By Michael E. Haskew

Even after their stunning defeat at Midway in early June 1942, senior commanders of the Imperial Japanese armed forces were resolute in their grand plan to extend their defensive perimeter in the Pacific.

Soon, Japanese attention turned away from the Central Pacific, toward the south. Major Allied bases in that region posed a threat to Japanese security and the continuing exploitation of the natural resources of the Dutch East Indies, which had been one of the nation’s primary reasons for going to war.

From their bases in Australia and elsewhere in the South Pacific, the Americans and their allies threatened Japanese interests. Therefore, a decision to mount a land assault against Port Moresby from the landward side on New Guinea was coupled with a renewed effort to secure the expansive defensive perimeter that included the Solomon Islands chain, 10 degrees below the equator, due west of New Guinea, northeast of Australia and New Zealand, and northwest of American bases in the New Hebrides.

In January 1942, the Japanese seized and began fortifying the major harbor of Rabaul on the island of New Britain in the Bismarck archipelago. In conjunction with this security initiative, orders were given to build a seaplane base on the small island of Tulagi in the Solomons and an airstrip at Lunga Point on the island of Guadalcanal, 22 miles to the south across Sealark Channel. In the coming months, fighting would rage in the Solomons, and Sealark Channel would become “Ironbottom Sound” because of the number of ships sunk there.

Although their resounding triumph at Midway had evened the odds in the Pacific War and bought time for American forces to gain strength for the long, fighting road to Tokyo, the news that the Japanese were constructing facilities that could threaten communication and supply lines that were vital to their interests in the South Pacific prompted senior American commanders to act. If the Japanese were allowed to firmly establish airstrips in the Solomons, American bases would be within range of their bombers and fighters.

In the summer of 1942, Operation Watchtower, initially aimed at Tulagi but later expanded to include Guadalcanal and the islands of Gavutu and Tanambogo, was set in motion. True to their directive as first to fight, U.S. Marines were selected to undertake the first American ground offensive in the Pacific War. Vice Admiral Richard L. Ghormley commanded the South Pacific Area, while naval Task Force 61 was under the command of Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, the amphibious forces were led by Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, and the 1st Marine Division, commanded by Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, was slated to land at Guadalcanal and Tulagi.

The invasion force assembled near Fiji and set sail for the Solomons on July 31 after conducting a lackluster training exercise at Koro Island. August 7, 1942, was slated as the landing date.

Although inexperienced, since many of its combat infantrymen had only enlisted in the military after Pearl Harbor, the 1st Marine Division was a powerful fighting force of 19,000 troops. Two Marine regiments, the 5th under Colonel Leroy P. Hunt and the 1st under Colonel Clifton B. Cates, were to seize the airstrip. The 11th Marines, commanded by Colonel Pedro A. del Valle, and the 3rd Defense Battalion were to provide support and exploit early gains. The total strength assigned to Guadalcanal amounted to just over 11,000 men. Across Sealark Channel, the 1st Marine Division’s assistant commander, Brigadier General William H. Rupertus, commanded roughly 2,400 Marines for the capture of Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo, including the 1st Raider Battalion under Lt. Col. Merritt A. “Red Mike” Edson, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines under Lt. Col. Harold E. Rosecrans, and the 1st Parachute Battalion commanded by Major Harold E. Williams.

For the Marines, the Solomons Campaign would present a new kind of war. Six months of savage fighting loomed ahead, against the determined Japanese enemy, the fetid jungles of an almost-uninhabitable island, and the ravages of malaria and other tropical diseases. As the date for the landings approached, Vandegrift wrote to his wife, “Tomorrow morning at dawn we land in our first major offensive of the war. Our plans have been made and God grant that our judgement has been sound … whatever happens you’ll know I did my best. Let us hope that best will be good enough.”

When the 5th Marines stormed ashore on Guadalcanal at 9:09 a.m. on August 7, they were surprised to encounter virtually no resistance. Only about 2,500 Japanese troops and Korean laborers were present on the island, and they had melted into the jungle during the previous days’ preinvasion bombing and the subsequent naval barrage. Quickly, the Marines crossed the Ilu River and established a beachhead 2,000 yards long and 600 yards deep. The following day, they advanced the last 1,000 yards and took the airstrip against little opposition.

Meanwhile, the early going at Tulagi was anything but easy. The defenders there were few in number, only about 350 troops of the 3rd Kure Special Naval Landing Force and about 540 support personnel of the Yokohama Air Group along with a handful of construction workers. However, they were well entrenched and motivated. Nearly 1,000 men of the Yokohama Air Group were on Gavutu and Tanambogo as well.

Tulagi was secured by the afternoon of August 8, but the Marines there endured heavy resistance, particularly as Edson’s Raiders reached high ground overlooking the island’s harbor. During the night of the 7th, the Japanese launched several counterattacks, and the next morning Marine reinforcements assisted in the reduction of troublesome enemy machine-gun and mortar positions. More than 150 Marines were killed or wounded in the action, while only three Japanese prisoners were taken. The rest of the defenders died fighting. Gavutu and Tanambogo were captured at a cost of 70 Marines killed and 87 wounded, while the Japanese suffered more than 500 dead.

The American landings in the Solomons took the Japanese high command by surprise, and in the days that followed the response to the offensive was piecemeal. Rather than the sledgehammer blow that they were capable of delivering against the Americans, the Japanese chose to commit only enough forces to deal with what they considered a minor threat. Their failure to recognize the scale of the Solomons thrust contributed mightily to their eventual defeat. By the evening of August 8, the Marines were ashore on Guadalcanal along with artillery and supporting weapons. They numbered more than five times the strength that the Japanese had estimated during the early hours of the operation.

The initial Japanese response to the Guadalcanal landings included air attacks from Rabaul and naval retaliation. During the arduous campaign, several major engagements between warships of the U.S. Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy swirled around the embattled southern Solomons. During the first of these, on the night of August 8, a Japanese task force devastated Allied warships tasked with guarding the approaches to the beachhead. The U.S. cruisers Quincy, Vincennes, and Astoria were sunk along with the Australian cruiser Canberra.

The disastrous Battle of Savo Island compelled Admiral Fletcher to inform Ghormley that his aircraft carriers were vulnerable. Offshore air support for the Marines could not be sustained. It followed that Turner had to pull his amphibious and supply vessels out, as well. On August 9, the naval support began to withdraw, some of the transports with vital supplies still aboard. The Marines on Guadalcanal had only 17 days’ rations available, and the headquarters element of the 2nd Marines was unable to get ashore on the island until the end of October.

Vandegrift and his subordinate commanders were flabbergasted, but the Marines proved resourceful. They scrounged abandoned Japanese food and materiel, conserved and rationed what they had, dug in along the Ilu toward nearby high ground, and got busy finishing the half-completed airstrip begun by the Japanese. They named the airstrip in honor of Major Lofton Henderson, who had lost his life leading Marine squadron VMSB-241 during the recent Midway battle.

Within a week of the Marine landings, Henderson Field was operational. Control of the airstrip meant that fighters and bombers could defend against Japanese air raids and possibly interdict the enemy delivery of supplies and reinforcements. It also meant that the Marines might expect some resupply of their own and that wounded could be evacuated. From the senior officers on land and sea to the lowliest private, everyone knew that control of Henderson Field was the key to victory at Guadalcanal and in the Solomons.

When the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo began to stir in response to the Marine encroachment at Guadalcanal, the Seventeenth Army under Lieutenant General Haruyoshi Hyakutake, already engaged heavily in the fighting on New Guinea, was tasked with eliminating the American lodgment. Hyakutake ordered the 35th Infantry Brigade, under Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi, to step into the breach. Kawaguchi selected an elite unit then based at Guam, the 28th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Kiyono Ichiki, to land on the island and wipe out the American Marines.

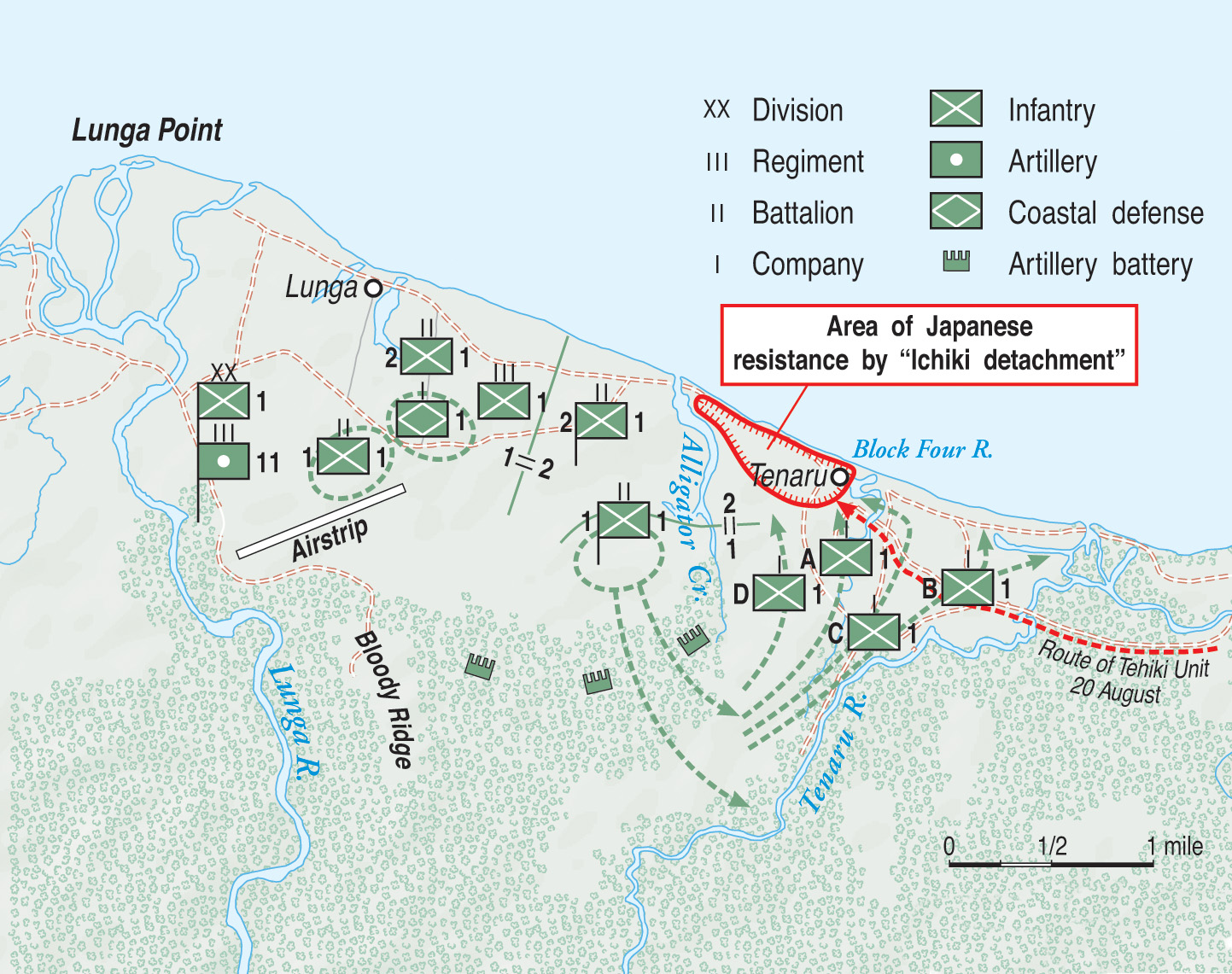

By August 18, six destroyers had delivered Ichiki and nearly 1,000 men to Guadalcanal. A Marine patrol got the drop on a Japanese reconnaissance party and brought back intelligence that confirmed what the Americans had known all along: A determined Japanese attack was coming soon. Colonel Cates ordered his defensive lines lengthened along the Ilu River, nicknamed Alligator Creek by the Marines, and incorrectly identified on Marine Corps maps as the Tenaru. The 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines defended a perimeter that stretched 2,700 yards from the coast at Lunga to the river.

Ichiki assembled his command and issued orders to hit the Marines between the Ilu and Lunga Point on the night of August 21. Once the Marine line was cracked, the Japanese infantry would split, seizing Henderson Field and reducing an enemy defensive position at Lunga Point. Ichiki was supremely confident as he sent his men into battle.

Private John L. Joseph of Company G, 2nd Battalion watched the river intently. He was startled to see the silhouette of a man appear to rise directly out of the water. As the enemy soldier crept closer to Joseph’s foxhole, the Marine shot him in the face. Soon the entire Marine line was alerted, spitting fire at Ichiki’s soldiers as they made for a sandbar in the midst of the river. About 2 a.m., a green flare lit the night with a sinister glow, illuminating a cluster of Japanese troops that were making their way forward.

Marine machine guns and Springfield Model 1903 rifles chattered and barked. Artillerymen packed their 37mm anti-tank guns with canister rounds, effectively turning the weapons into oversized shotguns. When the canister rounds exploded, they spewed lead balls in every direction, tearing great swaths through the Japanese infantry. Despite horrific casualties, Ichiki’s men were relentless, and the colonel committed the balance of his forces to the fight. Several Marine positions were overrun, but the line held.

During the night, repeated Japanese thrusts were repulsed, and near dawn an effort to outflank the Marines was cut to ribbons by the concentrated fire of .30-caliber machine guns, rifles, and 75mm shells from the 3rd Battalion, 11th Marines artillery. The enemy force was pinned down, and as dawn broke Colonel Cates and his subordinates held a hasty war council.

“We aren’t about to let those people lay up there all day,” groused the division operations officer Colonel Gerald C. Thomas. Cates replied, “We’ve got to get them out today!”

Lieutenant Colonel Lenard B. Cresswell’s 1st Battalion, 1st Marines crossed the Ilu upstream and then hit the enemy position from the north, rolling up the Japanese left flank. Joining in the assault was a platoon of five M3A1 Stuart light tanks under Lieutenant Leo Case of Company B, 1st Tank Battalion. Lieutenant Nick Stevenson led Company C, one of four Marine companies engaged in the flanking maneuver, and chewed up a platoon of Japanese soldiers. The enemy force was squeezed into a tightening triangular perimeter, and the tanks ravaged the Japanese, grinding some of the hapless enemy soldiers beneath their treads and blasting others with 37mm shells and machine-gun fire.

Author Richard Tregaskis, whose book Guadalcanal Diary brought the story of the island battle home to millions of Americans, watched the tanks work through a stand of palm trees. “It was fascinating to see them bustling amongst the trees, pivoting, turning, spitting sheets of yellow flame …. We had not realized there were so many Japs in the grove. Group after group were flushed out and shot down by the tanks’ canister shells.”

When Cates became concerned that the tanks were too exposed, he ordered Case to pull back. The lieutenant’s blood was up, and he responded tersely, “Leave us alone! We’re too busy killing Japs!”

As the erroneously named Battle of the Tenaru River petered out, 800 Japanese soldiers were dead, while only 15 were taken prisoner. The Marines lost 34 killed and 75 wounded. Ichiki burned his regimental colors and shot himself.

During this period, the naval and air war off Guadalcanal intensified. The naval Battle of the Eastern Solomons was fought August 24-25, resulting in a tactical draw as the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise was damaged while the Japanese suffered damage to a light carrier and the loss of many planes and trained aircrews.

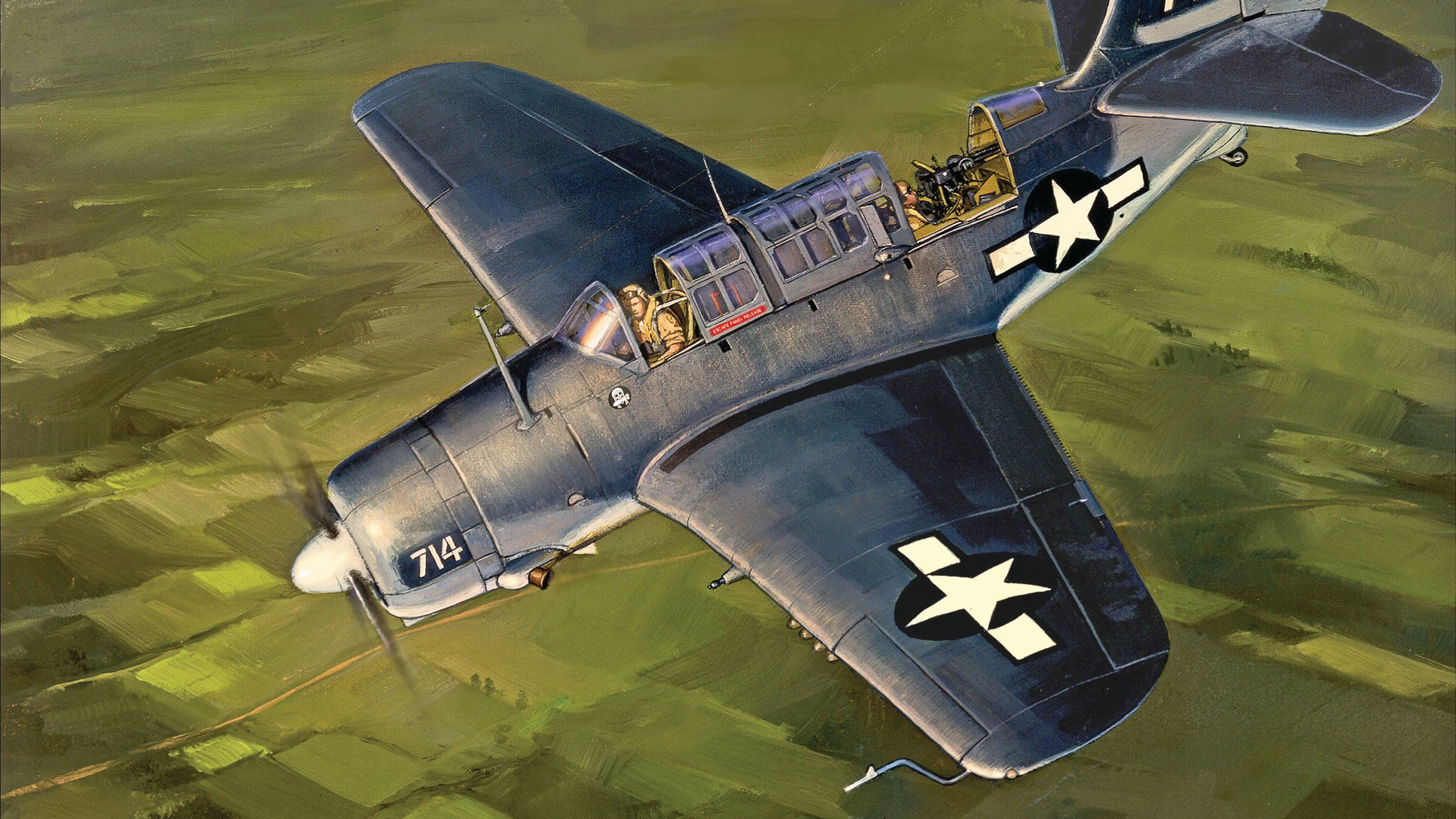

During this naval battle, the pivotal role that Henderson Field was to play in the campaign came sharply into focus. The Allied codename for Guadalcanal was “Cactus,” and on August 20, the first planes of Marine Air Group 23 (MAG-23) landed on the embattled island. These were the 19 Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters of Marine Squadron VMF-223 and the 12 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers of VMSB-232. At the end of the month, these planes were joined by two more squadrons, the fighters of VMF-224 and the bombers of VMSB-231. Along with Bell P-400 Airacobras of the Army’s 67th Fighter Squadron, these intrepid pilots and their planes came to be known as the Cactus Air Force.

The struggle for superiority in the air above Guadalcanal became desperate, and the day after his arrival, Captain John L. Smith, commander of VMF-223, shot down a Japanese Zero. Marine pilots quickly became proficient aerial duelers, and their number of kills climbed steadily. Cactus Air Force planes downed 16 enemy aircraft during a raid on September 24. During that twisting and diving dogfight, Captain Marion E. Carl shot down three enemy planes. Carl was one of only a few land-based fighter pilots who had flown during the Battle of Midway and lived through the ordeal. He went on to finish the war as one of the Marine Corps’ top-scoring aces, with 18½ victories.

During three days of aerial combat from August 29-31, Marine Wildcat pilots shot down 29 enemy planes. Nevertheless, Japanese raids seriously damaged Henderson Field and destroyed much-needed supplies of ammunition and aviation fuel. During the air melee on the 31st, four Wildcats were shot down.

The leading fighter ace of the early campaign in the Solomons was Marine Captain Joseph J. Foss of VMF-121, who received the Medal of Honor for his combat exploits. His citation read in part:

“For outstanding heroism and courage above and beyond the call of duty as executive officer of Marine Fighting Squadron 121, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, at Guadalcanal. Engaging in almost daily combat with the enemy from 9 October to 19 November 1942, Captain Foss personally shot down 23 Japanese planes and damaged others so severely that their destruction was extremely probable ….”

Foss was said to have damaged at least another 14 Japanese planes, and doubtless some of these were shot down. He ended the war with 26 confirmed kills. Four other Marine fighter pilots, Captain Jefferson J. DeBlanc of VMF-112, Major Robert E. Galer of VMF-224, and Captain Smith of VMF-223 received the Medal of Honor. Collectively, these four pilots destroyed 67 Japanese aircraft.

On the ground, General Vandegrift took the opportunity to consolidate his available infantry strength, transferring the Raider and Parachute battalions under Lt. Col. Edson and the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines to Guadalcanal from Tulagi. At the same time, the Japanese had deemed the continuing daylight runs of troops to Guadalcanal too hazardous due to the American air presence at Henderson Field. As an alternative, they undertook nocturnal supply-and-reinforcement missions down the narrow Solomons channel, nicknamed “The Slot,” and delivered thousands of troops to the embattled island. Japanese cruisers and destroyers also shelled Henderson Field and other Marine positions nightly. The Marines dubbed the supply runs under cover of darkness the “Tokyo Express.”

Early in their deployment, the Marines had fortified positions along high ground facing west toward the Matanikau River, and Vandegrift fully expected a renewed Japanese effort to capture Henderson Field. He knew that the enemy was growing stronger, and by early September Kawaguchi’s 35th Infantry Brigade was on Guadalcanal in force.

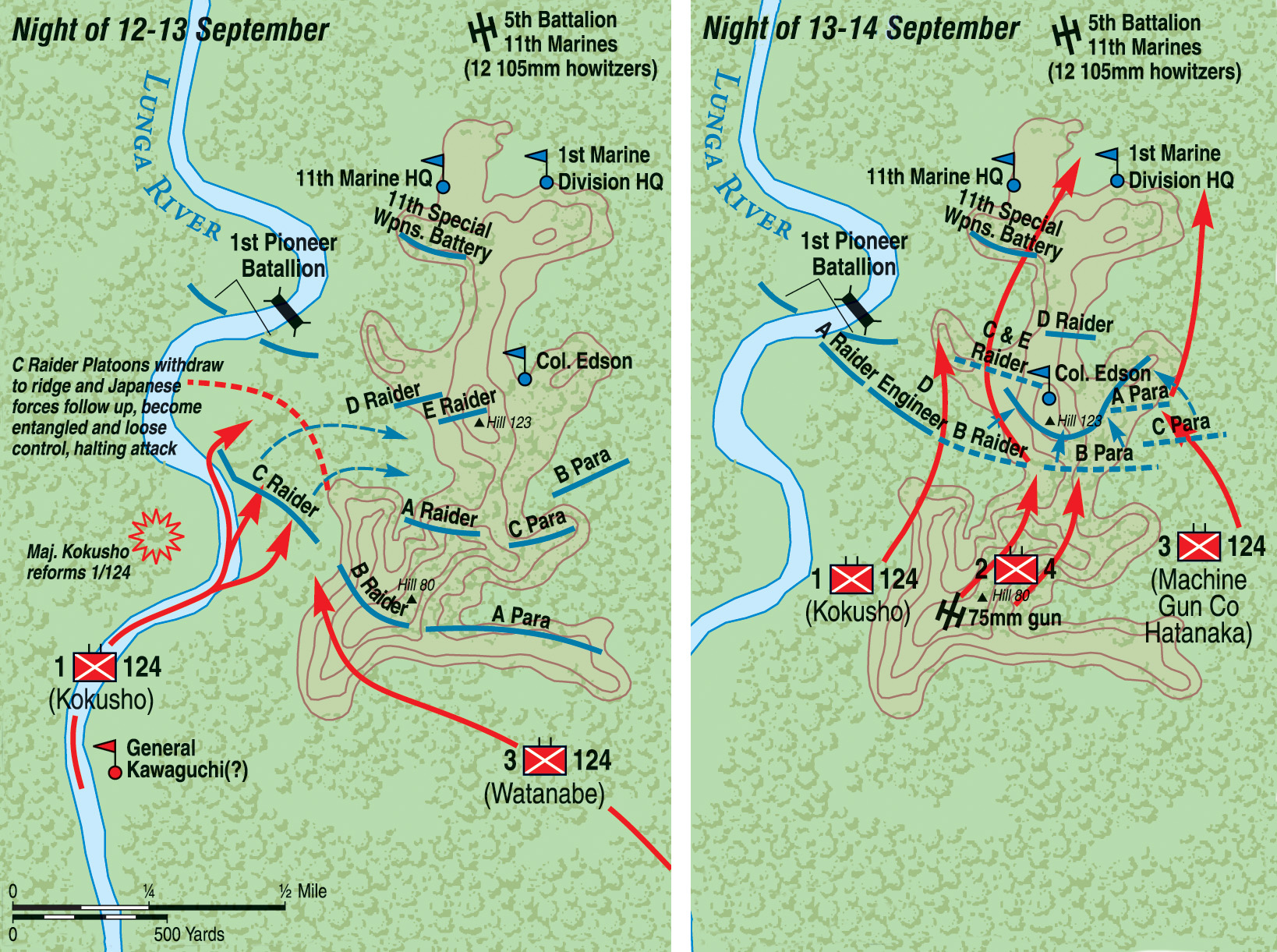

Kawaguchi believed that the Marines had strengthened their flanks at the expense of the center of their line, and with 2,000 troops he intended to attack straight into the belly of the Marine defenses directly at Henderson Field. Although the success of Kawaguchi’s plan depended on Vandegrift being preoccupied with his flanks, the Marine commander was convinced that Henderson Field was Kawaguchi’s objective. He told Edson to place his Raiders and Parachute troops along a ridge that stretched within a mile of the vital airstrip.

Edson, who later remarked that he was “firmly convinced that we were in the path of the next Jap attack,” ordered his men to dig in on the forward slopes, and by the evening of September 10, they were in place. Two days later, a Japanese patrol brushed the defensive perimeter, and the Marines knew that the big enemy push was only hours away.

At 9 p.m. on the 12th, the storm broke. Japanese soldiers rushed from the thick jungle foliage and assaulted Edson’s left flank. They were repulsed but undeterred. Moments later a second charge hit the Marines’ right flank. This time enemy troops got into some Marine foxholes, and the fighting was hand-to-hand before the attackers faded away. A third charge hit the tired Marines once again and failed. After five and one-half hours of combat, Edson radioed Vandegrift that the Marines would hold the line. No one, however, believed the fight was over.

Edson encouraged his troops and told them, “They were just testing. They’ll be back.” He added, “You men have done a great job, and I have just one more thing to ask of you. Hold out just one more night. I know we’ve been without sleep a long time. But we expect another attack from them tonight and they may come through here. I have every reason to believe that we will have reliefs here for all of us in the morning.”

The following night, perhaps the most stirring defensive stand in the history of the Marine Corps took place along the high ground that has since been known as either “Bloody Ridge” or “Edson’s Ridge” in honor of the gallant officer who seemed to be everywhere during the battle that saved Henderson Field, the American perimeter, and possibly the entire Allied initiative in the Pacific War.

Edson’s men braced themselves, and the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines came up to reinforce the network of foxholes and machine-gun nests. The Japanese came on in waves, overlapping forward Marine positions and engaging in close-quarter combat. Captain William J. McKennan remembered, “The Japanese attack was almost constant, like a rain that subsides for a moment and then pours the harder …. When one wave was mowed down—and I mean mowed down—another followed it into death.”

Three companies of Japanese infantry managed to skirt the Marine line and reached the edge of Henderson Field, but it was their high-water mark. A swift counterattack by Marine engineers threw them into retreat. Attacks lasted until approximately 4 a.m. on September 14, when two Japanese infantry companies struck the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines near the beach and were hurled back with great loss.

Throughout the savage fight for Bloody Ridge, Marine artillery was superb. “The 11th Marines’ 105mm howitzers gave good account of themselves in the battle, with the heaviest concentration of artillery fire Guadalcanal had seen so far,” recalled one veteran of the action, “dropping well-placed barrages into enemy positions just 200 yards from the dug-in Marines. When it was over, the Marines’ 105 howitzers had fired 1,992 rounds into the enemy’s ranks. The 75s alone had unloaded more than 1,000.”

A forward-observation post was maintained on top of the ridge, and the range to Japanese targets closed at times to a mere 1,600 yards. “The way it fell,” said one observer, “it looked as if the artillery lads were trying to burn out their barrels, so fast and furiously did the shells go over the Raiders. Out of this barrage grew an apocryphal story: a Jap officer is supposed to have asked later, upon his capture, to see the ‘automatic artillery’ we used that night.”

More than 800 Japanese soldiers were killed and 600 wounded before the ferocious Marine defenders of Bloody Ridge broke the back of their repeated charges. The Marines lost 59 dead and nearly 200 wounded. Captain Kenneth Bailey of Company C, 1st Raider Battalion received the Medal of Honor for conspicuous bravery. Suffering from a serious head wound, the company commander rallied his men during 10 hours of on-again, off-again hand-to-hand fighting. Bailey survived the hellish night but was killed in action at the Matanikau River two weeks later. For his courage under fire and outstanding leadership, Edson also received the Medal of Honor.

Costly though it was, the victory at Bloody Ridge bolstered Marine morale and electrified the American public. The Marine Corps was fast earning its reputation as one of the world’s premiere land-combat forces.

Vandegrift had no time to revel in the newly found fame. While scores of sick and wounded Marines were evacuated, reinforcements came ashore. By late September, the Marines on Guadalcanal were up to division strength, more than 19,000. However, the reinforcements did not reach the island without a price. On November 15, the aircraft carrier Wasp was sunk by a Japanese submarine, and the same torpedo spread damaged the battleship North Carolina and a destroyer.

As their casualties mounted and airstrikes from Henderson Field sank several transport craft loaded with combat troops, the Japanese realized that the outcome of the battle for Guadalcanal would be critical to the course of the war. At least two divisions of Japanese troops were detailed to the island for a decisive encounter.

Vandegrift expanded his defensive perimeter toward the Matanikau River in the direction of the Japanese landing beaches. The 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, under the command of Lt. Col. Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller and supported by the 5th Marines, now under Edson’s leadership, conducted a reconnaissance in force near the heights of Mount Austen and beyond the Matanikau and encountered stiff resistance. It was apparent that any Marine move westward on Guadalcanal would be hotly contested.

Although he knew the fighting would be rough, Vandegrift maintained an offensive initiative and sent forward another strike at the Japanese along the Matanikau. This advance was undertaken by five infantry battalions, and the tip of the spear was the Whaling Group, a force of riflemen who were familiar with jungle fighting and highly trained as scouts and snipers, led by Lt. Col. William “Wild Bill” Whaling. Commanding his own men and the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines, Whaling plunged into the jungle to blaze the trail for the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 7th Marines, who would arc toward the coast, and Edson’s 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 5th Marines, which would attack directly across the river mouth.

Japanese troops from the 4th Infantry Regiment had ventured across the Matanikau to establish artillery firing positions. They offered stiff resistance to the Marine advance, but a reinforcing Raider company hit their flank, and in the ensuing near-encirclement the Japanese were routed. As Whaling wheeled toward the coastline on October 9, Puller’s 7th Marines caught a concentration of enemy troops in a ravine and decimated them with small-arms and mortar fire. Eventually, Whaling and Puller circled back toward Edson, and the combined Marine force cleared the mouth of the Matanikau. The action disrupted the Japanese timetable for their own offensive and cost them 700 dead and wounded against 65 Marines killed and 125 wounded.

General Hyakutake finally made landfall on Guadalcanal on October 7, just as the Whaling operation was getting started. Undeterred, he supervised the landing of more Japanese troops of the Sendai Division under Major General Masao Maruyama. The Japanese Navy offered support in a coordinated effort to bombard Henderson Field, continue reinforcement and resupply for the troops ashore, and draw the Cactus Air Force into battle, where Japanese planes would hopefully annihilate the Americans.

Four days after Hyukatake’s arrival, a heavily escorted run of the Tokyo Express met U.S. Navy cruisers under Rear Admiral Norman Scott. Both sides suffered heavily during the nocturnal Battle of Cape Esperance, but the Japanese were able to land additional reinforcements. On October 13, the Japanese battleships Kongo and Haruna blasted Henderson Field, and the following day more than 4,500 Japanese troops were landed on Guadalcanal while Hyakutake prepared a major push against Henderson Field.

On October 13, just in time to endure the bombardment from the Japanese battleships, the Army’s 164th Infantry Regiment of the 23rd Division, popularly known as the Americal Division, came ashore. The Army troops were a federalized National Guard outfit, and they brought with them one of the true war-winning weapons of the global conflict, the M-1 Garand rifle, a dependable semiautomatic weapon that was capable of a considerably higher sustained rate of fire than the bolt-action Springfield that the Marines used. Perhaps as fiery and pugnacious as the M-1, Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey took command of the Guadalcanal campaign, replacing Ghormley on October 18.

Hyakutake approved Maruyama’s plan to move the bulk of nearly 7,000 Japanese troops along an arduous jungle trail and across two rivers, the Matanikau and the Lunga, to attack the Marine perimeter from the south near the site of Edson’s heroic stand nearly six weeks earlier. The long march sapped the soldiers’ strength, but the order to attack soon came anyway. On October 20, the Japanese probed near the mouth of the Matanikau as Murayama’s force advanced.

Three days later, nine Japanese tanks crossed the river. Immediately, the 37mm anti-tank weapons of Lt. Col. William N. McKelvy, Jr.’s, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines swung into action, destroying eight of them. A single tank got across the river, and an intrepid Marine blew one of its treads off. A halftrack rolled up and blasted the stationary target with its 75mm gun. Once again, accurate artillery fire riddled the Japanese troop concentrations.

As Maruyama crept closer to his jumping-off positions, the 7th Marines held 2,500 yards of frontage from Lunga to Edson’s Ridge, where they met the untested 164th Regiment, under Lt. Col. Robert K. Hall, which held 6,600 yards of terrain eastward from the base of the high ground. The action near the seacoast prompted Vandegrift to shift the 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines east to a 4,000-yard gap in the defensive perimeter. The redeployment was fortuitous, placing the battalion squarely in front of one designated axis of the Japanese advance.

After daylight on October 24, a Japanese officer was seen observing the Marine perimeter through binoculars. A short time later, scout snipers sent forward to reconnoiter reported smoke from fires rising roughly two miles south of Lt. Col. Puller’s positions. Six battalions of the Sendai Division waited for darkness and then stepped off in the rain just before midnight, slipping around a reinforced Marine outpost that warned Puller that the enemy attack was underway.

In short order, Puller received another phone call. A company in the line reported that the Japanese were cutting through the barbed wire entanglements to its front. Puller called in the men from the outpost, 46 Marines of the 1st Battalion under Sergeant Ralph Briggs, telling them to move to the left and keep moving into the Marine line.

“Don’t fail, and don’t go in any other direction,” Puller admonished. “I’ll hold my fire as long as I can.”

Curiously, some of the Japanese junior officers began to stand up, offering targets for Marine rifles. Moments later, Puller passed the word to commence firing. The Marine perimeter lit up with a hail of bullets, and mortar shells whooshed from their tubes. One of the early heroes of the fight was Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone, a veteran of the Army who was familiar with the .30-caliber Browning machine gun and now as a Marine commanded two sections of the water-cooled weapons.

Basilone was a proficient killing machine during the nocturnal brawl, and enemy dead piled up in front of his position, obscuring his line of fire until the bodies were cleared during a lull in the fighting. When he was able, Basilone went to the rear for ammunition and parts to keep his machine guns firing. After the Japanese renewed their attacks, he was still fighting hours later, firing his pistol at the enemy. He received the Medal of Honor during a ceremony in Australia in May 1943 along with 2nd Lt. Mitchell Paige, who also commanded a machine-gun section during the battle.

Counterattacks eliminated a wedge the Japanese had driven into the line, but Puller was hard-pressed and called for artillery fire from the reliable and accurate guns of the 11th Marines.

He also sent for the 3rd Battalion, 164th Infantry Regiment. Puller met Hall and tersely informed him, “I don’t know who’s senior to who right now, and I don’t give a damn. I’ll be in command until daylight at least because I know what’s going on here, and you don’t.”

Hall readily agreed, responding, “I understand you. Let’s go.”

The two officers walked Puller’s perimeter, feeding the Army troops into positions with Marines. The inexperienced soldiers of the 164th would soon become battle-hardened beside the Marines. Repeated Japanese attacks rolled in, but the machine guns and 37mm guns of the 7th Marines Weapons Company sliced into their flanks.

As the sun rose, Japanese bombers attacked the Marine positions while their artillery pounded the defensive line and a pair of destroyers fired a few rounds before 5-inch Marine shore batteries drove them away. The muddy runway at Henderson Field dried out sufficiently for the Cactus Air Force to rise into the air, promptly shooting down 22 enemy planes for the loss of three of their own.

As daylight faded on October 25, Murayama sent his depleted troops forward again. This time, the results were predictable. The 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines under Lt. Col. Herman Hanneken withstood three charges from the remnants of the Sendai Division. The battalion executive officer, Major Odell M. Conoley, led a counterattack that patched a breach in the line.

Finally, Maruyama was spent. He had lost more than 3,500 men and gained nothing. Combined losses among the Marines and Army troops amounted to 300 killed and wounded. General Vandegrift commended the 3rd Battalion, 164th Infantry, saying his “division was proud to have serving with it another unit which had stood the test of battle.”

Puller was less effusive. In his own way, he praised the Army troops, “They’re almost as good as Marines.”

While the combined Marine Corps and Army defense pushed the Japanese back from Henderson Field with heavy casualties, the struggle for naval supremacy continued. On October 26, U.S. and Japanese carrier forces clashed in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. The carrier Hornet was sunk, and the Enterprise was badly damaged. Three Japanese carriers were damaged, and more than 100 of their planes were shot down. With the failure of Murayama’s land offensive, the Japanese fleet pulled back as well.

Vandegrift seized the moment and marshaled reinforcements. With assurances of continuing support from the highest echelons of Marine Corps command and even the endorsement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the American commitment to win at Guadalcanal was firm. In early November, Marine squadrons VMSB-132 and VMF-211 joined the Cactus Air Force at Henderson Field, and the aircraft of MAG 11 were relocated to Espiritu Santo, a base closer to Guadalcanal. Another 4,000 troops came ashore with the commitment of the 8th Marine Regiment from New Caledonia and the artillery of the 1st Battalion, 10th Marines. In time, the remaining elements of the Americal Division, additional units of the 2nd Marine Division, and the Army’s 25th Infantry Division would enter the battle.

In November, the Marines continued clearing Japanese resistance west of the Matanikau River and expanded their defensive perimeter. The Japanese were still full of fight and sent a regiment of the 38th Infantry Division to Guadalcanal to mount a two-pronged offensive against the American flanks. Both forays were beaten back with serious losses. At mid-month, one Japanese reinforcement effort was turned back during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, while a second succeeded in landing some troops. During four days of fighting, both sides took severe punishment. American planes sank seven Japanese troop transports, killing many enemy soldiers while Imperial Navy destroyers rescued 5,000 from the water.

Only about 3,000 additional Japanese soldiers reached the island during the lengthy naval battle, but including other recent Tokyo Express missions, up to 10,000 soldiers of the 38th Division managed to land. Even so, the cost was becoming too steep for the Japanese. The Tokyo Express had run its course, and this marginally successful operation marked the last large-scale Japanese reinforcement effort. By late November, it was apparent that ongoing resupply would tax their resources beyond capacity. Losses in ships and supplies could not readily be replaced. Starvation, disease, and the strengthening enemy relentlessly stalked the Japanese soldiers already ashore.

November proved to be the month of decision at Guadalcanal. The 1st Marine Division and attached units had held the line, sometimes just barely, and the Cactus Air Force had kept the Japanese at bay in the skies above the southern Solomons. In time, both were strengthened and began to assert supremacy. While the Japanese effort to wrest control of the island had begun the long, downward spiral toward failure, American losses could be replaced.

After four months of fighting on the fetid island, ravaged by disease, with more than 3,000 cases of malaria and dog-tired, the 1st Marine Division was withdrawn from Guadalcanal in early December. In its place came the 132nd Infantry, the last regiment of the Americal Division, followed by the 6th Marine Regiment, which joined the other three regiments of the 2nd Marine Division, the 2nd, 8th, and 10th, already on Guadalcanal, and the Army’s 25th Infantry Division.

Under extremely adverse conditions, Vandegrift had performed admirably. Army Major General Alexander M. Patch subsequently relieved him of command on Guadalcanal, and Vandegrift received both the Navy Cross and the Medal of Honor for his sterling service. Patch’s command, 50,000 strong, was designated the XIV Corps.

A new fighter strip was built at Henderson Field, and the aircraft of the 1st and 2nd Marine Air Wings were rapidly strengthened while three new Army fighter squadrons and a bomber squadron arrived. American air power made any Japanese transit of The Slot during daylight hours virtually impossible.

In late December, Patch gave the order to mount the largest American offensive of the campaign to “attack and destroy the Japanese forces remaining on Guadalcanal.” Combined Army and Marine advances isolated the Japanese troops dug in on Mount Austen and adjacent high ground that threatened any further movement westward. Japanese troops of the 38th Division and the remnants of the Sendai Division put up stiff resistance, but the Army’s 27th and 35th Infantry Regiments drove west with the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines advancing on their left flank. The 8th, 2nd, and 6th Marines were heavily engaged.

Captain Henry P. “Jim” Crowe of the 8th Marines, who later distinguished himself during the fight for Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands, exhorted his men with, “You’ll never get a Purple Heart hiding in a foxhole! Follow me!”

Components of the Americal Division and the 2nd Marine Division were formed into the CAM Division (Combined Army Marine), and progress was steady as the 25th Infantry Division joined in the fight and American forces converged on Cape Esperance from two directions. By late January, resistance was waning and disorganized. The ground gained sometimes exceeded 2,000 yards per day.

The reason for the more rapid advance was not clear at first. Patch had been warned of increasing Japanese movement of men and ships and initially believed that the enemy intended to renew its offensive effort. Actually, by the middle of December the Japanese had grudgingly acknowledged that Guadalcanal should be conceded to the Americans. About 11,000 Japanese soldiers, many of them emaciated and thoroughly weakened by starvation and disease, were withdrawn from the island during the first week of February 1943.

On the 9th, American forces converging from the east and west linked up at Cape Esperance. The fight for Guadalcanal was over.

The victory had been at a terrible cost, and the Marines had borne the brunt of the casualties. Nearly 1,600 U.S. personnel had died, and more than 1,150 were Marines. Of the 4,709 wounded, 2,799 were Marines. The Marine pilots of the Cactus Air Force suffered 147 dead and 127 wounded.

In turn, the Japanese lost 25,000 men killed and wounded, many of them from elite formations that would never again take the field as cohesive units.

Guadalcanal was the crossroads to victory for the United States in the Pacific War, and the Marine Corps blazed the trail. Many bloody days of fighting remained, but the Americans were now firmly on the offensive in the Pacific.

Among the high-ranking Japanese officers who understood the gravity of the defeat, Kawaguchi of the 35th Infantry Brigade concluded, “Guadalcanal is no longer merely a name of an island in Japanese military history. It is the name of the graveyard of the Japanese Army.”

Michael E. Haskew is the editor of WWII History magazine and the author of many books and articles on military subjects. He resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments