By Flint Whitlock

The island of Sicily, lying in the Mediterranean Sea between Tunisia and the toe of the Italian peninsula, is no stranger to war and conquest. Over the centuries, because of its strategic location, Sicily has been invaded, fought over, occupied, and ruled by the ancient Greeks, Romans, Carthaginians, Vandals, Ostrogoths, Byzantines, Saracens, Normans, Germans, French, Spanish, Austrians, and the Bourbon Kingdom of the two Sicilies.

The most recent conflict took place in the summer of 1943. The island was home to some 365,000 heavily armed Italian and German soldiers who were anticipating that the Americans and British, who had just been victorious in North Africa, were about to invade. They were right.

Both the Italian and German forces on Sicily were commanded by General Alfredo Guzzoni and consisted of the Italian Sixth Army and the German Hermann Göring Panzer Division and 15th Panzergrenadier Division.

The Allied high command had determined that keeping a sizable number of enemy troops tied up in the Mediterranean was important because preparations were being made to invade northern France in an operation called Overlord, and the farther these enemy troops were from France, the better.

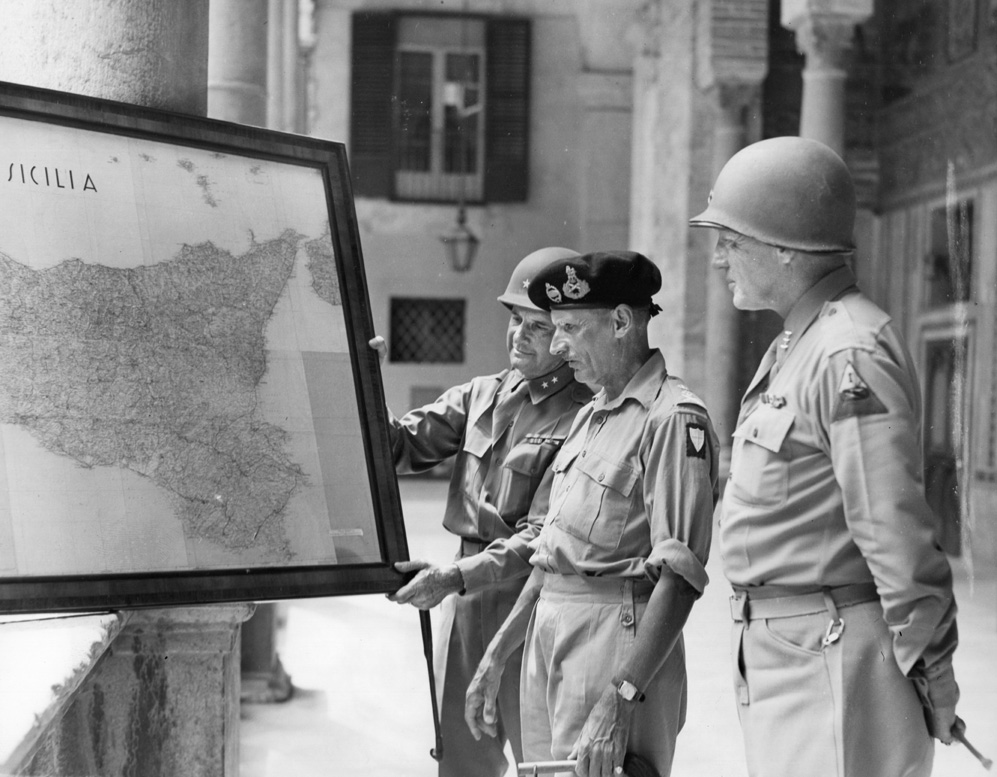

Therefore, it was decided to mount a major airborne and amphibious invasion of the 9,926-square-mile island with both American and British troops. For this operation, code named Husky, the Allies would employ 181,000 men, 3,200 ships, and 4,000 aircraft. Named to command the entire operation was Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had also been in charge of the successful Operation Torch landings in North Africa the previous November. Ike’s deputy commander was British General Sir Harold Alexander.

The British contingent was made up of General Sir Bernard Law Montgomery’s Eighth Army and included the 5th, 50th, 51st, and 1st Canadian Infantry Divisions, plus the 1st Airborne Division, 1st Air Landing Brigade, and a detachment of Commandos. The British force was split between Lt. Gen. Sir Miles Dempsey’s XIII Corps and Lt. Gen. Sir Oliver Leese’s XXX Corps.

The American Seventh Army was commanded by Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., and comprised the 1st, 3rd, and 45th Infantry Divisions, along with a regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division under the operational control of Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes’s II Corps. The 2nd Armored Division was the “floating reserve,” and the 9th Infantry Division would remain in North Africa and be brought in if needed.

Two naval task forces, under the command of Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, supported the invasion. The Eastern Naval Task Force was made up of assets from Admiral Bertram Ramsey’s British Mediterranean Fleet, while the Western Task Force, with ships of the U.S. Eighth Fleet, was commanded by Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt.

Montgomery’s forces would land on the southeast corner of the triangle-shaped island, with Patton’s men hitting the beaches to the west, in the Gulf of Gela. Initial intelligence said that the island was garrisoned by eight or 10 divisions of the Italian Sixth Army—half of which were rated as second-class troops—and some 40,000 Germans positioned mostly around Palermo in the north and the major airfields.

Montgomery, the hero of Alamein, was worried about the coming invasion. The night before it began, he wrote in his diary, “I am under no illusions as to the stern fight that lies ahead.” He had reason to worry.

Before embarking from North African ports, Patton sent an inspirational message to the men of his new Seventh Army: “When we land, we will meet German and Italian soldiers whom it is our honor and privilege to attack and destroy…. The glory of American arms, the honor of our country, the future of the whole world rests in your individual hands. See to it that you are worthy of this great trust. God is with us. We shall win.”

Colonel James Gavin, the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment’s commander, also sent a message to his troops that read in part, “The term ‘American Parachutist’ has become synonymous with courage of a high order. Let us carry the fight to the enemy and make the American Parachutist feared and respected through all his ranks. Attack violently. Destroy him wherever found. I know you will do your job. Good landings, good fight, and good luck.”

Husky began inauspiciously at midnight on July 9/10 with a disastrous British glider assault on Syracuse. The plans had called for 128 men of the 1st Air Landing Brigade to land in six Horsa gliders, grab the Ponte Grande bridge that crossed the Anapo River southwest of Syracuse, and hold it until relieved by the 5th Infantry Division, coming ashore by boat at Cassibile, seven miles to the south.

Before dawn, 137 CG-4A Waco gliders carrying a total of nearly 1,800 men were on their way to Syracuse. Unfortunately, many of the pilots of the C-47 tow-planes and gliders were barely trained, and the heavy winds that morning were wreaking havoc on formation flying. To make matters worse, antiaircraft gunners were on the alert and began peppering the incoming aircraft with flak.

The result was chaos. Some gliders were shot out of the sky, while others, frantically maneuvering to avoid the flak, smashed into other gliders. At least 69 Wacos crashed into the sea, drowning more than 250 men. Most of the gliders that actually landed were scattered over 25 miles; only 12 of the 147 CG-4As landed anywhere near their assigned landing zones.

The plan called for the glidermen to be quickly reinforced by troops coming overland. A platoon from the South Staffordshire’s 2nd Battalion managed to reach the Ponte Grande and held off several enemy counterattacks before additional Italian troops arrived and attacked the invaders. Low on ammunition, most of the British troops were forced to surrender. Luckily, the rest of the British seaborne invasion went much more smoothly and the troops began overcoming resistance around Syracuse.

The U.S. 1st Infantry Division, riding in landing craft through a pounding surf, hit the beaches at Gela in the dark. Fortunately, the coastal defenses were manned by less than stalwart Italian forces, and so the Big Red One’s landings went relatively easily. The Italians put up only token resistance before either surrendering or retreating.

Lieutenant Leonard E. Jones of Company C, 18th Infantry Regiment laughed: “Italians are the worst soldiers on the face of the earth—they love to be captured.”

Major General Lucian Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division came ashore before dawn in rough seas around the coastal town of Licata. As the landing craft bounced in the swells toward shore, powerful searchlights from land lit up the darkness. For unknown reasons, the enemy did not fire and the lights were switched off.

The worrying silence was soon broken by scattered fire, but it was not terribly heavy or effective, and the 3rd Division, attached Ranger battalions, and supporting tanks were all ashore before 5 am. Seven hours later, the airfield, town of Licata, and port were in American hands.

Truscott later wrote, “All beach resistance had been smothered by the speed and violence of the assault and more than 2,000 prisoners were taken. Our casualties were little more than a hundred.”

During its first-ever combat action, Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton’s 45th Division (the Oklahoma and Colorado National Guard, nicknamed the “Thunderbirds”) was finding success elusive at the Scoglitti beachhead; on the run in, two landing craft crashed into each other, capsized, and 38 men drowned. At 4:30 am, enemy aircraft tried attacking the seaborne troops, but a flight of British Spitfires chased them off.

Other landing craft struck rocks or sandbars or their troops were released in too-deep water, and the men drowned without ever having fired a shot. Once on shore, the men of the 45th moved swiftly inland, overran Italian defensive positions, and took their first prisoners.

The 1st and 4th Ranger Battalions were attached to the 1st Infantry Division, while the 3rd Ranger Battalion was attached to the 3rd Infantry Division. Watching the LCIs carrying his men toward the shore at Gela, Lt. Col. William Orlando Darby, the founder and commanding officer of the Rangers, remarked, “Two of them hit the sandbar and stuck, but the center boat leaped over the bar and closed on the beach. A man aboard had been shot and fell off the bridge, hitting the telegraph key. The accidental signal sounded like ‘full speed ahead,’ and the boat got the extra surge of power needed to hurdle the sandbar.”

By late afternoon on the 10th, working methodically through town, the Rangers had subdued all resistance in Gela, even beating off an attack by Italian tanks at one point. Omar Bradley, Patton’s deputy commander, wrote that Darby had personally “commandeered a 37mm AT gun, hoisted it into the jeep, and sped back into town. With this makeshift ‘tank destroyer,’ he engaged the Italian force. Several tanks were soon knocked out and the rest fled in alarm.” For his actions, Darby was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

By the evening of D-day, Allied commanders were cautiously optimistic that the invasion had been a success. Three American, three British, and one Canadian division were ashore, and the ports at Licata and Syracuse had been captured. Now came the next phase: moving inland and securing the entire island. Controlling ports and airfields for a continued buildup of supplies and reinforcements was essential, so Montgomery was given the task of taking all airfields in Eighth Army’s sector while Patton’s army was to take the airfields at Ponte Olivo, Biscari, and Comiso.

On July 11, Patton called for elements of Matthew Ridgway’s American 82nd Airborne Division to be dropped over southeast Sicily. Colonel Gavin, commanding the 505th PIR (and augmented by a battalion from the 504th PIR) in its first-ever combat drop, ran into problems—not from the enemy, but from the U.S. Navy.

While flying over the invasion fleet on the way to their drop zones, the C-47s carrying the paratroopers were hit by antiaircraft fire from nervous gunners who thought the planes were another wave of enemy bombers (minutes before, the Navy had been hit by a 30-plane Luftwaffe raid).

As a result, 23 of the 144 C-47s were shot down, and more than 400 paratroopers became casualties (81 were killed, including the division’s assistant commander, Brig. Gen. Charles Keerans).

The chaos actually aided those paratroopers who made it safely to the ground. Although scattered over a wide area far from their objectives, the men improvised their assignments—cutting enemy communications, destroying bridges, setting up roadblocks, and conducting ambushes against German and Italian motorized columns. The result was that the enemy thought there were 10 times as many parachutists as there actually were.

Radio Rome broadcast that five or 10 American airborne divisions had landed in Sicily—60,000 to 120,000 men. The actual number was 3,405.

Also on the 11th, the Germans, disdainful of the Italians’ stomach for a fight, staged a counterattack against Terry Allen’s 1st Infantry Division at the Ponte Olivo airfield north of Gela. But no matter how many tanks and truckloads of infantry the Germans employed, they could not stop the Yanks or Brits.

In the British sector, the infantry moved swiftly toward their assigned objectives and ran into more trouble trying to corral the hordes of surrendering Italians than they did trying to fight them. Also, as the Canadians were moving to capture the airfield at Pachino, a Canadian soldier fired a shot toward an Italian gun battery north of the town. Without firing back, 38 Italians came out of their positions with their hands up.

Approaching the airfield itself, the Canadians engaged in a brief firefight with an Italian unit. After one of the Italians was killed, the rest of the unit—12 men— quickly surrendered.

On July 12, General Montgomery pulled a “power play” that rankled nearly everyone in the U.S. 45th Division and caused some serious problems between the American and British high commands. Monty had been forced to abandon his costly attempts to break through the tough German defenses on the eastern coastal highway and unilaterally decided to skirt Catania by moving inland around Mount Etna’s volcanic cone.

Highway 124, which ran northwest from Vizzini to Caltagirone and then to Enna, was in the 45th’s sector, and the division needed it to continue its push. Without waiting for approval from higher headquarters, and without informing Patton, Bradley, or Middleton, Monty decided to cut across the 45th’s front and appropriate Highway 124 for use by his Eighth Army troops.

Just after 5 pm on the 13th, with the 157th Regiment preparing to assault Vizzini, the regimental commander was more than a little surprised to find the British 51st Highland Division moving up the highway, clearly in the American sector, also on its way to attack the town. He asked for a clarification.

Alexander, Ike’s deputy, informed Patton that Highway 124, the Vizzini-Caltagirone road, now belonged to the British and was off limits to the Americans. The next day Patton gave Bradley the bad news: “We’ve received a directive from Army Group, Brad. Monty’s to get the Vizzini-Caltagirone road in his drive to flank Catania and Mount Etna by going up through Enna. This means you’ll have to sideslip to the west with your 45th Division.”

Shocked, Bradley responded, “This will raise hell with us. I had counted heavily on that road. Now, if we’ve got to shift over, it’ll slow up our entire advance. May we at least use that road to shift Middleton over to left of Terry Allen?”

Patton vetoed the request, which set Bradley’s blood to boiling. Montgomery’s move meant that the 45th would have to pull all the way back to the beaches, go around the rear of the 1st Division, and restart its advance northward. Thus was born Patton’s and Bradley’s antipathy toward Montgomery.

The Canadian division passed by the 157th on its way to Vizzini, but the fight for the town bogged down, and the Canadians asked the 157th’s commander for assistance. Ignoring the orders to let the Eighth Army stew in their own juices, the 157th came to the aid of their northern brethren, taking the high ground west of Vizzini and smashing resistance until the Canadians could enter and secure the town. After the action, the 157th climbed into trucks and was taken back to the beachhead, where they could start their advance anew.

Omar Bradley noted, “By midnight of July 16, the 45th Division had completed its roundabout move from the Vizzini road into position on Allen’s left. Middleton lost no time in getting started; he attacked at dawn the next morning. For six days and nights the 45th Division advanced across the center of the island in one of the most persistent nonstop battles of the Mediterranean war. Confined to a single northbound road, Middleton leapfrogged his regiments one through another to attack both day and night.”

July 13 saw the arrival of two additional British combat units: Lt. Col. John Durnford-Slater’s No. 3 Commandos and Lt. Col. Alistair Pearson’s 1st Parachute Battalion of Brigadier Gerald Lathbury’s 1st Parachute Brigade. The latter unit was dropped south of Catania with orders to secure the 400-foot-long Primosole Bridge over the Simeto River, while the Commandos, landing from the sea, were to seize the 750-foot-long Ponte dei Malati Bridge over the Leonardo River, five miles away. With the two bridges under British control, Montgomery would be able to quickly reach Catania from Syracuse.

As No. 3 Commando approached the coastline, the enemy opened fire, but Slater’s men managed to get ashore and take out two pillboxes on the beach. By dawn, as many as 300 Commandos were in place, guarding both ends of the bridge.

Near the Primosole Bridge, the British paras were also moving into position, but they had had a rough ride. Like the American paratroopers, Lathbury’s men had been scattered, and only about 20 percent of the brigade had been dropped in the correct location. Nevertheless, the few paras set about in the dark trying to secure their objective.

Lieutenant Colonel John Frost, who would later distinguish himself at the “bridge too far” at Arnhem, Holland, was in command of the 2nd Battalion, which counted just 50 men. As Frost was heading for the bridge, he ran into Lathbury’s group. Together, the two forces made their way to the bridge only to discover that 1st Battalion had beaten them to it.

Before dawn, additional men straggled in. Machine guns and antitank weapons that the Italians had abandoned were now in their hands. More than 200 men now faced off against Group Schmalz, which contained the 115th Panzergrenadier Regiment and the German 4th Parachute Regiment, which had been dropped near the bridge shortly before the British arrived.

During the morning, at the Malati Bridge the Commandos were coming under increasing pressure. German and Italian tanks, backed by three battalions of a panzergrenadier regiment plus Italian infantry, had arrived and were hammering the Brits. The 50th Division, which was supposed to have reinforced the Commandos, was nowhere to be seen; the division had been delayed fighting its way northward.

The paratroopers at the Primosole Bridge were also under increasingly heavy assault. The Germans mounted attack after attack against the Brits with tanks, infantry charges, mortar and artillery barrages, and even FW-190 fighter bombers.

The coastal city of Augusta, north of Syracuse, fell to the British on July 13 after heavy fighting. As the 50th Division pushed northward, it was also pushing German and Italian units in front of it—directly toward the two bridges. The fighting became desperate and was relieved only by the timely arrival of the cruiser HMS Mauritius and her six-inch guns, which, as an officer said, “made a hell of a difference.”

Although the naval shelling brought a halt to the enemy attacks, orders were given for the paratroops at Primosole Bridge to pull out. Late on the 14th, the timely arrival of the 4th Armoured Brigade and Durham Light Infantry prevented the Germans from blowing the bridge. A day later, the Durhams crossed the bridge but were sent to ground by intense enemy fire. Not long after, the British forces were withdrawn back to Syracuse. Montgomery would have to find another way to get his army north to Messina. (See WWII Quarterly, Spring 2013.)

The 45th was heading for the Biscari airfield on the 13th when two companies of Tiger tanks from the Hermann Göring Panzer Division appeared and a full-scale battle broke out. Scattered and outnumbered, the 1st Battalion of the 180th found itself in an untenable position, hammered by machine guns, tanks, mortars, and artillery, and strafed by German aircraft. The battalion commander, who had preached in training about never being captured, was taken prisoner.

On the 14th, the 45th’s 180th Infantry Regiment was maneuvering to reach the Biscari airfield when Captain Ellis Ritchie of Company E was spotted by the crew of a German Mark IV tank. Firing at him from point-blank range, the panzer crew blew a tree behind him in half. Ritchie coolly directed his men to take out the tank with rifle grenades; they did.

First Lieutenant Bill Whitman, Company B, 180th, recalled his company’s attack on the airfield: “Individual fights broke out all over the slopes leading up to the airfield, and it was all hand-to-hand in the semi-dark with the gun crews. One of my men beat a German officer to death with his helmet.”

After digging up a minefield with their bare hands, Whitman and his men finally made it to the airfield. Ordered to sweep the supposedly deserted airfield for the enemy, Lieutenant Whitman was shocked to find the place crawling with Germans. “The planes contained snipers and the buildings concealed machine guns,” he said. “Turrets on the planes swung around, opening fire with machine guns.”

The Americans blasted every position they could find. “One of my men had a scare,” said Whitman. “He pulled the door open on a plane and was confronted with a dead German in a sitting position pointing a burp gun at him. He riddled the Kraut before he found out that he was already dead. The men kidded him about it for days.”

It was shortly after the airfield was captured that the reputation of the 45th Division suffered a serious blow. On the 14th, after a fierce firefight, Captain John T. Compton’s Company C, 180th Infantry Regiment rounded up a group of 36 Italian snipers, some dressed in civilian clothing. Apparently remembering a speech Patton had given the previous month in which he had said that if the enemy fired on medics or wounded soldiers or were dressed as civilians they should be executed. Compton had the entire group of prisoners shot.

In another incident on the same day at the same airfield, Sergeant Horace West of Company A, 180th was escorting 45 Italian prisoners to the rear for interrogation when, for unknown reasons, he halted the group and shot them all with his submachine gun. Both Compton and West were court-martialed and convicted. West was reduced to private but later returned to duty. Compton was reassigned to the 45th’s 179th Regiment; he was killed in action in Italy in November 1943.

In the 3rd Infantry Division’s sector on July 13, at a town called Campobello, General Truscott moved forward to observe a firefight taking place. After the enemy resistance had ended, Truscott said, “I went over to look at the scene of action. A dozen or so Germans lay dead, a number of wounded were being cared for by American aid men, and several prisoners were being marched off. It was the first time I had seen Germans killed by infantry fire in front-line action.”

Four days later, 1st. Lt. David C. Waybur was leading a three-jeep patrol near Agrigento in search of an isolated Ranger unit. Truscott related that Waybur “was seeking a way across the Drago River, had come upon a destroyed bridge almost under the northern walls of [Agrigento]. There the patrol was attacked by four Italian tanks and most of its members wounded. Waybur, although himself wounded, stood with his tommy gun on the road immediately in front of the leading tank and killed two of its crew by firing through the ports, whereupon the driverless tank plunged into the chasm beneath the destroyed bridge.

“There, Waybur and his gallant patrol held off the remaining tanks until elements of the 3rd Reconnaissance Troop arrived some hours later. For this heroic action, Waybur received the Medal of Honor. Besides heavy casualties, inflicted upon the enemy in killed and wounded and in destroyed vehicles and equipment, the reconnaissance in force yielded more than 6,000 prisoners, more than a hundred vehicles and tanks, and more than 50 pieces of artillery….”

The distance between the Allies’ landing beaches and Messina, in the northeast corner of the triangle-shaped island, is not great, but most of Sicily’s terrain is extremely rough and mountainous with few good roads. Additionally, the operation was taking place in the middle of summer, and Sicily’s summers are scorching hot; soldiers trying to scale the rocky crags began suffering from heat exhaustion at an alarming rate.

On July 18, Middleton’s 45th Division wearily trudged into Caltanissetta, a railroad junction city of 60,000 people and a former hotbed of Fascism. On the outskirts, Brig. Gen. Raymond McLain, the division’s artillery commander, saw an old man “carrying the mangled form of a boy about ten. The boy was still conscious…. A doctor came by and I sent him to do what he could, but the boy was dying then. Later I learned the child had picked up a German grenade left alongside the road and it had exploded. They left many little red grenades along the road. The Division chaplain said he had found two corpses with these grenades, with the pin pulled, pushed in the dead man’s pocket so that, when removed, they exploded.”

The next day, July 19, Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division and Hugh Gaffey’s 2nd Armored Division, nicknamed “Hell on Wheels,” began their drive toward Palermo in the northwest part of the island. The 3rd Division commander recalled standing by the side of the dusty road as his soldiers went marching and driving by: “In blistering heat and stifling dust, these soldiers plowed their way forward like waves beating on an ocean beach and at a rate which Roman legions never excelled.” As each battalion went by, Truscott asked how many men had fallen out. The answer was none.

But the 3rd Infantry-2nd Armor column was held back from entering Palermo until Seventh Army gave permission. Troops on the surrounding hills could see explosions coming from the city, a sign that the Germans, like angry tenants on the eve of eviction, were doing their best to wreck the place before they moved out.

Finally, after hitting the city with aerial bombardment and an artillery barrage, the Americans entered Palermo on July 22 with surprisingly little resistance. Italian soldiers were giving up en masse and at a rate that Truscott thought was “embarrassing.” The Palermitans rushed into the streets at the first sign of the dust-covered Yanks, showering them with flowers and kisses and glasses of vino. Also aiding in the capture of the city was Maj. Gen. Manton Eddy’s U.S. 9th Infantry Division, brought in by sea.

Patton was immensely pleased with his army’s performance. After he drove past a column of 2nd Armored Division tanks and vehicles on the road into Palermo, he wrote, “I received a very warm reception from the 2nd Armored, all of whom seemed to know me [he had commanded the division for a year in 1941-1942] and all of whom first saluted and then waved.” As he approached the city he noted, “The street was full of people shouting, ‘Down with Mussolini!’ and ‘Long live America!’”

Patton also said, “I believe that this operation will go down in history…. I also believe that historical research will reveal that General Keyes’s II Corps moved faster against heavier resistance and over worse roads than did the Germans during their famous Blitz.”

In a letter to his wife shortly after the keys of the city were turned over to the Americans, Truscott wrote about his impressions of Sicily: “This is a most interesting island…. I have never seen so much poverty and filth.” He also noted, “The censor will permit me to say that I am now in Sicily, and you will guess that the division has been in the forefront. It has done well. I do not believe that the equal of these men has ever existed in our Army—though I will admit that I may be somewhat prejudiced!”

On July 23, before he had time to savor the capture of Palermo, Patton was ordered by Alexander to proceed eastward to Messina. Hearing that both Alexander and Montgomery—still under the impression after the Kasserine Pass debacle in Tunisia that the Americans were inferior soldiers—had maligned his Seventh Army, he decided to beat Monty to Messina as a way of proving the superiority of American troops.

Having reached the northern coast of the island, the 45th Division was given its marching orders: head to Messina with all possible speed. It was an order easier given than obeyed. The coast was incredibly mountainous with but a single highway permitting movement. The Germans could slow or even stop the Thunderbirds’ progress by blowing a bridge or setting ambushes anywhere along the 100-mile route.

With most of Guzzoni’s troops having been captured or deserted, the Italian contribution to the defense had melted away, so German General Hans Valentin Hube became the de facto officer in charge. The Germans had established an “Etna Line” beginning from an area north of Catania, encircling Mount Etna, and then extending northward across the Nebrodi Mountains to the sea. It was through this line that both the Seventh and Eighth Armies were trying to penetrate on their way to Messina.

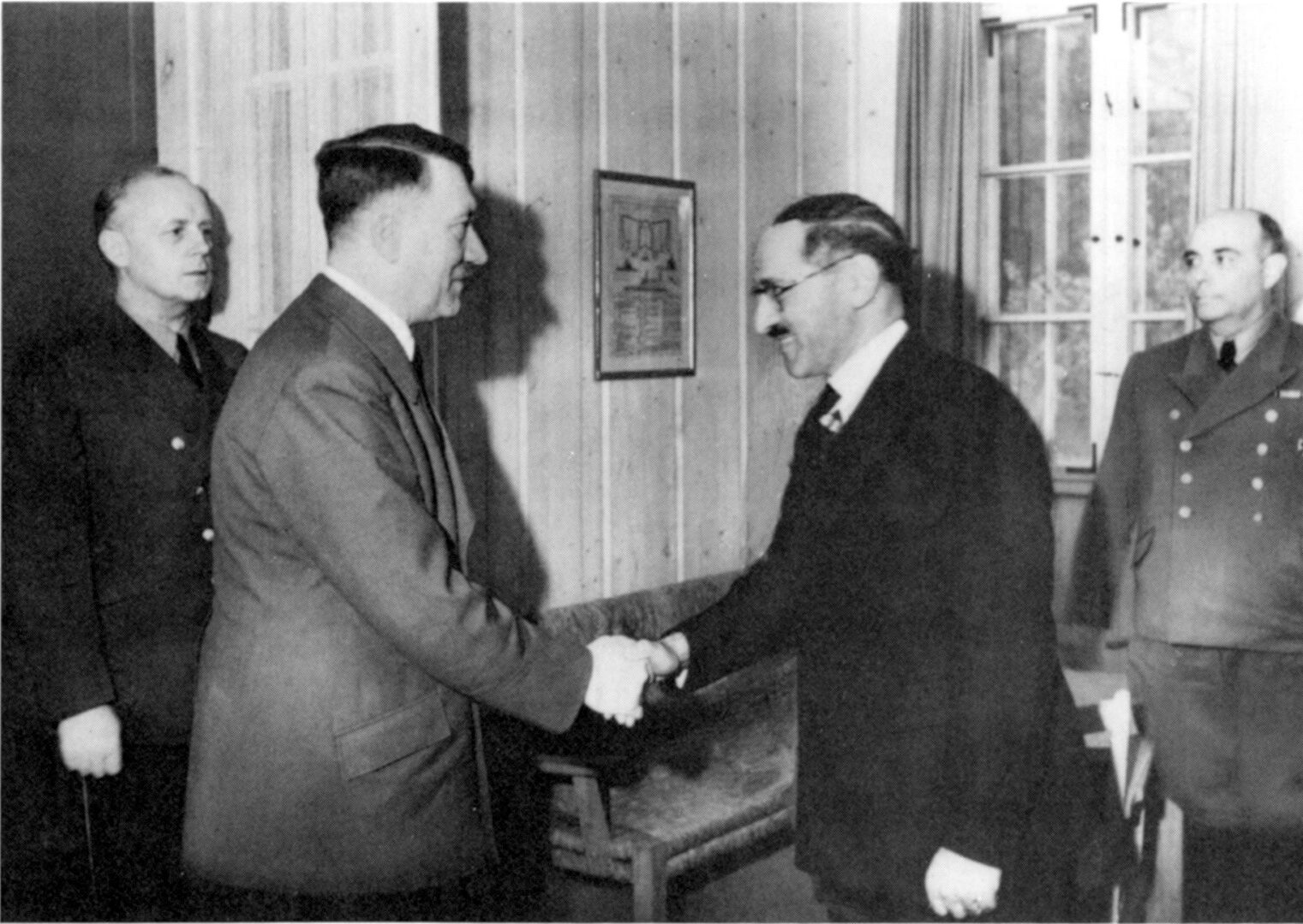

As the Allies were clawing and scratching their way across Sicily, important developments were taking place in Rome. After American bombs fell on two railroad marshaling yards and an airbase in the Eternal City and Palermo fell to American troops, a political crisis boiled up and an anti-Mussolini backlash erupted.

On July 25, a vote of no confidence by the Fascist state’s Grand Council shocked the dictator, and he appealed to King Victor Emmanuel III for support. The king expressed his displeasure with Benito Mussolini’s conduct of the war and the affairs of state. Stunned and humiliated, Mussolini had no choice but to resign—and was promptly arrested.

In his place, a caretaker government under the aging, anti-Fascist Field Marshal Pietro Bodoglio was installed and immediately proclaimed that the war, and Italy’s role in it, would continue—while simultaneously holding secret talks with the Allies that would lead to Italy’s capitulation.

The Romans, who once lustily cheered Mussolini, marked the fall of the Fascist government with wild revelry. In Sicily, more than 120,000 Italian troops celebrated the news by deserting or surrendering, although some continued to fight alongside German units.

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commander in chief of German troops in southern Italy, told Hitler on July 29 that he was making plans to evacuate the bulk of his troops from Messina to Reggio di Calabria on the Italian mainland; Hitler, who hated giving up any territory without a fight and feeling he had been stabbed in the back by the Italians, reluctantly approved the evacuation from Sicily of as many German units as possible.

The steady withdrawal of German troops across Sicily toward the city of Messina—only a mile from the Italian mainland—turned into a raging river of gray-uniformed humanity.

At the hilltop town of Troina, the 1st Division faced its toughest challenge to date. The town was built atop a ridge that dominated Highway 120 and the surrounding barren countryside. Considered a natural strongpoint, Troina and its environs are extremely steep with little room for an attacking force to maneuver.

Troina had seen plenty of warfare over the eons; in the 11th century, the last battles between the Normans and Saracens were fought there. The modern battle, which began on July 31, did not go well from the start. For openers, both II Corps and Division Intelligence had failed to detect the presence of four enemy divisions—all of them seasoned fighters—firmly entrenched inside the town’s stone buildings and surrounding mountain and determined to keep open the German escape route to Messina.

Terry Allen’s Big Red One was worn out from three weeks of nearly continuous, uphill fighting in stifling heat. The division was below strength, too, due to malaria and the heavy casualties suffered since the landings.

The unsuspecting Americans, advancing from Cerami, were a mile west of Troina when the Germans unleashed a storm of artillery shells that brought the advance to a halt. Three days later, the 1st had advanced only a few hundred yards, all the while taking a severe pounding from the German guns that not even aircraft could knock out.

On August 3, Allen’s men launched a night attack by the entire division that very nearly succeeded. The Germans struck back with a fierce counterattack, however, and there the matter stalemated. The fifth day of the battle, August 4, began with an air and artillery bombardment of German positions, but still the enemy refused to be dislodged.

So furious was the fighting that Private James M. Reese of the 1st Division’s 26th Infantry Regiment was awarded the Medal of Honor, posthumously, for breaking up a German counterattack with his mortar.

The German defenders had done their job well, delaying the Americans for nearly a week to allow their comrades to escape across the Strait of Messina—units that would live to fight another day on the mainland. Under the cover of darkness on August 5/6, the enemy began slipping quietly out of Troina and the neighboring mountains. On the morning of August 6, Allen’s men entered the shattered town to find the enemy gone.

The 1st Division had taken heavy casualties, but none was greater than the loss of its beloved commander, Terry Allen, and his assistant, Teddy Roosevelt, Jr.—son of the famed Rough Rider and U.S. president—who were both relieved of command. There is still some question as to who actually ordered the firings. Some say it was Patton, while others blamed Walter Bedell Smith, Patton’s chief of staff. In his autobiography, Bradley took responsibility.

The reasons are equally hazy; some thought it was because the division had taken an inordinate amount of time to subdue Troina. But, according to Bradley, it was something deeper: “Under Allen, the 1st Division had become increasingly temperamental, disdainful of both regulations and senior commands. It thought itself exempted from the need for discipline by virtue of its months on the line. And it believed itself to be the only division carrying its fair share of the war.”

Another source quipped, “The trouble with the Big Red One is that it thinks the U.S. Army consists of the 1st Infantry Division and 10 million replacements.”

The division’s simmering anger at the firing of Allen and Roosevelt, however, was directed at Patton, whom they thought was behind the move. These feelings became more intense after it was discovered that “Old Blood and Guts” had slapped two enlisted men (one of whom was a 1st Division soldier) who had been admitted to field hospitals on Sicily for “battle fatigue,” but which Patton thought was malingering and cowardice. Once the story broke in the American press, Eisenhower ordered Patton to personally apologize the all of the units of Seventh Army. He would relieve Patton of command of Seventh Army after the Sicily campaign was over.

Much to the anger and dismay of the 1st Division soldiers, most of whom truly loved Allen and Roosevelt, their two popular commanders were given the boot and a new boss, a strict disciplinarian named Clarence Huebner—who had served with the division as a private in the previous world war—was brought in.

At first the men loathed Huebner, who would later command them at Omaha Beach during the Normandy invasion, but in time he would earn their grudging respect and even affection. As one old soldier later said, “He was the greatest soldier there ever was. He was a wonderful division commander.”

But that was in the future. The Sicily campaign was not yet over. The Germans thought they still might be able to stop the Allies—or at least inflict such heavy casualties that the British and American publics would demand that their leaders consider a negotiated peace. Therefore, considerable Axis reinforcements had poured back into Sicily. These were elements of the 1st Parachute Division, 29th Panzergrenadier Division, and the headquarters of the XIV Panzer Corps—a total of about 70,000 men.

The fighting, which had been difficult, now became intense. While the British were battling for their lives at every little village and trying to maneuver around the heavily fortified slopes of Mount Etna, the 45th Division was on Highway 113 and battling its way across the northern coast of the island.

As with the rest of Sicily that had already been conquered, it seemed that a raging battle had to be fought at every hamlet, every bridge, every intersection. On the night of July 26/27, the 157th Regiment passed through the 180th at Castel di Tusa and headed for the village of Motta D’Afformo where, at a high, rocky ridge west of San Stefano, the Thunderbirds met their greatest challenge on Sicily.

Called “Bloody Ridge” by the Yanks, the rocky, cactus-covered area, also known on military maps as “Hill 335,” bristled with strong fortifications, pillboxes, minefields, and other defensive works. The jagged coastline, intercut with deep gorges and dry streambeds, offered little room for maneuver. It was here that the Germans were determined to stop the American drive long enough for the rest of the defenders to escape across the Strait of Messina.

As the 157th Regiment tried scrambling up the steep slopes, the Germans unleashed torrents of mortar, artillery, and machine-gun fire down upon them. Sergeant Henry Havlat, Company B, 157th recalled, “We had tough going on Bloody Ridge. One of my men, about 10 feet from me, hit a trip wire. The last word he said was my name. Then a mine blew up and his head came off. That’s when the artillery came in. The first shell got me. I got hit in the right lung, and got half my right shoe shot off, and another chunk got me in the back.”

The battle for Bloody Ridge lasted all of July 28, with untold stories of heroism written in blood for every yard taken. As the sun went down, grenades flew back and forth and the artillery continued to pump out shell after shell; the German barrage never slackened. “The next day,” recalled Sergeant Vere Williams, 157th, “the Navy came into the bay and a few salvos made the Germans move on.”

On July 31, the exhausted 45th Division was relieved at Cefalu by the 3rd Division, which continued battling toward Messina. From August 1-10, the Germans performed their own Sicilian version of the “Miracle of Dunkirk.” During that period, General Hube managed to evacuate his XIV Panzer Corps to the Italian mainland—more than 12,000 men, 4,500 vehicles, and 5,000 tons of equipment. Allied efforts to interdict the evacuation by aerial bombing were, at best, ineffective.

By August 18, the numbers would grow to 60,000 German soldiers, plus 14,000 vehicles, 47 tanks, 92 guns, and more than 21,000 tons of ammunition and other supplies. The Italians, too, removed anywhere from 62,00 to 75,000 men. The Allies would see them again in September, when the Americans and British invaded southern Italy.

While Patton was trying to make a point by beating Montgomery to Messina, Monty would not make a race of it. He wanted only to keep the Germans from escaping and realized Patton was in the best position to accomplish that. In fact, he urged Patton to use roads assigned to the Eighth Army.

At 4:30 am on August 17, once the 45th had caught its breath, a patrol from Company B, 1st Battalion, 157th became the first Allied unit to enter the city. The enemy had fled. The streets were quiet. The Thunderbirds were followed by British Commandos and Truscott’s 3rd Division. The citizens were grateful that at last the war had ended in Sicily.

The Allies had suffered heavy casualties during the month-long battle for the island. Patton’s Seventh Army lost almost 9,000 men (including more than 2,200 killed), while Monty’s Eighth Army lost nearly 12,000 (including just over 2,000 killed). Combined losses for the British and American air forces and navies came to 886.

The Germans and Italians came out worse. While figures are imprecise, it is estimated that the Germans lost in killed, wounded, captured, or missing, from 20,000 to 28,000 men, while the Italian numbers have been estimated at between 147,000 and 190,000—most of whom were happily in prison camps.

The question has often been asked: How did the Allies allow so many enemy troops to escape to continue the fight on the Italian mainland, given the superiority of the Allies’ ground troops, naval, and aerial assets? Several answers have been offered. First, the Strait of Messina was protected by more than 230 antiaircraft guns. The Allied fleet was kept at bay by strong coastal defenses and a swift current, and intelligence had learned that the Italian Navy might attack any Allied ships in the Strait with suicide runs. The answers seem unsatisfactory.

Some historians have written that the decision to invade Sicily in the first place was a huge mistake, that the resources employed to conquer the island could have been better used to invade France in 1943 instead of 1944. It is an argument that will never rest. But, if nothing else, the seizure of the strategic island opened the sea lanes in the Mediterranean to Allied shipping, especially the shipments of Middle East oil that Britain relied upon—sea lanes that had been closed since 1941.

Just as important, the “lessons learned” at Sicily, especially how to conduct a combined air and sea invasion of a hostile shore, were used by Eisenhower and his staff as they prepared to mount the biggest air and sea invasion in history at Normandy.

Despite the criticism, a victory is a victory, even if the enemy has been allowed to slip away to fight another day. Mussolini was finished, and Italy was out of the war as an Axis partner; Hitler was forced to expend scarce resources in a theater he could no longer win, and certainly that contributed to the Allied cause and ultimate victory.

In a message to his Seventh Army troops on August 22, Patton wrote: “Born at sea, baptized in blood, and crowned with victory, in the course of 38 days of incessant battle and unceasing labor you have added a glorious chapter to the history of war.

“Pitted against the best the Germans and Italians could offer, you have been unfailingly successful. The rapidity of your dash, which culminated in the capture of Palermo, was equaled by the dogged tenacity with which you stormed Troina and captured Messina. Every man in the army deserves equal credit….

“But your victory has a significance above and beyond its physical aspect—you have destroyed the prestige of the enemy…. Your fame shall never die.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments