By David Michlovitz

Despite never having gained the mythological fame of Valley Forge, the encampment of the Continental Army at Morristown, New Jersey, over the winter of 1779-80 was a horrendous trial, worse for the men than that at the Pennsylvania hollow, and dire for the revolutionary cause. General Washington again had to preserve his army through extreme cold, desertion, starvation, and mutiny.

As winter approached and the year’s campaigning came to a close in 1779, Washington began the search for suitable places to winter his forces. In a letter to Horatio Gates on November 17, he wrote:

“It now remains to put the Army in such a chain of winter Cantonments as will give security to these posts, and to take a position with the remainder which will afford Forage and Sustinence, and which will at the same time preserve us from the insults of the collected force of the enemy; these several matters are now in contemplation, and until they are determined, you will be pleased to halt your troops at Danbury.”

Smaller detachments of the army were stationed at West Point and other strategic locations in New York and New Jersey. In addition to guarding important points from which to monitor British moves, distributing the Continental Army meant that one area would not be completely depleted of its foodstuffs and forage. Washington informed Gates of his choices in a letter the next day in which he indicated that “the main Army (from whence detachments will be made towards the No. River and Staten Island) will lay on the heights some where back of the Scots plain.”

The area Washington was referring to was not yet specific, but in the vicinity of Morristown, where the army had spent the winter of 1776-77 following the critical victories at Trenton and Princeton. Morristown was an ideal location for a variety of reasons. To the southeast were the Watchung Mountains and the Great Swamp, making the position ideal for defense. To the north were the important iron works at Mt. Hope, Hibernia, and Ringwood needed to supply the army. Most important of all, the town was well suited as a hub from which to deploy forces to the towns near the British outposts on Staten Island, notably Perth Amboy, Woodbridge, Rahway, and Elizabethtown.

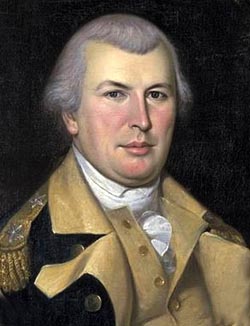

The officer in charge of selecting the exact location, Quartermaster Nathaniel Greene, was unsure of possible British moves, and had some difficulty making a final decision. Washington hurried Greene along, writing on November 23 that: “We must make conveniency give way to necessity,” and instructed him to direct the troops to that area with the best supply of wood, water, and dry ground.

The final location was selected by the Commander-in-Chief himself on his way from West Point to Morristown on November 30. Washington figured that in light of his plan to send the Southern regiments as reinforcements to South Carolina, and with the large number of troops whose enlistment period would soon expire, it “will oblige us to seek a more remote position than we otherwise would have done.”

The place chosen for the troops would not be Scotch Plains, but a nearby hilly region between Morristown and Mendham, roughly three miles southwest of the former. On Friday, December 3, the General Orders for the day instructed the officers to exert themselves in getting their men to construct huts in this place that were to be torn down if they did not comply with specifications. Special warning was made to keep soldiers from tearing down the fences or enclosures of the local inhabitants. Such offenses were to be seriously punished.

Despite the order, many of the Continentals were still en route to their cantonment sites. Slowing their progress were two feet of snow and bitterly cold weather. Moreover, shoes had been in very short supply and some men went without during the march. Others were described as being “almost naked.” Wagons were also at a premium, requiring that heavy baggage such as tents lag a number of days behind their regiments.

The first night the men spent at Morristown brought little relief from the day’s sufferings. The only protection against the chilling wind was brushwood thrown together. The frozen ground served as a bed for the exhausted and hungry patriots. According to Dr. James Thatcher of Colonel Henry Jackson’s Additional Regiment (troops from the Boston area), the mounted officers fared a bit better. Usually they had a horse blanket on hand, along with their greatcoats to wrap themselves in. After removing the snow from a site, five or six officers would lay down side by side with fires at their feet. Attendants were ordered to keep these stoked during the night.

A Deprived Army Fueled Only By Its Patriotism

The situation improved slightly with the arrival of tents, and work commenced on the log huts constructed with the good supply of oak and walnut at hand. Still, things remained difficult. The tents were a struggle to erect because the ground was frozen, and only by maintaining large fires could the soldiers keep themselves from freezing.

Adding to the suffering were empty stomachs. The entire army went seven or eight days without any substantial food. The usual fare consisted of fresh beef; no salt, bread, or vegetables were available. Even the horses were not spared the misery. With no fodder to be had, they went, according to Dr. Thatcher, 24 hours without any food save the bark peeled from the trees they were tied to. In his journal, Thatcher vented his anger and frustration:

“It is a circumstance greatly to be depreciated that the army, who are devoting their lives, and every thing dear to the defense of our country’s freedom, should be subjected to such unparalleled privations, while in the midst of a country abounding in every kind of provisions. The time has occurred before when the army was on the point of dissolution for the want of provisions, and it is to be ascribed their patriotism, and sense of honor and duty, that they have not long abandoned the cause of their country.”

One of the reasons provisions could not be acquired was the rapid depreciation of the continental currency issued by the Continental Congress. The local farmers were unwilling to sell their produce for such payment that, by December of 1779, was being traded at the rate of 30 for one dollar’s worth of coin.

Adding insult to injury was the news of the failure of a combined Franco-American assault on the city of Savannah, Geo., and worse, yet more snow. Further efforts had been made to improve the shelters, and straw was issued for the men to sleep upon. In addition to straw, the officers had large marquee tents with stone chimneys constructed at an opening in the end.

Overbearing Hunger Amidst a Tremendous Blizzard

Such lodgings were of no use on January 3, 1780, however. A blizzard of tremendous magnitude descended upon New Jersey. “No man could endure its violence without danger of his life,” Thatcher recorded. Officers’ marquees were torn apart by the violent winds, and some of the soldiers, in their small tents, were completely covered under the snow. The white blanket, up to six feet deep, further complicated the already-critical supply situation. In fact, this was the worst winter of six of the American Revolution, the worst even in living memory. “For the last ten days we have received but two pounds of meat per man, and we are frequently for six or eight days without meat, and then as long without bread,” Thatcher wrote some days following the great storm. He went on to note how it was common knowledge that General Washington knew what his troops were enduring, and he admired the fact that they were conducting themselves with great patience and fortitude under such horrid circumstances. The men were so pained by their hunger and lack of shoes that routine camp duties were a struggle, let alone the construction of huts.

Washington was indeed concerned, and had been for some time, as noted in a letter to Congress of December 15 in which he informed it that the prospects for his force were as bad as they had ever been during the entire war. He predicted the dissolution of the army for want of subsistence if a solution was not immediately found. The general then submitted his own idea: to solicit a loan of four or five thousand barrels of provisions from a collection of some 20 thousand then in Maryland. These were awaiting the use of the French Army and fleet (who could, of course, pay for them in hard currency).

Until this move could be effected, Washington would be forced to garner what he could from the surrounding countryside. The following day, Washington sent a message to the governors of New York, New Jersey, and Maryland and to Presidents Reed of Pennsylvania and Rodney of Delaware. It called upon them to have their states assist in procuring supplies to save the army from disbanding.

Washington was also imploring James Wilkinson, the Clothier-General, to make every effort to bring clothing to the ragged army, and for Nathanael Greene to provide enough transport to do so. By Christmas Eve, Washington informed Congress that the situation was such that Indian corn, intended for horse feed, had been ground up to make flour for the men.

Private Joseph Plumb Martin of the 8th Connecticut Regiment recalled another occasion when he and his colleagues had to dine on such fine stuff: “Our Connecticut Yankees were as ignorant of making this meal or flour into bread as a wild Indian would be of making pound cake. All we had any idea of doing with it was to make it into hasty pudding, and sometimes, though rarely, we would get a chance to get a little milk or a little cider, or some such thing to wash it down with; and when we could get nothing to qualify it, we ate it as it was. Indian flour was much worse than meal, being so clammy as glue, and as insipid as starch. We were glad to get even this for nothing else was to be had.”

Discipline was becoming more difficult to maintain because the patience of the troops began to falter in the face of the continued cold and starvation. It was not long before the troops reverted to a course of action taken by armies for thousands of years: plundering the local inhabitants. Washington soon received numerous complaints from nearby residents that their poultry, sheep, pigs, and even cattle were disappearing from their farms. Desertion was also on the rise.

The Commander-in-Chief was resolved not to allow either of these offenses to continue, and such infractions were punished severely. Orders were given to record those missing from their huts at night to be brought to immediate trial. Courts-martial were convened and harsh penalties dealt out. The usual punishment was a severe whipping; up to a hundred lashes was not uncommon. In some cases, offenders were hanged. Despite all of this, Washington was sympathetic of the conditions his men suffered, and was notorious for granting pardons, especially for those sentenced to death. The following was in his General Orders for February 24:

“The frequent occasions the General takes to pardon, where strict justice would compel him to punish, ought to operate on the gratitude of offenders to the improvement of their morals.”

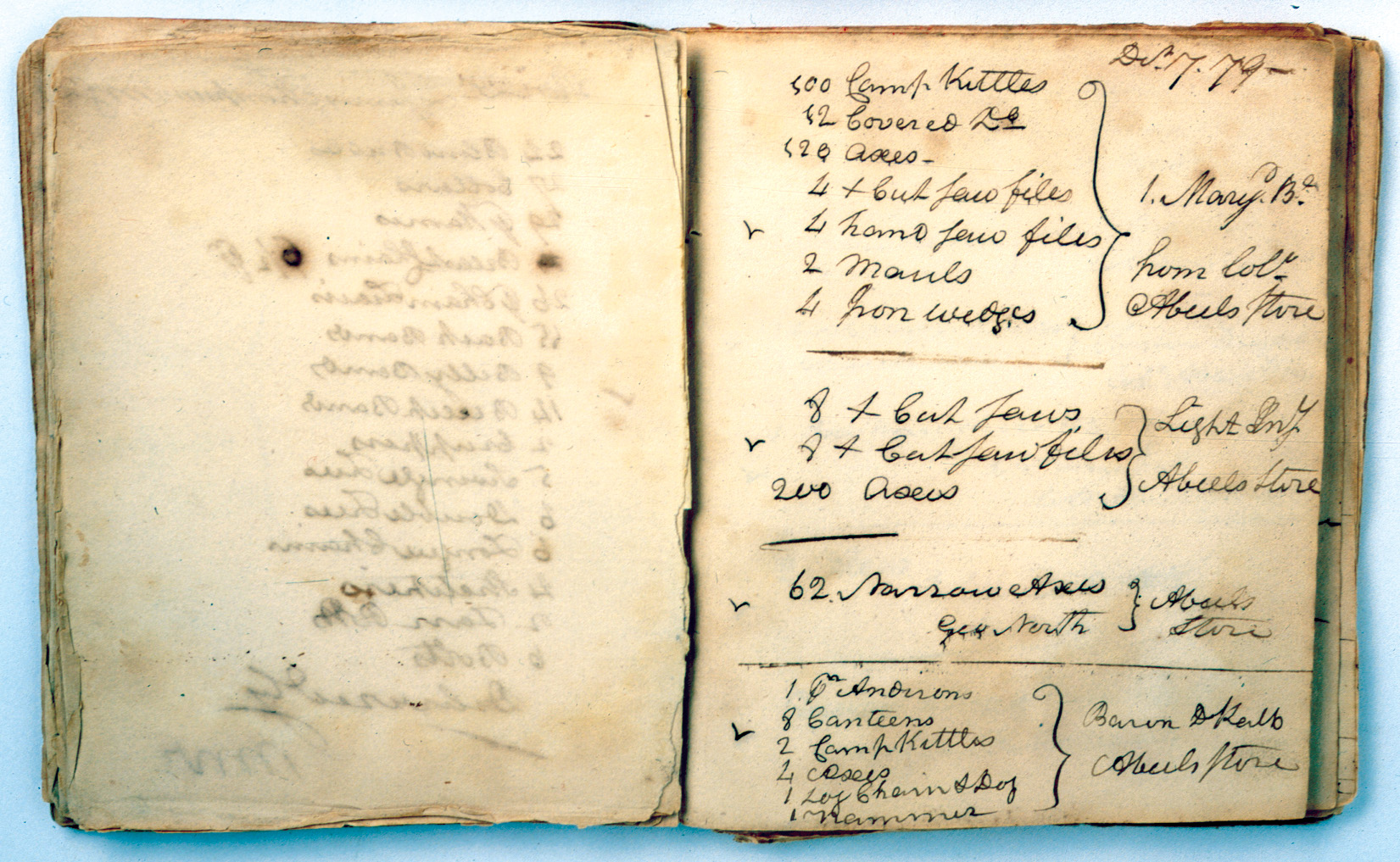

On January 8, in a move that probably saved the Continentals from complete disaster, Washington instructed officers of the army stationed at various counties of the state to ask local magistrates for assistance in procuring foodstuffs. Washington had asked these officials to comply with the request, figuring it would be less offensive toward the local inhabitants.

The officers were to designate a place for collection of grain and cattle. There, in conjunction with the local officials, they were to weigh what was brought in and issue appropriate certificates of payment. These certificates were essentially IOUs with the recipient given the choice of requesting eventual payment at the current market price, or at the time payment would be received.

If the farmers should reject these terms Washington ordered that: “In case of refusal you will begin to impress till you make up the quantity required. This you will do with as much tenderness as possible to the Inhabitants, having regard to the stock of each individual, that no family may be deprived of its necessary subsistence. Milch cows are not to be included in the impress.”

This endeavor brought the needed relief. In his journal, Dr. Thatcher noted that “this expedient had been attended with the happiest success.” An ample amount of supplies arrived just in time to save the army from destruction. Miraculously, many of the men whose enlistments were to run out decided to stay for the duration of the war. Washington was finally able to send favorable tidings to Congress. “I now have the pleasure to inform Congress that the situation of the Army at present has been for some days past, comfortable and easy on the score of provision,” he wrote.

Contact with the enemy did not end completely with the arrival of winter. Numerous raids and small skirmishes occurred on the snow-covered fields of the Jerseys, as the territory was then known. While the supply situation was being rectified, Washington was toying with the idea of taking advantage of the cold weather. Viewed up to that point as only adding to the misery, the extreme low temperatures had formed ice on the inland water bodies, providing a natural bridge upon which to raid the British outpost on Staten Island. With luck, Washington could effect another success as he did at Trenton in December 1776.

Washington chose Maj. Gen. William Alexander “Lord Stirling” to lead the attacking force. “The objects in view are to captivate the Troops on the Island and to bring off or destroy all public stores of every kind, and fat Cattle and sheep, if time and circumstances allow,” the Commander-in-Chief instructed.

According to the intelligence then available to Washington, the British garrison on Staten Island did not exceed a thousand men, the majority manning redoubts at “Watering Place,” two hundred of the Queen’s Rangers at Richmond, and Buskirk’s Regiment of a hundred at Deckers. Despite telling Stirling that “to point out any precise plan of operation would be wrong in me,”

Washington went on to give “my present ideas of the several matters which appear to me worthy of your Lordship’s attention:

“To get on the Island without discovery is so essentially necessary, that the complete success of the enterprise depends absolutely on it. Every device and Stratagem therefore should be used to effect it by eluding or seizing their Guards or patrols and deceiving their Spies on this side.

“… It is not likely that any number of prisoners will be taken unless the Redoubts at Watering place are possessed very early by us and, as I take for granted that they can only be taken by surprise, I would propose the following mode of effecting it. The main body to cross at Tremly’s point on the account of the goodness of the Ice, and because it seems an unsuspecting place, and march immediately to the Cross Roads at Mereraus, continuing on the middle Road, providing the Enemy have not taken the alarm; in that case I deem it would be fruitless. The parties of 100 men, if not interrupted, are to advance each to a redoubt and endeavor to surprise it, before it can be reinforced. If they succeed they can with ease hold the Works until the support comes up.

“… An officer in who’s diligence you can confide, should reconnoitre the crossing place before night and make observations on the opposite shore. He should cross with a party of 15 or 20 chosen Men at least half an hour before the Column moves down, having sent forward two or three trusty Men to see that the coast is clear, he should follow his party and so dispose of them as to seize any patrols or suspicious person. Some of Webb’s Men clothed in Red would be best for this duty and to be always in the advance.

“Every Officer should have a Roll of the platoon he commands and see that no Man absents himself; the most profound silence should be observed under pain of instant death.

“White Cockades or some Badge of distinction should be worn by our Officers and Men and the Watch word should be such as to deceive the Enemy, for instance ‘Clinton,’ ‘Cornwallis,’ ‘Skinner,’ ect. ect.

“There should be no firing if it is possible to avoid it in the several attacks. The Bayonet will be found the most effectual weapon, especially in the night.”

Some five hundred sleighs were dragged along by the force of over 2,500 men to their objective, passing over the ice near Elizabethtown. They prepared for their raid on the cold night of January 14. But the British were prepared, “doubtless by some Tory,” Joseph Plumb Martin, a member of the expedition, concluded. Subsequently the enemy works were deemed too strong to storm, and the attack was called off. Moreover, the ice was not as solid as expected.

Martin and his companions spent the night on a bleak hill, exposed to the northwest wind without shelter. They used an old rotten fence dug out of four feet of snow for fuel. In the morning, some American artillery opened up on an armed British brig in the nearby ice, and then the American Patriots began their retreat.

Unhappily they were pursued by the British who managed to capture several of them. The force returned exhausted and frostbitten with only some tents, arms, baggage, several casks of wine on the sleds, and 17 prisoners to show for their efforts. Six Continentals were killed and five hundred “slightly frozen.”

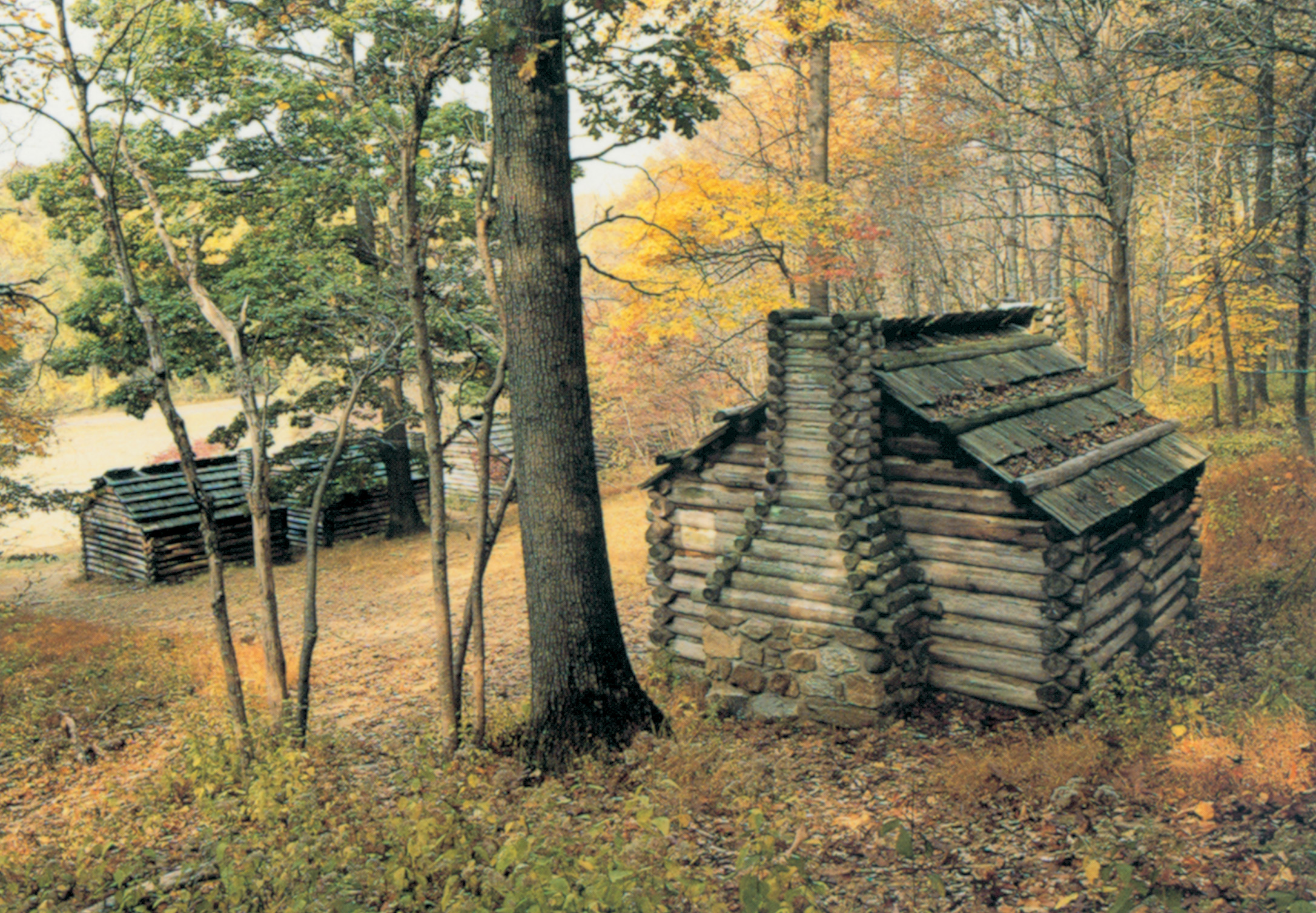

Sometime shortly after the failed raid, the Americans completed their huts. Each was made to be 12-by-16 feet and arranged in rows by regiment and brigade. In his memoirs of the war, Private Joseph Plumb Martin described their construction:

“The next thing is the erecting of huts. They were generally about twelve by fifteen or sixteen foot square, all uniformly of the same dimensions. The building of them was thus: after procuring the most suitable timber for the business, it was laid up by notching them at the four corners. When arrived at the proper height, about seven feet, the two end sticks which held those that served for plates were made to jut out of about a foot from the sides, and a straight pole made to rest on them parallel to the plates; the gable ends were then formed by laying on pieces with straight poles on each, which served as a ribs to hold the covering, drawing in gradually to the ridgepole. Now for the covering: this was done by sawing some of the larger trees into cuts about four feet in length, splitting them into bolts, and riving them into shingles, or rather staves; the covering then commenced by laying on those staves, resting the lower ends on the poles by the plates; they were laid on in two thicknesses, carefully breaking joints. These were then bound on by a straight pole with witches, then another double tier with the butts resting on this pole and bound on as before, and so on to the end of the chapter. A chimney was then built at the center of the back side, composed of stone as high as the eaves and finished with sticks and clay, if clay was to be had, if not with mud. The last thing was to hew stuff and build up cabins or berths to sleep in, and then the buildings were fitted for the reception of gentleman soldiers, with all the rich and gay furniture.”

It was in these that the troops would spend the majority of the winter and on into the spring, though detachments were frequently sent to stay in towns nearest the British post on Staten Island.

Martin’s regiment was sent on one such detail to patrol against loyalists and British raids between Elizabethtown and Woodbridge during the early spring. When they returned to the Morristown cantonment in late May, the food stores were once again in crisis. Washington wrote to Congress that “I am once again under great apprehensions on the score of our Provision supplies.”

Once again left with the pain of hunger, the patience of Martin’s regiment and others in the Connecticut line wore out on the evening of May 25. They expected their fare to greatly improve upon returning to the main encampment (they ate the Indian meal referred to above during their detached duty), but instead received “a little musty bread and a little beef every other day … and then nothing at all.”

Starving Troops Drill In Defiance

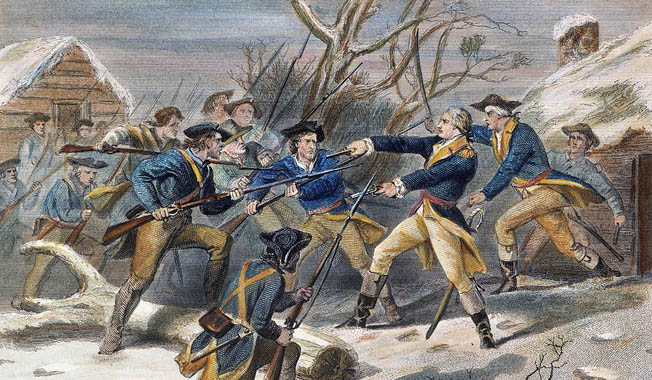

Trouble began during the following evening roll call during which the soldiers snapped back at their superiors and openly refused to obey orders. An argument between the 8th Regiment’s adjutant and a soldier prompted the private to call to his comrades, “Who will parade with me?” The entire regiment fell into line and formed upon the parade ground and was soon joined by their neighbors, the 4th Connecticut Regiment. In order to avoid any leader being singled out for a court-martial, commands were given silently to the drummers who rattled off the signals to shoulder arms, about face, and march, which they did to the music of their fifes and drums.

But the officers soon realized what was going on, and by running through some bushes and across a brook, beat their troops to the nearby encampment of the 3rd and 6th Connecticut Regiments. There, in the descending darkness, the officers commanded those men to parade without arms. Shortly afterwards Colonel Meigs of the 6th Regiment was wounded by a bayonet thrust while trying to keep his troops from obtaining their muskets.

Having failed to spread the revolt to their fellow brigade members, the two insubordinate regiments returned to their own parade with the officers walking behind. When one soldier in the rear forgot himself and called out “Halt ahead” he was dragged out of line by a group of officers to be made an example of, only to be surrendered back to his companions at bayonet point. Attempts by their officers to disperse them got nowhere, as did a poor attempt by one officer to convince them that a drove of cattle had arrived for their consumption.

While this drama was playing out, the Pennsylvania Line (which would itself mutiny while detached to Morristown the following year) was ordered under arms and marched to their campsite for what they were told was a secret mission. Unbeknown to the men of these Pennsylvania regiments, they were being positioned in an effort to surround the Connecticut mutineers. Word of the true meaning of the mission soon spread, and before long cries were shouted out, “Let us join the Yankees; they are good fellows, and have no notion of lying here like fools and dying!” Upon hearing such utterances, the officers had second thoughts and ordered their troops back to quarters.

As Martin recalled, the mutiny fizzled out peaceably, and no attempt was made by the men to return home: “After our officer had left us to our own option, we dispersed to our huts and laid down our arms on our own accord, but the worm of hunger gnawing so keen kept us from being entirely quiet. We therefore still kept on the parade in groups, venting our spleen at our country and government, then at our officers, then at ourselves for our imbecility in staying there and starving in detail for an ungrateful people who did not care what became of us, so they could enjoy themselves while we are keeping the cruel enemy from them.”

The mutiny effected some results. Martin wrote that “Our stir did us some good in the end for we had provisions directly and no great cause for complaint for some time.”

Washington was of course greatly concerned by the mutiny event and used it to once again beg Congress for money and food. “From this detail Congress will see how distressing the situation is.”

Quartermaster General Nathanael Greene wrote to Governor William Greene of Rhode Island (a distant relative of his) on the matter: “Our distress is beyond description, and without more attention is paid to the Army, there will be none many weeks longer. Mutinies have already taken place in the Connecticut line, and we are apprehensive it will run through the whole line like wild fire. We have been starving here for this three weeks past, and have but poor prospects before us at this time.”

The Morristown Encampment Prepared the Army For Major Victories

The encampment broke up in early June when a British force landed in New Jersey and the new season of campaigning began.

In fact, the last major engagements of the war in the North would take place at the nearby towns of Connecticut Farms on June 7 and Springfield on June 23, demonstrating yet another effect of the terrible winter and its privations. In these last engagements, troops that had survived the hard winter at Morristown distinguished themselves. They repelled five thousand enemy under the command of General Baron Wilhelm von Knyphausen, commander of New York during Sir Henry Clinton’s campaign against Charleston, S.C.

Even more mettle may have been forged at Morristown in that dreadful season. Nathanael Greene, for whom much credit goes for the army’s survival, was sent south to take over the shattered remnants of the Southern Army. His famous campaign is credited with bringing about the siege of Yorktown in October 1781.

The trial of Morristown during the cruel winter of 1779-80 demonstrates Washington’s greatest achievement: keeping the army in existence for the duration of a long war under incredibly difficult circumstances. Indeed it is argued that Washington’s ability to keep at least some semblance of an army in the field was as important a victory as any battle. Washington’s resolve during such desperate hours kept the Continental Army together long enough to continue to receive the direct aid of French troops (even after the failures at Savannah and Newport) and ultimate victory.

This horrible winter and its privations also prove how stalwart were the soldiers of the Continental Army. Despite sleeping shoeless in snow, enduring blizzards without shelter, suffering starvation rations and more, they were determined to carry on. All hope of a true independence from Great Britain would have been dashed had the underpaid, underfed, unprofessional soldiers given up on what enough of them felt was a noble struggle worthy of almost every sacrifice.

Why is this not taught to everyone?