By William F. Floyd Jr.

With weapons at the ready, the American squad advanced cautiously on both sides of the tree-lined boulevard toward the German strongpoint in Aachen. Buildings pummeled by Allied shells had toppled to the ground, sending concrete and bricks spilling into the street. Hardly a structure remained intact as a result of the protracted fighting.

As the squad moved toward an intersection, it directed its fire on the corners of the block of apartment houses that lay ahead. Soldiers darted hurriedly across the street as they moved from building to building. While trying to knock out the strongpoint, they began taking fire from another German-held apartment building down the street. The American platoon leader, who was watching the action from a corner room window, called for assistance on his field telephone.

Soon a large vehicle arrived. American mortar teams on rooftops kept a steady fire on the enemy as the M12 moved into position. An M12 was a self-propelled gun that consisted of a French World War I-era 155mm field gun mounted atop an M4 tank chassis. It was tailor made for such situations.

The driver of the tracked vehicle steered it into a concealed position behind a pile of rubble. The crew sighted the barrel toward the building where the enemy fire had originated. The gun roared, sending a large shell into the upper half of the building. It blew a gaping hole in the side of the building and sent debris raining down into the street below. A second round caused the top three floors of the six-floor building to collapse. The American squad waited for a few minutes, and then it cautiously entered the remains of the building to clear it of any surviving German troops. Afterward, engineers set up booby traps in some of the rooms to discourage other Germans from reoccupying the buildings.

The vignette describes the tedious tactical fighting that characterized the Battle of Aachen fought from October 2 to October 19 just inside the German border in North Rhineland-Westphalia. The Germans intended to fight to the death for the Fatherland in response to the exhortations of German leader Adolf Hitler and his staff.

After nearly two months bottled up in Normandy, the Allies broke out from the bocage country in late July 1944. The German forces, forced to fight in open terrain against a foe with superior numbers of men and equipment, were encircled in costly battles, such as the Falaise Pocket in August that cost them 60,000 men and 500 tanks and assault guns. In the three months following D-Day, the Germans lost upward of 300,000 men on the Western Front.

The race across France toward the German frontier ground to a halt in early September. As the Allies approached the German frontier, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group held the extreme left flank of the Allied line and General Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group was positioned on its right.

Eisenhower approved Monty’s elaborate plan for Operation Market Garden in which Allied forces would leapfrog over the rivers of Holland through a combination of river assaults and air drops. The operation, which began on September 17, involved British, American, and Polish forces. To the end of his life, Eisenhower believed that Market Garden was a risk that the Allies had to take even though it was a disastrous failure. The Allied defeat was the result of a number of factors, including supply limitations, bad luck, and unrealistic tactical objectives. Unfortunately for the Allies, Montgomery and Eisenhower resumed their previous acrimonious relationship, with each blaming the other for the failure of Market Garden. Afterward, the race to Berlin became a slog to get through the Siegfried Line that guarded Germany’s western border.

German forces in the West braced to defend their homeland against the fast-moving Allied forces that were as much as eight months ahead of their timetable for the liberation of Germany. The Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force hoped to seize the Ruhr, which was the industrial heartland of Germany, to stifle any further war production.

Bradley assigned Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ First Army to break the German front near Aachen. First Army comprised 40 infantry and airborne divisions and 15 armored divisions. In the center of First Army was the VII Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, known as “Lightning Joe” to his troops. Collins did not want to get bogged down in house-to-house fighting in Aachen, so he decided to surround the city in the hope that the Germans might decide to pull out. However, such an approach failed to take into consideration German leader Adolf Hitler’s fortress mentality and his obsession with not giving up a town as historically significant as Aachen. “The Führer wanted to defend Aachen to the last stone,” Field Marshall Hermann Göring said after the war. “He wanted to use it as an example for every other German city, and defend it, if necessary until it was leveled to the ground.”

The Germans considered Aachen to be hallowed ground. It was the presumed birthplace, as well as the coronation site, of Frankish King Charlemagne, who became the first Holy Roman Emperor. For 600 years afterward it was the seat of power for Imperial Germany, and the majority of the emperors were crowned in its stately cathedral. The old Imperial city held great psychological value for the Germans and particularly for Hitler, who regarded it as the founding city of Germany’s First Reich.

Hitler instructed that the city was to be held at all costs. He ordered the staff of the Oberkommando des Heeres (Supreme High Command of the German Army) to ensure that it did not fall to the Allies. “Every bunker, every dugout, every town, every village must become a fortress against which the enemy will beat his head in vain or in which the German garrison goes under in hand-to-hand combat,” wrote General Alfred Jodl, chief of the German Operations Staff, in a September 16 order.

Aachen was situated in a saucer-shaped depression 45 miles west of the Rhine River. The city was surrounded on all four sides by hills and ridges that rise between 300 and 500 feet above the city. At the outset of the war, Aachen had a population of 165,000, but Hitler had ordered the city evacuated and only 20,000 remained.

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, commander of Oberbefehlshaber West (German Army Command in the West), on paper had 48 infantry divisions and 15 panzer and panzergrenadier divisions, but all of the divisions were below strength. The Allies also had a decisive advantage in equipment and matériel. They outnumbered the Germans in artillery pieces nearly 3 to 1, and had a staggering 20 to 1 advantage in tanks. While the Allies had more than 13,000 military aircraft, Luftflotte Kommando West had just 573 aircraft.

Fortunately for the retreating Germans, the terrain in western Germany on the west side of the Rhine favored the defenders. It consisted of urban industrial areas and rivers and woods that would be obstacles to the advancing Allied forces.

The defense of Aachen fell to General Friedrich-August Schack’s LXXXI Corps. The corps was part of General Erich Brandenberger’s 7th Army of Field Marshal Walter Model’s Army Group B. Schack was replaced in late September by General Friedrich Kochling.

Schack had four infantry divisions—two regular divisions and two Volksgrenadier divisions—to defend Aachen. The infantry was supported by General Gerhard Graf von Schwerin’s 116th Panzer Division. The regular infantry divisions were Colonel Gerhard Engel’s 12th Infantry Division and Generalleutnant Siegfried Macholz’s 49th Infantry Division. The Volksgrenadier divisions were Generalleutnant Wolfgang Lange’s 183rd Volksgrenadier Division and Colonel Gerhard Wilck’s 246th Volksgrenadier Division. The effective strength of the four divisions was 18,000 men. They had a total of 140 105mm guns, 84 150mm guns, and 15 heavy guns.

Some of the divisions arrived while the fighting raged and were fed directly into the battle. Engel’s 12th Infantry Division, which had been reconstituted in the late summer in East Prussia after service on the Eastern Front, arrived at the front in buses and trucks on September 16. Lange’s Volksgrenadiers, who had been stationed in Bohemia, arrived on September 22.

Schwerin’s division had 1,600 men, three PzKpfw IV tanks, two Panther tanks, and two StuG III assault guns. To round out his depleted ranks, he was given two fortress battalions and some Waffen SS and Luftwaffe troops.

When Schwerin, who was entrusted with overseeing the defense of the city, arrived on September 12 he found that antiaircraft crews, police, municipal bureaucrats, and Nazi Party officials all had fled toward Cologne. Schwerin, who was a highly decorated Prussian aristocrat, countermanded Hitler’s order for the evacuation of all civilians. He made every effort to restore order as quickly as possible. He sent troops to secure the city with orders to shoot looters. He also urged the remaining citizens to return to the relative safety of their homes.

“I have stopped the absurd evacuation of this town; therefore, I am responsible for the fate of its inhabitants and I ask you, in the case of an occupation of your troops, to take of the unfortunate population in a humane way,” Schwerin wrote in a letter to be given to the American commander upon the capture of the city. His letter fell into the hands of the Nazis, and he was tried for cowardice by the People’s Court. In a rare decision, Hitler only issued a reprimand. Nevertheless, Schwerin was relieved of command of the city. His superiors transferred command of the beleaguered city to Wilck.

The Germans had begun construction on the Siegfried Line in 1938. Aachen was sandwiched between two bands of pillboxes. The Scharnhorst Line was situated west of the city, and the stronger Schill Line was located east of the city. Each contained pillboxes, bunkers, minefields, and antitank obstacles and ditches. The tank obstacles included rows of concrete pyramids known as Dragon’s Teeth. The fortifications were set up with interlocking fields of fire intended to enable the defenders to annihilate attacking formations.

Spearheading the VII Corps advance was Maj. Gen. Clarence Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division. Huebner’s veteran division comprised the 16th, 18th, and 26th Infantry Regiments. It was supported by Maj. Gen. Maurice Rose’s 3rd Armored Division. The Big Red One, as the 1st Infantry Division was known, advanced toward Aachen on a 35-mile front.

The division began fighting its way into the Scharnhorst Line on September 12. The fighting that occurred from September 12 to September 29 is known as the First Battle of Aachen. The tempo of the fighting was fast and fierce, and the Germans began picking off the 3rd Armored Division’s tanks with their deadly 88mm guns. The VII Corps tank force dwindled from 300 Shermans to just 70 in a short time. Despite the heavy losses, VII Corps punched a 12-mile hole in the Scharnhorst Line.

The VII Corps armored attack occurred directly south of Aachen in an area known as the Stolberg Corridor. The corridor was a six-mile-wide passage of relatively open terrain between Aachen and the Hürtgen Forest. Collins intended to fight his way through the corridor to the Roer River. As soon as they became aware of Collins’ intentions, the Germans massed infantry and armor to halt the thrust.

The fact that American forces intended to attack the Stolberg corridor rather than move directly on Aachen was welcome news to the Germans. They shifted panzer units and issued orders for artillery units to recalibrate their guns.

Two armored combat commands of the 3rd Armored Division advanced shoulder to shoulder into the corridor. Brig. Gen. Doyle Hickey’s Combat Command A advanced on the left with its left flank on the outskirts of Aachen, while Brig. Gen. Truman Boudinot’s Combat Command B advanced on the right with its right flank resting on the Hürtgen Forest. Opposing them were the 9th and 116th Panzer Divisions. When Engel’s full-strength 12th Infantry Division arrived at the front on September 16, the Germans were able to shore up their defenses. Although Engel’s regiments were fed into the battle piecemeal, their presence enabled the Germans to launch repeated counterattacks that kept the Americans off balance and slowed their advance. By late September VII Corps’ armored thrust had lost its momentum. The Germans had paid a heavy price in casualties, though, as Engel lost half of his 3,800 riflemen.

By the end of September, Collins’ VII Corps had fought through both the Siegfried Line’s German fortifications without capturing Aachen or advancing toward the Rhine; at that point, he conferred with Hodges and they came up with a fresh approach. The influx of German forces into Aachen made it necessary to conquer the city. The Battle of Aachen would turn into a major battle, one of the largest urban battles fought by U.S. forces during the war, which was an event the Allies had hoped to avoid.

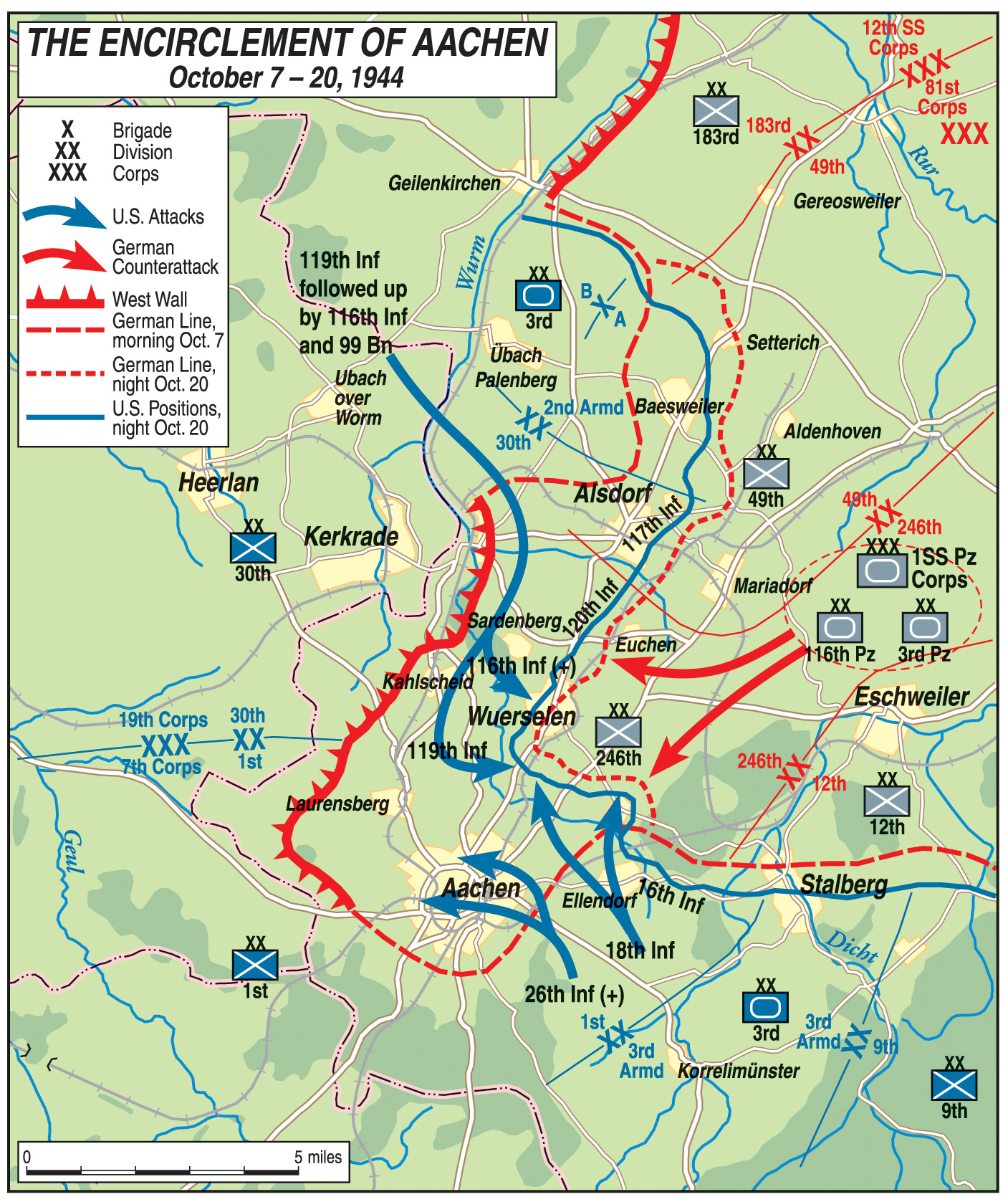

Collins’ armored thrust south of Aachen ran out of steam on September 29. A new offensive was scheduled for October 1. Under the revised plan, Maj. Gen. Charles Corlett’s XIX Corps would push south to link up with Collins’ VII Corps. The XIX Corps forces would consist of Maj. Gen. Leland Hobbs’ 30th Infantry Division, which would be supported by Maj. Gen. Ernest Harmon’s 2nd Armored Division. Meanwhile, Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division of the VII Corps would strike north, clearing Aachen and linking up with the XIX Corps.

Corlett advanced along a route eight miles north of Aachen to get into position for the fresh offensive. The XIX Corps would have to ford the Wurm River, and preparations were made for duckboard footbridges and wooden and metal culverts, respectively, to get the infantry and armor across the river.

For six days, Corlett’s heavy guns shelled the approximately 45 pillboxes in front of the 30th Infantry Division before beginning the ground attack. The artillery bombardment stripped away camouflage from pillboxes, demolished barbed wire obstacles, and touched off mines. But it took few German lives as they had good cover.

The ground assault scheduled to begin October 1 was postponed until the following day because of heavy rains that precluded air support. As was often the case with major operations on the Western Front in World War II, the initial high-altitude bombing by medium bombers of the Ninth Air Force was largely ineffective. Because of this, Corlett’s artillery units quickly went through most of their shells trying to soften up the enemy positions before a large-scale infantry assault. After its artillery barrage, Corlett’s XIX Corps was down to just 2,000 rounds. This meant that the gunners would often have to wait to receive scheduled resupplies of ammunition, which were established by First Army headquarters.

On October 2, the first day of the attack, mortar crews from the 30th Infantry Division targeted enemy pillboxes in preparation for an infantry advance. The fighting from October 7 to October 21 is known as the Second Battle of Aachen. The mortar crews lobbed more than 18,000 shells from 372 tubes. The GIs advanced against the pillboxes using satchel charges, flame throwers, pole charges, and bazookas in an attempt to neutralize the fortifications. To its credit, the 30th Infantry Division knocked out 50 pillboxes on the first day. It took an average of 30 minutes to capture a pillbox. The Germans fought tenaciously. In one firefight, the Americans suffered 87 casualties in an hour. A German counterattack the first night was a complete failure.

In spite of CCB of the 2nd Armored Division entering the battle in support of the infantry on October 3, the American forces were stopped after several German counterattacks. As the fighting on October 3 came to an end, the crossing of the Wurm River and the creation of a bridgehead had cost the 30th Infantry Division 300 dead and wounded. On October 4, the Allied advance slowed with the Americans having lost approximately 1,800 men over the past three days. The next day the 119th Infantry captured Merkstein-Herbach.

On Hobbs’ right flank, the 119th Infantry could advance no farther than a railroad embankment because the Germans had presighted their guns to cover all crossings of the railroad tracks. On his left flank, though, the 117th Infantry had made substantial progress working its way through the first line of pillboxes.

The Americans developed an effective coordinated technique for clearing pillboxes. First long-range artillery would pound the pillbox. When the big guns stopped firing, machine-gun and bazooka teams would keep the soldiers inside occupied while flamethrower teams and sappers with pole charges would attack the embrasures and doors. If necessary, M12s and Sherman tanks would fire on the bunkers.

On October 6, the Germans launched a counterattack against the 117th in Ubach, but the Americans repulsed the attack. The 119th faced tough going trying to eliminate pillboxes near the medieval Rimburg Castle. At that point, the 30th Division had penetrated five miles into the Siegfried Line along a six-mile front. On October 7, the spearhead of XIX Corps turned south to outflank Aachen.

“We have a hole in this thing big enough to drive two divisions through,” said Hobbs, adding, “This line is cracked wide open.” He believed his division’s work was done, but he could not have been more wrong. German reinforcements from Holland and as far away as Alsace had arrived. They went into action and successfully halted XIX Corps’ advance three miles short of Aachen. The process of tightening the noose around Aachen would require renewed help from the 1st Division to the south, which had succeeded in establishing a semicircular 12-mile-long front that curled around the south of the city.

The 18th Infantry launched an attack on October 8 northeast of Aachen aimed at eliminating defiant German troops in other pillboxes. The following day two American infantry companies slipped past enemy pickets without having to fire a shot and climbed the Ravelsberg, an enemy stronghold on the high ground south of Wurselen. The Americans usually gave the Germans in the pillboxes a chance to surrender, and the following morning eight pillboxes gave up.

Huebner delivered an ultimatum on October 10 to the German garrison of Aachen. He threatened to level the city if they did not surrender. Wilck declined the offer. He had about 5,000 troops to defend the rubble-strewn city. In addition to his Volksgrenadiers, he had approximately 200 grenadiers from the 1st Panzer Battalion of the 1st SS Panzer Division under the command of Hauptsturmfuhrer (Captain) Herbert Rink. Realizing the city was in danger of falling to the Allies, Rundstedt had directed the crack troops to move into the city as soon as possible.

The destruction of Aachen began in earnest on October 11. Approximately 300 Allied planes dropped 62 tons of bombs on areas marked as targets with red smoke. Over the course of the next two days, the Allies dropped another 5,000 artillery rounds and an additional 100 tons of bombs on the city.

Eisenhower constantly urged his commanders to stay on the attack at Aachen so that the Germans did not have a chance to regroup. He wanted them to maintain a constant and steady attack to wear down German resources. He knew that the Allies’ superior resources would enable them to win the war sooner rather than later. His critics accused him of adopting a sterile, costly strategy. Eisenhower made no excuses. He believed that in the long run his strategy would save thousands of Allied lives.

“People of the strength and war-like tendencies of the Germans do not give in,” he told a critic. “They must be beaten to the ground.” The fighting that resulted was some of the least glamorous and toughest of the war. There was not a whole lot of manuever and strategy involved.

The Germans counterattacked in force against the 30th Infantry Division on October 12. The attack was disrupted by artillery fire and well-placed antitank defenses. American artillery pummeled the 12th Infantry Division, firing as many as 5,000 rounds. As the bombardment continued, Lt. Col. John T. Corley’s 3rd Battalion, 26th Infantry began to clear the factories between Aachen and the city of Haaren. They completed the task by nightfall. As the fighting continued, two German infantry regiments attempted to take Crucifix Hill from the 1st Infantry Division. In a brutal firefight, the Germans temporarily occupied the hill, but they were mauled in an American counterattack at the cost of two regiments.

On the morning of October 13, Corley’s tough battalion began to push northwest toward Observatory Hill while Lt. Col. Derrill M. Daniel’s 2nd Battalion began a painstaking movement through the center of the city. Daniel’s men had to find their way through a maze of rubble and damaged buildings while keeping in contact with Corley in the hills to the north. Daniel had about 2,000 yards of attack frontage, no small amount in view of the density of the buildings. Out of necessity, the battalion’s movements would be slow and deliberate.

Daniel developed assault tactics on the spot for his battalion. To compensate for the shortage of men in his battalion, he buttressed his rifle companies with heavy firepower designed to knock out German strongpoints in order to preserve his infantry as much as possible. Daniel’s mantra regarding the city’s buildings was “knock ‘em all down.”

He established task forces consisting of a rifle company backed by either three M4 Sherman tanks or three M10 tank destroyers and including two 57mm antitank guns, two bazooka teams, two heavy machine-gun teams, and a flamethrower.

The infantry advanced along the sides of the street using smoke grenades to screen their movements from the enemy and the doorways of buildings for temporary cover. Meanwhile, the tanks and destroyers advanced directly up the street, firing into the buildings to soften up enemy positions and prepare them for a rifle squad assault. The intention was to drive the Germans into the cellars, which the rifle squads could attack with grenades. If the enemy holding a particular position proved especially tenacious, the Americans used satchel charges and flamethrowers to kill them.

The Germans in Aachen picked two or three houses in a block that offered a good field of fire. The only way to root them out was to encircle them with small units of riflemen. A major problem for the advancing Americans in these situations were snipers firing from rooftops or upper stories of buildings and the danger of mortar fire.

The Germans placed their mortars on the top floors of buildings and fire from the windows. Neither the soldier firing the mortar nor the mortar itself could be seen because they were beneath the windowsill. The Germans were not overly concerned with firing at targets they could see; instead, they lobbed shells onto main streets they knew the Americans would use.

American engineers used dynamite to blow holes through the walls or ceilings in buildings and houses in a method known as “mouseholing.” This enabled them to bypass stairwells that were likely to be defended by the Germans. This also could also be done with beehive rounds fired from a 155mm howitzer that would knock holes through several buildings at once. The shells tore clean holes through multiple walls, thus allowing the infantrymen to advance from one building to another without being exposed machine-gun and rifle fire. When the Germans converted large buildings into strongpoints, as they did with the State Theater in Aachen, the Americans used several M12s to flatten the building from a distance of 300 yards.

The American units were using every available tool to force the Germans to surrender or retreat. Three captured streetcars were each loaded with a thousand pounds of captured enemy munitions, with a delayed fuse, and rolled down the street into no-man’s land. The explosions did little damage but seemed to be a morale booster for the Americans as appreciative cheers rose from their lines. As the fighting continued on October 14, the flamethrower again showed its value when it was used to clear a three-story air raid shelter of 75 soldiers. For those holding out in bunkers, engineers from the 1st Division discovered that wedging mattresses into firing ports would raise the explosive pressure inside, causing fractures in the concrete. An order went out to gather every mattress from each occupied German village. As the Americans crept through Aachen at a slow, steady pace of 50 feet per hour, they continued shooting and dynamiting every possible hiding place.

Beginning on October 13, the 30th Infantry Division and the 2nd Armored Division continued their drive to get behind Aachen. In spite of heavy air support, the Americans were not successful in breaking through the German defenses and linking up with Allied forces in the south. The Germans, using artillery, took advantage of the narrow front line to attack advancing American units.

Hobbs instructed his forces to outflank the Germans using two battalions to advance by an alternate route. The Americans stumbled upon an air raid shelter on October 15 that housed 1,000 civilians. The maneuver succeeded enabling the 30th and 1st Infantry Divisions to link up on October 16. Aachen was now encircled, but the Germans tried to break the surrounding ring of Allied forces.

On the afternoon of October 15, Wilck ordered a counterattack designed to halt American progress and stabilize German position in the center of Aachen. Ring’s SS troops attacked at dusk and the fighting raged for two hours before the Germans pulled back. Both sides suffered substantial casualties in the surge in fighting.

Wilck, who had moved his headquarters to the Hotel Quellenhof, issued a new directive to the defenders of the city. “We shall fight to the last man, the last shell, the last bullet,” he said. The hotel billiard room, beauty parlor, and children’s dining room were now defensive strongpoints. On October 18, the 3rd Battalion, 26th Infantry swept into Farwick Park and prepared to assault the hotel. American tanks and artillery began firing on the hotel at short range. Soldiers of the 1st SS Battalion repulsed several attacks on the building. To assist them, German forces nearby launched a strong counterattack that overran several American infantry positions. This relieved the pressure on the hotel for a short time. American mortar teams rained shells down on the German positions. In addition, an M12 advanced along Rolandstrasse followed by Sherman tanks and assault guns that fired left and right into the houses fronting the boulevard. The M12 put 30 rounds into the hotel, reducing it to a pile of rubble.

While the enemy hid in the hotel basement to escape the incessant American shelling, a platoon under 2nd Lt. William Ratchford stormed into the lobby. The American lobbed grenades through all of the entrances to the basement. When Ratchford procured machine guns for firing into the basement, the Germans decided that they had had enough. The Americans killed 25 Germans in the firefight. As the Americans moved through the hotel, they found large quantities of food and ammunition. On the second floor they came across a 20mm antiaircraft gun that the Germans had carried upstairs piece by piece and reassembled the crew-served gun.

On October 19, Corley’s men seized the Salvatorberg with little resistance. At the same time, the heights of Lousberg were being overrun by American forces. The Aachen-Laurensberg highway was soon cut by the same American forces. By nightfall on October 19, a part of the same force had occupied a chateau within 200 yards of the highway. In the chateau the Americans found stacks of ammunition and, to their disappointment, empty whiskey bottles scattered about the grounds. During the afternoon of the same day, the German commander, Wilck relayed Hitler’s order to the city’s garrison instructing the remaining troops to fight to the last man.

At that point, German resistance rapidly fell apart. Even though the battalion of the 110th Infantry was in a defensive position, it would join Daniels’ battalion in finishing off the city. Daniels’ men had seized the main railroad depot and were closing in on a nearby railway line that led to Geilenkirchen and divided the business district from the western residential sectors. After taking control of the Technical University, a strongpoint in the northwestern sector of the city, the battalion reached the western railroad tracks at sunset on October 20. The few remaining Germans were captured in the western and southwestern suburbs. Some of the German soldiers who had not been captured decided that suicide was their best option. A soldier would take off his boot crook his big toe around the trigger of his rifle, put the muzzle in his mouth, and pull the trigger. For them the horror of war was over.

In a vain attempt to raise morale, Wilck requested 15 Iron Cross First Class and 147 Second Class medals for the remaining 800 men defending a 600-square-yard perimeter around his bunker. Outside the bunker, the flames had mostly died down and the morning dawned bright, clear, and cold. Allied dive bombers pounded the narrow circle of Germans defending the bunker.

Corley and Daniels believed air support unnecessary at that point in the battle. Corley’s men moved down the Weyherstrasse where they found an abandoned German command center. Meanwhile, Daniels’ infantry advanced to the command bunker on the Rutscherstrasse and took it under fire. Corley was not going to sacrifice the lives of his exhausted infantrymen on a frontal assault against the bunker. He decided to bring up a 155mm gun. By noon it was in action, firing one shot after another into the defenses around the bunker from a range of less than 200 yards. It compelled the survivors to surrender. Wilck remained defiant, but it may have just been for show to Berlin. “All forces committed to the final struggle,” Wilck said in a radio message that night. “We shall fight on. Long live the Führer!”

Despite his bluster, Wilck wanted to end the fighting. But he faced a real dilemma in carrying out that objective. Two Germans who had previously tried to leave the bunker under a white flag had been shot in the confusion of battle. The answer appeared to be the use of American prisoners. The Germans asked for volunteers from among the Americans to help with the surrender. Staff Sergeant Ewart M. Padgett and Private First Class James Haswell, both of the 1106th Engineer Combat Group, volunteered to translate. When the two Americans came out from the bunker, they were greeted with small arms fire. An American rifleman soon motioned from a nearby window, directing the two men forward. Padgett motioned for the two German officers behind him to follow. At Corley’s headquarters, Brig. Gen. George Taylor, the 1st Division assistant commander, accepted the German surrender on October 22.

The Americans suffered 5,000 casualties in the protracted battle. The fighting had taken a severe toll on the 1st and 30th Divisions, which were depleted and would require rebuilding. They would not be in shape to advance to the Rhine River and participate in its crossing.

The Germans suffered a similar number of combat casualties and also lost the use of about 15,000 men who were taken prisoner by the Allies. Except for its famous cathedral, Aachen was mostly demolished in the street fighting. “The city is as dead as a Roman ruin, but unlike a ruin it has none of the grace of gradual decay,” said a visitor to the city soon after it fell to the Americans.

Aachen was securely in American hands. It had the distinction of being the first German city to be taken by an invading army in more than a century. The Germans offered various excuses for their failure at Aachen. They blamed superior Allied air power and artillery for their defeat.

The next chapter in the road to Berlin was a particularly bloody one. Once the Battle of Aachen was over, Hodges’ First Army was given the difficult task of capturing the Roer Dams east of the Hürtgen Forest. The dams could be used by the Germans to flood the valleys the Americans were hoping to use as part of a route to Berlin. Yet no American soldier had to be reminded that hundreds more German cities, towns, and villages needed to be taken before the Third Reich was no more.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments