By Robert Heege

It was the first week of April 1941, and Lt. Gen. Richard O’Connor could scarcely believe what was happening as his driver suddenly cocked the wheel and swerved hard left, flooring the gas pedal in a futile attempt to outrun the multiple bursts of machine-gun fire erupting all around them, lighting up the Saharan night as bullets chased after his wheels. A moment later O’Connor’s vehicle had ground to a halt, the unmistakable ping of bullets ricocheting off shattered steel rims still ringing in his ears.

As commander of the British Army’s XIII Corps, he had led men through an impressive string of successes against the Italian arm of the Axis camp. It was there, among the arid, unforgiving wastes of North Africa, that he had helped scotch, once and for all, it seemed, the overreaching hubris of Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini and his puerile dream of turning the Mediterranean into an Italian lake.

As O’Connor sat peering out over the windscreen from the passenger side of his Lend-Lease American-made jeep, his eyes squinting in the ink-black darkness on the outskirts of Martuba, it was his own turn to face his dog day in the desert. Staring into the business ends of the submachine guns pointing directly at him from what passed for a road in the Libyan backwater, he could do little more than slump dejectedly in his seat and put up his hands.

In action almost without interruption since the summer of 1940, O’Connor and his hard-fighting corps had fought to counter Mussolini’s ill-fated invasion of Egypt. Having helped to carry the day almost within the shadow of the pyramids, they had fought on with the rest of the British and Imperial forces, racking up victory after victory over their numerically enormous adversary.

Seizing the initiative, they had continued their counterattack, rolling up the unwieldy Italian forces arrayed against them, not only driving the Italians from the Egyptian frontier, but by February 1941 nearly succeeding in pushing them completely out of the whole of their Libyan colony. Then, with all of eastern Libya and Cyrenaica in British hands and what little remained of the Italian forces in the western rump of the country all but finished off, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill rashly ordered some of the most seasoned units in North Africa, including many of O’Connor’s finest, diverted to the Aegean Theater in support of Greece.

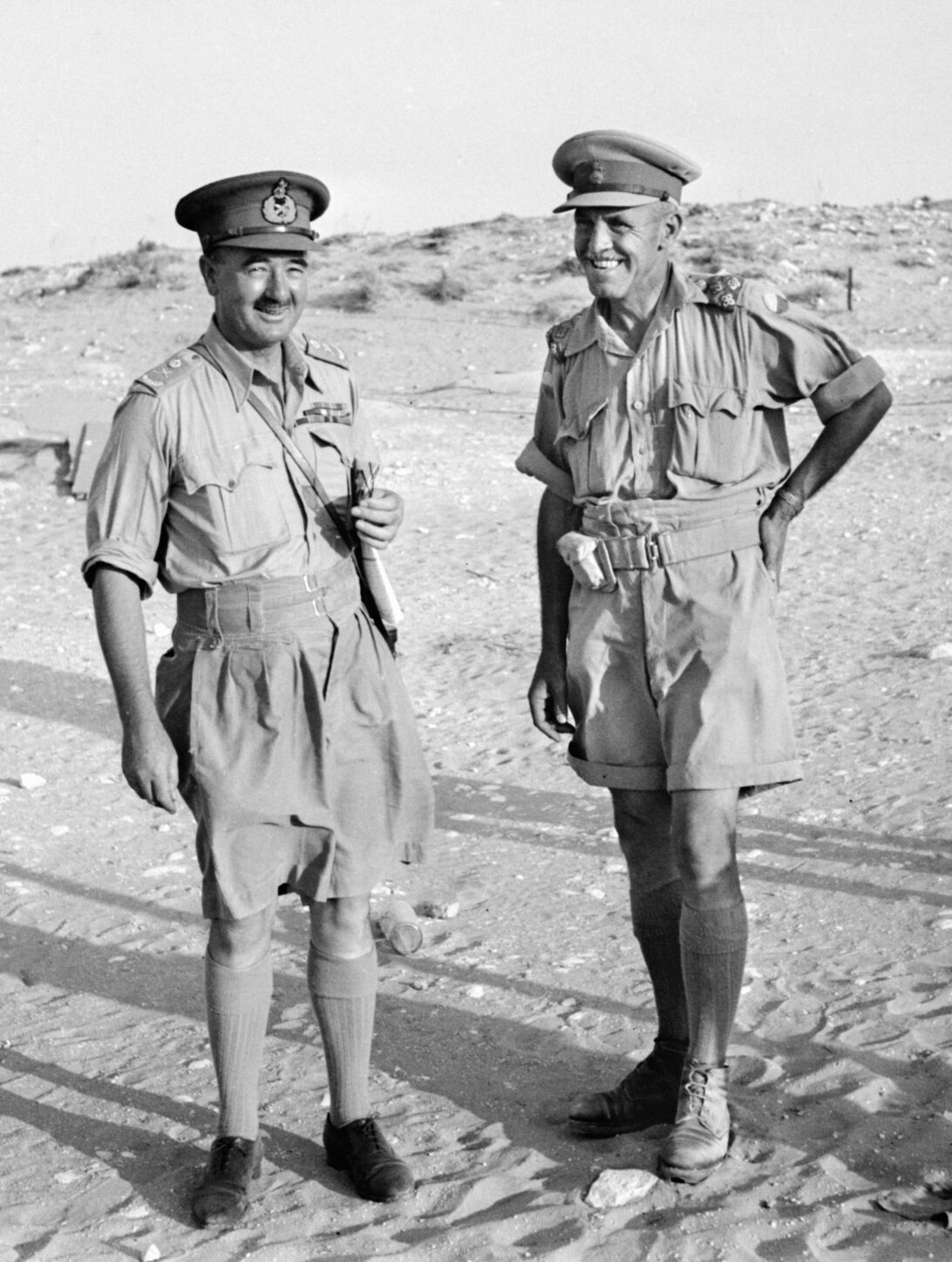

O’Connor, promoted to command all British troops in Egypt, was posted to Cairo. By late March, alarming intelligence reports soon proved more than reliable as a new and deadly player appeared on the scene, having disembarked at Tripoli with two tank divisions. This was enough to send the newly appointed British military governor of Cyrenaica, Lt. Gen. Philip Neame, packing off due east with his entire headquarters. Ordered to race back to Cyrenaica to assist Neame, O’Connor had the wretchedly bad luck to run straight into an errant enemy patrol. The forward scouts quickly surrounding the jeep were cut from a different cloth altogether than the decidedly lukewarm Italians. Barking their orders with a deep, guttural menace as they surrounded their prize, they were armed with the latest German submachine guns, which they proceeded to level at the jeep’s forlorn occupants in deadly earnest.

The Germans had officially arrived in North Africa. For the unfortunate O’Connor, the war appeared to be over as it had barely begun. However, as the see-saw shooting match in the desert heated up anew, an unlikely band of heroes would soon capture the imagination of a world already weary of war and badly in need of hope.

In what was, at first, a sort of anachronistic sideshow of the war, the tenacity and courage of a hardy cohort of sun-baked diehards captured the attention of the world and scored a strategic victory that almost singlehandedly stopped the German juggernaut in its tracks and rolled back Mussolini’s annexations. In retrospect, it was, arguably, the turning point of the war, and it came in the desert at a place called Tobruk.

On June 10, a scant four days before Nazi troops entered Paris, Hitler’s ally and fellow dictator, Mussolini, decided that it was safe at last for Fascist Italy to declare war on France. For good measure, having seen the British Expeditionary Force chased back across the English Channel from the beaches of Dunkirk the week before, it seemed like a safe bet to declare war on Britain as well.

After standing on the sidelines watching with an increasing envy as the battering ram of the German military machine succeeded beyond the wildest dreams of its Wehrmacht architects, Mussolini became increasingly eager to get more out of the four-year-old Pact of Steel than the dubious honor of merely basking in the reflected glory of a Nazi victory.

What Mussolini wanted most, apart from upping his prestige, was more territory to expand his insufferably grandiose pretensions to empire. With the prospect of a quick land grab in the offing at the expense of an already prostrate France, Mussolini threw in his lot with Hitler. For his troubles, he could boast a postage stamp-sized corner of the French Riviera, but with his enormous ego bristling over his puny gains, Il Duce was soon setting his sights on bigger game.

Libya, or Italian North Africa, as it was then officially known, had been wrested from the dying Ottoman Empire in the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-1912. Initially comprising little more than the port of Tripoli and its outskirts, its territory had been steadily and painstakingly added to in the years that followed, including a generous allotment of empty desert ceded to Italy in the 1920s by her friendly neighbors next door in British Egypt.

With England hard pressed to defend her own shores, much less make a stand anywhere else, it was to the east, in Egypt, with hungry eyes and dreams of martial glory, that Mussolini now cast his gaze. To Il Duce, it must have seemed like easy pickings.

The brutal Italian General Rodolfo Graziani was decidedly less than hot blooded when it came to the prospects of an Italian victory, easy or otherwise, in a war with the British, but Mussolini was determined to roll the dice, impatiently exhorting the commander in chief of Italian North Africa to commence operations by August 8, 1940. On September 13, Graziani took the bit in his teeth, albeit reluctantly and from the safety of his headquarters, ordering no less than the five cobbled-together divisions of the lumbering Italian Tenth Army eastward toward the Egyptian frontier.

Underequipped and patently obsolete by the standards of the day, the invasion force tasked with carrying out Operation E (for Egypt) was only partially motorized, with foot soldiers slogging along behind a spearhead of aging tanks. Advancing along the only practical route open to them, the sliver of territory between the Mediterranean Sea on their left flank and the Sahara on their right, the Italian column nevertheless managed to penetrate 59 dusty miles inside Egypt before deciding, while their luck still held, to halt their advance in the bedraggled precincts of Maktila. From there, they set about constructing a series of heavily fortified cantons stretching back along their route, dug themselves in, and waited for resupply and reinforcements.

And there they sat, waiting under the blistering desert sun, tormented by flies and desert scorpions, their foodstuffs and water supply, which were inadequate from the start, rapidly dwindling. The British, for their part, were content for a time to let them wait. Then, on December 9, they lowered the boom. Under the command of the redoubtable O’Connor, 30,000 British regulars, Australian, and Indian Army troops pounced on their hapless enemy and proceeded to kick the tar out of them.

This is not to say that the individual Italian soldier was not brave. He very often was. But, he was ill equipped, poorly trained and led into battle by an officer corps that was long on bravado and woefully short of tactical genius. Operating in one of the harshest environments on Earth without adequate shelter, food and especially water, unit cohesion, indeed military discipline itself, simply broke down, and he cracked.

Codenamed Operation Compass, the British offensive was designed to not only push the Italians completely out of Egypt, which they soon did, but to press the attack all the way back into Libya and seize control of the great camel’s hump of the Libyan coastline. This was vital, because in doing so the British would be able to capture the enemy’s strategically invaluable ports, making them masters of the narrow 1,100-mile track, west to east, between the Libyan ports of Tripoli and Tobruk and the Egyptian port of Alexandria.

It was through this single crucial artery that any army, friend or foe, operating along the North African coast would depend for reinforcements and the resupply of tanks, guns, ammunition, artillery pieces, munitions, spare parts, food, medicine, and all manner of war matériel coming in via the shipping lanes of the Mediterranean Sea. Once in port, the precious supplies would necessarily have to be trucked through the daunting, scorching wilderness to the waiting troops.

As the Italian Tenth Army fell back in utter chaos and confusion, the soldiers, mostly bewildered conscripts, began surrendering by the bushel, throwing their hands up with unabashed abandon. On January 22, 1941, the 25,000-strong Italian garrison charged with holding the prized central port of Tobruk threw in the towel after a day and a half of pounding courtesy of the Australian 6th Division, which lost about 50 men and another 300 wounded to capture the city.

The zeal with which the Italians in every sector tossed away their carbines and literally rushed to cheerfully surrender themselves to the care of their pursuers took the astounded British professionals completely by surprise and actually began to seriously impede the progress of O’Connor’s battle plan. By the time they were compelled to halt their advance at the dusty coastal village of El Agheila in February 1941, the British had rammed their way 500 miles into Libya and bagged 133,000 prisoners, a huge, unwieldy number, for whom they were now responsible, taken at a cost of 2,000 British and Imperial troops killed or wounded from December 1940 to February 1941. No one could have dreamed in those heady days that O’Connor would be a prisoner himself within a matter of weeks.

The entire Italian Tenth Army had surrendered by the end of February, and the whole of the enormous province of Cyrenaica was in British hands. The plan was to regroup and push on to Tripoli. Then the politicians became involved. With the Italian Army seemingly all but finished in North Africa, Churchill began denuding the cream of the British forces, including O’Connor’s XIII Corps and the crack Australian 6th and New Zealand 1st Divisions, diverting them to Crete in a fruitless attempt to stymie Axis intentions in Greece and elsewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean.

This was, in retrospect, one of the most stupid decisions of the entire war because by that time Hitler had already dispatched a German expeditionary force to Libya to pull Mussolini’s fat out of the fire, a mighty host, the lead elements of which began arriving in Tripoli on February 10, 1941. The Afrika Korps, led by Maj. Gen. Erwin Rommel, comprised the 5th Light Division, 15th Panzer Division, and 90th Light Infantry Division. Rommel and the Afrika Korps would achieve lasting fame for their victories in desert warfare.

Churchill’s notorious meddling may well deserve the lion’s share of the blame for what followed, but a good deal of the responsibility also rests with the astonishing failure of military intelligence in Egypt to adequately appreciate the gravity of this looming threat and to properly convey that danger to Whitehall and Downing Street. Ultimately, that responsibility lands in Alexandria, on the desk of General Sir Archibald Wavell.

As the senior officer and commander in chief of British Forces, not just in Egypt, but the entire Middle East, Wavell should have been able to make better use of the human assets on the ground and the burgeoning warren of wartime intelligence analysts available to him to provide both himself and his superiors in London with a firmer grasp of the rapidly changing dynamics of their situation. He did not.

Seeing, in his view, no hard evidence to corroborate the reports he was receiving, Wavell saluted smartly and followed orders despite his misgivings and did nothing to dissuade his peripatetic prime minister from his foolhardy adventure in Crete, nor to safeguard his own flanks and the so recently won gains of his soldiers in the face of the gathering storm in Tripoli.

On March 24, Rommel struck hard. In two weeks of bloody jousting in the parched, arid, hardscrabble arena that became his killing ground, he turned the tables on the already well worn and now threadbare British forces.

Appearing and disappearing as if from nowhere, outflanking them at every turn, Rommel’s swift panzer columns succeeded in pushing the British straight out of Libya, sending them reeling back in disorder across their own lines in half-stunned retreat, over the border into Egypt.

Despite his earlier blunder, in this hour of crisis Wavell, to his credit, was nevertheless able to see the broader strategic picture and act accordingly. Having failed to take Tripoli when it was so very nearly within his grasp, a simple glimpse at the map of the Mediterranean Theater quickly told the old soldier all he needed to know.

Wavell knew the British would have to hold Malta, which was a vital supply hub in the Eastern Mediterranean. Beyond that, safeguarding Alexandria and the Suez Canal was absolutely essential. Lose them and lose all. But the shortest route to the desert and the men fighting for possession of it was dead center, between Tripoli and Alexandria. The linchpin, squatting on the North African coastline like the central connector in a life-or-death daisy chain was the port of Tobruk. The British had taken it in just over a day. Now they had to keep it.

Though his columns were in the midst of a headlong retreat back into Egypt in the middle of a sandstorm, Wavell ordered the very competent Lt. Gen. Leslie Morshead and his battle-tested 9th Australian Division to remain behind along with a contingent of British soldiers, which amounted to a combined force of 35,000, to defend the port. Morshead and his men would be expected, for the sake of Britain, the empire, and the fate of the free world, to hold Tobruk until their last breath. They would have no immediate prospects of relief and only machine guns, artillery, and fewer than 50 tanks to hold back the Germans.

To protect the port itself and its all-important harbor, the Italians had earlier constructed a system of concrete fortifications on the broad, rocky escarpment directly to its rear, which the Australians feverishly set about improving. The entire defensive area, being nearly 16 miles long and about 11 miles deep, had to defend a perimeter that stretched on for some 32 miserable miles worth of Libyan dirt.

When the Aussies were done, the frontline defensive belt, christened the Red Line, had an interconnected series of concealed trench lines bristling with barbed wire and interspersed machine guns linked to a network of thick concrete strongpoints dug down into the rocky sand, one for about every 1,000 feet. These partly concealed, roofless, mini pillboxes functioned in part like abbreviated blockhouses and were large enough to hold between 30 to 40 crouched defenders.

Augmenting the Red Line, a partially filled in antitank ditch, another gift of Il Duce’s minions, seven feet deep in some places, ran east-southeast along the eastern outskirts of the perimeter. Twenty-two miles deep inside the Red Line, protected by still more wire and several minefields, was the inner defensive ring, the Blue Line, yet another network of trenches and strongpoints, bringing their number to nearly 150, constructed of the very finest Italian concrete and now fortified by British military engineering and 12 battalions of Australian muscle.

Around April 10, Rommel’s confident soldiers, bolstered by a sizable number of Italian troops, arrived in force expecting to easily recapture their prize while simultaneously racing eastward to smash their way through the hastily thrown up British defenses, take Egypt by storm, and seize the beckoning Suez Canal.

Rommel expected his troops to take Tobruk in a day, just as the unfortunate O’Connor had done before him. The only trouble was that nobody had bothered to tell that to the Australians, who were not quite as ready to roll over as Mussolini’s conscripts had been just three months earlier. In fact, on April 13-14 when Rommel sent in elements of his 5th Light Division under cover of night for a desultory poke at Morshead’s defensive line at a spot just west of the roadway called El Adem (literally “the end,” in Arabic), the Aussies handed them their heads.

The Germans initially managed to punch a hole through the Red Line positions held by the men of the 17th Battalion of the 2nd Infantry Regiment. But when the Italian Ariete Division’s tanks pushed forward through the breach, they soon found themselves under the guns of the Royal Artillery defending the Blue Line. Subjected to a devastating barrage of 25-pound cannon shells and antitank fire, the Nazis and their Axis partners were compelled to beat an undignified retreat. When they shifted west and tried it again the next day at another point along the Red Line’s defenses, joined this time by the tanks of Italy’s Trento Division, they fared even worse. In addition to completely clobbering their foes, the Australians of the 2nd Regiment’s 48th Battalion bagged some 800 prisoners, mostly Italian.

For more than two weeks, the headstrong Rommel, still pushing east, seemed to take little notice of what was happening in his rear at Tobruk and declined to go full bore in pressing the attack. The Aussies made great use of the relative pause in hostilities, toiling like demons to continue to repair and improve their defenses, even as Luftwaffe bombers blasted the actual town of Tobruk nearly off the map and bombed and strafed the harbor, sinking several supply ships caught running the Mediterranean gauntlet.

Undaunted, Morshead, far from cowering in his command post, took the fight directly to the enemy nearly every night. In addition to constantly conducting reconnaissance in strength to inspect the defenses and take measure of the enemy—capturing absurdly large numbers of prisoners in the process—his patrols, often 300 men strong, slipped out under the desert night sky to deliver a dose of death in the dark.

By April’s end, the Aussies had managed to regain Rommel’s attention. So long as he was denied the use of Tobruk’s port, the vaunted Afrika Korps had to rely on an overstretched supply line extending several hundred miles west to east from Tripoli. Rommel’s grand offensive was literally and continually running out of gas.

On the afternoon of April 30, determined to remove this irritating thorn from his backside, Rommel unleashed his attack on Tobruk. After watching with great interest as a Luftwaffe squadron bombed the Aussie defensive positions from the air, he ordered an attack on the dugouts at the hilly southwest corner of the Red Line. With tanks from his 15th Panzer Division advancing on one side and the motorized 5th Division moving forward on its flank, the Germans renewed their attempts to blast open pathways through the concrete and barbed wire, through which the hapless Italians were expected to advance, straight into the teeth of British artillery and chattering machine guns like something out of World War I.

Despite the deficiencies of Mussolini’s army as a whole, the heroism of the individual Italian soldier was on full display. At one point, as the momentum of the attack bogged down, in a desperate bid to create a broader pathway for their own two divisions, the Ariete and the Brescia, respectively, Italian sappers braved withering machine-gun fire to plant the explosive charges that succeeded in blowing open huge holes in the wire, making the Axis advance possible. As for the Aussies in the trench lines, they resisted like wildcats, making the enemy pay for every dusty yard.

Following behind the Italian spearhead, the Germans sent their panzers racing north and east toward the Blue Line. Morshead and his men were waiting for them. What the minefields did not stop, the antitank guns blew to pieces. For good measure, Morshead risked a handful of the tanks he had been holding in precious reserve. The attack of May 1 lasted all day and well into the night, and for a full two days beyond that, forcing Rommel to throw in his reinforcements to blunt the numerous Australian counterattacks hell bent on tossing him off the two miles of blood-soaked desert corridor that his vehicles attempted to cross.

At that point, the Germans, stunned and staggered by the fierceness of their enemy, and unaccustomed as they were to not getting their way, grudgingly took their cue from the insults being hurled at them from the Aussie trenches. By May 3, the hitherto victorious Germans were breaking out their spades and digging in for the long haul themselves. In this sector in particular, known to history as “the salient,” it was man against man, trench against trench, and foxhole against foxhole, in a lethal faceoff that was destined to go on for months.

For the defenders, food, remarkably enough for an army of 35,000 men under siege, was relatively plentiful if far from luxurious, canned fruit, salt beef, and biscuits being the order of the day. It was a shortage of fresh water that rankled almost as much as the enemy. Despite the presence of two wells and a preexisting desalination plant left by the Italians, water soon became an extremely scarce commodity for these men enduring months in the relentlessly scorching desert conditions. Even for the Aussies, proud as they were of their Outback heritage, it was tough going. The daily ration was a pitiful three pints.

Moreover, in the Red Line sectors the men were effectively pinned down. Venturing out of their barely concealed positions, even poking their heads up a little too high for a little too long from a narrow slit trench was like suicide, and the Diggers, as they called themselves, farther back in the Blue Line soon learned that being caught out in the open, particularly for those foolish enough to congregate in clusters or groups, might soon provoke a strafing or bombing run.

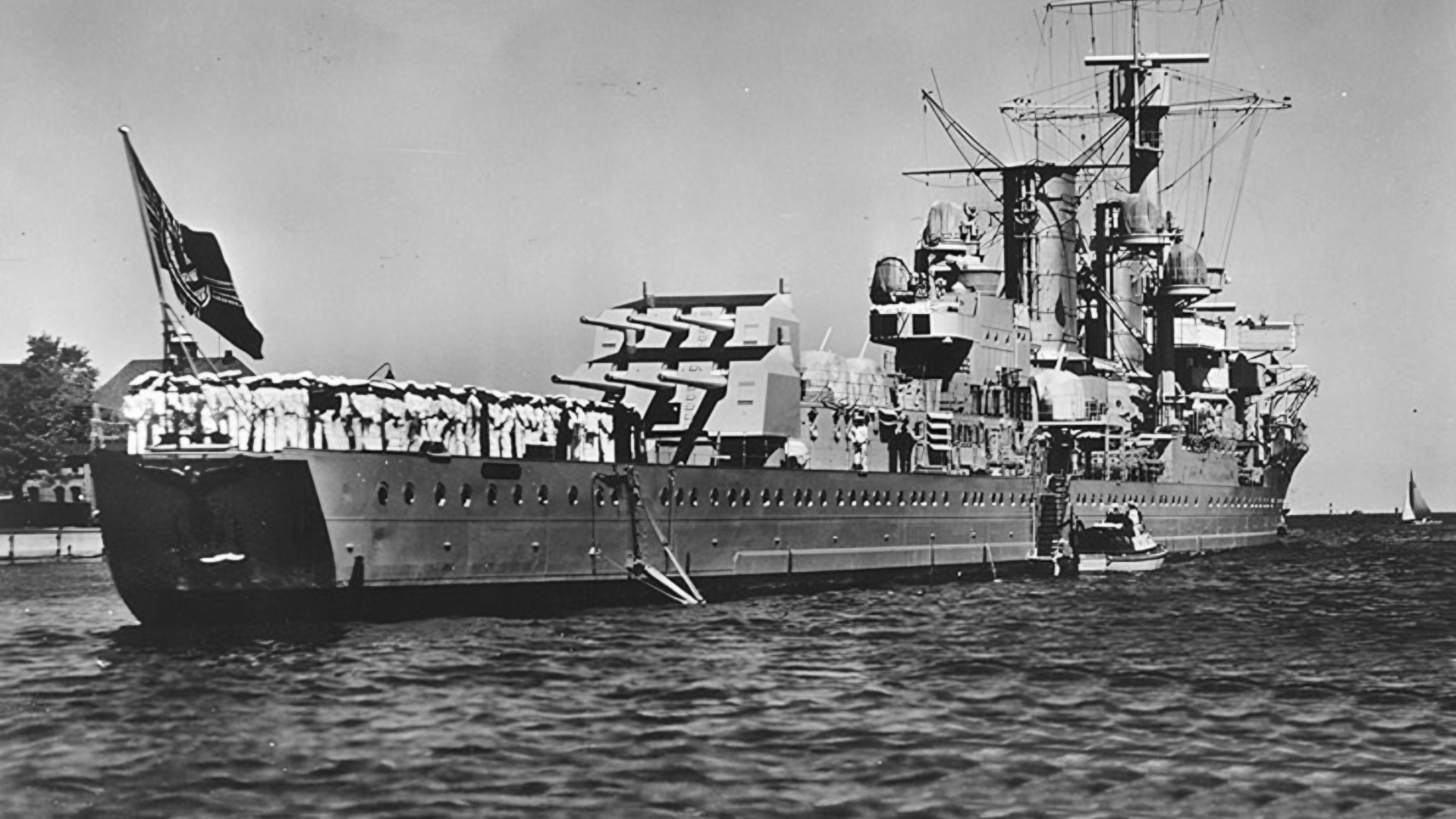

The ships of the British Royal Navy operating out of Alexandria quickly came to prefer the cover of dark, moonless nights when it came to resupplying the Tobruk garrison, as did the wide variety of other vessels pressed into service. Hugging the coastline, slipping into the harbor as quietly as possible (no easy feat) and getting back out again—before dawn if they could—everything from a destroyer or minesweeper to the smallest of seagoing craft was used to keep the vital lifeline open.

The ships making this perilous run were subjected not only to magnetic mines, but also to direct and constant attack both from the air and from the sea by German U-boats and E-boats near the shore. The Luftwaffe pilots, operating out of bases in Italy and Tripolitania, were particularly vicious, bombing cargo craft and hospital ships alike, Red Cross markings and the Geneva Convention be damned.

The harbor was soon filled with half-sunken hulks, which the ever resourceful blockade runners sailing west from Egypt soon began using as cover. For all the bravado associated with it to this day, the resupply of Tobruk’s indefatigable denizens was an incredibly dangerous, deadly bit of business. In due course, most of the troop movements in or out, including battlefield casualties, became the purview of the heavily armed destroyers.

Within the garrison’s defensive rings, as time wore on the seemingly endless ordeal made for a maddening experience. Apart from those who considered themselves fortunate enough just to be alive, the luckiest men in Tobruk were the troops stationed in the rear, who were posted within the bomb-blasted ruins of the town. They, and the crews that manned the antiaircraft guns who were given leave to join them there once a week, were among the happy few who were afforded the opportunity to go down to the sheltered beaches for a cooling, cleansing dip in the surf. For the men manning the defenses at the Blue Line, and especially the lethal forward positions at the Red Line, however, it was no such luck.

Sensibly, Morshead failed to live up entirely to his sobriquet in this regard, as it quickly became routine policy to rotate his soldiers between the murderously exposed Red Line, the relatively less deadly Blue Line, and the troops stationed behind them in reserve, who functioned like a continuously operating labor battalion.

Moreover, despite Morshead’s best intentions, the troop rotations could only provide a temporary respite at best for his exhausted soldiers, and there was no relief in sight. For the men in the frontline trenches, continuously exposed to the elements and facing direct fire from the enemy, the prospect of being picked off by snipers, the omnipresent threat of aerial attack, artillery bombardment or a full-fledged frontal assault, life devolved into a nightmare. Even the parched, cracked, seemingly dead soil of the Libyan desert itself proved a constant torment with eye-pecking swarms of disease-carrying flies, mosquitoes, sand fleas, Saharan beetles, and desert scorpions.

In addition to the specter of heat exhaustion, heat stroke, and dehydration, the greater part of the garrison was invariably plagued by still another desert scourge, the painful sores that erupt upon the flesh of men whose diet is devoid of the essential vitamins and nutrients so easily found in fresh fruit and vegetables.

The conditions at the siege of Tobruk proved so appalling that an informal, officially unsanctioned soldier’s truce eventually came into being for two hours every evening as the boiling sun went down at last and day made its transition to night. The combatants on both sides used this time to gather water, rations, quinine, and all manner of supplies, including ammunition. They also used it to answer the call of nature or simply to emerge from the cramped confines of their dusty, sand-choked trenches for the first time in 12 long hours, stand up straight, and stretch their aching legs, crooked spines, and stiff necks. With typically Teutonic punctuality, the Germans would, very obligingly, shoot off a clip of tracer bullets into the night sky to alert their opposite numbers in the Australian Red Line when the particular evening’s nightly cessation of hostilities was thereby concluded.

This anachronistic code of martial chivalry extended in part to daylight hours as well, as the Aussies and the Germans came to develop a simple but very effective method for getting their wounded out of the killing zones. If one side or the other began waving a simple flag adorned with the symbol, however makeshift, of the International Red Cross fashioned upon it, the soldiers on the opposing side would make certain not to open up on the medics and the stretcher bearers, contenting themselves with blasting away at other less vulnerable combatants until the wounded were safely out of the way.

This is not to say that as the weeks ground on and the long, endless, blistering heat of North Africa slowly began to boil Brit and Boche alike, that a deep, burning enmity was not broiling away as well in both camps. Something in the Australian character hardened Tobruk’s defenders, filling them to a man with a dogged determination to stand up and prove that they could take it. Long derided as the backward spawn of a colonial backwater, the Australians were now showing the enemy and the world what real backbone looked like.

Their ancestors, mostly Irish, had been hauled away in chains to the edge of the world on death ships, only to be marooned in a howling wilderness, but within a few generations they and their descendants had managed to turn expulsion and exile into a kind of frontier glory, carving a new homeland and a national identity out of what was a penal colony in one of the most inhospitable places on Earth. Now, that hardy bloodline and same indomitable spirit spurred on these defiant men, who mocked and railed against the accursed Germans and dared them to do their worst.

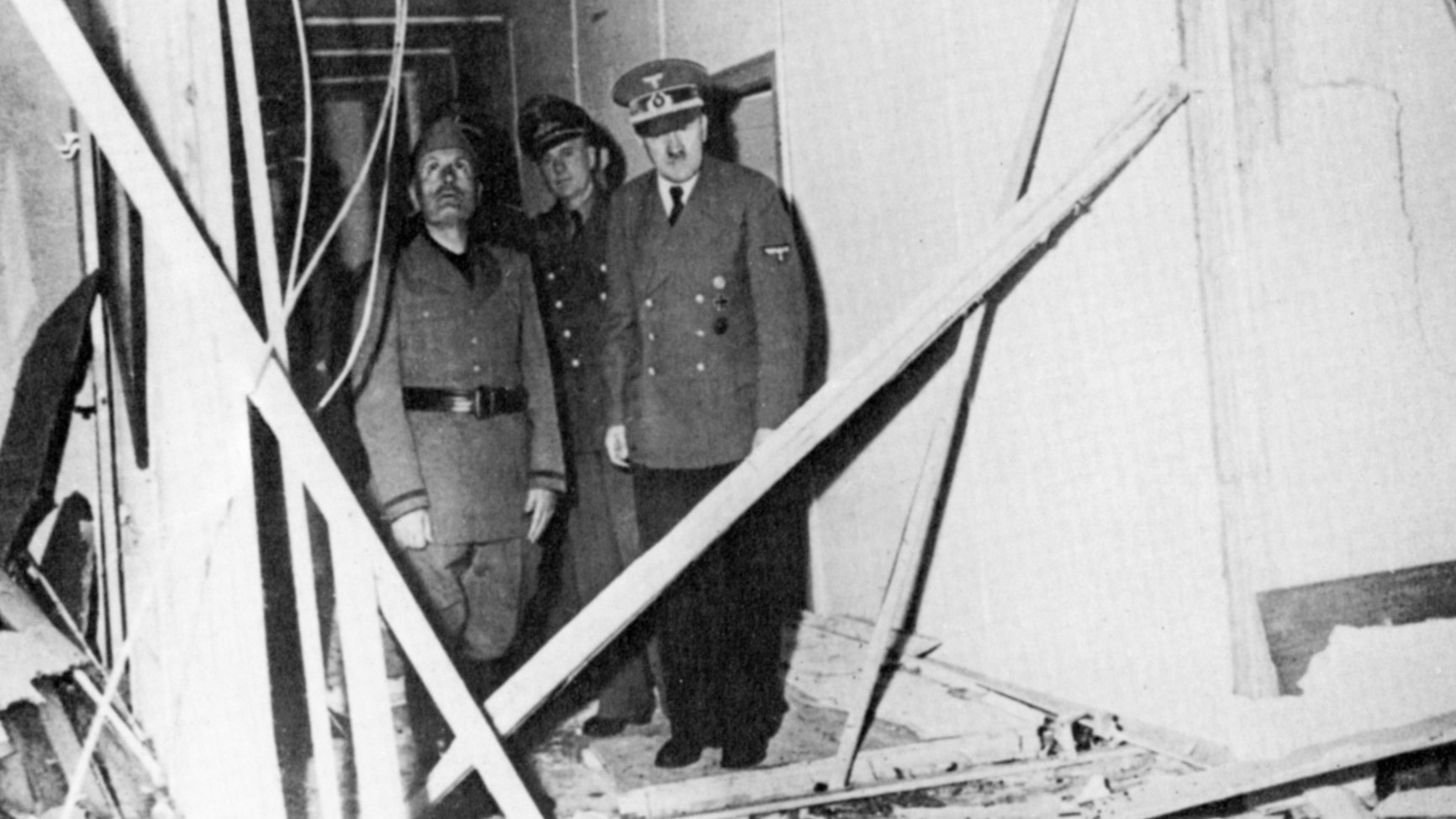

For their part, Nazi fury and frustration in the face of the stubborn garrison’s continued refusal to knuckle under increased with the passing of every desert day. Back in Berlin, at the daily situation conferences, Hitler demanded to know whether or not he could proclaim himself the master of the Mediterranean.

In the newsreels and on the radio, venomous insults began to pour out of the poisoned pens of the increasingly shrill Nazi propaganda machine, with no less a miscreant than the whiskey-swilling, erstwhile British Union of Fascists Hitlerite “Lord Haw-Haw” practically snarling into the microphone during his nightly English language rants, assailing the beleaguered Australians under siege in the Libyan desert for daring to defy the Nazis, burrowing down in the dirt of their grimy slit trenches as if they were a mangy pack of half dead dogs defending their own shallow graves. It was he who first dismissed Tobruk’s gallant defenders as being “trapped like rats.” The Aussies just laughed at the insult and ran with it. The men who called themselves Diggers now happily began to refer to themselves with a wink and a nod as the Rats of Tobruk. History has saluted them as the Desert Rats ever since.

In the third week of May, Wavell, spurred to action by Churchill, launched the appropriately named Operation Brevity, sending his tanks west toward Tobruk, but they were immediately checked by Rommel’s superior panzers and badly mauled in the process. For their part, the Aussies were able to thwart German attempts to push farther north from their positions in the Red Line’s bulging salient and make for the Blue Line defenses. In ferocious fighting, the Australians stopped them cold. Several counterattacks launched by Morshead on the 17th drove home the lesson, but he lost many good men making his point. The Saharan summer had only just begun.

A month later, with Churchill braying in his ear, Wavell tried again with still more tanks and more Tommies, launching Operation Battleaxe, but Rommel, after running rings around the British tank columns in the sands of the Halfaya Pass, proceeded to make mincemeat out of them when he unleashed his secret weapon, a battery of antiaircraft guns reconfigured for ground operations. In their battlefield debut, the dreaded 88mm guns proved to be excellent tank killers. Rommel’s counterattack on June 17 sent the surviving British tankers reeling in retreat. Wavell was recalled shortly thereafter.

Rommel, too, was beginning to run out of steam. He could still spring up like a sandstorm to wreak havoc up and down the frontier like a desert bogey man, but denied his port and his petrol, Alexandria, Cairo, and the Suez Canal remained, like a desert mirage, just beyond his reach. By summer’s end, after holding out for over four grueling months, Tobruk had become an important psychological symbol, a morale booster for the British Empire and its war effort. Its Aussie defenders had to be saved at all costs.

In August, pressured by the Australian government, Churchill, aware of their propaganda value, issued the order from London. Tobruk would remain British, but the time had come for its Australian garrison to be relieved. Getting the Aussies out and their replacements in without tipping off the Germans was a difficult exercise. It took more than two months, but by the end of October the Aussies were nearly all safely evacuated, and command passed from Morshead to Lt. Gen. Ronald Scobie and his British 70th Division. On December 7, 1941, as part of Operation Crusader, South African troops and the British tanks of the Eighth Army appeared on the horizon to link up at last and relieve Scobie’s command. The 242-day siege of Tobruk was history.

In the spring of the following year, Rommel would return to Tobruk.In the spring of the following year, Rommel would return to Tobruk. In a fresh offensive that began in May 1942, Rommel successfully captured the port on June 21 by outflanking British forces. However, the tide of war gradually turned. In November 1942, Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery won a decisive victory over Rommel at El Alamein. Then, caught between American and British pincers, the Germans were driven out of Africa once and for all in May 1943. Nothing remained of the Nazis in North Africa save the memory of their fleeting triumphs.

The 88 mm anti-aircraft gun in the ground anti-tank role was not a secret at this time. Rommel had used them on 21 MAY 1940 at Arras, France, to repel the 4th and 7th Battalion’s Matildas, Royal Tank Regiment when he was commanding 7th Panzer Division. It was not the 88 mm’s battlefield debute and already was known to British tank officers in the desert some of which had already suffered from them in France.

It is a pity that the Fellers affair is not mentioned in which the US military attache in Cairo unknowingly gave Rommel highly detailed and timely information on all allied plans, positions, strengths, etc. on a daily basis for the first six months of 1942 which of course helped the desert fox immensely!

For a story on the Battle of Arras, and the British encountering the 88 as an anti-tank weapon, you might try this story:

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/armored-strike-at-arras-counterattack-against-the-blitz/