By Blaine Taylor

April 1, 1939, was a red-letter day in the history of the reborn German Kriegsmarine for two key reasons. First, Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler presented the fleet’s chief, Erich Raeder, with an ornate, icon-studded Navy blue baton of office as the first grand admiral since the days of the Kaiser Wilhelm II. This was done with great ceremony and a gala luncheon afterward aboard the new battle cruiser Scharnhorst, anchored on Jade Bay in the former Imperial port of Wilhelmshaven. Second, the Kriegsmarine christened and launched the Third Reich’s newest and most modern battleship, the Tirpitz, on the same day. The Tirpitz, the last battleship the Third Reich would build, was the sister ship to the Bismarck. But the Tirpitz was heavier than the Bismarck. Moreover, it had the distinction of being the largest warship built in Europe up to that point in time.

The name of the new battleship paid tribute to Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who worked with the Kaiser to create Germany’s powerful and impressive High Seas Fleet, which served and protected the empire from 1898 to 1918. Tirpitz was a gruff old salt who sported a Neptune-like pointed beard. When the Kaiser refused to allow him to command the fleet during the Great War, he resigned in a huff in 1916. Turning his attention to politics, he founded the pro-war Fatherland Party and was subsequently elected to the German Reichstag as a deputy. Sadly, he was not alive to see the ship that bore his name slide into the water in 1939 for he had died nine years earlier. But his daughter, Ilse von Hassell, was present. She was on hand for the April 1 ceremony in which Hitler named the mighty vessel honoring her late father and she christened it.

Just two months before Hitler had authorized Raeder to enact his ambitious Plan Z. The plan entailed the expansion of the Kriegsmarine so that it could successfully challenge the naval power of the United Kingdom. The ambitious plan called for a naval force composed of 10 battleships, 15 pocket battleships, four aircraft carriers, 250 submarines, and more than 100 cruisers and destroyers.

The Kriegsmarine had sketched out the ambitious plan the previous year. The grandiose German super fleet envisioned by Hitler and the Kriegsmarine would not be ready until 1948. But the British declared war on September 3, 1939, on Nazi Germany before the Kriegsmarine had made any tangible progress toward the plan’s goals.

At that point, Raeder had only two 15-inch-gun battleships, three 11-inch-gun pocket battleships, two 11-inch-gun battle cruisers, two 8-inch-gun heavy cruisers, six 6-inch-gun light cruisers, 34 destroyers, and 57 U-boats. The Bismarck had launched on February 14, and the Tirpitz on April 1.

The Germans never built any aircraft carriers with which to counter the French and British fleets. The odds against the Germans at sea increased dramatically when the Soviet Union and United States entered the war in 1941. Raeder faced an early sea war that he neither expected nor wanted, but Hitler showed little concern for grand admiral’s wishes.

The Tirpitz displaced 41,700 tons, was 828 feet long, and had a beam of 119 feet and a draft of 36 feet. Three geared steam turbine engines powered the Bismarck-class battleship. She had a dozen superheated boilers that when working in tandem produced a maximum speed of 30 knots. Her wartime crew numbered 108 officers and 2,500 enlisted sailors.

The Tirpitz’s main armament was her eight deadly 15-inch guns, which were housed in four turrets. One pair of the 15-inch guns was located forward and another pair was located aft. The guns had a maximum range of 22.4 miles. The fore turrets were named Anton and Bruno, and the aft turrets were named Caesar and Dora.

The Tirpitz’s secondary armament consisted of a dozen 5.9-inch guns housed in six double turrets, three of which were located on each side amidships. For protection against incoming enemy rounds, the Tirpitz had belted armor plating that was 13 inches thick. The battleship’s turrets, gunnery control, and command posts were individually protected with additional armor; however, the antiaircraft positions lacked overhead cover. In addition, she also boasted two quadruple 21-inch torpedo mountings on deck.

Installed foreward, foretop, and aft, the Tirpitz featured Model 26 search radar rangefinders, as well as a Model 30 on her topmast and a Model 213 fire-control radar unit aft, which complemented her 4.1-inch antiaircraft gun rangefinders.

To meet her aerial reconnaissance needs, the Tirpitz possessed four Arado Ar-196 seaplanes. The crew launched the single-wing seaplanes using a double-ended, 34-yard-long telescoping catapult. The seaplanes were armed with machine guns and cannons, and also could carry one 110-pound bomb to strike enemy submarines caught on the surface. The crew retrieved the seaplanes from the ocean surface by hauling them back on board by crane.

The Royal Navy viewed the Tirpitz as a menace not only to its warships, but also to merchant vessels that brought food and ammunition to the British Isles. From her Baltic Sea home port, the Tirpitz could intercept Allied convoys bound for Murmansk in the Arctic Circle. Because of these threats, the British Royal Navy and Royal Air Force had to delegate a large complement of naval and air resources to counter the threat the Tirpitz posed. This was known as the fleet-in-being concept by which a powerful warship or naval force poses a threat without ever leaving port.

In the aftermath of the sinking of the Bismarck on May 27, 1941, the Kriegsmarine was reluctant to send the Tirpitz on raiding missions in the North Atlantic Ocean. Such missions became even less practical in the wake of the British commando raid against St. Nazaire on March 28, 1942, in which the port’s dry dock was severely damaged.

In light of such setbacks, Hitler insisted that the Tirpitz deploy to Norwegian waters to shore up the German-occupied country’s maritime defenses. Hitler’s rationale was that the Tirpitz could help defend the Norwegian coast against an Allied invasion. Despite evidence to the contrary, he firmly believed that the Western Allies would attempt a seaborne invasion of Norway. He even feared a possible invasion of northern Norway by the Soviet Union.

The first attacks by the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm occurred while the Tirpitz was under construction at Wilhelmshaven, but she was not hit. The Tirpitz was commissioned on February 25, 1941. British Royal Air Force aircraft failed to score any hits on the Tirpitz while she was undergoing extensive trials and crew training in the Baltic Sea.

As captain of the Kaiser’s yacht Hohenzollern before World War I, Raeder had firsthand knowledge of the location of many of the protective Norwegian fjords to which he ordered Tirpitz to set sail on January 14, 1942. But the Germans did not know that the British were able to decipher their radio traffic through Enigma machines.

Captain at Sea Karl Topp, the Tirpitz’s commander, pronounced her ready for combat operations on January 10, 1942. Four days later she departed Wilhelmshaven bound for Trondheim. Although the British knew that she had sailed, inclement weather conditions in England prevented any aerial sorties against her while she was en route to Trondheim.

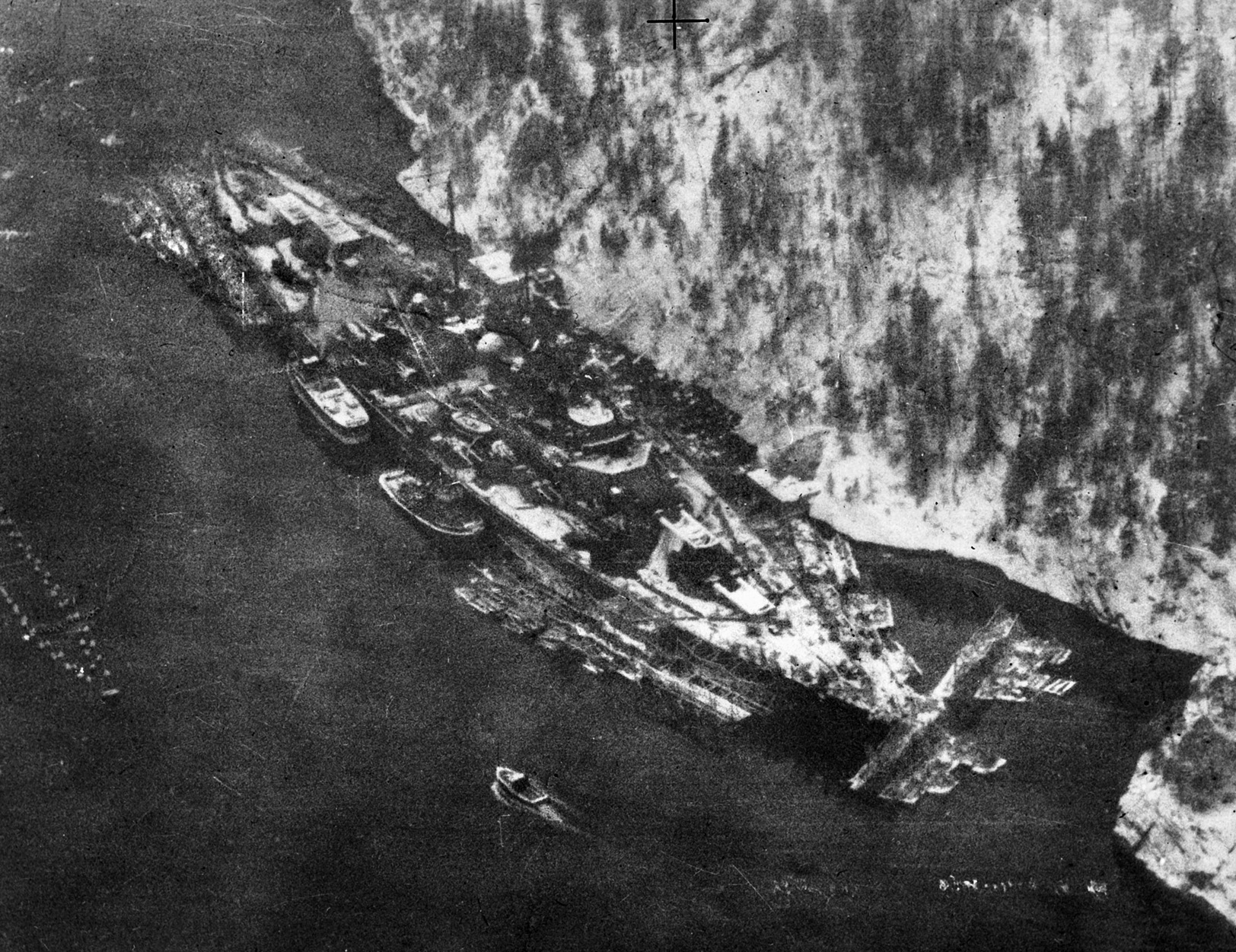

The Tirpitz dropped anchor at Faetten Fjord on Trondheim’s eastern end on January 16, 1942, where she was duly discovered eight days later by a startled Forward Air Arm pilot who initially mistook the behemoth battleship for an island.

Besides her own powerful guns, Tirpitz was protected by multiple antiaircraft batteries ashore and from 100 yards away by sunken steel antisubmarine and antitorpedo netting. The Germans also had Junkers Ju-88 fast bombers and Junkers Ju-87 dive bombers stationed on nearby airfields.

The shore-based antiaircraft gunnery defenses were aided by heavy booms installed in the fjord mooring’s mouth. To keep the crew both busy and in good physical shape, Topp dispatched tree-cutting details ashore to provide camouflage on-deck for the huge vessel.

In February 1942, Tirpitz had her first real combat jaunt at sea when she participated in a deceptive sortie to draw away Royal Navy attention from the coming English Channel dash of Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen returning to German home ports.

Operation Cerberus was a successful joint Luftwaffe-Kriegsmarine episode of good cooperation between the two normally rival services. In concert with both destroyers and torpedo boats, the following month the Tirpitz had orders to begin assaulting both inbound and outgoing Allied convoys in Operation Sports Palace, but the enemy was forewarned by Engima intercepts that helped to foil the mission.

On March 9, 1942, the RAF’s Forward Air Arm conducted a series of aerial torpedo attacks against the Tirpitz that resulted in the wounding of three sailors. The RAF lost two aircraft to the Tirpitz’s antiaircraft guns.

Back at Trondheim on March 30-31, 33 Halifax bombers failed to score a single hit at the cost of five bombers. Follow-up raids conducted on April 27-28 by Avro Lancaster and Handley Page Halifax bombers resulted in the loss of seven more bombers without any hits on the battleship.

A particularly embarrassing episode for the Allies occurred in regard to Allied Convoy PQ-17, which departed Iceland bound for Archangel on June 27, 1942. Based on deciphered messages that the Tirpitz and other surface vessels were going to intercept the convoy, the British Admiralty ordered its escorting vessels and the convoy itself to disperse. Ironically, the Tirpitz had never sailed because the German High Command changed its mind and cancelled the raid. In the ensuing action, German aircraft and U-boats sunk 21 of the 34 merchant vessels. Shortly afterward, the Tirpitz received a general overhaul at Trondheim in which the Faetten Fjord defenses were doubled and a caisson was constructed around the stern to allow workers to replace the ship’s rudders.

The British attempted to sink her in October 1942 with two British Mk 1 Chariot torpedoes deployed by frogmen. Launched from a fishing boat in Norwegian waters, the Chariots broke free from their tow-hooks in a gale and the operation was cancelled. After the Tirpitz rudder overhaul was completed in early January 1943, she underwent sea trials to ensure the ship’s steering was in working order.

Hitler replaced Raeder with Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz on January 30, 1943. The catalyst for the move was Hitler’s lack of confidence in the Kriegsmarine’s handling of its surface ships following the Battle of the Barents Sea on December 31, 1942. The battle occurred during a raid by German cruisers and destroyers against Allied Convoy JW 51B bound for Murmansk.

During the unsuccessful raid, the British light cruiser Sheffield sank the German destroyer Friedrich Eckoldt. Hitler demoted Raeder to admiral inspector and decreed that from that point forward the Kriegsmarine would have to rely almost entirely on U-boats for convoy raiding.

However, on September 7, 1943, Hitler allowed the Kriegsmarine to send a task force composed of the Tirpitz, Scharnhorst, and nine destroyers to bombard the Free Norwegian naval base at Spitsbergen for the purpose of destroying Allied weather installations on the island. The mission was the only time the Tirpitz fired her main guns in action. She fired 52 main battery shells and 82 rounds from her secondary guns. The following day the Kriegsmarine landed a battalion of German soldiers who captured the installations and took 74 prisoners. The operation was a resounding success. Hitler could rejoice that his expensive heavies had at long last achieved a noteworthy success.

Before the month was over, the British Admiralty opted for an attack with its newly designed X-Craft midget submarines in which they would drop deadly mines underneath the Tirpitz to take advantage of its thin hull armor.

The British sent 10 of the midget submarines into the area during a five-day period beginning September 20, 1943. Eight reached the target area after two days. Three succeeded in breaching the Tirpitz’s outer water defenses. Of these, one was sunk by German gunfire and depth charges and two succeeded in depositing their mines.

One of the mines exploded abreast of gun turret Caesar, and a second blew up off her port bow, rupturing an oil tank, tearing up some armor plating, making an indentation in the hull, and buckling double-bottom bulkheads.

The crew contained the interior flooding and repaired mechanical damage; however, the Dora gun turret was torn from her rotating bearings and could not be restored right away due to a lack of heavy cranes. The battleship also lost two of her seaplanes. The German repair ship Neumark restored her to combat readiness by April 2, 1944.

The next day, 40 Barracuda dive bombers escorted by 40 fighter aircraft, attacked the Tirpitz in two waves while she was on sea maneuvers. They scored 15 direct hits at the cost of one aircraft.

The armor-piercing bombs did not penetrate the Tirpitz’s armor, but her superstructure was damaged. Casualties amounted to approximately 500 killed and wounded. The damage to the battleship consisted of the loss of a pair of 5.9-inch turrets and two more Arado Ar-196 floatplanes. The two near misses also caused flooding via holes in one side produced by shell splinters.

By June 1944 the Kriegsmarine could no longer send the Tirpitz to perform surface missions due to a lack of fighter aircraft cover; nevertheless, the Tirpitz was again deemed to be seaworthy by her own engines and enhancements were made to her antiaircraft capabilities.

The British conducted five successive Fleet Air Arm attacks on the Tirpitz during the summer of 1944 that either failed or had to be scrapped. Because of the Royal Navy’s inability to destroy the Tirpitz from the air, the mission was reassigned to the Royal Air Force Bomber Command.

By September 1944, RAF Bomber Command had opted to use the Tallboy earthquake bomb. The 12,000-pound medium-capacity bomb had a proven ability to penetrate reinforced concrete and had the potential to inflict underwater damage on a large ship at anchor. Bomber Command also planned to drop JW mines designed to rupture the vulnerable undersides of the hull, which were only protected by armor plating three-quarters of an inch thick.

Operating from a forward base at Yagodnik in the Archangel region of the Soviet Union, the first Tallboy and JW mine attack was carried out by 23 Lancasters, 17 of which carried one Tallboy each and six of which carried two JW mines each. One of the Lancasters scored a direct hit with its Tallboy on the ship’s bow. The bomb penetrated the ship, going clear through it from deck to keel before exploding at the bottom of the fjord.

Hundreds of tons of water flooded the bow, rendering the battleship unseaworthy and limiting its speed to a maximum of 10 knots. In addition, the concussive shock damaged the fire-control equipment. The Kriegsmarine High Command opted to patch up the hole as quickly as possible so that the Tirpitz could be moved from Alten Fjord south to Tromso to be farther away from the Russians, who were threatening the northeastern tip of Norway. On October 15 the Tirpitz made her final voyage, sailing 200 nautical miles to her new location.

On September 29, the British struck again with a flight of 32 Lancasters. An underwater detonation in close proximity to the battleship damaged her port rudder and shaft, which resulted in major flooding.

The Kriegsmarine then established the Tirpitz’s final defensive posture and braced for another aerial bombardment. They built a large sandbank around the ship to prevent capsizing, installed more antitorpedo netting, and reduced the crew to 1,900 officers and men.

On November 12, 1944, RAF Bomber Command executed Operation Catechism. Thirty Lancaster heavy bombers rumbled into the fjord at Tromso. The Tirpitz’s main guns roared to life, but they failed to disperse the bombers. Each of the bombers carried one 5.4-ton Tallboy bomb. The British heavy bombers scored three direct hits.

The first bomb, which landed between the gun turrets Anton and Bruno, failed to explode. A second bomb struck the vessel between its aircraft catapult and the funnel amidships. It produced enormous damage to the hull. A large hole opened up where the belted armor had been completely destroyed. The third bomb struck on the port side of gun turret Caesar.

The hit amidships led to an order to abandon ship. An internal explosion occurred 18 minutes later in the Caesar turret that blew off its roof. Debris from the explosion rained down on many of the sailors swimming to shore, producing significant casualties.

The Tirpitz capsized with her superstructure lodging itself into the sand bed. The crew launched a rescue mission to save those inside. Men used blowtorches to cut through the hull. Because of their efforts, 82 men were saved.

The Luftwaffe was roundly blamed for the sinking of the ship on the grounds that it failed to furnish sufficient air cover with fighter aircraft. Of the 1,900 crew, 1,200 were killed, wounded, or missing. The crew members who were ashore during the attack were truly fortunate.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments