By Blaine Taylor

Adolf Hitler’s wartime Armaments Minister Albert Speer was right when he termed the Führer’s pilot from 1932 to 1945, Lt. Gen. Hans Baur, an unrepentant Nazi.

Holocaust Denier and Hitler Fan

Indeed, in a postwar interview with Frank Brandenburg, the crusty but still affable German general called Hitler “one of the greatest men the world will ever see, a true genius,” and like author David Irving, denied as well that the Holocaust against the Jews ever happened. The latter was all Allied propaganda, he asserted, designed to besmirch the true record of Nazi Germany’s accomplishments in both peace and war.

There can be no doubt that there was a personal bond between the two men. The Führer was his pilot’s best man at the latter’s second wedding, and they shared both a razor and Russian lice during a wartime trip that almost got them captured by Soviet Army tanks charging their plane’s airfield. At their last meeting on April 30, 1945, Baur implored his leader to let him fly the Reich Chancellor to anywhere in the world he wanted to go—Imperial Japan, Juan Péron’s Argentina (postwar home to many top Nazis), or the Jew-hating Arab countries of the still-volatile Mideast.

One Final Mission For Trusted Pilot

But Hitler was adamant. He would stay in Berlin and die there, committing suicide rather than being captured alive by the Soviet Army and put on display naked in the Moscow Zoo as he feared Stalin would do. He charged Baur with a final mission instead—seeing that Reichsleiter (National Leader) Martin Bormann got out of Berlin safely with some important papers that Hitler had placed in his care. As a parting gift, his grateful Führer presented Baur with a favored personal possession, a famous oval portrait of Hitler’s idol, Prussian King Frederick the Great. The portrait was rolled up and placed with Baur’s knapsack as he fled the Führerbunker on May 1, 1945, under intense Russian shell fire. Separated from the drunken Bormann (whose death was confirmed by a DNA matchup with his remains discovered in 1972 and announced to the world by The Washington Post on May 4, 1998), Baur himself was badly wounded.

Soviets Don’t Believe Baur’s Story

When found by Soviet Army soldiers, Baur gave them his correct name, rank, and the fact that he was Hitler’s personal pilot, thinking that this might gain him immediate medical attention. Instead, it was delayed, and eventually his wounded leg was amputated without anesthetic, by a penknife because a scalpel could not be found. Further, Baur spent the next decade in Soviet prisons and labor camps, constantly in pain and torment from almost daily interrogation on a single topic: Was Hitler alive, and did he, Baur, fly him out of Berlin and then return himself as a cover for this story?

As both Baur and the NKVD (Soviet Secret Police) well knew, the dead Führer’s charred remains had been found in May 1945 right where he consistently said they were: in the bombed-out Reich Chancellery garden. Apparently, Stalin did not believe his own secret policemen and had personally singled out the Führer’s pilot for special attention as a war criminal. Baur was tried and convicted of conspiring against the Soviet Union in 1950 and sentenced to 25 years’ imprisonment.

Early Promise as WWI Flying Ace

Thus has Hans Baur gone down in the history of World War II, as yet another witness to the final days of the Third Reich and of the Führer. However, he was, in fact, much more than that.

Born at Amfing, Bavaria, on June 19, 1897, Baur volunteered for the German Army Air Forces during World War I, and in the British version of his 1958 memoirs, Hitler’s Pilot, he recalled, “Up to the end of the war, I shot down nine French planes, which was the top ace record for pilots flying artillery observation and infantry-support planes.” During the war, Baur received the first of many medals that would later accrue to his star-studded service record from both Imperial and Nazi Germany, Finland, and Croatia, to name but a few.

A mere 21 years old at the end of the war, on January 15, 1919, Baur was one of six pilots selected out of 500 to be the first military air-mail flyers. He joined the von Epp Free Corps to put down a Communist rising in Münich that same year and received his civil air license in 1921. Before he began his 13-year career as Hitler’s Pilot in both peace and war, Baur flew a host of famous passengers, among them the later Pope Pius XII, King Boris of Bulgaria, the president of Austria, and Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini.

He also flew to Paris, Bucharest, Vienna, and Rome, and by the first year of the new Third Reich, 1933, had won many coveted flying awards and logged a million kilometers of air travel as well. He had joined the Nazi Party as member number 48,113 in 1926 after meeting fellow pilot and World War I veteran Rudolf Hess. Two years later, he was promoted by the new German national airline service, Lufthansa, to the rank of flight captain.

Presidential Candidate Hitler Impressed With Flying Ability

Baur’s first piloting of German presidential candidate Adolf Hitler took place on March 3, 1932, according to the German Luftwaffe (Air Force) magazine The Eagle eight years later: “That was excellent, Herr Baur; the experience of an old combat flyer cannot be denied.” (During his first flight, from Münich to Berlin to take part in the 1920 Kapp Putsch [Revolt] that was over when he got there, the Führer had become airsick.)

Now, when time was of the essence, Hitler preferred air travel to that of either road or rail, first because of the number of cities he could reach in which to campaign—“Hitler Over Germany” was the slogan—and second as a better, safer deterrent against assassination, a very real hazard from the German Communists of that pre-Third Reich era.

Candidate Hitler lost both presidential elections that year (a runoff had to be held when the first election proved inconclusive), but when the Führer was appointed Reich Chancellor by the very man who had beaten him in both, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, he established a new government squadron to fly him, Hermann Göring, Hess, and Dr. Josef Goebbels, all members of the Reich cabinet. As squadron commander, it was Baur’s job to select both the pilots and the aircraft for this highly important task that was to dominate the rest of his career.

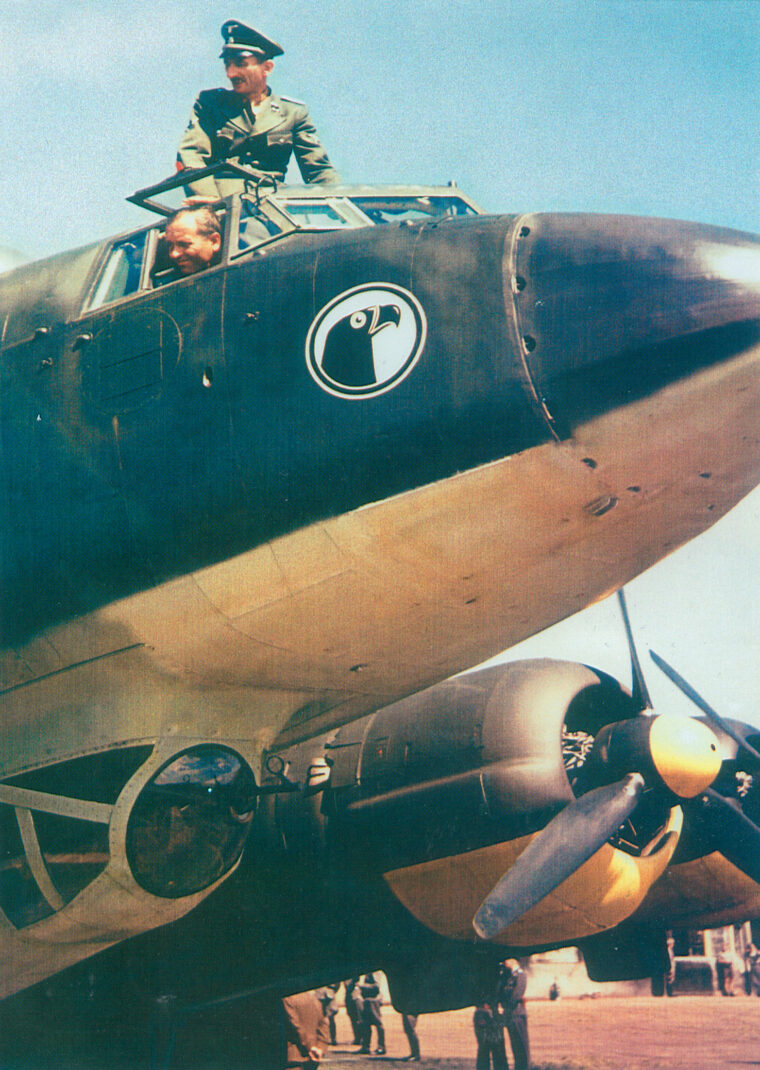

SS Lieutenant General Baur Never Member of Luftwaffe

A member of both the SA (Stormtroopers) and the SS, Baur was never commissioned in the new German Luftwaffe (and thus did not report to its chief, Göring). Instead, in 1936, he was placed on the personal staff of Reichsführer (National Leader) SS Heinrich Himmler. Thus, before the war he wore SS black, and during it the gray uniform of the Waffen (Armed) SS, although he was never a member of that body. On February 23, 1945, he was promoted to his final wartime rank, lieutenant general in the SS, which was also used against him politically by his captors, the Soviets.

Aside from his hand-picked pilots who were stationed in Berlin, the Berghof at Berchtesgaden, and at all of the Führer’s wartime military headquarters, Baur chose the aircraft types the Führer used, the Junkers Ju-52 and Focke Wulf FW 200 Condor, and the one he was assigned at the end of the war but never flew in, the Ju-290. The number D-2600 was assigned to the Ju-52 used as the Führer’s plane, while it was succeeded by Condors Grenzmark and Ostmark.

D-2600 Conveys Participants To Several Historic Events

D-2600 came online in June 1933, as Immelmann and Immelmann IIHitler’s Personal Pilot: The Life and Times of Hans Baur, both named after World War I air ace Max Immelmann, for whom the “Blue Max” (the formal title was Pour le Mérite) medal was also named. It was aboard Grenzmark that Baur twice flew German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop to Moscow, first to sign the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of August 1939, and then the following month after the partition of fallen Poland. During the Polish campaign, Baur flew Hitler in both D-2600 and Grenzmark to inspect the fighting fronts.

In his superb biography, Hitler’s Personal Pilot: The Life and Times of Hans Baur, C.G. Sweeting, former curator of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum, states, “After considerable service … the plane [Grenzmark] was destroyed on December 23, 1941, when it crashed on landing on a snow-covered airfield near Orel, Russia, while delivering a load of Führerpakete, Christmas presents from the Führer, to the German soldiers at the front. Baur was not piloting the plane on that flight.”

Il Duce Was My Co-Pilot

Sweeting also asserts that after Baur became Hitler’s Pilot in 1932, the Führer only flew once without his friend at the controls, while Baur was in Moscow with von Ribbentrop. That flight from Berchtesgaden to Berlin took place on August 23, 1939. During a momentous trip to the conquered Ukraine in August 1941, Baur had a copilot, however, in the person of none other than fellow flyer Benito Mussolini. During this celebrated incident, the nervous Führer congratulated his fellow dictator on his aerial acumen, but was nevertheless relieved when the Duce departed the cockpit.

A similar trip had occurred on June 28, 1940, when Baur flew Hitler and Speer to Paris for an early-morning visit to tour the sights. Had the war turned out otherwise, no doubt the flight would have been replicated in trips to London, New York, Washington, and Tokyo.

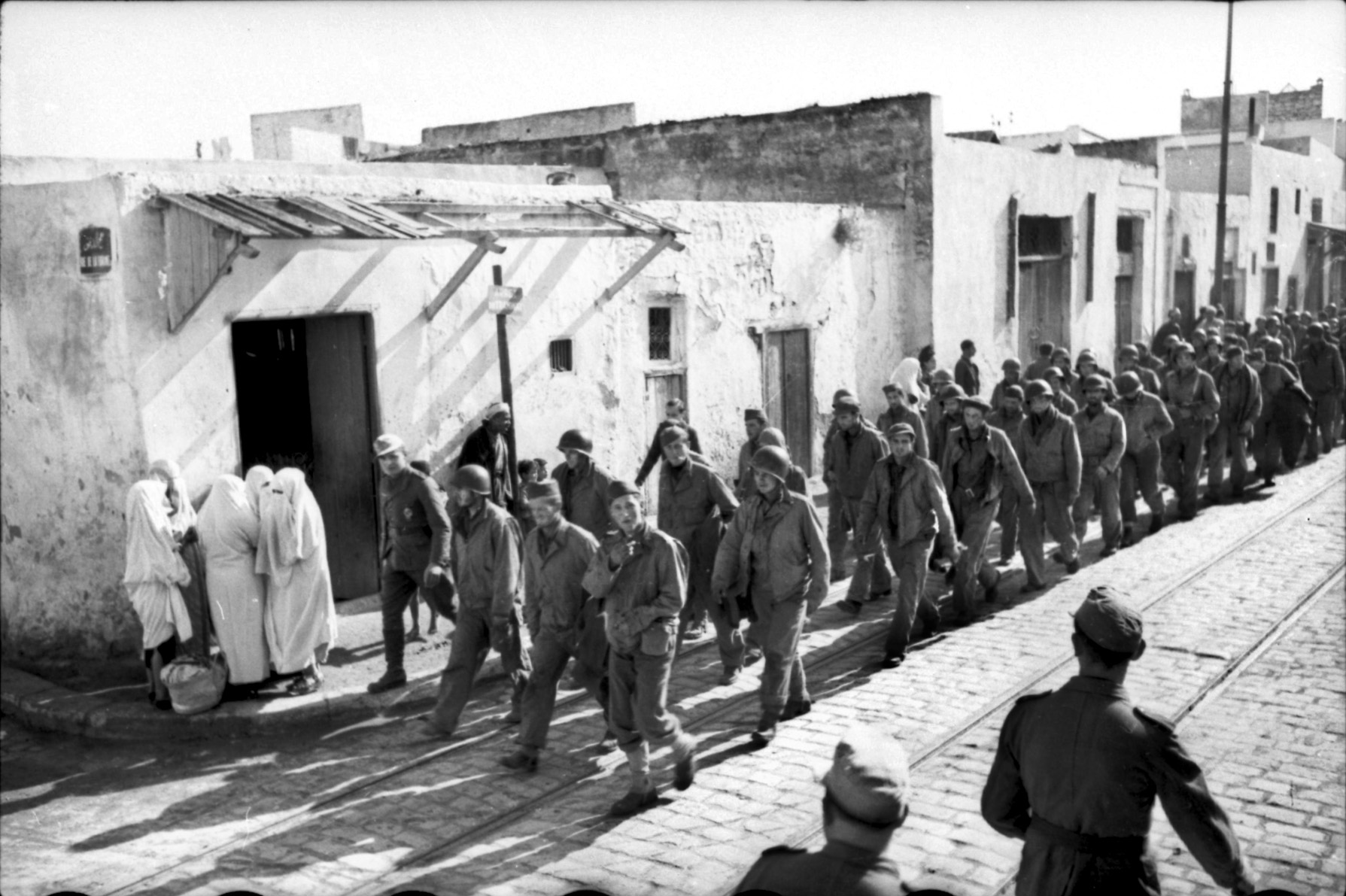

As it was, Baur alone in 1938 flew over Sicily, Malta, Libya, Cairo, and an as-yet-unknown Egyptian hamlet called El Alamein where Field Marshal Erwin Rommel would meet defeat against Bernard Montgomery’s British Eighth Army four years hence. On June 24, 1941, two days after his all-encompassing invasion of Stalin’s Soviet Union, Hitler was flown to his principal military wartime Führerhaupt- quartiere (headquarters), the Wolfsschanze (Fort Wolf) at Rastenburg, East Prussia.

A Busy Period For Fuhrer’s Pilot

Over the next three-and-a-half years, from the adjacent Rangsdorf airfield, Baur would fly Hitler to visit the farflung headquarters of his Eastern Front field marshals or fly them in to see the Führer. He also flew the Führer’s friend, King Boris of Bulgaria.

During his free time, Baur fished in the nearby East Prussian lakes for perch and pike from a most unusual platform. He called it a “floating car” in the 1986 American version of his memoirs, Hitler at My Side. It was a Volkswagen-built Schwimmwagen (Swimming Car) given to him by designer Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, whom he had flown to Russia on a tank inspection mission. At Baur’s death, a portrait present of that flight still resided proudly in his Bavarian home, where he lived with his third wife.

While flying Hitler in Russia aboard a Heinkel He-111, Baur stopped at Kiev. According to Sweeting, Hitler told his pilot, “Baur, it’s bitter cold in your plane. My feet are turning into icicles!” Hitler was not properly dressed for the cold, so Baur offered to get a pair of flyer’s boots for him to wear. Hitler, Führer and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, declined, saying, “I am not authorized to wear them.”

During the cold Russian winter of 1942-1943, Baur took part in the doomed aerial relief mission to resupply the encircled German 6th Army at Stalingrad, which was ultimately forced to surrender nevertheless.

The Führer’s Special Emergency Escape Hatch

In his work, Mr. Sweeting clears up a very interesting point about Hitler’s air travel during the war. “In case it would have been necessary to bail out of his plane, Hitler would have donned his parachute harness in the back of his seat and then pulled a red grip handle on the wall, which released the escape hatch in the floor just forward of his chair. The seat back cushion and the seat bottom cushion were simply connected to the jumper with the parachute harness. The parachute was the manual type, which had to be opened with a small handle which had to be opened by the jumper after he cleared the plane. Hitler then would have jumped down and out of the plane through the escape hatch opening.”

Theoretically, this is all well and good, except for two things—the possibility of human error, and the unexpected. Hitler had not, after all, gone to jump school as paratroopers do. When Hess tried to bail out of his plane over Scotland, the wind stream forbade his clearing the open cockpit with the plane upright. Therefore, he flipped the plane over and fell out. Hess was a trained pilot who nevertheless injured himself on landing and was immediately taken prisoner. It is doubtful that Hitler would have survived such an adventure.

The Final Plane a Technical Marvel

Hitler’s final plane was the Ju-290, which both he and Baur saw together for the first time in September 1943, during an aircraft inspection at Insterburg. As Baur recalled in 1958 in Hitler’s Pilot: “The Ju-290 struck me as specially suited for my purposes. It was a four-engine job, and each engine was of 1,800 horsepower. I was inside this machine and examining it very closely when Hitler put his head through the entrance. I invited him to come in and examine the machine with me, and he did. He was not long in recognizing the advantages of a powerful, long-range, heavily-armed plane that could carry 50 passengers.”

In the summer of 1944, Baur recalled, the plane was converted for Hitler’s use. It had originally been designed as an Atlantic long-range reconnaissance aircraft with a range of almost 4,000 miles. The Ju-290 weighed 40 tons and carried a crew of 14 with heavy armament. A trio of these aircraft were based at the Pocking Airfield, between Braunau and Passau, for the government squadron. Baur noted, “The place where Hitler sat was protected with armor plate, and the safety glass was of a thickness calculated to withstand bullets.” The escape hatch had also been improved. “A powerful hydraulic device was installed capable of opening a special trapdoor at his feet against the strongest air pressure…. We tried this mechanism out repeatedly with a dummy of the correct weight and size, and it always worked satisfactorily.”

A Long and Comfortable Life After Returning Home

Hitler never got to use the Ju-290, for on March 17, 1945, at Munich airfield a flight of American bombers returning from Italy bombed the field and destroyed Hitler’s new plane. “In Berlin, I reported the fate of our Ju-290 to Hitler,” recalled Baur, “but he took it very calmly, just nodding his head.”

Then came May 1, 1945, with Baur wounded in the legs, chest, and a hand. In 1955, two years after Stalin’s death, Baur was sent home, where he received a lifetime pension as a wounded war veteran. He lived peacefully and died at age 95 on February 17, 1993, at Herrsching, Bavaria, having outlived all his former associates in the Nazi régime.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments