By William E. Welsh

The barefoot crusaders tramped slowly underneath a blazing sun behind bishops and priests chanting and holding aloft relics on July 8, 1099. Their skin was burned and blistered by the unmerciful furnace in the sky, and their lips were parched and tongues swollen from constant thirst. The barren and dusty landscape, which was the color of a tanned animal hide, offered them no protection from arrows fired by the Egyptian garrison. As they marched through the Quidron Valley under the south wall of Jerusalem, they passed the Pool of Siloam. The approaches to the spring were littered with the carcasses of dead pack animals, which seeking to alleviate their thirst, had either died before reaching the spring or died upon finding it dry.

The idea for the liturgical procession came from Frankish priest Peter Desiderius, who after the crusaders had been encamped outside Jerusalem for a month, claimed that the spirit of the deceased Bishop Adhemer de le Puy, the leader of the First Crusade who had died 11 months earlier at Antioch, appeared to him in a vision on July 6, 1099. In the vision, Adhemer stated that the Frankish princes should stop bickering among themselves. In addition, all 15,000 of the crusaders should walk barefoot in the manner of the apostles in a procession that would sanctify them from their impurities. If these things were done, Adhemer told Desiderius, in the next nine days the crusaders would capture Jerusalem.

The Christian princes, knights, and commoners all embraced the idea. After passing through the Valley of Josephat below the east wall of the town, the barefoot crusaders continued east to the Mount of Olives where Jesus had ascended to heaven after the resurrection. As they toiled in the following days to build the siege engines that would be necessary to gain entry into Jerusalem, they were spurred to superhuman efforts by their desire to revenge themselves upon the Muslim soldiers who had mocked them.

“While we marched around the city, the Saracens and Turks made the circuit on the walls ridiculing us in many ways,” wrote crusader historian Raymond of Aguilers. “They placed many crosses on the walls in yokes and mocked them with blows and insulting deeds. We, in turn, hoping to obtain the aid of God in storming the city by means of these signs, pressed the work of the siege day and night.”

Although the Latin Christians were slowly pushing back the Muslims in Western Europe in the 11th century, the Byzantine Empire in the East was in grave peril. Following the decisive defeat of Emperor Romanos IV’s army by Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan’s forces at Manzikert in eastern Anatolia on August 27, 1071, the empire lost nearly all of its Asian lands to the Seljuk dynasty.

The victory at Manzikert was a continuation of the ascendency of the Muslim Seljuks begun by their founder Tughril, who had conquered Khorezm, Persia, and Iraq earlier in the century. In 1055, Tughril was proclaimed sultan in Baghdad. Arslan, who succeeded Tughril, continued the Seljuk tide of conquest by conquering Georgia, Armenia, and Syria and grabbing nearly all of the Byzantine territories in Anatolia.

Fearing for the survival of Byzantium and the safety of Christians living behind a Muslim curtain, Byzantine Emperor Michael VII, who succeeded Romanos IV, appealed to Pope Gregory VII for military assistance to fight the Turks. But Gregory, and a later pontiff, Urban II, had something far more grandiose in mind.

Urban II wanted the Latin monarchs and princes to stop fighting among themselves and focus instead on spreading Roman Christianity to new lands. The most obvious target of such ambition was Palestine and the city of Jerusalem, which housed the Holy Sepulcher. The Muslims had controlled Jerusalem since 638 when Abu Ubaidah’s Rashidun army captured it from the Byzantines. In addition to assisting the Byzantines against the Seljuks, Urban II also wanted to protect the large numbers of Latin pilgrims who visited Jerusalem.

In late November 1095, Urban II summoned Western European princes and soldiers to participate in a large-scale military expedition to liberate Palestine, and Jerusalem in particular, from the Muslim grip. “All Christendom is disgraced by the triumphs and supremacy of the Muslims in the east,” Urban II said at the Council of Claremont. In return for their service freeing Jerusalem from the infidels, the pope offered a blanket penance for all confessed sins.

Urban set out in December 1095 on a nine-month tour of France in which he preached the crusade. The response was overwhelming. Hundreds of thousands of people wanted to participate in the pilgrimage. The logistics were mind boggling. The journey would take them 2,000 miles from their homes and towns to unknown and hostile lands. A force equal to or greater than the lure of religious salvation was the belief held by many that they would find riches and fame in the East.

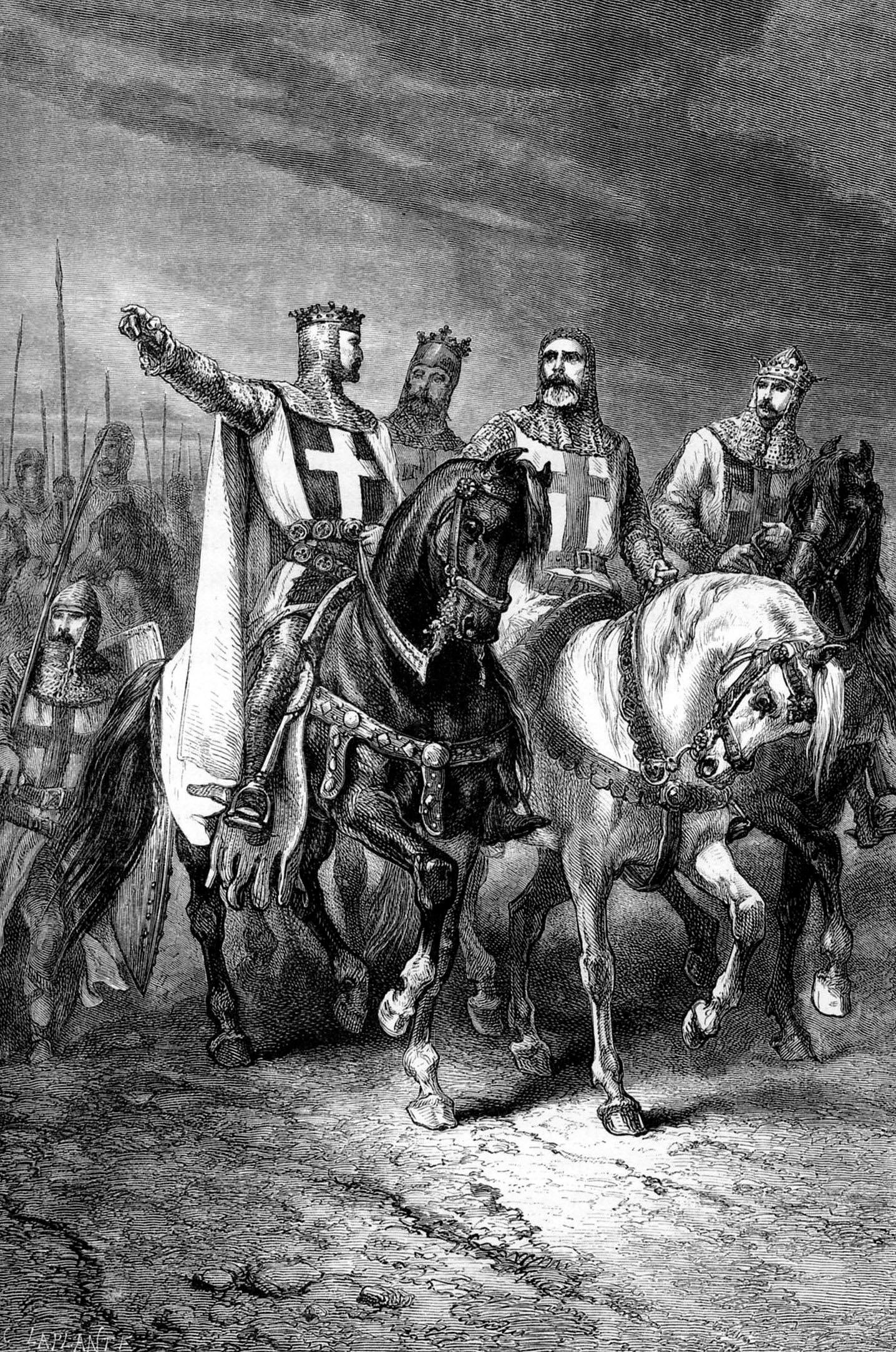

Upward of 90,000 Europeans responded to the pope’s call. To Urban’s disappointment, however, none of the kings of Western Europe responded. Nevertheless, a great many prominent princes with ample military experience took the cross. The most prestigious among the princes were Godfrey of Boulogne, Duke of Lower Lorraine; Duke Bohemond of Taranto; Count Raymond of Saint-Gilles; Count Stephen of Blois; Duke Robert of Normandy; and Count Robert of Flanders. Bohemond’s nephew, Tancred of Hauteville, also took the cross, as did Godfrey’s brothers Eustace and Baldwin and his cousin Baldwin of le Bourcq.

Urban set the Day of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, August 15, 1096, as the official start of the pilgrimage. He appointed Bishop Adhemer of le Puy as the leader of the crusading army. Each of the lords brought along his household knights and his own contingent of foot soldiers.

Although Urban likely had in mind that the crusading army would be composed of professional soldiers, it came to pass that a mass of peasants also intended to make the pilgrimage to Jerusalem. A number of wandering priests, the most famous of whom was Peter the Hermit, created a crusading fervor among the common people. Two large groups of poorly armed people numbering about 20,000 constituted the first wave of crusaders to reach Constantinople. This crusading army, known as the People’s Crusade, arrived in Constantinople in July 1096.

Byzantine Emperor Alexius I was extremely disappointed when the peasants in the People’s Crusade arrived at Constantinople. He wasted no time in ordering them ferried across the Bosporus, an event that occurred on August 6, 1096. Once they were on the Asian side of the Bosporus, the peasant crusaders marched toward Nicea. The Seljuk army ambushed the peasant army in October. When the fighting was over, those peasants who survived the ordeal were given the chance to convert to Islam or be slain. Their futile crusade had no influence on the state of affairs in Anatolia.

The second wave of crusaders, the professional soldiers, would arrive in Constantinople throughout the winter of 1096-1097. Duke Godfrey’s 30,000-strong force of northern Franks departed on August 15, marching along a similar overland route. This army arrived outside Constantinople on December 23.

Alexius and the leaders of the second wave of crusaders, which was the one that Pope Urban had envisioned when he preached the crusade, had divergent goals. For his part, Alexius had no interest in capturing the Holy Lands. He simply wanted mercenaries to help him win back the pre-Manzikert Byzantine territories. For their part, the crusading army wanted to get as quickly as possible to the Holy Land, where it would liberate Jerusalem and plunder Muslim-held lands. The leaders of both sides had large egos, and tempers flared when some of the Franks plundered Byzantine territory in Europe on their way to the rendezvous at Constantinople.

Knowing that it was in his best interests to find middle ground that satisfied each party’s interests, Alexius proposed that the Frankish leaders swear an oath as vassals to the Byzantine emperor and promise to hand over to the emperor any lands that they conquered in Anatolia on their eastward march. Some of the Western princes balked at having to pledge an oath to the emperor as their liege, but nearly all did in one form or another. In return Alexius pledged to supply the crusaders and also to share valuable military intelligence with them.

After the agreements had been made, the Byzantines began ferrying the 60,000 Franks to the Asian side of the Bosporus. The vanguard of the crusading army departed Nicomedia inside the Byzantine border on April 29, 1097. The Franks tramped through the defile near Civetot, where the sun had bleached the bones of many of the unlucky participants in the People’s Crusade who had been slaughtered by the Seljuk Turks. They reached Nicea on May 6 and camped outside the city’s thick walls. At the time, the stronghold was the capital of the Sunni Muslim Sultanate of Rum, one of the sultanates within the Seljuk Turks’ confederated structure. When the Franks arrived, Sultan Kilij Arslan I was campaigning in eastern Anatolia. It was not until June 3 that all of the various divisions that made up the crusading army were assembled before Nicea. On June 19, the garrison, realizing it was heavily outnumbered, surrendered to the Franks, who turned over the city to Alexius and resumed their march.

On June 26, the crusading army departed Nicea on the old Byzantine road. The princes held a council of war at the village of Leuce in the Sangarius Valley in which it was decided to divide the army into two smaller armies for logistical reasons. Bohemond would lead the first army, which comprised the Northern Franks and the Normans of Italy. Raymond commanded the second army composed of the southern Franks and the Lorrainers. From Leuce the road turned south. Bohemond was unaware that Kilij Arslan, with a powerful host, was waiting near Dorylaeum to ambush the Franks. In a desperate battle fought July 1 on a plain west of Dorylaeum, the Franks prevailed over the Seljuk Turks. Initially, Kilij Arslan drove the Franks back on their camp, but they fled when Raymond’s troops reinforced Bohemond’s beleaguered forces.

After he was defeated at Dorylaeum, Arslan decided to allow the crusading army to continue its march uncontested by his forces. At Heraclea in mid-September, a small part of the army broke off to march through the fertile region of Cilicia while the main army turned northeast toward Caesarea. The main army decided to take the longer route to Syria because it feared a possible ambush while passing through the narrow pass in the Taurus Mountains known as the Cilician Gates. Instead, the main crusading army opted to reach Syria by way of a wider pass in the Anti-Taurus Mountains.

Despite the danger of ambush in the Cilician Gates, Tancred and Baldwin of Boulogne led two separate bands of soldiers into Cilicia in search of loot. Tancred later rejoined the main crusading army when it reached northern Syria, but Baldwin continued east to the middle Euphrates valley. Baldwin assisted the aging ruler of Edessa, Lord Thoros, against the Muslims. When Thoros was subsequently killed during an uprising in the city in March 1099, Baldwin conveniently succeeded him. Baldwin shared the spoils of his conquest with his older brother, Godfrey, who in turn was able to pay his troops.

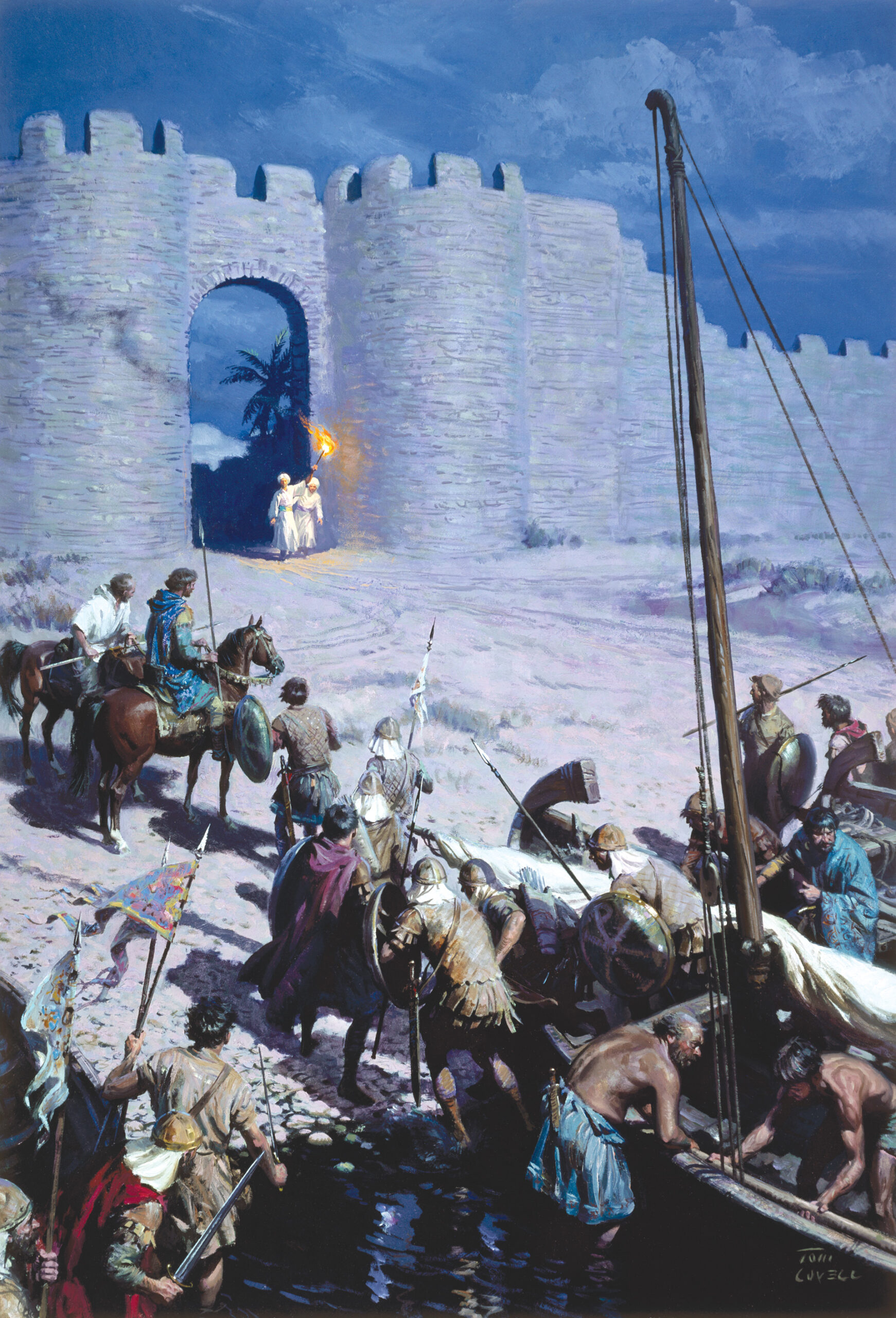

The main crusading army reached the Iron Bridge, a fortified crossing of the Orontes River, near the Muslim-held fortress of Antioch, on October 20. Although the Franks substantially outnumbered the 5,000 Turkish soldiers inside Antioch, the walls were so extensive that it was impossible for the crusaders to surround the city. The crusaders defeated Muslim relief forces from Damascus and Aleppo in December 1097 and February 1098, respectively. The hard-fought battles inflicted substantial casualties on the crusaders that could not be replaced. The city was finally taken, not by assault but by a traitor in the garrison who allowed a small group of crusaders to enter the city on the night of June 2. They, in turn, allowed other crusaders inside the city. The subsequent massacre after the eight-month siege spared neither the garrison nor some Eastern Christians.

On June 4, a third relief army arrived. The tables were turned, and the crusaders became the besieged army. Although the Franks were unsure they could defeat yet another Turkish army, Frankish crusader and mystic Peter Bartholomew supposedly found the Holy Lance, the spear that pierced Jesus Christ, in Antioch’s Basilica of St. Peter. Although the lance was a phony relic, the rank and file of the crusading army saw it as a divine sign. In a setpiece battle fought June 28, the crusaders defeated a third Turkish army.

In keeping with their oaths to Alexius I, the leaders of the crusades should have turned Antioch over to the Byzantines. However, Bohemond claimed the city for himself and his followers. This produced a rift between Bohemond and Raymond of Saint-Gilles, who together with Godfrey were the principal leaders of the crusade. Godfrey remained neutral. Unfortunately for the entire crusading army, Bishop Adhemer, who had been able to mediate disputes in similar situations, died on August 1 as a result of a sickness that swept through the ranks.

Through a mixture of military prowess, cunning, and sheer perseverance, the crusaders had triumphed at Antioch. They had made a remarkable comeback from the brink of disaster at the hands of the tenacious Seljuks, who had the advantage of fighting on their own terrain. Of the 40,000 crusaders who had managed to reach Antioch, only 20,000 were left by the end of the summer of 1098. The Franks had suffered heavy casualties in the protracted fighting at Antioch, and their ranks had been further thinned by disease.

More major challenges lay before the crusaders. They would have to march south through Muslim-held southern Syria, Lebanon, and Galilee before they reached Jerusalem. But they would find, as they moved south, that many of the local Arab dynasties feared them and were willing to pay them tribute if the crusaders refrained from pillaging their lands.

The bickering among the leading princes, specifically Bohemond and Raymond, threatened to unravel the armed pilgrimage to retake Jerusalem from the Muslims, which both the knights and commoners had pledged themselves to achieve. The situation was, in the words of Raymond of Aguilers, “a princely fiasco.” Anger and discontent in the ranks percolated up to the leadership and it became clear by late summer that it did not matter so much who led the march to Jerusalem as long as the march got underway. Raymond led his forces south in late September to pillage towns in northern Syria as a preliminary step in the march to Jerusalem.

After some initial successes, the southward advance bogged down on November 27 when Raymond besieged the walled city of Maarat in the Summaq Plateau. Bohemond, like a sulking child, followed with his forces because he was desirous of whatever spoils Raymond might obtain. With the added weight of Bohemond’s troops, the Franks fought their way into the town on December 11. The town was mercilessly sacked, and the two princes bickered over the spoils. The southward trek bogged down for another month before Raymond led his forces south on January 13.

The ranks of the crusading army swelled three days later when Duke Robert of Normandy and Tancred arrived with additional forces. When the Franks reached Shaizar on the upper Orontes, Raymond called a council of war. The main discussion centered on whether the crusaders should march along the coast or the interior to Jerusalem. Raymond argued that the coastal route would enable them to take advantage of supplies from Christian ships that they might make contact with on their march. Tancred argued that the coastal route would entail frequent fighting against the Arabs, and he suggested they march east of the coastal mountain ranges, even if that meant enduring scarce supplies. A compromise was struck whereby the crusaders would continue marching in the interior through southern Syria until they reached Lebanon. At that point, they would march along the coast; however, the princes agreed to refrain from unnecessary sieges.

Despite his agreeing to refrain from sieges, Raymond once again allowed a siege to slow the progress south when he tried to capture the town of Arqa in February in an effort to intimidate local Muslim emirs as the crusaders marched toward the coast of northern Lebanon. By that time, Duke Godfrey of Lower Lorraine and Count Robert of Flanders had joined the crusader army. However, Bohemond returned to Antioch to focus on establishing himself as its ruler.

By a show of force, Raymond hoped to compel the emir of Tripoli into paying tribute to the Franks. When Raymond learned that Tripoli’s emir refused his demands, he left a force behind to contain Arqa and marched against Tripoli. The Muslim garrison at Tripoli emerged to give battle and was repulsed with heavy losses by the Franks. After the defeat, the emir paid Raymond 15,000 gold pieces to spare his city and the surrounding environs. Raymond was loath to quit the siege of Arqa because it would make him seem weak in the eyes of the Arabs.

Raymond’s reputation suffered serious damage as a result of his continued association with Peter Bartholomew during that period of the crusade. The mystic’s ravings became intolerable; for example, he proposed that a number of crusaders who had sinned should be executed. On Good Friday, April 8, 1099, Peter agreed to a trial by fire to judge the legitimacy of his claims regarding the Holy Lance. He was compelled to walk through a stack of burning olive branches under the watchful gaze of both doubters and believers. He died shortly afterward as a result of complications from his wounds. In the aftermath, the majority of crusaders favored Duke Godfrey to lead them on the final leg of the march.

The crusaders broke off the siege of Arqa on May 19 and marched west, where they picked up the coastal road at Tripoli. Four days later they arrived in Sidon after a forced march of 75 miles. After resting several days, the crusaders resumed their forced march, reaching Acre on May 25. Most of the Muslim garrisons on the coast allowed the crusaders to pass unmolested, provided they did not take crops and livestock belonging to the locals. The Franks reached Arsuf on May 30 and rested for three days. This put them within a two-day march of Jerusalem, which was situated 50 miles southwest of Arsuf. They marched upward into the Judean Hills to Ramla, a town roughly halfway between the Mediterranean Coast and the Holy City. The Franks encountered no resistance when they marched into Ramla on June 3 because the inhabitants of the town had fled in fear of the invaders. The army rested again for several days. Tancred, probably at his own insistence, rode south to Bethlehem with 100 knights, arriving at dawn on June 7. He was welcomed with open arms by the Christian population.

Egyptian Emir Al-Afdal Shahanshah had retaken Jerusalem from the Seljuks in 1098 after a 40-day siege. The siege was carried out while the bulk of the forces under the command of the Seljuk governor of Mosul, Kerbogha, were tied up fighting the Franks at Antioch. Opposing the Franks were 2,500 Arab cavalry and Sudanese archers under Fatimid governor Iftikhar al-Dawla. Inside the walled city lived 30,000 civilians, most of whom were Christians. Al-Afdal had sent emissaries to the Latin army with an offer of an alliance against the Seljuks provided that the Franks allowed them to retain Jerusalem. The offer was flatly refused. Unfortunately for Al-Afdal, he completely misread the intentions of the Franks, and therefore he did not reinforce the Fatimid garrisons in Palestine that might have slowed the Frankish advance and eroded the Franks’ dwindling manpower.

Jerusalem was a walled city at the time it was conquered by King David of Israel in the 11th century bc. The Romans, Byzantines, Umayyads, and Fatimids all improved the walls during their rule over the city. At the time of the First Crusade, the city had six main gates. Three were on the north side, and one was on each of the other three sides. The Jaffa Gate next to the Tower of David where two walls came together at an angle on the west side was particularly strong. The tower was constructed of “solid masonry,” wrote crusader historian Fulcher of Chartres, and its large stones were “sealed with molten lead.” Because of the tower’s strength, the crusaders moved their encampments to other locations.

The Egyptian garrison benefitted from elevated strongpoints inside the castle. One of these was the Tower of David. Another was the Quadrangular Tower on the northwest corner of the city. Yet another was the expansive temple area on the east wall. The west, east, and south sides of the city all had ravines. Siege towers typically were built beyond the range of arrow fire and then rolled up to the walls. The steep slopes of the ravines surrounding most of Jerusalem made it nearly impossible to roll siege towers up to the walls on any side except the north.

The garrison had plenty of food and water, the latter of which was collected in large underground cisterns used to store winter rainwater, to endure a lengthy siege. But the Christians lacked sufficient water. Indeed, the residents of Judea had warned the Franks that the summer was the worst time to attack the city for this reason. The dry ground surrounding Jerusalem lacked streams and underground springs. The only water in the immediate area came from the Pool of Siloam, which flowed intermittently and was polluted.

The Franks had food but not nearly enough water, wrote Fulcher of Chartres. “Because that place was dry, unirrigated, and without rivers, both the men and the beasts of burden were very much in need of water to drink,” he wrote. “This necessity forced them to seek water at a distance, and daily they laboriously carried it in skins from four or five miles to the siege.” This resulted throughout the course of the siege in soldiers venturing over great distances to obtain water and then selling it at exorbitant prices to other soldiers.

The main body of the Frankish army, which by then numbered about 13,500 men, reached the outskirts of Jerusalem on June 7. A few days after its arrival, a Frankish falconer sent his bird of prey aloft to intercept a carrier pigeon. The falcon retrieved the pigeon, which carried a dispatch from Al-Afdal to al-Dawla in which the former stated that a relief army would arrive before the end of June. Mounted couriers also were intercepted bearing the same message. For this reason, the Western princes decided to attempt to take the city by storm as soon as possible.

In the week after their arrival, the Franks took up key positions on opposite ends of the city to stretch its defenses. The northern Franks encamped opposite the north wall. Robert of Normandy’s forces deployed opposite Herod’s Gate in the east end of the north wall, Robert of Flanders’ men took up a position opposite St. Stephen’s Gate in the middle of the north wall, and Godfrey of Boulogne’s troops pitched their tents opposite the New Gate on the west end of the north wall. The southern Franks, under Raymond of Saint-Gilles, bivouacked on Mount Zion opposite the gate of the same name. This was the only position south of the city where a siege tower might be rolled up to the wall.

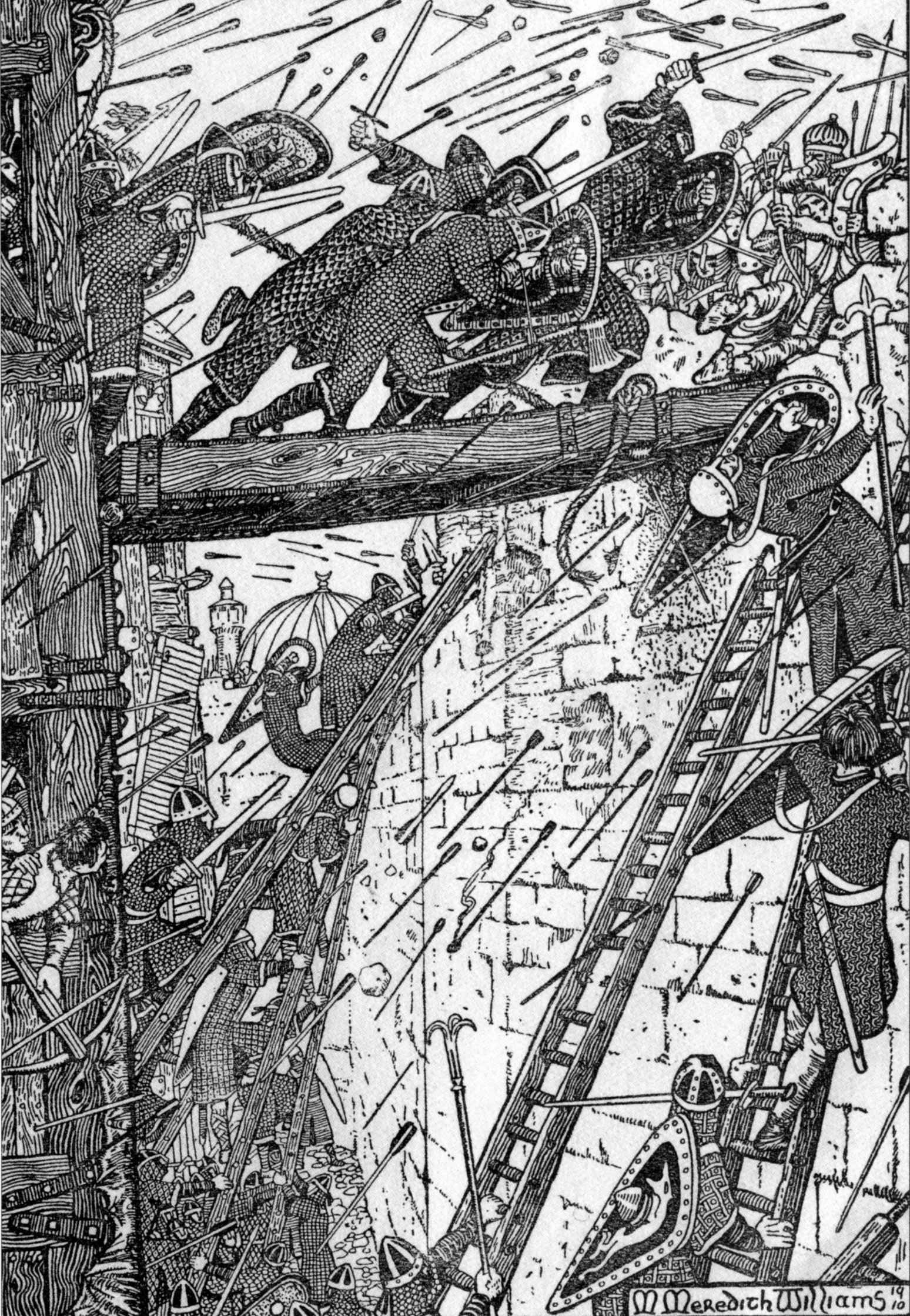

On June 13, the Franks launched a desperate attack against the city that failed because they lacked sufficient siege equipment, such as ladders, mangonels, and siege towers. “In morning’s light … they rushed upon the city from all sides in an astonishing attack,” wrote Fulcher of Chartres. “But when they … were unable to enter by means of the scaling ladders because there were few of them, they sadly abandoned the assault.” The Franks suffered substantial casualties from arrows, as well as from rocks that were hurled at them from the defenders on the ramparts. Nevertheless, they managed to capture the outer works along the northern wall so that the effort was not completely without gain.

A great piece of good fortune came the Franks’ way on June 17 when six ships from the West arrived at Jaffa. All but one, it seems, were stuck at Jaffa as a result of the arrival of a hostile Egyptian fleet that blockaded the port. The ships had extra stores of construction supplies, including ropes, hammers, and nails that the crusaders could use to build ladders, mangonels, battering rams, and siege towers.

Upon learning that the squadron of ships had arrived, Raymond of Saint-Gilles had ordered Count Galdemar Carpenel to lead a band of 20 knights and 50 foot soldiers to Jaffa and retrieve the supplies. While the band of southern Franks was passing through Ramla, it was ambushed by a force of 600 Fatimid horse archers reconnoitering from Egyptian-held Ascalon. “Galdemar, because of the small number of his men, arranged his knights and bowmen in the front ranks and, trusting in the Lord, advanced upon the enemy without hesitation,” wrote Raymond of Aguilers.

As seemingly fast as the desert wind, the Arab horsemen encircled Galdemar’s band, softening them up with arrows. Just when it seemed as if they might be annihilated, another crusader band of 50 knights led by Raymond Piletus came to their rescue. Piletus’ heavy cavalry charged the lighter Arab cavalry, inflicting heavy losses and driving them off. Galdemar lost four knights and nearly all of his foot soldiers, and the Egyptians lost about 200 of their cavalry. The crusaders continued to Jaffa. They helped the sailors dismantle their ships and haul the wood back to Jerusalem to use in the construction of siege equipment. Meanwhile, Robert of Flanders and Tancred led a separate expedition to Samaria, where their foraging party harvested additional wood to use in the construction of the siege apparatus.

Over the next several weeks the crusaders worked tirelessly to construct multiple siege ladders and mangonels. Because they required so much wood, the Franks built only two siege towers. The northern Franks built one, and the southern Franks built the other. The wheeled siege towers included a mangonel for close support and were covered in hides to protect the men inside from arrows, stones, and Greek fire. The engineers built the towers higher than the city’s battlements so that archers and crossbowmen could shoot down on the defenders. “When the Saracens saw our men engaged in this work, they greatly strengthened the fortifications of the city and increased the heights of the turrets at night,” wrote the anonymous historian of the Geste Francorum.

On July 6, the princes leading the crusade decided to conduct the penitential procession and scheduled it for July 8. After it was concluded, they made final preparations for an all-out assault on the city before the Egyptian relief army arrived. Godfrey’s men had constructed their tower “from small pieces of wood, because large pieces could not be secured” in Palestine, wrote Fulcher of Chartres. The tower was carried in pieces and assembled first near the New Gate on the northwest corner of the city near the Quadrangular Tower. But when they realized that Herod’s Gate on the opposite end of the north wall was less strongly defended, they moved it to that sector during the night of July 9-10. Before they could roll it against the wall, though, they had to fill in a large ditch in front of the main wall with dirt and rubble. The northern Franks used rubble from the outer wall previously destroyed to fill in the ditch while taking fire from the Sudanese archers on the battlements. Raymond of Saint-Gilles’ men were involved in a similar task, filling in a ditch near the Zion Gate on the opposite side of the city. Raymond’s men apparently were less motivated, and he paid them for the rocks that they carried. On July 14, the Franks made good progress toward gaining access to the city with a battering ram. Final preparations were made for a full-scale attack the following day.

Godfrey and his captains assembled their men at dawn on July 15. Loud trumpets blaring in the pink dawn announced a general attack. The men rolled the breaching tower into the same place where the battering ram was close to forcing a breach in the wall. Having grown impatient with the battering ram, the duke ordered it burned. Godfrey also ordered his men to set fire to the bales of cotton and hay that the defenders had hung over the walls to prevent siege artillery from causing catastrophic damage. A wind from the northeast favored the crusaders and carried the smoke from the combustibles into the eyes of the defenders, temporarily blinding them.

The duke then ordered his engineers to “diligently draw up two pieces of timber that had fallen down from the wall,” wrote crusader historian William of Tyre. “Then he commanded that the side of the [tower] that could be lowered should be let down upon the two pieces of timber.” The Egyptians had placed the timber along the top of the wall to repair damage made by the crusaders’ mangonels, but the beams had fallen to the ground. The platform resting on the timbers formed a stable bridge for the Franks to run onto the battlements.

With archers on the top of the tower firing down onto the battlements, Godfrey and his brother Eustace, as well as two other brothers from Tournai, Ludolf and Gilbert, led their men onto the walls. While the main attack was directed against the top of the wall, other Franks were able to break into the city through a small breach made by the battering ram. As soon as Godfrey’s men had captured a section of the wall, the duke’s banner was planted on it for all to see. Some of the men that Godfrey and his captains had led onto the wall ran west to secure St. Stephen’s Gate, which they opened to allow large numbers of northern Franks into the city.

The defenders fled to the strongpoints, such as the Tower of David and the temple area. “Our men followed and pursued them, killing and hacking, as far as the temple of Solomon, and there was such a slaughter that our men were up to their ankles in the enemy’s blood,” wrote the author of the Geste Francorum. Additionally, some of the northern Franks rushed to the southwest corner and attacked from behind the Muslims defending the wall in the southwest corner of the city against the southern Franks. The southern Franks were having great difficulty reducing opposition because the Egyptians had deployed the majority of their magonels to support the Zion Gate. When they learned that Godfrey’s troops had fought their way into the city, the southern Franks rushed the walls near the Zion Gate with ladders and climbing ropes. When the Egyptians defending the Zion Gate were attacked from behind, they retreated to the Tower of David. The attack was over by late morning, and Raymond negotiated a surrender of the city with the Egyptians in the Tower of David. Under the terms, the surviving Egyptians and Sudanese were allowed to march out of the city. What occurred afterward was a brutal sack of the city in which all but Christians were slain.

With drawn swords, relates Fulcher of Chartres, the Franks rampaged through the city. They gathered up gold and silver, livestock, and all manner of precious items belonging to the Muslims. On the morning of the second day, according to the author of the Geste Francorum, “our men cautiously went up to the roof of the Temple and attacked Saracen men and women, beheading them with naked swords.” Some of the Saracens, however, leaped from the Temple roof.

In the days that followed, the crusaders offered to crown Godfrey as king of the crusader state of Jerusalem. Believing that it was wrong to wear a crown in the same city where Jesus had worn a crown of thorns, Godfrey instead accepted the title Defender of the Holy Sepulcher. Godfrey and the other princes decided to march 50 miles to Ascalon to meet the Fatimid relief army on open ground rather than at Jerusalem.

Tancred, who had been sent on July 25 with Eustace of Boulogne to assert Frankish control over Nablus to the north, skirmished with Fatimid cavalry on August 7. Upon learning of this clash, Godfrey and Robert of Flanders set out immediately to support him. They were joined at Ramla on August 10 by Raymond of Saint-Gilles and Robert of Normandy. The approximately 10,000-strong crusader army marched to Ascalon in square formation so that it could face an attack from any direction, or more than one direction, if circumstances called for it. On August 12, the crusades attacked the Fatimid camp north of the walled city.

The Fatimid army numbered about 20,000, but not all of it was bivouacked outside the north wall of the city. The Fatimid foot soldiers outside the city formed up for battle. The Fatimid attack began in earnest when Ethiopians armed with flails attacked the center of the Frankish line. The flails were highly effective and were able to inflict casualties on the Frankish footsoldiers. The Ethiopians were supported by missile troops, including archers, spearmen, and slingers. Godfrey, on the left of the Christian line, had wisely refused his flank. As a result, he was able to block an attempt by the Arab cavalry to get behind the Franks.

The momentum switched to the Franks when the crusader knights charged the Fatimid infantry. The Franks overran the Fatimid camp, and some began plundering it. The Fatimid officers attempted to rally their men, but the effort was in vain. The Fatimid troops attempted to withdraw inside the walled city, but the garrison closed the gates for fear the Franks would get inside. Raymond and Godfrey bickered over who should be in charge of negotiations for the city’s surrender, which derailed the negotiations. As a result, the Franks returned to Jerusalem.

In the weeks that followed, many of the warrior-pilgrims departed by boat for their homes. Godfrey was left with only 300 knights and 2,000 footsoldiers to hold off Fatimids, Arabs, and Turks. Because of the vast odds he faced, it was a miracle that the Kingdom of Jerusalem was able to survive in its infancy.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments