By William E. Welsh

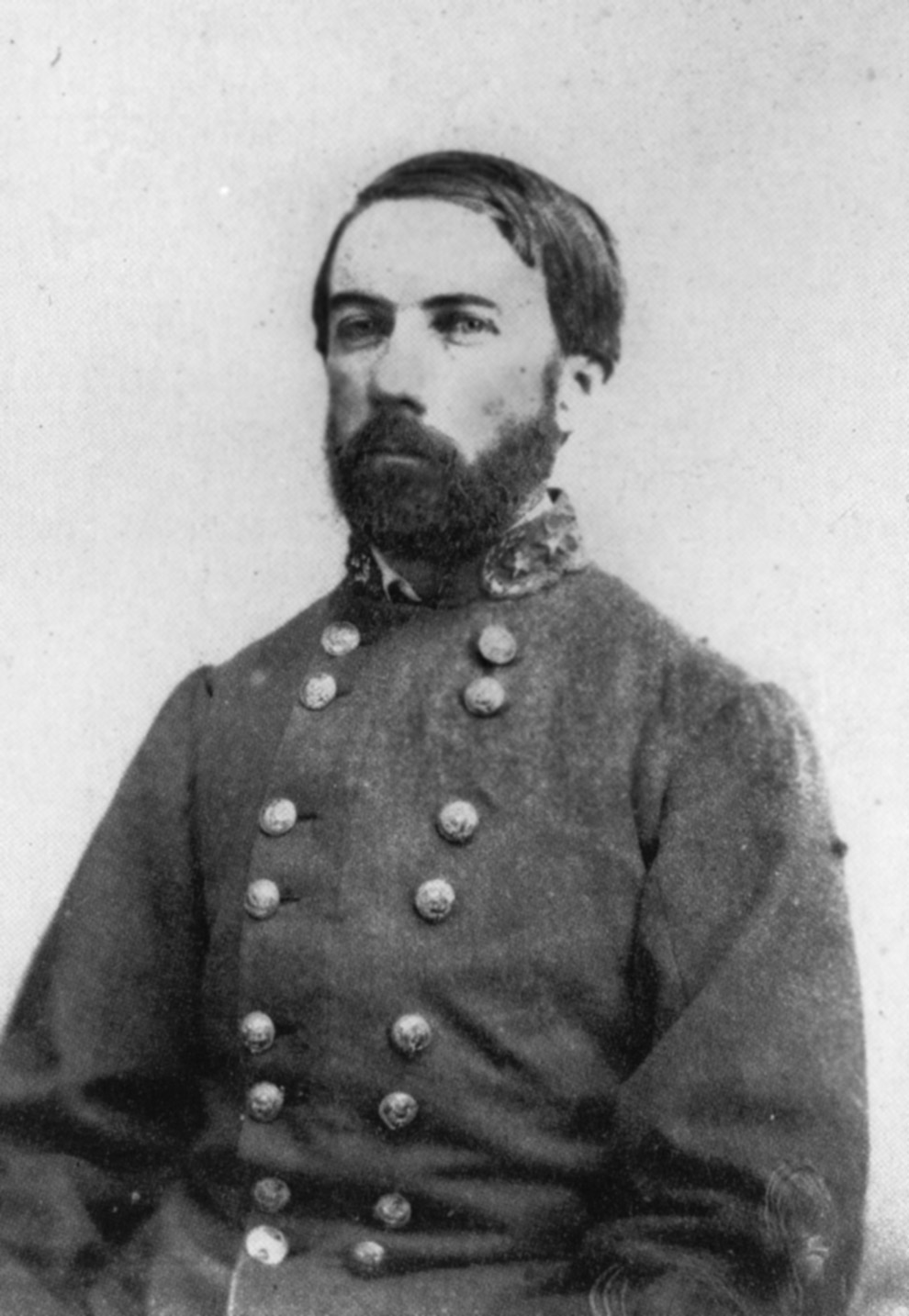

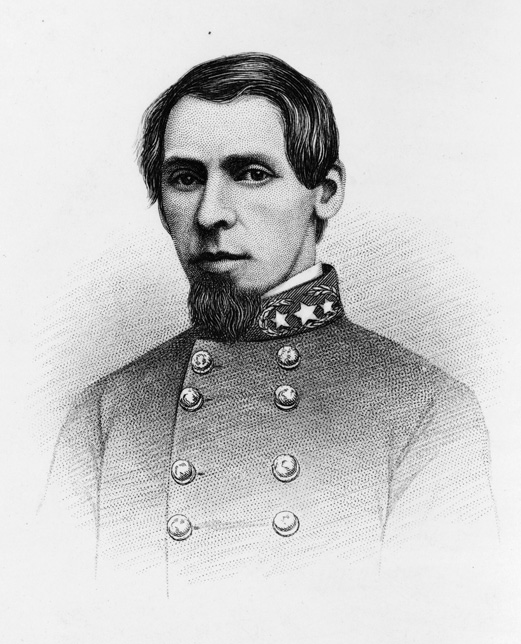

Two men rode forward from Sharpsburg, Maryland, on the morning of September 17, 1862. The one in front was of slight build with a scraggly beard, scrawny neck, sunken cheeks, and a high forehead. The second man was clearly not pleased that he had to accompany the two-star general in front of him. As if the danger posed by the Federal long-range guns from the east side of Antietam Creek was not bad enough, Yankee skirmishers a short distance to the north took aim at the two riders and tried to knock them from their saddles.

Major General Daniel Harvey Hill wanted a better view of the ground on which his brigades would be fighting that day, so he rode slowly to take in every detail of the rolling farmland. “We rode for a quarter mile along the fence, drawing the fire of the whole skirmish line as we rode in a slow walk,” wrote Major James W. Ratchford, Hill’s adjutant, who accompanied him on the reconnaissance. “During this ride three couriers started toward the general with messages, and each was shot down or had his horse shot from under him. I expected every moment that both of us would be killed, but we came through without a scratch.”

Hill “seemed not to count danger for himself or his staff when duty required it,” wrote Ratchford. “As we rode along, the constant fire from enemy sharpshooters did not in the least disturb his thorough examination of the enemy position.”

Hill had a reputation in General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia for exposing himself to danger. The North Carolinian was “positively the bravest man ever seen,” said Lt. Col. Moxley Sorrel, who was Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s adjutant. It was only one of the unique characteristics of a complicated man, whose behavior often confused those who served under him, as well as his fellow officers.

Hill was born on his family’s plantation in York District, South Carolina, on July 12, 1821. He was accepted into the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1838. Despite being short and thin and suffering from a chronic spinal condition, he successfully made it through the academy, graduating in 1842. A second lieutenant in the U.S. 4th Artillery, he served with distinction in the armies of Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott during the Mexican War.

Suffering daily from poor health, Harvey Hill resigned from the Army in 1848 to take a job as a mathematics professor at Washington College. He and his bride, Isabella Morrison, set up house at the college in Lexington, Virginia. After six years at Washington College, he transferred to Davidson College in Davidson, North Carolina, where he taught from 1854 to 1859. While the Hills were living in Lexington, Isabella introduced her younger sister, Mary Anna, to Thomas J. Jackson, a professor at Virginia Military Institute. When the two were wed in 1857, Jackson became Hill’s brother-in-law.

Hill left Davidson in 1859 to help found the North Carolina Military Institute in Charlotte, North Carolina. At the outbreak of the war, he was eager to join the Confederate army and reported to Raleigh. North Carolina Governor John Ellis gave Hill the rank of colonel on April 24, 1861, and asked him to assist in training recruits.

Hill’s many years in academia sharpened his intellect, but his debilitating spinal condition made him highly irritable and contributed substantially to his arrogance, sarcastic nature, and sharp tongue. These were characteristics that would hold him back during his future service to the Confederacy despite his strong leadership skills and indisputable courage under fire.

Hill and his regiment, the 1st North Carolina Volunteers, arrived in late May at the front lines in Yorktown, Virginia. Hill reported to Colonel John Magruder, the senior commander of a small force entrusted with keeping the Federals bottled up at Union-held Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula. On June 10, Hill and his regiment played a key role in the Battle of Big Bethel in which the Confederates easily repulsed piecemeal attacks by Federal forces under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler.

For his splendid direction of the main part of the battle, Hill was promoted to brigadier general on July 10. Hill and his regiment remained at Yorktown through July and did not participate in the Confederate victory at First Manassas.

Confederate General Joseph Johnston, the senior commander of Confederate forces in Virginia, promoted Hill to major general on March 26, 1862. When Maj. Gen. George McClellan transferred his 121,500-strong Army of the Potomac by water to the Virginia Peninsula in mid-March, Johnston began a slow retreat west toward the Richmond defenses. During the ensuing Peninsula Campaign, Hill’s division would play a prominent role in four battles: Williamsburg, Seven Pines, Gaines’ Mill, and Malvern Hill.

Of the four battles, Seven Pines was Hill’s best performance, exhibiting his initiative and skill at handling his brigades. The two-day battle began on May 31 when Johnston ordered three columns, one of which he entrusted to Hill, to attack the Federal III and IV Corps on the south side of the Chickahominy. Even though the other Confederate columns participating in the attack were not in place by midday, Hill received permission to begin the attack at 1 pm.

Hill’s objective was to capture the crossroads of Seven Pines. To do this, he would have to defeat Brig. Gen. Silas Casey’s Third Division of the Union IV Corps. Casey’s men were entrenched three quarters of a mile west of the crossroads of Seven Pines. Brig. Gen. Samuel Garland’s brigade spearheaded the attack. Hundreds of Rebels from Colonel George B. Anderson’s and Brig. Gen. Robert Rodes’ brigades advanced on Garland’s left and right, respectively. Garland’s men were caught in crossfire from converging Federal batteries and also had to endure heavy fire from Yankees protected by breastworks. A soldier in the 23rd North Carolina, one of Garland’s regiments, recalled the ordeal. “The balls were falling all around us thick as hale (sic) all the time,” wrote Private Leonidas Torrence. “It did not look like there was any chance for a man to go through them without being hit. I saw several trees nearly as thick round as my body cut down with cannon balls…. It was a very distressing place.”

Hill’s graybacks drove the Federals from their first line of entrenchments. Anderson’s line overlapped the Federal right, which allowed his men to enfilade Casey’s flank. On the Confederate right, Colonel John Gordon’s 6th Alabama of Rodes’s brigade captured an artillery redoubt. When Hill received reinforcements from Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, he pressed a fresh attack on Casey’s second line, but heavy rains and nightfall put an end to the fighting that day. The fighting the next day was inconclusive. Hill had performed superbly on the first day, setting the tone of the battle, ably controlling his brigades, and capturing a key enemy position.

During the fighting on the second day, Johnston was severely wounded. Confederate President Jefferson Davis replaced Johnston with General Robert E. Lee. After a long lull in the fighting, Lee launched an offensive against McClellan on June 25. Lee’s offensive was known as the Seven Days Battle. Hill’s division fought well at Gaines’ Mill and Malvern Hill during the offensive. During Lee’s offensive, McClellan lost his nerve and retreated to a strong position at Harrison’s Landing on the James River.

McClellan remained entrenched at Harrison’s Landing throughout August. In the meantime, Lee shifted the bulk of his forces north. Hill’s brother-in-law, Maj. Gen. Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson, defeated a Union army at Cedar Mountain on August 9. After that, Lee’s army defeated Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia at Second Manassas. While the Second Manassas campaign was under way, Hill served a month-long stint as commander of the Department of North Carolina, but Lee recalled him just before the pending Maryland invasion. Hill rejoined Lee’s army at Chantilly, Virginia, on September 2.

At a council of war on September 9 near Frederick, Maryland, Lee decided to divide his army to capture the 13,000-man Union garrison at Harpers Ferry before moving farther north. Lee detailed Jackson to capture the town while Longstreet and Hill waited at Boonsboro just west of South Mountain. When Lee received what later turned out to be an erroneous report of Union cavalry operating near Hagerstown, he ordered Longstreet north to disperse it. Lee ordered Hill to remain behind at Boonsboro with his five brigades to cover the roads leading out of Harpers Ferry to the north if the garrison tried to escape. As for the Army of the Potomac, which was moving toward Frederick, Stuart was to cover the gaps through South Mountain and keep Lee informed of McClellan’s progress.

After Pope’s disastrous defeat at Second Manassas, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln turned again to McClellan to defeat Lee. McClellan moved faster in pursuit of Lee than the Confederate commander had expected. Jackson had divided his army into three groups to capture Harpers Ferry, which left Lee’s army divided into five parts with the enemy rapidly advancing toward Turner’s Gap where the National Pike crossed South Mountain.

Lee directed Hill on September 13 to hold Turner’s Gap and informed him that Longstreet was marching to reinforce him. Harvey Hill rode shortly after daybreak on September 14 to survey the terrain. He found that Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart had ridden south to oversee the defense of Crampton’s Gap where Stuart mistakenly believed the main Federal thrust would be made because it was closer to Harpers Ferry.

Turner’s Gap “could only be held by a large force, and was wholly indefensible by a small one,” Hill later wrote. Although there was good defensive ground at Turner’s Gap, the position was vulnerable to being turned on both flanks. Hill not only had to hold Turner’s Gap but also cover Fox’s Gap three quarters of a mile to the south and Frosttown Gap a mile to the north. The ground Hill’s troops would defend was extremely rough with various hollows and knobs. It would give them a strong advantage on the defense.

Hill already had sent one of his five brigades, the one commanded by Brig. Gen. Alfred Colquitt, to Turner’s Gap the day before. To assist Hill, Stuart had posted 250 troopers of Colonel Thomas Rosser’s 5th Virginia Cavalry and a section of horse artillery under Captain John Pelham at Fox’s Gap. Torn between watching the roads leading away from Harpers Ferry and covering the gap, Hill vacillated on how many troops to bring to Turner’s Gap. The morning of his reconnaissance, Hill had ordered Garland’s brigade to march to Turner’s Gap to join Colquitt. This left the brigades of George B. Anderson, Rodes, and Brig. Gen. Roswell Ripley at Boonsboro to watch for any sign of Federals retreating north from Harpers Ferry.

Hill told Colquitt to pull his men back from the base of Turner’s Gap to its crest, and he sent Garland’s 1,100 men along a narrow road on the ridge to Fox’s Gap where the cavalry was posted. Hill also ordered Captain James Bondurant’s four-gun Jefferson Davis Artillery to follow Garland.

Major General Ambrose Burnside, commanding the right wing of McClellan’s army, planned to conduct a double envelopment of Turner’s Gap by sending the IX and I Corps against Hill’s right and left flanks, respectively. From his headquarters at the Mountain House in Turner’s Gap, Hill watched the long blue columns in Middletown Valley to the east that were slowly making their way toward the foot of the mountain. “It was a grand and glorious spectacle,” Hill wrote, “and it was impossible to look at it without admiration. I had never seen so tremendous an army before, and I did not see one like it afterward.”

Garland had to cover 1,300 yards at Fox’s Gap, which was too much for his brigade. So he placed the 13th and 20th North Carolina north of the Old Sharpsburg Road and the 5th, 12th, and 23rd North Carolina Regiments south of the road. This left a large gap between the two groups of Tarheels.

Brigadier General Jacob Cox’s Kanawha Division, which formed the vanguard of Maj. Gen. Jesse Reno’s Union IX Corps, made contact with Garland’s right wing at 9 am. Colonel George Crook’s brigade advanced on the left, and Colonel Eliakim Scammon’s brigade advanced on the right. Cox’s line overlapped Garland’s right. Smoke blanketed the woods with men on both sides scrambling for cover behind stone walls on the mountaintop. Garland called for his two regiments north of the Sharpsburg Road to come to the aid of the three already engaged.

The Federals soon overran Garland’s right wing. Rosser and Pelham retreated north to Daniel Wise’s farm, which straddled the Old Sharpsburg Road. Like his division commander, Garland was fearless during the heat of battle. Garland was making adjustments to the deployment of the 13th North Carolina when he suffered a mortal wound in the chest from a minie ball.

Colonel Duncan McRae of the 5th North Carolina immediately took charge of Garland’s brigade. McRae sent a messenger with an urgent request for reinforcements to Hill. Anticipating the need for more troops on the mountain, Hill had already ordered George B. Anderson’s brigade to march to Turner’s Gap. It arrived just in the nick of time. Hill personally led Anderson’s 2nd and 4th North Carolina Regiments to McRae’s aid. Hill had told Anderson to take his other regiments to reinforce Colquitt.

By 11:30 am Cox’s division at Fox’s Gap controlled all of the ground south of the Old Sharpsburg Road on the ridge top. For a time, Bondurant’s and Pelham’s guns and Anderson’s two regiments kept the Federals from advancing north of the Old Sharpsburg Road. McRae withdrew the remnants of Garland’s brigade to the west side of the mountain. At that point, a lull in the fighting occurred as Cox waited for the other IX Corps divisions to arrive on the mountain.

While Garland was heavily engaged, Hill had ordered Ripley, Rodes, and Lt. Colonel Allen Cutts’s Reserve Artillery Battalion to march to Turner’s Gap. He also sent an urgent request for reinforcements to Longstreet. Hill’s last two brigades arrived at about 11:30 am, just as Hill was leading Anderson’s regiments south to assist McRae. When Hill returned to Turner’s Gap, he ordered Rodes to cover Colquitt’s left flank and directed the rest of George B. Anderson’s brigade and Ripley’s brigade to Fox’s Gap. Rodes deployed his brigade on two spurs just north of Turner’s Gap to block access to the Dahlgren and Frosttown Roads that would allow the Federals to outflank Turner’s Gap from the north.

At noon, the vanguard of Longstreet’s forces arrived at Turner’s Gap. Two brigades of Brig. Gen. David R. Jones’s division, those of Brigadiers Thomas Drayton and George T. Anderson, arrived panting after the 13-mile forced march from Hagerstown. Hill ordered them to march south along the ridge to Fox’s Gap.

Hill heavily reinforced his right at Fox’s Gap at noon with the intention of defeating the Federal threat to his right flank before the Federals struck his left flank at Frosttown Gap. With this in mind, Hill ordered Ripley, who was the senior brigadier at Fox’s Gap, to launch a counterattack using all four Confederate brigades.

Ripley formed the four brigades into a battle line along the Old Sharpsburg Road. Drayton’s brigade was on the left flank. Drayton deployed his forces on the Wise farm, his three Georgia regiments facing east and his two South Carolina regiments facing south. The other three brigades—George T. Anderson’s, Ripley’s, and George B. Anderson’s—deployed on Drayton’s right flank. The deployment left Drayton dangerously exposed if he were to be attacked simultaneously from the south and east.

While Ripley was getting his brigades ready for the next phase of battle, the 3,000 Yankees of Brig. Gen. Orlando Willcox’s division marched up the Old Sharpsburg Road to reinforce Cox. Meanwhile, to the north Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s 15,000-strong I Corps was slowly approaching Frosttown Gap. Both Hooker and Reno were cautious because they wrongly believed that Longstreet’s entire command had been at Boonsboro and therefore was already deployed atop South Mountain.

It took an agonizingly long time for the right wing of the Union attack against Turner’s Gap to get under way. Hooker ordered two divisions to advance in a flanking move. Although Brig. Gen. George Meade’s division arrived at the base of the mountain at 1 pm, he was directed to wait for the rest of the corps to get into position before attacking. Meade was to advance on the right directly up the Frosttown Road, while Brig. Gen. John Hatch advanced on Meade’s left along the Dahlgren Road, which joined the National Pike near Hill’s headquarters at the Mountain House. Together the two divisions numbered approximately 8,000 men. As a diversion to pin down Confederate forces, Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s 1,300-man brigade of Hatch’s division was to advance straight up the National Pike.

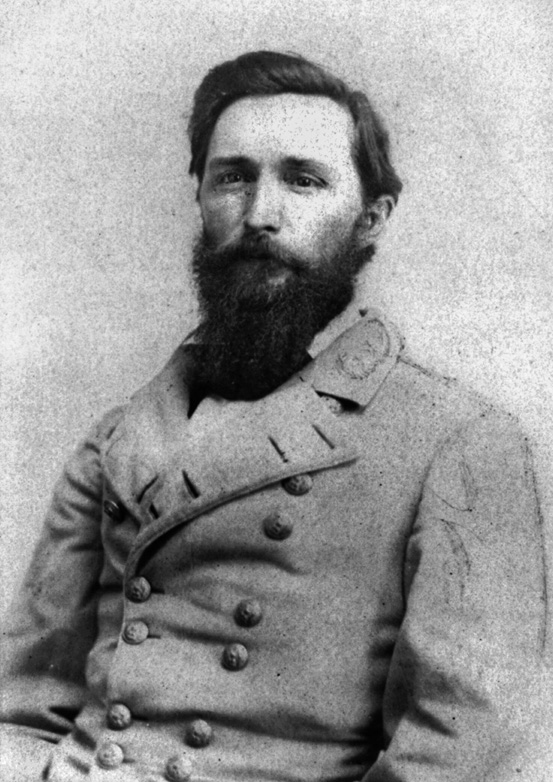

Two spurs of South Mountain straddled the Frosttown Road north of Turner’s Gap. Rodes’s 1,200-man brigade had the near impossible task of covering both against formidable odds. A graduate of Virginia Military Institute, the dashing 33-year-old did not shrink from the task at hand. From his perch observing the battle, Hill spotted Meade’s column and ordered Rodes to shift his line to the north so that he covered the northern spur and the defile between the two, but not the southern spur. Rodes objected, insisting that the southern spur also should be covered. Hill agreed, and he granted permission for the 12th Alabama to occupy the southern knob.

Shortly after 3 pm Meade’s men drove back skirmishers from the 12th Alabama. Working to Rodes’s advantage were the thick woods that concealed the size of his force from Meade. The 5th Pennsylvania Reserves had their hands full trading volleys with Gordon’s crack 6th Alabama on Rodes’s left flank. A charge by Gordon drove the bluecoats back at one point. Shells from batteries belonging to Rebel guns posted at Turner’s Gap crashed through the treetops, rattling the blue ranks. Two brigades of Yankees pushed up the defile, steadily driving back the 3rd and 26th Alabama Regiments. The Alabamians’ fire for the most part was too high. Most of their bullets whizzed harmlessly over the heads of the attacking Pennsylvanians, but when they made contact they inflicted deadly head wounds.

“In the first attack of the enemy up the bottom of the gorge they pushed on so vigorously as to separate the 3rd from the 5th Alabama Regiment,” wrote Rodes. Still, the Confederates got in their licks. Colonel Cullen Battle, commanding the 3rd Alabama, ordered his men, who were well concealed behind rocks, to hold their fire until the Yankees were almost on top of them before he gave the order to fire. A wall of flame erupted from the 3rd Alabama that staggered the lead elements of Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour’s brigade. The Alabamians owed their survival to the rugged terrain they were holding. They huddled behind whatever natural protection they could find to reload before emerging to fire at the bluecoats advancing slowly through the underbrush.

Meade had 13 regiments under his command, and he steadily fed fresh regiments into the fight in an effort to break the gray line. The fortunes of Rodes’s regiments varied greatly. On Rodes’s right, Colonel Edward O’Neal’s 26th Alabama became completely demoralized upon their colonel’s wounding and fled through the woods with the Yankees on their heels. In contrast, Gordon had kept his regiment “constantly in hand, and had handled it in a manner I have never seen heard or equaled [so far] in this war,” wrote Rodes. The pressure on Gordon was so great, though, that he was forced to withdraw from the northern spur to prevent being encircled. Rodes’s brigade lost 400 men, a third of its strength.

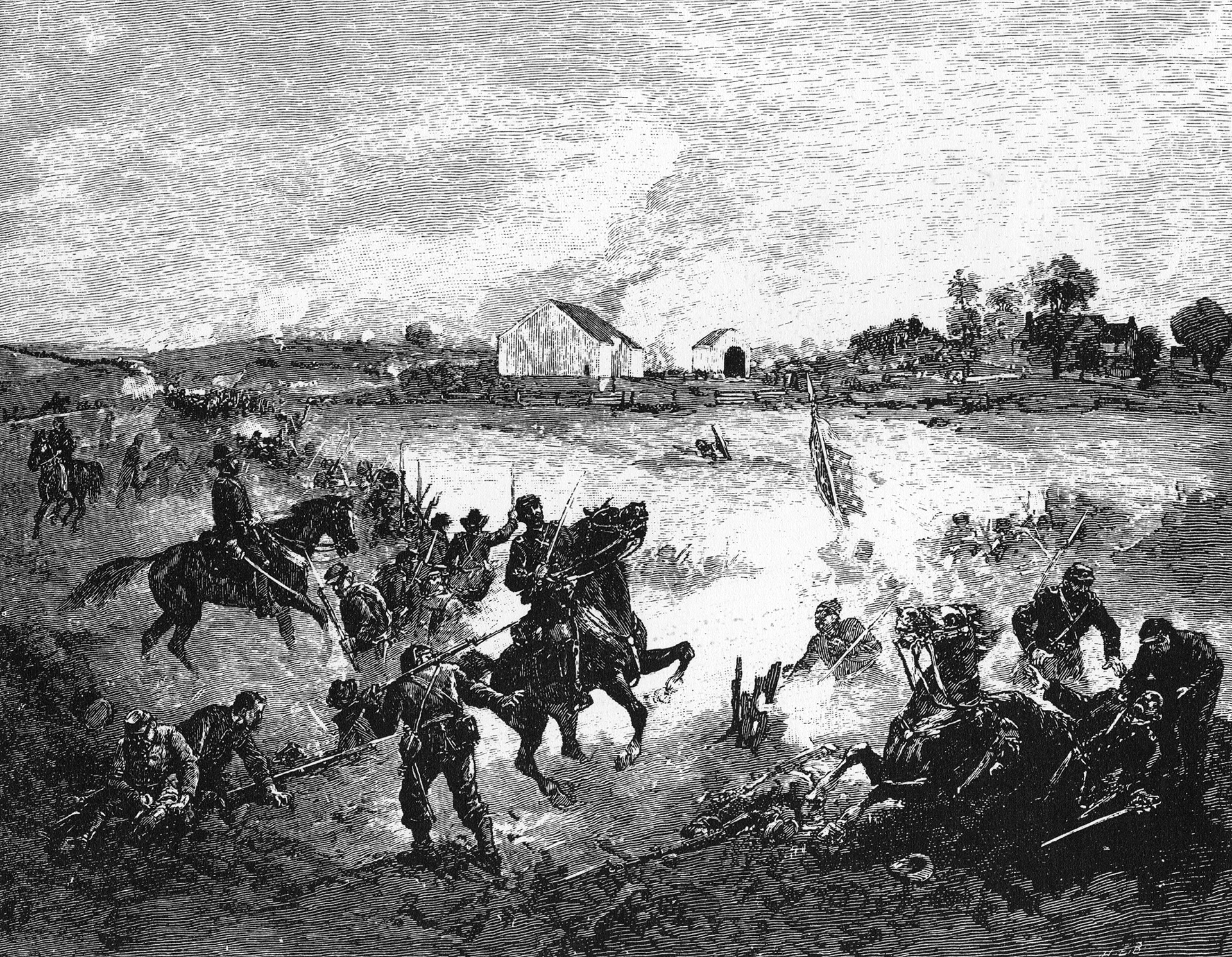

By 4 pm all four divisions of the Federal IX Corps were in place to dislodge Ripley’s ad hoc division at Fox’s Gap. The two divisions in advance, Willcox’s and Cox’s, advanced against Drayton’s salient on the Wise farm. Colonel Thomas Welsh’s brigade of Willcox’s division tied into Cox’s right flank and advanced south of the Old Sharpsburg Road against Drayton’s right flank, held by 500 South Carolinians, and Colonel Benjamin Christ’s brigade advanced north of the road toward Drayton’s left flank, held by 750 Georgians. The other three Confederate brigades at Fox’s Gap, which should have been facing east, were facing south. Ripley had allowed a dangerous 300-yard gap between Drayton’s right flank and George T. Anderson’s brigade that left Drayton’s right flank open to being turned.

About the same time the Federals advanced, Drayton ordered his South Carolina troops to advance south in compliance with Ripley’s order for a counterattack. Screaming the famous Rebel yell, Drayton’s South Carolinians ran headlong into a line of attacking Yankees. Lt. Col. John Curtin’s 45th Pennsylvania was the first to engage Drayton’s brigade. The South Carolinians fell back almost immediately in the face of Curtin’s attack. With smoke obscuring the summit of the mountain, some of Drayton’s men on the Old Sharpsburg Road fired at their fellow soldiers as they fell back through farmer Wise’s fields.

Meanwhile, Colonel William Withington’s 17th Michigan, a green regiment, advanced toward the Georgians. The Michigan troops had only a rail fence for protection while Drayton’s Georgians fired from the kneeling position behind a stone wall. Their blistering fire inflicted heavy casualties on the Michiganders.

Eventually Drayton’s right flank crumbled from the pressure of Welsh’s brigade supported by Cox’s troops. The men of Lt. Col. George James’s 3rd South Carolina made a desperate stand at the Wise house, firing from whatever cover they could find, but they were subjected to a hail of unrelenting fire from Welsh’s brigade, which overran their position. James was killed in the fight and all except 24 of his 160 men were killed or wounded. Drayton’s brigade lost 643 of its approximately 1,250 men.

Hill later criticized Ripley for failing to organize a coordinated defense of the gap. Only Drayton’s brigade had fought against the two Federal divisions. Ripley’s other brigades “did not draw a trigger, why, I don’t know,” Hill wrote. The Confederates lost 1,100 men at Fox’s Gap.

When Longstreet arrived at Turner’s Gap at 4 pm with the rest of his troops, he took control of the South Mountain battlefield as senior commander. When he learned of the desperate situation facing Drayton, Longstreet ordered Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood to march his two brigades to Fox’s Gap. Hood’s men deployed north of the Old Sharpsburg Road. After assessing the situation, Longstreet sent a message to Lee informing him that he intended to conduct a general withdrawal once it was dark.

Also arriving in the late afternoon at Turner’s Gap was the rest of Jones’s division and Brig. Gen. Nathan Evans’ independent brigade (led by Colonel Peter Stevens). These four exhausted brigades had not only marched 13 miles from Hagerstown, but an additional five miles. This was because Lee, who had arrived at the western base of Turner’s Gap at mid-afternoon, had sent them first to reinforce Fox’s Gap from the west, and then recalled them to go to Turner’s Gap. As a result of straggling, only 1,200 men from this force arrived at Turner’s Gap, which was the equivalent of one Confederate brigade.

While Hood’s two brigades remained north of the Old Sharpsburg Road to prevent the Federals at Fox’s Gap from reaching Turner’s Gap from the south, Longstreet ordered the last of his troops to support Rodes. Stevens’s 550 South Carolinians filed into position on the southern spur to check Hatch’s advance. The other three brigades—Brig. Gen. James Kemper’s, Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins’s (led that day by Colonel Joseph Walker), and Brig. Gen. George Pickett’s (led that day by Richard Garnett)—deployed on Stevens’ left to cover Rodes withdrawal.

From that point forward, the battle was Longstreet’s fight and the remainder of the fighting occurred at Turner’s Gap. Colonel Albert Magilton’s Pennsylvanians advancing on Meade’s left flank drove back Stevens’s exhausted Palmetto Staters. Kemper, Walker, and Garnett deployed to the right of Stevens on the Dahlgren Road. Brig. Gen. John Hatch’s 2,400 men forced all three brigades to retreat up the mountain toward the Mountain House. As for Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s weak diversionary attack, it did not budge Colquitt’s brigade.

Under cover of darkness, the Confederates withdrew. From sun up to sundown, Hill had remained calm and focused in the face of overwhelming odds. It is fair to say he saved the army, although Longstreet also deserves credit. In the desperate fighting at Fox’s and Turner’s Gaps, the Confederates lost 2,300 men to the Federals’ loss of 1,800 men.

In his battle report, Hill foolishly criticized Longstreet’s handling of the second phase of the fighting at Fox’s and Turner’s Gaps. “Maj. Gen. Longstreet came up about 4 pm with the commands of brigadier generals N.G. Evans and D. R. Jones,” Hill wrote. “I had now become familiar with the ground, and knew all the vital points, and, had these troops reported to me, the result might have been different. As it was, they took wrong positions, and, in their exhausted condition after a long march, they were broken and scattered.”

Longstreet’s command, including Hill’s division, withdrew to the high ground around Sharpsburg on September 15 to await the arrival of Jackson’s command. Following the surrender of the Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry, Jackson arrived in Sharpsburg on September 16 with all but one of his divisions.

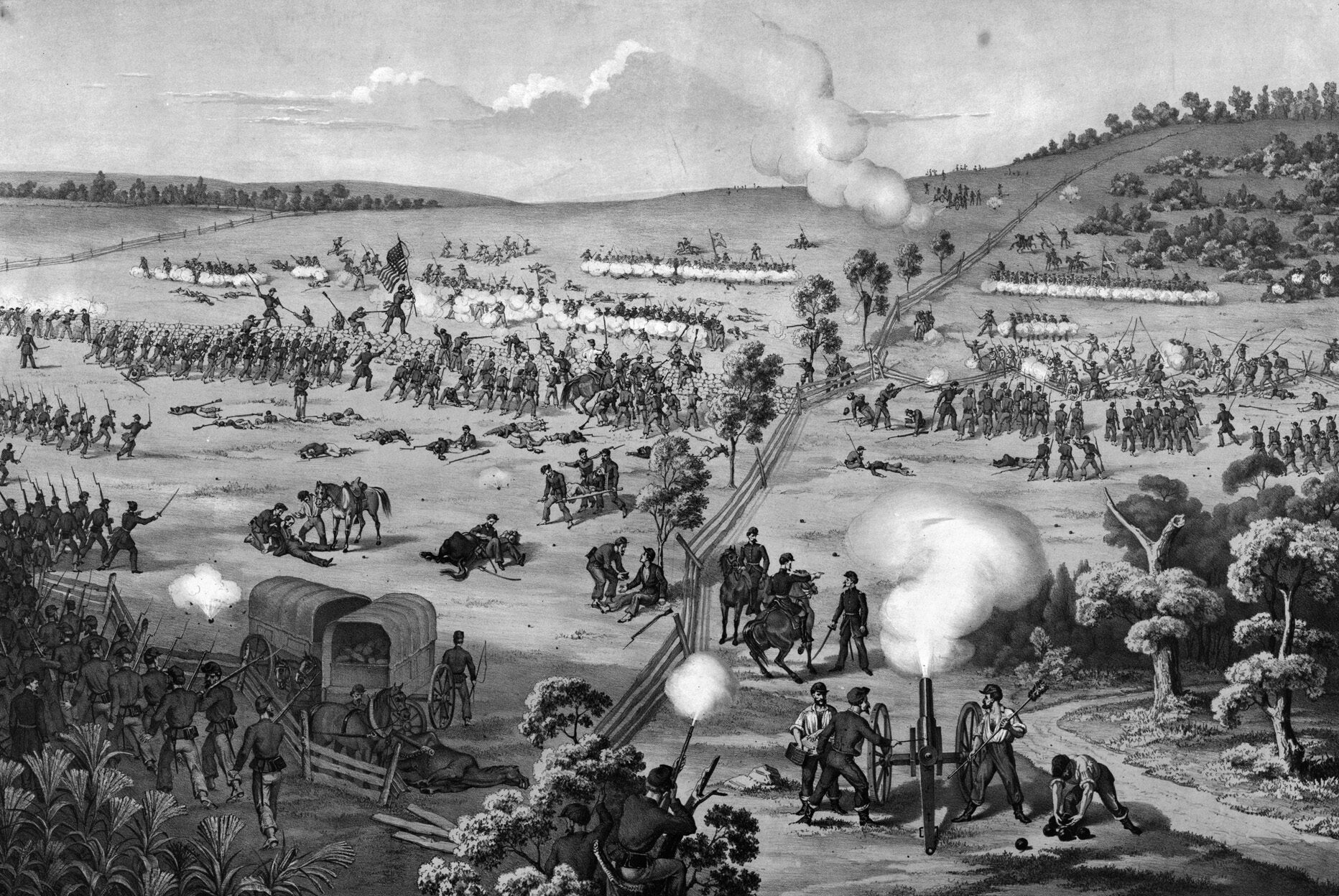

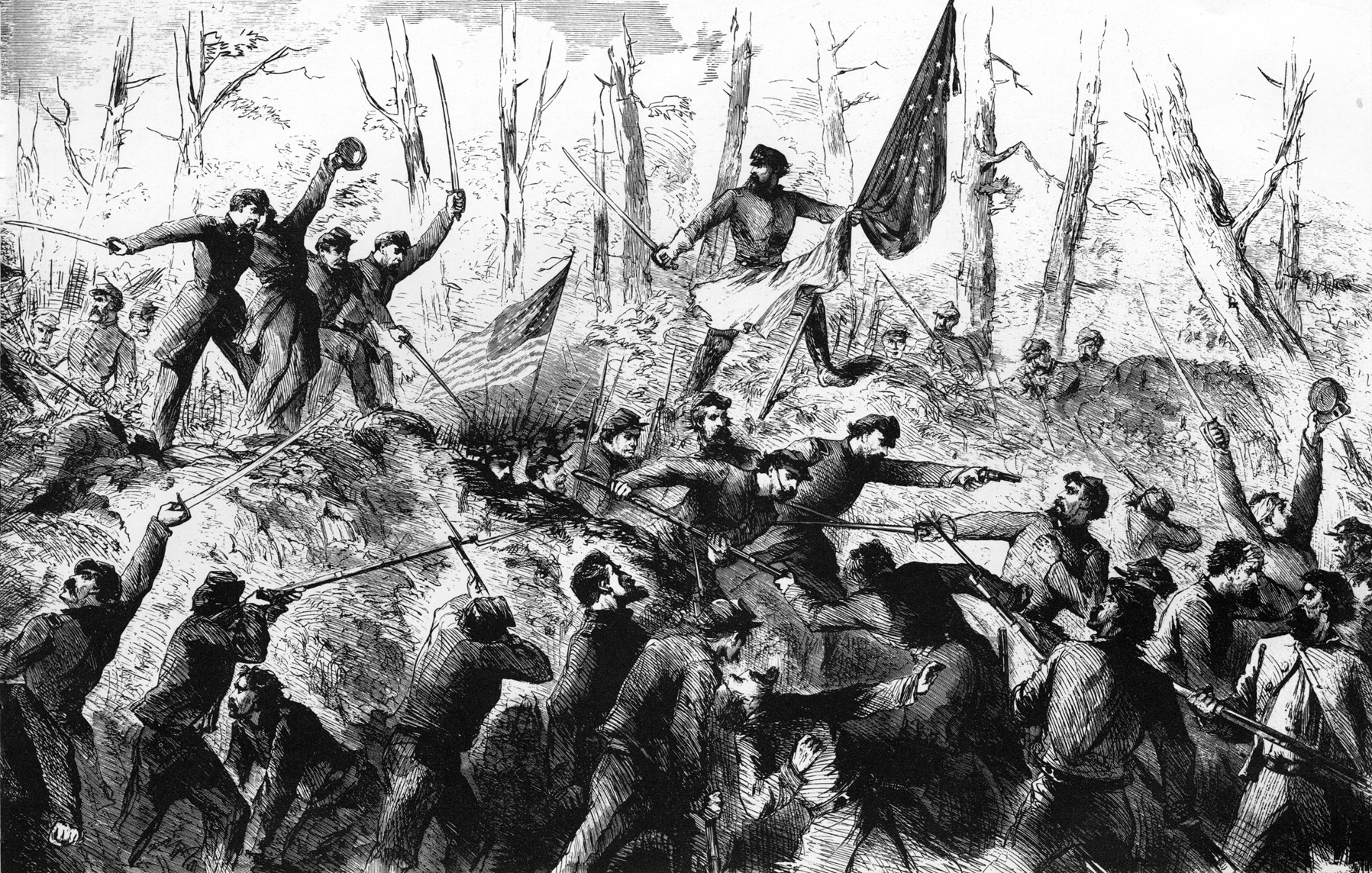

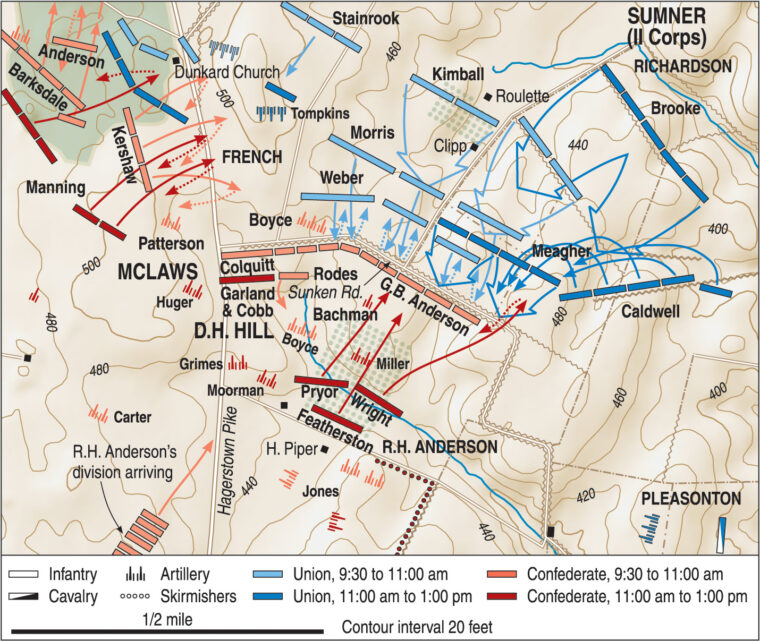

On the high ground on the west bank of Antietam Creek, Longstreet ordered Hill to post his men in the center of the Confederate line. Hill’s line stretched from the Boonsboro Pike to the Smoketown Road. The North Carolinian set his men to work improving the natural trench afforded them by the deeply worn farm road known after the battle as the Bloody Lane. The men collected fence rails and stacked them in front of the road to serve as a crude breastwork.

Major General Joseph Hooker’s I Brigade opened the battle at 6 am with an attack on the Confederate left. After an hour of hard fighting, Jackson appealed to nearby commanders not yet engaged for whatever reinforcements they could send. Hill initially sent the brigades of Colquitt and Ripley, and a half hour later sent Garland’s brigade (led by Colonel Duncan McRae). This left the Sunken Road uncovered, so Hill shifted Rodes and George B. Anderson to the key position. Rodes’s men filed into place on the left of the salient, and George B. Anderson’s men took up a position on the right. Longstreet ordered Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb’s brigade, from another division, to cover Rodes’s left. Altogether, Hill had about 2,500 men ready in the center of the battlefield.

Major General Edwin Sumner’s three divisions of the II Corps joined the battle. Sumner’s three divisions attacked in echelon from north to south over a period of 90 minutes. Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s division was repulsed with heavy casualties when it attacked Jackson’s command at 9 am. Going into battle south of Sedgwick at 9:30 am were the 5,700 Yankees in three brigades belonging to Maj. Gen. William French. The Marylander’s three brigades advanced through the Roulette Farm toward Rodes’s side of the Sunken Road salient. “A heavy force … advanced in three parallel lines, with all the precision of a parade day, upon my two brigades,” Hill wrote. “They met with a galling fire, however, recoiled, and fell back; again advanced, and again fell back, and finally lay down behind the crest of the hill and kept up an irregular fire.” The bloody hour-long assault failed to carry Rodes’s position.

At 10:30 am, Maj. Gen. Israel Richardson’s division emerged from the creek valley. Richardson launched a determined assault on George B. Anderson’s brigade on the right side of the Sunken Road position. Just before French’s attack, Hill had sent an urgent message to Longstreet for reinforcements. The burly South Carolinian ordered Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson to march his 3,400 men from their position in the Confederate reserve at Sharpsburg to Hill’s aid. Richardson’s Yankees fought with grim determination standing on the slope above the Sunken Road pouring volleys into George B. Anderson’s North Carolinians. As the fighting intensified, a Yankee bullet struck George B. Anderson in the ankle, taking him out of the battle. He would die one month later from complications related to the wound.

In adherence with Longstreet’s order, Richard Anderson’s four brigades moved into the 15-acre apple orchard and large cornfield of the Piper Farm behind the Sunken Road. The Confederate reinforcements immediately were the target of Richardson’s infantry, as well as Union rifled guns on the high ground east of Antietam Creek. In the maelstrom of iron and minie balls that swept the Piper fields, Richard Anderson received a thigh wound that took him out of the battle. The absence of a divisional commander severely reduced the effectiveness of Richard Anderson’s brigades. Brig. Gen. Ambrose Wright’s Georgians furnished some support to George B. Anderson’s hard-pressed regiments. But Colonel Carnot Posey, who was commanding a brigade that day, led his Mississippians past the Sunken Road in a counterattack that produced heavy casualties.

About 11:30 am the Confederate line began to waver. Colonel Risden Bennett of the 14th North Carolina had assumed command of George B. Anderson’s brigade just as the last of Richardson’s fresh troops struck the gray line. While awaiting the attack of Brig. Gen. John Caldwell’s brigade, Richard Anderson’s troops milled about without clear direction. When the fighting flared up again they “broke beyond the power of rallying after five minutes’ stay,” Bennett wrote. Caldwell’s bluecoats launched a fresh attack. They advanced shouting and delivered crashing volleys into the Confederates on Hill’s right. As the fighting rose to a crescendo, groups of Rebels on the right side of the Sunken Road began falling back without orders. When Posey ordered the remnants of his shattered brigade to withdraw, all of Rebel regiments on the right side of the Sunken Road withdrew.

This left Rodes’s right flank dangerously exposed. Gordon, whose 6th Alabama was stationed on Rodes’s right flank, received his fifth wound of the day and left the battle. Rodes saw the need to refuse his brigade’s flank, and he ordered Lt. Col. James Lightfoot, the 6th Alabama’s next in command, to pull back to the ridge behind the farm road. Lightfoot misunderstood the order and led his men back farther than Rodes intended. The other regimental commanders saw the 6th Alabama leave, and they wrongly assumed Rodes had ordered the retreat of the entire brigade. Richardson’s Yankees advanced to occupy Rodes’s portion of the Sunken Road. Unless Hill and Longstreet took immediate action to rally Hill’s and Richard Anderson’s men, the Federals might be able to fight their way through the Confederate center to Sharpsburg.

Longstreet cobbled together some troops for a counterattack against French’s division. He ordered Colonel John Cooke, the commander of the 27th North Carolina in Brig. Gen. John Walker’s brigade, to bring the remnants of Walker’s brigade from the Confederate left to reinforce Rodes. Although Longstreet intended Rodes and Cooke to advance together, the unexpected retreat of the Alabamians derailed the counterattack. Cooke led his 675 men through the high corn on Samuel Mumma’s farm against French’s right flank. Union Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball quickly ordered his men to change front. The two sides exchanged heavy volleys at just 200 yards. Cooke’s Rebels got the worst of it. When they ran out of ammunition, they withdrew having lost half of their number.

Meanwhile, Longstreet gathered as many available cannons as he could find and directed them to deploy on the Piper Farm to buttress the Confederate center. As Confederate infantry officers attempted to rally the remnants of their respective commands, the Confederate artillerists fired case shot and canister at the Federals in the Sunken Road. As many as 20 Rebel guns pounded the Federals. Sumner had deliberately kept all of the division’s artillery in the East Wood to the north in anticipation of a Confederate counterattack against Sedgwick’s division, which left French and Richardson with no direct artillery support to counter Longstreet’s guns. The crews of the Federal long-range guns on the east side of Antietam held their fire for fear of shelling their own men, who were now in the Sunken Road.

To further harass the Federals, Hill led two unsuccessful counterattacks. The first one was an attempt to drive the Yankees from George Anderson’s former position, and the second was an attempt to force them to retreat from Rodes’s section of the Sunken Road. Neither succeeded, but they kept the Yankees off balance. Hill’s leadership, again with Longstreet’s assistance, staved off a possible disaster in the Confederate center. Hill’s division lost a total of 2,316 killed, wounded, or missing in the Antietam campaign.

During the winter of 1862-1863, Harvey Hill griped about not being among the select few chosen by Confederate President Jefferson Davis for lieutenant general. Lee chose Longstreet and Jackson to serve as lieutenant generals commanding his first and second corps, respectively, in the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee also indicated that the closest runner-up had been Virginian Ambrose Powell Hill (no relation to Harvey Hill). This undoubtedly bothered Harvey Hill as he had seniority over Powell Hill.

Lee had accurately pegged Harvey Hill as someone who complained far too much. Word got back to Lee during the Seven Days Battle and the Antietam Campaign that Hill had been highly critical of Lee’s tactical decisions, and also of the decisions of his commanding officers, such as Longstreet. An official in the Confederate War Department articulated Hill’s pessimistic attitude. Hill was “harsh, abrupt, often insulting in the effort to be sarcastic,” the official wrote, adding that Hill was most likely in a situation that called for diplomacy instead of an attitude likely to “offend many and conciliate none.”

Hill’s division, which formed part of the Confederate reserve at Fredericksburg, did not fight in the December 13 battle. This gave Hill plenty of time to plan his next move. Feeling slighted for not having been promoted to lieutenant general, Hill submitted his resignation to Lee on January 1, 1863, citing his deteriorating health as his reason. In the letter, Hill noted he had fought in 11 key battles since the beginning of the war. Although the details are not clear, Lee somehow managed to persuade the North Carolinian to rescind his resignation and once again take command of the Department of North Carolina.

On July 11, 1863, Davis informed Hill that he had been promoted to lieutenant general subject to confirmation by the Confederate Senate. In that capacity, Davis ordered him to report to General Braxton Bragg to assume command of a corps in the Army of Tennessee. Hill led his two-division corps ably at the Battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga in late 1863, but afterwards became embroiled in a feud with Bragg. When Davis intervened, he sided with Bragg. The Confederate president was so disgusted with Hill that he refused to submit his promotion to lieutenant general for confirmation to the Confederate Senate.

In the last year of the war, Hill served in a variety of posts in secondary theaters, including as an aide to P.G.T. Beauregard at Petersburg for five weeks in the spring of 1864, then in the defense of Lynchburg, Virginia, and in command of the District of Georgia in January 1865. The latter post led to a brief return to division command under General Joseph Johnston at the Battle of Bentonville in March 1865. Hill passed away in Charlotte, North Carolina, on September 24, 1889, and was buried in Davidson College Cemetery.

Hill’s testy personality tarnished his legacy as a great fighter, and undoubtedly prevented him from an even greater career with the Army of Northern Virginia in the second half of the war. If he had only gotten along better with Lee, he might very well have commanded a corps in the Army of Northern Virginia during its latter days and received formal confirmation of a promotion to lieutenant general. Hill had only himself to blame for not achieving that goal.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments