By Glenn Barnett

In March 1942, General Douglas MacArthur was ordered out of the doomed Philippines by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to organize the defense of Australia. “Must I always lead a forlorn hope?” he lamented.

The Defense Of Australia

Most of the Australian Army was away fighting in North Africa, and only local militia was available to stop the rapidly advancing Japanese. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill reluctantly dispatched veteran Australian troops from the Egyptian desert to defend their homeland, but they would not begin to arrive until May.

Two divisions of American National Guard troops were on their way, but straggling in ever so slowly. The 41st Division of Oregon Guardsmen had been slated for Australia as early as 1940 but had not yet arrived in force. The 32nd “Red Arrow” Division of Wisconsin and Michigan Guardsmen came as a unit in May of 1942.

Two divisions of American National Guard troops were on their way, but straggling in ever so slowly. The 41st Division of Oregon Guardsmen had been slated for Australia as early as 1940 but had not yet arrived in force. The 32nd “Red Arrow” Division of Wisconsin and Michigan Guardsmen came as a unit in May of 1942.

The United States had not yet fully mobilized, and Washington had no more troops to give. No more divisional-strength units would arrive in Australia for another year. MacArthur would have to make do with the forces at hand, a smattering of planes, and almost no naval support.

Invasion Looms With Japan’s Control Of Air And Sea

On February 19, even before MacArthur arrived, the Japanese bombed the Australian city of Darwin, the first of 64 such raids. With Japan in command of both air and sea, invasion seemed a very real possibility. What training the militia and Guardsmen had received was defensive in nature. No jungle training was authorized or envisioned.

For the 32nd it was an exasperating time. Their commander, Regular Army, West Point-trained Maj. Gen. Edwin F. Harding, would say that between February and November 1942 they were always “getting ready to move, on the move, or getting settled after a move.”

New Guinea Provided Last Shield

The island of New Guinea stood like a giant shield of mountainous jungle between Australia and the all-conquering empire of Japan. The enemy had already seized the western half of the island from the Dutch. One by one they captured primitive prewar airfields on the northern shore of Australian-controlled Papua New Guinea. Only Port Moresby on the southern shore still had an Australian presence.

In May, the Japanese decided to capture Port Moresby. A powerful fleet was assembled at the great naval base of Rabaul on New Britain and was dispatched to escort the troop transports that would occupy the remainder of the island. The Americans, however, had deciphered the Japanese naval code and hurried their own scratch force to intercept them in the Coral Sea. Both sides sustained terrific damage in the first naval battle in history where neither side came within sight of the other. The tactical draw at Coral Sea was a strategic victory for the Americans, forcing the vulnerable transports back to Rabaul. New Guinea was temporarily saved.

Aussie Militia Arrives Too Late

In June, MacArthur ordered the Australian militia at Port Moresby (the army was only just arriving in Australia from North Africa) to advance across the Owen Stanley Mountains toward the north-shore towns of Buna and Gona. These two lonely outposts were the sites of prewar missionary activity and some coconut plantations. They were unoccupied by the Japanese. That soon changed.

Advanced patrols of the Australian militia arrived at Buna only to see Japanese transports off-loading troops to occupy the two settlements. The militia rapidly retreated up the Kokoda Track over which they had come. A treacherous trail, the Kokoda Track wound through the jungle and mountains of New Guinea connecting north and south by the slimmest of red clay footpaths through a misty mountain pass at an elevation of 6,000 feet. The Japanese set out in hot pursuit.

Advanced patrols of the Australian militia arrived at Buna only to see Japanese transports off-loading troops to occupy the two settlements. The militia rapidly retreated up the Kokoda Track over which they had come. A treacherous trail, the Kokoda Track wound through the jungle and mountains of New Guinea connecting north and south by the slimmest of red clay footpaths through a misty mountain pass at an elevation of 6,000 feet. The Japanese set out in hot pursuit.

The Australians began a desperate holding action against a force of jungle-trained, battle-hardened Japanese veterans who knew their business. A revered warrior led them. General Tomitaro Horii was a veteran of the fighting in China. He was beloved by his men. The exhausted Aussies were continually outflanked and overrun along the jungle trail by a numerically superior enemy equipped with mortars and field artillery. At the end of the chase barely 300 ragged, filthy, exhausted survivors faced an enemy of 5,000 determined Japanese.

Reinforcements Begin To Arrive

During the pursuit, an event took place that would cast a huge shadow on the battle for New Guinea. American Marines landed at nearby Guadalcanal.

With the veteran 7th Division now home from Egypt, two brigades were flown to Port Moresby on every aircraft, military and civilian, available in Australia. As their advanced elements reinforced the militia, they, too, were thrown back. By September 17, the Australians were forced back to Imita Ridge, the last hill before Port Moresby and the sea. Digging in once again, the Australians were bombed almost daily. It seemed that the climactic battle for the town would come soon. No one knew it at the time, but Imita was the high-water mark of the Japanese empire.

While the two brigades of the Australian 7th Division were contesting the Kokoda Track, a third brigade was sent to hold Milne Bay on the very eastern tip of New Guinea. It was a good thing, too, for the Japanese had decided to occupy the bay and use it as an advanced base against Port Moresby. Japanese troops went ashore on the outskirts of the Australian position on August 25. Tanks were landed to support the Japanese drive, but these did little good in the bay’s soft sand and had to be abandoned. The Aussies beat back several attacks and forced the Japanese to withdraw their forces on September 7.

Tables Are Turned On Japanese

Suddenly General Horii’s position at the southern end of the Kokoda Track seemed very vulnerable. He had a long and tenuous supply line fed almost exclusively by native labor brought from Rabaul. Most of the supplies for Horii’s army were carried on the natives’ backs. Whenever the opportunity arose, the reluctant carriers would melt away into the jungle. Meanwhile, much of the available Japanese air and naval resources were diverted to contest the American occupation of Guadalcanal. Tokyo ordered Horii to retreat.

Frustrated at the futile sacrifice of his soldiers, Horii reluctantly obeyed. The tables were turned. The Australians became the pursuers and outflanked the rear guard of Japanese defenders all the way back to Buna. In the confusion, Horii drowned while attempting to cross a rain-swollen river.

Hasty Dye Job Contributes To Troops’ Misery

While the Australians still had their backs to the sea at Port Moresby, MacArthur finally committed American troops. Two regiments of the 32nd Division were summoned to New Guinea. The 126th and 128th regiments arrived without their artillery and most of their equipment.

Company E of the 126th was flown to Port Moresby on September 15.

The night before leaving Australia, their khaki uniforms were hastily “jungle dyed” by a Brisbane dry cleaner. The mottled camouflage was not yet dry when the men put them on for the flight. The dye job sealed the fabric and prevented the material from breathing. The hasty camouflage job led to skin ulcers in the jungle and added to the misery of the troops. They already had an inkling of what was to come. One trooper wrote in his diary, “New Guinea weather is hotter than the lower story of hell.”

On the prewar maps of New Guinea there was another native trail east of Kokoda. It was called the Kapa Kapa Track, and it wound over the Owen Stanley Mountains to the north shore of the island. To the armchair generals in Australia, it looked like men using the trail could cut off the Japanese retreat.

Inhospitable Environment Tests American and Australian Troops

On October 6, 250 men of 2nd Battalion, 126th, supported by a hundred native carriers (called “fuzzy wuzzys” by Americans and Australians) started up Kapa Kapa. It was a disaster from the start. There really was no trail after the men reached the foothills of the Owen Stanleys.

This area of New Guinea was largely unexplored, and the men of 2nd Battalion had to create their own path. Jungle, rain, mud, leeches, rats, insects, sheer cliffs, and deep valleys all wore at the men. The natives soon deserted, and the way was littered with the detritus of an army disintegrating on the march. A week later the 900 additional troops of 2nd Battalion followed.

Almost everyone suffered from the chills and fever of malaria and dysentery. In frustration, many men cut the seats out of their pants. Boots rotted off their feet, and uniforms became tattered, muddy, and bloodstained rags. They had to survive on cold, air-dropped rations. It rained too often to build cooking fires. Unlike the 6,000-foot pass of the Kokoda Track, Kapa Kapa crossed a mountain peak with the chilling name of Ghost Mountain at 9,000 feet. Wrote one man, “If we stopped, we froze, if we moved we sweated.”

Japanese And Americans Race To Build Airfields

No sooner had the overland marchers disappeared into the jungle than scouts reported that airfields could be built north of the mountains. There were several promising locations on flat plains covered with tall kunai grass near Buna itself. Engineers were sent around New Guinea by boat and took up the task immediately. The 2nd Battalion took 42 days of living hell to cross the mountain range. They were met by the rest of the 126th and the 128th which had flown to Buna in just 42 minutes.

The Japanese, meanwhile, had retreated to the Gona/Buna area and dug in. The engineers they had brought from Japan to build airfields at Port Moresby set to work building defenses on an 11-mile-long coastal strip. Thick coconut logs and oil drums filled with sand were cleverly hidden in the fast-growing jungle. The fortifications would extend into a three-mile-deep area. The right flank was secured on impenetrable swamp, and the left flank rested on the ocean at Cape Endaidere.

American Service Rivalries Hamper Operation

The water table along the coast was too high to build fortifications underground, but even so, the pillboxes, bunkers, machine-gun nests, and snipers’ lairs were so well camouflaged that Allied aircraft overhead and patrols on the ground thought the area to be lightly defended. This battle was thought to be easy.

In fact it would be a bloody mess. Never in American history would interservice rivalry exact such a heavy toll of American life. MacArthur feuded continually with the U.S. Navy. He demanded ships, planes, and men from Washington. The Navy would not send him a single destroyer to soften up Japanese positions nor a single landing barge to facilitate delivery of supplies and troops. They argued that the Japanese had air superiority in New Guinea, making naval operations dangerous.

In fact it would be a bloody mess. Never in American history would interservice rivalry exact such a heavy toll of American life. MacArthur feuded continually with the U.S. Navy. He demanded ships, planes, and men from Washington. The Navy would not send him a single destroyer to soften up Japanese positions nor a single landing barge to facilitate delivery of supplies and troops. They argued that the Japanese had air superiority in New Guinea, making naval operations dangerous.

Meanwhile, the Navy had its hands full at Guadalcanal where it had neither naval or air superiority. The Navy was not about to siphon off precious resources to help a stubborn, imperious MacArthur. Buna was to be exclusively an Army show.

MacArthur Improvises Own Navy

Ironically, the same situation existed in the Japanese military. The Army was responsible for New Guinea, and the Navy was tasked with retaking Guadalcanal. The Japanese High Command, like the Americans, viewed Guadalcanal as the real battle. They knew of the importance that Americans were placing on the Solomon Islands and were determined to wrest Guadalcanal from the Marines. New Guinea was rapidly becoming a sideshow.

There was one striking contrast between the two concurrent battles. On Guadalcanal, the Americans defended a thin coastal strip around Henderson Field, while the Japanese were forced to operate in thick, malarial swamps and jungle. At Buna, the opposite was true.

MacArthur would have to improvise his own navy. The Allies managed to commandeer a few fishing trawlers, yachts, and a Japanese landing boat abandoned at Milne Bay. These were pressed into service to carry supplies and troops from Milne to the coast near Buna. During the second run on November 16, the flotilla was shot up and sunk by marauding Zero fighters. The Allies lost 81mm mortars, ammunition, artillery rounds, .50-caliber machine guns, rations, and medical supplies. Soon they would be desperately missed. Almost all supplies would have to be delivered by air, and at the time there were precious few planes available.

“The Artillery In This Theater Flies”

The Air Force was part of the problem too. General George Kenney was in charge of the Army Air Corps in Australia. He was also a trusted member of MacArthur’s staff. Kenny, like German Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring at Dunkirk, assured his master that air power alone could easily defeat Japanese defenses. “The artillery in this theater flies,” he boasted. Traditional artillery would not be needed. Only one artillery piece, a 105mm howitzer along with 200 rounds, would arrive at Buna. The Australians would have eight pieces of a smaller The 105mm gun was parked at a convenient location and never moved during the course of the month-long battle. The 200 rounds were quickly used up, and the gun stood idle. Additional rounds had been sent on one of the barges that were sunk by the Zeros.

Poor air-ground communication was another problem. American bombers could not tell where the camouflaged positions of the enemy were located and dropped their bombs ineffectually, sometimes killing their own men. American planes strafed American troops so often that the men on the ground began to fire back. Then, too, MacArthur’s obsessive secrecy would keep Buna off the front pages at home, while Guadalcanal captured the American imagination.

Attack On Buna

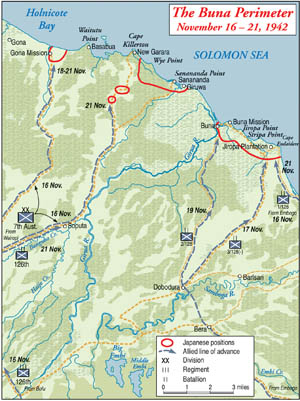

While the outcome for the Marines in the Solomons was still in doubt, the Army began its attack on Buna on November 19. The veteran Australians of the 7th Division, with their supporting militia, took the left flank and attacked toward Gona over a narrow native path through the jungle.

On the right, the Americans were divided into three attacking forces. The 1st Battalion of the 128th attacked up the coast. The 126th Regiment, minus the 2nd Battalion which was still on Kapa Kapa Track, attacked along a jungle path toward Buna Mission, which was also called Government Station. This attack group would become known as Urbana Force. The 3rd Battalion, 128th attacked between the other two on another jungle track toward two bombed-out airstrips. They were called the Warren Force.

The Japanese were ready. The approaches to the coast were along narrow jungle trails that funneled the Allied soldiers through malarial swamps directly into the sights of hidden Japanese guns. It rained the entire first day, making air support impossible and ground action miserable. The attacking forces ran into heavy fire from an enemy they could not see.

Stealth Japanese Rifle Confuses Americans

The standard Japanese infantry weapon was the Arisaka Model 38 rifle. It was heavy and long but made an excellent jungle weapon. Its awkward length meant that the muzzle did not flash upon firing as did the American M-1. The Japanese also had a superior smokeless powder that did not announce the shooter’s position. The canopy of jungle muffled sound and made it difficult to know where a shot came from. The Arisaka used a .25-caliber round, which was also used by Japanese machine guns, making resupply easier.

The Japanese soldiers rotated their weapons during a fight so that one machine gun seemed, to the inexperienced Guardsmen, to be firing from everywhere. The first attack fizzled out with a mass of casualties.

The second day was worse. Australian General Thomas Blamey, the New Guinea Force commander, convinced MacArthur that his 7th Division was facing more of the enemy than the Americans. MacArthur authorized the 126th Battalion to be pulled out of the line and moved to support the Australian assault on Gona. They would be under Australian command.

MacArthur Out Of Touch With “Cost”

Harding was furious. He lost nearly half his force with this move and protested vehemently. He was compelled to bring up his reserve, the 2nd Battalion, 128th, to take the place of the departed 126th.

Harding ordered another attack on November 20. It also failed miserably. He then convinced his superiors to have the Australians give him back at least a part of the 126th. He was given the sick and exhausted Kapa Kapa veterans who had just arrived.

On November 22, Harding received a message from MacArthur, now based in a house at Port Moresby nicknamed the “Ivory Tower.” The message said that Harding was to press the attack the following day “regardless of cost.” MacArthur never once visited the front and had no real idea of what “cost” meant to the men who had to pay it.

The next day saw renewed attacks against the unseen Japanese positions. The assault was supported by mortars and the 105mm howitzer. After a little progress, the attack was called off because the men were again taking tremendous casualties from unseen enemy positions.

American Supply Lines Strained

Attacks were resumed on November 26, Thanksgiving Day, but ran into the same problems. Unseen fire, losing direction in the swamps, Japanese air attacks, and jungle diseases all contributed to the confusion, frustration, and misery of the men.

The long supply line was tenuous as well. There were not enough C-47 transport aircraft to bring in all the supplies that were needed. Those supplies that did land at the rough-hewn airstrips had to be carried by hired “fuzzy wuzzys” for 30 miles or more through kunai grass and swamp to the front. The natives refused to enter areas that came under enemy fire, so soldiers lugged the bulky packs the rest of the way to their intended destinations.

There was a growing sense of despair at Buna and at the “Ivory Tower” too. MacArthur wanted no more “forlorn hopes.” He wanted an Army victory at Buna before the Navy could win its battle at Guadalcanal. He kept pushing his commander on the ground to aggressively attack the enemy. While the men of the 32nd Division were fighting and dying with no artillery support, dubious air support, incurable diseases, and insufficient supplies, they were getting a reputation in the rear as cowards.

MacArthur Yanks Harding

On November 30 MacArthur sent his corps commander, Robert Eichelberger, to relieve and replace Harding. It must have been an uncomfortable meeting. The two men had been classmates at West Point and had known each other for most of their military careers. Harding returned to Port Moresby where MacArthur comforted him and sent him to Australia for rest, promising him a post when he returned. Harding never went back to New Guinea. In Australia, he was ordered home. MacArthur, it seemed, did not like confrontation.

Eichelberger took stock of the situation and was shocked by the ailing and dispirited men he found at the front. In one company, every single man was running a fever. Organization had broken down with so many squads thrown into the fight piecemeal. He pulled his forces back and regrouped. His staff officers performed heroic service in increasing the delivery of supplies and reinforcements, support that had been denied to Harding. The offensive renewed on December 5.

Hopes were high because some Bren gun carriers had been barged in and sent to Warren Force in lieu of tanks. However, they were all knocked out within 20 minutes of fighting.

Refugee From Nazi Germany Leads Heroic Assault

That December day saw an American platoon fighting its way to the beach between Buna Village and Buna Mission and cutting the Japanese position in half. The assault was led by Staff Sgt. Herman Bottcher. Born in Germany, Bottcher had left his homeland when Hitler came to power. A dedicated anti-Nazi, he had fought for the Loyalists in Spain, and his battle experience was valuable at Buna.

With one machine gun, Bottcher and his men held off several Japanese counterattacks over the next few days until his position was secured. Eichelberger was so impressed that he awarded Bottcher a Distinguished Service Cross and a battlefield promotion to captain. Two years later, as a major, Bottcher was killed in the Philippines.

By December 9, the Allies had scored their first real victory when the Australians captured Gona. Australian Lt. Col. Robert Honner radioed to his brigadier, “Gona’s gone!” This narrowed the front and allowed the Allies to concentrate their forces to reduce the remaining strongpoints.

Newly Arrived Flamethrowers Fizzle

About that time the first flamethrowers arrived on the scene. Again hopes were high, but they proved to be as useless as the Bren gun carriers. They dribbled fire instead of shooting it. These early models of the later successful flamethrower proved more dangerous to their operators than the enemy.

Mortars continued to be the only effective artillery. When the battle was over, captured Japanese diaries revealed that it was the mortars that they feared most. However, the 32nd had to rely primarily on rifles and grenades to flush out entrenched enemy positions.

Mortars continued to be the only effective artillery. When the battle was over, captured Japanese diaries revealed that it was the mortars that they feared most. However, the 32nd had to rely primarily on rifles and grenades to flush out entrenched enemy positions.

Fighting wore on continuously for three weeks, and both armies were exhausted. The Japanese had greater supply problems than their opponents. Army Air Corps B-25 Mitchell bombers began to scour the seas for Japanese ships, effectively keeping them at bay. The Japanese Navy lost several destroyers and transports trying to reinforce troops at Buna. These losses were suffered at a critical time when scarce resources were also needed to support Guadalcanal. The Japanese Navy then refused to risk more ships to supply the trapped men on New Guinea.

Airstrip and Roads Improve Allied Standing

Meanwhile, the Allied supply situation was improving. Engineers completed an airstrip at Dobodura just eight miles from Buna. They also worked behind the lines building roads and bridges for jeeps to make it easier to bring in supplies and carry out wounded.

Battlefield casualties were taken from aid stations just behind the front to portable field hospitals, sometimes just 500 yards behind the front lines. The portable hospital, a new innovation, was designed to be easily packed up and moved by its own personnel. They would evolve into the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (M.A.S.H.) units of the Korean War.

The tide was turning in favor of the Allies. However, the men who were suffering from malaria, dysentery, jungle rot, torrid heat, incessant rain, and vicious wounds did not fully comprehend this fact. The 2nd Battalion, 126th, which had been marching or fighting since 1,150 of them set out on Kapa Kapa Track in early October, was down to 150 men. The pitiful survivors had not changed their clothes in all that time.

Japanese Stack Their Dead For Sandbags

As bad as it was for the Americans and Australians, it was worse for the Japanese, who suffered the same maladies plus malnutrition. They had almost no resupply, no place to evacuate their wounded, and barely any medical facilities left. At Gona, the advancing Australians found dead Japanese piled up and used like sandbags to protect bunkers. The bunkers reeked so badly that the living Japanese still firing from them wore gas masks.

Kirkwood Adams, a gunner on a B-17 Flying Fortress bomber, recalled the battle: “We used to fly up to Buna every day. That was a real mess. We went in low. It was terrible—you could tell that from the air. I’m glad I wasn’t in it. It looked like the surface of the moon. Bomb craters all over—just stumps of trees left. There was total devastation. Things were so uncoordinated then. I think we bombed our own troops as often as we bombed [the enemy]. You couldn’t see any terrain lines. They were fighting so close.”

Victory Declared Prematurely In Buna

On December 14, Urbana Force attacked Buna Village. They found it deserted. The Japanese had melted into the sea and attempted to swim to the stronghold of Sanananda to the west. MacArthur’s headquarters issued a statement that Buna had been taken. It was duly reported in bold headlines in newspapers back home. Only at the bottom of the story was it noted that Buna Mission, the real military objective, still held out.

By now eight light tanks and their Australian crews had been shipped by sea to the front and brought up to the Duropa coconut plantation on the Japanese left. It was thought that the tanks might be used to good effect on this hard, sandy surface. On December 18, seven tanks jumped off to the attack, taking the Japanese by surprise. Three of the tanks were knocked out, but the others, with American infantry of Warren Force in support, crushed the enemy’s left flank, advancing all the way to Cape Endaidere. The noose was tightening.

American Marines had begun their offensive on Guadalcanal the previous day. The race was on.

On Christmas Eve, Warren Force crossed a swampy creek under continuous fire. They were supported by four tanks, but hidden antiaircraft guns quickly destroyed three of them and the attack stalled.

Quick Victory Was All That Mattered

General Eichelberger pushed his men so hard that the informal name for the Allied cemetery at Buna became “Eichelberger’s corner.” The general was under a great deal of pressure from MacArthur to win the battle or be sacked like Harding. History would frown on the Army brass for its impatience. Many lives were lost needlessly by repeated hasty and unsupported attacks, but at the time quick victory was all that mattered. Attacks were ordered on Christmas Day.

That night, the Japanese received their last delivery of supplies from a submarine. For a long while these were the only vessels that could sneak through the cordon of American bombers. It was much too little and much too late.

The Allied troops were beginning to see a disturbing trend. Japanese soldiers from generals to privates were refusing to surrender. They would die to the last man rather than be taken prisoner. A doctor at a portable field hospital within earshot of the front spent almost two years in New Guinea and never saw a living Japanese soldier, let alone treat any.

Buna Airfield Captured

By December 29, Warren Force had captured the old airfield at Buna. That day saw the last Japanese counterattack. Twenty of them rushed the Americans in their positions at the airstrip and managed to kill 15 Americans before being killed themselves. The airfield was now permanently in Allied hands.

Urbana Force had even tougher fighting on its front. A ravine called the “Triangle” was especially well defended by the enemy, and no progress could be made without reducing these fortifications. By December 27 the Americans enveloped the Triangle and the Japanese were forced to pull back. The next strongpoint was a field of kunai grass called “Government Garden.” The overgrown area was a perfect killing field for snipers, and the fighting also took its ghastly toll of human life.

After Christmas, fresh troops were brought in to relieve the exhausted and decimated 32nd. Help came from regiments of the American 41st Division as well as newly arrived Australian units. What was left of the shattered 126th Regiment came out of the line looking like so many emaciated skeletons.

Last Japanese Stronghold Confronts Allies

On New Year’s Day, 1943, Urbana Force linked up with Warren Force at Buna Station. The night before, enemy soldiers had been seen fleeing by boat or swimming toward the west beyond Gona where Japanese forces had gathered but were prevented from joining the battle by the Australians and swampy terrain. Those who escaped were in worse shape than the pathetic survivors of the 126th. All of them were sent back to Japan for the remainder of the war, unfit for further fighting.

By the evening of January 2, organized resistance at Buna was over. A few prisoners were taken, but these were mostly Chinese and Korean conscripts. There remained one last Japanese stronghold. Halfway between Gona and Buna was a nasty piece of jungle and swamp called Sanananda.

The Australians wanted the honor of taking Sanananda. They brought three tanks in to support their infantry before rains closed the roads. In the first assault all three tanks were quickly knocked out, and the accompanying infantry were picked off by snipers. The Australians lost a hundred men. The Japanese were not licked yet.

MacArthur Wins Battle With Marines

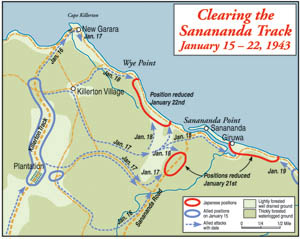

The final push began on January 15, when it was discovered that the Japanese had abandoned a strong position. Australians waded shoulder-deep through the swamps to flank remaining enemy positions. Meanwhile, each night the Japanese were evacuating their wounded on a fleet of barges. The Imperial Navy was no longer on the scene, but a small number of boats made their way down the coast by night, hiding in coves and inlets by day, until at last they were able to reach Sanananda.

The last pockets of resistance were overcome on January 22. The few sick and starving Japanese still surviving had to be hunted down and killed because they would not give up. MacArthur had won his battle with the Marines, who would not declare victory on Guadalcanal until February 9.

“A Magnificent Tragedy”

The casualties on both sides had been staggering, the Allies suffering 6,419 killed, wounded, or missing at Buna. Comparatively, on Guadalcanal the Americans suffered 5,845 total casualties. The Japanese at Buna/Gona lost 8,546, nearly all of them dead. Senior commanders in the Japanese Army later referred to the New Guinea campaign as “a magnificent tragedy.”

Both the Americans and the Australians were exhausted from their victory. There would be no new offensive operations on New Guinea for six months. When fighting began again, pockets of Japanese along the north shore would be bypassed altogether and left to starve in the jungle. The Allied strategy of “Island Hopping” grew in part out of fear of another Buna.

Subsequent battles of World War II would take higher death tolls on both sides, but never again would Allied armies go into battle as unprepared as they were at Buna.

My dad fought in the Battle of Buna, AJ Fitts. He was interviewed by an Australian newspaper. All he said was, it was really bad. And that was basically all he told me. He told me a few other things. He caught malaria and got sent home. Thank you.

My father in law, Paul Johnson from JAckson Mi fought at Buna with the 128th of the 32nd division. He stayed with the division all the way to Yamashita’s surrender in Phillipines. He would never talk about Buna either. We took him back to Australia to visit the old training camps and R and R places. We visited the sons and dtrs of families of friends he had made there. A real hero!