By Glenn Barnett

The Spanish-American War saw the development of the torpedo as we know it today. It was not the static mine of the Civil War but a propeller driven, waterborne explosive device. Small, fast torpedo boats were designed to carry and launch torpedoes against capital ships. The centuries old dominance of big guns on big ships was threatened.

As a defensive response to this new offensive threat, the world’s navies came up with a class of small ships that were originally named Torpedo Boat Destroyers. They were big enough to sail with the blue water fleet and fast enough to foil the torpedo boats. Very soon these little ships took on multiple roles and their name was shortened to Destroyer. Ironically, for many years they themselves also carried torpedoes.

In the United States, several small batches of three to six destroyers were built, each incorporating improvements in armament, speed, and size. With the outbreak of World War I, two classes of these new ships were built in quantity. There were 110 of the Wickes Class built, followed by 156 of the Clemson Class.

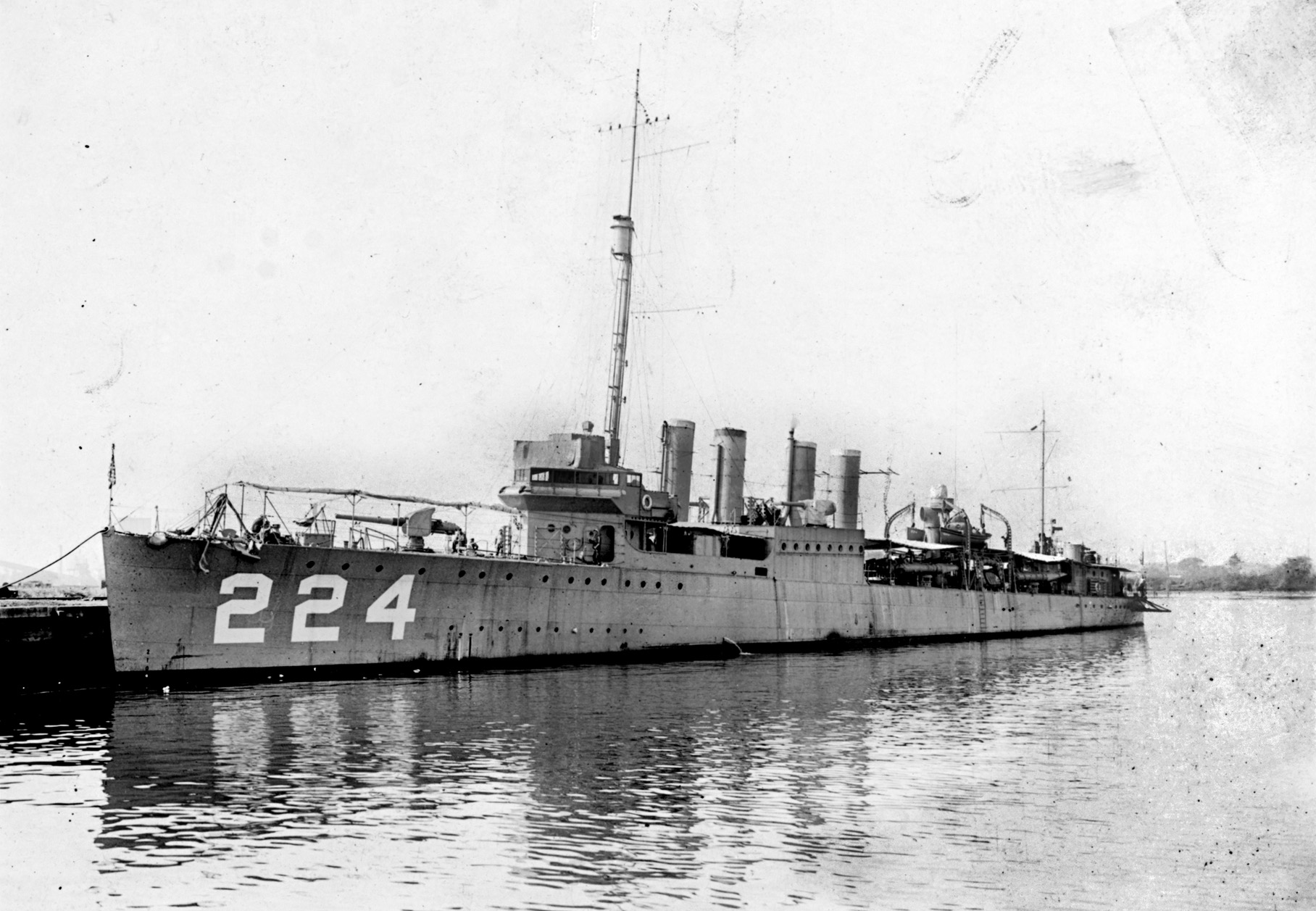

These two classes of ships were distinguished by their flush decks, which meant the entire deck was at the same level, eliminating the forecastle. They were also known as four-stackers, meaning they each had four distinctive exhaust funnels. One of these Clemson-class ships was the USS Stewart (DD-224). For Stewart, the experience of the next war would be different than that of any other oceangoing American warship.

Stewart started life at the William Cramp & Sons construction yards in Philadelphia and was launched in March 1920. She displaced 1,100 tons and was 314 feet long with a top speed of 35 knots. Her armament consisted of four of the standard 4-inch (102mm) guns, one 3-inch (76mm) gun and dozen 21-inch (533mm) torpedo tubes.

After the Great War, there wasn’t much for all those destroyers to do. Many were mothballed only to be brought out of retirement when World War II started. Fifty of them were loaned to Great Britain through the Lend-Lease program. But Stewart stayed in service throughout the interwar years, assigned to the Asiatic Fleet in 1922. In this role she visited Chinese ports such as Tsingtao (Qingdao) in the summer and returned to the warmer climate of Manila in winter.

By 1932, the Japanese became increasingly interested in China and the Americans found themselves in the middle of a new war. Stewart had to protect American interests and citizens from pressure coming from both sides. As the decade progressed, the American (and Western) presence in China was increasingly threatened by aggressive Japanese expansion.

In September 1939, with war breaking out in Europe, Stewart was ordered out of China to Manila, where she took up patrol duties and stood out to sea as a guard for seaplanes flying to and from Guam and the Philippines. She made one more trip to China in the fall of 1940, but it was her last before the war. On November 27, 1941, in an atmosphere thick with rumors of war, Stewart and other naval assets were ordered from Manila to the Dutch East Indies for their own safety.

However, the East Indies would not be safe for long. On December 8 (in their time zone), the American and Allied vessels moored at the Dutch Port of Tarakan, an important oil facility in Borneo, received a rude awakening. A terse message read, “Japan started hostilities; govern yourselves accordingly.” It was, of course, news of the attack on Pearl Harbor. For the rest of December the destroyer, now on a wartime footing, was charged with escorting naval auxiliary vessels from the doomed Philippines to Darwin, Australia.

In the second week of January 1942, Stewart with four other destroyers and the light cruisers Boise and Marblehead departed Darwin to escort the Dutch transport ship M.S. Bloemfontein and American transports Chaumont and Holbrook in the waters of the Torres Strait, the narrowest passage between Australia and New Guinea. These ships had arrived in Brisbane on December 22 with the Pensacola Convoy, which was diverted from its original destination, the Philippines, when war broke out. Now Bloemfontein’s cargo of 48 (75mm) field artillery pieces and their artillerymen, unable to reach Manila, were slated for Java to assist the Dutch in defending the island against the onrushing Japanese.

At the end of January, Stewart joined the cruiser Marblehead and ships from Australia and Holland in patrolling the Makassar Strait between Borneo and the island of Sulawesi (Celebes). This was the last open link for ships fleeing the nearly surrounded Philippines and for Allied ships to strike at Japanese transports.

The Allied flotilla was spotted by Japanese scout planes, and bombers were dispatched against them. In the ensuing action, Marblehead was damaged and Stewart escorted her slow retreat to the Dutch port of Tjilatjap (Cilacap) in southern Java. The aging cruiser had taken on too much water to glide over the shallow sandbar into port and had to steam, cautiously in her derelict condition, all the way to New York to undergo repairs.

Stewart was then assigned to the coalition of Allied naval assets known as the American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command under Dutch Admiral Karel Doorman. The ships of the four nations had issues of commonality in communication, language, traditions, fleet maneuvers, and assumptions about each other and no time to sort things out.

The Allied ships, mainly aging cruisers and destroyers, were not yet assembled when the Japanese invaded Bali on February 19, 1942. In response, Doorman sent his ships piecemeal to the attack. In the ensuing Battle of Badung Strait, the Allies sought to destroy the Japanese landing transports and their escorts. The combined Allied fleet was superior in numbers and firepower to the Japanese force, but since they did not combine before they attacked, the Japanese were able to defeat each of the two separate columns in turn. Stewart led the second attack, three hours after the first one had failed.

In the confused night action, at which the Japanese excelled at this time of the war, Stewart was hit several times, mangling her torpedo tubes and splintering her boats. Worse, she was hit below the waterline aft, and the sea poured into her steering engine room. Even though that room was flooded with two feet of water, she still answered her helm and maintained station until the battle was over.

The next morning, she limped into the port at Surabaya in eastern Java for repair. On February 22, she was hurriedly moved into the port’s 15,000-ton floating dry dock. Local dock workers placed supporting blocks underneath her keel, but their work proved inadequate.

Even while in dry dock many of Stewart’s crew were aboard in their bunks while the captain, Lieutenant Commander Harold Smith, and his staff were meeting in the wardroom. When the dry dock was lifted and the ship began to rise out of the water, the supports gave way, dropping Stewart at a 37-degree angle on her port side in the 12 feet of water that remained in the dry dock. One propeller shaft was severely bent, and the hull was further compromised. As she rolled, her officers were thrown across the wardroom and the crew below were hurled from their bunks. Everyone scrambled to get out, and fortunately no one was hurt.

After a quick assessment it was estimated that repairs would take at least three weeks, time they did not have. To add insult to injury, a Japanese bomber hit Stewart amidships causing more damage. There was no time to get her upright, pump out the water and spilled oil, bang and weld her leaky hull, and get her underway on one propeller to Australia. Stewart was abandoned and struck from the Navy list of active ships. Her crew was broken up and sent to join the crews of the remaining American destroyers on the Java station, Parrott, Pillsbury, and Edwards.

Port authorities set off demolition charges within the ship, and the dry dock itself was scuttled before the Dutch abandoned Surabaya on March 2. The Japanese moved in the next week. They found Stewart still on her side with much of the ship under water. There she sat while the occupiers tended to the more important work of getting oil out of the ground and into tankers bound for home.

Finally, almost a year later in February 1943, the Japanese raised the submerged dry dock along with the unfortunate destroyer. The newly refurbished dry dock became known as No. 102 Naval Construction Department. A navy contractor named Lieutenant Fukui Shizuo began work on the great number of repairs needed to restore Stewart and make her seaworthy. Shizuo switched out her guns, with two captured Dutch Army 75mm antiaircraft guns, two 12.7mm antiaircraft guns, and two Japanese 3rd Year Type 6.5mm machine guns. He also mounted a Type 94 depth charge thrower and Type 2 Mk depth charge rails along with 72 depth charges. Type 93 sonar was added. In addition, Stewart’s two forward funnels were combined into one as in other Japanese ships.

On September 20, Stewart was commissioned into the Japanese Navy and renamed IJN Patrol Boat 102 (PB-102). Japanese destroyers of the time were much larger and more heavily armed than their Western counterparts, so Stewart was demoted to a patrol boat.

In early September, she was thoroughly cleaned and fumigated before a crew was assembled. She then underwent sea and weapons trials. In mid-October, she weighed anchor in Surabaya bound for Balikpapan, Borneo, while escorting the oil tankers Kenyo Maru and Nichiei Maru. On her first voyage, lookouts spotted a periscope, and PB-102 dropped depth charges in response. For the rest of the year, she escorted tanker convoys and performed anti-submarine sweeps between Borneo and the heavily fortified island of Truk (now Chuuk).

On March 9, 1944, the crew had a scare from a submarine attack. One torpedo missed the ship by 65 feet astern, and another struck her port side with a great thud but did not explode. An inspection revealed no damage. On March 22, PB-102 evaded two more submarine launched torpedoes.

On May 6, while she was escorting a troop convoy from Manila through the North Celebes Sea, the American submarine USS Gurnard (SS-254) sank three of the transports, Tajima Maru, Aden Maru, and Amatsusan Maru, which was initially set ablaze but remained afloat. Gurnard was forced under and withstood a depth charge attack numbering nearly 100 charges, some of them from PB-102, but survived to find Amatsusan Maru making little headway. She was sunk with another torpedo. Altogether there was great loss of life. For the rest of May, PB-102 was beset with persistent boiler problems and retired to Cavite in Manila Bay for repair. In June, she continued convoy duty. However, boiler problems persisted throughout the war. She was no longer able to reach her designated speed.

By this time, long-range American reconnaissance planes had observed a flush deck Japanese warship. Though the ship had three funnels instead of four, and no other Japanese warship had a flush deck and other distinctly American features. It was a puzzle for a time.

In the moonlight of the predawn hours of August 24, American submarines Harder (SS-257) and Hake (SS-256) moved into Dasol Bay, north of Manila, where their periscopes were spotted. Lieutenant Commander Frank E. Haylor, the captain of Hake, misidentified the two vessels that were steaming toward them. One of them was PB-102, which he mistook for a Siamese destroyer with three stacks, the Phra Ruang. The other ship, also misidentified, was the anti-submarine escort ship CD-22, which was thought to be a minelayer.

While PB-102 turned back into the harbor to protect shipping there, CD-22 attacked and sank Harder with all hands. Hake escaped. Harder had been one of the most successful American submarines scoring 20 ½ victories on her six patrols. Her daring captain, Commander Samuel Dealey, would be the posthumous recipient of the Medal of Honor.

On August 30 and September 1, PB-102 brought in a convoy to Takao, Taiwan, as the harbor twice came under American bombing attacks. All of PB-102’s guns blazed away at the attackers, but no success was claimed.

In mid-September, PB-102 was dry docked at Muko Jima, near Kure, for repair and refit. Her funnels were lowered, and more ballast was added to give her a lower profile in the water, even though it further slowed her speed. Her aging Dutch guns were traded for Japanese made 80mm (3.1-inch) antiaircraft guns fore and aft. Twelve Type 96 25mm antiaircraft guns were also added along with 72 new depth charges, updated radar, and sonar.

One of the aging and leaking boilers was reworked. Three of the four boilers were now working, bringing her best speed to 26 knots. On October 18, she took up her duties again as an escort, this time protecting a large convoy to Foochow (Fuzhou), China. She then plied the waters between Taiwan and the Philippines, escorting convoys and damaged ships which lagged behind.

On November 25, 1944, in the Luzon Strait, the submarine USS Atule (SS-403) fired a spread of six bow torpedoes and two from her stern tubes. Two of the ships in PB-102’s convoy were hit. One, Patrol Boat 38, exploded and sank instantly while Manju Maru slowed to a dead stop and sank by the stern. Estimates were that 700 of the 1300 military passengers on board (including survivors of the sunken battleship Musashi) were killed either in the initial explosion or by drowning. PB-102 could do little.

Things got worse. On December 3, while PB-102 escorted a convoy from Taiwan to Singapore, torpedoes from USS Pampanito (SS-383) damaged Seishin Maru. Later that same day, USS Pipefish (SS-388) sank another ship. The convoy scattered, and the surviving ships individually headed for the nearby island of Hainan.

PB-102 continued her endless round of escort duties and occasional patchwork repair into 1945. Then on April 27 at 2234 hours, her sonar operator picked up an incoming aerial contact. PB-102 changed course, placing herself between the aerial intruder and the convoy. She was set upon by two Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats attacking at low level. PB-102’s gunners shot down one of them making an overconfident approach. The other PBY dropped its bombs, which missed, and then strafed her decks before departing.

PB-102’s hull was riddled by bomb fragments from a near miss and machine-gun fire, opening nearly 100 small holes in her thin hull. Her surface-search radar antenna was damaged, and a rudder cable snapped temporarily putting steering out of action. At 2300, she was attacked by another PBY, followed by yet another attack at 2307. Only the late hour and darkness saved her. The next day, with her steering under control, PB-102 fended off more air attacks against her convoy and finally arrived in port at Moji in Japan.

In late August 1945 the patrol boat was docked at Hiro Bay east of Kure with a reduced crew. That is where PB-102 was discovered and inspected by three U.S. naval officers. The hard-used ship was found to be rat infested and in poor condition. The Japanese crew and dock workers were ordered to thoroughly clean, fumigate, and paint the ship. The Americans hoisted their flag, once again, aboard their lost destroyer.

On October 29, she was boarded by an American prize crew, and the next day she was recommissioned in the U.S. Navy simply as DD-224, since another destroyer was given the name Stewart (DE-238) when DD-224 was presumed lost on Java. Stewart (DD-238), survives today on display in the port of Galveston, Texas.

DD-224 soon left for home, but her engines, constantly busy since 1920, failed and she had to be towed. She entered San Francisco Bay on March 26, 1946. There she was removed from the Navy list and decommissioned.

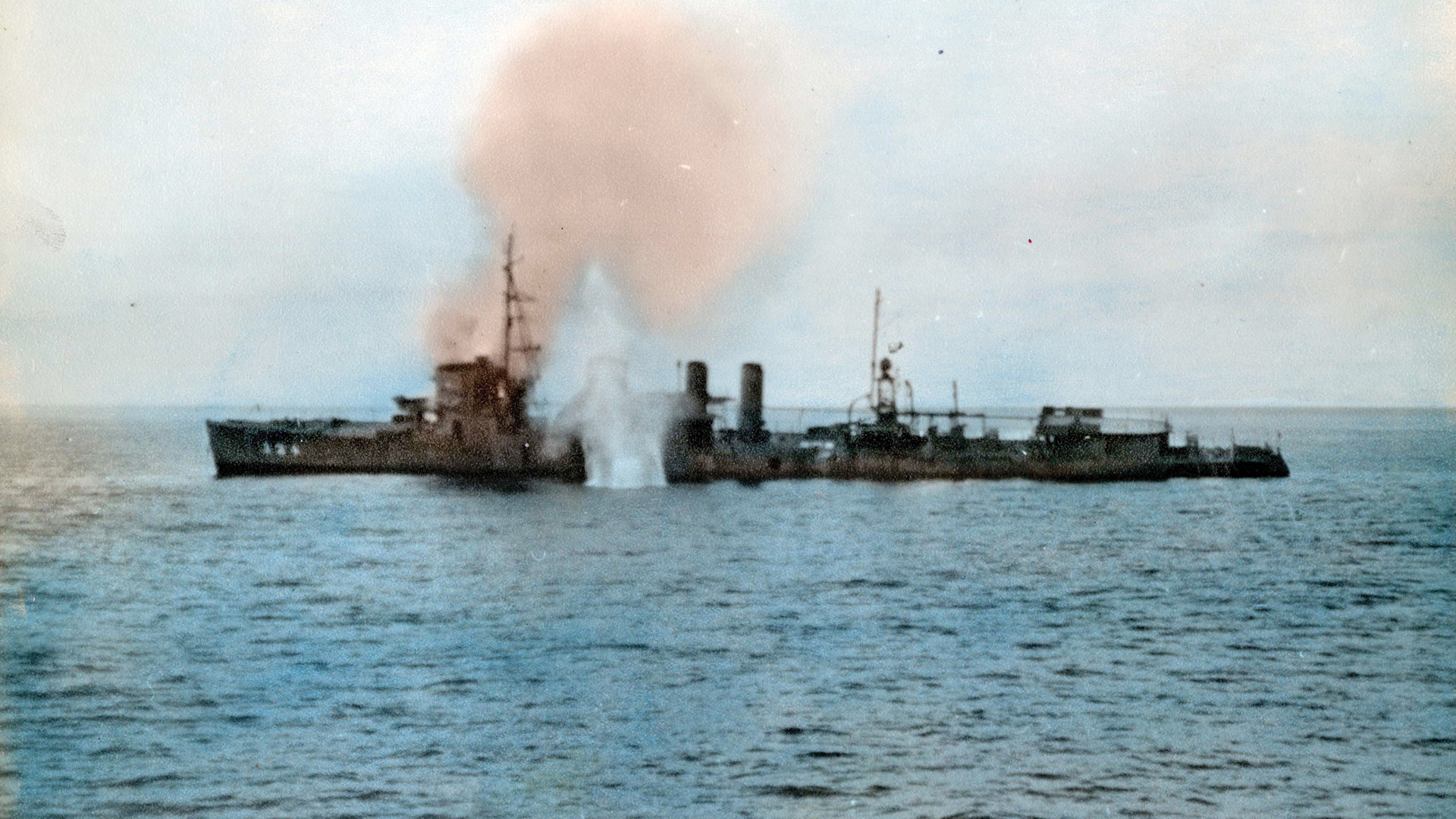

Finally on May 24, 1946, ex-Stewart (DD-224) was towed out to sea and used as a target ship by rocket firing Vought F4U Corsair and Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter planes, which sank her, ending one of the most unique chapters in American and Japanese naval history.