By Kelly Bell

Adolf Hitler and his military commanders were feeling a new and unsettling emotion early in 1943—desperation. A year earlier, they had seemed on top of the world as their forces ruled a region that surpassed Rome at its greatest.

The Third Reich had commanded an empire sprawling from the Russian steppes to the Atlantic to North Africa and seemed ascendant on all fronts. Over the past year, it had become a different world as Nazi armies were sent reeling in Russia and Africa, and Allied bombers were reducing the Fatherland’s cities from the air. Still, the German soldier remained an implacable enemy. He would soon strike back in a theater in which his country was not known for supremacy: the sea. A foretaste of this backlash came in February.

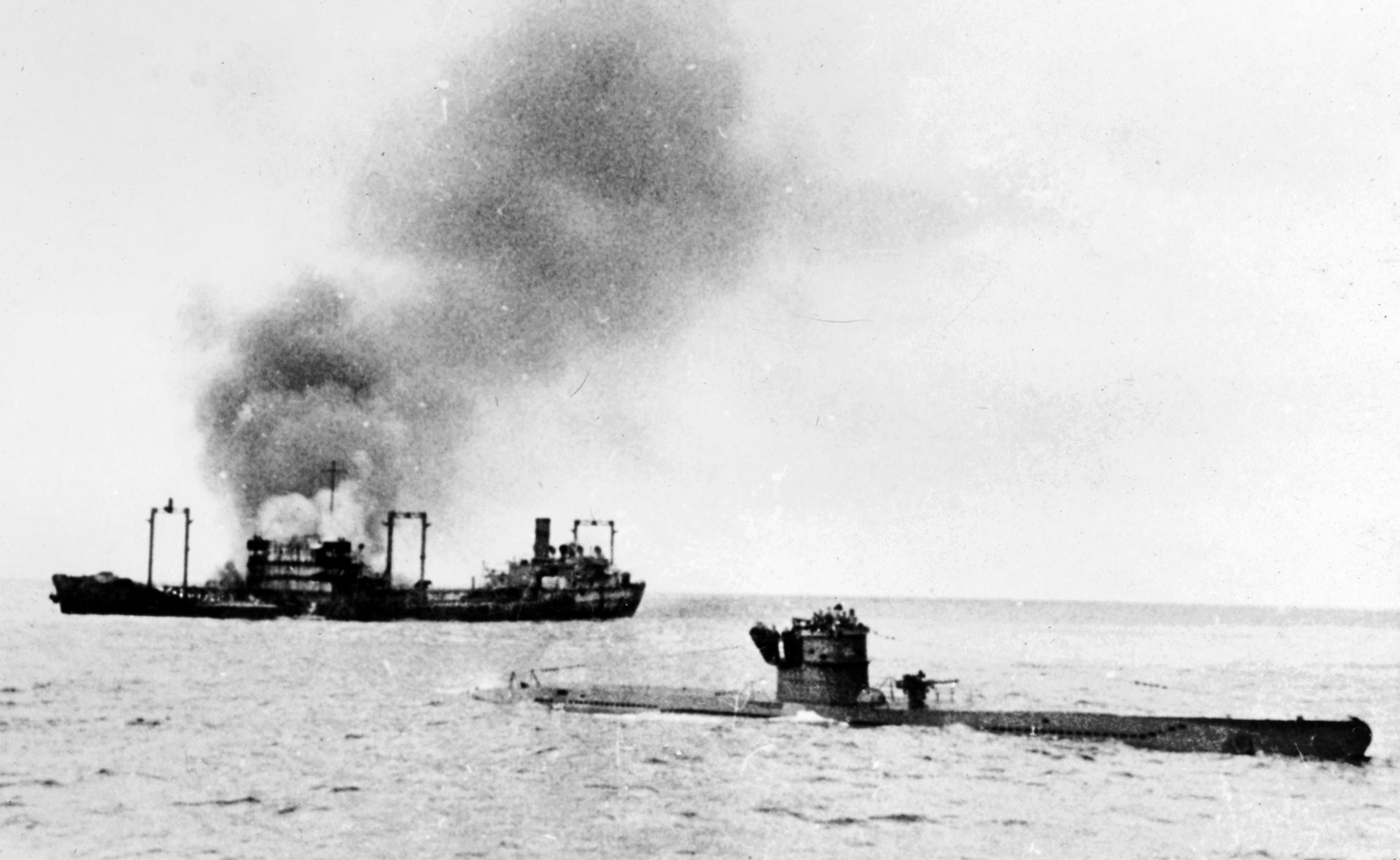

Lieutenant Commander Siegfried von Forstner was a fourth-generation member of his noble Prussian family to make the military his life’s work. Over a 36-hour stretch from February 7-9, he repeatedly prowled his submarine U-402 close enough to Allied convoy SC118 to snipe seven cargo ships from the fleet despite numerous mechanical problems with his U-boat and regardless of Royal Air Force (RAF) B-24 Liberator bombers searching frantically and vainly for him. Forstner maintained his solitary, devastating assault in spite of the humiliated escort’s best efforts, breaking off only when he ran out of torpedoes. As U-402 limped back to occupied France, the Royal Navy ruefully pondered the implications of the actions of this lone, ailing submarine. There were many “what ifs” to consider.

Forstner’s colleagues in the Kriegmarine’s U-boat arm were not about to let their handsome comrade monopolize the limelight. Germany’s submarine skippers were a notoriously competitive fraternity, and as each of them took to the cold North Atlantic in the opening weeks of 1943, they were infused with a determination not to be outdone and to strike a blow desperately needed by the reeling Fatherland.

U-boat paladin Admiral Karl Donitz called his cryptographic section B-Dienst, and in February and March he kept it busy deciphering the deluge of transmissions intercepted from the Allies’ proliferating convoy program. The most significant data concerned two convoys, designated SC122 and HX229, that were departing New York the second week in March. Totaling more than 100 ships, these flotillas were transporting everything from Spam to locomotives. Many of the vessels were, in fact, overloaded and would sink quickly if holed. When he got the news, Donitz quickly commenced laying battle plans.

Fortunately for the Allies, B-Dienst never learned of a third convoy, HX229A, that left New York immediately after the first two. Taking a northerly route to avoid mid-ocean congestion, it churned safely above the congregating submarines. Still, the submersibles would soon find plenty of targets.

Beginning on March 12, Donitz personally assembled history’s biggest-ever submarine fleet to be deployed for a specific combat action. Three “Wolf Packs” composed of 38 U-boats positioned themselves in the North Atlantic in anticipation of the coming merchantmen. Farthest to the west, the first flotilla, nicknamed Raubgraf (Robber Baron,) lined up northwest to southeast south of Greenland. To the east Sturmer (Daredevil) and Dranger (Harrier) formed a north-south row. When they arrived, the convoys would steam into an L-shaped formation that would curl around and encircle them. The Allies, meanwhile, had inadvertently been making Donitz’s job easier.

The significance of U-402’s depredations was lost on the Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff, who had imprudently withdrawn all Consolidated B-24 Liberator four-engine bombers from anti-submarine duty, adding them to the fleets carrying out the burgeoning strategic-bombing campaign over continental Europe. Flying from the American east coast and from the British Isles, the B-24 was the only plane in the Allied arsenal with sufficient range to provide continuous cover for the convoys; Britain-based bombers would take over when those flying from the States did have to turn back. The departure of the ungainly looking but versatile “Flying Boxcars” opened a 200-mile-wide mid-ocean gap in which cargo carriers were out of range of air cover. The submariners would take full advantage. Yet as the battle loomed, the hunters almost lost their quarry’s scent.

SC122 avoided Raubgraf by passing farther south than the Germans had anticipated. At first, HX229 also steamed under the southernmost boats, but late on the stormy night of March 15, U-91 managed to sight a destroyer. Followed by three other subs, it took off in pursuit. Comprising newer ships, HX229 was faster than SC122. Despite being unaware they were being followed, the merchant seamen outdistanced the quartet of wolves. By this time, though, the convoys were nearing the air-cover gap, and easternmost Dranger had received wireless warning of the approaching targets.

Although the Germans knew their prey were in the general vicinity, no cargo carriers were in sight, and there was no way of knowing whether they might change direction. The hunters got the break they needed during the predawn of the 16th. U-653 had been deployed for this action while she and her crew were en route home from a lengthy patrol and had not had time for servicing, rearming, provisioning and refueling. She had just one torpedo remaining and was slowed by a broken-down engine. Realizing his sub was in no state to participate in the coming battle, her skipper had detached from the pack and was slowly steaming eastward on the surface. Quartermaster Heinz Theen was on bridge watch when he saw something suspicious.

“I saw a light directly ahead for only about two seconds,” he later recalled. “I think it was a sailor on the deck of a steamer lighting a cigarette. I sent a message to the captain, and by the time he had come up on the bridge we could see ships all around us.”

Slowed by having just one operable engine, U-635 had been overtaken by fast-moving HX229. After counting 37 freighters, three destroyers, and two corvettes, the submariners realized they and their ailing boat were in a perilous position and fortunate to have not already been spotted. They crash-dived, killed their engine, and listened silently and fearfully as the fleet passed over them.

“We could hear quite clearly the noises of the different engines,” Theen said. “The diesels with fast revs, and the turbines of the escorts making singing noises.”

It took two hours for the convoy to pass. As soon as the engine noises faded, the U-boat resurfaced and broadcast a coded message to the other wolves, informing them of the fleet’s position, heading, and speed.

When the news reached him, Donitz personally coordinated the battle from his new headquarters in Berlin’s bomb-damaged Hotel am Steinplatz. Raubgraf swapped ends and took off after HX229 from behind while Sturmer and Dranger spread out and bore down from dead ahead, trapping the ships in a three-pronged pincer. By dusk on March 16, 1943, the hapless supply flotilla was surrounded.

To make the situation worse for the convoys, the weather had cleared, and the moon was nearly full. The Germans looked out over a vista of highly visible targets. Just two escorts, a full six miles apart, guarded the convoy’s lengthy flank. Like U-653, U-603 had already been at sea for a protracted period when Donitz deployed her for this action. Her skipper, Lt. Commander Hans-Joachim Beertelsman, had just four torpedoes remaining when he steered his boat through the gaping hole between escorts. Three of his torpedoes were Feldapparat (coiled spring) missiles that could be programmed to jet in a straight line for a specific distance and then commence weaving in hairpin loops until either they hit something or their electric engines ran out of power. Issuing a radio warning to his sister subs to stay clear of the vicinity into which he was preparing to shoot, he fired his twisting torpedoes. All three missed, so Watch Officer Rudolf Baltz climbed onto the conning tower and verbally directed the firing of his boat’s last conventional shot. It hit the freighter Elin K amidships, sending her under with 7,500 tons of precious manganese and wheat. By some miracle none of her crew were lost, but for the rest of the convoy the havoc was just getting started.

Minutes later, Lt. Commander Helmut Manseck in U-758 picked off two supply vessels just seconds apart, and as more U-boats penetrated the convoy’s perimeter, explosions began to banish the darkness throughout the sprawling marine battlefield. Just before daybreak, the Irene du Pont went down after taking two hits. She was the 10th ship sunk or crippled before dawn. The Germans were still closing in on all sides, and this was not the only battle going on.

About 120 miles northeast of bleeding HX229, convoy SC122 was under fire as a lone wolf attacked. Her crew had nicknamed U-338 the “Wild Donkey.” They were completely new to this game and having a great time learning. The sub was fresh out of the shipyard, and her crew were fresh out of training. Her skipper, Captain Manfred Kinzel, had started the war as a Luftwaffe pilot, only recently switching to the navy. His men were as inexperienced as he, on their first voyage and without one old salt among them. Eager for the thrill of their first combat, they had been steaming full speed to join the assault on HX229 when they blundered into SC122. Like its counterpart, this convoy was poorly guarded, with only two destroyers, five corvettes, and a frigate as escorts.

Kinzel had a great idea. Noting his targets’ slow speed, he devised a tactic a seasoned skipper would likely have considered too risky. Cutting in front of and turning onto the same heading as his quarry, he slowed to a snail’s pace and allowed the leading escorts to overtake him. Never dreaming the Germans would attempt anything so foolhardy, the warships’ crews were not watching for it and passed blithely on either side of the U-boat. By 2 a.m., U-338 was just one mile in front of the freighters and turned to face them.

The previous day’s storms had damaged the connection between the conning tower’s sighting glass and the torpedo calculator, making a standard attack impossible. The youthful submariners improvised.

“We had to make the attack partly by eye, and had to aim the torpedoes by turning the boat onto each target,” Watch Officer Lieutenant Herbert Zeissler later explained. “We fired the first two at the right-hand ship we could see. We then had to turn to port to aim the second pair at the lead ship of the second column.”

Firing twice at each target, the Germans sank both even though one torpedo missed, but this one ripped open and sank the ship behind the first one hit. Crewmen on several freighters fired flares to illuminate the U-boat and opened fire on her with antiaircraft machine guns. Slewing to starboard, Kinzel fired an aft shot blindly into the convoy and dove to safety. This last missile, after a full six minutes, lucked into and sank a merchantman at the very back of the fleet. It had taken Wild Donkey and her cast of fearless rookies less than 10 minutes to chalk up their first four kills. They celebrated with a raucous breakfast of sausages, strawberries, and ice cream. They could not hear the screams of 40 Dutch and British seamen drowning in the freezing swells above them. Even then, SC122’s bloodletting was not over.

By 9 a.m., the convoy was approaching the end of the air-cover gap 900 miles west of Greenland, and a single plane arrived to fly ant-submarine patrol as Kinzel resumed hunting. By noon the aircraft had to depart to refuel, not returning for two hours. U-338 prowled back into the flotilla from its port side and fired three shots at a Panamanian freighter. One round hit dead center, literally tearing it in two. Two escorts managed to get a fix on the raider’s position and set out after her, but the jubilant Germans crash-dived to almost 700 feet. Kinzel may not have been aware that his boat was not designed for such depth, but he did know the Allies’ depth charges could not be set to explode deeper than 550 feet, and he was seeking safety in the deep. In any case, Wild Donkey was brand-new. This was her first voyage, and her welds, bolts, and fittings were fresh and snug. She easily held up under the water pressure of the Atlantic depths while the novices inside her delightedly counted 27 muffled blasts far above them.

That afternoon HX229 also steamed out of the air gap, but there were still too few planes to cover so many ships, and U-384 sank two more. By the evening of the 18th, however, a new Allied technological innovation would make itself felt.

By this point, there were sufficient air patrols to threaten the wolf packs, but when a rain squall blew in, the skipper of U-384 figured this dirty weather would protect him as he surfaced in hopes of spying more targets. What he and the other submariners were unaware of was that their enemy’s aircraft had just been equipped with new radar sets that the subs’ Metox radar detectors could not give warning of in time. This new radar could sniff out surfaced submarines from 12 miles away and was unaffected by weather. A Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress equipped with this new device attacked U-384 out of the clouds, dropping four depth charges that blew the U-boat to bits. Even then, the battle was not over.

With the convoys nearing their destination, the proliferating air-and-sea escorts made further U-boat attacks too risky, but the crew of the freighter Mathew Luckenbach played right into the wolves’ fangs. The previous night had been a very long one for Luckenbach’s crew as they watched their sister ships go down one after another. Losing their collective nerve, they held a spontaneous, predawn pow-wow and decided the convoy was too conspicuous to predatory eyes. They voted to abandon it and strike out on their own. Stoking their boilers, they pulled away from HX229. By full daylight they were alone and vulnerable.

Like Kinzel, Lt. Commander Herbert Uhlig was in his first battle, but unlike his colleague he had found no targets in this sprawling fight that now appeared to be over. Having received news of U-384’s fate, he was running his own U-587 barely submerged when the Luckenbach suddenly appeared in his periscope at a range of 4,000 yards. The ship was bigger than she looked to his inexperienced eye, resulting in his miscalculating the range to be just 1,800 yards. Firing three torpedoes, he eagerly timed their runs. He was disheartened when his estimated time of impact passed uneventfully, but almost two minutes later he and his crew were startled by booming reports as two of the fish lucked into the hapless merchantman. Luckenbach did not sink, but drifted aimlessly while belching smoke. A U.S. Coast Guard cutter responded to her wireless call and rescued her 68 unwise crewmen.

Uhlig waited until dark, when the escort ships and patrol planes departed, and then moved in on what he assumed would be his first kill. It did not happen.

“Only moments before my command to fire she was hit by the torpedo of another boat and sank quickly,” he later groused.

And even now, the battle was not quite over.

Wild Donkey’s joyful youngsters were hanging up five victory pennants as they steamed into the Bay of Biscay. An RAF Halifax bomber, using its new radar, detected the sub and drew a bead on her. With insufficient time or depth to dive to safety, the submariners manned their 88mm deck gun and shot their assailant from the sky. One man, the New Zealander flight engineer, managed to bail out. Kinzel plucked him from the drink and presented him as a soggy, live victory pennant.

Back in Berlin, a delighted Donitz pronounced Wild Donkey’s adventure as “the greatest success ever achieved in a convoy battle.” Along with her sister subs, she had been part of Nazi Germany’s greatest-ever naval victory. These U-boats had destroyed 141,000 tons of sorely needed shipping during their four-day, 600-mile rampage. The Allies were taken totally aback, not only by Donitz’s unanticipated ability to read their mail, but also by the prolonged period during which he was able to maintain his U-boats in the combat zone. The Germans had recently introduced submarine Type XIVA, another bitter surprise. Designed for resupply rather than battle, each of these “Milk Cows” could carry 432 tons of fuel so that attack subs could replenish their tanks at sea rather than having to return to port. Deploying two Milk Cows along with his wolves, Donitz ensured the U-boats could savage the convoys far longer than the Allies had thought possible.

Twenty-two merchantmen had gone down during the mid-Atantic March massacre. Had the Kriegsmarine been able to maintain this rate of attrition, it would have outstripped even the combined industrial capacity of America and England to construct cargo carriers. Nobody challenged a Royal Navy representative when he said, “The Germans never came so near to disrupting communication between the New World and the Old as in the first 20 days of March.” Yet the mass sinking would be an isolated incident.

The United States geared more and more of its massive industrial strength to the war effort. Multitudes of B-24 Liberators were rolling off the assembly lines. Soon, there would be enough both to bomb Germany and fly cover for convoys. With the patrol planes equipped with the new radar sets, it was becoming unsafe for U-boats to stay on the surface long enough to locate targets. Also, Donitz was not the only one reading other peoples’ mail.

As 1943 wore on, Axis submariners had increasing difficulty locating convoys even as colossal volumes of war materiel flowed into Britain and Soviet Russia. Donitz knew the merchantmen were there, but his sea wolves could not find them. At first, he suspected high-level treason and had all his senior officers investigated, but these inspections revealed nothing but a few illicit French mistresses. No one appeared to be passing information to the Allies.

The Brits called their new system “Huff-Duff.” By installing sets both on land and shipboard, operatives were intercepting U-boat wireless transmissions at multiple, widely separated locations and using triangulation to locate wolf packs.

His Majesty’s decoders at the Bletchley Park cryptographic facility outside London had for some time been capturing radio signals and warning convoys away from danger spots. Still, the crafty U-boat chieftain sometimes outwitted his enemies.

In January 1942, Donitz had discarded the Hydra cipher, replacing it with a new device called Triton, drying up the flow of information to the Royal Navy and resulting in the decimation of several convoys. A year later, he correctly suspected the Allies had broken the Triton code, so on March 8, 1943, he threw it out and implemented the sophisticated Enigma machine. Enigma used four coding cylinders rather than the previous device’s three. This quadrupled the possible rotor sequences. Using new electronic calculators (the ancestors of digital computers), British codebreakers took just 10 days to unravel the new cipher, but this was too late to save SC122 and HX229.

Less high-tech innovations were also making themselves felt. Soon after the March battle, convoy escort ships began carrying the new Hedgehog anti-submarine armament. Firing two dozen 32-pound bombs up to 250 yards in front of a warship, this weapon gave escorts a much wider field of attack than that provided by depth charges. Hedgehog explosives did not use depth settings, exploding only when they struck something solid such as a submarine or the sea floor. This made it possible to immediately reestablish sonar contact after missed shots, negating the old submariner trick of hiding in the field of bubbles produced when depth charges exploded.

Other developments were airborne. The March mayhem had impressed upon the Western Allies the importance of anti-submarine air cover. By May, the number of Liberators assigned to protect the convoys had grown from 20 to 70, and every plane was fitted with extra fuel tanks that enabled the B-24s to remain in the air up to 16 hours. Warship escorts were also evolving. The U.S. and Royal navies began installing improvised flight decks on some of their larger freighters and oilers. By teaming these hybrids with destroyers and sub chasers the Allies produced a new breed of task force: the convoy support group.

Should undersea raiders be detected or reported even at extreme range, these five- or six-ship flotillas could either converge on nearby submarines or leave their convoys in the care of aircraft and standard destroyers and strike out independently after subs, returning as soon as the threat was chased off or eliminated. These fast-moving groups could also race to any part of a convoy that was attacked.

Each support group also carried some of the Royal Air Force’s elderly Fairey Swordfish torpedo planes. These obsolete biplanes crippled battleship Bismarck in the spring of 1941 and repeatedly proved their worth as sub killers. Carrying newly developed acoustic torpedoes that homed in on U-boat engine noises, they became a submariner’s nightmare.

All these additions to the Allied arsenal demonstrated their devastating effectiveness in a battle that began on May 4, 1943. Convoy ONS5 was headed west, empty after delivering its load, when it blundered into 30 U-boats that were maintaining radio silence. A storm had scattered the cargo carriers, and several escort vessels had been forced to depart for Newfoundland for refueling.

Charging into the fleet, the raiders quickly sank nine ships, but as they regrouped for a second attack, a dense fog rolled in, hiding their targets. At this point, additional escort warships—armed with the innovative 10-centimeter radar sets—arrived. The March mauling was still a painfully fresh memory as the destroyers charged straight into the wolf pack, sinking two boats by ramming and another two with depth charges.

The U-boats backed off but remained close until the weather cleared. Still, they could not find an opening in the aggressive escort fleet’s perimeter. On the 6th, a second, Liberator-accompanied escort force arrived from Newfoundland and sank three more U-boats. The shaken survivors broke off and retired.

This setback held ominous implications for the Third Reich. March’s smashing naval victory was fleeting and gave way to a reckoning in the Atlantic only weeks later.

The exploits of Dranger, Raubgraf and Sturmer represented the zenith of success for Nazi Germany’s naval forces. There would be no more great victories for the Kriegsmarine, and its U-boat arm would suffer the highest percentage of casualties of any branch of the Wehrmacht. Like their Fuhrer, thes gray wolves of the Atlantic were doomed.

Author Kelly Bell has been researching and writing on topics related to World War II for decades. He resides in Tyler, Texas.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments