By John W. Osborn, Jr.

It was a quiet dinner on a side street in Berlin the evening of June 26, 1939, but more than food would be devoured that night.

The locale was one of Berlin’s less-esteemed eating establishments, long used by German Foreign Office officials for the discretion it offered. At dinner were Dr. Kurt Schnurre and Walter Schmid of the German Foreign Ministry and Soviet diplomats Georgi A. Astakhov and Evgeny Babarin.

With Europe ruinously rushing toward war, they had been mundanely and tediously crunching the numbers of a trade agreement. Hitler’s threatening Poland versus Great Britain and France’s guaranteeing of Polish independence had set off a frenzy of diplomatic activity that in the end became centered on the power that had before been kept out of international relations, treated on all sides as an odious outcast—the Soviet Union.

“We formed the opinion,” Soviet Premier Josef Stalin was to tell Prime Minister Winston Churchill in the Kremlin in 1942, “that the British and French governments were not resolved to go to war if Poland were attacked, but they hoped the diplomatic line-up of Great Britain, France, and Russia would deter Hitler. We were sure it would not.” Stalin had signaled to Hitler this shift in the diplomatic winds with a speech in March 1939, blasting the British and French for not standing up to the Nazi dictator at Munich, warning them the Soviets would not be expected to “pick their chestnuts out of the fire.” Two months later, Stalin fired the main proponent of an alliance with Britain and France, Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov.

Over a mediocre meal of salmon and Rhine wines, talk deliberately drifted on the German side from economics to elsewhere. “There was no problem,” Schnurre, on intentional instructions from Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, carefully commented, “between the two countries anywhere from the Baltic to the Black Sea, and to the Far East, which could not be solved. No problem at all.”

That calculated comment set in motion events leading to one of history’s great diplomatic deceits—the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, signed in Moscow two months later. Behind this public show of nonaggression between Nazi Germany and Communist Russia was a secretly planned invasion by both against the country between them, Poland.

Stalin gave the West a last-gasp chance for an alliance, but the British and French sent a low-ranking military mission to Russia with no authorization to sign anything, while Hitler secretly struggled with the Soviets over a proposed 25-year non-aggression pact. “It was considered necessary by Stalin and Molotov for bargaining purposes to conceal their true intentions till the last possible moment,” Churchill conceded about their diplomatic duplicity. Hitler, frustrated, finally outmaneuvered the Western Allies, directly cabling Stalin and requesting him to receive Ribbentrop to sign a deal on the spot.

The public pact to “desist from any act of violence, any aggressive action, and any attack on each other” shocked the world. A protocol that followed was kept secret. Uncovered in 1945 by a U.S. State Department investigator going through German diplomatic archives evacuated from Berlin, the protocol was only admitted to by the Soviets in 1989. It deviously declared, “In the event of territorial and political arrangement of the areas belonging to the Polish State, the spheres of influence of Germany and the U.S.S.R. shall be bounded by the line of the of the Narew, Vistula, and San Rivers. The question of whether the interests of both parties make desirable the maintenance of an independent Polish state and how such a state should be bounded can only be further determined in the course of further political developments. In any event both Governments will resolve this question by means of friendly agreement.”

The diplomatic double-talk disguised the deliberate destruction of Poland as an independent nation. For the Soviets, it was about recovering territories of Byelorussia and the Ukraine lost from the 1920-1921 war with Poland. For Stalin, there was a personal score to settle: He was the commissar of that war, and he and the military commander bitterly blamed one another for the defeat. Stalin would win the argument, having his opponent beaten and summarily shot.

Hitler and the Wehrmacht began to territorially and politically “arrange” the dismemberment of Poland a week later. Through the German ambassador to the Soviet Union, Ribbentrop queried Stalin’s stone-faced stooge Foreign Minister Vyachslev Molotov, “Would the U.S.S.R. object if, to hasten the destruction of the Polish Army, the Wehrmacht were to conduct operations in the Soviet sphere of influence? Would the U.S.S.R. not consider it desirable to send Russian forces in good time into the zone of influence defined for the U.S.S.R. in Polish territory?”

Molotov answered the next day, “We agree with you that at a suitable time it will be absolutely necessary for concrete action. We are of the view, however, that this time has not yet come.” As they would do again in 1944 by waiting outside Warsaw, the Russians were letting the Germans do the work of destroying Polish resistance for them to the extent possible.

On September 8, Ribbentrop anxiously asked again for Soviet military intervention, saying the Polish Army was “more or less in a state of dissolution.” Molotov told the German ambassador the Red Army would move “within the next few days,” and the Russians spent them mobilizing along Poland’s western border and trying to find a rationale for invading a country it had signed its own nonaggression pact with in 1932, still set to run until 1945.

Molotov finally came up with a rationale, asserting, “The Soviet Government intended to take the occasion of the further advance of German troops to declare that Poland was falling apart and that it was necessary, in consequence, to come to the aid of the Ukrainians and White Russians, make the intervention of the Soviet Union plausible to the masses and at the same time avoid giving the Soviet Union the appearance of an aggressor.”

A propaganda piece ran in Pravda on September 14. German forces had crossed the demarcation line noted in the pact, and the Germans’ premature announcement of Warsaw’s fall put pressure on Stalin to act. “Now it was the turn of the Soviets,” Churchill was to write. The German ambassador in Moscow had reported on September 16, “I saw Molotov at 6 pm Molotov declared that military intervention by the Soviet Union was imminent—perhaps even tomorrow or the day after.” Just 12 hours later, at 5:20 am, September 17, 1939, Molotov was secretly sending Berlin the word that the Soviet invasion of Poland was imminent.

First, the formalities of the aggression had to be odiously observed. Polish Ambassador Waclaw Grzybowski met with Soviet Deputy Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Vladimir Potemkin, to receive an official note. With Gryzbowski insisting to first know what was in it, Potemkin dismissively droned Poland’s declaration of double doom:

“The Polish-German war has revealed the internal bankruptcy of the Polish state.

“During the course of ten days of military operations, Poland has lost all her industrial areas and cultural centers. Warsaw no longer exists as the capital of Poland. The Polish government has disintegrated and no longer shows any signs of life. This means that the Polish state and its government have in fact ceased to exist. Therefore, any agreements concluded between the U.S.S.R. and Poland have lost their validity.

“Left to fend for herself and bereft of leadership, Poland has become a convenient field for all kinds of hazards and contingencies which may constitute a threat to the U.S.S.R. For these reasons, the U.S.S.R., which has hitherto remained neutral, can no longer adopt a neutral attitude toward these facts.

“The Soviet government can furthermore not be indifferent to the fact of its kindred Ukrainian and Belorussian people, who live on Polish territory and who have been left to the mercy of fate, have been left defenseless.

“In view of this situation, the Soviet government has directed the High Command of the Red Army to give the order to its troops to cross the Polish frontier and take under the protection the life and property of Western Ukraine and Western Byelorussia.

“At the same time the Soviet government intends to take all measures to extricate the Polish people from the unfortunate war into which they have been dragged by their unwise leaders, and to enable them to live a peaceful life.”

Grzybowski angrily flung the note back on the table and responded, “Poland will never cease to exist!” A 10-minute table tussle followed as the note was pushed back and forth.

Grzybowski finally stormed out, only to find the note at his embassy’s doorstep in a messenger’s hand. He sent the messenger away but found the note again in his mail the next day, delivered by regular post. Claiming that Grzybowski’s diplomatic immunity disappeared with his country, the Soviets arrested the Polish diplomat. However, the German ambassador, an aged aristocrat who still had a sense of shame, got him released. The consul in Kiev was less fortunate, arrested and never heard from again. The Soviets then delivered the message militarily.

The Soviet invasion began 20 minutes sooner than Stalin had expected. “Dead silence fell,” a Polish general remembered. The commander of one unit, a soldier recalled, announced the invasion and then “declared the situation hopeless without any chance of victory, and so allowed the men to lay down their arms.” He then asked those who “chose to fight for the honor of the Polish Army to step to the right. The entire platoon stepped to the right.”

A half-million Soviet troops invaded with almost 5,000 armored vehicles and 2,000 aircraft. Pathetic Polish confusion was typified by a border officer on the phone to general staff headquarters being asked to send an emissary to the Russians to find their intentions.

The border officer’s response was terse. “All my battalions are fighting and two Soviet tanks have been destroyed. I doubt whether I will be able to fulfill the order regarding the envoy. Air raid. I must go.”

Compared to the Wehrmacht, the Red Army looked more like a military mob. “This was Asia. Asia has invaded us,” a Polish officer said. “The soldiers looked tired, their coats were torn. They were dirty and harsh looking,” a Polish girl said of the Soviet soldiers entering her town. “They wanted to buy any kind of watch, as long as it ticked.”

Soviet forces advanced along almost 900 miles in two fronts (army groups) around the Pripet Marshes: the Byelorussian in the north led by General Michael Kovalev, the Ukrainian in the south under General Semyon Timoshenko. Accompanying Timoshenko as commissar was Stalin’s hack/hatchet man in the Ukraine, Nikita Khrushchev. His wife, Nina, accompanied Khruskchev, searching for her parents, who had been stranded in Poland after the end of the war in 1921.

Kovalev aimed for Vilna and Grodno; Timoshenko drove toward Lvov. “Germany having killed the prey, Soviet Russia will seize that part of the carcass that Germany cannot use. It will play the ignoble role of hyena to the German lion,” excoriatingly editorialized the New York Times. The Soviets lost more armor and aircraft to accidents and mechanical breakdown than to combat action. Fortunately for them, the only forces they faced were the 12,000-man Border Protection Corps (KOP) and scattered, disorganized Polish troops fleeing from the Germans.

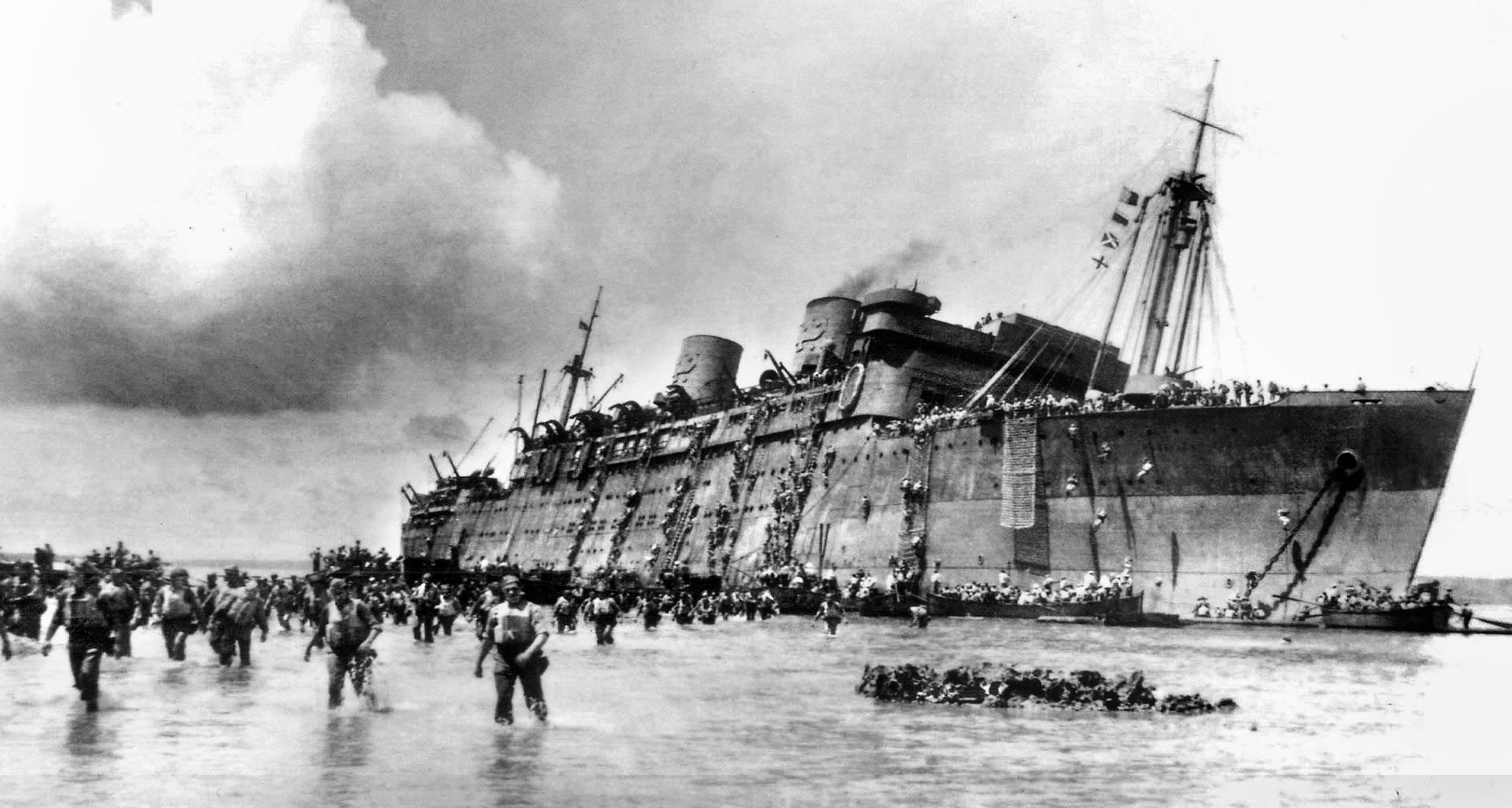

The Soviet invasion made the Poles give up what hope they had of resisting the Germans, and the government and high command fled. By just 4:00 pm that same day, the Polish commander-in-chief was informing his shattered army, “I hereby order a total withdrawal to Romania and Hungary via the shortest possible route. Do not fight the Bolsheviks unless they attack or attempt to disarm our forces.” But some Polish troops could not, or would not, obey. One KOP unit of just 50 men held off an entire Soviet division for four days until incinerated in their bunkers by flamethrowers. Another unit killed 200 Soviet soldiers, while a third saw fully half of its own men fall fighting.

At times, the Soviets deliberately confused the Poles by approaching while waving white flags and with bands playing patriotic Polish music. Their commanders shouted deceptively,” Don’t shoot, we’ve come to help you against the Germans.” Many Soviet soldiers thought that was what they were doing, expressing confusion on learning differently. Some Polish officers believed the ruse. Invited to a reception, they were disarmed in their dress uniforms at gunpoint.

Other Soviets did not bother to fabricate fraternal fellowship. One Pole watched armor rampage through the streets. “They shot at everything that moved. The panic was indescribable, people ran in all directions, unable to find time or place to hide. I stood aghast as one small boy, frightened and confused, stopped to stare at an approaching tank. They simply machine-gunned him down.”

The defenders of Vilna and Grodno in the north resisted heroically. Vilna had just 7,000 regular Polish troops, with only 15 artillery pieces and a few dozen machine guns. “The tanks were followed by infantry,” a Polish soldier in the 6th Legion’s Infantry Regiment remembered. “They cried ‘Hurrah! For Stalin! For the Motherland! Hurrah! I will never forget those cries. But we took them with flanking fire.”

“One falls, another comes after him, is hit, and another comes,” one Polish defender said of oncoming Red Army soldiers. “A whole heap of corpses grew—and not a small one. We fought until evening, and I saw tanks catch fire one after another, our men throwing bottles with gasoline.” After 24 furious hours on September 19, the Poles fought their way 12 miles to safety in Lithuania. The Poles at Grodno, 75 miles southwest, had even fewer resources—2,000 regular troops, civilian volunteers, a dozen machine guns, and a pair of antiaircraft guns—but no less battled bitterly.

Soviet tanks rolling on the morning of September 20 were hit by antiaircraft fire aimed at their tracks, then set ablaze with what the world would later come to know as Molotov cocktails, gasoline in bottles. Savage street fighting took place. A schoolteacher watched the struggle and later wrote of the Polish soldiers, “They fought as long as they have ammunition in their rucksacks, as long as grenades hang at their belts, as long as the machine guns they had pulled up to the barricade spit bullets.”

Boy scouts acting as messengers and ammunition runners caught by the Soviets were tied as human shields to their tanks. Resistance in Grodno was crushed the next day. By then, an encounter of a Soviet armored car with elements of the German 10th Panzer Division just north of Brest-Litovsk set the stage for the signature scenes of the Soviet invasion of Poland. The irony was not lost on Churchill. “Here,” he wrote, “in the previous war the Bolsheviks in breach of their solemn obligations with the Western Allies, had made their separate peace with the Kaiser’s Germany, and had bowed to its harsh terms. Now in Brest-Litovsk, it was with Hitler’s Germany that the Russian Communists grinned and shook hands.”

Doing the handshaking for Hitler—and unhappy about it—was General Heinz Guderian. He had fought two days to take Brest-Litovsk from the Poles only to learn from the secret protocol that he had to hand it over to the Soviets. He no doubt got some satisfaction when he reviewed ragged Red Army troops at the September 22 handover ceremony while standing on a quickly raised platform and compared them to his own men, with sharp uniforms and abundant, modern equipment. The event was also attended by Red Army Brigadier General Semyon Krivoshein, an interestingly low-level officer for such an event.

In the meantime, on the southern, Ukrainian front Timoshekno ordered his command to reach the Kowel-Wlodzimierez-Wolynski-Sokol Line in three days, then advance up the San River. Soviet forces had no trouble meeting his deadline, advancing 60 miles the first day. “When we crossed the border we encountered no resistance,” Khrushchev was to recall. “Our troops reached Ternopol very quickly. Timoshenko and I traveled through the city and returned there by a different road, which was not very intelligent after all because some Polish units were still active, and they could have detained us. He and I traveled through small settlements inhabited by Ukrainians and through bigger towns with a fairly large Polish element; moreover, we were in areas where no Soviet troops were yet present, so anything could have happened. As soon as we returned to our own forces we were told that Stalin was asking for us on the phone. We reported back on how the operation was going.”

Unaware how millions of their countrymen had been systematically starved by Stalin during the 1930s, Ukrainians greeted the Soviets. “Women and girls began handing out flowers,” a Red Army general recalled. “Initially sparsely, but then more and more frequently, people began cheering. As we went down the street, we were welcomed by ‘Long Live the Red Army!’ and ‘Long Live the Soviet Union!’ shouted from every direction.” They more cruelly celebrated the slaughtering of local Poles.

When the Soviets reached the outskirts of Lvov on September 21, already under German attack, a Polish colonel was sent to meet them. He asked, “Why have you come?”

“You must have read the newspapers,” his Soviet counterpart replied.

When the Pole responded that newspapers were not getting through, the Soviet officer said, “So maybe you’ve heard on the radio what has taken place?”

The Pole knew but claimed the Germans had cut the power to the city and radios were dead. He asked again, “So why are you here?”

The Soviet officer repeated the lie that they were there to fight the Germans. The Pole pretended to believe him and showed him German positions on a map. The Soviet officer insisted, “But we wish to enter the city,” suggesting they needed “observation points” for artillery.

“Something odd is taking place,” the Pole would reflect. “But one thing is certain, both enemies want to break into the city.”

After consulting his officers and deciding resistance from both sides was suicidal, the Polish commander in Lvov surrendered to Timoshenko and Khrushchev at 3:00 pm the next day. Nina Khrushchev was also successful at finally finding her parents. Khrushchev’s relief at the reunion was matched by his anger at her packing a pistol.

Khrushchev assured surrendering Polish officers that they would be treated properly, advising, “Russia always kept her obligations.” Poles learned soon enough, however, that these words were worthless. Polish General Wladyslaw Anders was encircled with his forces by Soviet armor just 12 miles from refuge in Romania and after fierce fighting forced to surrender. In the future for Anders were rat and bedbug-infested cells, beatings, interrogations, dysentery, scurvy, and finally solitary confinement cell in the Lubyanka—and he would be among the lucky ones!

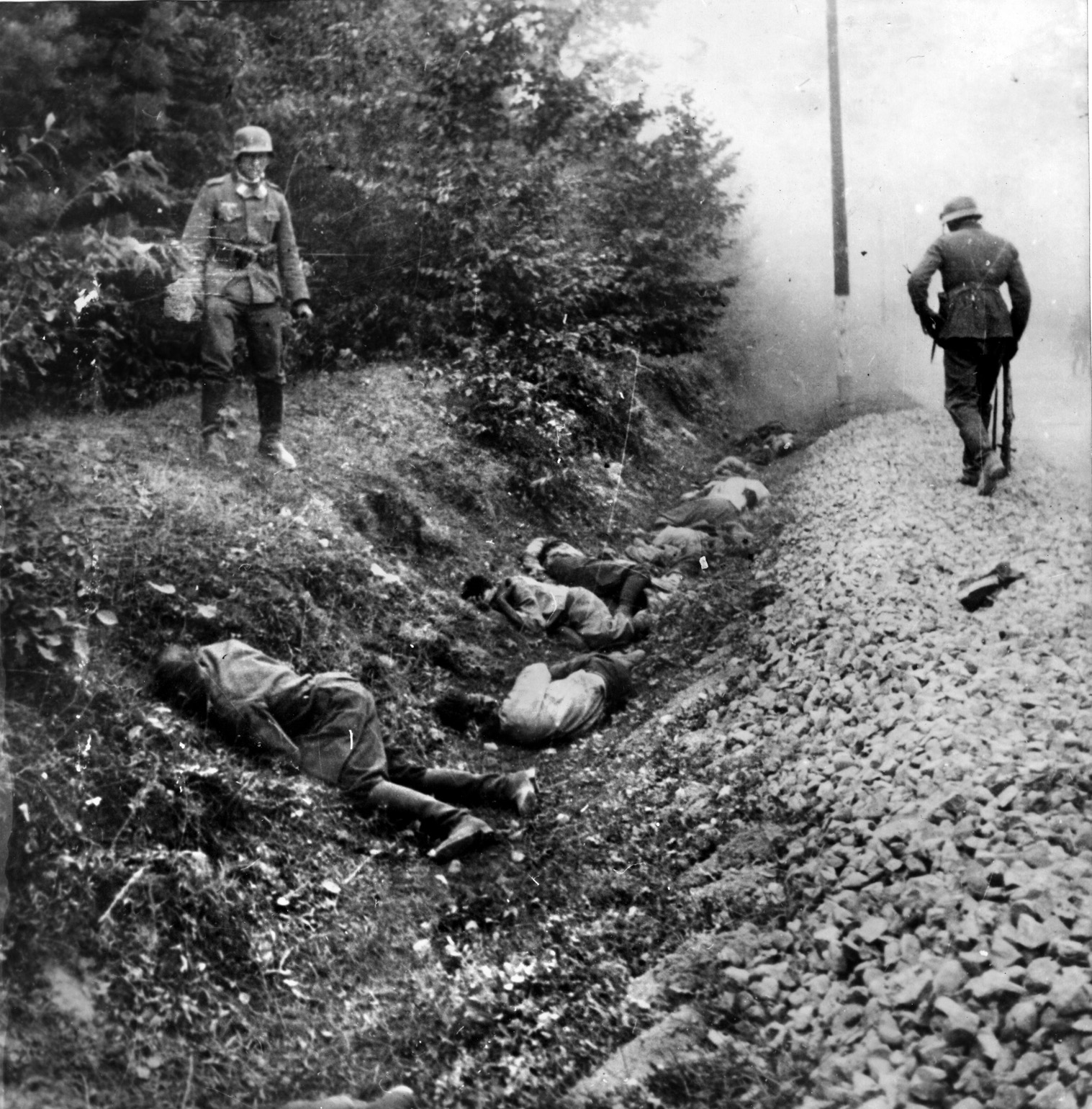

After the surrender of Grodno, 29 Polish officers were marched out of town to be shot on the spot; their commander, Brigadier General Jozef Olsyna-Wilczynski, seized while fleeing by car, was summarily shot by the side of the road. The Soviets were, to their mind, displaying courtesy to his widow by giving her his blood-stained briefcase. A surrendering Polish brigade had its 100 officers and NCOs separated. They were marched away, and soon the soldiers of their former command heard shooting. “We asked the Soviet officers if another Polish detachment was still fighting,” one soldier remembered. “In response we were told, ‘Those are your masters, shot dead.’”

Some 2,000 Polish soldiers were captured 90 miles south of Lublin. The Polish 7th, 39th, and 41st Regiments were surrounded and surrendered the next day. Some 1,500 Polish cavalry charged Soviet tanks trying to break out of encirclement; 140 were killed, and the rest surrendered. The Poles under General Wilhelm Orlick-Ruckemann won their only victory against the Soviets at the village of Szack on September 28 against the Soviet 52nd Rifle Division, destroying eight T-26 tanks with Bofors anti-tank guns while 300 Soviet soldiers were killed in hand-to-hand fighting.

Those Poles, down to only 3,000 men, moved 18 miles west of the Bug River. Two days later, they fought the Soviets again at the battle of Wtytczno. After eight hours of hard fighting, they were down to 60 artillery shells, and the troops were too exhausted to carry out a counterattack Orlick-Ruckemann had ordered. That night, believing that his command would be wiped out the next day, Orlick-Ruckemnn ordered his troops to break out and disperse. He got through to Lithuania, but his wounded were not so fortunate. They were left behind, and the Soviets dreadfully dumped them into the local town hall to bleed to death.

Ribbentrop completed the cynical carving up of Poland by suggesting a demarcation line delineated on a map. Stalin answered by signing his name to it in blue crayon, 10 inches long and 18 inches wide. “Is my signature clear enough for you?” he asked. Ribbentrop responded that Germans and Russians should never fight again. Stalin pondered, then answered simply, “This ought to be the case.”

The last Polish units held out against the Soviets until early October. “Russia has pursued a cold policy of self-interest,” Churchill commented at the time. The quick campaign had cost the Soviets 737 killed and 1,862 wounded, and for it in the division of Poland they got 72,780 square miles to the Germans’ 77,600. The Soviets claimed tremendous Polish plunder—900 artillery pieces with a million shells, 10,000 machine guns, 300,000 rifles with 150 million rounds, and 300 aircraft.

Polish combat casualties were initially estimated at 18,000, but they were to climb horrifyingly higher. “There will never be another Poland,” the Soviet officer driving General Wladyslaw Anders to his cruel captivity told him.

The Soviets specifically slaughtered 50,000 members of Polish society—landowners, teachers, doctors, priests, businessmen, lawyers, and others. They economically eviscerated their piece of Poland with agriculture cruelly collectivized and over 400 banks and over 1,000 credit institutions looted. An estimated 1,500,000 people, including Poles, Jews, Ukrainians and Byelorussians, were packed into freight cars without food, water, or heat. “The nights were made unbearable not only by the racket of the trains themselves but the piteous cries of adults and children begging to be let out,” remembered a villager along those terrible train tracks remembered. Thousands died en route to labor camps, while many more were worked, starved or frozen to death.

Some 250,000 Polish soldiers fell into Soviet hands. “What are they doing now? Where are they? How many of them are still alive?” a Polish colonel who had made it to the West was asking in 1941. Half of them were never heard from again. Some 15,000 officers, including a dozen generals and an admiral, were among those missing without a trace. General Anders, released to organize a free Polish Army, confronted Stalin in the Kremlin about the missing on December 3, 1941.

“That’s impossible. They must have escaped,” Stalin replied. When Anders asked where possibly to, Stalin shrugged, “Well, to Manchuria.” The fate of at least 4,134 became known in 1943 with the discovery of their buried bodies in the Katyn Forest, executed with a bullet in back of each head. Not until 1990 did the Russians admit to the Katyn Forest massacre.

Ribbentrop had told Stalin the nonaggression pact and protocol were “the foundation stone of the new friendly relations between Germany and the Soviet Union.” But Churchill would say, “I was still convinced of the profound, and as I believed quenchless, antagonism between Russia and Germany, and I clung to the hope that the Soviets would be drawn to our side by the force of events.” That “force of events” would come two years later when Hitler tore up both pact and protocol to invade the Soviet Union.

“The very fact of the conclusion of an alliance with Russia embodies a plan for the next war. Its outcome would be the end of Germany,” Hitler had written years earlier in Mein Kampf.

Poland did not free itself from Soviet domination until 1989.

Author John W. Osborn, Jr., is resident of Laguna Niguel, California. He has written for WWII History on a variety of topics.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments