By Zita Ballinger Fletcher

The famous retreat of the “Desert Fox” Erwin Rommel across North Africa following his defeat at the Second Battle of El Alamein in 1942 was less a retreat than a series of stubborn battles to hold ground. His opponent, British General Bernard Law Montgomery, was determined to expel the Germans from conquered territories in a momentous advance across the African continent.

Each commander lashed out at the other in a series of tense duels. Rommel, once renowned by British troops as a “magician” for his tactical skills, had not lost his legendary ability to opportunistically exploit the terrain and manipulate enemy weaknesses. Montgomery, a seasoned fighter with a passion for studying strategy, was eager to test his strength against a formidable opponent.

At the Battle of El Agheila, however, both generals were handicapped. Strapped with administrative weaknesses and political obligations, they faced each other across the battlefield with uncertainty. Both commanders urgently needed time to solve their armies’ troubles, but both were under pressure to act quickly. The battle would determine who held the gateway to Egypt.

The Build-Up: A Fighting Retreat

Rommel’s swift and seemingly unstoppable string of conquests across North Africa since 1941 was brought to a crashing end by Montgomery’s Eighth Army at El Alamein. The path straight to Cairo was now firmly closed to German troops, who had been plotting to seize control of the city for some time. Before his defeat at El Alamein, Rommel had already made a plan for seizing Cairo; his designs involved mobilizing Axis-friendly Egyptian “sleeper cells” within the city and detonating all Nile bridges to trap British troops inside the metropolis.

As Rommel’s war-weary troops en-camped 60 miles west of Alexandria, citizens began evacuating Cairo in anticipation of a German takeover. The unforeseen British victory at El Alamein had reversed the fate of Egypt and British troops in North Africa.

Even prior to El Alamein, Rommel’s personal morale had started to fray at the edges. His health was worn down by life on the grueling desert frontlines without reprieve. He had developed nasal diphtheria and low blood pressure, which forced him to receive frequent medical attention. Constant strategic arguments with German counterparts and squabbles with allied Italian commanders hampered his battlefield progress. His army’s supply line, stretched and targeted by British bombers, was failing—and, despite his constant demands for assistance, German and Italian bureaucrats were in no hurry to deliver aid. His writings during and after that time reflected disillusionment.

“It is sometimes a misfortune to enjoy a certain military reputation,” Rommel wrote. “One knows one’s own limits, but other people expect miracles.”

Despite all this, Rommel was confident enough to underestimate Montgomery before their first all-out battle at El Alamein. After all, he had played cat-and-mouse with the best of Britain’s commanders over the course of nearly two years, and he had won.

When Montgomery assumed command of the British Eighth Army in 1942, Rommel found himself faced with a shadowy opponent. Montgomery was a previously unknown entity in the British Army. Although respected by military peers for his prowess at tactics and physical training, Montgomery, dubbed “Monty” by comrades, was far from famous. He was a stranger to the desert war, and limited public information was available on him.

Rommel scrutinized his new opponent, tested him with a tank skirmish at Alam Halfa in summer 1942, and wrongly labeled him as overcautious. This misjudgment resulted in Rommel’s defeat at El Alamein and subsequent retreat to El Agheila.

While it was true that Montgomery was slow to react to Rommel’s maneuvers, this apparent inaction was not due to caution. In reality, Montgomery was an extremely meticulous and controlling personality. His writings reveal that maintaining complete control of situations was his ideal. He refused to smoke or drink alcohol because it represented a loss of mental and physical control.

Control was also one of his strongest battle principles; he refused to concede that any aspect of battle should be “dictated” to him by the enemy. After assuming command of the Eighth Army, Montgomery reorganized all forces under his authority until things suited him, ignoring Rommel until the right moment came to strike.

Montgomery also had the benefit of more experience. He was older than Rommel and had fought more battles than his German opponent. Rommel had previously won Germany’s highest decoration for valor as an infantryman during World War I. Montgomery had, in addition to fighting in World War I, served on the volatile frontier of present-day Afghanistan, fought in the Irish War of Independence, and seen action in a civil war in Palestine. Although new to the Eighth Army, he was battle-hardened and ready for action by the time of his first sparring match with Rommel in North Africa.

“It was true that I had never fought in the desert and I would have under me some very experienced generals who had been out there a long time. However, Rommel seemed to have defeated them all, and I would like to have a crack at him myself,” Montgomery recalled in his memoirs.

To complicate matters, Germany’s High Command had begun aggressively interfering in Rommel’s decisions. Third Reich propagandists had seized upon Rommel, spinning colorful fictions about him to suit their political agendas. Rommel’s human weaknesses and struggles were not acknowledged by German political leaders—his complaints and misfortunes no longer suited the Nazi narrative. As Nazi rulers worried about their world political image, they urged Rommel to behave according to their propaganda, however out of touch with reality it might be.

During Rommel’s crushing defeat at El Alamein, Hitler ordered him to “stand fast, yield not a yard of ground, and throw every gun and every man into the battle…. It would not be the first time in history that a strong will has triumphed over bigger battalions. As to your troops, you can show them no other road than that to victory or death.”

Rommel, plunged into confusion, realized later that Hitler’s order was only the first in a series of “propaganda commands” that would affect his decision-making authority for the duration of the war in North Africa. It shook him deeply.

“This order demanded the impossible. Even the most devoted soldier can be killed by a bomb…. We were completely stunned, and for the first time during the African campaign I did not know what to do,” he wrote. “This first instance of interference by higher authority in the tactical conduct of the African war came as a considerable shock.”

Rommel wrote that from then onward, he had to “continually circumvent orders from the Führer or the Duce to save the army from destruction.” Meanwhile, Rommel remained in control of vast territories across the North African continent he had captured in his previous conquests. He was reluctant to relinquish them.

Under Montgomery’s command, the Eighth Army had decisively defeated Germany’s most famous field marshal at El Alamein. However, Rommel’s defeat was not final. As the aggressive Afrika Korps desert troopers fled across the badlands in search of a new stronghold, they headed to a very familiar place—El Agheila, called Mersa el Brega by the Germans. This uncanny stretch of wasteland was known far and wide as the prime hunting ground of the Desert Fox.

The Phantom of the Wilderness

The ghost of Rommel’s past successes lingered at El Agheila, an eerie region of the Libyan wilderness filled with soft sand dunes and shimmering salt fields. Twice the British army had come to within an inch of victory at this spot, only to be forced to turn back by the Desert Fox.

The Agheila wasteland was like the threshold to a supernatural playing field where Rommel held dominion. He had made cunning use of natural elements, including sandstorms and the treachery of the open landscape, to wreak havoc on troops who pursued him here in the past.

“The Agheila position was naturally very strong. It covered the area of desert between the sea … which formed a difficult obstacle running east and west,” wrote Montgomery, who had been formulating plans to seize the region for a long time previously. “There were only a few tracks through this sand sea,” he wrote, “and so long as Rommel held the area, he could hold up our advance, or alternatively could debouch at will against us.”

Montgomery prepared an outflanking maneuver to encircle Rommel’s army. The left flank of the Afrika Korps was shielded by the Mediterranean coastline, while other areas of approach were hampered by natural obstacles. The Germans’ right flank, however, remained open across nearly 120 miles of desert. Montgomery planned to lead an assault on the front of Rommel’s army while also closing in to cut him off from behind.

It would be no easy task, Montgomery realized. “I did not think we would have any serious fighting till we reached Agheila,” he wrote. “Rommel would undoubtedly withdraw to that position and would endeavor to stop us there; his supply route would then be shortened while ours would be long, thus reversing the supply situation which had existed at Alamein.” He described Agheila as “a difficult position to attack.”

Despite his recent defeat, Rommel’s near-mythical reputation cast a growing shadow over the minds of his pursuers. Montgomery’s predecessor, British commander Claude Auchinleck, had written of Rommel in February 1942 that the German field marshal was “becoming a kind of magician or bogey-man to our troops … it would be highly undesirable that our men should credit him with supernatural powers.”

Although the command situation had changed, Rommel’s fearsome reputation persisted. The atmosphere around El Agheila was shrouded with gloom behind British lines. The men felt haunted and ill at ease.

The energetic Monty was unable to dispel his troops’ sense of foreboding regarding this area. “As we approached the Agheila position I sensed a feeling of anxiety in the ranks…. Many had been there twice already, and twice Rommel had … driven them back,” he wrote. Despite noticing “a feeling of depression” among his officers, Montgomery remained eager to fight. “I did not feel depressed at the prospect myself,” he noted dryly.

Yet this was a difficult situation for Montgomery to master. He liked to personally motivate and inspire his troops, delivering rousing speeches among the ranks to inflame their warrior spirit. “The troops must be brought to a state of wild enthusiasm before the operation begins…. They must enter the fight with the light of battle in their eyes and definitely wanting to kill the enemy,” he wrote of his approach.

Despite Montgomery’ efforts, the proud men of the Eighth Army grew more nervous with each step closer to the treacherous dune sea where their enemies lurked. The soldiers ironically made jokes about traveling to Libya for Christmas and returning to Egypt for New Year.

Montgomery realized the phantom presence of the Desert Fox was undermining his troops’ esprit de corps. “I therefore decided that I must get possession of the Agheila position quickly; morale might decline if we hung about looking at it too long,” he wrote.

Waiting long to start the attack was not an option in any case. Rommel was already moving—digging in defenses around El Agheila in what was known as the Agedabia region. The elusive wizard of the wilderness had reached his former stronghold and was mustering for battle. “The enemy was preparing to turn and face us,” wrote Montgomery.

The duel was soon to begin, but each general entered the battle suffering from strategic handicaps.

Off Balance

As Montgomery had predicted, Rommel’s supply difficulties were alleviated somewhat as he drew closer to Axis-held territories. However, the Afrika Korps’ need for materiel remained dire. During his retreat to El Agheila, Rommel’s Italian allies destroyed much-needed ammunition in a fit of sheer panic. “On top of all else, some overzealous people had blown up the ammunition dump at Barce along with the ammunition we were most short of,” Rommel wrote.

“The Italian Supply HQ had been overcome by a perfect frenzy of destruction. Ammunition dumps were blown up and water-points destroyed, all of which were urgently needed for the maintenance of the fighting troops. It was only at the last moment that we managed to stop them demolishing the water and electricity works in Benghazi.”

Additionally, the German High Command and their Italian counterpart, the Comando Supremo, were slow to respond to the reality that the impending battle at El Agheila would impact the fate of Axis control across the entirety of North Africa. While Rommel insisted that further damage to the Afrika Korps would result in the loss of Libya and tried to develop backup plans, higher authorities struggled to comprehend the situation and ordered him to hold his position indefinitely.

“We had still received no strategic decision from the supreme German and Italian authorities on the future of the African theatre of war,” wrote Rommel. “They did not look at things realistically—indeed they refused to do so.” Rommel was forced to wait for orders before making any major strategic decisions. The aggressive general hated being forced to hold back. “It was an ugly situation to have to stand immobilized for any length of time in the desert,” he wrote angrily.

Temporarily abandoned, Rommel had to devise his own plans for how to deal with the looming presence of Montgomery stalking him from a relatively short distance. Rommel brimmed with resentment at the British approach and ordered his men to sow a deadly trail of mines. These were no ordinary mines; many of the explosives were improvised “creations” devised by German sappers at the last minute. Some improvised mines known to have been created by the Afrika Korps included Luftwaffe bombs weighing more than 1,000 lbs., buried in shallow pits and rigged with tripwires. Rommel referred to the explosive devices as “neat little surprises” for the British.

Like Rommel, Montgomery’s own line of supply was stretched very thin, resulting in what he admitted was a perilous situation. “The pace of the pursuit was fast and the strain on administration became increasingly severe,” confessed Montgomery. “The advance was becoming sticky, and I was experiencing the first real anxiety I had suffered since assuming the command of the Eighth Army.”

He had chased Rommel relentlessly across vast distances of bleak wilderness. Now, not unlike his enemy, Montgomery was facing a supply crisis. Montgomery’s ability to properly replenish his troops and supply his army had become “a matter of urgent priority.”

“From Cairo to Tripoli is 1,600 miles by road…. It was as if GHQ were in London and the leading troops were in Moscow, with only one road joining them,” described Montgomery. Preceding the battle of El Agheila, a severe, unexpected rainstorm knocked advancing supply columns off balance, requiring supplies to be brought “a distance of 700 miles: equivalent to being disposed at Vienna and drawing stores in London with only one road available…. My whole force was stretched administratively, relying largely on Tobruk, some 450 miles by road in the rear.”

The situation was potentially disastrous for the British, and Rommel was a clever tactical opportunist. He preferred to exploit situations as they arose; most of his decisions on the frontlines relied on his opponent’s behavior. He was proactive in goading enemies to strike and constantly probed for weaknesses.

The aggressive Desert Fox eyed Monty’s position and zeroed in on its vulnerability. The British were isolated—the bulk of their fighting troops were concentrated forward, and a gap had formed between these troops and their lines of supply and reinforcement in the rear. This put Montgomery and his men in prime position for a stealthy, shark-like attack by Rommel’s panzers.

Rommel’s prior experience and killer instincts strongly inclined him to take the chance. “In January 1942, we had succeeded … in falling upon and smashing the British vanguard with locally superior forces before effective help could reach them,” wrote Rommel. He noted that the current scenario was “very similar” to past times when he had trapped his enemies.

Montgomery sensed his enemy’s intentions with some anxiety; he admitted that his position was “off balance.” Despite Rommel’s disadvantages, he did not doubt that the daring panzer general had the audacity to sneak around him and attempt to cut off his forces.

“My outflanking movement was necessarily weak owing to maintenance restrictions and it was launched into difficult country,” Montgomery noted, while Rommel’s position was “was immensely strong and very heavily mined.”

Rommel and fellow commanding officers discussed the idea of ambushing Montgomery. After a detailed discussion, Rommel—with uncharacteristic caution—ultimately decided the undertaking was too risky. “What made this so galling was that the British dispositions were excellently suited for such an operation,” he wrote, chagrined by his own decision.

As the pall of uncertainty thickened, political and strategic necessity demanded that both commanders take immediate action.

Rommel, pressuring Italian supervisors for crisis instructions and getting nowhere, flew to Germany for an emergency meeting with Hitler prior to the battle. He attempted to stress his dismal supply situation and suggest new approaches to strategy regarding Africa.

“Unfortunately, I then came too abruptly to the point and said that … the abandonment of the African theatre of war should now be accepted as a long-term policy,” he wrote. “If the army remained in North Africa, it would be destroyed. I had expected a rational discussion of my arguments,” he wrote, yet his remarks affected Hitler like a “spark in a powder barrel.”

Rommel, dumbfounded, witnessed Hitler’s temper explode for the first time. “The Führer flew into a fury and directed a stream of completely unfounded attacks upon us,” he wrote, unleashing “a violent outburst in which we were accused, among other things, of having thrown our arms away.” Although Rommel attempted to defend the Afrika Korps and urged measures to relieve them, Hitler refused to listen.

“There was no attempt at discussion. The Führer said that his decision to hold the eastern front in the winter of 1941-42 had saved Russia and that there, too, he had upheld his orders ruthlessly,” recalled Rommel. “I began to realize that Adolf Hitler simply did not want to see the situation as it was, and that he reacted emotionally to what his intelligence must have told him was right.”

The famed Desert Fox, once a beloved and respected hero of the German-Italian alliance, was now regarded with contempt by his superiors—a reverse in fortunes that filled him with cynicism as the hour for battle grew near. “Most of the Führer H.Q. staff officers present, the majority of whom never heard a shot fired in anger, appeared to agree with every word the Führer said,” Rommel recalled.

Describing higher staff at German and Italian headquarters, he wrote: “They believed the fault lay with us and thought they could improve our fighting spirit with bombastic and magniloquent phrases…. Me, they regarded as a pessimist of the first order, and they were probably the source of the legend which later went the rounds back in the rear—and was swallowed whole by certain office-chair soldiers only too anxious to delude themselves—that I was cocky in victory, but a prey to despair in defeat.”

Rommel was commanded not to yield his position. There would be no long-term withdrawal. Meanwhile, new interference in his authority came from the Luftwaffe. “Goering stated that I must at all costs hold on indefinitely … if possible, I should already begin attacking the enemy from Mersa el Brega [El Agheila],” he wrote. “Flying back to Africa I realized that we were now completely thrown back on our resources and that to keep the army from being destroyed as the result of some crazy order or other would need all our skill.”

Attacking with unfavorable odds was an equally high-stakes gamble for Montgomery. Failure to wrest the Agheila wilderness from the enemy’s grip meant the possibility of a lengthy and bloody siege for North Africa, and possibly a reversal in British fortunes.

“The problem,” he wrote, “was now to turn the enemy out of the El Agheila position as quickly as possible before he had time to perfect the organization of his defenses. I wanted to occupy the Agheila bottleneck myself … and thus ensure that the Axis forces would not hold the gateway to Cyrenaica a third time.”

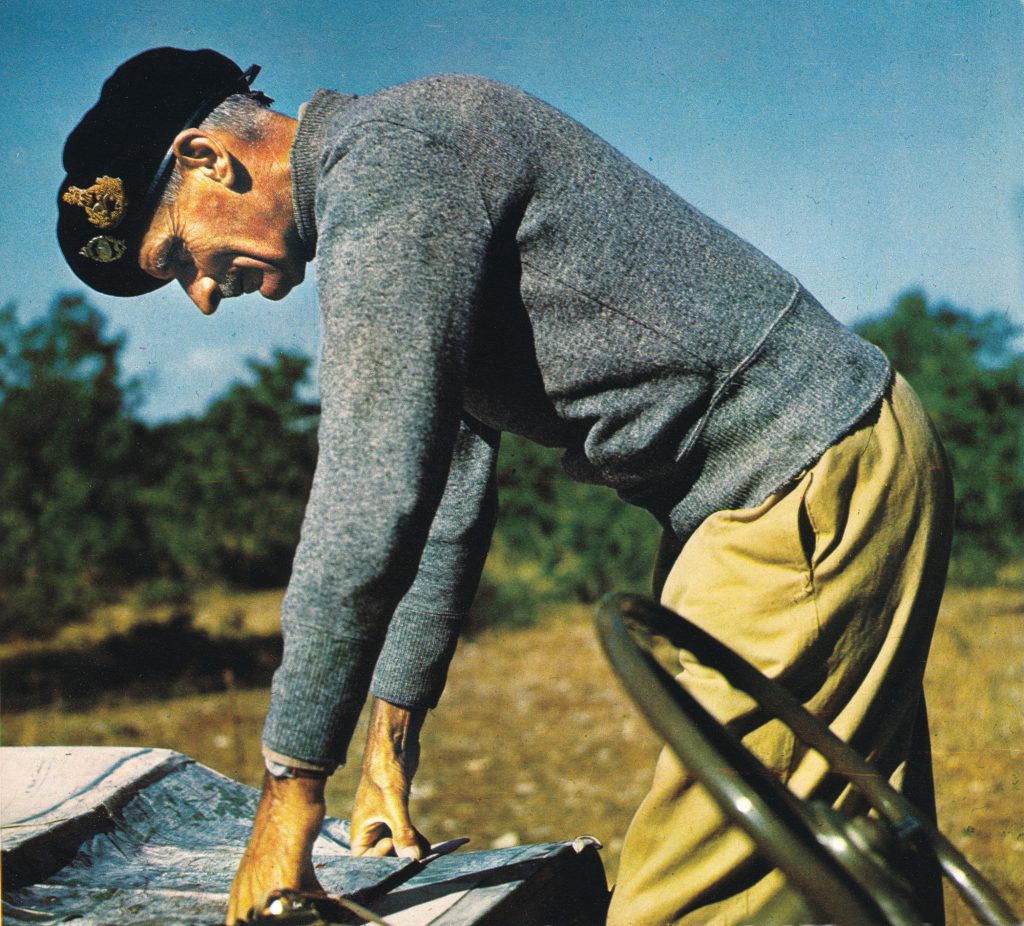

Montgomery realized he needed to carefully protect his front-line troops from severe damage, as it was impossible to bring any fresh forces forward quickly. “My next anxiety was the reinforcement situation. I could not at this stage risk a battle involving heavy casualties,” he recalled. Like Rommel, Montgomery used the lull as a chance for reprieve, flying back to Cairo for a weekend to discuss his plans at British army headquarters. “I also wanted to get some more clothes, and generally get cleaned up after nearly four months in the desert.”

After a comfortable stay in the British embassy, he returned refreshed for the fight. “When I got back to my headquarters just east of Benghazi … it seemed the enemy was becoming nervous about our preparations.”

As a cold winter night fell, scattered movements became apparent within the eerie sea of sand dunes. The Desert Fox was shifting his strength under cover of darkness. He started moving Italian infantry troops away from the forward area, withdrawing them to another defensible area called Buerat. Rommel hoped to keep his maneuvers secret. However, the element of surprise he needed was inadvertently foiled by his Italian allies.

“In spite of the need for secrecy … the Italians made an atrocious din and some of their vehicles even drove back through the moonlit night with blazing headlights,” Rommel wrote.

The movements caught Montgomery’s attention. Eager to thwart Rommel and bolster the fragile morale of British troops, he took action earlier than he had planned. He launched a full-scale attack.

The Roar of Battle

British troops commenced the attack with a barrage of heavy artillery fire on the night of December 11. The earth shook and white flashes pierced the black skies like lightning. Montgomery’s troops had already brought artillery forward, established supply dumps, and reconnoitered the battlefield. Raiding parties soon swept across the desert in vehicles and opened fire on German positions.

In keeping with his philosophy of total control, Montgomery refused to let Rommel dictate events on the battlefield. Rather than allow Rommel to retreat quietly, he decided to throw him off balance with what he described as “bluff and maneuver,” intended “to bustle Rommel to such an extent that he might think he would lose his whole force if he stood to fight.”

Rommel indeed believed that the British were attempting an all-out bid to overrun them. “The British made attack after attack against our strongpoints in the north and south, and soon there was no more doubt—the enemy offensive had opened,” wrote Rommel.

In fact, Montgomery’s forward assaults were a subterfuge. He hoped to herd Rommel’s panzers into an open area where they would be more prone to damage. “In view of the awkward country to the south and the difficulty of a frontal attack, it would obviously be preferable to maneuver Rommel out of the Agheila position and then attack him in the easier country to the west,” he wrote.

Meanwhile, British troops came unexpectedly face-to-face with old Afrika Korps enemies in the dusty wilderness—especially the formidable German 90th Light Division, which was nearly destroyed at El Alamein. The number of Rommel’s tanks had increased somewhat as supplies had been forced through to him from Europe, and British soldiers found it a somewhat spooky experience to witness the “resurrection” of the 90th Light Division—some elements of the Panzer Army seemed like ghost ships that would never die.

“We continued to meet old opponents right through to the bitter end of the campaign, and it used to be said that Eighth Army would be pursuing ’90 Light’ till the end of the time,” according to Montgomery, noting the uncanny scenario.

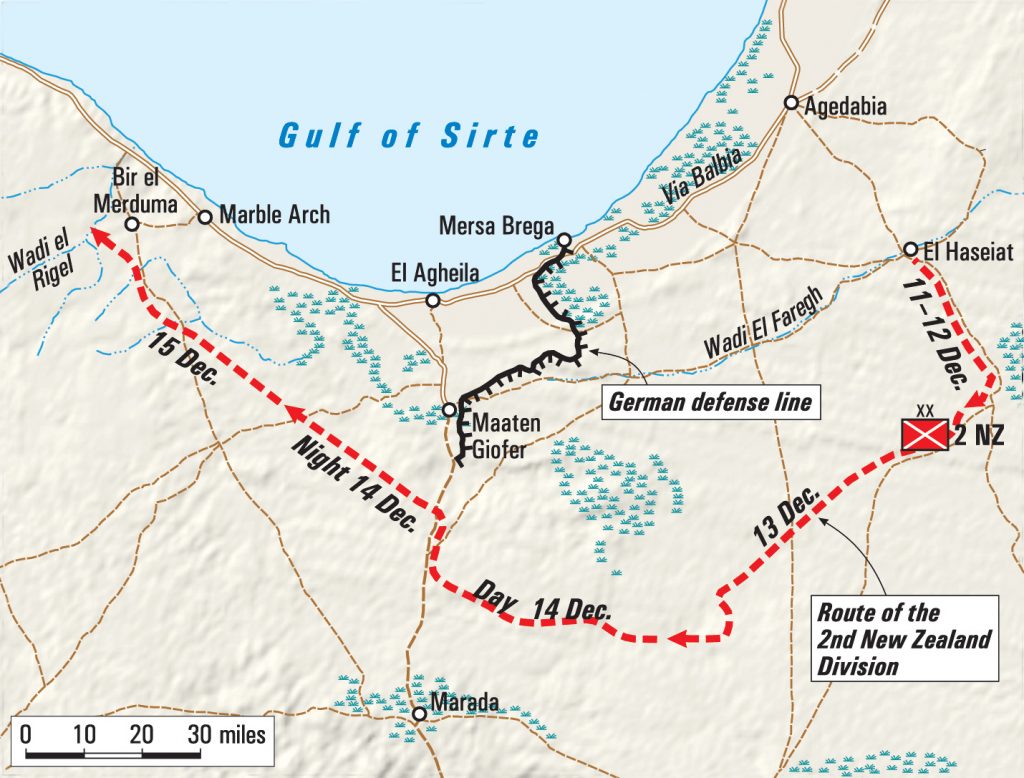

Rommel decided that to remain in the area would be “suicide.” He sounded the retreat as his staff sent incessant SOS messages to Europe. Even as Rommel pulled back, the New Zealand Division maneuvered behind the retreating Afrika Korps.

The Desert Fox was nearly encircled several times as the long arms of Montgomery’s army reached forward and choked his troops. At one point, the whole of Rommel’s Panzer Army was caught between the New Zealand Division and the rapidly advancing British 7th Armored Division. The British struggled to press onward across the rugged terrain of the dune sea.

“The Germans broke into small groups and burst their way through gaps in the strung-out New Zealand divisions,” according to Montgomery. He described fighting as “intense and confused,” and said the Afrika Korps was “severely mauled” during its escape. Over the course of the battle, Rommel’s forces sustained an estimated 20 percent casualties.

Rommel was livid with anger. He entertained thoughts of slicing advancing British tank columns to ribbons with guerilla-type assaults as he had done in the past. “It was infuriating for me to have to stand idly by and watch the wonderful opportunities which the enemy offered us for countermoves,” he wrote, adding he could have charged into the battlefield to cut off the enemy’s flank from its main force.

Montgomery had taken action knowing that Rommel had already committed his troops in a different direction. The British logistical weakness was exposed, but there was no longer any chance of Rommel being able to exploit it; things were moving too quickly.

The 90th Light Division and the Italian Combat Group Ariete fended off an assault from 80 British tanks that lasted nearly 10 hours. “The Italians put up a magnificent fight,” Rommel wrote. Eventually the British pulled back, leaving 22 tanks and two armored cars on the battlefield.

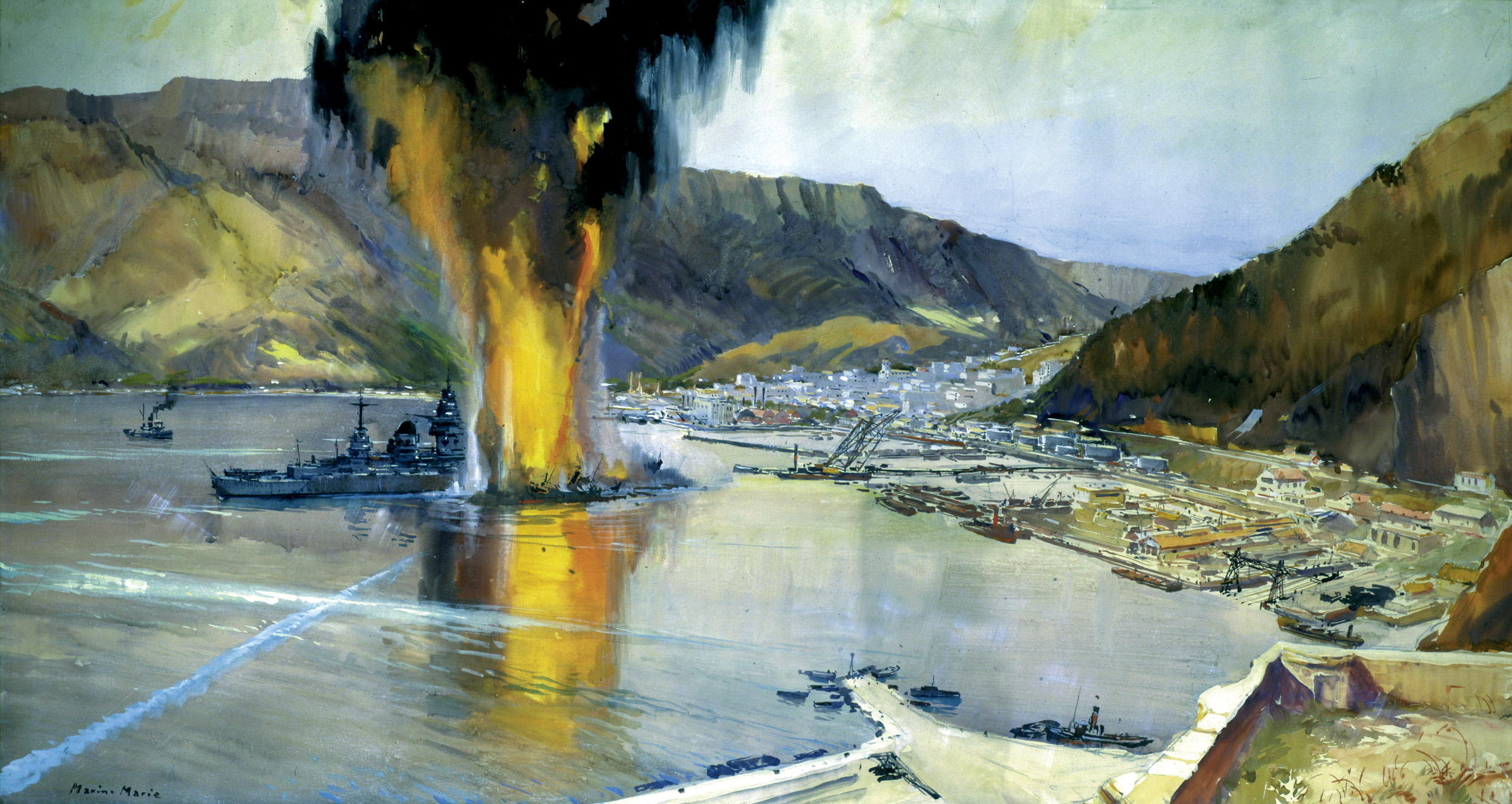

During the onslaught, the British also commenced a series of air strikes. Montgomery called the Royal Air Force his “long-range hitting weapon.” The bombardment was intended to unsettle the fleeing Germans during their withdrawal and protect British light infantry from Luftwaffe strafing. A bomber targeted Rommel’s forward headquarters, destroying the truck of his intelligence staff and other vehicles. The RAF also sank an Axis tanker and two fast ships laden with a total of 3,500 tons of petrol intended for Rommel’s troops.

Montgomery was adamant about keeping the attack constant and ferocious. “The enemy must be given no respite and no opportunity to organize defenses to delay us,” he wrote.

As fighting raged on December 16, the battlefield became confused as the British attempted repeatedly to surround the fleeing Afrika Korps. Prisoners on both sides were captured, freed, and recaptured again as sparring opponents tried to force their way back and forth through the difficult desert terrain.

On the morning of December 17, German tank crews faced a harrowing situation as they literally ran out of gasoline. They were immobilized as they fought swarming British tanks in what Rommel described as “a violent action.” The Germans were only able to launch a counterattack when some long-awaited fuel canisters arrived. Disabling 20 British tanks, they fled as quickly as possible.

The Desert Fox and his remaining troops escaped by a very narrow margin. “We had to use our last drop of petrol to get out of the sack,” he wrote, embittered. He promptly evacuated his troops to Buerat, located farther behind his frontline, where he had orders from superiors in Germany and Italy to make another desperate stand.

In doing so, Rommel effectively relinquished his stronghold of El Agheila, abandoning it completely for the first time since the early stages of the desert war. The “magician” of the dune sea had been expelled from his hideout.

“The Agheila bogey had been laid and we were leaguering as an Army beyond that once-dreaded position,” wrote Montgomery. “We had made the grade, and morale was high.”

The victory had a profoundly positive effect on the British troops in the Eighth Army. Private Geoffrey Glaister wrote to Montgomery on December 23, 1942: “For the first time in my Army life I felt I belonged to something…. For myself, thank you, Sir, for this new feeling. You have made us proud to belong to the 8th Army … I again on behalf of thousands of us here in Libya—on behalf of this great brotherhood, thank you sincerely.”

Montgomery ordered the New Zealand Division to halt and reorganize, and followed up Rommel’s army with light forces, renewing contact with them in the Buerat position. More battles lay ahead—Montgomery was already hell-bent on hacking a path forward to Tripoli, Libya’s wild and luxurious capital city on the Mediterranean coast. “The enemy will try to stop us,” he vaunted to his troops. “Nothing has stopped us since the Battle of Alamein began on 23rd October 1942. Nothing will stop us now…. On to Tripoli!”

Monty moved his tactical HQ to a locale known as Marble Arch—a site where Mussolini’s fascist artisans had erected a triumphant white arch in the middle of nowhere. Called the Arco de Fileni by Italians, the portal was crowned with a pair of gruesome bronze statues showing the legendary Philaeni brothers of ancient Carthage being buried alive for the glory of empire. (The arch was destroyed by Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in 1973.)

Montgomery situated himself near airfields in an ideal position to direct the reconnaissance of enemy troops lurking in Buerat and plot his steamrolling advance. “We were now well into Tripolitania, and over 1,200 miles from Alamein where we had started,” he noted. “Rommel and his Axis forces had been decisively defeated. Egypt was safe for the duration of the war.”

Aftermath: A Desert Christmas

As Christmas approached the dusty troops in the cold barrenness of the desert, Monty opted to give his men a break. “I decided that the Eighth Army needed a halt … officers and men deserved a rest and I was determined they should have it,” he wrote.

Montgomery was touched by a feisty Christmas greeting he received from an anonymous “Yorkshire lass.” “Keep ‘em on the run, Monty,” she wrote. He shared the letter with his men and recalled the occasion later with fondness. “It was very cold. Turkeys, plum puddings, beer, were all ordered up from Egypt.”

Cracking open a bottle of port, Monty and a large group of his administrative officers gathered together for a very lively evening. Despite his self-styled health regime forbidding alcohol or tobacco, Monty had a boisterous personality and encouraged camaraderie among his staff.

Partaking in the gathering were two of Monty’s best friends: Charles Sweeny, a sarcastic Irish orphan who viewed Monty as a father figure, and John Poston, a rakish young cavalry officer known for his love of smoke, drink, and ribald humor.

With his sober self-discipline and Spartan obsession with warfare, the much-older Monty had little in common with these young rascals, yet he became close to them. Isolated and burdened by high-command responsibilities, Monty found relief from his stressful job duties in witnessing the clowning of the rowdy young men.

Both Poston and Sweeny were killed in the last days of the war after having loyally served Monty for years on the front lines. Yet they and other faces from the Eighth Army would forever live on in Montgomery’s memory, celebrating that Christmas Eve party with him amid much toasting, drinking, joking, and singing.

“I enjoyed that Christmas in the desert. I think we all did,” Montgomery wrote later. “We had a feeling that we had achieved something.”

The atmosphere at Rommel’s headquarters was less festive. Nevertheless, the Germans, for all their difficulties, were also eager to celebrate Christmas. Rommel wrote to his wife that his men were “in top spirits, thank God, and it takes great strength not to let them see how heavily the situation is pressing on us.”

His thoughts turned towards home; it was his son Manfred’s 15th birthday. He penned a greeting to his family and went for a drive across flowery green meadows—a vastly different environment from the wastes of El Agheila. A herd of gazelles trotted towards the vehicles. Rommel recognized “Christmas dinner” and promptly went on a hunting spree; he was accustomed to shooting North African game from command vehicles using a pistol. “Armbruster (an interpreter) and I each succeeded in bringing down one of these speedy animals from the moving cars,” Rommel wrote.

Attending his headquarters Christmas party later in the day, the Desert Fox received a cynical gift from his men. “I received a present of a miniature petrol drum containing, instead of petrol, a pound or two of captured coffee,” he noted, not missing the irony. “Thus, proper homage was paid to our most serious problem even on that day…. At 2000 hours I invited several people from my immediate staff to share a meal off the gazelles we had brought in that morning.”

Despite the brief respite of Christmas, the war in North Africa was far from over. The two opposing generals were destined to grapple again in a further sequence of brutal clashes. One thing was certain: Rommel’s loss of the El Agheila position effectively closed the Third Reich’s access to Egypt forever.

Reflections on the Battle

Describing his North African endeavors in his memoirs, Montgomery later reflected: “In battle, the art of command lies in understanding that no two situations are ever the same; each must be tackled as a wholly new problem to which there will be a wholly new answer.”

The situation at El Agheila was certainly very different from any that either side previously experienced. As both commanders struggled to guard their weaknesses, they were forced to come to blows for the first time since their hard clash at El Alamein. Neither of them had any idea what to expect.

Even with his limited fuel supply, Rommel could have held El Agheila, exploiting natural defenses and the overextended British supply line to wear down his enemy. Yet the Desert Fox chose to withdraw from the area before the battle had been decided. Was this bitterness or pragmatism?

“I was angry and resentful at the lack of understanding displayed by our highest command and their readiness to blame the troops at the front for their own mistakes,” wrote Rommel, preoccupied with increasing feelings of disillusionment towards his country’s leadership. Furious that Hitler and army chiefs had ignored his requests for supplies, he expressed little hope for success before the battle began. “We were up to our necks in the mud and no longer had the strength to pull ourselves out,” he wrote grimly.

The point of view was very different on the other side of the battlefield. To win against Rommel at Agheila “might have been very difficult for me,” according to Montgomery. “It was the first defensive position at which he had the opportunity to face our advance with any chance of success, yet we turned him out of it with comparative ease.”

For his part, Monty continued to wonder afterwards why Rommel had chosen to withdraw from El Agheila without attempting to make a tougher stand. “I can think of no sound military reason for Rommel’s decision to stop at Buerat,” he wrote, citing Rommel’s hasty removal to a more distant location in the wake of action at El Agheila. “I believe that Mussolini ordered it and that Rommel could not disobey until our advance gave him the excuse. By then it was too late.”

Although it was true that Axis commanders had ordered Rommel’s relocation to Buerat, they did not order him to make a hasty withdrawal—German and Italian commanders had clearly urged Rommel to stay at El Agheila and fight. Why Rommel, despite natural advantages in the terrain and an obvious weakness in Montgomery’s army formations, ultimately declined to put up a more determined struggle for the territory remains a mystery.

The Battle’s Effect on Rommel & Monty

The war in North Africa has been largely viewed as a “gentlemen’s war”—both British and German opponents engaged in combat in what is seen as a chivalrous manner, humanely and without atrocities. In the postwar era, many men from the British Eighth Army befriended former enemies from the Afrika Korps. Their shared experience of desert warfare created a strange bond between them. The outcome of battles such as El Agheila left many of these men without feelings of hatred for one another. However, the North African struggles seem to have had a different effect on Rommel and Montgomery.

Judging from his writings, Rommel appears to have developed some resentment against Montgomery. While he enjoyed analyzing enemy generals, including former British opponents Auchinleck, Wavell, and Ritchie, Rommel gave no such literary treatment to Montgomery—in fact, he rarely mentioned Montgomery’s name in writing. In many instances, he dubbed him only “the British commander.”

Few appraisals of Montgomery’s ability exist in Rommel’s written work, aside from a few acrimonious criticisms—instances where Rommel claimed “the British commander” should have known better, or could have done better. The closest Rommel ever came to complimenting Monty was a brief sentence stating that Montgomery “never made a serious strategic mistake.” This seems to evidence feelings of bitterness or antagonism. If true, it would be hardly surprising; Montgomery was, after all, the architect of Rommel’s military downfall—the first enemy who had ever soundly beaten him in combat, and more than once.

Rommel mentioned once cynically listening to a Cairo radio broadcast that vaunted Montgomery’s success. Monty’s star rose as Rommel’s fell; he skyrocketed to fame while Rommel was disgraced and stripped of military powers. This seems to have had a chilling effect on the German commander.

A similarly unusual silence occurred on Montgomery’s part. He rarely mentioned Rommel after the war except to explain how he defeated him. Montgomery later said to his family that he wished he could have met Rommel in person. Monty appears, though, to have made no statements of soldierly admiration for Rommel either during or after the war—either in public or in published writings. Former opponents of the Desert Fox praised him as a “good man”; even Winston Churchill referred to Rommel in a speech as “a great general.”

Montgomery was a very deliberate man; it is unknown whether his silence about Rommel was due to some unspoken principle or lingering wartime antagonism. Interestingly, unlike many Eighth Army veterans, Montgomery also gave no praise to the German troops he’d fought against. Perhaps his battles against Rommel had left Monty with experiences that he found difficult to express or forgive.

In contrast to the troops who fought under their command, it would seem the two generals became personal enemies during the war. El Agheila marked only the beginning of what would become a long series of hostile engagements between the two men, who were destined to constantly face off against each other in North Africa before their ultimate showdown on D-Day in 1944.