By William E. Welsh

Union soldiers streamed across the pontoon bridge at Deep Bottom on the tidal portion of the James River in the early morning hours of September 29, 1864. Among the troops that tramped north towards the Confederate position at New Market Heights on the Chaffin Farm east of Richmond, Virginia, were three regiments of U.S. Colored Troops. Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, commanding the Army of the James, had attached the black soldiers to Union Maj. Gen. David Birney’s X Corps for the military operation that day.

The black troops felt a mixture of excitement and anxiety. Their excitement stemmed from the opportunity they would have to do battle with a Confederate army that defended a society determined to keep them in bondage as it had for the past 240 years. The anxiety was a response to the knowledge that some of them would perish in the assault on the enemy’s heavily fortified position.

Seven months after the battle, 14 men from five regiments of U.S. Colored Troops would receive the Medal of Honor for feats of valor shown that fateful day.

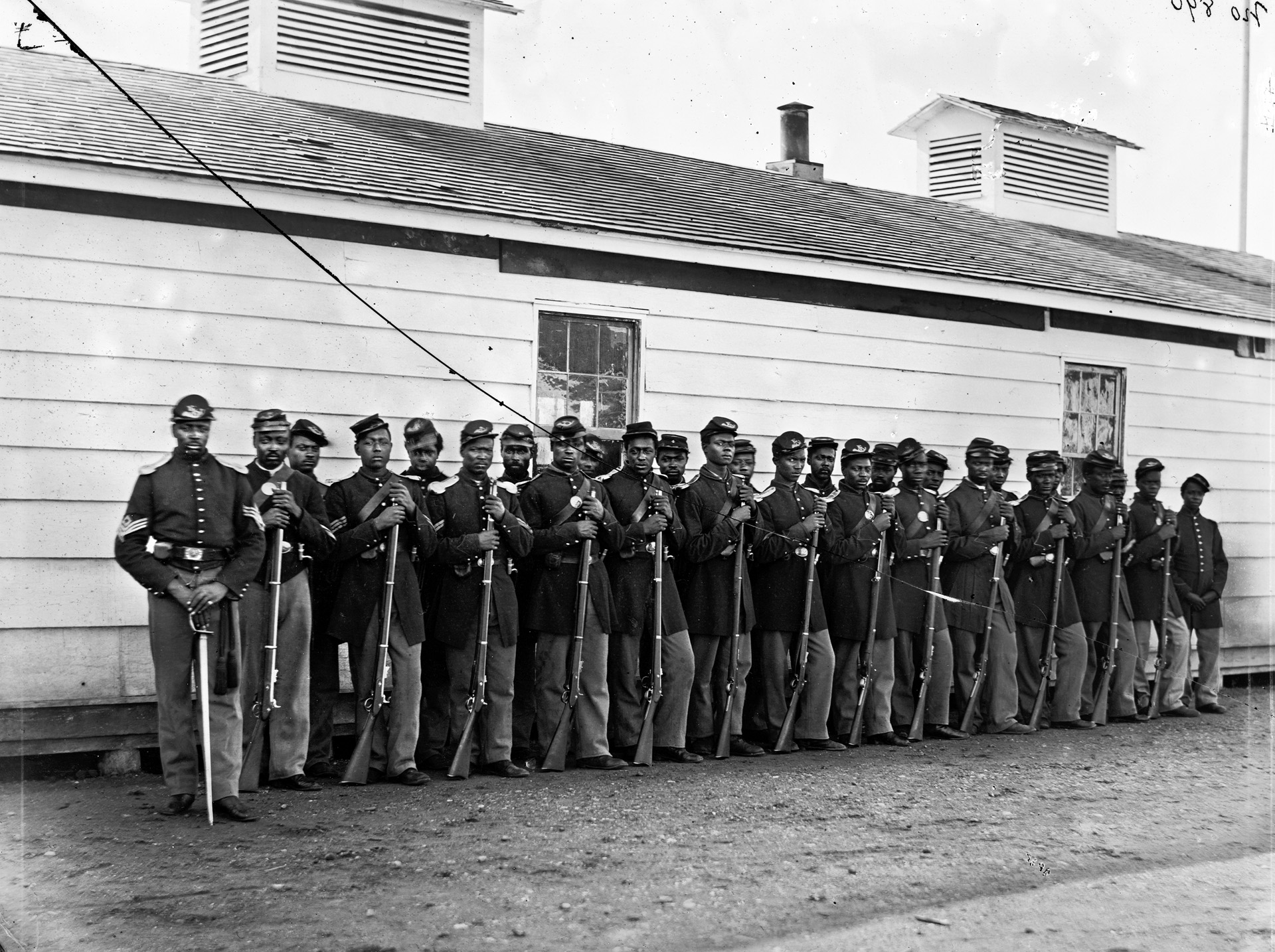

The U.S. Army began enlisting black troops into its ranks in May 1863. But they were expressly forbidden from gaining officer commissions; instead, those went to white officers who led them into battle. By the time the war ended, the army had created 145 black regiments of infantry, seven of cavalry, 13 of artillery, and one of engineers.

The attack at New Market Heights in late September 1864 constituted part of Union Army General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant’s strategic plan to wear down General Robert E. Lee’s 60,000-strong Confederate Army of Northern Virginia defending Richmond-Petersburg sector in late 1864. Grant had besieged Petersburg with 100,000 Federal troops of the Armies of the Potomac and James in mid-June 1864 in an effort to strangle the Confederate Army by cutting off the provisions flowing into the Confederate capitol over the railroads that converged in Petersburg. Since the siege of Petersburg began, Grant had ordered alternating, and sometimes simultaneous, attacks on both cities to stretch the Confederate defenses.

Maj. Gen. Winfield Hancock and Birney, commanding the II and X corps, respectively, had assailed the Confederate positions north of the James in a series of unsuccessful assaults known as the Second Battle of Deep Bottom between August 14 and August 16 at the cost of 3,000 men. Grant was keen to launch another attack in the same sector.

Lincoln had saddled Grant with Butler, a general with few skills appointed for political reasons, when he established the Army of the James in April 1864 from occupation forces in Suffolk, Va., and coastal footholds in the Carolinas. Lincoln’s decision to support Butler stemmed from the president’s appreciation for the support of the former Massachusetts democrat, who had abandoned his party in1860 and joined the ranks of the radical Republicans.

Butler had approached Grant for an opportunity to attempt to fight his way into Richmond. Although Grant was skeptical he could achieve that objective, he gave Butler permission in mid-September to proceed because it would pull some Confederate troops out of the trenches in Petersburg. Butler’s plan called for a two-pronged assault against the right and center of the Confederate defensive lines east of Richmond. Birney’s reinforced X Corps would strike the Confederate right, while Maj. Gen. Edward O.C. Ord’s XVIII Corps would assault the Confederate center. Brig. Gen. August V. Kautz’s Cavalry division was to accompany them to exploit any successes.

Ord’s troops would cross the James River on a pontoon bridge to be constructed on the eve of the attack at Aiken’s Landing. They were to march north to assail Fort Harrison. Once the fort was in Union hands, Ord would isolate any Confederate outposts south of the fort. Birney had orders to cross at the pontoon bridge situated at Deep Bottom and advance north to attack New Market Heights. If all went well, Birney was to advance into Richmond via the New Market Road, while Ord and Kautz pushed into Richmond along the Osborne Turnpike. The notion that Butler would capture Richmond was overly optimistic; nevertheless, Butler’s troops were bound to make some gains against the Confederate defenses east of Richmond.

The area where the X Corps would be fighting was a large expanse of open ground southeast of Richmond known as Chaffin’s Farm. To add extra weight to Birney’s attack, he would have the 3,800 black troops of Brig. Gen. Charles Paine’s Third Division of the XVIII Corps. Butler specifically instructed Birney to have the black troops spearhead the attack against New Market Heights because he wanted to know whether the blacks could capture a position that other Union troops had failed to capture in previous attacks.

The Confederates had constructed three concentric lines of earthen defenses to protect the Confederate capital from attack. Fort Harrison, where 1,750 troops were deployed, was the strongest of the 25 earthen forts on the intermediate defense line. As for the Confederate defenses on New Market Heights on the outer defenses, they consisted of a double line of abatis to slow an attack and multilayered breastworks. The infantry force posted at New Market Heights numbered 2,000 muskets and consisted of the veteran Texas Brigade led by Brig. Gen. John Gregg and Brig. Gen. Martin Gary’s dismounted cavalry brigade.

Under cover of darkness, the long columns moved over the bridges and proceeded north to their respective points of attack. Ord’s troops attacked first. The burden of the assault fell to the 4,150 muskets of Brig. Gen. George Stannard’s division. “They formed in line of battle, and moved up steadily toward the work,” wrote war correspondent Henry Winser of the New York Times. With drums beating and colors flaunting, they made a superb charge, carrying the fort under a severe fire. Ord was wounded in the thigh, and Hiram Burnham of Maine, one of the three brigadiers participating in the assault, was cut down by Rebel fire.

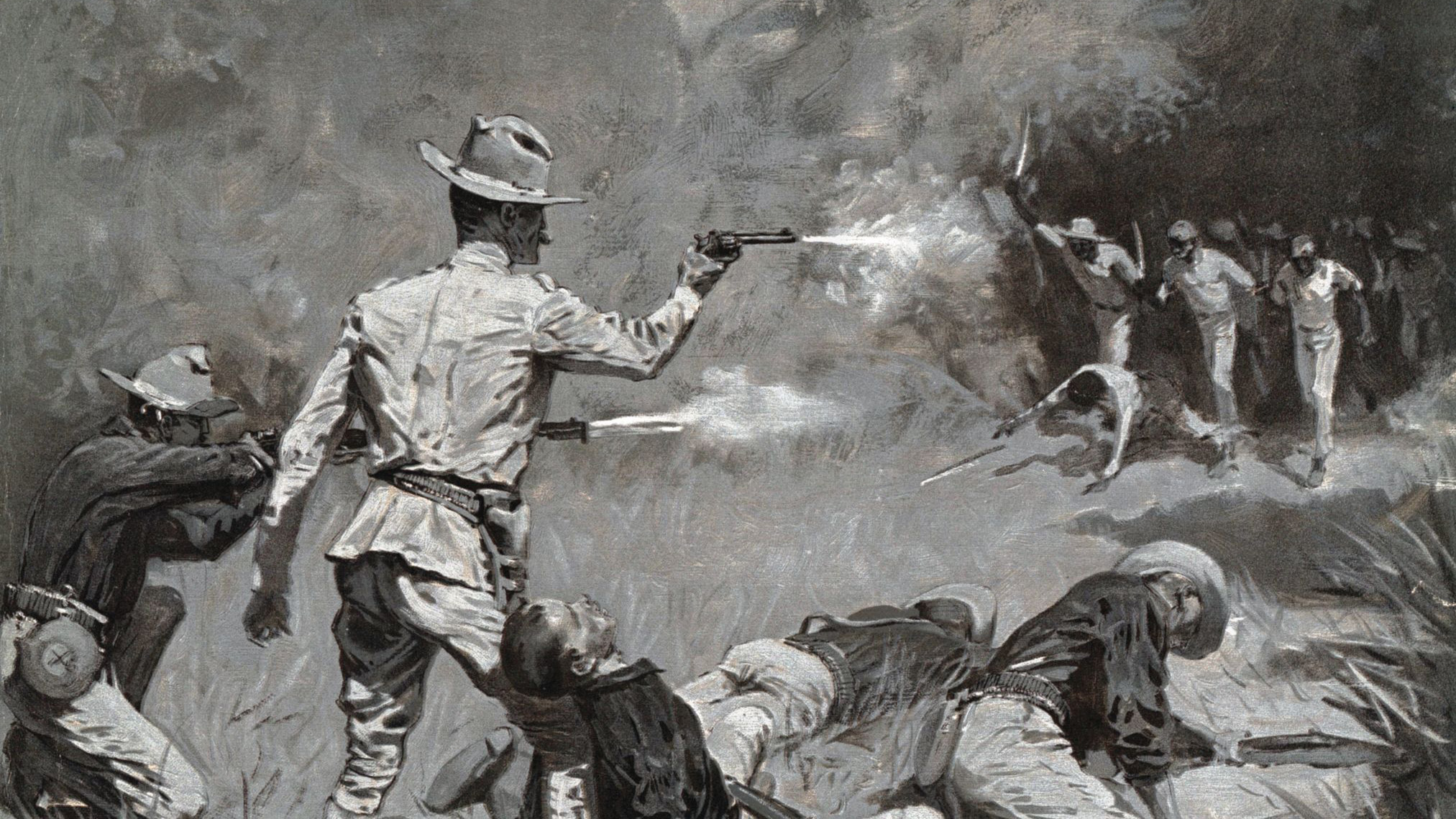

A short distance to the west, Birney ordered Paine to storm the Rebel defense on New Market Heights with his black troops while the rest of the X Corps stood by in reserve. The attack began at dawn in a heavy fog when a line of skirmishers advanced. Colonel Samuel Duncan’s 3rd Brigade, which was composed of the 4th and 6th U.S.C.T. regiments, led the assault alone. This was because Colonel John Holman’s 1st Brigade and Colonel Alonzo Draper’s 2nd Brigade both had fallen behind trying to get through the thick marshes along Four Mile Creek.

Confederate fire pinned down Duncan’s men as they tried to force their way through the abatis. The officers did their best to spur their men on, but most of them were quickly killed or wounded by Confederate fire. At that point, it fell to the black sergeants of Draper’s two regiments, the 4th and 6th U.S. Colored Troops, to lead the attack.

“When the charge was started, our color guard was full; two sergeants and 10 corporals,” wrote Sgt. Maj. Christian Fleetwood of the 4th U.S.C.T. “Only one of the 12 came off that field on his own feet.”

The attackers faced a withering fire from Colonel Frederick Bass’ 1st Texas Regiment. Sergeant Alfred Hilton, who was carrying the 4th regiment’s U.S. flag into battle, also grabbed the unit’s blue regimental flag when its color bearer was shot. Hilton struggled forward with the two flags until he was severely wounded as well. Before either of the colors could fall to the ground, Sgt. Maj. Fleetwood grabbed the U.S. flag and Sergeant Charles Veale grabbed the regimental flag. Twenty-two year-old Hilton perished from his wounds three weeks later, but both Fleetwood and Veale survived the war. All three were among the 14 black soldiers from Paine’s division that would receive the Medal of Honor for their valor during the battle.

“We struggled through two lines of abatis, a few getting through the palisades, but it was sheer madness,” Fleetwood recalled. Because the attack of the 4th U.S.C.T. was unsupported, it temporarily stalled. The Texans sallied forth from their breastworks and rounded up some of the Yankees who were closest to their lines. Fleetwood evaded capture and brought the U.S. colors back to where the reserves were positioned. The attack of the 6th U.S.C.T. met with the same results; the Texans had destroyed the first wave of the attack in just 40 minutes.

Draper’s 2nd Brigade, which was deployed to the left of Duncan’s 3rd Brigade, was the next to close with the Confederates. Draper sent his 5th regiment forward in the first rank to spearhead the attack, with the 36th and 38th regiments following in the second rank. Fleetwood and the survivors of the first attack from Duncan’s brigade went forward a second time. The men of Draper’s brigade did their best to hack their way through the abatis, but they became bogged down for 30 minutes in the sharpened stakes while under heavy fire.

“All of the officers were striving constantly to get the men forward,” Draper wrote in his battle report. “The efforts of the white officers and black noncoms yielded success.” When the Confederate fire slackened, Draper’s men broke free of the abatis and surged forward to fight hand-to-hand with the Rebels at their breastworks.

Sergeants James H. Harris and Edward Ratcliff, both of the 38th U.S.C.T., and Corporal Miles James and Private William Barnes of the 36th U.S.C.T., each of whom would receive the Medal of Honor, were among the first to fight their way into the Rebel trenches. Although these men were wounded in the attack, they refused to quit the fight. One valiant soldier, Private James Gardiner of the 36th U.S.C.T., had the distinction of killing a Confederate officer. Rushing ahead of his unit, Gardiner shot and bayoneted a Confederate officer atop the parapet rallying his men. He also received the Medal of Honor.

The battle was over before Holman’s 1st Brigade could get into action. When it became evident to Gregg that his force was too small to hold its ground against a Federal corps, he ordered his troops to fall back to positions around Fort Gilmer, which was situated north of Fort Harrison.

The U.S.C.T. brigades took possession of New Market Heights at 8:00 am. Duncan’s 3rd Brigade suffered 368 killed and wounded casualties, while Draper’s Brigade recorded 429 killed and wounded. A subsequent attack on Fort Gilmer resulted in 100 more casualties for the 5th U.S.C.T. of Draper’s 2nd Brigade.

Lee was not about to let the fall of Fort Harrison go uncontested. He ordered Lt. Gen. Richard Anderson to launch a counterattack with his two divisions the following day, but by that time Ord’s men had entrenched. Anderson failed to retake Fort Harrison; however, Lee established a new position equally strong just east of it.

Butler’s troops failed to capture Richmond, but they had driven the Confederates from key positions. The total butcher’s bill for the two-day battle: 3,300 Union killed and wounded, and 2,000 Confederate casualties.

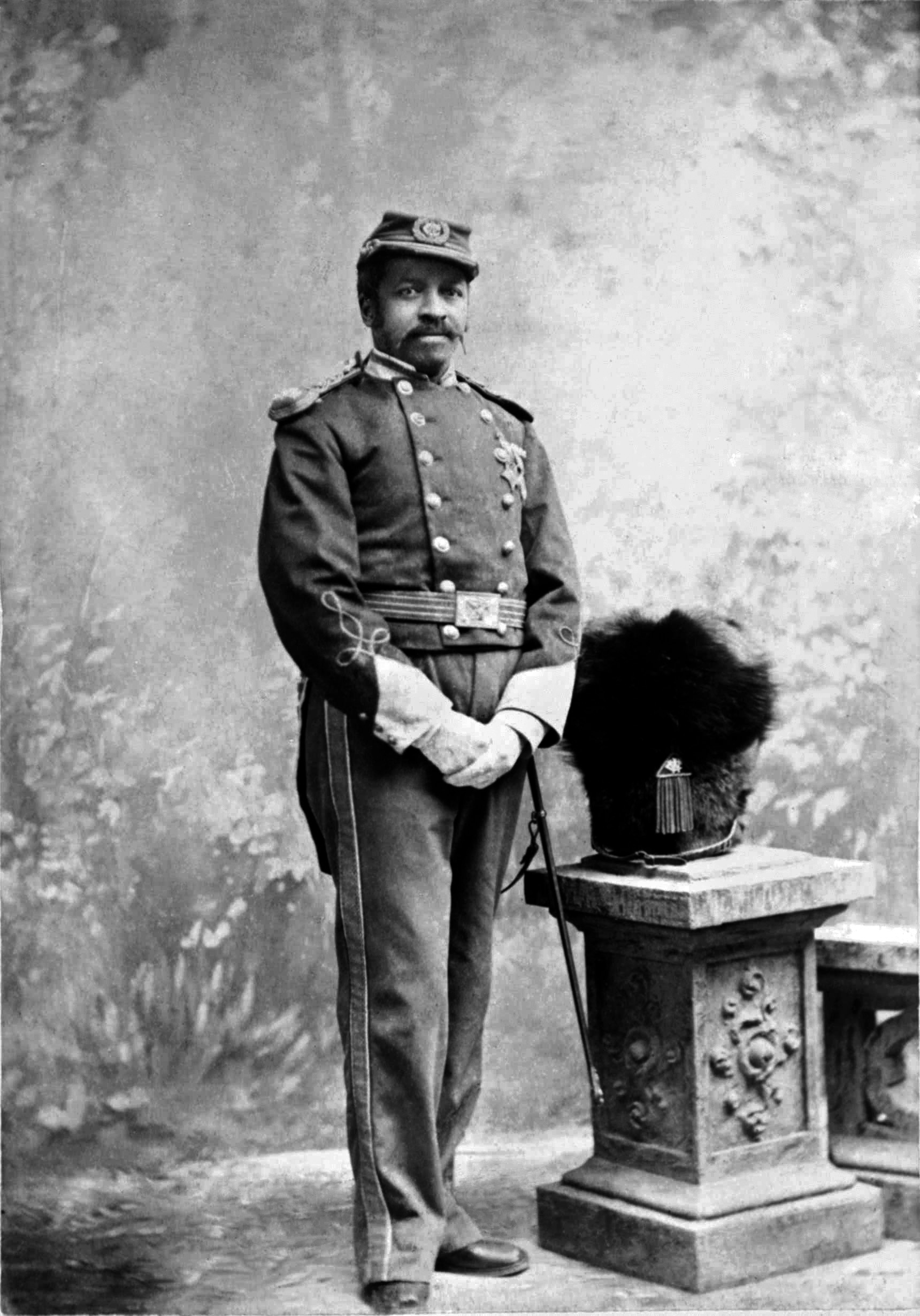

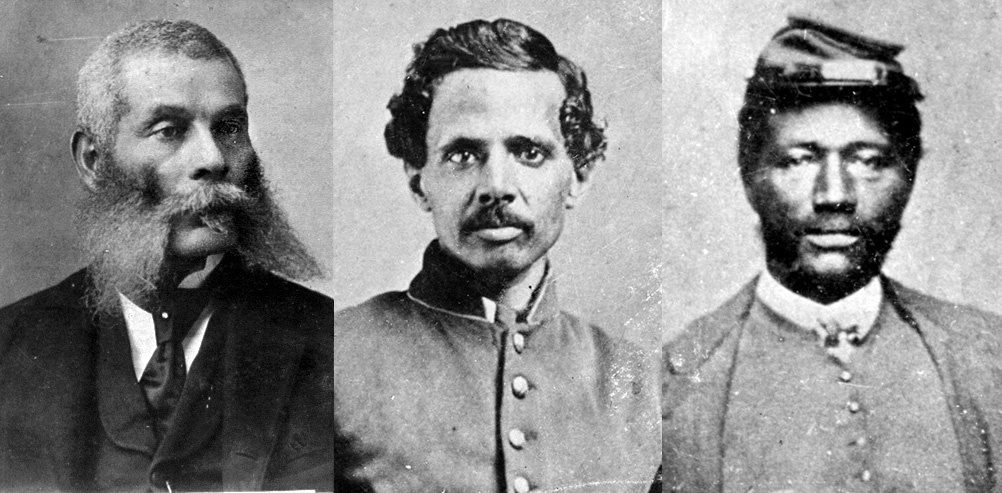

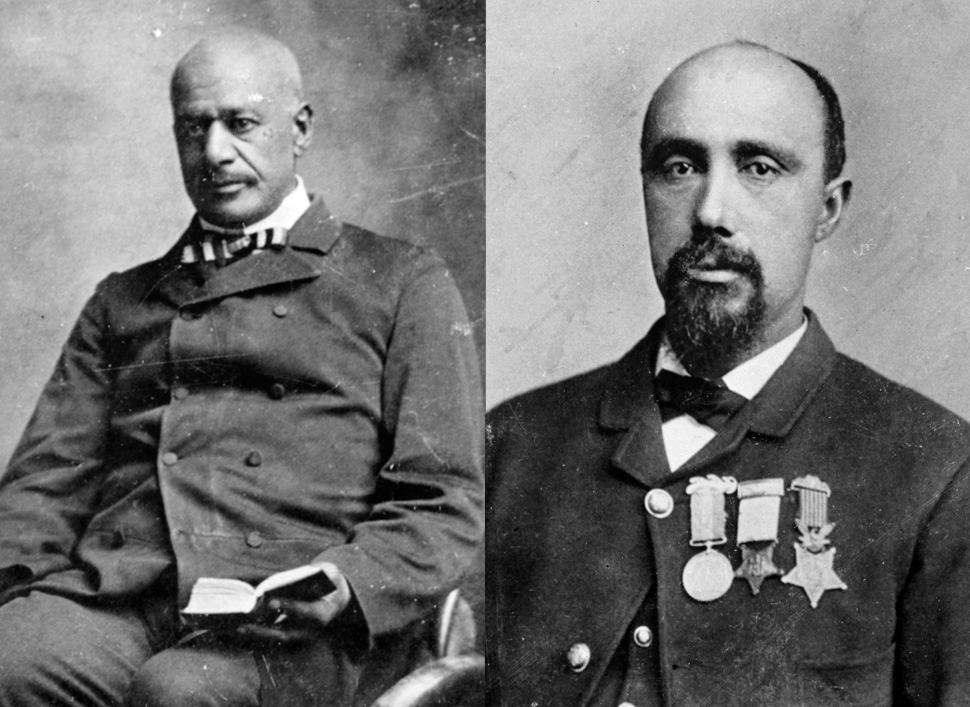

On April 6, 1865, the War Department announced the recipients of the Medal of Honor for heroism at New Market Heights. In addition to the eight aforementioned recipients (Barnes, Fleetwood, Gardiner, Harris, Hilton, James, Ratcliff, and Veale), the other six recipients were Sergeant Powhatan Beaty of the 5th regiment, Sergeant James Bronson of the 5th regiment, Sgt. Maj. Thomas Hawkins of the 6th regiment, Sergeant Milton Holland of the 5th regiment, Sergeant Alexander Kelly of the 6th regiment, and Sergeant Robert Pinn of the 5th regiment.

Maj. Gen. Butler desperately wanted to reward the black soldiers who had shown extraordinarily valor at Chaffin’s Farm. He could not promote the black sergeants to lieutenants because they were not allowed to become commissioned officers. Instead, he decided to use the Medal of Honor, which had been established in 1862. At that time the requirements for the Medal of Honor were less stringent than modern standards, yet it was still an award of great distinction. Morris Chester, a black reporter with the Philadelphia Press, waxed eloquently about the achievements of all the troops of Paine’s division. The division “had covered itself with glory and wiped out effectively the imputation against the fighting qualities of colored troops.”