By Arnold Blumberg

During the afternoon of October 9, 1973, Colonel Amnon Reshef, the commander of the Israeli Defense Force’s (IDF) 14th Armored Brigade, conducted probes along the water’s edge of the Great Bitter Lake, a wide part of the Suez Canal. Temporarily attached to Maj. Gen. Ariel Sharon’s 143rd Reserve Armored Division, along with that division’s reconnaissance unit, Reshef’s advance patrols had reached the so-called Chinese Farm located just north of the Great Bitter Lake, on the east side of the Suez Canal and five miles east of the town of Deversoir, which sits on the west bank of the canal. The Chinese Farm was an experimental agricultural area used by Japanese instructors before the Six-Day War fought in 1967. Viewing Japanese inscriptions on the walls, Israeli troops, not particularly well versed in East Asian script, named the place Chinese Farm.

On the morning of October 10, Reshef’s advance forces were ordered by the Israeli high command to withdraw from the immediate region of the Chinese Farm. The reason was that—unknown to the Egyptians—the IDF had been alerted by intelligence from U.S. spy planes of a gap between Maj. Gen. Mohamed Sa’ad Ma’amon’s Egyptian Second Army and Maj. Gen. Mohamed Abd El Al Mona’am Wasel’s Third Army. The Second Army was composed of the 2nd, 16th, and 18th Infantry and 21st Armored and 23rd Mechanized Divisions, and Third Army comprised the 4th Armored, 6th Mechanized, 7th Infantry, and 19th Infantry Divisions. The two armies had crossed the Suez Canal on October 6, 1973, at the start of the new war.

Since the commencement of the conflict the Israelis had debated the wisdom of crossing the Suez Canal as part of their counteroffensive to hurl the enemy back over that waterway. Reshef’s probe of the thinly held boundary between the two opposing armies would be the key to the final decision to attempt the passage and thus turn what had been up to that time a possible Israeli military defeat into national salvation and victory.

Humiliated by the stunning and rapid victory achieved by Israel over her Arab neighbors (i.e., Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) during the Six-Day War in June 1967, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on October 6, 1973, against Israel on Yom Kippur, one of the holiest days on the Jewish calendar. The aim of Operation Badr was to take back territory lost in the Six-Day War. Egypt sought to recover the Sinai Peninsula, and Syria sought to retake the Golan Heights.

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat planned to send his Second and Third Armies into the Sinai. The two armies comprised five infantry divisions (each of which was supported by an armored brigade), three mechanized, and two armored divisions. Altogether, Egypt had massed 200,000 men, 1,600 tanks, 2,000 pieces of artillery, 100 SAM batteries, and 300 aircraft for the assault across the Suez Canal.

The assault began at 2 pm, October 6, under a protective umbrella of Russian SAM-2, SAM-3, and SAM-6 antiaircraft missiles. Within hours Sadat’s army had secured lodgments over 55 miles of the 110-mile-long waterway.

Facing the attackers on the first day of the 1973 Yom Kippur War were 436 men of the Jerusalem Reserve Infantry Brigade. These inexperienced soldiers manned a series of fortifications seven to eight miles apart called the Bar-Lev Line. The Bar-Lev Line featured 30 strongpoints on the east bank of the Suez Canal, each screened by a sand bank several yards high equipped with small arms, machine guns, and mortars. At the outbreak of the war, 16 of the works were fully garrisoned, two partially so, with the remainder closed or held by only small observation teams.

Acting as a backstop to the Bar-Lev Line was a small infantry brigade holding the northern marshland reaches of the Canal Zone, and Maj. Gen. Avraham Mandler’s 252nd Armored Division, which comprised three armored brigades: Colonel Amnon Reshef’s, Colonel Dan Shomron’s, and Colonel Gavriel Amir’s 14th, 401st, and 460th, respectively. But the bulk of the latter formation, which numbered 13,000 troops, 280 tanks, and 80 guns, was being held as an immediate reserve in the eastern Sinai, ready to be activated by the trip wire of the Bar-Lev Line. It was intended as merely a holding force until the rest of the army could be mobilized and sent south, which was expected to take 48 to 72 hours. The Syrians launched a simultaneous attack against the Golan Heights on Israel’s northern border.

Following the Six-Day War, Israeli military analysts attributed success in that conflict to only two elements of their armed forces: the air force and the tank corps. As a result, those branches of the IDF received 50 percent and 30 percent, respectively, of the massive defense budgets appropriated annually after that war. This left little for the infantry, artillery, and quartermaster corps. The Israeli Air Force (IAF) concentrated on acquiring sophisticated American fighters and fighter-bombers, as well as impressive arrays of ordnance and advanced radar equipment. The Army purchased new British and U.S. tanks and improved its existing armored fighting vehicles with upgraded equipment. The result was an unwarranted overconfidence in the ability of the aircraft and armor combination to defeat all opponents. Since planes and tanks had been so successful in the Six-Day War, the Israeli military believed it wise to invest heavily in both weapons for future conflicts.

As early as 1970, the Egyptian Army decided to abandon attempts at mimicking the swift movement of the Israeli blitzkrieg tactics. Instead, the Egyptian Army developed a new strategy that employed new tactics. The shift to a new strategy was based on Egyptian War Minister General Ahmed Ismail’s trenchant assessment of Israel’s strategic weaknesses. “His lines of communication were long and extended to several fronts, which made them difficult to defend,” said Ismail. “His manpower sources do not permit heavy losses of life. His economic resources prevent him from accepting a long war. He is, moreover, an enemy who suffers the evils of wanton conceit.”

Israel’s blitzkrieg tactics were intended to minimize the Jewish State’s disadvantages by conducting a swift war with a low casualty rate. Ismail intended the Egyptians to wage a prolonged war that would be costly to Israel’s economic and human resources while minimizing its advantages. To do this, Egypt needed to come up with new battlefield stratagems designed to counter any Israeli blitzkrieg. “[We] did not want to be conventional,” Ismail said afterward.

To begin with, it was admitted that Egyptian Air Force pilots did not have the skill to match their Israeli counterparts in aerial combat. Moreover, they flew inferior Soviet aircraft compared to the Western models used by Israel. Thus missile screens—in the form of massed batteries and infantry weapons like the shoulder-fired, low-altitude SA-7 Strela heat-seeking missile—were created to offset Israel’s advantage in the sky. If the IAF could not soften up the enemy, the IDF would have to use artillery to do so.

But Israel had not significantly expanded its artillery capability since the Six-Day War, and it was again found lacking throughout the 1973 conflict. The result was that Israeli ground attacks were preceded by insufficient artillery preparation. On the first day of the war the IAF lost more than 20 aircraft attempting to knock out Egyptian bridges across the Suez Canal and SAM battery sites. For the entire war, 95 percent of the IAF’s losses were to enemy air defense systems. This missile umbrella virtually nullified Israeli air power, making impotent one-half of the blitzkrieg formula.

On the ground the Egyptian tactics were even more unique than their air defense system. After a well-prepared crossing of the Suez Canal, borrowed straight from Soviet military textbooks, both the Russians and Israelis were confounded by the way the Egyptians then went about deploying their armies. Normally, specialist troops would seize a bridgehead with enough infantry to reinforce it before masses of tanks would pour across to charge into enemy territory. The Egyptians did not follow this orthodoxy. Instead of concentrating against a few selected points of their enemy’s position, they threw their bridges over the 100 miles of canal along its entire length from Port Said to Suez. The objective in doing this was to force the Israelis to disperse their efforts along the whole front.

Once over the waterway, Egypt’s forces did not immediately thrust eastward but moved north and south to form a long, continuous bridgehead only six to 10 miles deep. The missile-armed infantry marched into the Sinai Desert and took up defensive positions, while SAM-6 and ZSU-23 antiaircraft batteries deployed near the canal and farther west. Next, the Egyptians waited for the Israeli response, in the form of a blitzkrieg counterattack, which they knew would surely come soon.

The cleverness of Ismail’s plan was in its combination of two distinct elements of warfare not seen previously. The single major stride across the canal was strategically an offensive move of the most aggressive sort. But Ismail then consolidated this by defensive tactics. The Egyptian foot soldiers just entrenched with their missiles. The combination played to the strength of the Egyptian Army, which always had been tenacious in defense, while at the same time avoiding its long-standing inability to conduct a war of maneuver.

The novel Egyptian tactics also capitalized on the Israeli belief that the only fitting way for a tank commander to behave was to charge ahead. To stop the Israeli tank attacks, the Egyptians were relying on a combination of AT-3 Saggers and RPG-7s. The Sagger was an antitank missile that could be carried and operated by a single soldier. The operator used an optical sight and manually steered the wire-guided missile to its target. The Sagger’s 5.7-pound warhead could penetrate eight inches of armor at a range of two miles. Waiting in the sand dunes the Egyptian infantry could easily hide until ready to fire on the unsuspecting Israeli armor from ambush.

The IDF was ill-prepared for this new kind of combat, which was not a dashing war of movement but instead a slow methodical slugfest. The IDF’s primary tank in the Yom Kippur War was the American M48A3 (known in Israel as the Magach-3) outfitted with the 105mm L7 gun, although it also had M60A1 (Magach-6) tanks. The Egyptian Army in the Sinai was equipped with Soviet T-55s with a 100mm gun and T-62s with a 115mm gun. The Israeli tanks in the Sinai initially carried armor-piercing rounds, which were fine against tanks if they could find any but were almost useless against infantry. To combat the Egyptian infantry, high-explosive rounds were essential, but these were not available until the third day of the war.

What the Israeli tank crews also needed to counter the Egyptian missile-carrying foot soldiers was artillery and infantry. But those vital commodities were always in short supply since the prewar military budgets largely ignored those elements of the IDF ground forces in favor of tanks. To make matters worse, the initial Egyptian air strikes knocked out 40 percent of Israeli artillery in the Sinai at the start of the war.

What is more, IDF tactics in place after 1967 did not stress coordination between infantry and armor because the former was intended only to mop up what the latter left behind. This tenet pushed the Israelis to enlist and train too few infantry before the war, a fact that would hobble the IDF’s operations considerably through the October 1973 struggle.

Egyptian Chief of the General Staff General Saad el Din Shazli termed the type of war his army would prosecute in 1973 as the “Meat Grinder War.” As the grisly name implies, it was designed to kill Israelis more that it was to outmaneuver or defeat them in battle or gain ground. Considering that by the fifth day 300 of the 900 Israeli tanks committed to the Sinai front had been destroyed (about 200 by Saggers and RPG-7s, a few by aircraft, and the rest by artillery), the name seemed most appropriate.

The Meat Grinder War sought to turn the tables on the type of combat that tanks had been engaged in for more than 30 years previously; that is, shock effect and rapid movement—the basics of blitzkrieg. The tank could no longer protect itself and now fell victim to its former prey, the antitank-equipped infantryman. The missiles deprived the tanks of their shock capability, forcing a greater reliance on terrain for their survivability. Thus the value of firepower displaced shock action, cover replaced flowing movement, and slaughter substituted for superior maneuver.

The first phase of the Yom Kippur War, which lasted from October 6 to October 9, saw the Egyptians gain great success in their assault across the Suez Canal. By the morning of October 7, the battle of the canal crossings had been won at a cost of only 208 men killed and 20 tanks and five airplanes destroyed. In 22 hours the Egyptian Army had crossed the Suez Canal with 100,000 troops, 900 tanks, and 12,000 vehicles.

Although the Egyptians expected a significant Israeli response within eight hours of the initial crossing, the IDF had not been able to attack due to being caught off balance and having little armor in the tactical zone. This was because its reserves had not yet mobilized and moved to the battle area. Therefore, the Egyptians, who had thought their opponent would deliver his counterblow on October 8 or 9, dug in and awaited the inevitable Israeli assault. After repelling the expected enemy attack, the Egyptian forces were to undergo an operational pause starting on October 11 to allow them to consolidate and extend their long, shallow bridgehead while inflicting maximum losses on the IDF.

The Israeli high command, dominated by veterans of the Armored Corps and disciples of the doctrine of the concentrated armored assault, was not overly disturbed by the lack of success their tanks had had during the first two days of the war. To its way of thinking, the failure to rout the Egyptians up to that point was due to the piecemeal commitment of the tanks in platoon and company strength, which allowed the enemy—especially its well-trained and well-armed antitank-equipped infantry—to maul the Israeli armored fighting vehicles. It would be a different matter entirely, the IDF generals were convinced, when they were able to bring to bear brigade- and even divisional-strength tank formations.

To that end, two armored divisions—Maj. Gen. Avraham Adan’s 162nd Reserve (in the northern Sinai sector), and Sharon’s (in the southern sector)—would be employed to eliminate the enemy bridgeheads. The plan called for the Israelis to roll southward along the east bank of the canal. Adan was to strike from the area of El Qantara at the enemy Second Army, while Sharon remained in reserve near Tasa. If Adan’s attack went according to plan, Sharon would launch an assault south from the Great Bitter Lake against the Egyptian Third Army. However, if Adan’s part of the operation appeared to be failing, Sharon was to go to the former’s support. The real objective of the attack was muddled by some in the Israeli high command, who stressed that it was to break up the enemy lodgments on the east side of the canal, while others hoped the strike would be the first step in crossing to the canal’s western shore.

With sparse air support (most of the IAF was flying against the Syrians over the Golan Heights) and little artillery assets available to him, Adan attacked on the morning of October 8. By noon it was apparent that the Israeli plan had collapsed. At 2 pm the attack was halted. By that time, Adan, who had only 100 tanks in his division at the start of his assault, had lost dozens of tanks to effective Egyptian infantry armed with antitank weapons. Meanwhile, Sharon’s division had spent the day moving first south then north without exerting any influence on the unfolding battle.

The main effect of the fighting that day was that the IDF realized it had to conserve its strength and allow time for the reserve army to enter the field with all its supporting arms. Adan and Sharon had each lost 50 tanks from October 8 to October 9. Regardless of the gloom engendered by the results of the fighting on October 8, there was one positive element. Egyptian losses in infantry had been significant, and their plans to expand their bridgehead and move farther into the Sinai had been seriously disrupted.

Beginning on October 9, the Israelis set about stabilizing the Sinai front. During that time, the fighting grew in intensity. On October 10, the Egyptians launched five separate attacks against Adan, while Sharon warded off a strike by the Egyptian 21st Armored Division, which suffered the loss of 50 tanks. For the next few days stalemate reigned in the Sinai, but events on Israel’s northern border would materially alter the course of the war on that front.

By October 10 the IDF had pushed the Syrians off the Golan Heights, and the decision had been made by the Israeli government to drive the Syrians from the war by an advance on Damascus. Responding to this threat, the Syrians implored Egypt to launch an attack in the Sinai to relieve the pressure on their country. Responding on October 12, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, against the strenuous objections of Shazli, ordered an offensive from the canal toward the Gidi and Mitla Passes, which led from the Sinai to southern Israel.

The offensive ordered by Sadat was an unmitigated disaster for the Egyptian Army. Set in motion on October 14 using four separate axes of advance, the assaulting force was composed of four armored brigades and one mechanized brigade containing a total of 500 tanks. They faced 700 Israeli tanks, of which half were on the battle line and half in reserve. The Egyptian tank crews advanced against the Israeli armor across open terrain with the sun in their eyes. The Egyptian tanks were vulnerable to airstrikes since they were beyond the range of their antiaircraft missile umbrella. The IDF waited for them in well-prepared defensive positions on high ground. The Israelis had tube-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided antitank missiles recently purchased from the United States. As the sun rose in the early afternoon of October 14, the Egyptian Army was in full retreat back to its enclaves on the canal after losing 250 tanks. That single day’s number exceeded the 240 Egyptian tanks destroyed since the start of the war. In contrast, the Israelis lost only 20 tanks that day.

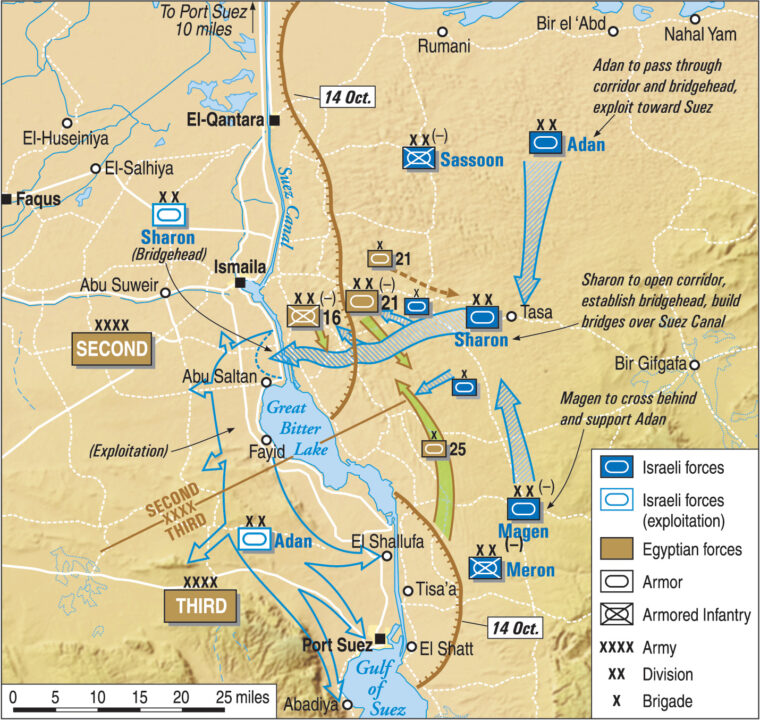

Determined to capitalize on the Egyptian repulse, Lt. Gen. David Elazar, IDF chief of staff, initiated Operation Stouthearted Men, which had as its goal the crossing of Israeli infantry and armor to the west bank of the Suez Canal to threaten the supply line of the Egyptian forces on the east bank. The operation, which was scheduled to begin on October 15, called for three armored divisions—Adan’s, Sharon’s, and Mandler’s, the latter by then headed by Brig. Gen. Kalman Magen, with 200, 240, and 140 tanks, respectively—to cross near Deversoir and then surround the Egyptian Third Army by capturing Suez City. For the crossing, Sharon’s 143rd Armored Division would secure both sides of the canal and the two roads, the Akavish and Tirtur, that led to the crossing site on the east bank. Adan would then take his 162nd Armored Division across and destroy the Egyptian air defense system, thus allowing needed Israeli close air support to come into play. If all went according to plan, Magen’s 252nd Armored Division would pass over the canal and relieve Sharon as Adan raced south to capture Suez City.

Based on the assumption that the Egyptians had reverted to their old form and that they had only 700 tanks posted on either side of the canal, Operation Stouthearted Men envisioned a one-day crossing with only an additional 24 hours to encircle the Third Army. As it turned out, this 48-hour timetable was completely unrealistic as the Egyptians would display remarkable defensive prowess even when confronted with Israeli units in their rear.

Sharon’s division was tasked with securing the access routes and crossing site and the creation of a bridgehead on the west side of the canal northward from the Great Bitter Lake. To carry out his mission, Sharon assigned Colonel Tuvia Raviv’s 600th Reserve Armored Brigade to launch a diversionary frontal assault along the Tasa-Ismaila Road on the strongpoint of “Missouri” just north of the Akavish Road and the Chinese Farm to pin down the Egyptian 16th Infantry Division. Raviv’s initial objectives were the “Hamutal” and “Machshir” sand hills. Thereafter, Raviv was to hook to the southwest and take “Televisa.”

An hour after Raviv started on his way, Reshef’s reinforced 14th Armored Brigade was to march through the sand dunes past the southern flank of the Egyptian positions blocking the Akavish and Tirtur Roads until it reached the Great Bitter Lake. After that it was to achieve three objectives. First, it was to secure the three-mile sector of the canal opposite Deversoir, including “The Yard” (a concealed gap in the sand rampart giving access to the canal). Second, it was to protect the crossing by capturing the Chinese Farm. Third, it was to clear the Tirtur and Akavish Roads to allow access by the bridging trains, which included a pontoon bridge and a massive 200-yard-long, 400-ton roller-bridge. The pontoon structure was to move along the Akavish Road, while the roller-bridge travelled along the Tirtur Road. Colonel Dani Matt’s 247th Reserve Paratroop Brigade, attached to Sharon and reinforced by 10 tanks, was to follow Reshef and cross the canal at 11 pm on October 15 and secure several additional crossing areas. Lastly, Sharon’s 421st Armored Brigade, which was led by Colonel Haim Erez, was to trail Matt’s paratroopers to reinforce their bridgehead and destroy any SAM sites encountered.

At 5 pm on October 15, Israeli artillery opened up on the entire Egyptian line so as not to give away the real point of the Israeli attack. Raviv began his feint against “Missouri” and managed to penetrate the Egyptian defenses, inflicting multiple casualities but losing four tanks in the process. An hour later, Reshef ordered Lt. Col. Yova Brom, in charge of Sharon’s divisional reconnaissance battalion, to move out along with his three tank battalions and Matt’s paratroopers. Back at his headquarters, Elazar was notified that the Israeli offensive had commenced.

After emerging onto the Lexicon Road five miles south of Tirtur Road, Reshef was only five miles from the Chinese Farm where, unbeknown to him, Brig. Gen. Fouad Aziz Ghali’s Egyptian 16th Infantry Division and Brig. Gen. Ibrahim Oraby’s 21st Armored Division, which had taken quite a beating in the attack into the Sinai on October 14, had taken position. The former formation had 20 of its original 124 tanks, while the latter could field only 40 tanks. Reshef’s command was heading for the Chinese Farm and an enemy who outnumbered him two to one in tanks and had hundreds of infantry armed with Saggers and RPGs fighting from the cover of numerous irrigation ditches that dotted the area.

After crossing the intersection of the Tirtur and Lexicon Roads four miles behind the Egyptian front lines, Reshef penetrated the enemy position and opened fire. He hoped that a sudden appearance in their rear would stampede the enemy; if not, it would be a bloody affair.

Before reaching the intersection, Brom’s recon unit peeled off to the west, reached the canal, and took position along a two-mile stretch of the waterway without encountering any opposition. Meanwhile, Lt. Col. Amram Mitzna’s 40th Armored Battalion, along with Reshef’s mobile command post, passed through the Tirtur-Lexicon intersection without drawing any enemy fire. The same cannot be said of Colonel Avraha Almog’s 18th Tank Battalion, which lost 11 tanks at the crossroads to enemy tank shells, RPGs, and mines. As bad as Almog’s losses were, they paled in comparison to the unit following him; Major Shaya Beitel’s 7th Armored Battalion lost almost all its armored vehicles as it approached the intersection.

Although reduced in strength by half, the remainder of Reshef’s brigade struck the enemy’s rear, which turned out to be the administrative and logistical area of the 16th Egyptian Infantry Division. Soon Mitzna’s tank crews were firing at the plentiful targets they found in every direction with their cannons and machine guns, while his tank commanders engaged enemy troops with Uzis and hand grenades. Enemy ammunition stocks and thin-skinned vehicles were run over by Israeli tanks during the wild nighttime encounter.

Recovering from their initial surprise, Egyptian tankers and infantry were soon challenging the intruders in the dark. As the Israelis moved beyond the Egyptian encampment, Egyptian tanks from the nearby 21st Tank Division counterattacked. Although this effort was finally repulsed, the tank Mitzna was riding in was destroyed and the colonel wounded.

As Mitzna lay injured, Almog led four of his tanks east into the heart of the Chinese Farm, spraying the irrigation ditches full of Egyptian soldiers with machine-gun fire, tossing hand grenades, and torching ammunition and a radar station, while cutting down scores of enemy infantry armed with RPGs. Soon Almog, who was reinforced with six more tanks, fended off Egyptian armor coming from the north and east firing at ranges of less than 400 yards.

Reshef, his command scattered over several miles and reporting heavy casualties, halted on the Lexicon Road among Almog’s force. He ordered his supporting infantry down from their halftracks to help retrieve the wounded. He then radioed Brom to send back a company to reinforce what was left of Mitzna’s battalion.

Even as the brigade leader was directing his battle by radio, he had to fight off attacking enemy infantry, which had appeared out of the darkness. Using their tank and Uzi machine guns, he and his tank crews held their ground. The question was how long could his two battalions, which were holding separate fire bases deep inside the Egyptian Second Army’s bridgehead, hold out against repeated but uncoordinated enemy armor and infantry attacks.

Among scenes of Egyptian soldiers fighting and some fleeing in the glow of burning vehicles, four Egyptian tanks lumbered out of the night heading directly for Reshef’s tank. Ordering his gunner to fire as fast as possible, all four enemy vehicles were destroyed. Reshef then learned from a radio message from Sharon that the enemy tanks that had just attacked him were part of the Egyptian 14th Armored Brigade, 21st Armored Division, and that the former’s commander had been recently killed. Sharon also informed his subordinate that his efforts were being rewarded since intercepted radio traffic indicated they thought that Reshef’s attack was part of a plan to roll up the 16th Infantry Division’s flank northward and not a prelude to an Israeli crossing of the canal.

As the night of October 15 dragged on, the Israelis became more concerned with the situation on the Tirtur Road. Held by a brigade of enemy infantry heavily armed with antitank weaponry, the bottleneck along the road was blocking the route the roller-bridge was to travel to the canal. To help pry the road open, Reshef ordered Brom to clear the obstruction. The young reconnaissance leader led two of his companies in a 3 am attack on October 16. The Israelis knocked out three enemy tanks, but the effort came to an abrupt halt after Brom, who had discovered the seam between the Egyptian Second Army and Third Army six days before, was killed in his tank by RPG fire 30 yards from the intersection of the Tirtur-Lexicon Roads.

Determined to take the Tirtur Road and intersection, Reshef threw into the fight a reserve unit of paratroopers attached to his command led by Major Natan Shunari. Along with two tanks under Captain Gideon Giladi, the paratroopers riding in half-tracks crossed the Tirtur-Lexicon intersection but were immediately hit by small arms and RPG fire, destroying the tanks and the half-tracks. Under a continuing hail of enemy fire, the paratroopers retreated to the south. Of the 70 men Shunari led into the fight, 24 were killed and 16 were wounded.

A thick fog wrapped the Chinese Farm at dawn on October 16, and silence reigned there after 10 hours of savage combat. Hundreds of gutted and smoking vehicles littered the desert floor alongside scores of dead Egyptians and Israelis. The new day saw the Tirtur Road still blocked, the Akavish route too dangerous to use, and the Egyptians stubbornly clinging to the Chinese Farm. Reshef had lost 56 of his 97 tanks and would ultimately suffer 128 killed and 62 wounded at the Chinese Farm. By any standard the attack had been a failure, but the colonel was determined to continue the fight. He reasoned that if he was hurting so were the Egyptians.

At 5:30 am, Reshef contacted Sharon and told him that he would continue fighting even though his men were exhausted. Reshef said that artillery fire he had requested after Brom’s failed attack appeared to have had no apparent effect on the enemy infantry. This was because the Egyptian infantry was well protected in its deep ditches. Egyptian tanks were well hidden behind earthen mounds. Sharon said he would send one battalion from each from his other brigades to reinforce Reshef.

At dawn Reshef ordered the remnants of Mitzna’s and Almog’s units, which were down to 10 tanks from an initial strength of 43 tanks, to withdraw from their exposed positions on the plain and take positions on a high dune closer to the canal.

As Mitzna’s and Almog’s wrecked commands fell back, dodging Egyptian tanks and jeeps toting Saggers along the highways near the Chinese Farm, the Israelis again attacked the crossroads with a company under Major Gabriel Vardi. Taking cover behind knocked-out Israeli tanks, Vardi’s armor destroyed eight enemy armored fighting vehicles without any losses.

As Vardi dueled with the Egyptians, Reshef led the remainder of his reconnaissance battalion past the major’s command directly against the crossroads. This time the defenders raised white flags to surrender. The battle for the Tirtur-Lexicon intersection was over, but the struggle for the rest of the Tirtur Road and the Chinese Farm was far from over.

Lieutenant Colonel Ami Morag’s battalion, Sharon’s division, and a battalion from Raviv’s brigade arrived early in the morning two miles northwest of the Chinese Farm along the Tirtur Road. Morag had no idea of the fierce battle that had been raging in the area. The Egyptians unleashed a storm of Sagger missiles at Morag’s battalion, and he ordered his tanks to withdraw.

Morag tried to advance once more with eight tanks, which were covered by five others sheltering in a quarry. He led his small force in a rapid charge down the road. While the tank crews fired their guns, the commanders fired Uzis and threw grenades at the stunned Egyptian infantry lining the ditches on either side of the thoroughfare. Amazingly, Morag’s little band managed to reach the Tirtur-Lexicon intersection with the loss of only one of its vehicles. Seeing too many enemy infantry to handle, he led his men back down the Tirtur Road after picking up 20 paratroopers, survivors of Shunari’s unit. Unfortunately for the Israelis, the Tirtur Road was still blocked, and the Akavish route was still too dangerous to use.

As the hours passed on October 16, it was apparent to the Israelis that until the Tirtur Road was open the roller-bridge could not reach the canal. Equally important, until the Akavish Road was secured the pontoon bridge moving along it to the canal could not be used. Adan was given responsibility to solve this dilemma. He realized only friendly infantry could pry the enemy from the needed roads. He therefore requested that Colonel Yitzhak Mordecai’s 890th Battalion, which was part of Colonel Uzi Yairi’s 35th Paratroop Brigade, be assigned to him to finally secure the vital roadways. Yairi met with Adan at 10 pm on October 16 and was told that the assignment had to be accomplished before dawn on October 17. No aerial photos of the Egyptian positions were available, and no artillery preparation would be provided. The paratroopers would have to capture their objectives before morning, Adan insisted, because no foot soldiers moving across the terrain in daylight had a chance.

The paratroopers began to move shortly after midnight. Their route would be the same as that taken by Morag, although no one in Adan’s command knew about the masses of enemy infantry Morag had encountered. This was because Morag was in Sharon’s division, and his reports of his earlier movements were never given to Adan’s command.

The first contact the paratroopers made with the enemy was at 2:45 am, and it proved a disaster. One company wandered straight into the front of the Egyptian position, while a second, ordered to make a flanking attack, was likewise caught in the open by enemy infantry, tanks, and artillery, and its commanding officer was killed in the fighting. Meanwhile, the lead companies were shot up within 200 yards of the Egyptian lines, losing most of their officers killed or wounded. Soon enemy tanks approached, and they were only driven back by the paratroopers after Mordecai’s men were able to employ light antitank missile launchers, which set one Egyptian tank ablaze.

At dawn a tank battalion under future Israeli Prime Minister Lt. Col. Ehud Barak arrived to help the beleaguered paratroopers. Five of Barak’s tanks were immediately destroyed by Sagger missile fire, causing the remaining two vehicles to withdraw.

As Yairi’s men fought and died on the Tirtur Road, Adan, realizing that Egyptian attention was fixed on the contest there, was able to move the Israeli pontoon bridge down the Akavish Road and onto the canal. Although the paratroopers lost 41 dead and 100 wounded, their brave fight had loosened the Egyptian grip on the Akavish Road and opened the way to Africa.

On October 17, the Egyptians finally attempted to close the Israeli corridor to the canal and cut off all the enemy forces between the Lexicon Road and the canal. Guessing their opponent’s latest intentions, Adan and Sharon concentrated three armored brigades in the north against the Egyptian 16th Infantry Division and 21st Armored Division, while Lt. Col. Amir Jaffe’s tank battalion, with only 15 tanks, held the line west of the Chinese Farm.

During the night of October 16, Jaffe reported the apparent withdrawal of enemy infantry from the Chinese Farm. He was ordered not to interfere with that movement. The following day began with an attack by Egyptian infantry firing Saggers at Jaffe’s tank battalion. One of Jaffe’s tanks was able to disperse the attackers with a single volley. Shortly thereafter, the Egyptian 21st Tank Division struck Jaffe’s battalion. Jaffe commenced firing at his attackers at a range of 1,500 yards. Within half an hour the Egyptian tank crews pulled back, leaving 48 of their tanks burning on the battlefield. Jaffe did not have any tanks damaged in the one-sided encounter.

As the Egyptian tanks succumbed to Jaffe’s deadly fire, Adan on the same day destroyed the enemy’s 25th Armored Brigade attached to the Third Army, finally clearing the Tirtur and Akavish Roads. Meanwhile, Reshef’s command had been reorganized and reinforced. This enabled it to advance and secure the Chinese Farm. After bitter fighting, the position fell to the Israelis on October 18. Subsequently, the Israelis crossed to the west bank of the canal and cut off the Third Egyptian Army.

The fight for the Chinese Farm served the Egyptian purpose of causing the IDF unsustainable military losses, while for the Israelis it paved the way for their crossing of the Suez Canal. Both events were key factors in bringing the war to a close by cease-fire on October 25.

One of the more intriguing aspects of this battle was the “rolling bridge” the Israelis built and towed across the Sinai. The used it to cross the Suez on 19 October. This is the “Subsequently, the Israelis crossed to the west bank of the canal and cut off the Third Egyptian Army.” The bridge was so large it required some 10 tanks to tow it.

The best account of this I have seen is in the book “The Glory,” by Herman Wouk.