A few weeks ago, I was able to take a long-delayed summer vacation, this time to New England, where I took in the Maine Maritime Museum and Bath Iron Works (where many American warships were constructed in WWII—and are still being built). I also visited the Revolutionary War fort at Ticonderoga, on the border between New York and Vermont.

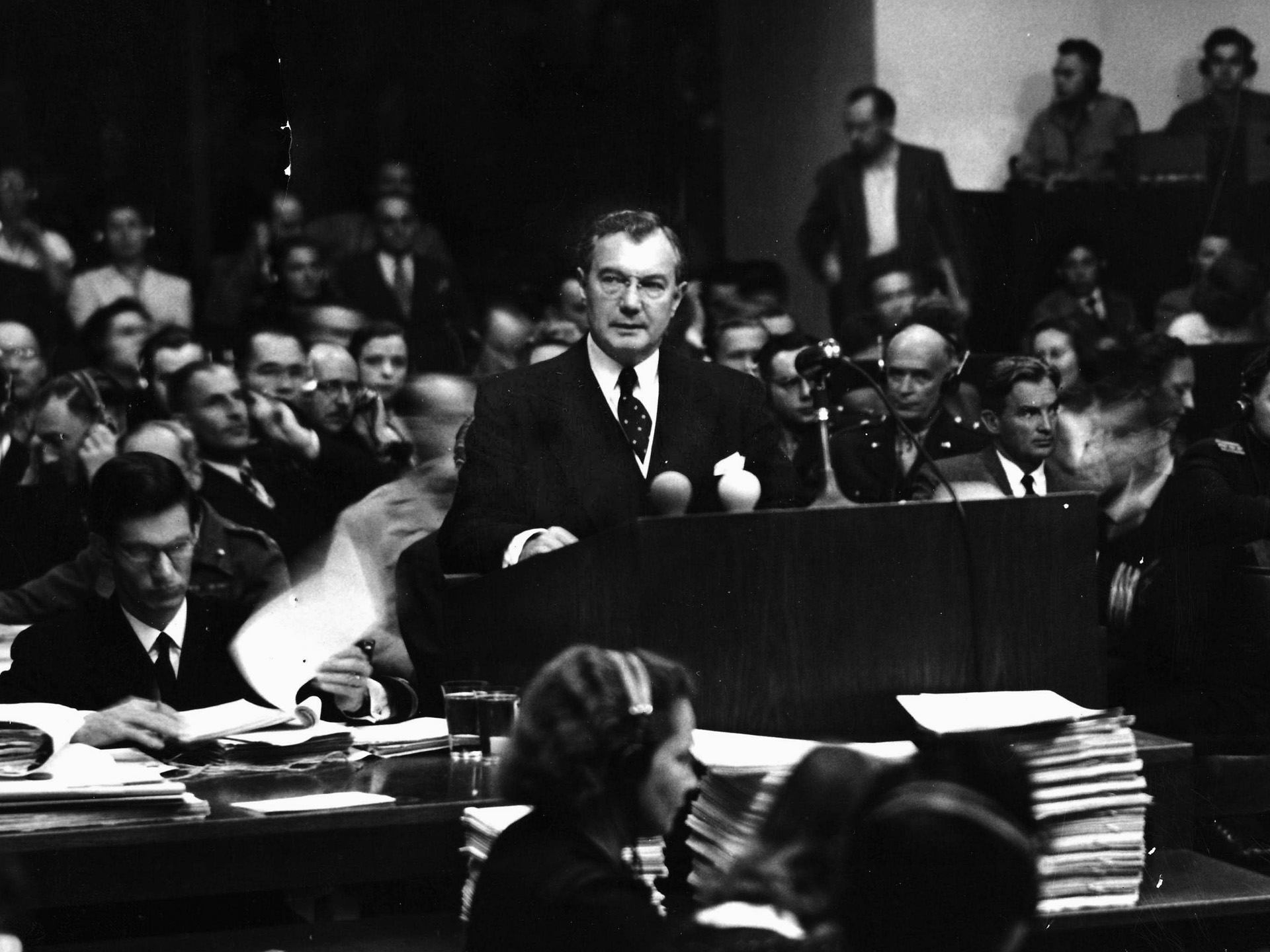

My travels also took me to Jamestown, New York, the hometown of the late Robert H. Jackson, where a fine museum pays homage to his life. Jackson was the Chief U.S. Prosecutor at the first War Crimes Tribunal that was held at Nuremberg from November 1945 to September 1946.

According to a handout from the Robert H. Jackson Center, the jurist “came from a humble background, was largely self-taught, and never ran for political office. Yet he became one of the greatest statesmen of the 20th century.”

At the time a member of the U.S. Supreme Court, Jackson was named by President Harry S, Truman in June 1945 to serve on this tribunal for the purpose of bringing 22 high-ranking Nazis to justice.

A superb orator, Jackson was at his finest at Nuremberg, remarking in his opening statement, “The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant, and so devastating that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored, because it cannot survive their being repeated.”

Like a bulldog, Jackson, along with prosecutors from Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union, went after the accused (they weren’t called defendants) with justifiable zeal.

“If we can inculcate the idea that aggressive war-making is the way to the prisoner’s dock, rather than the way to honors,” Jackson said, “we will have accomplished something toward making the peace more secure.”

For the tribunal’s second session, Jackson prepared a 20,000-word statement that made several points: “The real complaining party at your bar is Civilization. Civilization asks whether law is so laggard as to be utterly helpless to deal with crimes of this magnitude …

“We will not ask you to convict these men on the testimony of their foes. There is no count in the indictment that cannot be proved by books and records … These defendants had their share of the Teutonic passion for thoroughness in putting these things on paper.”

In February 1946, Jackson cited precedents and gave a warning for our own time by noting that the Ku Klux Klan flourished in the U.S. at about the same time as the Nazi movement began its growth in Germany.

“It [the KKK] appealed to the same hates and practices, the same extra-legal coercions, and likewise terrorized by weird nighttime ceremonies. Like the Nazis, it was composed of a core of fanatics but enlisted the support of respectable persons who knew it was wrong but thought it was winning.”

Tens of thousands of Germans who were complicit in the “crime of the century” escaped justice, and only a handful felt the full force of international law. Nevertheless, Jackson stands as a towering figure in the quest for justice for the millions of Nazism’s victims.

—Flint Whitlock, Editor

[email protected]

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments