

Once again, the Communists changed plans. The 9th Division commander had been severely reprimanded for his failure to take An Loc after two attempts, and the mission was turned over to the commander of the 5th Division, which would conduct the next main assault. At 5 am on May 11, the NVA opened up with yet another massive artillery barrage. For 12 hours some 8,300 rounds of enemy fire struck the ARVN defensive perimeter, which shrank to a mere 1,000 square yards before the day was over. Meanwhile, seven NVA regiments attacked from the north and northwest supported by tanks. Taking heavy losses, the attackers managed to drive two salients into the ARVN lines, almost bisecting the defensive perimeter. During heavy fighting, the defenders came close to breaking on several occasions, but continued tactical air support kept the NVA units from overrunning the defenders.

AC-130 gunships, Cobra helicopters, and B-52s vied for position in the crowded skies over An Loc to unload their ordnance on NVA forces. Some 297 tactical air support sorties were flown on May 11 alone, followed over the next four days by approximately 260 sorties each day. This air support, flown in the face of some of the most severe antiaircraft fire of the war, broke the back of the Communist offensive, enabling ARVN defenders to stabilize their lines and reduce both enemy salients.

The fighting along Highway 13 involving the ARVN 21st Division did not go as well. The division fought up the highway foot by foot, sustaining heavy casualties in the process, but the ill-coordinated attacks failed to dislodge entrenched NVA defenders along the road. Although it was unable to open the road and link up with An Loc’s defenders, the 21st Division’s efforts were not a total loss. The 21st tied down most of one Communist division, making it unavailable for the fight in An Loc. The presence of one more NVA division in the attack might well have tipped the scales in the Communists’ favor.

Although the fighting was not yet over, by the end of May the tide had turned in the favor of An Loc’s defenders. Around-the-clock air strikes inflicted a terrible toll on NVA formations; the Communists sustained 10,000 casualties in the months of April and May alone. In early June, with the exhausted enemy unable to mount another attack upon An Loc, Minh sent reinforcements into the city and withdrew the battered 5th ARVN Division. Thieu declared the siege broken on June 18. Continuous NVA shelling during the two-month siege had reduced An Loc to total ruins. The ARVN had suffered 5,400 casualties, but with the help of U.S. tactical air power the defenders had defeated three of the finest divisions in the North Vietnamese Army and held the city against overwhelming odds.

As the fighting raged in An Loc, the North Vietnamese attempted to break another stalemate that had developed on the far northern front, pressing their attack southward down Highway 1, across the Thach Han River and on toward Hue City. Fortunately for the South Vietnamese, ARVN and marine divisions had been reinforced by the 2nd and 3rd Brigades of the Airborne Division and the reorganized 1st Ranger Group, raising the ARVN manpower in Military Region I to 35,000 troops. A one-week clearing of the weather allowed the application of massive U.S. bombing.

The North Vietnamese advance was finally halted on May 5. By mid-May, Truong felt strong enough to go on the offensive in a series of limited attacks to throw the Communists off balance, enlarge the defensive perimeter around Hue, and deny the enemy time to maneuver. Between May 15 and 20, ARVN forces recaptured Firebases Bastogne and Checkmate. The NVA launched another attempt to take Hue City on May 21, losing 18 tanks and 800 men in the process. On May 25, a second NVA assault managed to cross the river, but ARVN defenders put up ferocious resistance, forcing the enemy back across the river on May 29. This would prove to be the last serious assault on the defenses of Hue.

By mid-June, clearing weather allowed more accurate aerial bombardment and shelling from U.S. warships offshore. In June, Truong launched Operation Lam Son 72. The 1st ARVN Division pushed westward toward Laos while the Airborne and marine divisions, the 1st Ranger Group, and the 7th Armored Cavalry moved north to retake Quang Tri City. The Airborne Division led the way, utilizing airmobile end-runs to lever the North Vietnamese out of their defensive positions. Within 10 days, ARVN forces had reached the outskirts of the provincial capital. Truong planned to bypass Quang Tri City, isolating the Communist defenders, and push on to the Cua Viet River. Thieu intervened, however, demanding that Quang Tri be taken immediately, seeing the city as a symbol of his authority.

It was not an easy task. The ARVN advance soon bogged down in the outskirts of the city, while the NVA 304th and 208th Divisions were moved to the west to avoid the U.S. firepower. The defense of the city and its walled citadel was left to NVA replacements and raw militia units. Recalled one participant: “The new recruits came in at dusk. They were dead by dawn.”

On July 11, the ARVN Marine Division launched a helicopter assault north and east of the city to cut the last remaining road and force the NVA to reinforce and resupply across the Thach Han River, making them vulnerable to air strikes. During the month of July, American aircraft flew more than 5,000 sorties and 2,000 B-52 strikes to support the counteroffensive. On July 27, the ARVN marines relieved the airborne units as the lead elements in the fighting, but progress continued to be slow throughout the summer. The fighting degenerated into an ugly battle of attrition, vicious house-to-house fighting and incessant artillery barrages by both sides. The heavily defended citadel was finally taken on September16.

The North Vietnamese paid dearly for the ground they gained during the Easter Offensive—approximately 40,000 soldiers killed and another 60,000 wounded. They also lost almost their entire inventory of armor: 134 T-54s, 56 PT-76s, and 60 T-34s. In return, the North gained permanent control of large areas of the four northernmost provinces—Quang Tri, Thua Thien, Quang Nam, and Quang Tin—as well as the western fringes of the II and III Corps sectors, around 10 percent of South Vietnam.

Hanoi wasted no time in making use of what it had gained. The North Vietnamese immediately began to extend their supply corridors from Laos and Cambodia into South Vietnam, as well as rapidly expanding port facilities at the captured town of Dong Ha. Within a year, over 20 per cent of the materiel destined for the southern battlefield was flowing across the docks of Dong Ha.

Peace negotiations resumed in Paris with both sides now willing to make concessions. The last American combat units would leave South Vietnam by the end of March 1973. The fatal weakness of the accords was that NVA troops were allowed to remain in their present positions in South Vietnam, most of which had been taken in the Easter Offensive. It was a virtual death sentence for the South. In early 1975, 20 NVA divisions rumbled south in an offensive that was almost identical to the Easter Offensive and rapidly overwhelmed ARVN resistance. Victorious NVA troops and tanks entered Saigon on April 30. The war was over; the Communists had won.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments