By John W. Osborn, Jr.

ONE of World War II’s least known campaigns was fought over one of the most desolate places on earth. For a few August days it was Britain’s only battlefield, apart from the very sky above it. Yet it produced one of the war’s most unique victories, and its only land victory for Fascist Italy.

“Six feet up the Empire’s geographical orifice,” a colonial official unlucky to find himself there called those 68,000 square miles dismally, drearily dumped on the southern entrance to the Red Sea, 200 miles across the Gulf of Aden. But it was precisely that strategic location along the route to India that led the British to bother signing treaties of protection with the tribes there between 1884 and 1886.

Even for them the area “is hard to love,” the only author to bother writing about the British presence there commented. “Six inches of rain makes an abundant year, and as little as two paltry inches are possible.” It had absolutely no natural resources or industry of any kind, and on the outbreak of war in 1939 the European population of the capital and port, Berbera, stood at only 100.

The British in Somaliland at the outbreak of World War II faced Fascist Italy along a 750-mile border with Italian Somaliland, Eritrea, and recently conquered Ethiopia, with no more to defend themselves than the Somali Camel Corps under Lieutenant Colonel Reginald Chater, Captain Eric Charles Twelves Wilson, a dozen other British officers, 400 men, and 150 reservists. The persistent, petty, pence-pinching of peacetime for the protectorate perilously persisted when Chater’s appeal for 12,000 to 15,000 pounds to improve defenses at first got him only 900 pounds.

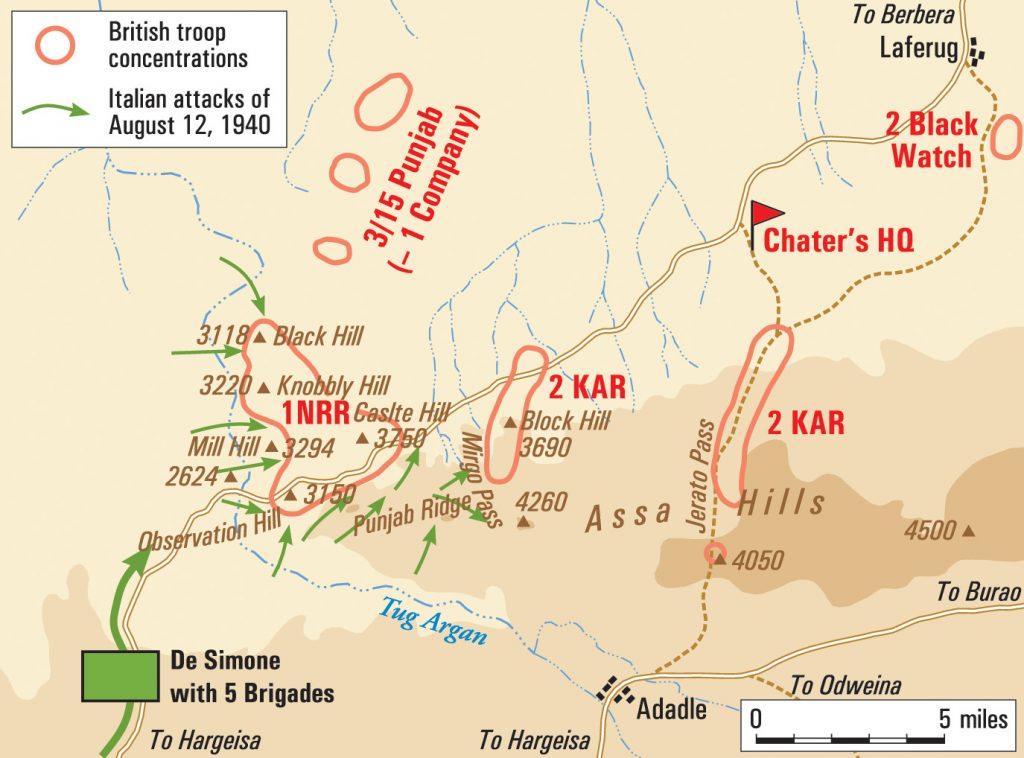

In December 1939, the Imperial Chiefs of Staff began gradually sending reinforcements, including the 1st Battalion, Northern Rhodesia Regiment; 2nd Battalion, King’s African Rifles; 1st East African Light Battery; 1st Battalion, 2nd Punjab Regiment from across the Gulf in Aden, and finally the 2nd Battalion, Black Watch. A defensive line was constructed along the Tug Argan Gap, the gateway into British Somaliland, 50 miles south from Berbera.

But the multi-racial force was a nightmare to supply, was short on artillery, transport, and signal equipment, lacked a proper headquarters, and was desperately dependent on air cover from 200 miles across the Gulf in Aden. Authorities there also had their own priorities. Berbera completely lacked facilities as a port, and even in peacetime a ship usually needed 10 days to unload.

In January 1940, British Somaliland came under Middle East Command led by General Sir Archibald Wavell. He visited the area, inspected the defenses, conferred with the French in their sad slice of Somaliland (present-day Djibouti) about common defense, and decided, in the event of an invasion, to put the British under joint command of the French.

Wavell’s 7,500 personnel were outnumbered by the Italians, who were massing five times their number in Blackshirt battalions and Shoan, Amharan, and Eritrean conscripted collaborators. The situation worsened just two months later with the fall of France.

The French withdrew their forces from their border positions, and Wavell lamented, “The collapse of French resistance released the whole of the Italian Eastern Army for operations against British Somaliland…. I had to decide whether to evacuate British Somaliland forthwith or to continue to hold it.”

After conferring by cable with Chater, he came to his decision. “I decided,” Wavell wrote, “to continue to defend the approaches to Berbera for as long as possible. Brigadier Chater reported that if the force was increased to five battalions he considered that there was a good prospect of holding his positions; also withdrawal without fighting at all would, I considered, be more damaging to our prestige than withdrawal after attack.”

Another high-ranking officer was quite pessimistic, noting, “The overrunning of Somaliland seems assured…. Poor Reggie Chater, he deserves a better show but he’s a fine soldier and will hold them up for a time. I only hope there isn’t a second Dunkirk in the Red Sea.”

British air reconnaissance reported the first Italians to cross the frontier in a three-pronged invasion on August 4, 1940, under Lieutenant General Carlo de Simone, who led the central and primary force, driving north for Berbera.

Resistance by the Camel Corps and the Rhodesians as well as an unexpected rain stopped the Italians. Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was thoroughly irritated: “Mussolini is very resentful toward the Duke of Aosta (Viceroy of Italian East Africa) because of the delay in operations in Somaliland,” the dictator’s son-in-law and Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano confided in his diary. “He repeats the formula, ‘Princes ought to be enlisted as civilians.'”

Mussolini soon ordered his forces to “pour all available reserves into Somaliland to stimulate the operation.” However, there would be no need as de Simone, after two days’ delay, resumed his advance straight to the campaign’s main event, the Battle of the Tug Argan Gap, August 11-15, 1940.

“Tug Argan Gap, through which runs the main Hargeisa-Berbera Road, is some 8,000 yards in width,” Wavell wrote. “It is flanked on the north-west by a succession of flat-top hills with numerous sandy ‘tugs’ (‘tug’ is the local name for wadi or ravine) separating them; and on the south-east by a range of hills varying from 600 to 1,500 feet above the floor of the gap. The country in the gap itself is fairly flat, sparsely covered with thorn bush and invested with fairly numerous tugs of all sizes running in a south to north direction. The Tug Argan itself is a large sandy riverbed some 150 yards in width and running south to north; it was on the southwest or enemy side of all our defended localities.”

Among the defenses, Observation Hill, to the left of the road for Berbera, was the strongest position. The weakest, its defenses unfinished, was Mill Hill on the right. Knobbly Hill sat a mile west of the gap, Black Hill one and one-half miles further south covering the right flank, and two others, Castle and King, to the gap’s rear. The hills, however, were too far apart to provide mutual support, and they were woefully undermanned. The Italians would, therefore, have little trouble infiltrating between the positions.

The British were alerted to the Italian advance by the headlights of the invaders’ vehicles in the distance and by Somali refugees. The battle opened with a 7:30 am air attack followed by an artillery barrage until noon, and then finally the first ground assault at 12:30 pm. The fighting ebbed and flowed for four days, at times hand to hand.

Twenty-seven year old Captain Eric Charles Twelves Wilson was in the thick of the fighting. Graduating from the Royal Military College, Sandhurst in 1933, Wilson sought service in Somalia, transferring from the famed King’s African Rifles to the Somali Camel Corps in 1939. He was tasked to organize a 75-man machine-gun company, which he now commanded on Observation Hill.

“The enemy attacked Observation Hill on August 11, 1940,” an official report related. “Captain Wilson and Somali gunners under his command beat off the attack and opened fire on the enemy troops attacking Mill Hill, another post within his range. He inflicted such casualties that the enemy, determined to put his guns out of action, brought up a pack battery to within several hundred yards, and scored two direct hits through the loopholes of his defenses, which, bursting within the post, wounded Captain Wilson severely in the right shoulder and in the left eye, several of his team also being wounded. His guns were blown off their stands, but he repaired and replaced them and regardless of his wounds carried on whilst his Somali Sergeant was killed beside him.”

Wavell related, “On 12th August the enemy’s attack developed in full force, each defended locality was attacked by large forces of infantry, supported by artillery…. The enemy came on with great determination and undoubtedly suffered extremely heavy losses.” Holding the weakest position, Mill Hill, the East African Light Artillery fired 1,000 shells from their 37 mm howitzers straight down over open sights. They were down to their last seven shells when Mill Hill was overrun at 4:00 pm, and the East Africans escaped.

“On August 12 and 14,” the official report continued, “the enemy again concentrated artillery fire on Captain Wilson’s guns, but he continued, with his wounds untended, to man them.”

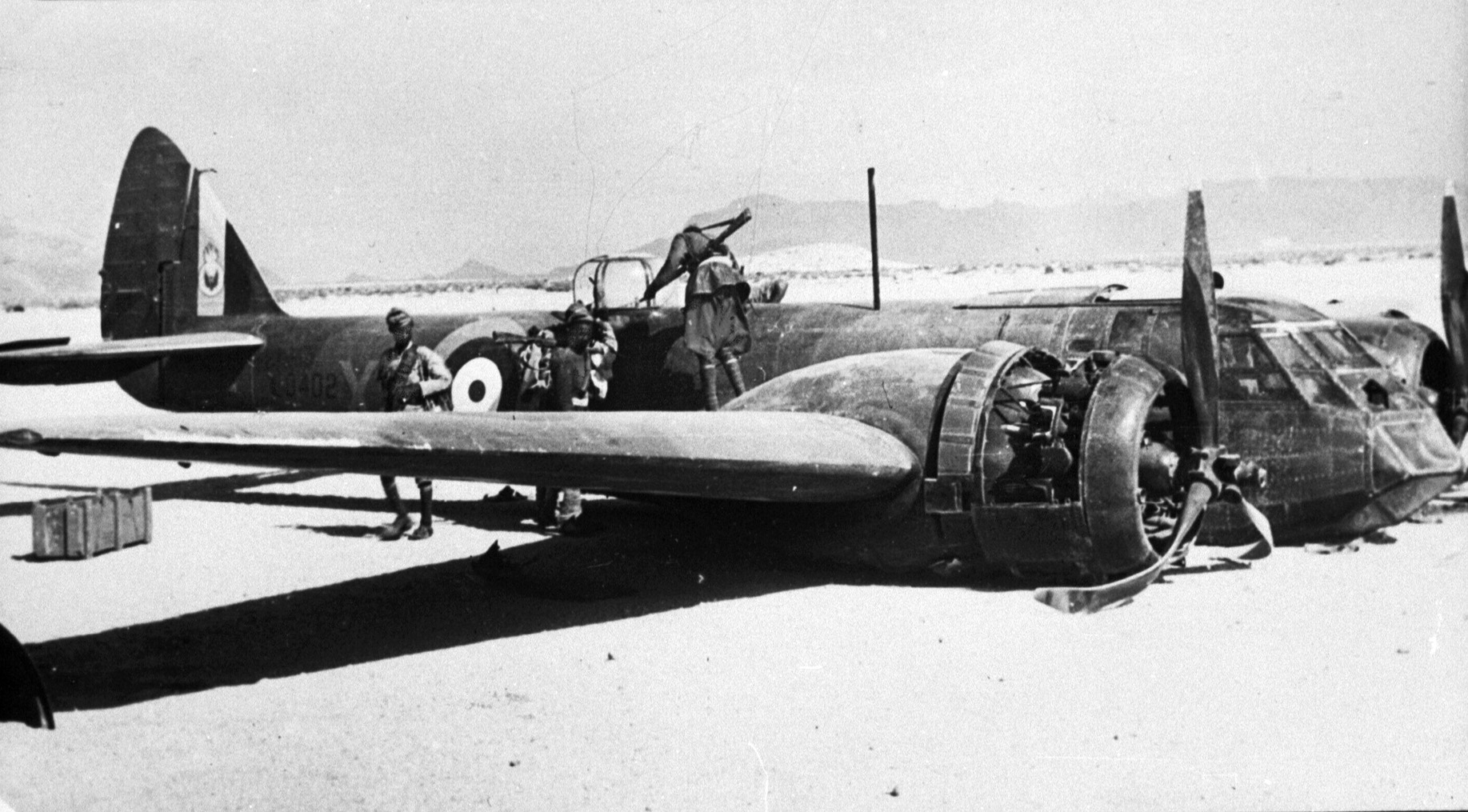

Meanwhile, the battle in the air was no less intense. “The oil barrels catch fire like matches, sending dense columns of smoke up. What a brutal joy one finds in destruction!” an Italian airman declared. Royal Air Force pilots flew 184 sorties across the Gulf from Aden in outdated Gloster Gladiators, Bristol Blenheims, and Fairey Battles, dropping 60 tons of bombs, losing seven aircraft with 10 others damaged, a dozen crew killed, and three wounded. The Italians lost three aircraft.

A badly needed supply column from Berbera with ammunition and water was ambushed by the Italians. Mirgo Pass, east of the Gap, fell, opening the road to Berbera for the Italians. On the 14th, 500 Italian shells slammed into Castle Hill. Italian air attacks were constant. Then the Italians launched their all-out assault at the key to the defense line, Observation Hill, and Captain Eric Charles Twelves Wilson.

“On August 15th, two of his machine-guns were blown to pieces, yet Captain Wilson, now suffering from malaria still kept his own post in action,” the report related. “The enemy finally over-ran the post at 5:00 pm on the 15th of August when Captain Wilson, fighting to the last, was killed.”

For his extraordinary heroism, Wilson received a posthumous Victoria Cross, announced on October 11, 1940. His stand was likened in Great Britain to Rourke’s Drift against the Zulus in 1879. But an East African had his own, grimmer, assessment of the action at Tug Argan Gap: “All finished, no good.”

Major General Alfred Reade Godwin-Austen, rushed from Palestine to assume command the day of the Battle of Tug Argan Gap started, regarded the situation as no poor reflection on Reginald Chater, believing that Chater was too junior for such a suddenly expanded command. Godwin-Austen’s orders to hold British Somaliland allowed him to “take the necessary steps for withdrawal,” and he did.

The Black Watch had landed in British Somaliland just two weeks before, and a company sent up as reinforcements was ambushed in the night of August 14 and scattered in confusion. With Mirgo Pass in Italian hands and in position to cut the road to Berbera and isolate the remaining British in Tug Argan Gap, Godwin-Austen cabled Middle East Command in Cairo in the early hours of August 15 to request evacuation from British Somaliland as “the only course to save us from disastrous defeat and annihilation.”

The invasion had caught Wavell in London for meetings with Churchill and the chiefs of staff, and it fell to his deputy, General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, to decide.

Wilson promptly replied, “Permission granted.” He cabled Wavell in London, “Enemy broken through Tug Argan Pass with hopelessly superior forces and firepower. Restoration of situation impossible. Have sanctioned evacuation. Hope to save 70 percent of force.”

Wavell answered two hours later, “Evacuation of Somaliland is accepted and there is no recrimination as to events there.” Consequences were to come later and rock Whitehall. “When I brought (Churchill) the news of the evacuation,” Wavell recalled, “I rather expected an outburst. But he took it very well.” Unfortunately for Wavell and Godwin-Austen, the prime minister’s perspective later changed.

The British booby trapped their positions around Tug Argan Gap and pulled out that night. Given a chance to redeem itself, the Black Watch fought all the next day at Barkasan Hill, just 15 miles from Berbera, to cover the evacuation from there to the Red Sea. With only a Bofors gun and a captured Breda gun and just five rounds between them, a Black Watch sergeant knocked out three Italian armored vehicles. Italian officers used whistles to direct their Eritreans until the Black Watch’s official historian would later write, “The whole countryside was an elaborate whistle symphony.”

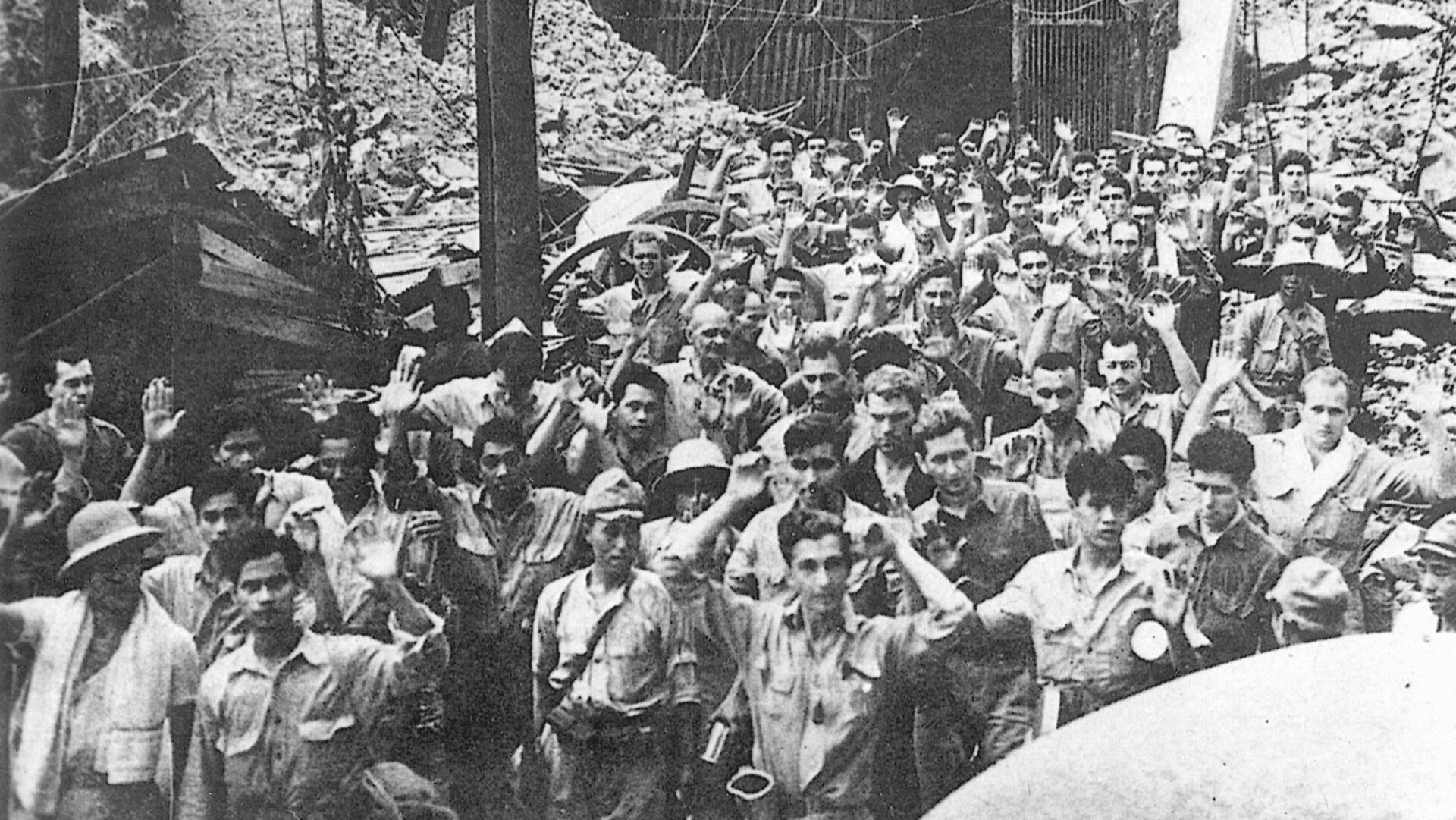

Fifty Black Watchers counter-charged with bayonets, yelling across 600 yards to send the Eritreans, in their official historian’s words, “like hares in their hundreds.” Soon the Black Watch received the order to fall back on Berbera, where the Royal Navy had constructed an improvised jetty. The evacuation of civilians and soldiers took place like clockwork despite Italian air raids. The last British troops departed at 2:00 pm, August 18, 1940.

“The local Somalis of the Camel Corps were given the option of evacuation to Aden or disbandment. The great majority preferred to remain in the country. They were allowed to retain their arms,” wrote Wavell.

When Oscar Brooke, a captain in the Corps, told his Somali sergeant that the company was to be disbanded, the Somali asked anxiously, “And England? What was to happen to England?” Brook assured him that everything was all right there. “Oh well,” the sergeant replied, relieved, “if England is all right, everything will be all right.”

The slow-moving Italians entered Berbera two days later. Still Fascists, they exalted in what would be their only victorious campaign of World War II, one proclaiming, “Victory is our cry! We set off like arrows from the bow.” Beside the perverse Fascist pride, the victory promised, as well, the practical use of British Somaliland to attack shipping in the Red Sea and threaten the line of communication through the Suez Canal to India and the Far East.

Publicly Churchill dismissed the loss of British Somaliland as “a small but vexatious military episode.” Privately, though, he asserted, “I was far from satisfied with the tactical conduct of this affair which remains our only defeat at Italian hands. At this particular moment, when formidable events impended in Egypt and when so much depended on our prestige, the rebuff caused injury far beyond its strategic scale.”

Churchill particularly pointedly questioned whether the British losses, 39 killed, 120 wounded, and 120 missing, had demonstrated much effort. He would have had a better idea had he known of the Italian losses: 465 killed, 1,530 wounded, and 34 missing. Instead, Churchill sent off a cable that was “red hot,” as an aide described it. Wavell was its recipient in Cairo, and Churchill demanded an inquiry and Godwin-Austen’s suspension.

Wavell blamed the defeat squarely on “our insistence on running our Colonies on the cheap, especially in matters of defense.” He criticized the government’s delay in deciding to defend British Somaliland, denounced the French, and finally dismissed Churchill’s demands. “A big butcher’s bill is not necessarily evidence of good tactics,” Wavell followed. The Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir John Dill, recalled that the observation had “raised Winston to greater anger than I had ever seen in him before,” and a confidante commented, “Winston raged, but could think of nothing to say.”

For Wavell, it was the start of the steady slide in their relationship that ended with Wavell militarily marooned from the war in the prestigious position of Viceroy of India. Godwin-Austen joined Wavell in operational exile as Quartermaster of India. There was a feeling of injustice surrounding Churchill’s treatment of Godwin-Austen, and he was retired as a full general in 1947. Reginald Chater alone came out without blame; promoted to major general, he later served as Director of Combined Operations for India and South Asia.

The Italians would have little time to enjoy their success. On March 16, 1941, as part of the general British offensive against the Italians across East Africa, a quartet of Royal Navy ships appeared off Berbera, shelled it, then landed a pair of Sikh battalions.

They met no opposition. “The enemy garrison of a brigade had melted away. All of British Somaliland was now quickly regained,” Churchill wrote with satisfaction. In two months, Italy’s Somaliland slice, Eritrea, and Ethiopia had also fallen to Commonwealth forces. in Washington, President Franklin D. Roosevelt could now proclaim the Red Sea as a non-belligerent area, so Lend-Lease aid could transit it to the Middle East.

The British later discovered that they would have to remarkably re-calculate their list of casualties during the fall of British Somaliland: Captain Eric Charles Twelves Wilson was discovered alive!

Somali survivors from Observation Hill, fleeing ahead of the oncoming Italians, had reported seeing Wilson dead at his machine-gun post after an explosion. He had only been knocked unconscious, however, later coming to and finding corpses all around. He stumbled down the hill the wrong way, straight into Italian hands, to be treated for his wounds and then consigned to a POW camp in Eritrea. Four months later a downed RAF pilot, arriving in the camp and surprised to find Wilson alive, informed the officer that he had been awarded the Victoria Cross. Wilson and other prisoners had been tunneling for weeks in preparation for a mass breakout when they awoke one morning to find the camp garrison had vanished except for the commandant, waiting to surrender to approaching British forces.

Charles Eric Twelves Wilson was the only “posthumous” Victoria Cross recipient ever to return alive. He went on to fight in Burma, serve in the Colonial Service in East Africa until 1961, and return to Somalia in 1975 to aid famine relief. Before he died at 96 in 2008, this “posthumous” Victoria Cross recipient was one of the last five living from World War II. He told the most recent Victoria Cross recipient, from Iraq, “It will not make a great difference in your life. You might get a few drinks, though.”

Captain Oscar Brooke reassembled his old Camel Corps company. All but two men, including one who had died, dutifully returned in a single day. Brooke’s devoted servant returned the next morning, having walked miles through the night to retrieve Brooke’s possessions, hidden from the Italians.

In 1960, having risen to brigadier and commander of the Somali Camel Corps, Brooke returned as an official representative when British Somaliland and the Italian portion (administered after the war by the United Nations) were to become jointly independent.

“While attending numerous functions and listening to a number of speeches by Somali politicians to Somali crowds,” Brooke recalled. “I was immensely struck by the fact that at no time was there a sour note, a snide remark, a cheap jibe or bitter comment—only a feeling of ‘good-bye to friends.’ And this despite the fact that the British record in Somaliland was nothing to boast about! On the final evening, as the Union flag came down for the last time, before the Somali flag was hoisted before the huge crowd a small group broke the silence by jeering and sneering. They were immediately and emphatically silenced, not by the police or soldiers, but by their own countrymen.

So, dignity was preserved to the last.”

Author John W. Osborn, Jr., is resident of Laguna Niguel, California. He has written for WWII History on a variety of topics.