By William E. Welsh

For nearly half a millennium the crossbow and longbow served as the predominant missile weapons for field armies in Western Europe. As such, they would be responsible not only for the death of thousands of common men, but also for the death and wounding of some of the most familiar battlefield commanders of medieval history.

On October 14, 1066, Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwineson was wounded in the eye during the final phase of the Battle of Hastings by an arrow shot high into the air by a Norman archer. Shortly thereafter, he was finished off by Norman cavalry.

During the first week of April 1196, English King Richard the Lionheart was scouting the walls of Châlus-Chabrol Castle in the Limousin region of France when he was struck in the shoulder by a bolt fired by a defender atop the castle walls. The wound subsequently became infected, and the king died before the end of the week.

On March 29, 1461, the Earl of Clifford, who was directing Lancastrian forces in a skirmish that preceded the Battle of Towton in Yorkshire, England, removed his gorget to make himself more comfortable and was immediately struck by an arrow fired by a Yorkist longbowman.

Some monarchs were luckier. French King Philip VI was struck in the face by an arrow at the Battle of Crécy on August 26, 1346. Also in that year, Scottish King David II was struck by two arrows at the Battle of Neville’s Cross on October 17. Prince Hal, who would become English King Henry V, was struck just below the eye by an arrow during the Battle of Shrewsbury on July 21, 1403. English King Henry VI was hit in the neck by an arrow at the First Battle of St. Albans on May 22, 1455. Fortunately for these individuals, those wounds would not prove fatal.

The lethal threat that the crossbow posed to knights, nobles, and kings on the battlefield was the very reason that Pope Innocent II issued a papal bull in 1139 condemning the use of the crossbow. The crossbow was more widespread than the longbow at the time the bull was issued. The crossbow undermined the feudal system that served as the foundation for Western Christendom. A peasant could be shown how to use a crossbow rather quickly, and in his hands the weapon potentially could kill anyone on the battlefield, whether or not they wore armor. Knights regarded crossbows as unchivalrous weapons. Despite this, medieval commanders desired this killing power in their ranks, and the ban was universally ignored.

English and French armies relied heavily on archers to defend castles, peel towers, and walled cities. Bowmen defended these places from protected positions on battlements and through loops in walls and towers.

From the 11th to the 14th centuries, the English and the French recruited both types of bowmen for their field armies. However, in the 14th and 15th centuries the English primarily used longbowmen in their field armies, whereas the French continued using crossbow mercenaries.

English field armies in the 14th century became nearly invincible by massing longbows in large numbers. Able to fire as many as a dozen arrows in a minute, longbowmen trained from a young age to use their self-tailored weapon with proficiency, and working in unison, were able to put hundreds, and in large battles thousands, of arrows in the air. The flocks of arrows made a loud whooshing sound and darkened the sky on their short but deadly flight. Besides the tangible danger of killing or maiming that they posed, the concerted effect of these storms of arrows struck terror into enemy forces. When longbows were used to deliver a flanking fire against an enemy formation, additional deaths were caused by suffocation and trampling as those targeted sought to escape the incoming arrows.

In ancient times small crossbows were used by the Greeks and Romans in Europe. During the Middle Ages, the crossbow underwent a range of mechanical improvements. These improvements made it possible to load while standing and also boosted the velocity of the missile, known as a bolt or quarrel. Certain regions where the crossbow was used heavily, such as Gascony and Genoa, developed a reputation for having skilled crossbowmen. For this reason, the crossbowmen from these regions were hired as mercenaries by nobles from other areas.

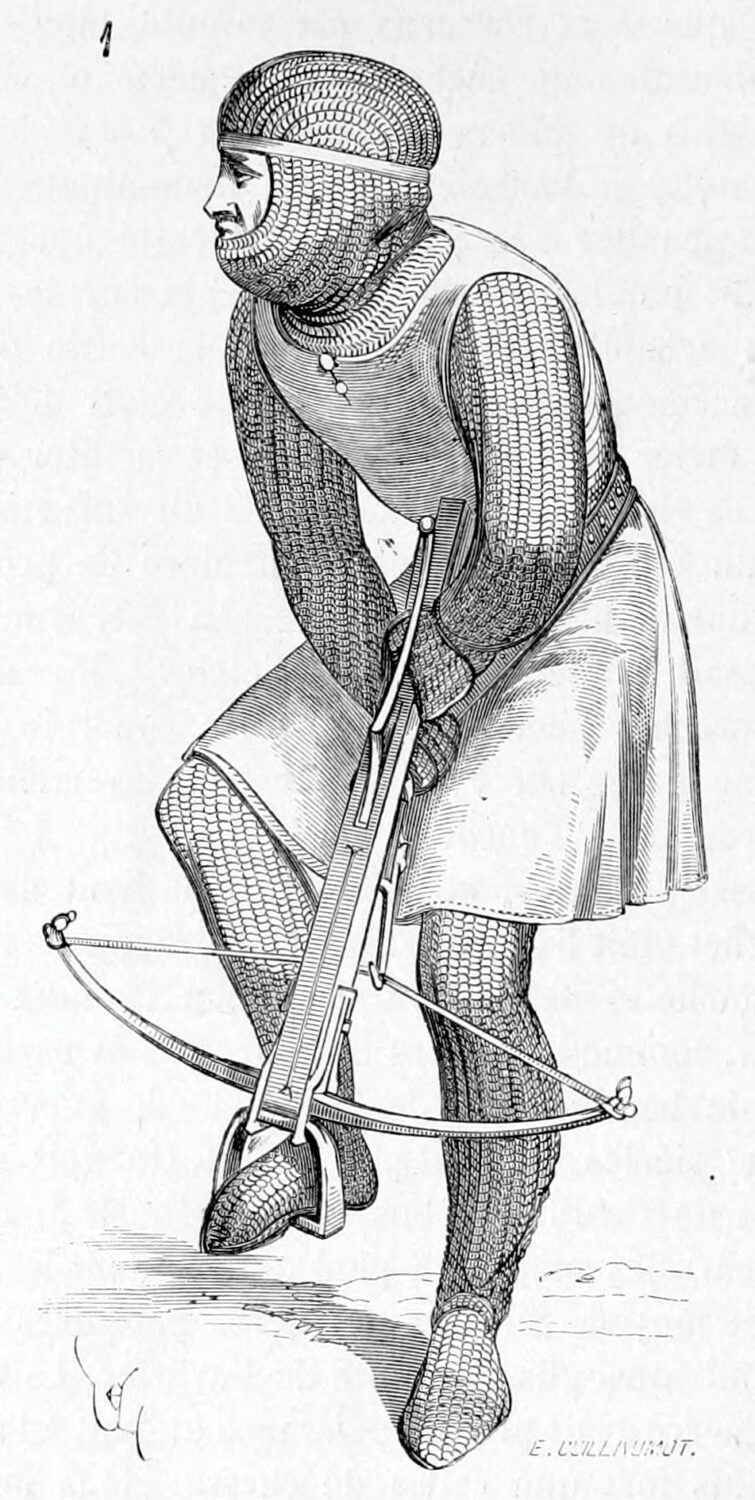

The crossbow consisted of a small bow generally measuring about 24 inches long that was mounted horizontally on a wooden stock (known as the tiller) about 30 inches long. The stock had grooves for the bolt and handle and sights for aiming.

The fletching for the 12-inch bolts was not made of feathers like regular arrows, but instead of leather or other sturdy materials. To load his weapon, the crossbowman placed a bolt—with a four-sided square point that enabled it to penetrate armor—in the shallow groove atop the stock. He fired the weapon by pulling a trigger underneath the stock.

A crossbowman prepared his weapon to fire, a process known as spanning, either by putting his foot in one stirrup or both feet in two stirrups and drawing the string with his hands. Smaller crossbows could be loaded using a hook attached to a wide belt, which enabled the crossbowman to stay upright.

Byzantine princess Anna Comnena described in her 12th-century writings the difficult task of loading the kind of crossbow that was used in the Crusades.

“[The crossbow] has to be loaded lying almost on one’s back; each foot is pressed forcibly against the half circles of the bow and the two hands tug at the bow, pulling with all one’s strength towards the body,” wrote Comnena.

The draw weight of the crossbows used in the Crusades was about 150 pounds. The crossbow had a range of about 200 yards, which increased to as much as 400 yards by the 15th century as a result of technical advances in its design, such as the use of a windlass to span the weapon.

Comnena’s lengthy description of the 12th-century crossbow testifies to its killing power. Crossbow bolts had enough force to “transfix a shield, cut through a heavy iron breastplate and resume their flight on the far side,” wrote Comnena. “An arrow of this type has been known to make its way right through a bronze statue, and when shot at the wall of a very great town its point either protruded from the other side or buried itself in the wall and disappeared altogether.”

In addition to the short training period required to operate a crossbow, another key advantage was that it could be loaded and carried around by the soldier until ready to be fired.

The primary disadvantage to the crossbow was its slow rate of fire. While not as important in siege warfare, this shortcoming became a glaring weakness in field combat. The typical rate of fire for a crossbow was two times a minute. Highly professional crossbowmen using the belt and hook method were able to double that rate of fire. The slow rate of fire became problematic when crossbowmen fought against longbowmen or horse archers armed with a composite bow.

A crossbowman needed some form of protection in open warfare while he was loading his weapon. For this reason, a crossbowman typically carried a large convex shield, known as a pavise, with a spike in the bottom. He planted the pavise in front of him to give him some measure of protection.

When Duke William of Normandy began assembling an army to invade England in 1066, he recruited both crossbowmen and bowmen using self bows (a slightly shorter version of what would become the longbow) from his duchy. He also hired mercenaries proficient in the use of the crossbow.

Archers were the first troops to go ashore when the Norman vessels arrived at Pevensey in Sussex on September 28. They secured the landing for the knights to bring ashore their horses. The archers “were ready to attack, ready to flee, ready to turn about and ready to skirmish,” wrote Norman chronicler Master Wace.

On October 14, the day of battle, William organized his army into three ranks with his archers in the first rank. Their job was to shower arrows and bolts on the tightly packed ranks of English King Harold’s army, which stood behind its shields atop Senlac Hill. William hoped that the hail of missiles would disrupt the enemy ranks so that the Norman cavalry would be able to shatter their cohesion and drive them from the battlefield with heavy losses.

Although the initial fire of William’s archers failed to produce the desired result, it was after the feigned flight of the Norman cavalry that the missile fire began to have a telling effect on the English. The Normans showed a tactical flexibility that the English did not possess. Furthermore, the English did not have comparable missile troops with which to inflict casualties at a distance on the Normans.

In the initial stages of the battle, the archers fired at a high trajectory to produce wounds to the head and arms of their foe. But during the final stages of the battle, the Norman archers alternated between showers of arrows and firing directly at the English infantry. The powerful crossbow bolts easily pierced the English infantry’s shields. “The bands of archers attacked and from a distance transfixed bodies with their shafts and the crossbowmen destroyed the shields as if by a hailstorm, shattered them by countless blows,” wrote Bishop Guy of Amiens.

A shower of arrows and bolts rained down on King Harold and his bodyguards, wounding Harold in the eye. By that time, the Norman cavalry had penetrated the English ranks, and Harold was killed.

In the First Crusade, which began in 1096, Frankish armies employed crossbow formations in their vanguards to keep Turkish horse archers away from their columns on the march. Similarly, they also used crossbowmen as skirmishers when battle became inevitable. The Frankish crossbowmen engaged the Turkish horse archers while the Frankish heavy cavalry deployed for battle.

William the Conqueror introduced the crossbow to England, and during the next two centuries English monarchs actively recruited crossbowmen to defend the country’s northern border with Scotland and to protect Angevin territories on the Continent from encroachments by the Capetian dynasty.

English King Richard III, the principal commander of Christian forces in the Third Crusade, relied heavily on mercenary crossbowmen to protect his mounted knights. At the Battle of Jaffa on August 4, 1192, Richard ordered his spearman and crossbowmen to form a circle to protect his knights. He alternated a pair of crossbowmen between each spearman. The pairs of crossbowmen worked together: one fired while the other loaded. Inside the circle were Richard and a small group of knights. When the Turkish cavalry approached, they were met with deadly fire from the crossbows. Once the Turkish light cavalry had been sufficiently weakened, Richard and his knights sallied forth through a gap and drove them off.

Richard the Lionheart, as well as his successors King John and King Henry III, employed both types of archers in the armies they fielded in England and France during their respective reigns.

In the Second Battle of Lincoln, which was fought on May 20, 1217, during the First Barons’ War, crossbows played a decisive role. William Marshal, First Earl of Pembroke, who was serving as the regent for 10-year-old Henry III, placed the crossbowmen in the vanguard of an army that marched to raise the siege of the town of Lincoln. Led by Sir Falkes de Breauté, the crossbowmen captured the town’s north gate. They then spread out onto the rooftops of the town and began firing on the army of the rebellious barons. After the rebel army had become disordered, Pembroke smashed it with a mixed force of infantry and cavalry.

The Capetian monarchs also used crossbowmen as a screening force for the main body of their armies. On his march through Flanders in the days leading up to the Battle of Bouvines fought July 27, 1214, Philip II established a formidable rear guard that included crossbowmen to prevent his army from being overtaken unexpectedly by Emperor Otto IV’s imperial army. Similarly, Philip III in 1285 protected his army when it entered Catalonia during the Aragonese Crusade by deploying crossbowmen as skirmishers in front of his army and on its flanks.

The armies of England and France also employed archers using the self bow, which was individually constructed to suit each bowman. This was a continuation of the use of the self bow by the Franks and the Vikings in earlier centuries. Crews of Viking longships used the self bow not only in sea battles but also to cover shore landings. Self bows before the 14th century ranged in length from five to six feet, but by the 14th century the longbows used by the English in the Hundred Years War averaged six feet in length. The term longbow was not used at the time. It was introduced in the mid-15th century and was used widely by historians beginning in the 19th century.

The longbow was made from a single long, thin piece of wood, the length of which was tailored to the archer’s height. A number of woods were well suited for the construction of a longbow, including yew, ash, elm, and hazel. The rounded stave was crafted so that the springy sapwood went on the outside, away from the archer, with the sturdier hardwood on the inside facing the archer. This design gave the stave the snap necessary to propel an arrow toward its objective.

Once the bowyer had carved the stave, it was bent into a D-section. The narrow tips of the stave where the bowstring was looped were called nocks and fashioned from horn. The bowstring was typically made of hemp or flax and coated with glue to protect it from moisture.

The longbow had a maximum range of 300 yards but was most effective at 200 yards. Importantly, the longbow was capable of penetrating plate armor only at close range. The longbowman fired his weapon by turning to his side, pushing the stave away from his body, and drawing the bowstring to his ear. The key advantage of a longbow over a crossbow was its superior rate of fire. A skilled longbowman could fire as many as 12 arrows per minute.

Longbow arrows were typically 27 inches long. When outfitted with a five-inch iron bodkin, they were 32 inches in total. The handcrafted arrows were made of ash, birch, and as many as a dozen other woods. The ideal fletching for the arrows came from either the feathers of the gray goose, swan, or peacock. Three feathers were glued or bound to the arrow to stabilize it during its flight. Arrows were issued to archers in bundles, known as sheaves, of 24. The sheaves came in drawstring bags made of soft cloth that were suitable for use as quivers.

In a major transformation in battlefield tactics, the English transitioned in the 14th century to using only longbows in their field armies. To ensure that the longbows were well supported by other parts of the army, Edward III issued a proclamation in 1327 during the Weardale campaign against the Scots informing all nobles and yeoman that they should be prepared to fight dismounted in battle.

On the battlefield, longbowmen always operated from protected positions where they would not be vulnerable to enemy cavalry. They used a variety of natural features for protection, such as hedges and marshes. If these features were not available or if they felt the need to supplement them, they built mounds, dug pits or trenches, or planted sharpened stakes angled toward their foe.

Some of the battlefield tactics involving archers that would become routine for English armies in the wars they waged with longbows against the Scottish and the French were first introduced during the Anglo-Norman battles fought in the 12th century.

The Battle of Standard fought August 22, 1138, in which an English army led by Archbishop Thurstan of York defeated a Scottish army led by King David I, was a victory achieved almost entirely by English archers. While English King Stephen was tied down fighting rebellious barons in southern England, Thurstan assembled an army of troops drawn from the shires of northern England to combat the invading Scots.

The Galwegians, a volatile component of King David’s army, insisted on leading the attack against the English. The English battle line, which consisted of men-at-arms interspersed with archers, withstood the ferocious charge of the Galwegians, who because of their complete lack of armor were highly vulnerable to the hail of arrows that met them as they closed with the English.

“Like a hedgehog with its quills, so you would see a Galwegian bristling all around with arrows, and nonetheless brandishing his sword and in blind madness rushing forward to now smite a foe, now lash the air with useless strokes,” wrote Abbot Ailred of Rievaulx.

Other Scottish troops who followed in the attack also were repulsed by the archers, and a mounted charge led by Earl Henry, the king’s son, was unable to disrupt the tight cohesion of the dismounted English army.

What was significant about the Anglo-Norman battles of the 12th century that eventually would become cornerstones of English longbow tactics was the devastating defensive power of archers when placed on the flanks and the ability of dismounted men-at-arms and archers to withstand a charge by heavy cavalry.

The army that Edward I fielded to combat the Scots in the First War of Scottish Independence contained both types of archers. While Edward likely increased the number of longbowmen in his ranks from his experience conquering Wales between 1277 and 1283, he still employed large numbers of Gascon crossbowmen in his army.

In 1298, Edward I, also called Longshanks, marched north to avenge the English loss to the Scots at Stirling Bridge the year before. He had present for battle on July 22 at Falkirk approximately 16,000 infantry and 2,500 cavalry. Approximately three quarters of the English infantry were archers, including a large number of longbowmen recruited from Wales and the heavily forested areas near that region, such as Cheshire and Lancashire. The initial English attack consisted of a mounted charge. While it failed to crack the Scottish schiltrons, it drove off 200 Scottish knights stationed nearby. The Scottish archers, who were deployed outside the spear formations, were subsequently slaughtered by the English cavalry.

Edward then ordered his archers to fire steady volleys of arrows at the Scottish schiltrons. Once the schiltrons had suffered heavy casualties, Edward ordered his knights to launch a second attack. The English knights took advantage of the large gaps in the Scottish schiltrons to ride into them and carve them up. The Scots lost the battle and half their army in the process.

Longshanks’ son, Edward II, was not a good general. At Bannockburn, fought June 24, 1314, Edward II failed to deploy his archers properly. They formed part of the second rank of troops and marched into battle behind the mounted knights. After the English cavalry failed to break the schiltrons, Scottish King Robert the Bruce ordered a mounted flank attack against the archers. Without any protection, they were cut to pieces.

The tactical lesson of the First War of Scottish Independence, during which Falkirk and Bannockburn were fought, was that unprotected archers could not withstand a cavalry attack alone. Since the English had far greater reserves of archers than the Scots, it certainly behooved them to find a way to protect the valuable missile troops in future battles. The job would fall to Longshanks’ grandson, Edward III, as well as his lieutenants and allies.

In the summer of 1332, a group of Scottish and English lords who were the heirs of nobles who had been opposed to King Robert the Bruce and had lost their lands as a result, invaded Scotland seeking to depose its king. Known as “the disinherited,” the lords, who were led by Edward Balliol, had secured English King Edward III’s approval for their mission. Balliol’s small force of 1,500 men was attacked on August 12 by Bruce’s much larger force in what became known as the Battle of Dupplin Moor. Heeding the advice of Henry de Beaumont, a veteran of Falkirk and Bannockburn, Balliol quickly ordered his men-at-arms to dismount and form a line of battle. The archers were placed on each flank at a 45 degree angle.

The English men-at-arms initially were driven back, but they counterattacked and regained the ground they had lost. While the melee was raging, the English archers fired rapidly into the flanks of successive waves of attacking Scots. In an effort to avoid the fire, the Scots on the outside moved toward the center of the formation. The result was that many Scots fell down and were trampled to death. Just as bad, those who remained standing were unable to wield their weapons properly. “There was disaster so cruel that whoever in that great throng fell never had the chance to rise again,” wrote the Scottish Andrew Wyntoun. The battle ended in a decisive victory for “the disinherited.” Of the 500 English men-at-arms engaged, only 30 were killed; the Scots lost more than 2,000 men.

Twenty-one-year-old Edward III invaded Scotland in 1333 to assist Balliol in overthrowing David II, Bruce’s heir. Edward arrived in May to take charge of the siege of Berwick upon Tweed, which had begun earlier that year under Ballioll’s direction. Sir Archibald Douglas, the regent for the nine-year-old Scottish king, arrived on July 19 with a substantially larger force than Edward’s to relieve the garrison. Edward shifted his army north to a strong position atop nearby Halidon Hill. Edward placed archers on the wings of each of his three dismounted divisions and awaited the onslaught.

The difficulty the Scots had in traversing marshy ground at the base of the hill played a role in breaking up their cohesion and in the piecemeal fashion in which they hurled themselves at the English. The battle began when the Scottish division of Thomas, First Earl of Moray, charged uphill toward Balliol’s division deployed on the left flank of Edward’s army. Moray’s men were driven off with heavy losses. “The Scots marching in the first division were so grievously wounded in the face and blinded by the host of English archery … that they were helpless, and quickly began to turn their faces from the arrow flights and to fall,” according to the Lanercost Chronicle.

All along the English line the Scottish attack was repulsed primarily by the well-directed, uninterrupted volleys of Edward’s skilled longbowmen. Only on the English right flank did the fighting become a close thing when Douglas’s best warriors tried to break through to relieve the garrison at Berwick. Of the 14,000 Scots, 4,000 lost their lives in the slaughter. Douglas was among the Scottish roll call of dead.

Halidon Hill marked the beginning of a long string of English victories on the battlefield that can be directly attributed to the formula in which men-at-arms fought dismounted to support large formations of longbowmen whose volleys were able to shatter mounted and dismounted attacks alike.

Not all victories against the Scots would be as easily won as those of Dupplin Moor and Halidon Hill, though. Following Edward III’s victory against the French at the Battle of Crécy in the summer of 1346, French King Philip VI asked his ally, King David II, who was in exile in France at the time, to relieve military pressure on the French by launching an attack on northern England.

Two months after Crécy, the Scottish king returned to his homeland to fulfill the request. A hodgepodge force of English under the command of magnates Ralph Neville and Henry Percy marched to intercept the Scots in Durham in what became the Battle of Neville’s Cross. The French had furnished David with substantial funds, which he used to buy expensive armor. In the front rank of Scottish armor were men-at-arms wearing the best armor of the day. When the English longbowmen fired at the Scots, their arrows glanced off the warriors wearing the new armor.

As at Halidon Hill, the archers at Neville’s Cross, fought October 17, 1346, were deployed in support of each division. Although the archers attached to the division led by Thomas Rokeby, sheriff of Yorkshire, on the English left repulsed the Scots easily, the Scots attacking the center and right divisions of the English army enjoyed initial success against their English foes. “With heads inclined and covered with iron, with polished helmets and tightly fastened shields, [the Scotsmen] frustrated the arrows of the English at the beginning of the battle,” wrote chronicler Geoffrey le Baker.

Morale was particularly high in the Scottish center, which David led forward to the attack. The English archers belonging to the center and right divisions fled to the rear for safety, leaving the men-at-arms in full harness to beat back the spirited Scottish attack. “Twice our archers and common soldiers retreated, but our men-at-arms stood firm and fought stubbornly until the archers and the foot-soldiers rallied,” wrote participant Thomas Samson.

By committing a small mounted reserve in the late stages of the battle, the English were able to drive off both the left and right divisions of the Scottish army, leaving the king’s division in the center assailed from three sides. The Scottish king, who had been struck by two arrows, was captured. He was subsequently imprisoned for more than a decade in the Tower of London.

Edward III and his lieutenants employed their new tactics centered on the longbow in the first phase of the Hundred Years War, which lasted from 1337 to 1360.

A showdown between rivals Edward III and Philip VI occurred on July 12, 1346, when Edward landed with an army of approximately 15,000 men—11,000 of which were archers and 4,000 of which were men-at-arms—on the Cherbourg peninsula in Normandy. The English began a chevauchée moving east across northern France. Six weeks later, Edward took up a position near the village of Crécy in Flanders to offer battle to Philip’s French army, which had been pursuing them. Philip’s army had been tracking Edward’s army for some time, and when pressure from the French nobility to stop the English pillaging mounted in mid-August, Philip decided to overtake the invaders.

When the English deployed on a ridge north of Crécy on August 25, Edward had his troops dig a series of camouflaged pits, each of which was a foot deep and a foot wide, to hinder a charge by French cavalry directed at his men-at-arms in the center and archers on the flanks.

The archers “were positioned at the sides of the king’s army almost like wings; in this way, they did not hinder the men-at-arms, nor did they meet the enemy head on, but could catch them in their cross volleys,” wrote chronicler Jean le Bel.

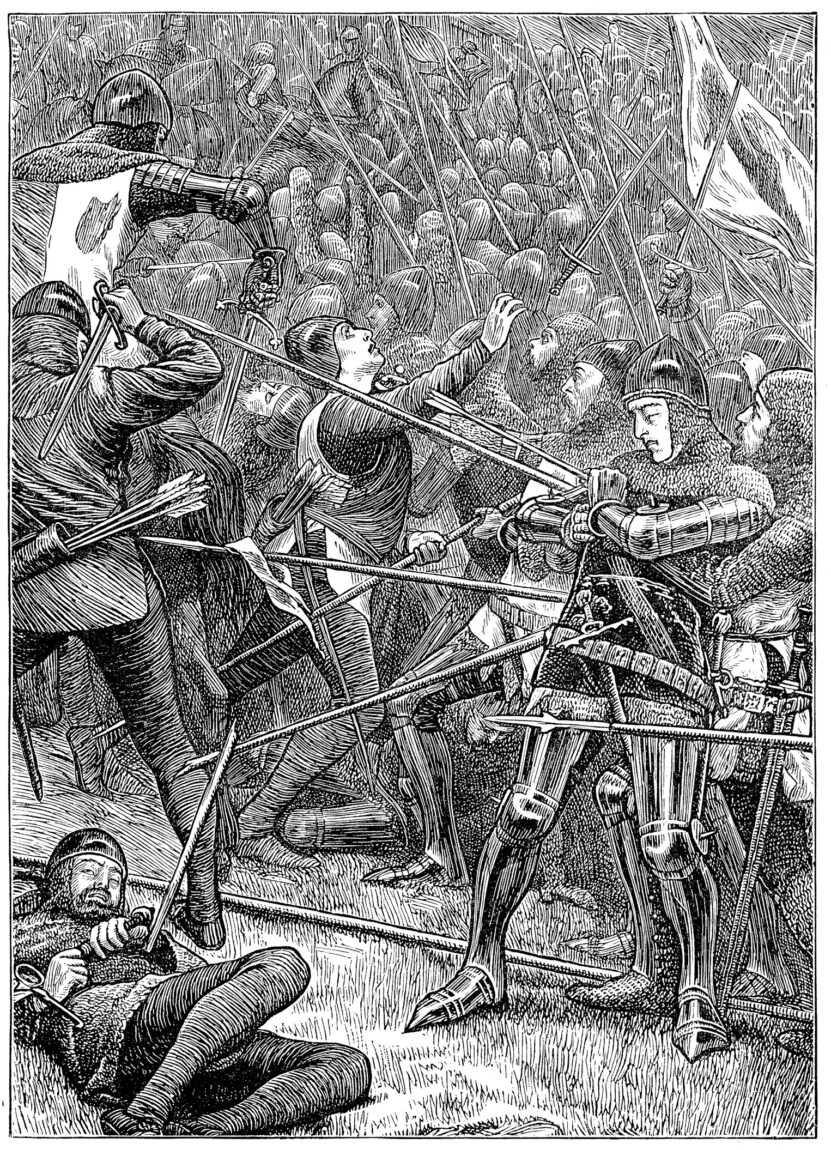

The following day, the French arrived in force. Philip, whose army was twice as large as Edward’s, ordered his troops to attack at once, even though portions of his army were still on roads leading to the battlefield. The decision was disastrous for the 2,000 Genoese crossbowmen, whose pavises were still on baggage carts at the rear of the army.

The Genoese advanced first in an attempt to soften the English for a mounted attack to follow. Their bolts fell short of the English line, while the English bowmen fired their arrows in a high trajectory that reached the Genoese troops. Suffering crippling and fatal wounds to the face, chest, and arms, the Genoese fell back.

Enraged at the inability of their mercenaries to inflict any casualties on the English, the French nobles rode over the Genoese as the knights began the first of a series of mounted charges against the English position. The French made as many as 15 separate attacks, each of which was broken up by the arrows fired rapidly by the longbowmen on the flanks.

“That day the English archers gave tremendous advantage to their side,” wrote the chronicler Froissart. “Many say it was by their shooting that the day was won.”

Edward, Prince of Wales, known as the Black Prince, who was Edward III’s son, had as much success as his father did at Crécy when he faced the full might of the French royal army at Poitiers, fought September 19, 1356. French King John II came to power in 1350, and six years later he sought to destroy the Black Prince’s army, which was operating from Aquitaine. The Black Prince launched a devastating chevauchée in 1355 through the Languedoc region, and the following year he led another chevauchée into the Poitou region.

The French royal army of 20,000 outnumbered Prince Edward’s army by more than three to one. Accompanying King John was Sir William Douglas, who advised the French king on tactics based on his experience fighting the English. Knowing that the English longbow had decimated French cavalry attacks, John resolved that the bulk of his army would fight dismounted. The Black Prince was in the process of withdrawing his army south when he was forced to turn around and give battle or lose a portion of his army before it could reach the safety of the forest.

Despite having to move his men from column to line unexpectedly, the Black Prince still enjoyed all of the advantages the terrain had to offer. A ridge, which was protected by a hedgerow, ran nearly the length of the English position. Edward entrusted the division on his right flank, the most exposed part of his position, to the Earls of Salisbury and Suffolk, and the division on his left flank to the Earls of Oxford and Warwick. The English left flank, which was positioned behind a marsh, was the strongest part of Edward’s line. The Black Prince commanded the center division.

John allowed two of his marshals to lead a mounted attack consisting of 250 knights against each wing of his foe in an attempt to wipe out the English archers. The longbowmen on the English right flank slaughtered the French heavy cavalry as it tried to charge through a gap in the hedgerow. Meanwhile, the French cavalry attack against the English left flank stalled in front of the marsh. Seeing that the French horsemen were within range of his longbowmen, Oxford ordered them to walk through the marsh to a place where they could fire into the unprotected flanks of the horses. Oxford’s archers sent multiple volleys of arrows at the horses. Because of this, “the wounded chargers reared, or turned back on their own men” as the next wave of attack already was underway, wrote le Baker.

When the English observed a large formation of crossbowmen advancing against them, Warwick ordered a contingent of his knights to mount their horses. The small-scale English cavalry sortie overran the unprotected crossbowmen and eliminated them from the fight.

John had arranged his men-at-arms and infantry in three divisions. The first was led by his son, the dauphin, the second by the Duke of Orleans, and the third by himself. The English archers sent hails of arrows streaming down from the sky on the dauphin’s division, playing a large part in breaking up the force of its attack once it reached the hedgerow.

Seeing the lack of success by the dauphin’s division, the Duke of Orleans unexpectedly broke off his advance and led his division from the field. However, John led his division, which included a group of crossbowmen, against the English line. By this time, the English archers had run out of arrows and were forced to pick up spent arrows from the ground and even pull them out of the bodies of “wretches who were only half dead,” wrote the chronicler Chandos Herald.

The battle ended in an English victory and the capture of the French king when Jean de Grailly, Captal de Bush, who was a French ally of the Black Prince, led 60 mounted men-at-arms and 100 mounted Gascon crossbowmen in an attack against the left flank of John’s division. By that time, the English longbowmen had cast aside their bows and joined the melee using their daggers and swords.

Following the decisive English victory at Poitiers, Edward III sought to protect English dominance with the longbow by issuing a proclamation banning the export of longbows and arrows in 1357, which he followed in 1365 with a law forbidding archers to leave England without royal permission.

When Edward III learned that his people had become complacent about their longbow skills and were no longer practicing regularly on Sundays as they had previously, he instructed England’s sheriffs in 1363 to enforce archery practice by both nobles and commoners. “The art [of archery] is almost totally neglected and the people amuse themselves with dishonest games so that the kingdom, in short, has become truly destitute of archers,” Edward told the sheriffs.

English tactics for deploying the longbow continued to evolve in the third and final phase of the Lancastrian period of the Hundred Years War that began in 1415. Longbow archers, which were less expensive to equip than men-at-arms, would become increasingly important to operations in English-held areas on the Continent, such as Normandy and Aquitaine. During Henry V’s campaign in 1415, the ratio of archers to men-at-arms increased to five to one, and in the final decades of the conflict the ratio would soar to nearly 10 to one.

As typical of all of the large battles between the English and French during the Hundred Years War, the French royal army led by Charles of Albret, Constable of France, against Henry V in 1415 was four times larger than Henry’s army of 6,000 men. To protect his archers from French mounted attacks designed to overrun them, the 29-year-old English king ordered his bowmen to cut six-foot-long stakes to plant at an angle in front of them to guard against cavalry charges. The king further instructed that the stakes were to be planted not in a single line but in a checkerboard fashion so that the archers could move forward or sideways as necessary to get the best angle of fire against enemy attacks.

The 25,000-strong French army, which included not only 1,000 crossbowmen but also 4,000 longbow archers, blocked the English march from Harfleur to Calais near the village of Agincourt in western Artois when the English were just a two-day march from Calais. Heavy rains had turned the ground to muddy soup.

On October 25, the two armies faced off, each waiting for the other to attack. To force the French to attack, Henry made the risky decision to have the English army advance a few hundred yards to entice the French to charge. This meant the archers had to pull up their stakes, march

forward with them, and replant them. Unfortunately for the French, Albret failed to order an immediate cavalry assault when the English archers were at their most vulnerable trudging through the muck carrying their stakes.

Once the English had reset themselves for the French attack, Henry ordered the archers on the flanks to commence fire as they were now within bowshot of the enemy. A shower of arrows produced the desired result, and French cavalry thundered forward on the flanks in an effort to overrun the English archers.

The French flanking cavalry was “forced to fall back under showers of arrows and to flee to their rearguard,” wrote the anonymous author of the Gesta Henrici Quinti. Some of the wounded horses careened into the first division of French dismounted men-at-arms and infantry, who slogged through the mud toward the English lines. Although Albret had 5,000 archers, they were relegated to the second line of the vanguard, which greatly hampered their ability to fire effectively. The dismounted French men-at-arms only closed with the English line of battle in a few places, in large part because of the devastating accuracy of the English longbow fire. “The English [longbowmen] shot so vigorously that none dared to approach them,” wrote chronicler Jean Le Fevre.

After the first French division had been destroyed, the second French division attempted to move through it and reach the English line. The mud and piles of dead, dying, and wounded Frenchmen made their task extremely difficult. After some desultory fighting, it too was driven off. By then, the English archers had fired all their arrows, and as at Poitiers they joined the English men-at-arms who left their defensive positions to defeat any pockets of French resistance and round up nobles worth ransoming.

Duke John of Bedford, who served as the regent for his young nephew Henry VI, led English forces against a combined Franco-Scottish army in the Battle of Verneuil on August 17, 1424. Bedford not only placed archers on the English flanks but also designated 2,000 mounted archers to guard the baggage train parked behind the English host.

The battle began with the usual French mounted attack against the archers on the flanks. This time the cavalry on the Franco-Scottish left flank scored a noteworthy success against the archers directly under the control of Bedford, who commanded the English right wing. Because of a prolonged summer drought, the ground was hard as rock, and the archers were not able to pound their protective stakes into it. As the French cavalry bore down on them, the archers formed into groups hoping to find safety in numbers. This allowed the French knights to pour through gaps in their position and gallop into the English rear. However, Bedford’s mounted reserve checked the French cavalry’s advance and prevented them from attacking from behind the English men-at-arms in the center of the field.

On the English left, Thomas Montacute, the Fourth Earl of Salisbury, found his troops involved in a much more sanguinary fight against the Scottish troops, whose hatred of the English surpassed that of the French. The Scottish force, led by Archibald Douglas, First Duke of Touraine, included a contingent of longbowmen, which engaged in a grueling duel for supremacy with Salisbury’s archers. “They began to shoot against each other so murderously it was horrible to watch,” wrote chronicler Jean de Waurin.

While the missile fire was impressive, it did little to influence the outcome of the battle. When Bedford vanquished the French, he reinforced Salisbury. Assailed on three sides, the Scottish troops were slaughtered on the battlefield. Bedford won a mighty victory, which allowed the English to retain their grip on Normandy and Ile de France.

The Wars of the Roses, which began in 1455, involved an interesting twist on the use of longbows. Since English armies during the 30-year dynastic struggle fought dismounted, there was no need to place archers on the flanks to disrupt enemy cavalry charges as had been the case in the battles during the Hundred Years War against large French armies. In most cases both Lancastrian and Yorkist armies had groups of archers, and therefore they did not enjoy an advantage over their opponent as had been the case against the French.

When the armies met each other in battle, the archers led the way as skirmishers. When the two sides came within bow range of each other, the archers participated in a “shootout.” In most cases, commanders preferred to be on the tactical defensive. The goal was to disrupt the ranks of the other side with arrow fire to the point that its commanders were provoked into ordering a general advance. A perfect example of this occurred at the Battle of Towton on March 29, 1461.

On the morning of the battle, Richard Neville, the 16th Earl of Warwick, ordered his uncle, William Neville, Lord Fauconberg, to take a group of mounted archers and ford the Aire River three miles upstream, which caught the Lancastrians by surprise. In the ensuing clash, Lancastrian Earl John Clifford was slain when a Yorkist arrow struck him in the throat.

The Lancastrians guarding the river retreated. Led by 18-year-old Edward IV, the Yorkists marched six miles before reaching the main Lancastrian army. Fauconberg ordered his archers to the front, and they shot their arrows toward the enemy. The wind favored the Yorkists, carrying their arrows into the ranks of the enemy, while the wind blowing into the faces of the Lancastrians prevented their volleys from reaching the Yorkists.

Thus Fauconberg provoked the Yorkist commanders, Sir Andrew Trollope and Henry Percy, 3rd Earl of Northumberland, into a premature attack. The fighting was desperate throughout the afternoon until the Yorkist rear guard led by John Mowbray, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, gave the Yorkists sufficient manpower to overwhelm the Lancastrians and break their lines. No quarter was given, and the majority of the Lancastrians participating in the battle perished.

The slow but steady decline of the longbow occurred over the course of the 16th century. The quartermasters of fortifications on the southern coast of Britain and extant English holdings in France, such as Boulogne and Calais, still stocked hundreds of longbows, which were far less expensive than the newly developed arquebus. But weighing in the arquebus’ favor was its ability to more easily penetrate plate armor than a bodkin-tipped arrow, as well as its ease of use.

At the Battle of Flodden, fought September 9, 1513, an army of English infantry comprised of levies from the shires of northern England and armed with longbows and halberds confronted an invasion army twice its size led by Scottish King James IV. In the ensuing battle, the archers had only limited success with their arrows against Scottish troops well protected by chain mail and padded jackets. The English were victorious largely because the halberd proved to be a better weapon for close quarters combat than the Scottish pike. The questionable performance of the longbow at Flodden contributed to its falling into disfavor.

Unlike the longbow, a soldier did not have to practice with the arquebus on a regular basis to become proficient. The wholesale replacement of the longbow with the arquebus began in southern England and gradually spread north. The northern shires were the last to use the longbow before the English government made an official switch to the arquebus in 1595. In that year, Elizabeth I’s Privy Council sounded the death knell of the longbow when it officially declared that the arquebus should replace the bow as the primary weapon of the shire militias.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments