By Wil Deac

At 11:30 pm on December 22, 1948, four handcuffed men were led by guards into the chapel of Tokyo’s Sugamo Prison. Flickering candlelight and pungent incense provided a funereal setting for their Buddhist chants. One of the men was Hideki Tojo, the wartime premier of Japan whom the Allies considered the “archcriminal of the Pacific War.” Two others were generals whose troops had committed some of the war’s worst atrocities, including the infamous Rape of Nanking. But it was the fourth general who held the dubious honor of having been convicted in the Tokyo war crimes trial of the greatest number of counts. His name was Kenji Doihara. The four were to be executed one minute after midnight.

Doihara was born into a humble Japanese family in Okayama in 1883. He grew up to become a ruthlessly ambitious believer in Japan’s expansion into and control over eastern Asia. It was an ambition that led him into a career that earned him the sobriquet “Lawrence of Manchuria.” But Doihara’s accomplishments, however motivated and carried out, were unquestionably greater than those of the better known, largely myth-surrounded T.E. Lawrence of Arabia.

An Early Flair For Languages… and Manipulation

Doihara enrolled in the army’s military academy, where he was a scholastic success and showed a flair for languages. It was said that he was fluent in nine European languages in addition to several Chinese dialects. One acquaintance, however, insisted that Doihara’s “spoken Chinese was nothing marvelous.” The extroverted Doihara also displayed a talent for mixing easily with people and being able to manipulate them. It seemed only natural that his military career choice would be channeled into intelligence. It also seemed logical that he would become a specialist on the great land mass to Japan’s west and south—China. Much of his knowledge was gained while traveling in China in various guises.

China then was a country in great disarray. Growing poverty and the incompetence of its ruling Manchu Dynasty made China prey to the territorial and economic ambitions of foreign countries. This resulted in a series of uprisings and the fall of the Manchus in 1912. A newborn Nationalist government established in the southeast initially was too weak to unify the vast nation. The rest of China was controlled by individual groups and warlords who often were in conflict with the central government and each other.

Japan Expands Its Imperialism

During the period between the two world wars, Japan itself was undergoing a period of inner turmoil, although not like China’s. Encouraged by victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 and the absorption of German Far East possessions after World War I, Japanese extremists gradually gained ascendancy over their more democracy-minded countrymen. Ultra-nationalistic military and civilian groups proliferated, urging that Japan return to its “true character and values” and spread its “imperial way” throughout the East. One of these groups, the Issekikai (One-stone) military officers’ society for the “purification” and militarization of Japan, claimed Tojo and Doihara as members. This radical trend was accelerated by the global depression, which intensified the country’s need for raw materials and trade markets. Attempted coups and assassinations by the extremists became common.

China’s instability and Japan’s tilt toward militarism were made to order for the growing Japanese desire to expand its influence on the Asian mainland. Doihara and other radicals believed that a good first step would be the takeover of Manchuria, China’s large northeastern region abutting Russia and Korea. The latter already had been absorbed by Japan and renamed Chosen. The focus on Manchuria’s three provinces was no accident. Militarily, the region was a buffer between Japan and Russia. Economically, 75 percent of the investments there, including the vital South Manchurian Railway Company, were Japanese. About a million Japanese subjects, mostly Korean, lived in Manchuria. The greatly politicized Kwantung Army was installed in southern Manchuria to protect these interests. During the 1920s, that army, named after the tip of the Liaotung Peninsula where its headquarters was located, became almost autonomous and allied itself with extremist elements in Tokyo. It also developed into Japan’s most powerful army unit.

Prostitutes and Opium Dens Yield Vital Secrets

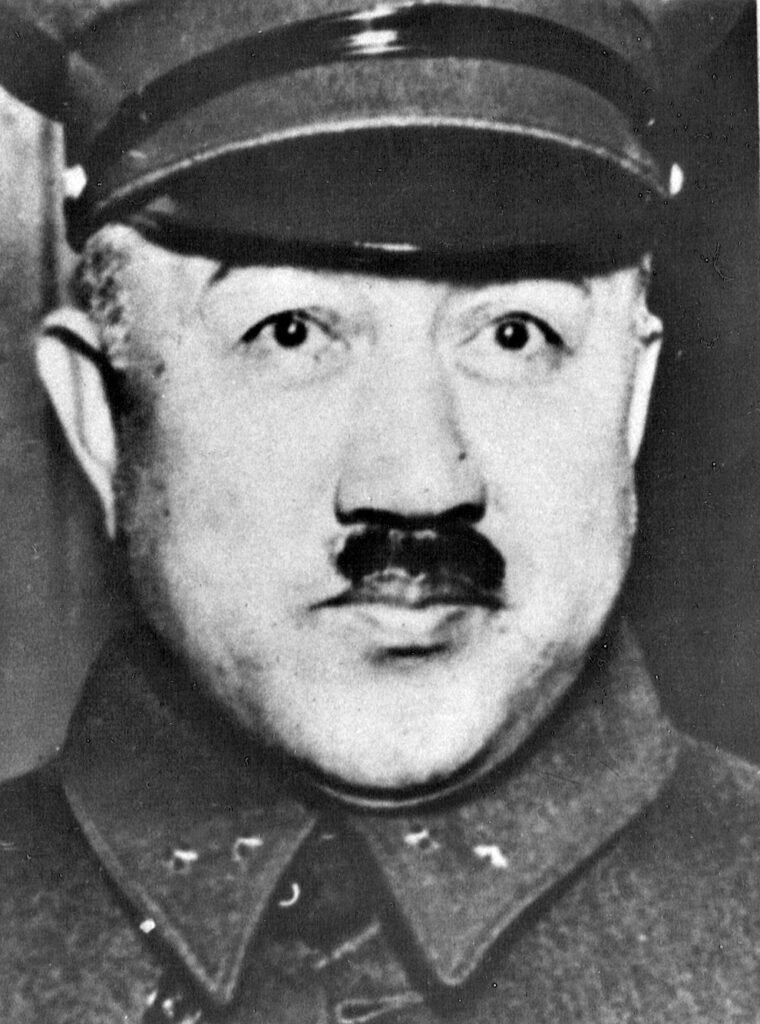

Doihara, pudgy with a crew cut and a Charlie Chaplin mustache, first gained prominence after WWI. Promoted to major and assigned as assistant military attaché to the mission in Peking, he used his persuasive personality and language fluency to recruit agents and collaborators. Among these were prostitutes tasked with coaxing secrets from important brothel visitors. As true then as today, many of the women became virtual slaves through drug addiction. Doihara encouraged this by using his contacts to set up opium dens. He also promoted an organization of influential Chinese businessmen and politicians, then persuaded them to sell Japan commercial concessions in Manchuria. Of course, these affairs generated profits, much of which financed intelligence operations. Added to the large number of Chinese recruited by Doihara were a great many White Russians, those who had fled their country after the Communist revolution. Going a step further, the Japanese spymaster honed his skill as an agent provocateur, creating incidents in order to take advantage of them. In October 1930, for example, he orchestrated a violent clash between Chinese and Japanese policemen as the result of the importation into China of thousands of Koreans. The violence gave Tokyo an excuse to introduce army troops into Chinese territory to “protect Japanese subjects.”

Chinese Nationalists Prove to be an Obstacle

Doihara’s intelligence reporting, added to other evidence that a Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek would be able to unify China, contributed to Japan’s ultimate decision to cut Manchuria off from China and set up a puppet government. A key figure in Japanese planning was Chang Tso-lin. Chang, a financially subsidized Japanese ally for years, was northern China’s most powerful warlord. He was at the time in Peking, just below the Manchurian border, directing his army against the advancing Nationalist forces that threatened to absorb his northern fiefdom.

Friction developed between the warlord and his sponsors when the Japanese advised Chang to make a strategic withdrawal to Manchuria. “My war is Japan’s war,” Chang defiantly replied. “What am I to make of Japan’s good faith in advising me to return to Manchuria?” Nevertheless, persuaded by the Nationalists’ overwhelming strength and Japanese threats to take over from him, the warlord agreed to pull back to his home base at Mukden nearly 400 miles to the northeast. Manchuria’s largest city also was the home of about 12,000 of the Kwantung Army’s troops.

Doihara Orchestrates Provocation to Remove Warlord

While the powers-that-be in Tokyo debated steps to advance their interests on the mainland without igniting all-out war, Doihara and senior staff officers of the Kwantung Army led by Colonel Daisaku Komoto decided to act. They believed that removing the mercurial Chang, who enjoyed Japanese money but bridled against its control, would provide justification for them to take over and keep the Nationalists out. On the night of June 3, 1928, shadowy figures walked onto the South Manchurian Railway bridge just outside Mukden. They stopped where the span crossed the Peking-Mukden railroad tracks. The explosives they carried were secured beneath and beside the northern and central sections at the bridge’s northern pier. Japanese soldiers had assured them that the nearest Chinese guards were at least 600 feet away.

As the train bringing Chang Tso-lin back to Mukden approached the bridge at dawn on June 4, the warlord’s Japanese adviser excused himself to buckle on a sword in preparation for arrival at the station. The sword just happened to be in a forward car. He left Chang and his closest military and civilian staff in the rear coach, which passed beneath the South Manchurian Railway bridge shortly before 5:30 am. The planted explosives were electrically detonated at that precise moment. A tremendous blast shattered the upper portion of the railroad car, leaving the undercarriage intact. Manchuria’s grievously wounded warlord was rushed to the hospital, where he died. His most trusted lieutenant, the acting governor of Manchuria, was killed instantly. Chang’s chief of staff, foreign affairs vice minister, and private secretary were badly hurt, as were the ministers of war, agriculture, and education. More than 20 others were slain or injured. Two Chinese scapegoats brought for the occasion were bayoneted to death as “proof” that Chang had been assassinated by rival warlords; however, a third Chinese escaped before he could be killed. He ran to tell the dead warlord’s son and successor, Chang Hsueh-liang, what had happened. Wisely, young Chang did not let on that he knew the truth.

The plotters’ hopes that the Kwantung Army would be mobilized to take over Manchuria were dashed when the Japanese counsel in Mukden, backed by Tokyo, refused to do so. Although the militarists failed to achieve their immediate goal, their successful defiance of the Tokyo government, which was well aware of what was going on, without being punished ensured their future success.

Doihara’s Star Rises

Doihara’s career moved forward in 1931 when he was named head of the Kwantung Army’s intelligence arm, the Tokumu Kikan(Special Services Department). After Chang Hsueh-liang, predictably spurning Japanese enticements and threats, publicly announced allegiance to the Chinese Nationalists, Doihara, now a colonel, intensified his covert actions on behalf of the militarists. These ran the gamut from using Koreans to encroach on Chinese farmland to expanding his espionage network. Four of his spies, one a Japanese army captain, were caught by the Chinese and shot in mid-1931. In July and August, Doihara moved about Manchuria cultivating susceptible local warlords into becoming allies of the Japanese. He was determined to create a “serious incident” to “justify” the takeover of Manchuria, while at the same time catering to world antiwar opinion.

In September 1931, Doihara traveled to Tokyo where, among other chores, he gave fellow militarists in the capital a progress report on the Kwantung Army’s Manchurian conspiracy. He returned to Mukden with 20,000 yen to help finance the plotters’ activities. The latter included sending propagandists throughout Manchuria to arouse anti-Nationalist sentiment. Despite efforts to keep the militarist plotting secret, there were enough leaks to cause grave concern among the country’s democratic elements. Letters from the war minister and the chief of the general staff were given to a staff officer to deliver to the Kwantung Army commander. The letters warned Lt. Gen. Shigeru Honjo against creating any aggression-provoking incident. Unfortunately, the messenger chosen was one of many who formed the Tokyo end of the conspiracy.

A Well-Planned “Incident”

Major General Yoshiji Tatekawa arrived in Mukden with the letters on September 18, 1931. As apparently arranged between himself and Doihara, Tatekawa said he would wait until the next day to see Honjo. The Tokyo letter bearer was asleep on his futon in a teahouse in the Japanese Quarter well before midnight, after being feted by sake-bearing geishas. A telegram went out from Doihara’s Mukden office to Tokyo during the early hours of the new day. It indicated that at 10:30 pm the previous night a Chinese Army unit had blown up a section of the South Manchurian Railway and assaulted a Japanese Army barracks. Of course, it explained, the Kwantung Army was moving against the “aggressors.” A short time later, a second cable flashed out, this one to the commander of the army in Korea asking for reinforcements.

What would go down in history as the Manchurian Incident had been well planned. Soon after Tatekawa was tucked safely out of the way, a unit of the Japanese 2nd Railway Battalion planted 42 small bundles of explosives a few feet from the railroad tracks only about a mile from where Chang Tso-lin had been murdered. To the east lay Mukden’s ancient walls, to the west the main barracks of the younger Chang’s garrison. The rest of the Japanese unit, the 3rd Company, positioned itself just north of the barracks. At about 10:25 pm, the explosives went off, obviously more for effect than damage. A passing Mukden-bound train continued to the city undamaged. The Chinese detachment sent to investigate the blast was attacked. Immediately afterward, having waited just long enough to claim they were reacting, the plotters ordered the remainder of the 2nd Battalion and the 29th Regiment to assault the Chinese barracks and city fortifications. Shells from two 9.5-inch howitzers that had been secretly trucked in began arcing into the barracks and the city airport. When the Japanese counsel demanded an end to the fighting, he was told, “The army will deal with this in the way it was planned.”

Deception Leads to the Death of Japanese Democracy

By 7:30 am, Mukden had fallen. Doihara became its mayor to ensure control. A combination of withholding information from and misinforming the Tokyo government, plus further incidents contrived by Doihara, enabled the Kwantung Army to expand its aggression during the months ahead. The conquest of Manchuria was complete by early 1932. Tokyo’s subsequent reluctant acceptance of the Manchurian Incident with Emperor Hirohito’s acquiescence provided the death knell to democracy in prewar Japan. The Western democracies, mired in the economic morass of the Great Depression, failed to lend the non-militarists in Tokyo the timely strong support with which they might have turned the tide. By the time the League of Nations labeled Japan an aggressor, it was too late.

The Kwantung Army’s next step, an attempt to legitimize its aggression, was the “establishment of a new administrative regime in South Manchuria,” as Tatekawa expressed it. That “new regime” would be a puppet one under a figurehead leader. Hsuan Tung, the 25-year-old last Emperor of the Manchu Dynasty, was tapped for the role. Doihara undertook the task of convincing Hsuan Tung to agree to the rogue army’s plans. Chang Hsueh-liang’s forces were to be neutralized by aerial bombardment, and world attention was to be diverted by lies and Japanese-instigated violence in the Chinese metropolis of Shanghai while the Kwantung Army consolidated its hold over Manchuria and transformed it into a new “independent” nation.

China’s Last Emperor and Japan’s Puppet Assumes Throne

Hsuan Tung, whose personal name was Pu Yi, had been allowed to retain his title of Emperor, and was given a pension and luxurious quarters after his ouster in 1912. The slim, bespectacled Pu Yi, who had been close to his British tutor, also took on the name Henry, in honor of past English kings. His wife was dubbed Elizabeth. Pu Yi received Doihara in his Tientsin villa about 70 miles southeast of Peking. “After politely inquiring about my health,” the Emperor later wrote, “he got down to business.” Doihara, using the persuasiveness he had perfected over the years, presented Japan’s side of developments in Manchuria. He asked Pu Yi to return “to the land from which my ancestors had risen to undertake the leadership of the new state” in Manchuria that would be “independent and autonomous.” The younger man later claimed that it was Doihara’s “gambler’s ability to keep a straight face while lying” that convinced him to agree to become Manchuria’s monarch. Given Pu Yi’s position and aspirations, he probably did not need much convincing.

Doihara grew impatient as the days passed and Pu Yi remained in Tientsin, especially when the spymaster learned that the Nationalist government was pressing his prey to stay in China. Furthermore, the Empress opposed Pu Yi’s going to Manchuria. Doihara decided to hurry things along. A basket of fruit containing two grenades was delivered to the Emperor. Providentially, Japanese officers arrived to remove the explosive devices. Pu Yi was told they came from Chang Hsueh-liang, so “the sooner you leave the better.” Over the next two days, there were threatening letters and a telephone call warning of “suspicious people” sent by Chang to inquire about Pu Yi. The latter did not realize that his personal assistant was on Doihara’s payroll. The Japanese spymaster’s final persuader was the creation of violence in the city center. The Japanese Concession, one of a number of foreign-controlled zones in major Chinese cities and the one in which Pu Yi lived, declared an emergency. Armored cars surrounded the imperial villa for his “protection.”

Chinese Emperor Spirited to Manchuria Under Japanese Guard

Pu Yi finally left, in the trunk of his convertible, after dark on November 10, his flight covered by the confusion of the days-long rioting. At a Japanese restaurant, the young Emperor was disguised as a soldier. He was next conveyed in a military car to the nearby Pai River in the British Concession. There he boarded a launch and motored downstream with an escort of Japanese guards. The launch ultimately reached the open Gulf of Chihli after a brief shot-punctuated encounter with a Chinese riverbank outpost. The transport Awaji Maru was waiting to take Pu Yi to the Manchurian port of Yinghow. Instead of the cheers of welcoming crowds he had been led to expect, the Emperor was received ashore by a group of Kwantung Army officers and men. A train carried him inland to a requisitioned resort hotel while the militarists smoothed the groundwork for his new regime.

If Pu Yi was to be a ruling Emperor, he would have to have an Empress, his wife Wan Jung (Beautiful Countenance), by his side, isolated from anti-Japanese influence. The Empress had distanced herself over time from both the artificial imperial life and her husband. Instead, she sought solace from opium and morphine.

Chinese Mata Hari Coaxes Empress to Join Husband

Doihara assigned the task of getting Wan Jung out of Tientsin to Yoshiko (Eastern Jewel) Kawashima, a distant relative of Wan Jung and a Japanese agent. Born in 1906, the daughter of a Manchu warlord prince who had fought rivals that included Chang Tso-lin, Kawashima was adopted by her father’s Japanese military adviser. Pretty, petite, and promiscuous, she became the lover of Major Ryukichi Tanaka, Doihara’s counterpart in Shanghai. She developed into an accomplished spy and agent provocateuse with a penchant for wearing men’s clothing. A houseguest of Pu Yi and his wife in Tientsin in 1928, Yoshiko had gotten along so well with the Empress, who envied her liberated lifestyle, that the two had kept in touch.

Yoshiko found the Empress in a poor mental and physical state, not surprising given the confusion of her existence. Cleverly exploiting their friendship, Doihara’s agent reassured Wan Jung and prepared her to join her husband. Pu Yi, as part of a drawn-out royal runaround, had been taken to a house belonging to Yoshiko’s brother. The house, located at Port Arthur on Manchuria’s Liaotung Peninsula south of Mukden and across the Gulf of Chihli from Tientsin, had been requisitioned by the Japanese.

The Emperor’s reunion with his spouse about a month and a half after his flight was brief and cool. Yoshiko, her mission accomplished, returned to Shanghai a few days later, leaving Wan Jung alone with her disillusionment and Japanese-supplied opiates. The female agent, who was called the Chinese Mata Hari and, more improbably, the Joan of Arc of Manchuria, continued her various activities on behalf of Japan and her own interests throughout World War II before being captured and executed by the Chinese she had betrayed.

Japanese Secure Holdings in China & Annex More Territory

A puppet Chinese committee obediently proclaimed Manchuria an independent state on February 17, 1932. Five days later, Pu Yi, to his dismay, learned that he would be the “chief executive” of the new Republic of Manchukuo with his capital at Changchu, about 180 miles northeast of Mukden. Manchukuo (Manchuland) was formally announced to the world on March 1. Japanese officials posing as Manchurians were positioned throughout the government to direct it. All of this was accomplished by the Kwantung Army without official government approval. Only on September 15 did Tokyo recognize the new entity. It was an easy following step for the Kwantung Army, with Doihara using his special talents to ease the way, to move deeper into China, annexing newly acquired territory into Manchukuo. With the latter now firmly in hand, the Japanese in March 1934 at last satisfied Pu Yi’s ego by promoting him to Emperor, with the new appellation of Kang Teh (Exalted Virtue).

With the defeat of Japan in 1945, Pu Yi was to become a prisoner of the Soviet Union. As such, he was a pawn in Stalin’s unrequited hope to use China’s post-WWII civil war to control Manchuria as he had Mongolia. Lent by the Soviets to testify at the Tokyo war crimes trial (where Doihara glared at his evasiveness), Pu Yi was turned over to China after the Communist seizure of power. He was tried there for war crimes in 1950 and pardoned nine years later. The former Emperor worked first as a gardener, then in the Department of Historical Archives, before his death in 1967.

Doihara Continues His Dirty Dealings in China

Doihara, upgraded to general rank in 1932, perpetuated the techniques that had proved so successful in the past. He traveled far and wide, making deals and setting up networks. During the spring of 1935, for example, he met with one of Chiang Kai-shek’s generals, who later became puppet mayor of Shanghai.

The general was only one of numerous agents Doihara planted at various levels of the Nationalist government. He also met with a Chinese man who had a virtual monopoly on opium trafficking in the southeastern province of Fuchien. Another contact was the Manchukuo regime’s public relations chief, a longtime drug trafficker who, after facilitating Doihara’s covert activities, went on to consolidate the Shanghai opium trade in 1938. The drug traffic, boosted by the taking of the “poppy province” of Jehol, served a number of purposes, including sedating conquered territory and making money. Prostitution provided both information and profit. More funds and control came from business monopolies, extortion, blackmail, kidnapping, and bribery.

Japanese Desires in Northern China Lead to Pacific War

As part of the Kwantung Army’s plan to split northern China from the rest of the nation, Doihara used intrigue in an effort to create autonomous regions out of provinces that had not yet fully come under Nationalist control. As Doihara said after a tour of northern China, Japan should “lead the local regimes in North China into absolute obedience.” This continuing Japanese pressure increased the tensions that came to a head in another of the many incidents Japan used to satiate her territorial ambitions without declaring war. Whether or not Doihara was behind the latest incident, it did, in the words of one chronicler, “bear his hallmark.”

On the night of July 7, 1937, a company of Japanese troops, part of a garrison conducting maneuvers in Chinese territory, reached the centuries-old Marco Polo Bridge over the Yungting River just southwest of Peking. Shots were fired, and a battle erupted between the Japanese and Chinese. Things quieted down as a cease-fire was prepared. Then, on July 10, the Japanese reopened hostilities. The next day, Tokyo unleashed the Kwantung and other army units to move into northern China. Although efforts were made by parties on both sides to localize the incident in the face of mounting violence, this was the beginning of the Pacific War that did not end until 1945.

Doihara Assumes Command—But Doesn’t Leave Old Tactics Behind

With Japan and China now engaged in full-fledged fighting, Doihara exchanged his cloak and dagger for command of the 14th Division, and later the 5th Army, in northern China. Even then, he continued to pursue many of the tactics that had gained him widespread notoriety. Late in 1938, for example, he chaired a Shanghai conference with turncoat elements of the Chinese secret service. By early the following year, these puppets formed a security police apparatus aimed at terrorizing the city into complete submission to Japanese occupation.

Doihara also was involved in the fierce 1939 border clashes with Soviet forces that grew out of the Kwantung Army’s inroads into Outer Mongolia. In 1940, he donned the gown of principal of the army military academy, but left eight months later to become inspector general of army aviation. Doihara sat in on meetings that set the groundwork for the December 1941 attacks that brought the United States and Britain into World War II. One such meeting was the November 4, 1941, conference of military councilors attended by Hirohito himself. Doihara next held rear-area commands in China and Southeast Asia before being recalled to Japan in 1945 to help organize defenses against the expected U.S. invasion. When the Americans did arrive, without invasion after two atomic bombs were dropped, Doihara, now a lieutenant general, was included in their roundup of alleged war criminals.

A Defiant War Criminal On Trial For His Life

The controversial International Military Tribunal for the Far East began on May 3, 1946, in the military academy auditorium next door to the war ministry in Tokyo. Doihara, one of 28 military and civilian leaders accused of war crimes, was led by white-helmeted U.S. military policemen to the frontmost of two tiers on the right side of the hundred-foot-long improvised courtroom. The 11 judges, representing countries that had fought Japan, were seated directly opposite the defendants. As irony would have it, the American chief prosecutor’s right-hand man was the bear-sized, heavily mustached, and bald Ryukichi Tanaka. Tanaka, retired as a major general in 1942 because he opposed Tojo over the attack on the United States, had been Doihara’s partner in the intrigues against China and Eastern Jewel’s lover. Doihara now considered Tanaka a traitor. There were 55 counts in the 43-page indictment, ranging from general crimes against humanity to the specific making of war on China, “beginning with the invasion of Manchuria in 1931.”

Doihara’s reaction to the chief prosecutor’s opening statement was, “Even if the entire nation speaks ill of me, I will stand firm as a rock, and the value of my life won’t be impaired at all.”

Doihara Gets Religion at the Eleventh Hour

Doihara was one of the minority who refused to take the stand. His Berlin-trained lawyer denied wrongdoing by his client, claiming, for example, that Doihara “had nothing whatever to do” with the atrocities in Southeast Asia, where he had served as commander of the 7th Army. During the drawn-out trial, which included a six-month recess and did not end until November 4, 1948, Doihara and Tojo were among the defendants who adopted the Buddhist religion.

At the end of the trial, 45 of the 55 counts of the indictment were dropped. The remainder addressed conspiracy to make and wage war, and atrocities. All the accused were found guilty, with seven receiving death sentences. Doihara said that when he was condemned to hang, “all my worries left me, and almost at once I began to feel better.” Just after 9 pm on December 21, 1948, wearing army fatigues with the letter P (for prisoner) on the back, the former spymaster was taken from his 44-square-foot cell to a tiny makeshift chapel. There the prison commandant informed him that he would be executed at one minute after midnight on the 23rd.

Justice Rendered By Hangman’s Noose

Having said their prayers that fateful Wednesday night, Doihara and his three companions left the chapel and crossed a courtyard to the brightly lit death chamber. The quartet, handcuffs replaced by body straps, climbed the 13 steps of the scaffold in the center of the room. It was over in a minute and a half, the springing of the four traps sounding to one witness “like a rifle volley.” Doihara was declared dead at 12:08 am. His body was cut down and placed in a wooden coffin as the three final condemned prisoners were prepared for the hangman. The seven bodies were cremated, their remains scattered into the air.

The specifics and extent of Doihara’s multifaceted activities were such that they were more often than not unclear to those who recorded them. For example, some writers credited the Japanese spymaster with being almost wholly responsible for the events in Manchuria that lit the long fuse leading to the Pacific War powder keg. While this is a gross exaggeration, Doihara, as an important part of a powerful cabal responsible for World War II in Asia, nevertheless was to some degree involved in many of the key turning points of prewar Japanese history. Ironically, despite all his wrongdoing, he was one of the key militarists whom Asia can thank for beginning the end of Western colonialism in the Eastern Hemisphere.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments