By Christopher Miskimon

The Six-Day War began on June 5, 1967, with a lightning assault by Israeli armored units and aircraft. The Egyptian Air Force, caught at their airfields, lost 304 planes the first day, granting Israel’s pilots free reign over the battlefield. Below them, long columns of tanks and armored personnel carriers struck Egypt’s ground forces with equal ferocity across the dusty sands of the Sinai. The Egyptian troops were entrenched. “Massive troop concentrations and strongly fortified positions, some of which had been prepared over the last 20 years,” wrote Israeli Maj. Gen. Israel Tal. Both armies were well-equipped with armored vehicles of every description.

Most of the Egyptian’s 950 tanks in the Sinai came from their Soviet benefactors. Their armored and mechanized divisions used the T-54/55, a low-slung vehicle with a rounded turret and a 100mm gun. These outfits also had a few PT-76 light amphibious tanks, often used for reconnaissance. The older, World War II-era T-34/85 equipped the Egyptian infantry divisions, furnishing fire support. A handful of heavy Joseph Stalin tanks rounded out their numbers.

The Israeli tank force possessed a more diverse inventory, as they had been forced to acquire their armor from a variety of sources. The armored units used a mix of British-built Centurions and American M48 Pattons as their main battle tanks. Three battalions of the Israeli Army used the light AMX-13, a French design. Mechanized brigades had a battalion of upgraded Sherman tanks to accompany their two battalions of half-track borne infantry. Interestingly, the Egyptians had a Palestinian Division in the Sinai that also had 50 Shermans in support.

As Israeli artillery dropped thousands of rounds on the Egyptian positions, the tankers attacked. “The Centurions met the first ‘danger’ or defense fire from one of the outposts, and we moved to a higher position from which we could see our forces moving,” recalled Lieutenant Yael Dayan, who served in Maj. Gen. Ariel Sharon’s division, which attacked Egyptian forces at Abu Agheila. “For a while I felt as though I were watching a game. Tanks dispersed in the area, shells heard and seen, the wireless set like a background running commentary—there was something unreal about it all.”

The Centurions became stuck in a minefield as artillery pummeled them. A unit of Shermans made a feint, drawing Egyptian fire to help the Israeli artillery observers. This enabled six Centurions to get into the Egyptian position, where they quickly knocked out 5 T-34/85s and put 15 more to flight. Soon the Egyptian retreat became more general. “Enemy tanks were roaming on the road, along the road, on the sides, in opposite directions,” Dayan wrote in his diary. “About 20 of them were destroyed, one-point blank from ten yards, after he was trodding along for five miles in our own column either pretending he was Israeli or not knowing he wasn’t amongst his own Egyptian tanks.” A second line of Egyptian defenses soon fell to the Israelis. Although the Israelis lost 19 tanks, they destroyed 60 Egyptian tanks.

The Centurions became stuck in a minefield as artillery pummeled them. A unit of Shermans made a feint, drawing Egyptian fire to help the Israeli artillery observers. This enabled six Centurions to get into the Egyptian position, where they quickly knocked out 5 T-34/85s and put 15 more to flight. Soon the Egyptian retreat became more general. “Enemy tanks were roaming on the road, along the road, on the sides, in opposite directions,” Dayan wrote in his diary. “About 20 of them were destroyed, one-point blank from ten yards, after he was trodding along for five miles in our own column either pretending he was Israeli or not knowing he wasn’t amongst his own Egyptian tanks.” A second line of Egyptian defenses soon fell to the Israelis. Although the Israelis lost 19 tanks, they destroyed 60 Egyptian tanks.

The rest of the fighting in the Six-Day War was often just as one-sided. The fighting here proved emblematic of armored warfare across the globe during the various hot conflicts of the Cold War. The United States and its NATO allies were faced off against the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact, but both sides were unwilling to risk the chance of nuclear escalation from a direct confrontation. Instead, the two sides fought proxy wars, equipping their clients with their own weapons. This was a theme repeated time and again during the last half of the 20th Century. This theme is also expertly recounted in Tank Battles of the Cold War 1948–1991 (Anthony Tucker-Jones, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire UK, 2021, 233 pp., photographs, appendices, bibliography, index, $43.95, hardcover).

The author does an excellent job summarizing the various conflicts using large numbers of armored vehicles, starting with the Israeli War of Independence through to the battles fought during the breakup of Yugoslavia. The chapters on conflicts lesser-known in the west, such as the Ethiopian Civil War (1974-1991), the Indo-Pakistan War (1971), and the Chadian-Libyan War (1978-1987), are particularly informative, for the author has compiled the details of tank battles of which few in the English-speaking world are aware.

The book has good photo inserts, and a set of appendices provides detailed information on the Soviet bloc and Chinese tanks, which often formed the bulk of armor used in many of the wars of the period. The book also includes a chapter on how the Soviets liberally delivered their tanks to various nation states, several times reconstituting a country’s entire tank force. Readers interested in modern tank warfare will find this book of great interest.

Firepower: How Weapons Shaped Warfare (Paul Lockhart, Basic Books, New York NY, 2021, 608 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover)

Firepower: How Weapons Shaped Warfare (Paul Lockhart, Basic Books, New York NY, 2021, 608 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover)

Large blocks of Swiss mercenary pikemen fighting for the French crown advanced steadily on the morning of April 27, 1522, near Bicocca manor four miles north of Milan. The pikemen had not been paid recently, nor had they found any opportunity for plunder as a battle loomed with Spanish-Imperial-Papal forces commanded by Prospero Colonna.

Viscount de Lautrec, the French commander of the Swiss mercenaries, reluctantly consented to the attack. He ordered an artillery bombardment to soften the Spanish lines in preparation for the assault by the Swiss pikemen, but the Swiss felt no need for the preliminary bombardment. Shouldering their 18-foot-long shafts, they brushed past the artillerymen and advanced for the kill in a frontal attack on the enemy position.

Colonna had prepared his position well. He placed his cannon, arquebusiers, and landsknechts behind ramparts. He had lavishly equipped many of his troops with the newly introduced arquebus, believing that the gunpowder weapon would mow down the vaunted Swiss pikemen.

His Spanish-Imperial arquebusiers opened fire downing one out of eight Swiss pikemen as they closed the distance, but the pikemen came on, soon crowding into a sunken road. From their ramparts, Colonna’s arquebusiers, who were arrayed three ranks deep, fired punishing volleys into their foes, after which German Landsknechts, armed with two-handed swords, waded into the disordered Swiss ranks inflicting additional casualties.

When the fighting ended, 3,000 slain Swiss pikemen littered the field. The rest of the well-disciplined pikemen withdrew in good order. The French departed the next day, conceding control of Milan to the Spanish-Imperial-Papal army.

The relationship between technology and the evolving nature of warfare is the subject of this new book. Scientific advancement allowed new, ever-more effective and deadly weapons to enter the battlefield, changing the way soldiers fought and even how societies prepared for war. The author reveals the many ways technology pushed these changes, from the advent of gunpowder weapons to ironclad warships, explosives, automatic weapons, and submarines, to name a few subjects. The narrative is quite readable, and the book is professionally researched. While its overall scope is broad, each topic is given detailed coverage.

The Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club: Naval Aviation in the Vietnam War (Thomas McKelvey Cleaver, Osprey Publishing, Oxford UK, 2021, 400 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, glossary, index, $30.00, hardcover)

The Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club: Naval Aviation in the Vietnam War (Thomas McKelvey Cleaver, Osprey Publishing, Oxford UK, 2021, 400 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, glossary, index, $30.00, hardcover)

At 2:40 p.m. on August 2, 1964, the USS Maddox (DD-731) broadcast a flash radio message reporting several North Vietnamese craft approaching at high speed with the intention to launch torpedo attacks. Maddox would fire in self-defense if necessary. A further message went out requesting air support, and the USS Ticonderoga, steaming 280 miles south, sent a flight of four F-8E Crusader fighters, led by Commander James B. Stockdale, while the destroyer USS Turner Joy received orders to render assistance.

As the North Vietnamese boats approached, Maddox fired three warning shots. Minutes later, the ship’s guns let loose again, as the boats maneuvered closer, making ineffective attacks. The F-8Es arrived and strafed the boats, damaging all three and leaving one adrift. Maddox suffered a single hit from a machine gun round. The two mobile craft retreated; the third managed to restart its engines and limped home. America’s air war over Vietnam had begun.

What really happened that day has been the subject of speculation ever since and will likely never be answered to everyone’s satisfaction, but the author was a young sailor when his event occurred. He investigated it thoroughly and made it part of his latest book on military aviation. The work uses interviews from pilots on both sides as well as official records, weaving it all together into a good narrative of the naval aviator’s experiences in the war, as well as those of their opponents.

Military Reconnaissance: The Eyes and Ears of the Army (Alexander Stilwell, Casemate Books, Havertown PA, 2021, 173 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover)

Military Reconnaissance: The Eyes and Ears of the Army (Alexander Stilwell, Casemate Books, Havertown PA, 2021, 173 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover)

Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry ordered a reconnaissance in force on June 22, 1876, along the Rosebud River. He gave some leeway for Lt. Col. George Custer, the officer leading the mission, to use his initiative. Custer had several experienced scouts, both white and Native American, in his force. They soon found signs of substantial Native American villages and camps, along with evidence of large pony herds, indicating thousands of Indians in the area. Custer claimed he did not see the signs, and after learning opposing scouts had seen his column’s trail made ready to attack. The scouts pleaded with Custer to reconsider. they knew he was badly outnumbered. He refused, divided his command into three smaller columns, and rode to his death soon after.

This is an example of both the need to conduct reconnaissance and the danger of ignoring what it reveals. This new book is full of such examples, along with information about famous scouts and reconnaissance units. Scouting is a vital part of military operations and the authors does an excellent job providing case studies both at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels. The author’s own service in the British Army adds the authenticity of first-hand experience to the narrative.

Hold at All Hazards: Bigelow’s Battery at Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 (David H. Jones, Casemate Books, Havertown PA, 2021, 262 pp., $22.95, softcover)

Hold at All Hazards: Bigelow’s Battery at Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 (David H. Jones, Casemate Books, Havertown PA, 2021, 262 pp., $22.95, softcover)

Captain John Bigelow has just taken command of the 9th Massachusetts Battery of Light Artillery in early 1863. The unit, which was equipped with six 12-pounder Napoleon smoothbore cannon, had so far spent the entire war as part of Washington’s defenses. Training and discipline were poor, and Bigelow set out to correct those shortcomings. He made considerable headway instilling discipline. Bigelow’s battery was assigned to Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery’s 1st Volunteer Brigade of the Artillery Reserve of the Army of the Potomac in summer 1863.

The battery arrived at Gettysburg on July 2 when two divisions of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s I Corps reinforced by one division of the Confederate III Corps attacked the Union left flank arrayed behind Emmitsburg Road. As the Confederates overwhelmed Maj. Gen. Dan Sickles’ Union III Corps, Maj. Gen. George Meade dispatched batteries from his Artillery Reserve to help stabilize the crumbling Union line.

Ordered into the line with victory hanging in the balance, the artillerymen of Bigelow’s Battery were told they must hold at all hazards against the enemy, until a second gun line could be set up behind them. They fought like veterans, determined to play a significant role in helping stave off defeat.

This engaging new book is a work of fiction, but it draws from actual events, and its characters were actual people who served in the 9th Massachusetts Battery. The author used all the historical information he could gather to create a vivid and authentic portrayal of the Battery in action. The result is a novel that reads almost like a history, placing the reader on the battlefield amidst the smoke, shouted orders, and screams of the wounded and dying.

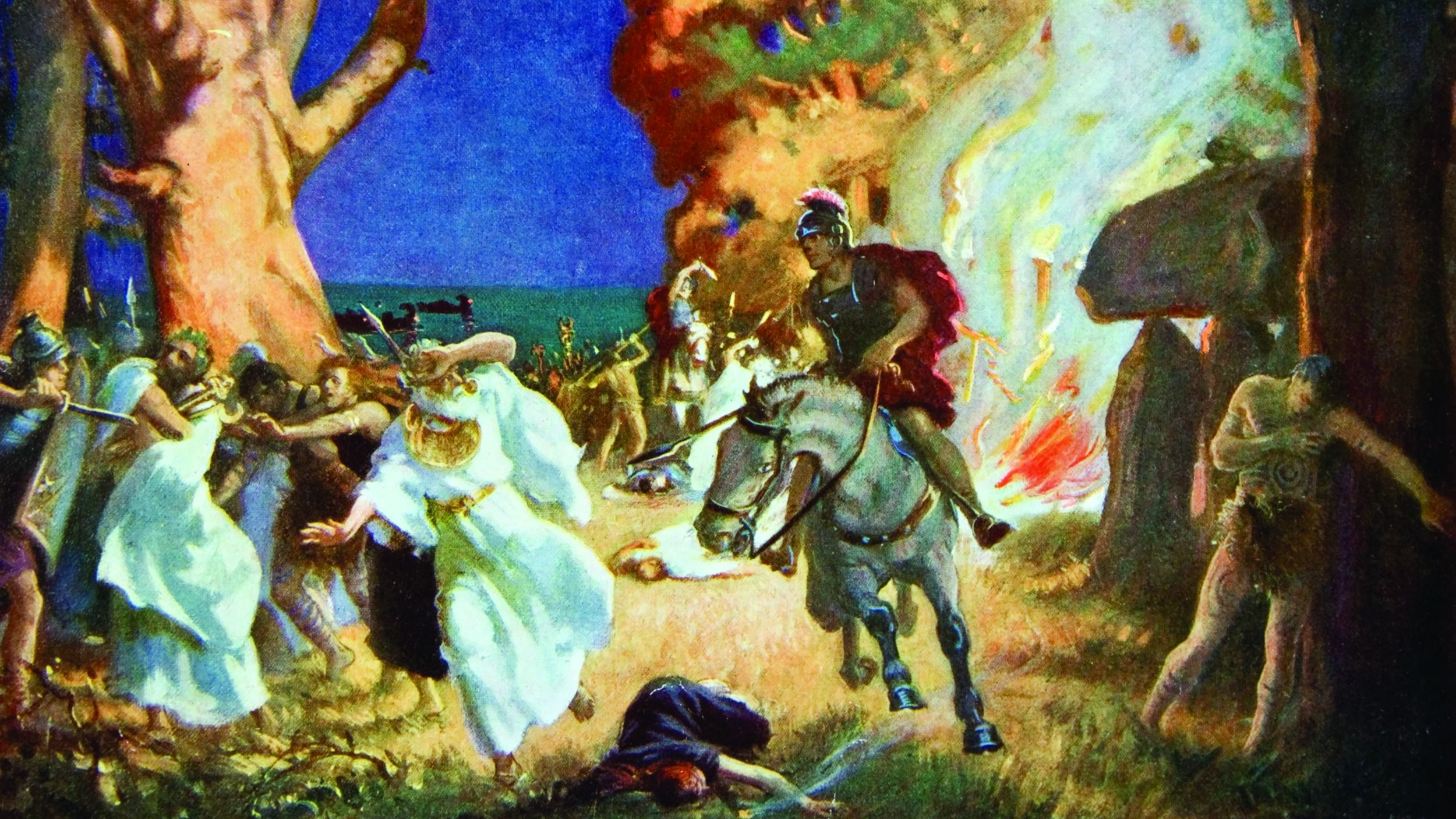

Legion Versus Phalanx: The Epic Struggle for Infantry Supremacy in the Ancient World (Myke Cole, Osprey Books, Oxford UK, 2020, 288 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, glossary, $20.00, softcover)

Legion Versus Phalanx: The Epic Struggle for Infantry Supremacy in the Ancient World (Myke Cole, Osprey Books, Oxford UK, 2020, 288 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, glossary, $20.00, softcover)

The Greek Phalanx dominated ancient battlefields for centuries until the Battle of Beneventum in 275 B.C. A deep box formation with tightly packed hoplites with large shields and long spears, the phalanx could be unwieldy but proved difficult to overcome. As warfare continued to evolve, the Roman legion was introduced. The principal weapons of the Roman soldier were javelins and short swords. At first the Roman soldiers also found the phalanx difficult to penetrate. However, the Romans learned from their failures. They adapted and innovated. The Roman legion undoubtedly was a more flexible military organization than the phalanx, but was that really the key to its success on the battlefield, with the Roman legion assuming supremacy for the next six centuries?

The author delves into the transition of dominance between these two famous fighting formations. The writing is lively and engaging, and there is also plenty of interesting information on the weapons, tactics and organization used by both sides. A number of battle studies show how Greeks and Romans fought in practice, putting the author’s hypotheses and assertions to the test of historical actions and outcomes.

The English Civil War: An Atlas and Concise History of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1639-51 (Nick Lipscombe, Osprey Books, Oxford UK, 2021, 367 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, glossary, notes, bibliography, index, $70.00, hardcover)

The English Civil War: An Atlas and Concise History of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1639-51 (Nick Lipscombe, Osprey Books, Oxford UK, 2021, 367 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, glossary, notes, bibliography, index, $70.00, hardcover)

The Battle of Newburn Ford fought on August 28, 1640, ended as a victory for the Scottish Covenanters over the English. The Scottish leader Alexander Leslie, with 20,000 infantry 2,000 cavalry and 60 guns defeated a much smaller English army under Lord Conway, which fielded 3,000 infantry, 1,500 cavalry and a single eight-gun battery. The Scots drove inexperienced British troops back across the ford and then crossed it. A British counterattack using cavalry failed, and soon the entire English force was in retreat. Lt. Col. George Monck, the English artillery commander, prevented an even worse disaster through the skillful handling of his guns, which kept the Scots at bay long enough for Conway’s forces to fall back. This brought to a conclusion one of the first engagements of the English Civil War, a series of conflicts between rivals in the United Kingdom.

The English Civil War can be difficult to understand and follow, particularly for readers who are not citizens of the United Kingdom. The author admits as much in the first paragraph of the introduction of this book. He then sets out to make the opaqueness of this conflict clear and succeeds in doing so. This large coffee-table book is well-organized with a clear narrative. The maps are excellent, detailed, and simple to follow. An extensive set of appendices informs the reader on the myriad small details of each army’s strength and compositions.

Into the Valley of Death: The Light Cavalry at Balaclava (Nick Thomas, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire UK, 2021, 357 pp., photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $42.95, hardcover)

Into the Valley of Death: The Light Cavalry at Balaclava (Nick Thomas, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire UK, 2021, 357 pp., photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $42.95, hardcover)

On October 25, 1854, in a valley in the Crimea near the besieged city of Sevastopol, 673 British cavalrymen charged Russian artillery positions against terrible odds. They paid a heavy price for their obedience to orders, suffering devastating casualties from the storm of cannon shot and musket balls that assailed them as they rode. Their leaders spurred them to go as fast as possible, giving the Russian cannon crews a moving target as they tried to set the fuses on their rounds. While they managed to reach the enemy guns, without support they could not hold them or carry them off, leaving them no choice but to retreat under fire. While the Charge of the Light Brigade was later honored as an example of bravery and discipline, in reality it was a waste of lives to no worthy end.

Retellings of the Battle of Balaclava abound. What makes this book different is the author’s attention to how it might have ended very differently. The book does recount the actual events and does so very well. It goes on to analyze the various commanders’ decisions and looks at how even a few changes could have resulted in a clear British victory that day. There are a number of good appendices providing added information, and the extensive use of participant statements enhances the narrative. There are many accounts from enlisted men that provide a view of the battlefield itself.

The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe (Mark Mazower, Penguin Press, New York NY, 2021, 608 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover)

The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe (Mark Mazower, Penguin Press, New York NY, 2021, 608 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover)

When Greece rose in revolt against the Ottoman Empire in 1821, the prospects for a Greek victory appeared slim. Although its power was gradually waning, the Ottoman Empire was still sufficient to crush the rebellious Greeks in short order, or so it was thought. After years of conflict, though, the Greeks were still fighting, and the war took on a flavor of Christian resistance to Islamic encroachment. Soon Britain, France, and Russia became involved and soundly defeated an Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Navarino. Along with setbacks on land, this was enough to force the Ottomans to abandon the fight and allow Greece its independence.

This is one more of Europe’s wars sunken into relative obscurity, except among devoted historians and students; however, the author’s clear prose and thorough research help bring an important conflict of the 19th century to light in this new work. The story delves into the various military, economic and social factors affecting the start and outcome of the fighting. The war’s anonymity in the modern world is offset by the author’s careful explanations and guidance in showing its relevance to later events and modern Europe.

Short Bursts

Cyberspace in Peace and War, Second Edition (Martin C. Libicki, Naval Institute Press, 2021, $60.00, hardcover) The cyber realm has already seen the first attacks of a new type of warfare, one that many do not understand. This updated work delves into the history and tactics of cyber warfare.

Cromwell Against the Scots: The Last Anglo-Scottish War 1650-1652 (John D. Grainger, Pen and Sword, 2021, $39.95, hardcover) Also known as the Third English Civil War, it was actually the last war between England and Scotland as separate states. This revised edition has an added chapter on the war’s aftermath.

The U.S. Army Infantryman Vietnam Pocket Manual (Edited by Chris McNab, Casemate Books, 2021, $16.95, hardcover) This handbook draws from numerous field manuals, intelligence analysis documents, and after-action reports to provide insight into the experiences of the combat soldier in Vietnam.

The U.S. Army Infantryman Vietnam Pocket Manual (Edited by Chris McNab, Casemate Books, 2021, $16.95, hardcover) This handbook draws from numerous field manuals, intelligence analysis documents, and after-action reports to provide insight into the experiences of the combat soldier in Vietnam.

Break in the Chain: Intelligence Ignored (W.R. Baker, Casemate Books, 2021, $34.95, hardcover) The author served as an intelligence analyst in Vietnam during the 1972 North Vietnamese offensive. He provides expert insight on how information predicting the attack was ignored.

The Sino-Soviet Border War of 1969 Volume 2: Confrontation at lake Zhalanashkol August 1969 (Dmitry Ryabushkin and Harold Orenstein, Helion and Company, 2021, $29.95, softcover) From March to August 1969 the Soviet Union and Communist China fought a short but intense war along the Sino-Soviet frontier. This important volume reveals details of the fighting to the western reader, along with numerous photographs.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments