By Eric Niderost

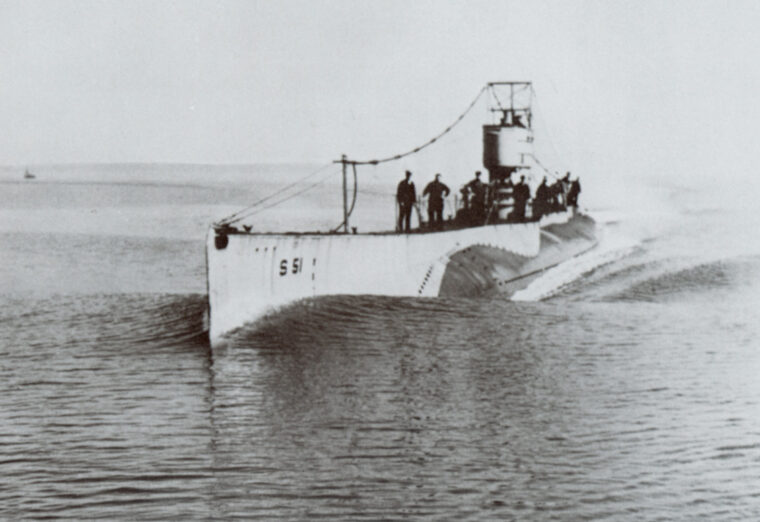

On September 14, 1938, fleet submarine USS Squalus (SS-192) was launched at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine. The occasion was filled with pomp and ceremony long established by Navy tradition. A bottle of champagne christened the 310-foot-long vessel, and as she slid down the ways the spine-tingling strains of “Anchors Aweigh” filled the ears of the crowds that had assembled to watch.

Final Fittings For Sisters Of the Sea

The Squalus was now in her natural element, though the waters of the Piscataqua River were still a far cry from the ocean depths. It was a good beginning, but there was a lot yet to be done on the fledgling boat. Straining tugboats towed Squalus to a fitting-out pier where diesel engines, electric motors, and other critical components would be duly installed.

The USS Sculpin (SS-191) was undergoing a similar fitting out at a nearby dock. Sculpin, launched only three months earlier, was identical to Squalus. As only one of two submarines launched in Kittery that year, Sculpin could claim kinship in both design and place of birth. Normally such boats would go their separate ways, but in this case fate decided otherwise. Over the next four years, Squalus and Sculpin and their crews would be drawn together in a common, irony-tinged destiny.

Bracing For War’s Outbreak

The United States was at peace, but the world was in turmoil. The Japanese were engaged in a bloody war of conquest in China, and that same September Hitler’s demands for the Sudetenland sparked the Munich crisis. Most Americans were isolationists, taking naïve comfort in the broad oceans that distanced them both physically and emotionally from the woes of the rest of the world. With half the globe teetering on the precipice, submarines like Squalus and Sculpin would be urgently needed.

Once they were internally complete, the two boats were commissioned, the Sculpin on January 16, 1939, and the Squalus on March 1, 1939. Both would then have to undergo a series of vigorous sea trials before being assigned to regular duty. Sculpin, having been launched earlier, completed her trials first and was duly certified to join the Pacific Fleet.

Grueling First Test For Newly-Christened Squalus

On Tuesday, May 23, 1939, USS Squalus went out to sea for a particularly crucial practice dive. Her skipper, Lieutenant Oliver Naquin, wanted to perform an emergency battle descent. The submarine had to dive to periscope depth—50 feet—in 60 seconds while running at 16 knots. It could be a tall order for a new boat, but in the last trial run Squalus had missed the mark by a mere five seconds. The sun had disappeared behind the clouds, but the skipper’s mood did not match the lowering weather. Naquin was confident Squalus could reach the goal.

The Squalus had performed well in 18 practice dives; all that was needed was a little fine- tuning. There were 59 men aboard—51 enlisted men, five officers, and three civilian inspectors—and morale was high. The Squalus nosed into the broad Atlantic, eventually reaching a point about five miles off the Isles of Shoals. It was an area still over the continental shelf, with an average depth of about 250 feet.

”Stand By To Dive!”

Once they reached the spot designated for the test dive, Naquin ordered the radioman to send their position back to shore. The radioman, Charles Powell, complied but gave the location as longitude 70˚31´ rather than 70˚ 36´. This was a difference of five miles, in light of subsequent events an almost fatal error. After the boat was rigged for diving, Naquin ordered, “All ahead, emergency!” The skipper was pushing Squalus to the limit, gaining momentum for the final plunge. After ordering “Stand by to dive!” Naquin left the bridge, then climbed down into the conning tower, making sure the hatch was closed against the soon-to-be rising waters. It was 8:30 on the morning of May 23, in Navy parlance, 0830 hours.

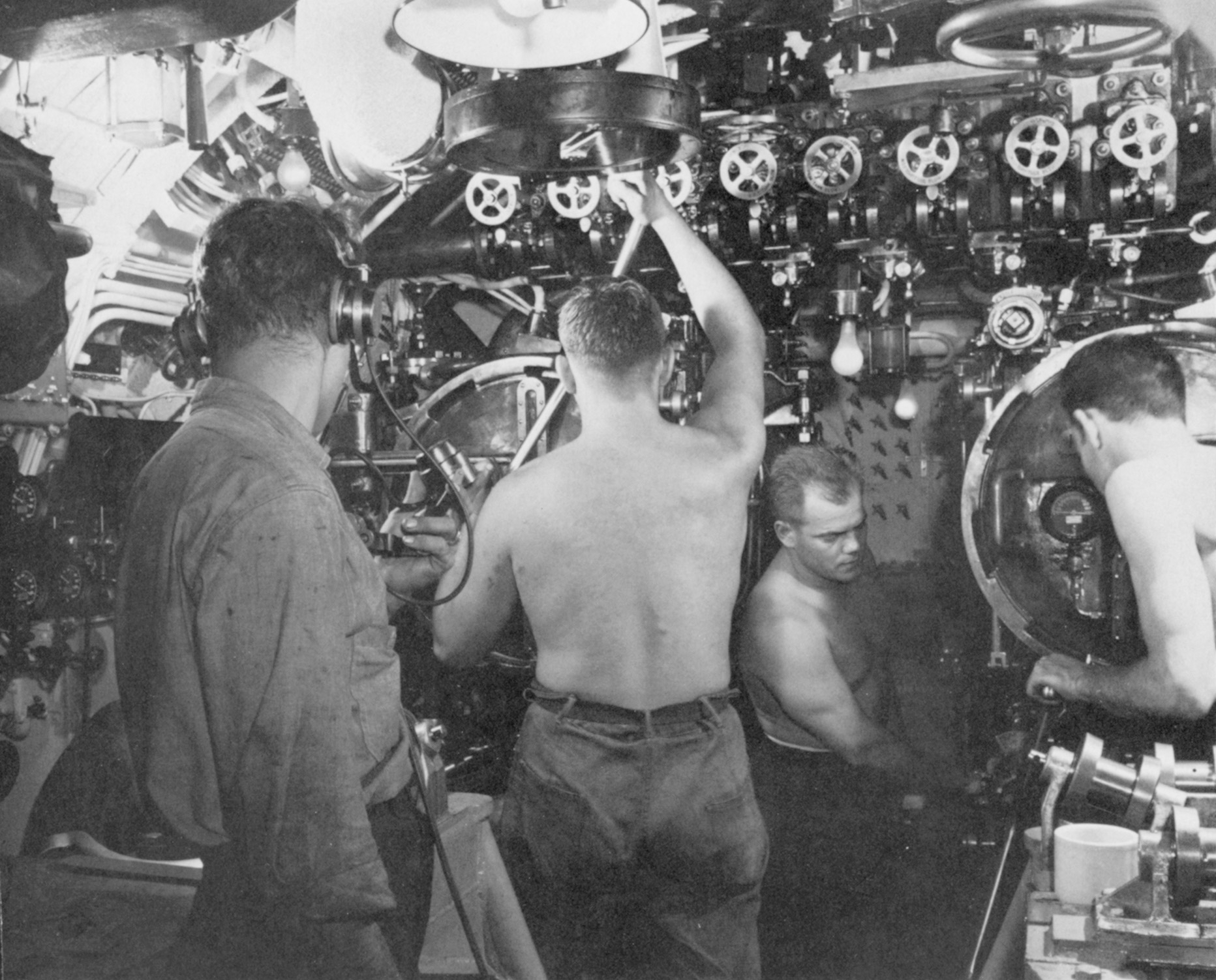

The klaxon diving alarm sounded, its raucous “ah-oo-ga” sounding like the horn of a Ford Model T. Naquin descended to the control room, the nerve center of the boat. There were 10 men there, including Squalus’s executive officer Lieutenant Walter Doyle and Harold Preble, a civilian naval architect there to observe the proceedings. The boat’s pressure hull—the steel tube where the crew lived and worked—was cocooned by ballast tanks. It was these ballast tanks that gave a submarine its exterior “pregnant” appearance. When these ballast tanks were flooded, the weight of the water pulled the submarine down into the depths.

Dual Propulsion System Was a Technical Marvel

Submarines of the 1930s and 1940s had a dual propulsion system. On the surface, four diesel engines supplied the power that indirectly turned the propellers. When Squalus submerged, the diesels would be shut down, replaced by two 126 lead acid-cell batteries. The diesels required a large intake of air while operating, which was supplied by twin pipes known as the main inductions. The main inductions joined a larger pipe that poked its way through the superstructure to the surface. A smaller steel tube nearby was connected to a latticework of air pipes that supplied ventilation to the boat when she ran on the surface. When a submarine dived, a steel plate known as a high induction valve hydraulically slid over the pipes to prevent seawater from flooding the vessel.

Perhaps the most important piece of equipment during a dive was the control board, called the “Christmas tree” because of its bank of lights. This panel indicated when all hull openings were sealed against the sea. If a light was red, the hull opening was open; if green, it was closed.

All Lights Green

At first all went like clockwork. The diesels were shut down, their ear-splitting throb reduced to an eerie silence within moments, and the transition from engine power to batteries was soon accomplished without a hitch. Lieutenant Doyle kept his eyes glued to the control panel as the row of lights changed from red to green. The light for the diesel exhaust valves turned green, as did the flapper valve for the radio antenna. On and on it went, until the last two lights—indicating the all-important induction air vents—changed color. All lights were green, the emerald glow reassuring Doyle that the hull was safe against the sea.

Squalus slipped under, and for all its bulk the boat dove with the ease and grace of a dolphin. When the sub reached 50 feet, the skipper looked at his stopwatch. It was just a tiny fraction over 60 seconds, causing Naquin to break into a broad grin. Preble, also checking his watch, confirmed the findings and added, “Good, good!” In each compartment of the boat there was a “battle talker,” a man with a microphone and earphones who could instantly relay information to the control room. So far, everything was proceeding normally.

“Engine Room’s Flooding Sir!”

There was a kind of pressure surge, which Naquin could feel gently pressing against his eardrums. “Engine room’s flooding sir!” control room talker Charles Kuney suddenly cried, his face a mask of shock and disbelief. Lieutenant Doyle grabbed Kuney’s headset just in time to hear an anguished “Take ‘er up! The inductions are open!” crackle through the earphone. That meant the high induction valve was not closed, and the twin induction tubes were spewing water into the engine room with the force of a broken water main.

Naquin knew the next few seconds would be crucial. “Blow the main ballast,” he shouted, following the command with “Blow safety tanks!” and “Blow bow buoyancy!” Compressed air would be shot into the ballast tanks, forcing water out and making the sub rise to the surface. The Squalus rose by the bow, even momentarily breaking the surface, but the boat could not overcome the tons of seawater that were pulling it down.

Chief Electrician’s Mate Lawrence Gainor looked into the forward battery, where a sight both hypnotic and deadly greeted his eyes. Miniature electric bolts were dancing from battery to battery, blue-white arcs that melted insulation with 70,000 amps of pulsating power. Steam was pouring off the batteries, a sure sign that the cells were shorting and an explosion was a heartbeat away. Risking death, Gainor reached for the disconnect switches and managed to cut power. The boat was plunged into darkness and continued its descent into the abyss.

Sqaulus Sinks To Ocean Floor

Seawater was now flooding the network of ventilation pipes that ran though the Squalus and served as the boat’s lungs. Each pipe now shot tiny jets of water like a sieve, the crew desperately trying to close lines to stop the leaks. All watertight doors between compartments had been ordered closed. Naquin assigned Lloyd Maness to shut the 300-pound oval door that separated the control room from the flooding sections aft. Seven men from the flooding area managed to reach the safety of the control room in time, but then the door had to be closed against the rising waters. There was no other choice.

The Squalus finally hit bottom, landing on the muddy ocean floor 240 feet beneath the surface of the Atlantic. The boat had landed upright, the bow slightly tilted upward at an angle of about 11 degrees. The plunge had been traumatic, but the actual impact with the ocean floor had been surprisingly gentle. There was no power, and even the emergency lights winked out. There was also no heat, and the water temperature at this depth was just above freezing.

Twenty-Six Unaccounted For and Presumed Dead

The control room was still the nerve center of the crippled sub. Hand lanterns were broken out, their pallid beams stabbing through the frigid gloom. Captain Naquin took stock of the situation. Like every good commander, his first thought was for his men. He personally took the headphones and tried to reach the aft compartments, only to meet with a heartbreaking silence. One of the boat’s distress rockets was fired, breaking the surface to rise and explode 80 feet above the rolling sea.

Naquin told Lieutenant Nichols to release the marker buoy, a relatively new innovation for submarine recovery. The bright yellow buoy was soon bobbing amid Atlantic swells, tethered to a long trailing telephone line that linked it to the stricken sub. A message on the buoy read “Submarine Sunk Here. Telephone Inside” in large bold letters. Four officers, 28 enlisted men, and one civilian were alive, making 33 souls all told. That left 26 men unaccounted for and presumed drowned.

Skipper Takes Charge To Save His Crew

It was a chilling statistic, but Naquin’s main concern now was for the safety of the survivors. He calculated that they had enough air for about 48 hours, if movement and talking were kept to a minimum. There were 23 men jammed in the control room, so to relieve the congestion Naquin instructed five men, including the civilian Preble, to a forward compartment.

Seawater had collected in the forward battery, its presence raising new concerns. If the water ever found its way into the dry battery cells, a chemical reaction would result that would produce a deadly fog of chlorine gas. The pantry and officer’s quarters were located just above the batteries; Naquin instructed that the forward sections be stripped of blankets and food, then sealed off.

Now it was a matter of waiting for rescue, though as a last resort there was always the Momsen lungs. Momsen lungs, invented by Lieutenant Commander Charles “Swede” Momsen, were breathing devices that looked something like inflatable life vests. In this case the depth and the near freezing temperatures made the use of such devices problematic, and if the crew lost their grip on the line that ran to the surface, they risked ruptured lungs. No, the best thing to do was to await rescue, trusting to God and the professionalism of the U.S. Navy.

Sculpin Ordered Out To Assist Squalus

That same morning Lt. Cmdr. Warren Wilkin was making final preparations for the Sculpin to depart Portsmouth. Wilkin, whose nickname was “Wilkie,” was in fine spirits because his boat was going to join the Pacific Fleet. It was almost 11 am when Wilkin saw Admiral Cyrus Cole boarding the Sculpin at a brisk pace. A look of deep concern was written all over the Admiral’s face; this was not a social call. “Wilkie,” Cole explained, “I want you to shove off immediately. We’re not sure, but Squalus may be in trouble, big trouble…”

Wilkie was given the Squalus’s last radioed position, but no one knew that position was off by several miles. Sculpin would have come swiftly to the aid of any stricken vessel, but the fact that Squalus was in trouble gave the mission added poignancy. The two boats were sister ships, launched only a few months apart from the same ways. Their crews knew each other, bunked in the same building ashore, and had developed a sort of friendly rivalry. One sailor later recalled, “The Sculpin regularly beat Squalus in softball. And the Sculpin seemed to get all the girls.”

When Sculpin arrived at Squalus’s last known position there was nothing but open sea. Certainly, there were no signposts of disaster, such as floating debris or an oil slick. But in this case no news was definitely not good news. The search continued, and Lieutenant (j.g.) Ned Denby spotted the telltale whips of a distress rocket. The sighting was confirmed by Captain Wilkins just as the smoke evaporated into the sky. It was nearly 1 o’clock in the afternoon, and the Squalus’s crew had shivered in its icy tomb for over four hours.

“Hello Squalus…What’s Your Trouble?”

Sculpin located the marker buoy, pulled it aboard, and dropped anchor. Wilkin got on the phone and said, “Hello Squalus, this is Sculpin. What’s your trouble?” Squalus’s exec Lieutenant Nichols gave Wilkin a quick rundown, then asked Wilkin to hold the line while he got the captain. “Hello, Wilkin!” Naquin began, his voice tinged with obvious relief. “Hello, Oliver,” came the reply, but just at that moment an ocean swell snapped the phone cable and broke off communication.

The USS Falcon, a former minesweeper, was the designated rescue “Mother Ship” for the operation. Time was of the essence; Falcon was relatively slow, and it was some 200 miles from its New London, Conn., base to the accident site. The single most important piece of equipment aboard was a revolutionary new rescue diving bell.

A Risky Plan Devised

Formally styled the McCann Rescue Chamber after a later modifier, the bell was really the brainchild of “Swede” Momsen. It was a light gray steel cylinder 7 feet wide and 10 feet high, and weighing some 18,000 pounds. The chamber could be lowered down to a submarine’s escape hatch, where a watertight seal was made via a rubber gasket. It could hold as many as seven survivors at any one time.

A small flotilla assembled at the site, including the tugs Penacook and Wandank and a number of Coast Guard vessels. Once Admiral Cole arrived on the scene, he made the Sculpin his command post in the developing rescue effort. The admiral and Commander Momsen conferred aboard Sculpin, reviewing their options, which narrowed down to three. The first was to pump out the flooded sections of Squalus, which was risky. The trapped crew could use their Momsen lungs, but they were numb with cold and aching with fatigue. Besides, the lungs had only been tested for a maximum depth of 207 feet.

No, the best option was to use the diving bell. By the time Falcon arrived with the McCann Rescue Chamber the crew had been down for 21 hours. Time was running out, and much depended on the capacious whims of the Atlantic. If the weather held, and the seas remained calm, all would be well. But if not….

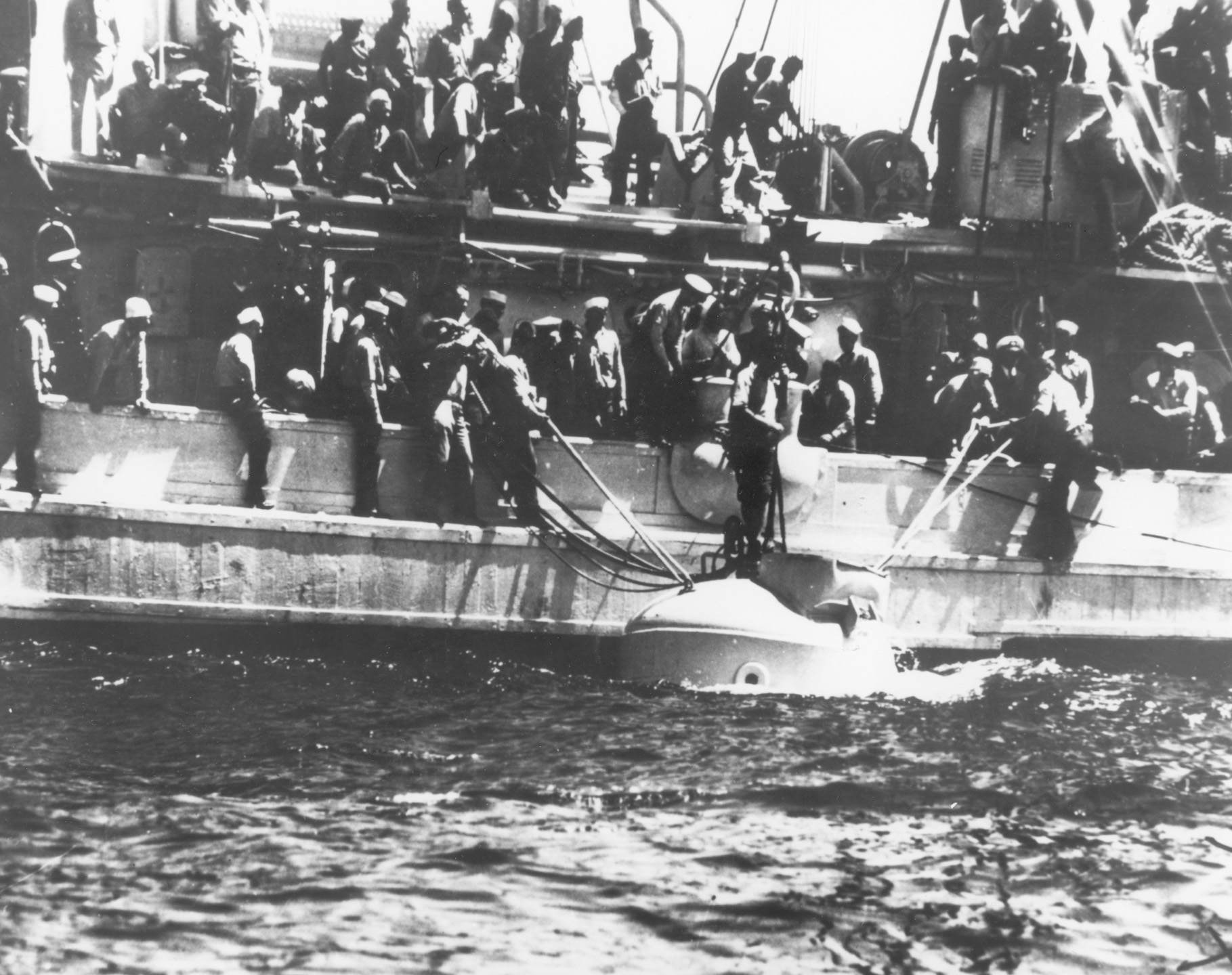

Diving Bell Proves Its Worth

The diving bell was deployed, and for the next six hours 25 survivors were brought to the surface in three trips. The fourth trip was really touch and go, since the bell developed some problems with tangled cables. After some heart-stopping moments, the bell successfully made it to the surface just after midnight on May 25. Among the last to be taken up was Captain Naquin, following a time-honored tradition.

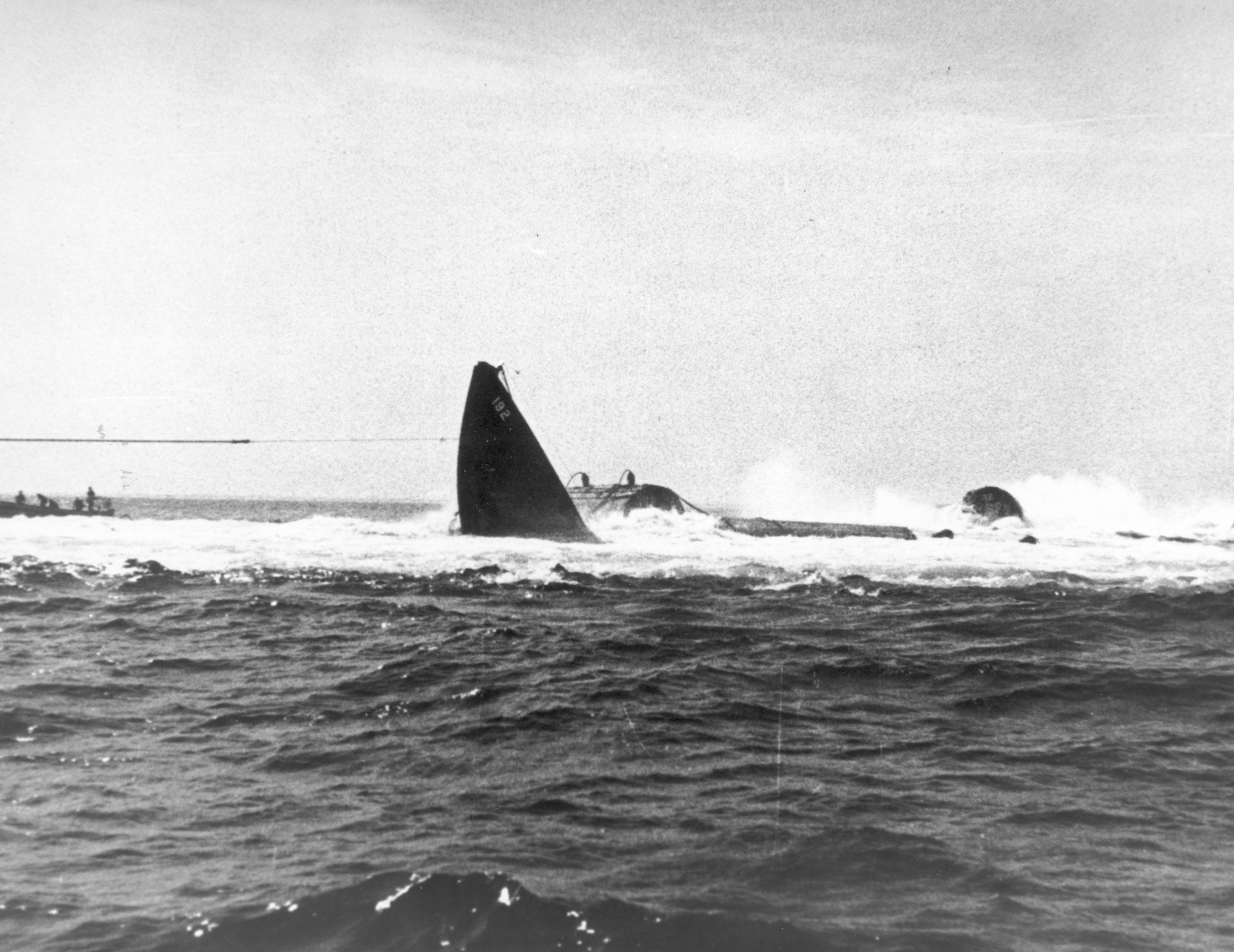

A decision was made to salvage the Squalus, a dangerous and time-consuming operation that lasted three months. Hampered by rough seas and bouts of nitrogen narcosis, courageous Navy divers passed cables underneath the hull and attached pontoons on either side. The operation was so risky the divers received the Medal of Honor for their Herculean efforts.

Sculpin also was on hand during the recovery operations. Finally, in the fall of 1939, Squalus was raised and towed back to Portsmouth Navy Yard. Repairs were made, and the boat was recommissioned in 1940 as the USS Sailfish. President Franklin Roosevelt personally suggested the new name. He was an avid sportsman, and when he saw a photograph of the Squalus re-emerging to the surface bow first it reminded him of a leaping Sailfish. With typical wry humor, many sailors took to calling the reincarnated craft “Squalfish.”

Sculpin and Renamed Squalus Depart For Pacific Duty

Her rescue and recovery chores successfully completed, Sculpin proceeded to the Philippines to join the Asiatic Fleet, Submarines. Sailfish joined her a few months later, arriving in early 1941. Both submarines were in the Philippines when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 (December 8 local Manila time). Sculpin and Sailfish made their first war patrols while in the Philippines; faulty torpedoes made these debuts decidedly inauspicious.

Sculpin and Sailfish managed to escape the fall of the Philippines, and in time their scores improved. From January 1942 to January 1943, Sculpin was based in Java and Australia and had sunk two enemy ships and damaged several others. Sailfish’s record would also dramatically improve with time, and by the end of the war the boat would win a Presidential Citation.

By 1943, the darkest days of the war were over, though there was still a lot of hard fighting to be done. Operation Galvanic, a major U.S. offensive in the Central Pacific, had the Gilbert Islands as its major objective. Makin, Abemama, and Tarawa—volcanic atolls that poked up from the blue Pacific like jagged teeth—were the three major islands in the Gilbert chain.

Subs Called On To Disrupt Japanese Relief Efforts

Submarines would play a vital support role in the operation, their primary task to prevent any Japanese naval forces from aiding beleaguered garrisons in the Gilberts. The Japanese suspected an offensive was imminent but did not know where the blow would fall. The main Japanese base in the Central Pacific was Truk, 1,400 miles southwest of the Gilberts, and it was logical to assume that any sorties would come from there. Truk and its immediate environs remained a primary focus for U.S. submarines.

In the fall of 1943, Vice Admiral Charles A. Lockwood summoned Commander John P. Cromwell to his Pearl Harbor office. Lockwood was COMSUBPAC, Commander Submarine Force Pacific Fleet, and already something of a legend among submariners. Taking his cue from German U-boats operating in the Atlantic, Lockwood wanted to take their “wolfpack” concept, give it an American twist, and apply it to the Pacific Theater. Wolfpacks were groups of submarines operating in concert, supporting each other in such a way as to dramatically increase the number of enemy vessels that were sent to the bottom.

Debut Of the American Wolfpack

German U-boats were directed from the land, a somewhat impractical method given the vastness of the Pacific. To solve this problem, Lockwood decided that immediate tactical control would be given to an on-scene squadron commander. This commander would be a passenger aboard one of the wolfpack subs. When a Japanese convoy was sighted, the squadron commander could alert the other subs in his wolfpack and help coordinate attacks.

The American wolfpack plan looked good on paper, but early trials were considered a failure. Undeterred, Lockwood decided to try again, and that is why he had summoned Cromwell to his office. He was going to be squadron commander of a wolfpack, and as Lockwood personally briefed the commander, he strongly emphasized the need for complete secrecy. COMSUBPAC had every confidence in his abilities; Cromwell was already party to Ultra, the Allied intelligence source derived from the decryption of enemy ciphers.

Cromwell’s headquarters would be the Sculpin, though immediate control of the boat would be vested in its new skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Fred Connaway. The Searaven (SS-196) and the Apogon (SS-308) would round out the rest of Cromwell’s wolfpack command. USS Spearfish might join the wolfpack if circumstances warranted it. Cromwell’s primary mission was to keep an eye on Truk, intercepting and sinking any enemy vessels trying to reach the Gilberts. He was also to use his wolfpack to locate a group of cruisers and carriers en route from Japan and send them to the bottom.

Sculpin Given Rousing Hawaiian Sendoff

When Sculpin left Pearl Harbor on November 5, 1943, it was given a rousing send-off in keeping with the finest traditions of the service. A band played “Aloha” and “Sink ’em All,” and Admiral Lockwood himself was at dockside. Sculpin was beginning her ninth war patrol, an ill-fated venture destined to be her last.

After stopping briefly at Johnson Atoll to refuel, Sculpin sailed another 3,500 miles to the waters off Truk. A Japanese ship was detected the night of November 18-19 heading north at 14 knots. Radar later determined the ship was not alone, but part of a convoy consisting of one freighter, five destroyers, and a cruiser. Commander Connaway decided on a classic “end run” that would put Sculpin in attack position by dawn. When all was ready the crew went to battle stations and the boat dove into the Pacific, disappearing into its own white-capped wake as waves collided over its teakwood decks.

A Close Call With a Japanese Convoy

Suddenly the convoy turned, heading for where the Sculpin was lying in wait. Had she been detected? “Down scope!” Connaway cried, following the terse command with an urgent, “Emergency 200 feet!” The sub slid down into the murky depths, the cushion of seawater its only protection against the depth charges that were bound to follow. But contrary to expectations, no depth charges were dropped. The Japanese convoy sailed on, actually passing over the hiding sub.

Cromwell and Connaway huddled, and both men agreed that the freighter was worth a second try. After all, it must be carrying something of vital importance. Why else would a single ship have such a powerful escort? After an hour of submergence, Connaway took Sculpin up to periscope depth for a look around. The coast seemed clear, so Sculpin surfaced at around 7:30 am, November 19. Quartermaster Billie Minor Cooper and Lieutenant John Allen went topside and swept the horizon with their binoculars. They caught sight of something in the far distance—a Japanese ship?

Hunter Becomes the Hunted

Considering it better to be safe than sorry, Connaway took the boat down once again. A quick look into the periscope told the tale: The Japanese destroyer Yamagumo was coming up fast. It was a “sleeper,” a destroyer that purposely detached itself from the convoy to drop back a few miles in hopes of catching an American submarine off guard. The ruse worked. Now the hunter was the hunted.

Sculpin dove to 300 feet, rigged for silent running, then braced itself for the inevitable. The Yamagumo did not disappoint, launching 17 600-pound depth charges in the initial run. The metal cylinders detonated in 30-second intervals, each underwater blast forming a bubble that radiated lethal percussion waves in all directions. Shock waves pummeled the Sculpin unmercifully, battering the vessel with a series of sledgehammer blows. The hull swayed with the impact, and as the boat shook small geysers of water erupted from numerous leaks. If not controlled, the small geysers could unite into a flood that would complete the destroyer’s deadly work.

Yamagumo’s sonar had a good fix on the Sculpin. The telltale “pings” that the sub crew could hear between attacks left little doubt about that. The first depth charge run was followed by a second, then a third. Sculpin was taking on water, but the pumps soon burned out and were useless. A rain squall on the surface caused the destroyer to break off the attack, but Connaway was forced to keep the sub down for a few more hours just to play it safe.

Mounting Pressure Would Soon Crush the Sub Like an Empty Tin Can

Though fate had granted Sculpin a temporary reprieve, the crew was too busy trying to seal leaks and bail collecting water to take much of a breather. After about nine hours the air was growing foul and the heat unbearable, with temperatures reaching upward of 115 degrees Fahrenheit. Instruments were broken and battered, and the all-important depth gauge was so damaged it was unreliable. Connaway ordered the boat to go to periscope depth.

But the boat rose too fast, its bow actually breaking the surface. “Take her deep!” cried the skipper. “All ahead full!” There was good reason for urgency—the Yamagumo was only 5,000 yards away. She plunged once again into the depths, but the sea was now more foe than friend. The Sculpin was so damaged she was out of trim and nearly uncontrollable. The crippled boat reached 700 feet, well below her theoretical crush depth. The hull plates groaned with the stress; soon the sub would be crushed into a heap of twisted metal like an empty tin can.

A Surface Battle Was Better Than a Watery Grave

Luckily, the crew gained control and the boat began to rise, but the batteries were almost drained of power. How much longer could she absorb punishment? How much longer could she stay beneath the surface? Connaway felt he had only one option—battle surface. Submarines have relatively thin hulls, at least in terms of shellfire, and are not designed to take on destroyers on their own terms. Still, Connaway felt a surface battle was better than a watery grave.

Captain Cromwell strongly disagreed with Connaway’s decision, though he would not pull rank to overrule him. The wolfpack commander argued that the destroyer must be low on depth charges, 57 had already been dropped. Maybe the Japanese were already out of them. It was six hours to nightfall—a long time but not impossible. The Japanese would have to break off the attack if they ran out of depth changes, and once night fell Sculpin could surface and escape.

No Match For the Yamagumo

Connaway disagreed, and his decision sealed the fate of the boat and all aboard her. Sculpin surfaced at 1:30 in the afternoon, the sailors scrambling on its water-slick deck to man the 3-inch deck gun and the 20mm batteries. Sculpin managed to fire two rounds at the Yamagumo, but there was little doubt as to who would win the unequal contest. The destroyer opened up with its 5-inch guns, the first salvo bracketing the sub in towering geysers of water. A shot scored a direct hit on the conning tower, killing Connaway and several other officers. It was followed in rapid succession by a 5-inch shell that pierced the forward torpedo room, killing several men in the process. Parts of the Sculpin were now a twisted wreck, the dead and wounded in bloody heaps.

Lieutenant George Brown now found himself in command of the stricken boat. There was nothing left to do but scuttle the vessel and order abandon ship. Cromwell concurred, but told Brown he was staying aboard. Cromwell explained he knew too much to risk capture. He would be a valuable prize if he fell into Japanese hands, and there was always the possibility, even the probability, the Japanese would use torture to extract information. Cromwell went down with the boat, calmly gazing at his wife’s picture as torrents of water swirled into the compartment. His act of selfless courage would win him a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Death Preferred To Japanese Captivity

About a dozen other men chose to “ride the boat down” rather than surrender. Such life-and-death decisions were intensely personal, but for the most part they preferred death to Japanese captivity. Tales of Japanese cruelty were legion, and certainly well-founded. Altogether 42 men were fished from the sea, three officers and 38 enlisted men. Japanese “rescuers” callously threw one badly wounded sailor overboard. It was a foretaste of things to come.

The Sculpin survivors, now POWs, faced their own harrowing ordeal. The Japanese treated the men with obscene brutality, denying them water and even basic medical treatment. They were taken to Truk, where they endured ceaseless interrogations and ill treatment. There was a bitter irony in the loss of Sculpin, because Cromwell had been right. The Yamagumo had only three depth charges left in its rack.

When the Japanese were finally convinced the Sculpin crew had nothing to tell them, it was decided they would be shipped to Japan. The surviving crewmen were divided into two groups; one party was placed aboard the escort carrier Chuyo, the other aboard the carrier Unyo. Besides these two vessels, the convoy included the large carrier Zuiho, the cruiser Maya, and two destroyers. Their ultimate destination was Yokohama, 2,000 miles away.

A Final Fatal Encounter For Sculpin and Squalus Crews

Over the past four years, the fates of sister ships Sculpin and Squalus/Sailfish had been bound together. Now, for a final time, destiny would link the two ships and their respective crews. On the night of December 3, 1943, the Japanese convoy bearing the Sculpin prisoners back to Japan and captivity encountered a severe typhoon. Howling winds whipped the sea into towering waves, and as conditions deteriorated the Japanese ceased evasive maneuvers. After all, what submarine would attack under such extreme conditions?

Such assumptions were logical, but sometimes war defies logic. Thanks to Ultra, the Americans were well aware of the Japanese convoy, and a trio of carriers was too tempting a target to resist. The Sailfish was in the area, and despite mountainous seas soon had Chuyo in its sights. Two torpedoes were launched, the “fish” scoring hits that soon had the ship ablaze. The mortally wounded carrier lingered for a while, but eventually succumbed and sank beneath the storm-lashed waves.

Sculpin Survivors Struggle In Captivity While Sailfish Fights On

The Sailfish had sunk a Japanese carrier, but not without a tragic cost. It was not known until after the war, but 20 of Sculpin’s surviving crewmembers perished with the Chuyo. George Rocek was the only man to survive the sinking. Picked up by a Japanese ship, he was taken back to Japan and eventually joined the survivors who had shipped out aboard Unyo. Confined at Ashio, the prisoners, mostly captured American submariners, were put to work at hard labor in a copper mine.

The Sculpin survivors had to endure the all-too-typical horrors of Japanese captivity. Sickness, hunger, and constant beatings were a daily occurrence. While the Sculpin crew and their fellow submariners struggled to survive, Sailfish continued to successfully sink Japanese ships.

On July 8, 1844, Sailfish received the coveted Presidential Unit Citation for an outstanding record. The award was ironic in retrospect, because Sailfish was particularly commended for the sinking of the Chuyo, “the first known unassisted sinking of an enemy carrier by a submarine of this force.”

Memorial At War’s End To America’s Silent Service

From May 1943 to December 1944, Sailfish conducted a further five patrols. In January 1945, she was transferred to the Atlantic, where she was used as a training vessel for the rest of the war. The prisoners at Ashio knew the war was over when they saw their guards with tears streaming down their faces. They found out later that Emperor Hirohito had just given a radio address, saying that Japan had to “endure the unendurable” and surrender. Official release came on September 5, 1945. By some miracle, all 21 of Sculpin’s remaining survivors lived to see the end of the war.

The USS Sailfish was decommissioned after the war and scrapped in 1946. The bridge, conning tower, and a piece of the deck were preserved as a memorial. The Sailfish/Squalus memorial honors her war record and her remarkable survival. But in a very real sense it also honors its sister ship Sculpin and all other vessels of America’s silent service.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments