By Louis Ciotola

On March 14, 1590, King Henry IV of France achieved his greatest military victory on the field of Ivry. There was nothing ambiguous about the battle. Superior tactics won the day for the Royalists, who smashed through the ranks of their Catholic League enemy and utterly routed it. But while the dramatic outcome of Ivry was unquestionable, its significance was virtually nil. Ivry may have been one the most climactic moments of the last of France’s religious civil wars, but it was far from decisive. Instead, it was merely part of a ballet known to history as the War of the Three Henrys in which politics largely dictated the nature of military campaigns. Political reality along with Henry IV’s inability to exploit his martial masterpiece crippled the usefulness of the triumph. That did not, however, prevent the Battle of Ivry from becoming French legend.

Henry IV was a French Protestant, also known as a Huguenot. Henry was raised a Huguenot through the strenuous efforts of his mother, Queen Jeanne d’Albert, while his father, Antoine de Bourbon, willingly discarded his own Calvinist faith out of pure opportunism. Antoine was the King of Navarre and essentially a king without a kingdom, as Navarre had long been occupied by Spain. He consequently converted to Catholicism in order to possess some political relevance. Henry’s mother, estranged from her husband, ensured that her son did not follow the dishonorable path of his father. Antoine was killed in 1562 during the siege of Rouen at the start of the many religious conflicts that would internally disrupt French society for the better part of half a century. Ten years later, in 1572, Jeanne too died, leaving Henry both King of Navarre and a seemingly devout Protestant.

Before she died, Jeanne arranged for Henry to be married into the House of Valois, the reigning dynasty of France. The bride to be, Marguerite de Valois, was a Catholic, the sister of King Charles IX, and daughter of the supremely influential Queen Mother, Catherine de Medici. It was Catherine’s hope that the marriage of her daughter to a Huguenot prince would help foster peace in war-torn France. It was thus difficult for anyone to miss the black irony of what occurred only days after the wedding.

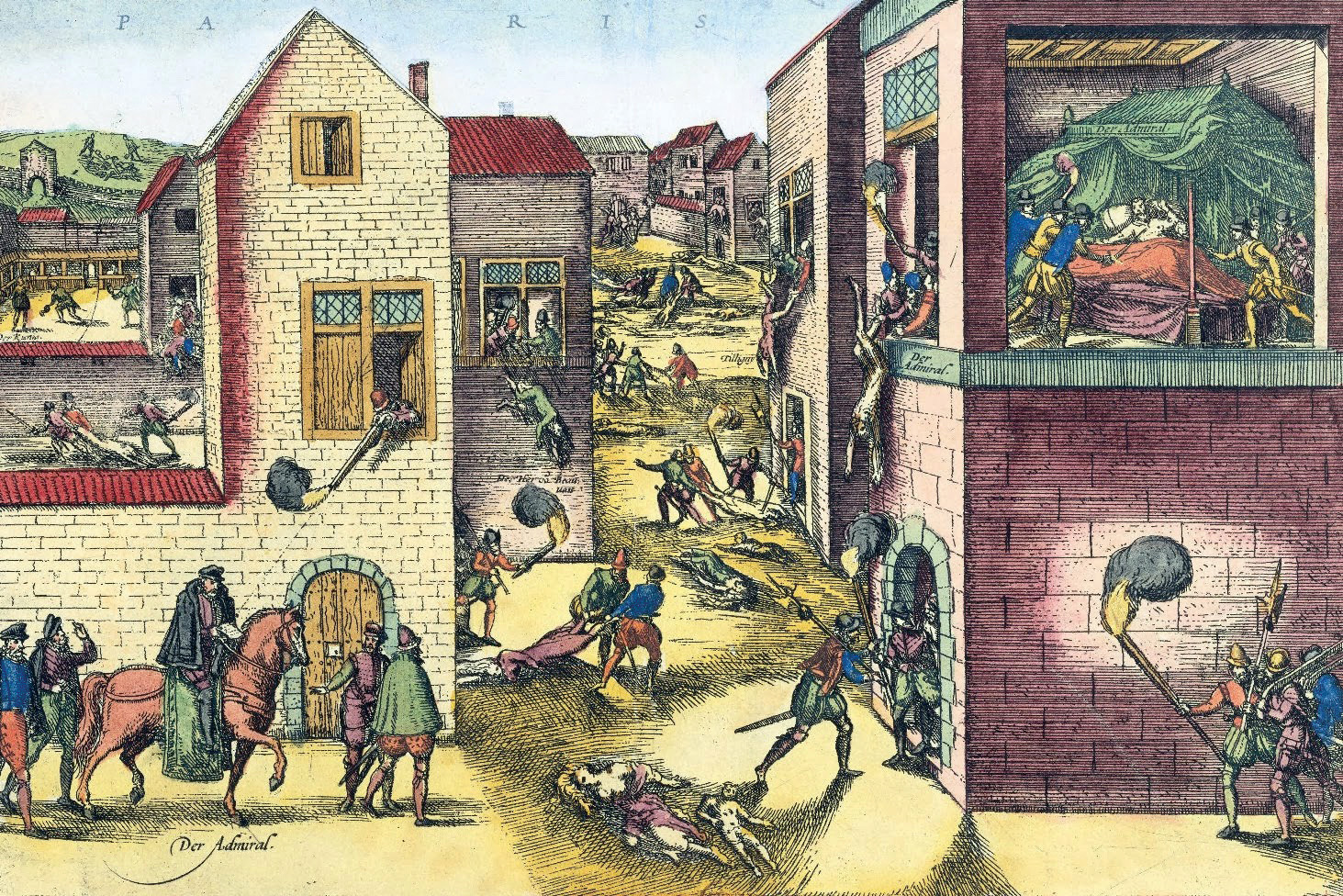

On August 22, 1572, the day following the wedding festivities, an assassin made a failed attempt on the life of the Huguenot leader, Admiral Gaspard de Coligny. It was largely believed to be the work of the Catholic Guise family, which collectively controlled large parts of northern and eastern France. Desperate to avoid possible retaliation and civil war, Catherine and Charles chose to preempt the Huguenots with an attack of their own. The result was the excessively bloody St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. Beginning in Paris but soon spreading throughout France, angry Catholic mobs brutally slaughtered tens of thousands of Protestants.

The indiscriminate murder of Protestants had not been the intention of the Valois. Only their leadership was officially targeted. As such, 18-year-old Henry de Navarre was in danger of losing his life. He only escaped execution by accepting conversion to Catholicism, a humiliation he had little recourse but to suffer. For the next three years he remained a virtual prisoner in Paris until making his escape in February 1576. Immediately thereafter denouncing his imposed faith, Henry, along with Huguenots throughout France, pledged themselves enemies not of the crown, but of the true instigator of the massacre, the House of Guise.

By the time of Henry’s flight from Paris, France had a new king in the person of Charles’ brother, Henry III. Henry III was largely conciliatory toward the resurgent Huguenots, earning him the contempt of many Catholics. Not least among the disgruntled were the Guises, who already had their own personal feud with the monarch and, like most in France, regarded him as corrupt, weak, and effeminate. As a consequence, in 1576 Henry de Guise formed the Catholic League, a group of Catholic organizations united as much to counter Huguenot power as challenge Henry III’s authority. Naturally, the move escalated tensions between Henry III and the Guises, especially when the king attempted to control their creation.

After 1576 the situation remained largely static, interrupted only by a few incidents of relatively minor warfare, until the death of Francis d’Anjou, the king’s brother and heir in June 1584. Because of his marriage to the king’s sister, the Huguenot Henry de Navarre found himself the new heir to the throne of Catholic France. For many Catholics, including the League and the Guises, such a development was entirely unacceptable but could at least be made more tolerable should Henry volunteer to convert. Henry, however, could not risk alienating his already wary Huguenot allies in exchange for winning over an uncertain number of Catholic loyalists. Ironically, the situation was not necessarily unwelcome to the Guises as they had been looking for some time to assert their self-assumed role as the defenders of France against heresy.

Contrary to Henry III’s demands, Henry de Guise began militarizing those parts of the League that he controlled, vowing to resist “those who are seeking to subvert the Catholic religion and the entire state.” As the king had feared, anarchy descended as Catholic elements within France took matters into their own hands under the excuse that Henry III had failed to act decisively against the Huguenot menace. League cells, many with no connection to the Guises, organized throughout the country, including a faction known as “The Sixteen” in Paris, named for the 16 sections of the city. There was little the king could do. Resisting the League would be tantamount to siding with heresy.

Things only got worse for the kings of France and Navarre. In January 1585, Henry de Guise completed the Treaty of Joinville with Spain, uniting them in a military alliance. That July, he forced Henry III to sign the Treaty of Nemours, whereby Protestantism was forbidden and Charles, the Cardinal de Bourbon, was designated as the rightful heir to the throne. Even more insulting, the French king would be forced to finance the League army, which was being used as the very leverage against him now that it had occupied much of northern France and recruited a large contingent of foreign mercenaries. But perhaps the greatest insult came from Pope Sixtus V who, by issuing a decree of excommunication against Henry, had interfered with issues of the crown and demonstrated just how powerless the king had become.

Henry could do little but declare war on the League, which he did in the name of France. He stated no equivalent hostility toward Henry III, dubbing the Treaty of Nemours “a peace with foreigners at the expense of the princes of the blood,” but immediately scrambled for aid from Europe’s Protestant powers so that he could maintain an army in the field that would likely come to blows with royal troops. The War of the Three Henry’s, France’s last religious war, had begun.

Henry’s choice of military strategy in 1585 was based on political and financial reality. He did not wish to war against the king, only the League, so indirect fighting would be the best way to draw out the hostilities while working to create a rift between the Royalists and the Leaguers. As he dispatched letter upon letter to Henry III stressing the evils of the League and even challenging Guise to a duel, he conducted a guerrilla-style campaign in Guyenne and Poitou, tempting the enemy to sap its strength against well-prepared fortifications. At any rate, the Huguenot forces lacked the financial capacity for offensive war. Moreover, their leadership and loyalties were questionable. Command was often divided between Henry and the Prince de Conde, at times nearly leading to disaster. Even Henry’s own wife was quick to abandon him, though that did not come to him as a shock or a disappointment.

If Huguenot difficulties were large, they paled in comparison to that of their adversaries. Henry III and Guise were as far from close allies as was possible. The king believed he could subvert the Treaty of Nemours and hoped Henry would eventually convert to undermine the despised League. In the meantime, he made every effort to keep Royalist troops out of Guise’s hands and even ordered his generals Jacques de Goyon, Lord of Matignon, and Anne de Joyeuse to avoid engaging Huguenot armies whenever possible.

For Henry III, the best case scenario would have been a battlefield demise of Henry de Guise, something he actively wished for. Guise had made great efforts to undercut the king’s military power. He removed Royalist officers from the royal army wherever possible, placing the troops under himself or his brother, Charles de Mayenne. He also levied large numbers of German and Swiss mercenaries to consolidate League domination of the north and east. Try as he did to counteract these measures, Henry III’s soldiers were, as a Tuscan ambassador recalled, “undisciplined, licentious, disaffected, and badly paid.” Like the Huguenots, the Catholics were in no condition to do more than engage in minor operations.

Huguenot deficiencies as a result of financial constraint were most evident in their inferior equipment, which was only tempered to some degree by tactical innovation. Like all French armies of the period, the Huguenots designed their cavalry to be the decisive arm in battle. Henry divided his cavalry between mounted carabins (arquebusiers), chevaux-legers (light cavalry), and gendarmes (heavy cavalry). He used the carabins as support troops that were also trained as infantry. They constituted the bulk of the cavalry. His light cavalry, faster and lighter than traditional cuirassiers, could also fight on foot.

The gendarmes were the most important branch of the cavalry and best demonstrated Huguenot innovation. Under the direction of Francois de La Noue, the Huguenots redesigned heavy cavalry tactics to suit their particular needs. Grouped together in deep formations of 300-600 men, the gendarmes were armed with wheelock pistols and swords in place of the cumbersome and expensive lance. Acting like German Reiters, they would charge forward and unleash a volley of shot into the enemy ranks. Unlike the Reiters, they would follow the volley with a headlong sword charge rather than turn back to reload in a caracole maneuver.

For the first two years of active fighting, Henry had little opportunity to test the new tactics in battle. That changed in late 1587 when he arranged a merger with recently hired Swiss and German mercenaries. Fearful of this dramatic boost in Huguenot power, Henry III finally ordered Joyeuse and Matignon to prosecute the war with more vigor and prevent the merger. Meanwhile, Henry had decided to march from southern France toward the Loire to facilitate the unification. Marching south separately, the two Royalist commanders planned to trap him in a pincer, with both ordered to refrain from battle until the other had arrived. Sensing the scheme, Henry maneuvered to avoid the trap while hoping to catch one of the two generals alone, confident that he could then achieve a victory.

At Coutras, on October 20, 1587, he succeeded in tempting Joyeuse to battle. Outnumbering Henry’s 6,300 men by nearly 4,000, Joyeuse was not about to refuse, regardless of his orders. But Henry was able to choose his ground and bait Joyeuse to attack in what was a long advance that tired and disordered the Royalist lines. When the moment appeared ripe, Henry, wearing his famous helmet plumed by white feathers, launched a ferocious countercharge with his gendarmes. Within five minutes the Royalist army was devastated. Joyeuse, who before the battle had claimed, “The King of Navarre is frightened,” lay dead, killed while trying to surrender as revenge for a previous massacre. Alongside him were 2,500 of his men. Huguenot losses were negligible by comparison.

After scolding Henry for his typical personal recklessness in battle, his commanders begged him to press his advantage. Afraid of pushing the king closer to Guise, he refused. Instead, as legend had it, he took a detour to present the captured Royalist standards to his mistress. True or not, his acute lack of funds prevented an offensive anyway, as the petty nobility within his army needed to withdraw and reequip their men, most of whom had yet to be paid. Consequently, Henry’s victory, the first major triumph of Huguenot arms, came to nothing.

Soon that would be the least of his troubles. While the Royalists fumbled with the Huguenots, Guise took it upon himself to meet the foreign threat. The king could not be more pleased. With any luck his Royalist armies would defeat Henry while at the same time Guise, fighting the Swiss and Germans, would be killed or humiliated. At the very least he would be far from Paris. Henry III subsequently gave the League no support and even tried to withhold supplies, but Guise was more than capable of procuring what he needed on his own. In two successive battles, Vimory and Auneau, he bested the mercenaries and prevented any chance of Huguenot reinforcement from the east. With those defeats and the death of Conde shortly thereafter, Henry was at his lowest.

As it turned out, the Huguenot cause was far from lost. The Guise victories, rather than unite Catholic France, tore apart the tenuous League-Royalist alliance. Just as Guise was about to finish off the mercenaries, Henry III negotiated with them, paid them to quit France, and took all the credit when they did so, undercutting his ally’s glory. Naturally, Guise was infuriated, and this came at a time when his popularity in Paris was soaring. Afraid of what might occur, the king forbade him from entering the capital and threatened to crush “The Sixteen.” It proved a momentous error in judgment.

Under the gun, “The Sixteen” turned to Guise for help. Encouraged by the Spanish and his own anger, he was only too willing to oblige. On May 8, 1588, Guise entered Paris. Four days later, when an understandably nervous Henry III rushed troops into the city to quash the League presence, all of Paris erupted in a popular rebellion forever known as the Day of the Barricades. The king’s gamble backfired completely as the population overwhelmed his troops and, after a brief stint as a prisoner in the Louvre, he fled as a refugee.

The king’s humiliation was not yet complete. Despite the petitions of the radical Catholic tide in Paris, Guise rejected any royal ambitions of his own, but he was not quite finished with Henry III. That July he forced the king to sign the Edict of Union in which all League demands were met in full and Guise was made lieutenant general of the royal army. Henry begged the king to unite with him against the treacherous League, but Henry III, ever the weakling and on the advice of his mother, instead bowed to Guise.

It was an unsustainable situation, and it became increasingly clear that France was not big enough for both Henry III and Henry de Guise. In the waning months of 1588, the king finally reached his breaking point. Rumors, which were entirely untrue, abounded that Guise planned his overthrow. With nothing left to lose, he decided he would rid himself of the menace once and for all. Meanwhile, Guise’s supporters kept him fully informed of the king’s machinations but, flush with power, Guise brushed off warnings of assassination quipping, “He would never dare.”

For reasons quite understandable, Guise had fatally underestimated the feckless monarch. On December 23, a bodyguard dispatched by Henry III murdered him as he arrived for an appointment with the king. The next day his brother Louis, Cardinal de Guise, followed him to the grave. Pleased with his actions and surprising display of backbone, Henry III rushed to his now decrepit mother to tell her the good news. Her reaction was unsettling. “What do you think you have done?” she asked, “You have killed two men who have left a lot of friends.”

Catherine’s last admonition to her son (she would be dead within two days) proved painfully prophetic. Enraged by the murders, Paris exploded in rioting. Rather than regain Catholic supremacy, the king’s support fell lower than ever as League cells seized control of city after city. Guise’s brother Mayenne simply stepped in to fill his dead sibling’s role as lieutenant general, and the king was even excommunicated by the pope. Far from being disheartened, League power was as robust as ever. With his mother now dead and support all but withered, Henry III at last turned to the one man who could save his crown, Henry of Navarre.

Conciliation was the best Henry III could do given the situation while Henry, who had already been taking advantage of the turmoil in Paris to launch an offensive, continued to profess loyalty to the crown. On April 3, 1589, the Huguenots and Royalists agreed to an alliance against the League. The agreement provided an immediate boost to Henry’s forces, especially the acquisition of the Royalist Swiss pikemen, as his infantry had been sorely deficient. Reinforced, his offensive toward Paris picked up steam. A series of skirmishes, most notably at Tours, drove Mayenne back to the capital and strengthened the trust between Huguenot and Royalist commanders. Said an English agent, “The King of Navarre is thought to do what he does by sorcery, for all places do yield to him.”

In July the two allies reached Paris hoping for a quick capture of the city that would rip out the heart of the League. In their initial attacks, the Royalists managed to seize a bridge at Saint-Cloud while the Huguenots penetrated into the suburbs at Meudon. It was then, as they considered how best to maintain momentum, that a young monk named Jacques Clement, claiming to have information on the defenders, gained an audience with the king in order to plunge a dagger into his abdomen. Approaching death, the king espoused Henry’s right to the succession and urged his followers to do the same. On August 2, he died. Henry of Navarre became Henry IV, first Bourbon king of France.

His predecessor’s dying endorsement provided no guarantee that Henry would be found universally acceptable as the legitimate king of France. Indeed, when he again refused to convert to Catholicism for fear that he would lose his base of support and foreign benefactors, many former Royalist Catholic nobility quit his newly acquired army, taking their men with them and consequently causing his force to shrink significantly. Although there were some notable exceptions who were satisfied by his pledge to defend the free practice of Catholicism, such as Armand de Gontaut, Marshal Biron, and Francois, Duc de Montpensier, enough left to make a continued siege of Paris impossible. Meanwhile, in the city itself Parisians cheered the Cardinal de Bourbon as the new King Charles X, an ironic gesture as the cardinal was a Royalist prisoner, one whom Mayenne was making no effort to liberate.

Henry’s total army was now a mere third of what it had been before the previous king’s death, reduced to 18,000 men. As for his foreign contingents, he was forced to bribe the Swiss captains to maintain the use of their pikemen, the bulk of whom were growing restless for lack of pay. Considering the substantial drop in strength, most of those who remained loyal to Henry advised him to withdraw south across the Loire, but he rejected the advice out of hand as detrimental to his now kingly status. He was already compelled to leave Paris. Falling back to the start could undermine what support he had left. Instead, he would lead the army north into Normandy, taking towns along the way, in an effort to procure supplies from England.

By contrast, Mayenne’s army was growing as he had managed to convince many League leaders to come to the defense of Paris. Even though a number of them were wary of risking their men in Mayenne’s hands, his army nevertheless greatly outnumbered the Royalists, having 20,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry, which were largely reinforcements from Flanders and Lorraine along with some Swiss and German landsknechts. Still, it was only with hesitancy that he decided to pursue the enemy north, pushed on by a threat to League-controlled Rouen.

But Henry never intended to target Rouen. His priority was English supplies and reinforcements, which could best be attained at the port of Dieppe. Mayenne’s approach, however, forced him to march inland from the port to establish a defense. He selected a small valley formed by two rivers near the town of Arques where, protected by hills, marsh, and forest, the Royalists would be at an advantage should the Leaguers attempt battle.

The Royalists further strengthened their position with the construction of two parallel trenches at their front. Biron, commanding Swiss and German as well as French troops, held the first trench while French soldiers and Henry’s Swiss Guard manned the second. Also in the first trench sat the cannons with the cavalry in between. Despite their preparations, many Royalist generals were uneasy with their numerical inferiority, but Henry was unfazed noting, “You are not counting everything. You have left out God and the cause of right which is on my side.” Mayenne was equally apprehensive, hesitating for three full days in the vain hope that his enemy would withdraw. His indecisiveness gave Henry more time to prepare.

Although skirmishing began on September 14, the battle proper commenced on September 21 when Mayenne’s Germans ventured a flanking attack through the woods against the Royalist right that succeeded in driving Biron out of the first trench. Some 300 Leaguer landsknechts even managed to penetrate completely behind the Royalist lines by feigning surrender only to unleash temporary chaos at the first opportune moment. Henry would later hang a number of Swiss pikemen who had fled the first trench without fighting, ignoring their explanation of a lack of pay.

The heaviest combat took place at the second trench where the Swiss held firm supported by a Royalist countercharge led by Henry himself. The fighting was thick, and at least once the king found himself surrounded and crying out for anyone with “courage enough to die with their prince,” before being rescued by his gendarmes. The tide at last began to swing in Henry’s favor at noon when, thanks to the lifting of the morning fog, the Royalist cannons could open fire. Shortly thereafter, the timely arrival of veteran troops under Francois de Coligny, son of the Coligny of St Bartholomew fame, turned events decisively in Henry’s favor.

The Battle of Arques left Henry free to continue his plans in Normandy. It provided a huge boost to morale and lured in a flood of new recruits, though the League army remained larger. Demoralized, Mayenne withdrew on October 6, struggling to keep his force intact in the face of mounting tensions with League nobility that pushed him ever deeper toward Spanish dependency.

Several days after the battle, the English reinforcements Henry has hoped for arrived in Dieppe at last. In combination with a second Royalist army under La Noue, the king was now sufficiently strong to again move on Paris. On November 1, he reached the capital and quickly learned that things would not be any easier the second time around. Although they had beaten the League army to the city, the Royalist attack penetrated only as far as Philippe-Auguste’s wall marking the border of the city proper due to stiff Parisian resistance, which increased even more following the massacre of 400 civilians at the abbey at St. Germain.

Worse still, the besiegers almost unbelievably allowed Mayenne to enter the city the following day across a bridge over the Oise that they had neglected to destroy. When subsequent efforts to tempt Mayenne into battle failed, it became clear that Paris could hold out indefinitely. Although many within the city had urged Mayenne to accept battle to ward off the growing influence of Spain, military prudence dictated otherwise. Mayenne’s patience paid off.

Henry’s decision to again abandon Paris was unpopular within the Royalist ranks. “I do what I can,” he humbly told them. Following a brief stint in Tours, he again marched north into Normandy fully expecting Mayenne to pursue. Here he fared much better, meeting success after success as he captured nearly every place of importance in the region save Rouen. After taking Lisieux he mockingly exclaimed, “I took the place without firing one of my cannons, except to make fun of them.” His luck continued at Meulan where, while observing the enemy from atop a church steeple, he survived a near miss with a cannonball that passed harmlessly through his legs.

With Spanish prompting and reinforcements from the Netherlands in the form of Spaniards and Walloons under Philip of Egmont, Mayenne commenced his pursuit as the Royalists conducted their latest siege at Dreux. Even after losing his English contingent as well as many troops to garrison duty, Henry was eager to do battle. On March 12, he raised the siege of Dreux and moved his 8,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry onto the plain of Saint Andre between the towns of Nonancourt and Ivry, only 36 miles from Paris. He was met by a League army with 15,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry. The two forces skirmished lightly throughout the day as they positioned themselves for an inevitable confrontation.

Although the plain of Saint Andre was soft and muddy, Henry would as always rely on his cavalry to win the day. He divided it into six segments, each flanked by infantry and covered by arquebusiers. The king planned to strike the enemy left with his right center and accordingly posted himself there in command of his best gendarme, a contingent of Swiss infantry, and his personal guard.

All of Henry’s commanders leading a segment of the army were former officers serving Henry III. To his right at the end of the line were German and French infantry under Dietrich of Schomberg. On the opposite end was Marshal Jean d’Aumont with 300 horse and two regiments of French infantry. Between d’Aumont and Henry from left to right were cavalry, Swiss pike, and landsknechts under Montpensier, 400 light horse and the five Royalist cannons under Charles, Duc d’Angouleme and Sieur de Givry, and Baron de Biron with some horse and a large number of infantry. The baron’s father, Marshal Biron, led the reserves, some 150 horse positioned behind the right flank.

Mayenne possessed little enthusiasm for battle, but his positioning with his back to the river Eure made it impossible to avoid. He drew up his army similarly to the Royalists, dividing his cavalry with the infantry, and took command of the left center exactly opposite Henry at the head of 700 lancers and 400 Spanish horse-arquebusiers. To his left was Charles, Duke of Aumale, with French horse and French and Walloon infantry. Charles Emmanuel, Duke of Nemours, led the far right composed of light and heavy cavalry with Swiss and landsknechts. Between Nemours and Mayenne was Egmont with French lancers and Walloon infantry followed by German Reiters backed by more Swiss and German foot. The guns sat to the right of Nemours.

As the League line extended farther than the Royalists’, Mayenne planned to outflank the enemy on both ends. But there were a number of flaws in his formation, particularly the close proximity of his units, which would restrict his Reiters’ caracole. Henry, by contrast, would suffer no such difficulties as he ordered his cavalry to dispense with the maneuver altogether.

The moments just before battle were filled with rhetoric meant to spur common soldiers that was typical of the era. Flying his banner bearing the crosses of Lorraine that symbolized his dead Guise brothers, Mayenne petitioned his men to fight for the liberation of France from heresy. Henry, meanwhile, rallied his men in his typically personal way, exclaiming, “If you lose your ensigns, cornets, or banners rally round my white plumes for you will always find it on the road to victory and honor.” As noble as his words may have been, however, they were not always enough to drive men forward blindly. Only moments before, he felt compelled to apologize to a distraught Schomberg after having imprudently accused him of cowardice for having presented the issue of his men’s arrears in pay on the eve of battle. Fortunately for the Royalists, the ill-timed incident caused no serious discord.

The royalists struck first, opening up a cannonade with Egmont and the Reiters as their target. Two rounds into the bombardment the League cannons returned the favor against Montpensier. While the League guns wildly missed their target, Royalist cannonballs tore viciously into Egmont’s Walloons. The effectiveness of his enemy’s fire forced Mayenne’s hand. With the choice being between standing still and taking heavy casualties or fighting in an attempt to end the punishment, he chose to fight.

The bulk of the battle consisted of a series of cavalry charges and clashes all along the opposing lines. While Montpensier and Nemours fought to a standstill, elsewhere events were much more fluid. On the Royalist left, d’Aumont’s horse broke through the League lines, driving its light horse into the woods and absorbing a volley of arquebus fire upon penetration. On the opposite end of the line, Schomberg and Aumale met in a draw that was only decided in favor of the Royalists upon the arrival of Biron’s reserves. The Leaguers had better success in the center, where Egmont’s Walloons sliced through Angouleme and Givry, then turned on the Royalist cannon from the rear, knocking it out of commission. It proved a temporary victory as they were thoroughly disordered from the charge and subsequently driven off by Baron Biron’s carabins.

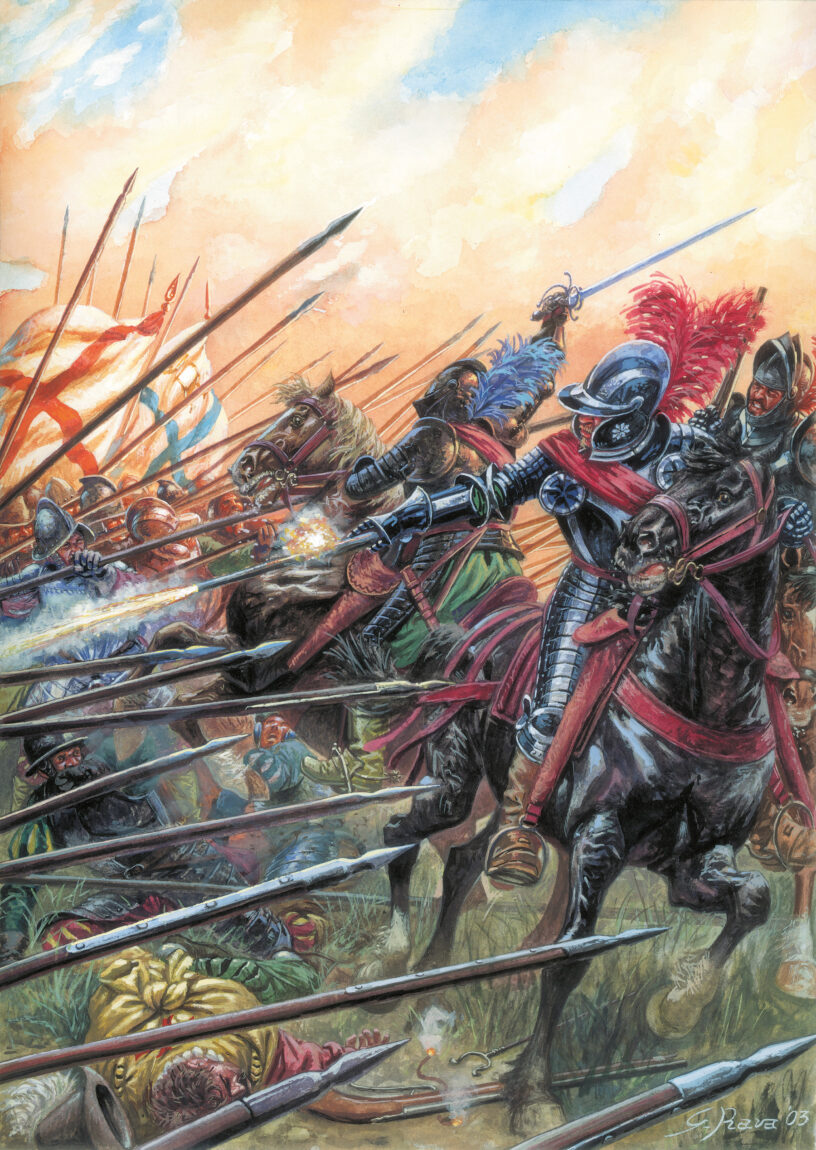

It was the clash between Henry and Mayenne, however, that decided the battle. Things began poorly for the Leaguers. Their Reiters’ attempt at a caracole was an unmitigated disaster as first it was disrupted by the still active Royalist guns and then, because of the compactness of the Leaguer lines, crashed into Mayenne’s main body, forcing it to halt its attack on Henry. The Spanish mounted arquebusiers fared better, causing a number of casualties including the king’s standard bearer, creating a brief fear that the king had fallen. But Henry was alive and well and ready to strike his fumbling enemy.

A witness later testified that Henry “was everywhere, as if he had a hundred eyes and as many arms.” With his gendarme in tow, he smashed headlong into Mayenne’s troops as they struggled vainly to recover their momentum. The Leaguer lance was made useless by its failure to charge so that the lancers were forced to discard them for swords, but it was already too late. After 15 minutes of sharp combat amid steel and shot, the Leaguers broke and attempted to flee. With a small body of men, Mayenne escaped across the Eure, then in an act of cold necessity destroyed the bridge over which he had passed, trapping many of his men on the opposite bank.

Henry, wounded several times and dazed by a blow to the helmet, ordered that any French captured be spared but all foreigners killed. As a result, the Royalists slaughtered the remaining landsknechts and Walloons almost to a man. Only the Swiss, thanks to a stout defense, saved their own lives by negotiation. Those Leaguers that eluded death or capture retreated to Ivry and Chartres.

“God has shown that he favors right more than power,” Henry bragged after the battle as he was presented with Mayenne’s captured standard. Indeed, the more powerful force suffered greatly at Ivry. Nearly 4,000 League soldiers remained dead on the field, including Egmont, who had been shot through the head as Biron decimated his Walloons. Thousands more were made prisoner. Royalist losses amounted to fewer than 500, though among them was the luckless Schomberg.

Henry’s victory at Ivry has long been stained by his failure to exploit it by marching directly on Paris. Even his enemies admitted the city would have surely fallen had he done so. Instead, the Royalist army did not reach Paris until May 6, and by then it was too late. Many of Henry’s detractors have called him lazy or branded him an overrated general. Some even accused him of wasting time so that he could hunt. His defenders posited poor weather, flooding, and the need for English reinforcements and supplies for his patience. Regardless, an immense opportunity to end the war was missed due to an overly cautious strategy.

The Parisians were fully prepared for their third siege in less than two years. The city garrison was led by Nemours this time rather than Mayenne, whose popularity had suffered immensely due to his defeats at Arques and Ivry. He waited at a distance as League preachers reviled against him almost as much as Henry. To the citizens of Paris, Henry was the epitome of evil waiting for his chance to take revenge upon the population with an unimaginable bloodletting. Their fanatical defense would reflect that belief.

Henry, meanwhile, desperately tried to portray the opposite image, which is the reason he did not press the siege as vigorously as possible. By August, the city was facing starvation on a mass scale as the Royalists prevented all grain supplies from entering. Said Francois d’Orleans, “The inhabitants of Paris are in such desperate straits that I believe they will be starved into submission within fifteen days.” Henry’s generals therefore condemned his decision to permit women and children to evacuate the city under safe conduct. Humanitarian as it was, it critically damaged the prospects of inducing surrender. Nevertheless, 13,000 Parisians would die of starvation and another 30,000 from disease.

League representatives did agree to negotiate, but it was simply a ploy to buy time. In September relief at last arrived in the form of a Spanish army under Alexander Farnese, the famous Duke of Parma. Parma, by far the most experienced soldier present, ignored Mayenne’s pleas and avoided Henry’s attempts to fight a pitched battle, choosing a more sophisticated strategy of maneuver, with which he successfully broke the siege through the occupation of Lagny. For Henry, his third siege of Paris, despite the glory of Ivry, was an unmitigated disaster. His army broke up as many of his supporting nobles returned home in disgust. Henry himself withdrew northwest.

Such was the story over the following three years as the king struggled to keep an army in the field. There was no more glory to be had. The continued intervention of Parma made life difficult while a failed siege of Rouen showed that Paris had not been a fluke. Even after Parma left for good in May 1592, Henry could make no military gains. It soon appeared that he had only one card left to play to maintain his tenuous hold on the throne.

By the start of 1593 it became apparent to Henry that his failures on the battlefield would cause whatever Catholic support he still retained to disintegrate. Meanwhile, at the prompting of Spain, the League called for a meeting of the Estates General for the purpose of selecting a legitimate king. When the body announced it would accept Henry as king in exchange for a conversion to Catholicism, he was given one last chance to obtain peacefully what he could not through war. At last he relented and in July 1593 was converted. “Paris is worth a mass,” he was reputed to comment. Many of his Huguenot supporters and foreign benefactors did not agree, most notably Elizabeth I of England, but the deed was done and with it the cause of his enemies. The League slowly deteriorated, and by the time of the Edict of Nantes in 1598, through which Henry granted the Huguenots full civil liberties, it was all but forgotten.

For a man who once said, “Religion is not something you discard like a shirt,” conversion for political reasons may have seemed hypocritical, especially in an age when the Inquisition actively hunted such men, but there was little doubt that it was best for France. By 1593 the country was exhausted from a half century of civil war, and many Catholics were still unprepared to relent against heresy. Furthermore, without his Catholic supporters Henry could not have continued on, let alone have issued the Edict of Nantes which, while not erasing his hypocrisy, went a long way toward tempering it.

Much more uncertain than Henry IV’s political legacy was his military legacy. Parma, the premier general of his age, once said of Henry, “He can make a splendid retreat, but why does he get into situations where such a retreat is necessary? I never do.” Even if Parma was an unfair standard of comparison, there was little doubt that Henry’s skills in military matters were limited, his financial pains notwithstanding. On the field of battle he relied exclusively on cavalry, showing little talent with infantry or artillery, while his sieges of major cities almost always ended in failure. Perhaps his only real talents were his charisma and ability to field an army at all.

Ivry was the sole exception. On an open plain without the aid of geography, Henry won a clearcut and skillful victory. Sadly, it became tainted by its failure to bear a decisive impact. Nevertheless, thanks in no small part to the contemporary propaganda, the Battle of Ivry became part of French lore. Despite all of his shortcomings, Henry IV still remains one of France’s most popular kings.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments