By David A. Norris

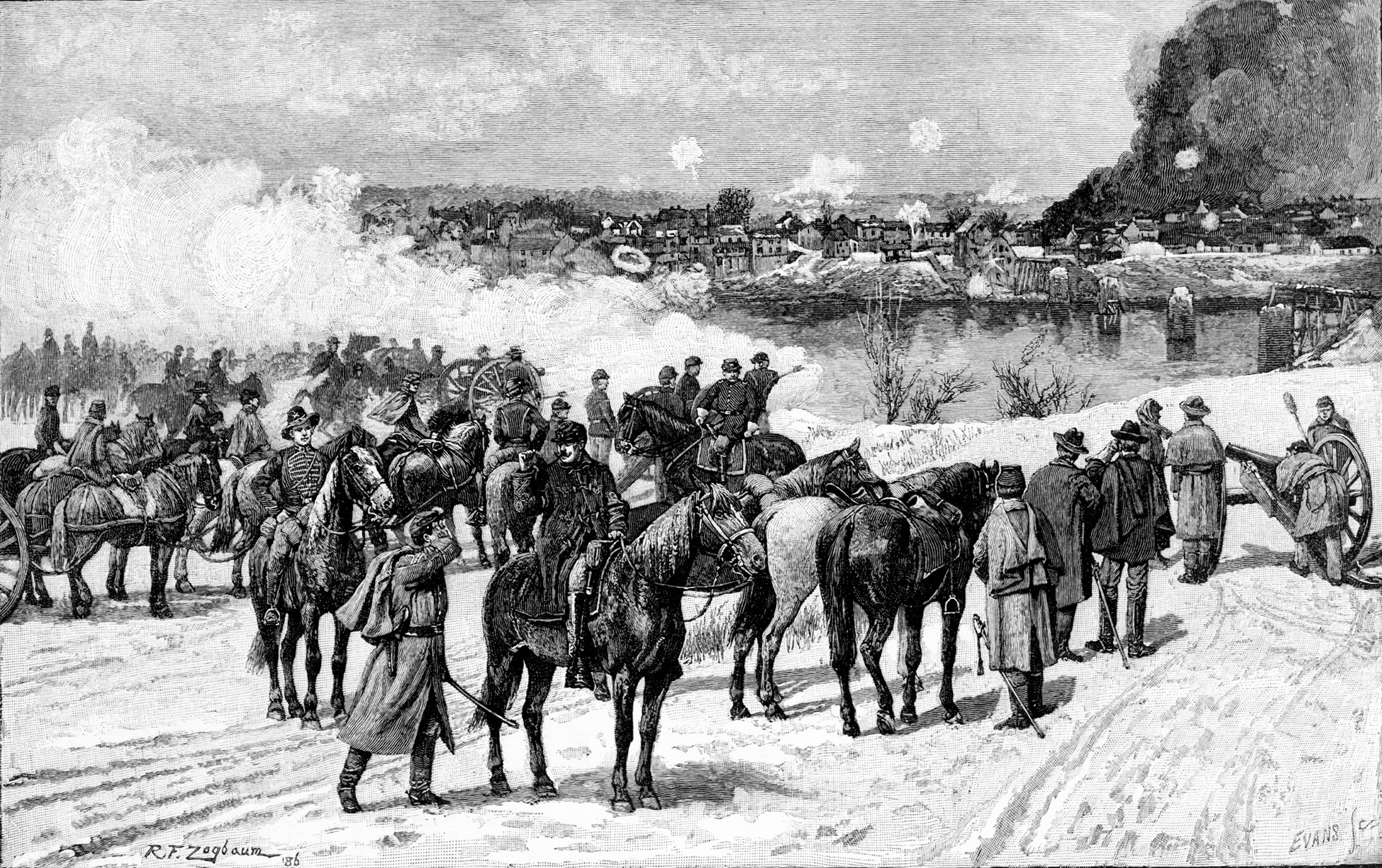

Brig. Gen. George Gordon Meade’s division spent three hours bombarded by Confederate guns on December 13, 1862. A mile to the north, Union troops began their doomed assaults against Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s unbreakable Confederate line on Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg, Virginia. Chafing under fire, Meade’s troops arose and rushed toward the Rebel lines when the commander allowed them to charge. Enemy fire took down all three of Meade’s brigade commanders. But as the Federals neared their objective, instead of a hail of musketry, they faced a silent and deserted band of trees stretching along the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad. It began to look like Meade’s charge had the potential of turning the Battle of Fredericksburg into a Union victory.

The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia’s first invasion of the North ended with the September 17, 1862, Battle of Antietam. Although blocked by the Union’s Army of the Potomac under Gen. George B. McClellan along the banks of Antietam Creek, General Robert E. Lee extracted his army from Maryland and safely crossed the Potomac River into Virginia.

U.S. President Abraham Lincoln urged McClellan to pursue Lee’s retreating army with vigor, but Little Mac, as some called him, refused to do so. For six weeks Lincoln hounded McClellan to no avail. McClellan eventually began moving his troops across the Potomac River in late October.

Long dissatisfied with McClellan for his inability to whip Lee’s army, Lincoln removed him as commander of the Army of the Potomac on November 7. Lincoln wanted a victory before the end of 1862 to keep his political opponents at bay and ease the economic pressure on the North. The president replaced McClellan with Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. Burnside made a name for himself with a successful campaign that took much of coastal North Carolina in early 1862. His performance at Antietam was less impressive, but Lincoln believed he would run the army better than McClellan. Burnside accepted command, albeit reluctantly.

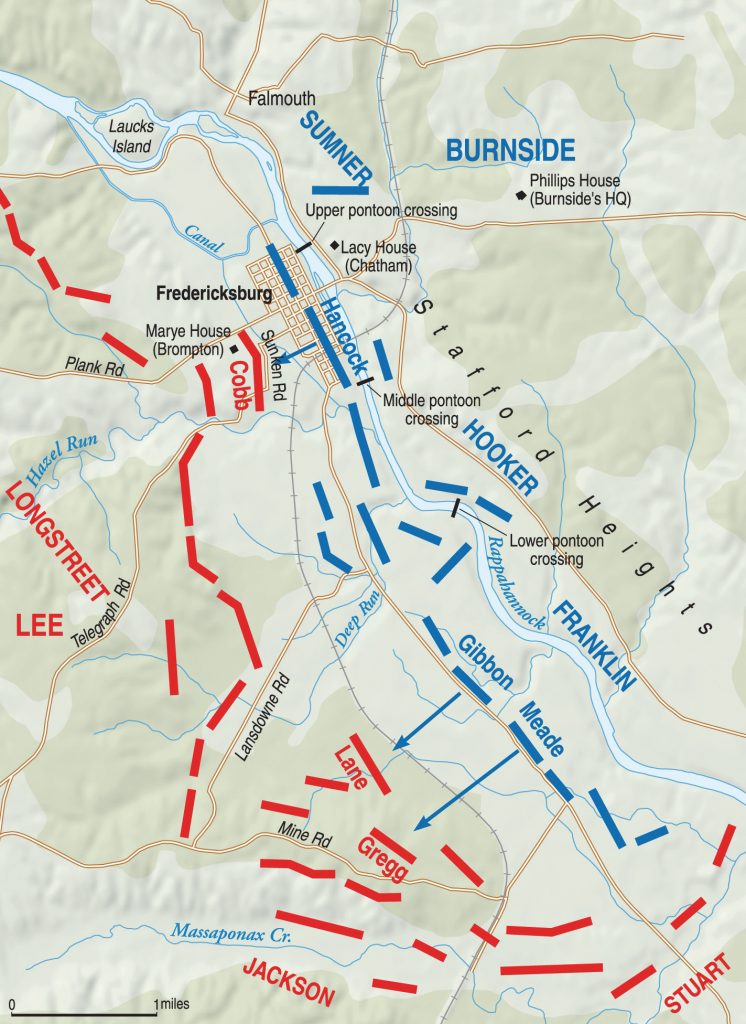

Burnside reorganized the Army of the Potomac into three so-called Grand Divisions under major generals Edwin Sumner, Joseph Hooker, and William Franklin. Designed to operate independently if necessary, each Grand Division was composed of two infantry corps, as well as supporting artillery and cavalry. After the reorganization, Burnside set his mind to how he would conduct his campaign against Lee.

Unlike the Union Army of the Potomac, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia retained its existing structure of two corps. Lt. Gen. James Longstreet commanded the I Corps, and Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson commanded the II corps. In early November, Longstreet was at Culpeper Courthouse, and Jackson’s corps was in the Shenandoah Valley.

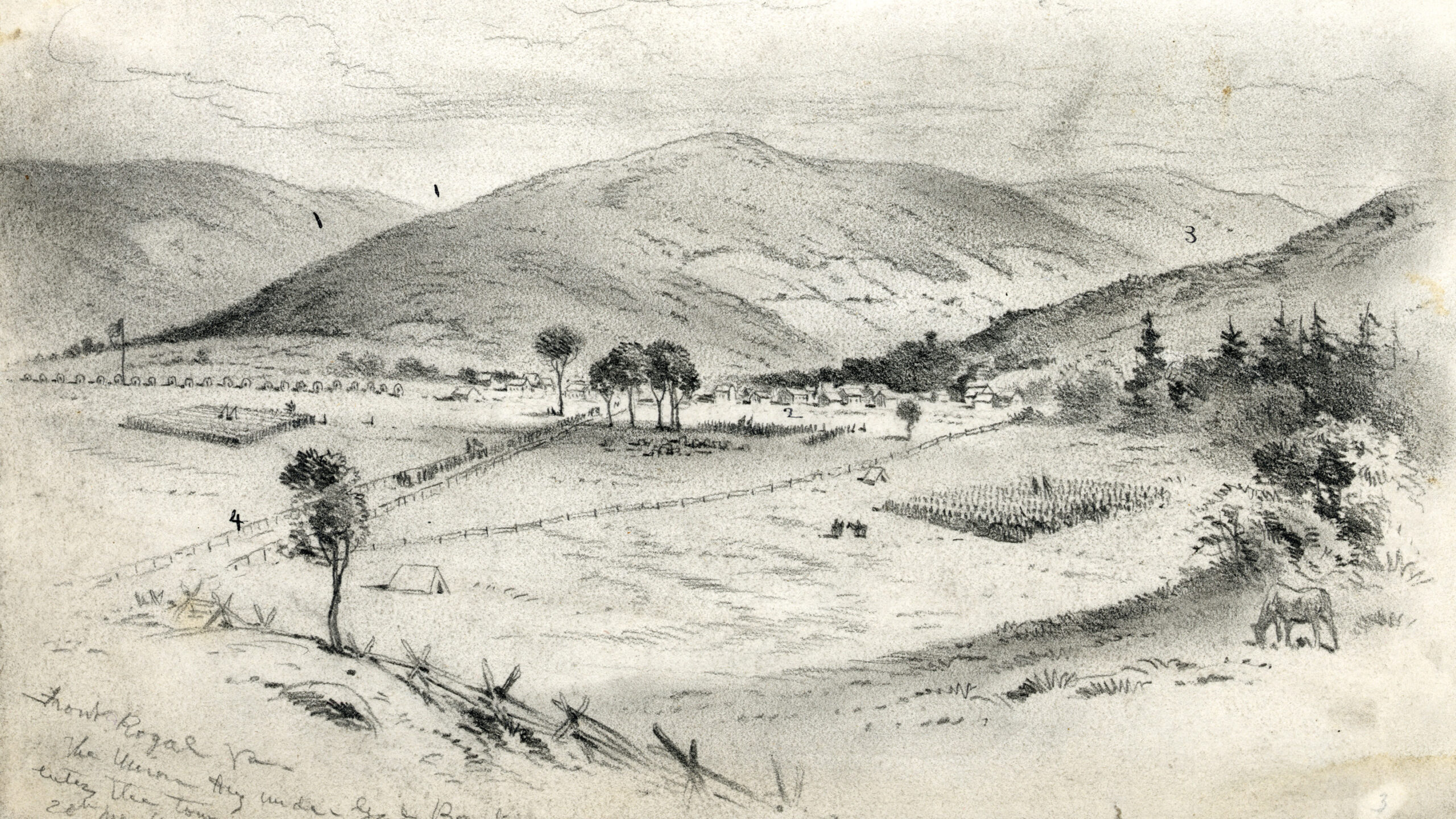

Rather than try to destroy one of the isolated wings of Lee’s army, Burnside proposed a shift in strategy. He would assemble his army at Warrenton, 50 miles southwest of Washington, and make the Confederates believe he was going to advance on Culpeper Courthouse, 20 miles to the southwest. With Lee looking for an attack on the upper Rappahannock, Burnside would shift southeastward to Fredericksburg. Ten miles from the lower Potomac River, Fredericksburg would be at the end of a much shorter supply line for the Union. And from there, the RF&P railway led to Richmond, nearly 60 miles to the south.

Lincoln was wary of Burnside’s plans, but gave permission for them while stressing that speed was of the utmost importance. After General-in-Chief Henry Halleck wired the president’s approval to him on November 14, Burnside began his campaign. Lincoln wanted Burnside to move quickly, lest Lee interfere with his plans. Sumner and the lead elements of his Right Grand Division arrived at Falmouth, on the north bank of the Rappahannock River opposite Fredericksburg, on November 17.

Colonel William Ball of the 15th Virginia Cavalry had just 1,000 Confederate troops at Fredericksburg. In compliance with Lee’s orders, Ball’s men destroyed the railroad north of Fredericksburg and burned all of the bridges across the Rappahannock to slow the Union advance. Lee was reluctant to commit his forces to the defense of Fredericksburg because Burnside had not yet established a supply base to support operations in that sector. To determine the Union army’s whereabouts, he instructed Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown (J.E.B.) Stuart to send his cavalry across the upper Rappahannock to track the movements of Burnside’s army. Stuart reported on November 15 that the Federals had abandoned Loudoun and Fauquier counties, and also torched their supply depots at Manassas and Warrenton. The logical conclusion was that they were marching on Fredericksburg.

Burnside wanted to use pontoon bridges to cross the flood-prone Rappahannock River. Because of a series of administrative blunders, the prefabricated pontoon bridge kits were still far to the rear when Sumner reached Falmouth. Examination of the river indicated that crossing near Fredericksburg without pontoons would be impossible. For that reason, the Army of the Potomac settled down to wait. Burnside decided against crossing at the fords in the region. He reasoned that it would be too risky to place Sumner on the other side of the river given that autumn rains might flood the Rappahannock before the other two Grand Divisions could get across to join Sumner’s Right Grand Division. If that were to happen, Sumner’s Grand Division might be cut off and destroyed. What is more, Burnside believed a Union crossing at the town of Fredericksburg would come as a bigger surprise to Lee.

Once Stuart had discerned that the Army of the Potomac was on the move, Lee dispatched a foot regiment and a battery to bolster the garrison at Fredericksburg. Two days later, intelligence indicated that Sumner’s corps was approaching Falmouth, and Lee dispatched two of Longstreet’s divisions to Fredericksburg. A short time later, he ordered the rest of Longstreet’s troops, as well as Jackson’s corps, to assemble at Fredericksburg.

By early December, the Army of the Potomac was assembled at Falmouth, but the pontoons were still miles away. Lee’s army was entrenched across the river at Fredericksburg. The new Rebel defenses looked so secure that Lee gave up an earlier notion of withdrawing from the Rappahannock line to make a stand on the North Anna River.

On the Confederate left, Longstreet was dug behind the town itself, along a rise called Marye’s Heights. Jackson’s men settled on Longstreet’s right south of town, holding a line of higher ground extending south to Hamilton’s Crossing. Named for a local landowner, Hamilton’s Crossing marked the place where the Old Mine Road, which was named for colonial-era iron mines nearby, crossed the tracks of the RF&P. The delayed Union offensive allowed the Confederates ample time to prepare artillery emplacements and dig a formidable assortment of entrenchments and rifle pits.

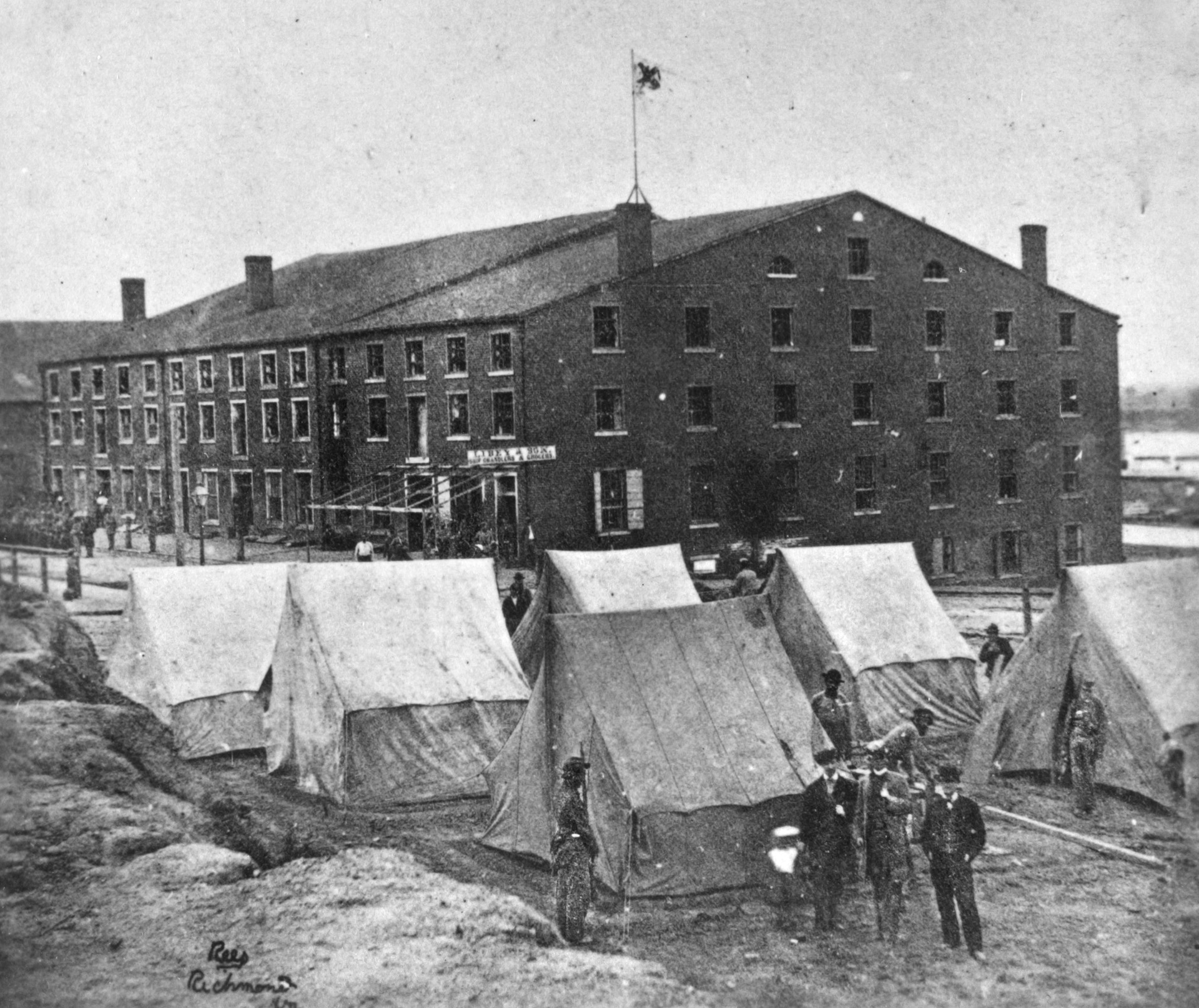

With a population of 5,000 in 1860, Fredericksburg stretched about three blocks deep and one mile broad along the Rappahannock. The town was named for Frederick, Prince of Wales, a member of the British royalty who had died suddenly in 1751. The prince’s eldest son had reigned as King George III. Now an independent city, Fredericksburg was then part of Spotsylvania County.

By the time Burnside had the pontoons available and had committed his army to attack, it was December 10. Upwards of 72,000 Confederates awaited his 100,000-strong Union army. For Sumner’s Grand Division, he placed a pair of pontoon bridges near the northern edge of town, and another one a short distance downstream near the charred ruins of the railroad bridge. Three more bridges eventually were thrown across the river about one mile downstream from the southern edge of town for Franklin’s Grand Division. Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s Reserve Grand Division was in the center, able to reinforce either flank if needed.

Sumner faced stubborn opposition. Confederate guns began shelling Union lines on December 11. Additionally, Rebel infantry peppered the Union engineers as they assembled the pontoon bridges. To stop the harassing fire, Burnside sent a force of Yankees in small boats to gain a foothold on the Rebel side of the river. Fighting block by block, growing numbers of bluecoats pushed deeper into the town.

The I and VI corps of Franklin’s Left Grand Division had a much easier time crossing on the Federal left flank. Engineers set to work on their pontoon bridges before dawn on December 11. The Confederates fired on them after the sun rose, but there were only two companies of the 18th Mississippi on hand. After they’d hit half a dozen of the engineers, Union artillery went into action. The gunners succeeded in scattering the Mississippians. Yankee guns interrupted two more harassing attacks that interfered with the construction of Franklin’s pontoon bridges.

Once the first bridge was complete, Franklin cautiously refrained from crossing until he received Burnside’s permission to do so. Burnside wanted Franklin to wait for Sumner’s troops to secure the upper crossings before allowing Franklin to cross. The army commander finally granted permission for Franklin to cross at 4 pm.

Brig. Gen. Charles Devens brigade of Maj. Gen. William Smith’s VI Corps was the first of Franklin’s units to cross the river. Devens’ five regiments had the responsibility of holding the bridgehead through the night until the rest of the rest of Franklin’s force crossed to the south bank on the morning of December 12.

Franklin’s men stayed close to the river. Smith’s VI Corps went into position on the left Grand Division’s right, while Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds’ I Corps secured the left. Both corps held vulnerable positions, given that enemy troops looked down on them from higher ground. A sluggish stream known as Deep Run, which was opposite a deep curve in the Confederate defenses, would hinder Franklin’s troops from making any movement to their right. For that reason, the only path of retreat open to them was by way of their three pontoon bridges.

Meanwhile, Lee pondered the enemy’s moves. He was still concerned that Burnside might endanger his right with a crossing of the Rappahannock at fords several miles downstream. Lee spread his forces thin, watching the downstream crossings as well as the town and Franklin’s troops. Lee and Jackson, accompanied by staff officer Major Heros von Borcke, rode to a height overlooking Franklin’s troops. Lee made a careful study through his field glasses of Franklin’s deployment. He concluded that Franklin’s two Union corps constituted Burnside’s only move against the Rebel right. With that knowledge in hand, Lee knew he could safely recall forces posted downstream to join to Jackson’s force. These forces included Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s division at Skinker’s Neck and Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill’s division, which had stood guard at Port Royal. They marched to bolster the right wing under Jackson.

Unsure of his next move, Franklin stayed put on December 12. He asked Burnside for permission that afternoon to attack the next day, but the army commander gave no definite orders at their meeting. Burnside did not dispatch his orders for Franklin until almost 6:00 am the morning of December 13. But it took nearly two hours for the staff officer bearing the orders to find Franklin.

Burnside decided to make a two-pronged attack on December 13. Franklin would move against the enemy holding high ground beyond the RF&P, which paralleled the river, before bending sharply south near Hamilton’s Crossing. Meanwhile, Sumner’s II and IX corps would push toward Marye’s Heights.

Burnside did not make clear that he intended Franklin to move first and that he expected him to break through or at least tie up Jackson’s corps before Sumner would move. What is more, the Union headquarters neglected to keep close tabs on the Confederates. “Old Jack” had been heavily reinforced by Confederate troops recalled from blocking positions further downstream. By the time the Federals attacked, the Confederate II Corps had 35,000 men in place behind good cover on high ground.

Jackson’s line stretched for several thousand yards along a forested ridge that sloped down to the railroad tracks. Lee had put his troops to work before the battle constructing a road along which men and supplies could be moved quickly as needed. The new thoroughfare, called the Military Road, was cut through the woods behind the line to ease movement of men and supplies.

Burnside’s orders did not convey a clear sense of urgency. In part, the orders compelled Franklin to “keep your whole command in position for a rapid movement down the old Richmond road, and you will send out at once a division at least to pass below Smithfield, to seize, if possible, the height near Captain Hamilton’s, on this side of the Massaponax [Creek], taking care to keep it well supported and its line of retreat open.”

Franklin believed the orders emphasized the need to seize the Richmond Road, and that the phrase, “send out at once a division at least,” did not mandate that his main priority was to drive Jackson’s corps out of its position on the ridge.

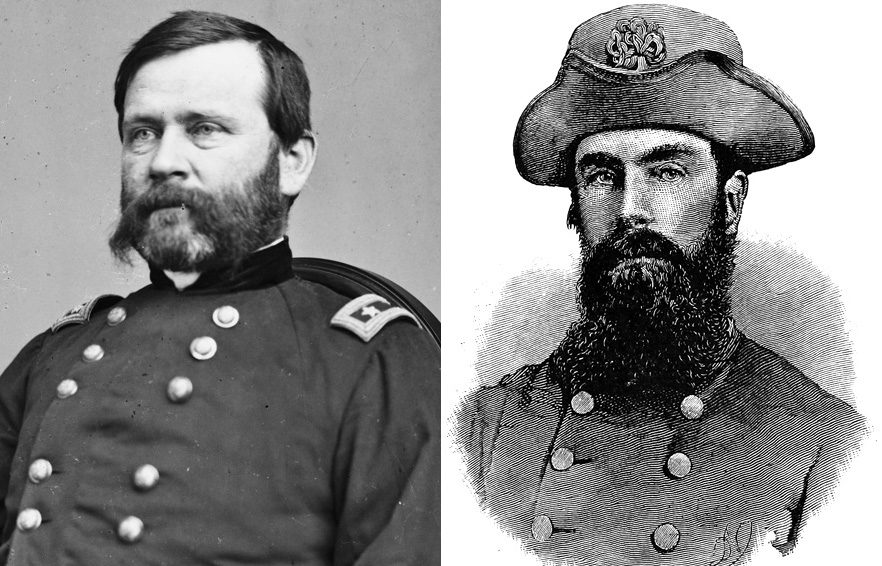

Franklin thought it impractical to take the time to shift Smith’s corps from its position closer to the river to join the attack, so he chose Maj. John F. Reynolds’ VI Corps. Reynolds chose Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade’s 4,500-man division to lead the assault, supported on its right by Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s division. Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday, commanding the reserve, shielded the rear and left of Meade’s troops.

Graduating in the Class of 1835 at West Point, Meade had spent most of his army career as an engineer and had served in the War with Mexico. Although his antebellum years as an engineer gave him little experience commanding combat troops, he rose steadily in command in the first half of the war.

Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtain insisted a few months into the conflict that Meade be given command of one of the three Pennsylvania Reserve brigades. Meade arrived on the Virginia Peninsula in June 1852 and saw heavy fighting in the Seven Days Battle at Mechanicsville, Gaines’ Mill, and Frayser’s Farm. Despite receiving several wounds at Frayser’s Farm, he quickly returned to brigade command. When Lincoln transferred Brig. Gen. John Reynolds, the commander of the Pennsylvania Reserves division, to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to recruit fresh troops to defend the state in case of invasion, Meade ascended to command of the division during the battles of South Mountain and Antietam.

Meade was an intelligent and competent commander, yet he was more cautious than Reynolds. Not always calm and analytical as one might expect of an engineer officer, he possessed an explosive temper that could flare in the heat of battle.

Meade’s division was made up almost entirely of Pennsylvanians. All three of his foot brigades hailed from the Keystone State. His infantry included Colonel Thomas L. Kane’s 13th Pennsylvania Reserves, the famed Bucktails. Skilled riflemen, the regiment’s soldiers carried breech-loading Sharps rifles and adorned their hats with deer tails to symbolize their marksmanship.

Meade also had three batteries of the 1st Pennsylvania Artillery, as well as Battery C of the 5th U.S. Artillery. His cavalry brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. George D. Bayard, included the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry, 2nd and 10th New York Cavalry, and 1st New Jersey Cavalry. The cavalry was supported by Battery C of the 3rd U.S. Artillery.

Daylight on December 13 revealed dense fog shrouding the Union positions on the plain by the river. Lee might have pushed forward, given that the advance of his troops would have been cloaked by the early morning mist. Yet the Rebel commander was satisfied with his defensive lines, and so he opted to sit tight and wait for Burnside to make the first move.

Meade, Doubleday, and Gibbon shuffled their troops in the mist. The 121st Pennsylvania of Colonel William Sinclair’s brigade settled down after the hooting and hollering sparked by the lively chase of a rabbit that bolted through its ranks. The regiment, which belonged to Colonel William Sinclair’s First Brigade of Meade’s division, was ordered to “unsling knapsacks and tear away the hedge in front.” Up and down the Richmond Road, other regiments demolished the hedges lining the roadway. To ease the passage of their artillery, Union troops bridged the ditches on either side of the road.

With Sinclair’s brigade in the lead, Meade’s bluecoats moved out into the thinning mist at 8:30 am. They advanced 300 yards, which took them well past the Richmond Road, and received orders to lie down in an open field. This put the infantry into a position to support Captain Dunbar Ransom’s Battery B, 1st U.S. Artillery.

Major John Pelham, who commanded the five batteries that constituted Stuart’s Horse Artillery, asked permission for a bold move. He wanted to place two guns along the Richmond Road near its junction with Mine Road, from where he could enfilade the enemy line. Stuart consented, and Pelham set off at a gallop with two guns. For the task at hand, he chose a M1857 12-pounder Napoleon smoothbore captured at Seven Pines in June and a British-made Blakely rifle. Pelham took up a position well in front of the Confederate line and opened fire with solid shot.

That morning marked the first time that the new 121st Pennsylvania came under fire. Pelham’s shot was “making deep furrows in the ground and bounding like rubber balls,” wrote regimental historian William Strong. The first man of the 121st to die in battle was cut in half by a cannon ball. Another of Pelham’s shots “struck down seven men, and another killed a horse standing just in front of the colors,” according to Strong.

“The annoying and appalling noise of the flying shells was altogether new and unexpected,” continued Strong. “One gun sent shells whose noise resembled the sudden flight of a great flock of pigeons. A solid shot would land with a thud and rebound to the rear, or come right through the line with the sound of a huge circular saw ripping a log, or pass shrieking through the air in quest of a victim.”

Five Union batteries turned their fire on Pelham. They succeeded in silencing the Blakely rifle. One gunner after another fell, and Pelham himself pitched in to work the Napoleon. When enemy shells landed too close, showing the Yankee gunners had found the proper range, Pelham shifted the gun to a new position and resumed firing. Some of the gunners from one of the batteries in the Stuart Horse Artillery were French-speaking Creoles from Talladega County, Alabama. They were heard singing “The Marseillaise” as they sponged, loaded, and fired.

Stuart sent a courier to suggest that the young major leave his exposed position. “Tell the general I can hold my ground,” replied Pelham. But soon suggestions to withdraw became orders. Pelham brushed off commands to pull back three times. He left his position only when his ammunition had nearly run out. At the cost of a handful of casualties and some dead horses, Pelham had delayed Franklin’s assault on the Jackson’s line by more than an hour.

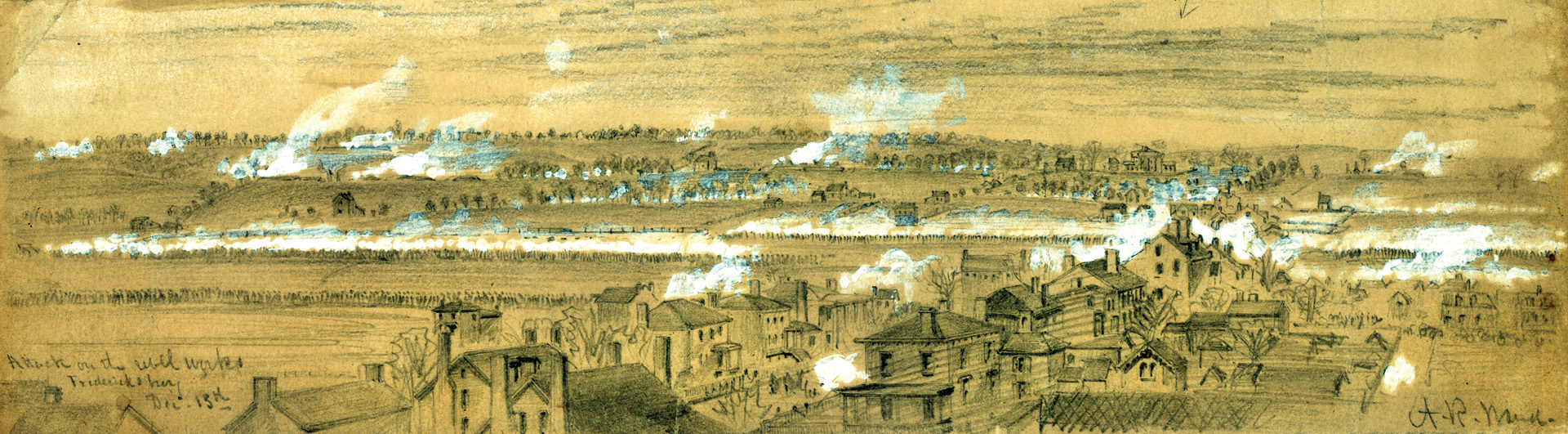

By midmorning the mist lingering over the riverside plain had begun to dissipate. The scene looked as dramatic as “the drawing up of a drop-scene at the opera,” wrote von Borcke. Stuart sent the German aide-de-camp to inform Jackson that the enemy was making their move.

Von Borcke rode to join Jackson on a hill from which the general was scanning the Federal dispositions with a field glass. The lead elements of the Left Grand Division presented “a military panorama, the grandeur of which I had never seen excelled,” wrote von Borcke. “On they came, in beautiful order, as if on parade, a moving forest of steel, their bayonets glistening in the bright sunlight … waving their hundreds of regimental flags, which relieved with warm bits of coloring the dull blue of the columns and the russet tinge of the wintery landscape, while their artillery beyond the river continued the cannonade with unabated fury over their heads.”

Lt. Col. Reuben Lindsay Walker, who commanded the artillery battalion that supported Maj. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill’s Light Division, had assembled atop a rise called Prospect Hill 14 guns from the seven batteries in his battalion. They went into action to the right of Brig. James Archer’s brigade of Hill’s division. Yankee shot and shell crashed amid the Confederate guns. So many battery horses were killed by the artillery bombardment that the Rebels later named the position Dead Horse Hill.

Walker’s guns did not reply to the bluecoat barrage. Their ammunition was limited, and they had orders to hold their fire for the enemy infantry. Only when Sinclair’s brigade approached the railroad embankment and were within 500 yards of their muzzles did the Rebel guns on the ridge opened fire. The Yankees laid down for some time to take cover as the shells from the artillery of both armies flew over them.

A Confederate caisson exploded at 1:00 pm. A plume of smoke rose from the wreckage. Meade chose that moment to order his men to rise up and charge. At last freed from the restraint of waiting under fire, the Pennsylvanians rushed forward.

“A fence crossing the line diagonally of the regiment as it advanced, proved for a few moments quite a serious impediment,” wrote Strong. “Instead of immediately crossing, they allowed themselves to be crowded toward to the left, the fence acting as a wedge to force the men in that direction.” The fence was only a temporary block, and the bluecoats climbed over the fence and “regained their alignment and proceeded on toward the wood,” he wrote.

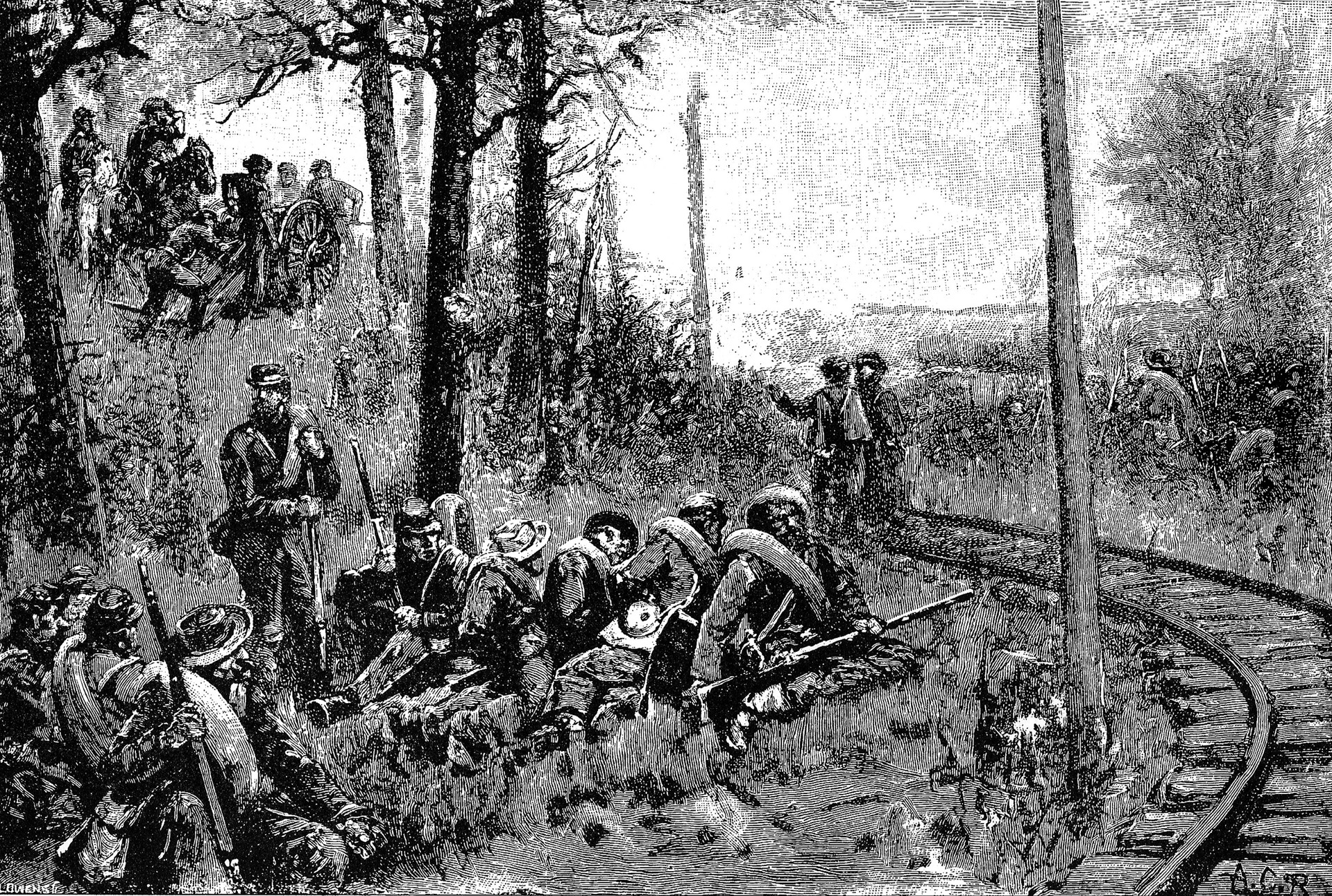

The path before Meade’s Division was for the most part a stretch of flat fields, cut by occasional ditches and small streams that led up to the three-foot-high railroad embankment. Beyond the tracks rose the forested ground offering cover to the Rebels. The Yankees aimed for a small landmark, a patch of trees that jutted out beyond the railroad. The cluster of trees marked a little ravine that passed under the tracks. At that location, just behind the tracks, was a broad and rugged area of marshy ground in a wooded tract.

On the day before the battle, A.P. Hill had examined this area. Believing the swampy stretch as impassible, he assigned no troops to hold it. His decision left a gap of 600 yards between the brigades of Brig. Gen. James H. Lane and Archer. No troops faced that breach in the line other than Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg’s brigade, which was posted 400 yards to the rear along the Military Road that ran along the crest of a low ridge.

The advancing Yankees were unknowingly headed for the only weak link in the Southern line. Even better, the terrain was shaped in a way to create a blind spot for the 53 Confederate guns of Jackson’s corps. Batteries posted on the left of Brig. Gen. William Dorsey Pender’s brigade, near Deep Run, and those clustered on the right around Hamilton’s Crossing could not reach the Yankees as they neared the tracks.

Earlier in their advance, Meade’s Division lost all three of its brigade commanders. When Brig. Gen. C. Feger Jackson was shot dead, command of his brigade devolved to Colonel Joseph Fisher. Sinclair was hit in the left foot and carried off the field. Colonel William McCanless of the 2nd Pennsylvania Reserves did not find out for some time that he was then in command of Sinclair’s brigade. Colonel Albert L. Magilton, the commander of the Second Brigade in Meade’s division, was trapped under this horse, which had collapsed when shot dead during the advance.

After climbing over the three-foot-high railroad embankment, Sinclair’s regiments plunged into the woods, followed by the rest of the division. Expecting deadly enemy fire, the bluecoats were surprised to find the silent woods were empty of enemy defenders. The Pennsylvanians of Sinclair’s Brigade, at that point led by McCanless, wheeled about to surprise Lane’s brigade. Concentrating on their front and expecting no trouble from the swampy woods, the regiments on Lane’s right buckled and fell back.

C. Feger Jackson’s former brigade turned to attack Archer, whose troops were shocked when enemy soldiers appeared out of the impassible woods. More of Meade’s men pushed forward through the woods until they hit Gregg’s line. Some of them had taken cover from the Union artillery. Under Gregg’s orders, they had stacked their muskets lest they shoot any fellow Confederates moving through the woods around their position. Their firearms were out of reach when the Yankees suddenly rushed out and opened fire on Colonel James Orr’s 1st South Carolina Rifles, better known as Orr’s Rifles, which was one of Gregg’s five regiments.

Gregg was hard of hearing. The battle smoke hovering in the brush and saplings around his brigade obscured the cause of the commotion. The general seems to have had the impression that there had been a line of friendly troops posted in his front, and that the men running toward them were retreating Confederates. He ordered Orr’s men and his other troops to hold their fire and rode in front of them to enforce his orders. Then, his spine shot through by a bullet, Gregg fell from his horse mortally wounded. Orr’s Rifles and the Colonel Daniel Hamilton’s 1st South Carolina (Provisional Army) regiment took the brunt of the attack. The two regiments suffered a total of 250 casualties. The 37th North Carolina of Lane’s Brigade turned to meet the attack and held off the Pennsylvanians. Across the gap, Archer’s brigade was harder hit. The regiment anchoring his right flank, the 19th Georgia, collapsed from the blow. Its flag was the only Confederate regimental flag taken at Fredericksburg. As neighboring regiments also began to break, Archer shifted the 5th Alabama from his right to shore up his left. The remaining regiments held in place and Archer’s situation steadied. He sent for help from Gregg, not knowing of the general’s fatal wound and his brigade’s even worse disaster.

Meade’s troops struggled to follow up on their achievements and push through the Confederate line; Gibbon’s forward elements crashed into the front of Lane’s Brigade. A few hours before in mid-morning, Gibbon’s men had advanced toward the Richmond Road until coming under Rebel artillery fire. They lay down to avoid the fire as best they could for three hours.

At 1:30 pm Gibbon ordered the brigades of Brig. Gen. Nelson Taylor and Colonel Peter Lyle to charge the Confederate line. Rather than turn to follow Meade’s men, they went straight ahead for Lane’s brigade. Prepared for a frontal assault, Lane’s men held off the two enemy brigades and threw them back.

Gibbon sent forward Colonel Adrian Root’s brigade 15 minutes later. “Having unslung knapsacks and fixed bayonets, the brigade advance under a severe fire, moving steadily across the plowed field,” wrote Root in his battle report. “[Their advance was] “rendered extremely difficult by several parallel ditches, or rifle-pits, and its rear protected by thick wood, sheltering infantry supports.”

“A veritable laugh passed through the ranks when a piece of shell struck one of the boys’ knapsacks, tore it open and lifted a pack of cards high in the air, intact, when they suddenly spread out and came down like a shower of autumn leaves,” recalled a veteran of the 16th Maine, one of the five regiments in Root’s mixed brigade.

Three other men of the regiment had similar luck. One lieutenant’s life was saved when a tintype in his pocket deflected a musket ball, and another man survived because a Rebel musket ball struck his pocketknife. Corporal Luther Bradford was the first man of his regiment to take a bullet at Fredericksburg. The bullet, which lodged in his hand and remained for two days, was removed to become what he described as a “pleasant’ souvenir” of the battle.

Confederate fire stalled Root’s advance. The front line of his brigade slowed its pace and, without orders, returned the fire. Taylor arrived and with the help of this general and the regimental officers, the brigade moved forward again. “With a shout and a run, the brigade leaped the ditches, charged across the railway, and occupied the wood beyond, driving the enemy from their position,” wrote Root.

When one of the 16th Maine’s soldiers stepped onto the earthworks, a Confederate soldier “sprang up and thrusting the muzzle of his gun full in his face fired it. His face was burned and blackened by the discharge, but otherwise he was uninjured,” wrote Root. He bayoneted the Confederate, who in the chaos of battle had evidently charged his musket but forgot to add the ball.

The charge of Root’s bluecoats struck the center of Lane’s Brigade. This time they broke through and captured 200 prisoners, including the lieutenant colonel and several other officers of the 33rd North Carolina.

Progress soon halted when the Confederates rallied. Nearby brigades lent much-needed support. Brig. Gen. Edward Thomas came to the aid of Lane’s men, while Brig. Gen. Charles Field’s troops came to the assistance of Archer’s brigade. Early, who kept his division in reserve behind Prospect Hill, received an urgent plea from Powell Hill’s staff officer Lieutenant Ham Chamberlain. Chamberlain warned of what he termed an “awful gap” opened by the enemy between Lane and Archer, which threatened to cut off part of the army. Early, commanding one of the divisions in Jackson’s I Corps, sent three brigades to plug the breach.

Meade had achieved the beginning of a breakthrough. In light of the disastrous results of the assaults yet to come against Marye’s Heights a mile or so to the north, the troops of Meade and Gibbon had attained the greatest success of the Union Army at Fredericksburg.

With all three of Meade’s brigadiers out of the action, casualties mounted with their units separated from each other and moving blindly. The famed Pennsylvania Bucktails suffered 161 casualties in the battle. Among the mortally wounded Bucktails was Private Henry Jackson. He was taken to a field hospital after a shell cut one leg off at the knee and smashed the other leg so it required amputation. Jackson was calm, sitting up in bed while the surgeon prepared his instruments. But a shell crashed into the hospital and exploded, wounding the surgeon and killing Jackson and a soldier detailed as a nurse.

On the dearly won wooded slopes of the ridge, Root and Taylor felt their grip on the enemy line sliding away. “The wood was so dense that the connection between Meade’s and his [Gibbon’s] line could not be kept up,” wrote Franklin. “In consequence of this fact, Meade’s line, which was vigorously attacked … could not hold its ground, and was repulsed, leaving the wood at a walk, but not in order.” Quick support was needed. Pouring in additional brigades might have broken the Confederate line and endangered the right flank of Longstreet’s corps and the left flank of Jackson’s corps.

Root rode to ask Gibbon for reinforcements. Gibbon agreed to dispatch reinforcements, but Lyle refused a separate request from Root. Shortly afterwards, Root learned that Gibbon had been wounded and taken from the field. Taylor, who stepped in for Gibbon, told Root to withdraw when circumstances dictated for the safety of his command. Pressed by a resurgent Confederate defense, and with no commanders willing to send support, Root pulled back as far as the Richmond Road. He formed a battle line and threw forward skirmishers, but the Rebels did not pursue his troops.

As the divisions of Meade and Gibbon were pushed back across the railroad, losing the ground they had taken, 20,000 of Franklin’s men stood idle. Meade sent two messages for aid from the division of Brig. Gen. David Birney, of Hooker’s Grand Division. He eventually confronted Birney in person, firing a withering fusillade of profanity at him. Birney was not in Franklin’s division and still balked at sending in his troops without orders from higher up.

When Early’s men cleared the Yankees from the gap between Lane and Archer, they had orders to halt at the railroad tracks. Carried away by their success, Brig. Gen. Robert F. Hoke’s brigade of Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell’s division rushed over the tracks and pursued the scattered Yankee regiments. Franklin finally ordered reserves under Birney and Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles to the front. They were too late to help the survivors of Meade’s and Gibbon’s battered divisions, who streamed back to the Richmond Road. Meade and Reynolds tried to stop them. Meade’s anger pushed him to break his sword when striking a soldier with it. When Birney and Sickles appeared, their belated reinforcements could not restore the earlier Union gains, but they repulsed the Confederate counterattack.

Meade’s assault was over by 2:15 pm. His division was back where they started, with the loss of 4,815 casualties. Jackson’s losses were 3,415 men. This was more than one-tenth of his corps, but he still held his original position and was prepared to resume battle if necessary. Franklin, shocked at his losses, refused Burnside’s orders to send more troops against the Rebel lines.

On the Union right, affairs were even worse. Sumner’s men charged with bayonets against the Confederates at Marye’s Heights. Longstreet’s men had a near-perfect defensive position. Dug deep by years of wagon traffic, the famous Sunken Road was lined with a sturdy stone wall facing the Union advance. Aided by artillery on Marye’s Heights, Confederate infantry standing two ranks deep mowed down the surging waves of bluecoats. To no avail, Hooker threw in his troops after Sumner. Instead of a well-timed mass effort, the troops were thrown piecemeal against Longstreet. None of their charges reached the stone wall. Darkness fell to put an end to the battle.

After confronting Birney and Franklin, Meade reached Reynolds’ headquarters and vented his frustration at the lack of support given his men. “My God, General Reynolds, did they think my division could whip Lee’s whole army?” Meade asked. Meade’s division suffered 1,853 casualties, which was more than one-third of his command. Gibbon, who was himself wounded, had 1,267 killed, wounded, or missing. Doubleday, his division kept in reserve and taking no significant part in the battle, lost only 214.

Lee anticipated a renewal of the battle on December 14, but the battlefield remained mostly quiet. Meade had a close call, though, when a Confederate sharpshooter “took deliberate aim at me, his ball passing through the neck of my horse,” wrote Meade. There was some consolation for the general in that he was riding a substitute horse, and that his favorite mounts named Baldy and Blacky were safe. Both of these horses had recovered from bullet wounds in preceding campaigns.

Overwhelmed by his staggering casualties, Burnside returned his army to the north side of the river on December 15 and encamped at Falmouth. Recriminations flew from Northern newspapers and politicians when the scale of the Union defeat became clear. Approximately 13,000 Union soldiers fell in vain in what was a clear Confederate victory, compared to the roughly 5,000 men lost by Lee.

Little movement occurred around Fredericksburg until January 1863, when torrential rains turned an attempted attack by Burnside into the futile, and quickly cancelled, Mud March. Lincoln replaced Burnside with Hooker, who in turn would last no longer than the next Union debacle, which unfolded 10 miles to the west at Chancellorsville the first week in May 1863.

At Chancellorsville, Meade had been promoted to command of the V Corps. Remembered for achieving the Union’s greatest success at Fredericksburg, he burnished his credentials at Chancellorsville. When Lincoln fired Hooker, he ordered Meade to take command of the Army of the Potomac. Just two days after Meade accepted command of the Army of the Potomac, the Battle of Gettysburg began on July 1, 1863. Meade would forever be remembered afterwards for defeating Lee’s second invasion of the North.