By John Wukovits

In mid-December 1941, during the thick of the Battle of Wake Island, the 400 U.S. Marines who called the island outpost home stood a lonely sentinel in the watery Central Pacific wilderness, like a cavalry fort in an oceanic version of the Western frontier.

As the Japanese juggernaut spread the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere to the farthest reaches of the Pacific Ocean, most of America’s Pacific battle fleet, the backbone of the nation’s power in the hemisphere, rested on Pearl Harbor’s muddy bottom along with almost 2,000 young American sailors. Marines on Guam and British infantry in Malaya were fighting futile holding actions against swarms of enemy troops. In the Philippines, Japanese bombers demolished General Douglas MacArthur’s air force before it lifted from the ground, and Japanese infantry forced his troops into a disastrous retreat toward the Bataan Peninsula.

Next on Japan’s Timetable of Conquest

Hong Kong and Singapore were poised to fall, and the crowning blow—the destruction of the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser HMS Repulse at the hands of Japanese planes off Malaya—caused British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to lament, “Over all the vast expanse of waters Japan was supreme, and we everywhere were weak and naked.”

Barely 600 miles—less than two days’ steaming time or four hours’ flying time—from the closest Japanese base, Wake was next on Japan’s timetable of conquest. Wake, a coral atoll comprising three islands, whose highest point was barely 20 feet above sea level and whose vegetation consisted of scrubby trees and brush, covered four square miles of total land area. Yet, even this tiny real estate, with 10 miles of beach, offered too much territory for the tiny garrison to cover. Should the Japanese crash ashore in one of the numerous gaps between gun emplacements, the Americans would be swiftly overrun. A desperately needed radar system had not yet arrived.

Fearing that he could not withstand even the feeblest of assaults, Major James Devereux, the Marine commander, asked his superiors what he should do if Wake were actually attacked. He received the disconcerting response, “Do the best you can.”

Why would one of the war’s most noble actions occur at a minuscule Pacific wasteland more suitable for rodents than humans? It boiled down to the airstrip, which dominated the V-shaped group of three small islands. Control of that airstrip loomed more crucial with the deteriorating Japanese-American relations before Pearl Harbor. In U.S. hands, Wake posed a threat to the Japanese wall of defenses, which stretched across the Central Pacific. In Japanese hands, it offered a convenient home base for aerial reconnaissance of Hawaii, Midway, and other U.S. possessions.

Before the war, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, the Pacific Fleet commander, sensed a chance to engage Japan’s fleet in the waters off Wake if an invasion force attempted to overrun the island’s defenders. To hold the enemy in the area, though, Wake’s feeble defenses had to be strengthened. Kimmel ordered in a Marine defense battalion under Devereux, and more than a thousand civilian construction workers converged on the desolate outpost to erect barracks, level roads, and fortify the island.

On October 12, 1941, when Major Devereux stepped onto Wake Island, he brought additional reinforcements to join the original group of five officers and 173 enlisted men who had arrived August 19. A larger Marine force meant increased contact and inevitable friction with the construction workers.

Not that fighting erupted or jealousies lingered. The two groups blended together relatively well, for, after all, as Marine Corporal Franklin D. Gross said, “We were Marines and we were disciplined and knew what we were supposed to do and what not to do.” But each day the Marines emerged from their Spartan tents to gaze across the lagoon at the more luxurious civilian quarters. While Marines supped on potatoes, civilians feasted. Marines chafed at the obvious differences.

Devereux turned to his task with a fury, intending to transform this first line of defense in the Pacific into a bastion that could punish any approaching force. “When Devereux came out there, all hell broke loose!” declared Gross. “He evidently had orders to get those guns in, so we worked seven days a week. Before that, I’m not sure we even worked on Saturday.”

The wiry major, who so meticulously planned details that a fellow officer said, “He’s the kind of guy who would put all the mechanized aircraft detectors into operation and then station a man with a spyglass in a tall tree,” quickly had his men laboring 12-hour days, seven days a week.

Intentions are noble, but they must be backed with men, weapons, and supplies, and here Devereux suffered. The U.S. Congress had allocated money to improve Wake, but the work did not begin until early 1941. Shelters to protect aircraft from bombs lay incomplete. Devereux’s 3- and 5-inch guns equaled the impact of a destroyer, but he commanded enough Marines to man only half the 24 machine guns situated about Wake. Instead of radar to give advance warning of attack, a man with a pair of binoculars on an observation post atop a water tower served as the island’s early-warning system.

Communications wire connected different outposts, but since much of it was old and frayed, no one knew how it would stand up to a heavy bombardment. In the most extreme situations, when soldiers and Marines had little else with which to fight, they could always count on using their rifles. Not at Wake Island. At least 75 men lacked weapons because the military had failed to ship enough to the outpost.

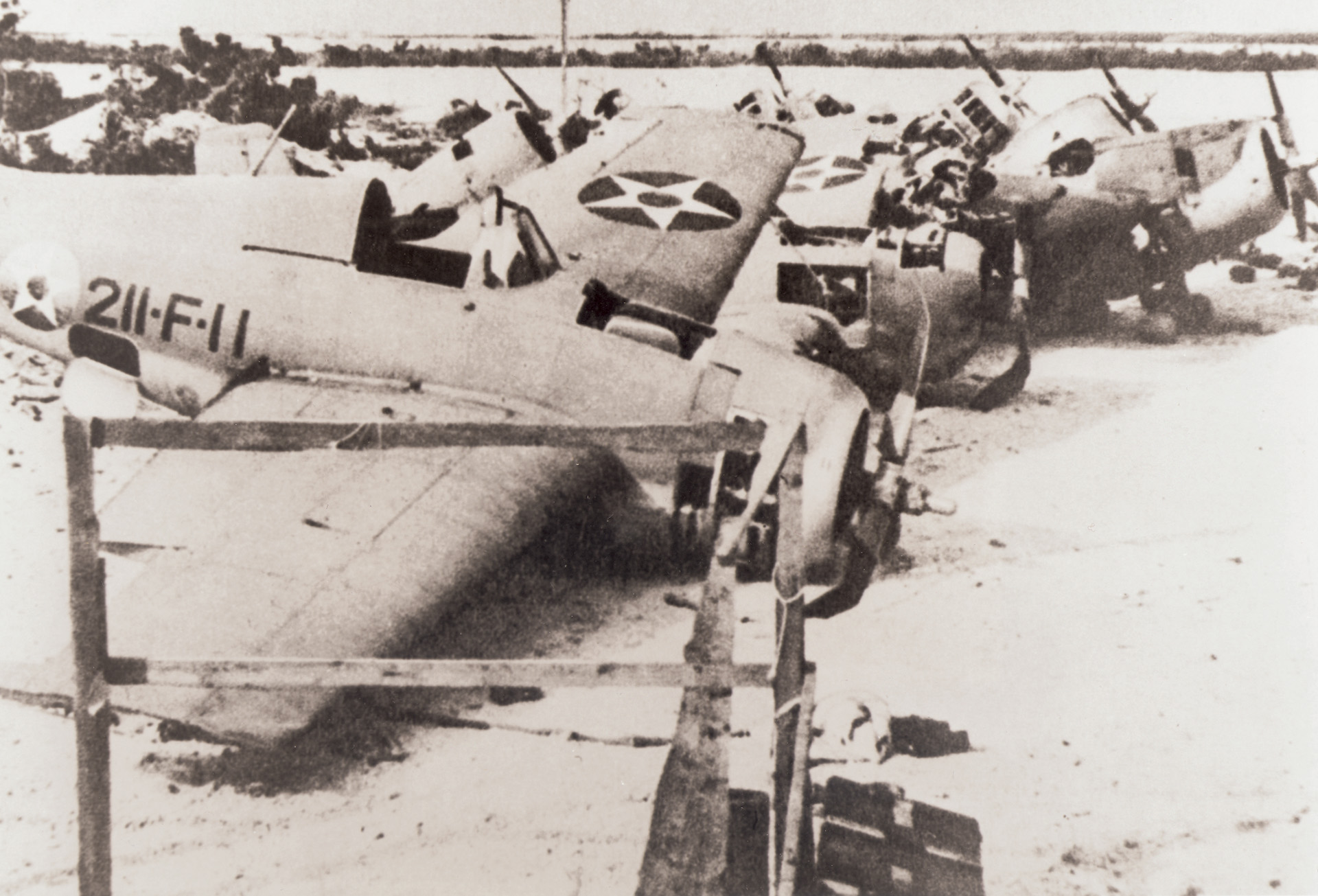

Devereux’s air arm offered minimal help. The 12 Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters failed to arrive until four days before the war started. Since the ground crews and aviators had been working with biplanes instead of the fighters, they were unfamiliar with the capabilities of the aircraft. Mechanics rummaged through the crates of supplies that accompanied the planes for instruction manuals, but could find none. Someone at Pearl Harbor had forgotten to pack them. Spare parts for the aircraft were practically nonexistent, which meant that even minor damage could knock them out of the fighting. In the frontier wilderness of the Pacific, a damaged aircraft was as good as a destroyed aircraft.

By late November 1941, although still far from complete, Wake had been bolstered sufficiently to earn the designation of naval air station. Commander Winfield Scott Cunningham arrived to assume overall command, with Devereux in charge of the Marines.

Most Marines and civilians on Wake believed that war, if it occurred, would start elsewhere in the Pacific, probably closer to the Philippines or East Asia. When they learned on December 7 that Pearl Harbor, far to Wake’s rear, had been bombed, they reacted in disbelief.

Devereux, expecting to be attacked at any moment, ordered each man to his post. Even with the precautions, war’s arrival on Wake shortly before noon on December 8 (December 7 in Pearl Harbor) came swiftly and suddenly. Construction worker Hans Whitney looked skyward to see a group of aircraft heading toward Wake. He mistakenly assumed they were American planes and said to a companion, “Look! Let the Japs come! We even have bombers, now!”

15 Seconds’ Notice: The Battle of Wake Island Begins

Without radar to give early warning, the tiny Marine garrison had barely 15 seconds’ notice, hardly enough time to ready their antiaircraft guns and jump into aircraft. Still, they replied. Gross’s position at the eastern end of Wake, called Peacock Point, sported four machine guns. “I was standing on top of my dugout talking to Colonel Hanna when 18 to 19 planes dropped out of a hole in the clouds. I said, ‘What’s this coming in?’ We thought they were B-17s, because they had been coming in for the last few months and we’d gas them. Suddenly these bombs fall out, and a runner near me started shooting, but we only got off 18 rounds. Then the planes were gone.”

In that brief span the Japanese inflicted heavy damage and shock to Wake Island’s Marines. Four Marine aviators rushed toward their aircraft intent on offering resistance to the 36 Japanese twin-engine bombers that riddled Wake, but not one reached his plane. Bomb fragments fatally tore into Lieutenant Frank Holden as he sprinted onto the runway, while Lieutenant Henry G. Webb fell with lethal wounds to the stomach and feet. Lieutenant George Graves had climbed into his aircraft and prepared for takeoff when a direct hit engulfed him in flames. Lieutenant Robert Conderman evaded the bullets that spit into the coral airstrip until he reached his aircraft, then bomb fragments tore into his body. Fellow Marines rushed to his aid, but the dying Conderman pointed to other wounded Marines lying about the area and said, “Let me go. Take care of them.”

Benjamin F. Comstock, Sr. and his son, Benjamin, Jr., were working on a two-story, steel framework building when the Japanese aircraft suddenly appeared. In an action symbolic of the sacrifices to be made by millions of sons around the nation to protect their families, the son quickly tackled his father, shoved him behind a stairway in the unfinished building, then covered him with his body. “The planes were so close you could see the gunners’ teeth,” recalled Comstock, Jr.

Bomb craters 50 feet apart spotted the ground with surgical precision, except for the airstrip. It remained untouched so the Japanese could use it after their conquest. Seven precious Wildcat fighters lay in smoldering ruins amid the lifeless bodies of 23 Marine aviation personnel. The Japanese blasted gasoline storage tanks, strafed the island’s Pan American Airways hotel, and peppered Pan Am’s huge flying passenger boat Philippine Clipper with 23 bullet holes.

As if to add insult to injury, as the enemy aircraft completed their runs, “The pilots in every one of the planes was grinning wildly. Every one wiggled his wings to signify Banzai,” mentioned a defender.

A Citizen Soldier Army Assembles

Marines and civilians emerged from foxholes and half-completed construction projects and quickly tended to the wounded and dying. Billowing smoke blotted out the sun and burning wreckage littered the landscape, but the men put aside their thoughts and focused on the job at hand, which was preparing for the inevitable invasion. They repaired severed communications lines, camouflaged and sandbagged gun positions, cleared the runway, and dug revetments to protect the few remaining aircraft.

Civilians parked heavy construction equipment on the airstrip to prevent Japanese landings, while a Navy lighter was filled with concrete blocks, dynamited, and anchored in the center of Wilkes Channel to prevent small boats from entering the lagoon. Since they had little time to spare for burials, Marines stored the dead civilians and Marines in a large freezer room in one of the civilian buildings.

The citizen soldier army, so heralded in contributing to victory in Europe and the Pacific, made its first appearance at Wake as 200 volunteers dropped their shovels or stepped down from bulldozers to stand side by side with the 400 Marines. They had traveled to Wake for monetary reasons, not to fire weapons, but when the chips were down they answered the call of duty like their Marine compatriots. Most were sent to undermanned batteries and given speedy instructions on how to fire the weapons. Hans Whitney was stationed at an antiaircraft gun, where he filled sandbags and waited for a renewed attack.

Apprehension frayed nerves and exhausted even the sturdiest of men, who never knew when the main Japanese assault would come. Some believed the U.S. Navy would charge out of Pearl Harbor to their rescue, but others wondered if it even could. How severely had it been wounded on the war’s first day? Was Wake to be sacrificed by an impotent Navy, or would a rescue force save them?

In those perilous days immediately after December 8, Marine Pfc. Verne L. Wallace remembered a letter from his girlfriend back home that he had stuffed unread into his pocket. In a few quiet moments, he sat down and looked at the letter. The girl had sent it before December 7, and thinking that Hitler posed the real threat to American servicemen, she wrote, “As long as you have to be away, darling, I’m so very, very happy you are in the Pacific, where you won’t be in danger if war comes.”

Drawing in the Japanese

The irony of the situation did not escape Wallace, sitting in the middle of a Japanese-controlled ocean, for danger crept closer as he read the note. In the predawn moments of December 11, the Japanese, invigorated by the list of triumphs already under their belts, commenced their first attempt to overrun Wake. Confident of victory over what they assumed was a ragtag group of civilians and a few Marines, the Japanese stepped into a trap cunningly devised by Major Devereux. Devereux outfoxed the enemy commander, Admiral Sadamichi Kajioka, into thinking he had surprised Wake. Since the Japanese force sported much larger guns than those on Wake, Devereux’s only hope was to hold his own fire and lure the enemy ships within range of his smaller 5-inch guns.

Admiral Kajioka, in the flagship Yubari, cautiously led three light cruisers, six destroyers, and 450 soldiers in transports and old destroyers toward Wake. Optimistic reports from the returning bomber pilots and a lack of activity on Wake as his ships neared the island bolstered Kajioka’s confidence that taking Wake should be a breeze.

Lookouts on Wake first spotted the Japanese at 3 am. Kajioka swung west when his ships drew within 7,000 yards, opened fire at 5:30, and systematically raked the island as the flotilla boldly steamed along its coastline. When the Japanese ships reached Wake’s westernmost point, Kajioka reversed course, closed the distance, and again steamed offshore with guns booming. The lack of American return fire convinced Kajioka that he had caught the enemy by surprise.

Marines at two gun batteries impatiently awaited Devereux’s order to fire as they watched the enemy shells inch alarmingly close and felt the vibrations from nearby explosions. A corporal manning Devereux’s phone spurned pleas to open fire by shouting, “Hold your fire till the major gives his word.” One Marine, dodging mounds of earth shaken loose from bombs, griped, “What does that dumb little bastard want us to do? Let ’em run over us without spitting back?”

Devereux coolly waited for another 30 minutes. When the unsuspecting Kajioka drew into point-blank range, he ordered all batteries to commence firing. Like Wild West gunslingers glaring at their foes, his gunners on batteries A, B, and L poured accurate salvos into the Japanese ships barely 4,000 yards away. Shells smashed Japanese hulls, and shrapnel felled Japanese sailors. The enemy attempted to fire back, but the Marines continued to pummel the attacking ships.

The only thing more stunning than the cascading Marine fire that broke the darkness was the look of dismay on Kajioka’s face as he realized he had been lured into the Marine guns. An initial salvo screamed over the Yubari, and as destroyers hurriedly spread covering smoke to shield the flagship, a second salvo straddled the ship. Marine gunners pumped four successive shells into the hapless cruiser, enveloping one side in fire and smoke.

Three shells from a second battery sent the destroyer Hayate and its crew of 168 to the bottom. Marines lustily cheered as the ship disappeared beneath the waves until veteran Platoon Sgt. Henry Bedell turned their minds back to business by yelling, “Knock it off, you bastards, and get back on the guns! What d’ya think this is, a ball game?”

A Humiliating Defeat for Admiral Kajioka

When the Marines landed hits on three more destroyers and on a transport, Kajioka ordered his force to retire. Major Paul A. Putnam, commander of Wake’s air squadron, now jumped into the fray. Putnam’s Wildcats pounced on the retreating Japanese ships in a series of attacks. Captain Henry Freuler damaged a transport, while Captain Henry Elrod and Captain Frank Tharin scored hits on the cruisers Tenryu and Tatsuta. Another aircraft machine-gunned the Yubari, barely missing Admiral Kajioka.

The destroyer Kisaragi, which lagged behind the rest of Kajioka’s force, paid the highest price. Her tardiness in leaving proved to be her undoing when a bomb, attributed to Elrod, hit the destroyer’s quarterdeck and ignited the ship’s depth charges. Explosions ripped apart the destroyer, which sank within minutes.

Admiral Kajioka absorbed a humiliating defeat at the hands of a vastly outnumbered foe. He lost two ships and at least 340 killed and 65 wounded against one Marine death. The Japanese limped away from the gunfight, while the United States celebrated its first victory of the war.

Marines registered three “firsts” on Wake that day. For the first and only time in the war, an invasion had been repulsed by shore batteries. The first Japanese surface warship had been sunk. Most important, for the first time since the war started, the Japanese had been stopped in their desire to gain an objective.

The defenders on Wake erupted in joy, dumping water on each other and behaving like schoolboys. Cunningham later compared the celebration to a “fraternity picnic. War whoops of joy split the air. Warm beer was sprayed on late arrivals without regard to rank.” At the end of the day Devereux’s radio operator remarked, “It’s been quite a day, Major, hasn’t it?”

But their reaction was nothing compared to the reaction back home, where victory-starved civilians, still in shock over Pearl Harbor, received the news with elation. People had already begun wondering where the U.S. Navy was, since it had not made an appearance since the December 7 debacle, but they at least knew where the U.S. Marines stood—on a tiny Pacific speck where American military forces repelled the seemingly invincible Japanese. Headlines proudly proclaimed, “MARINES KEEP WAKE,” and compared its gallant defense during the Battle of Wake Island to the valiant stand at the Alamo.

They took heart in the news of Wake’s heroic stand, for if such a small garrison on a barren isle could perform that well, what might the Japanese expect once the United States sent its vast, well-supplied armies into conflict? Americans finally had something to cheer about, and while they hated to think of loved ones being killed or wounded, they knew that once their sons were organized and marched to war, momentum would swerve to the United States.

Immediately after the battle a Japanese Naval officer assessed Kajioka’s performance against the garrison at Wake. He concluded that Wake proved to be “one of the most humiliating defeats our navy ever suffered.”

Wake’s defenders had taken Round 1. Round 2 was about to begin.

Every Marine on Wake knew that the Japanese would return for a second assault, this time with enough men and ships to avoid another setback. The only question was when the attack would occur. The Pacific was fast turning into a Japanese ocean, with Japan’s only challenges coming from a weakened U.S. Navy and from Wake. With each passing day, the garrison became more isolated from the rest of the world.

“The Foggy Blur of Days and Nights When Time Stood Still”

Over the next 12 days the men, already weary from the strain of war, turned spectral from the constant state of vigilance and from daily Japanese air raids. Not knowing when an invasion force might suddenly loom offshore, Marines and a handful of civilians had to remain around the clock at their gun positions, where hot food and a chance to relax were luxuries from a past that had disappeared. No man could catch more than a few moments’ rest, since daily waves of fighters and bombers gave them little respite from combat conditions. Like automatons, exhausted men emerged after each raid, hastily repaired what they could, removed the wounded and dead, and prepared for the next wave of bombing. Diarrhea afflicted many. The island’s huge native rats—bothered by the bombings—swarmed into shelters and foxholes, while innumerable dead birds had to be buried for sanitation purposes. Supplies dwindled with each raid.

Devereux called this period the “foggy blur of days and nights when time stood still,” when men ached for laughter and one decent night’s sleep. “The days blurred together in a dreary sameness of bombing and endless work and always that aching need for sleep. I have seen men standing with their eyes open, staring at nothing, and they did not hear me when I spoke to them.” The only thing that counted was survival.

Marines and civilians rose from their shelters after each bombing, looked around at the new devastation, then permitted a small smile to briefly appear. “It was like a great weight lifting from your chest,” wrote Devereux. “You wouldn’t die today.”

Civilians Continue to Chip In

Through these weary days of mind-numbing bombing, the men on Wake displayed a remarkable resilience and self-sufficiency. They bided by the old Marine saying, which warned, “Maybe you oughta get more, maybe you will get more, but all you can depend on getting is what you already got.” Devereux again outwitted his opponents by moving the antiaircraft guns almost every night. He correctly assumed the Japanese bombers would mark the gun emplacements for subsequent attacks, so following each raid he ordered his tired Marines to shift the guns. When the next attack occurred, bombs usually fell on the abandoned positions.

Marine mechanics worked marvels to keep the four remaining fighters aloft, trading engines from one plane to another, stripping crashed aircraft for parts to build a hybrid version, and once even pulling a precious engine from a still-burning aircraft.

Some civilians added their own contributions. Dan Teters, a World War I veteran, organized a delivery system that shuttled food to the men at their posts. Appreciative Marines fondly labeled it “Dan Teters’ Catering Service.” In the absence of a military chaplain, a Mormon lay preacher named John O’Neal visited foxholes or comforted the wounded. Others carried ammunition to gun positions. Earl Row took his turn at the nightly beach patrols, a duty he called “the most hair-raising thing I have ever done in my life.” Row, battling a mixture of fear and weariness, imagined lifelike forms in every rock, but he kept reminding himself not to fire at what he hoped were only illusions.

Teters excused 186 men to fight with the Marines while keeping them on the payroll of Morrison-Knudsen, the civilian contractor that had hired them, and over 400 civilians—the “citizen soldiers” of 1941—ultimately helped in one form or another.

Meanwhile, citizens back home closely followed the Wake saga. Men jammed enlistment centers to join the military, including five Waterloo, Iowa, brothers named Sullivan, who later died together on the same stricken ship off Guadalcanal. In its December 22 issue TIME magazine trumpeted Wake’s feats, stating, “They had been there since the first day of war, beating off attack after attack by the Jap, shooting down his planes, sinking his surface ships, probably knocking the spots out of his landing parties.”

Then came one of those moments that elevated Wake to heights few battles attain and contributed to the legend that formed. As reported in TIME magazine on December 29, 1941, “From the little band of professionals on Wake Island came an imprudently defiant message phrased for history. Wake’s Marines were asked by radio what they needed. The answer made old Marines’ chests grow under their campaign bars: ‘Send us more Japs.’”

The phrase was precisely the tonic needed by a country weary of defeat. Patriotic pride and enthusiasm bubbled over these words, supposedly uttered by Devereux when asked by Pearl Harbor what they could do for him.

In fact, those words had never been spoken. They were simply added as padding at both ends of a coded radio transmission to confuse Japanese cryptanalysts. Someone at Pearl Harbor extracted the phrase and turned it into the national rallying cry it became. American citizens learned after the war that Devereux had never used the words, but by that time the impact had long had its effect.

While citizens in the United States cheered the phrase, Marines on Wake jeered when they learned of the incident. “We heard about the quote, ‘Send us more Japs,’ while we were on Wake,” explains Private Ewing E. Laporte. “We didn’t like it at all.” The last thing any Marine wanted was more of the enemy.

What they needed was more aircraft. On December 22, the final two fighters were destroyed in combat. With their air umbrella gone, the Marines became the sole line of defense. Without ships, without planes, without relief, the Marines stood in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, surrounded by an enemy that burned with a desire to seek vengeance for December 11.

From behind the sandbags of his hastily fashioned gun emplacement, Marine Corporal Ralph Holewinski wondered how he and his buddies would turn back a well-equipped Japanese task force. In the movies he watched back home, the good guys always won. But at that moment he asked himself, “Where’s the cavalry now?”

Hopes that the Navy would speed to their rescue alternately soared then plummeted during these 12 days. Each time the cycle unfolded without help arriving, the sense of isolation gripped Wake more tightly.

Wake’s Marines expected the Navy to come to their aid. After all, that is what fellow servicemen do. Commander Cunningham wrote, “We felt good, almost cocky. Surely, help would come from Pearl Harbor any day now, and meanwhile we could wait it out.”

In fact, at Pearl Harbor, Kimmel had already prepared a daring plan to relieve Wake, centering on the aircraft carrier Saratoga. In the aftermath of December 7, however, Kimmel was quickly replaced by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz.

Until Nimitz arrived from Washington, Vice Adm. William S. Pye, a man as cautious as Kimmel was daring, held the reins. Pye dreaded losing any more of the battered Pacific Fleet before Nimitz assumed command and thus acted with reticence toward anything that might endanger the ships. However, he reluctantly permitted the relief expedition, carrying 200 Marines, 9,000 rounds of 5-inch shells, and a squadron of aircraft, to steam out of Pearl Harbor on December 12.

Back on Wake, Marines impatiently watched and waited. “Why the hell doesn’t somebody come out and help us fight?” Captain Elrod asked Major Devereux. Many civilians, certain that the Navy would evacuate them before the Japanese arrived in force, made plans to depart. Their optimism seemed justified on December 20, when Ensigns James J. Murphy and H.P. Ady landed a seaplane in Wake’s lagoon and brought news that the relief expedition, due to arrive Christmas Eve, was already heading toward Wake. Every Marine brimmed with confidence that they could hold out for four more days.

Stranded And Alone

Meanwhile, Murphy and Ady prepared to fly out. Since Major Walter Bayler had orders to proceed to Midway at the earliest possible time, he joined the ensigns on the outward flight. Before leaving, Bayler told the other men he would forward any letters they cared to write to loved ones.

Men penned letters to wives or parents, informing them that they were well and not to worry. “To Mrs. Luther Williams, of Stonewall, Mississippi,” wrote one Marine. “Solon is OK. Tough fight—but OK.”

Cunningham wrote his wife, “You know I am waiting only for the time of our joining. Circumstances may delay it a little longer, but it will surely come.”

Others declined. “We got the word to write a letter if we wanted to, and our corporal said he’d take them down from our station,” explained Laporte, “but I don’t think anybody there wrote a letter. I think a lot of us didn’t know what to say.”

On December 22, Pye, concerned that Japanese carriers might be in the area and worried that he might lose the few remaining ships of the Pacific Fleet, recalled the relief expedition. The recall produced angry outbursts among Marine and Navy personnel aboard the ships at sea, who urged superiors to ignore the order and continue on to rescue their fellow fighters.

The language grew so inflammatory on the bridge of the Saratoga that Rear Adm. Aubrey Fitch stormed off so he would not hear possibly mutinous talk and be forced to take action. One Navy officer aboard the carrier Enterprise dejectedly wrote, “It’s the war between two yellow races.” Even in Japan, propagandist Tokyo Rose ridiculed the Navy by sarcastically asking in a broadcast, “Where, oh where, is the United States Navy?” The order stood, however, and the task force reluctantly turned away from Wake.

Wake’s defenders were now completely alone. They did not learn of the recall until much later, though, for they were now heavily occupied with problems of their own. On that same day, Japan launched the second landing attack.

Admiral Kajioka took few chances this time. Four heavy cruisers escorted 2,000 men, and the aircraft carriers Soryu and Hiryu, returning from their victory at Pearl Harbor, provided air support. To avoid the damage sustained in the prior attack, Kajioka ordered his ships to remain beyond the range of Wake’s accurate shore batteries.

Devereux spread his mixture of Marines, Navy personnel, and civilians throughout a 4.5-mile defense line that ran along Wake Island’s southern shore. Machine-gun crews dug in at each end of the airfield, while other defenders manned their positions and waited for the attack to begin. In case the Japanese broke through the line, Devereux organized the only reserve force he could muster, eight Marines and four machine guns in a truck.

In the early-morning stillness of December 23, the Americans gazed seaward with a fierce determination that had outlasted the tortuous days of bone-rattling bombing. “I noticed a strange thing,” wrote Devereux. “It was an unspoken thing, intangible, but it was as real as the sand or the guns or the graves. My men were average Marines, and they had bitched and griped among themselves like any soldiers. Now their nerves and bodies had been sapped by two almost sleepless nights. Now the chips were down for the last roll of the dice, and they knew it, and they knew the odds were all against us, but now they were not grumbling. There seemed to grow a sort of stubborn pride that was more than just the word ‘morale.’”

Ewing Laporte sensed a difference as well. As the surf crashed against Wake’s shores and a stiff ocean breeze wafted the smell of salt water among the anxious defenders, the Marines waited with a new attitude. “There was that look on their faces. They weren’t the same guys anymore. It wasn’t a desperation look, but a look you got when you knew you had to do something. Of course, there was some fear involved, but every damn one of ’em was ready to do his duty.”

While many civilians sought shelter from the fighting in the brush, some hardy souls lent their assistance. John P. Sorenson, a large, hard-edged construction worker over 50 years old, led a group of 22 civilians to a command post to offer assistance to the Marines. The officer, touched by their willingness to fight, knew their chances of surviving combat were slim and declined their offer. Sorenson smiled and replied, “Major, do you think you’re really big enough to make us stay behind?”

As usual, a pre-invasion bombardment tore into the thin lines on Wake. Platoon Sgt. Johnalson E. “Big” Wright, an immense man weighing 320 pounds whose ability to down copious amounts of beer was legendary, stood in the open as bombs exploded, tightly clutching in his hands the lucky silver dollar he had carried for years. Other men begged him to seek shelter, but Wright counted on his lucky dollar to pull him through. Just as he was again telling the men to shut up, an explosion engulfed him. The dead Marine lay on the beach, still cradling the silver dollar.

The Japanese Invade

Around 2 am Japanese soldiers landed in three places on Wake Island and the adjoining Wilkes Island. They rushed forward with fixed bayonets, determined to shove the defenders out of their places and overrun Wake. Devereux’s communications with his outposts quickly broke down, due either to faulty wire or to being cut by the enemy. In the dark and without communications, Devereux could obtain no clear picture of the fighting, but he correctly guessed the location of the main thrust and ordered his small reserve force to the middle sector.

Marines and civilians fired their weapons until the Japanese were on top of them, at which time they resorted to bayonets and bare hands. Major Paul A. Putnam, knocked to the ground in the melee, fired his .45 pistol at two Japanese soldiers at such close range that one slumped dead across him. A Japanese soldier saw one Marine “blaze away with a machine gun from his hip as they do in American gangster films.”

“Two civilians—Paul Gay and Bob Bryan—were killed alongside of me,” explained Ralph Holewinski, still touched by the heroism of men who were not on Wake to fight. “As the Japanese moved closer to our gun emplacement—within 20 feet, close enough that when I hit one he spun around and the blood spurted out, just like in the movies—Bryan kept lobbing grenades from a box he tightly clutched.” After the battle, 30 Japanese bodies lay sprawled around the position defended by Holewinski and his civilian comrades.

John Sorenson and his men fought side by side with the Marines in another foretaste of the “citizen soldiers” who would shortly be entering the service to augment the regular military forces. The killing and maiming occurred from close quarters as opponents smacked into each other, clutched throats, bit hands, screamed in pain, and died with sudden violence. As Japanese soldiers advanced toward Sorenson’s position, bullets spitting from their rifles and hand grenades plopping into foxholes, Sorenson ran out of ammunition. Without hesitation he rose from his position, ran toward the enemy, and hurled expletives and rocks until felled by bullets.

Marine aviator Captain Henry T. Elrod had earlier distinguished himself by sinking a Japanese destroyer on December 11, but his actions on December 23 earned the career officer a posthumous Medal of Honor. Reporting as a combat soldier after all the aircraft had been destroyed, Elrod stood with his fellow defenders as the Japanese swarmed toward them. Accurate American fire cut down swaths of enemy soldiers, but more quickly took their place. Marines and civilians died amid a hail of bullets and grenades, some grappling with their foe in brutal hand-to-hand combat.

“Enemy on Island—Issue in Doubt”

Looking like the classic image of Davy Crockett surrounded by Santa Ana’s troops at the Alamo, Elrod stood up in the midst of the fighting, shouted “Kill the sons of bitches!” and blasted away with his Thompson submachine gun. When that weapon ran out of bullets, Elrod picked up a Japanese machine gun and continued to fight. Finally, with Japanese bodies piling up at his feet, Elrod was killed as he prepared to toss a hand grenade.

In numerous spots, other fighters recorded unheralded deeds. Gunner Clarence B. Mc-Kinstry rallied his small group by shouting, “Get going, move on! You don’t want to stay here and die of old age!” As the men rushed forward, McKinstry tossed hand grenades passed to him by an accompanying civilian. When he saw a supposedly dead Japanese soldier rise from the sand and kill an American, McKinstry bellowed, “Be sure the dead ones are dead!” Marine Corporal Alvey A. Reed and a Japanese attacker charged headlong in the melee, simultaneously plunged their bayonets into each other, and slumped to the ground, locked in a deadly stillness as the noise and fury continued about them.

In spite of the valor, the small group of defenders could only hold on for so long against the much larger enemy force. Although cut off from forward positions since communications lines had been severed, Devereux knew the defense was being overwhelmed. When a civilian rushed inside, screeching in terror, “They’re killing them all!” Devereux decided to establish a last-ditch defensive line near his command post and manned it with clerks and communications personnel.

With the battle deteriorating, Commander Cunningham realized that further resistance was futile. At 5 am he had sent a message to Pye, stating, “Enemy on Island—Issue in Doubt.” Now, two hours later, he turned to Devereux and muttered, “Well, I guess we’d better give it to them.” Cunningham then headed to his room, shaved and washed his face, put on a clean uniform, and headed out to meet the enemy.

For one of the few times in Corps history, a group of Marines was surrendering to an enemy.

Devereux Surrenders

The end of the fighting, just as the beginning, was orchestrated by Major Devereux, who stepped forward to arrange the surrender details. The heavy burden showed on the career officer’s face, and Sergeant Bernard Ketner consoled him at the command post, “Don’t worry, Major. You fought a good fight and did all you could.”

Devereux walked out into the open to pass the order along to different units. When one Marine questioned him, Devereux snapped, “It’s not my order, damn it!”

At Peacock Point, Franklin Gross at first refused to believe the fight had ended. “We were raised up in the school that Marines never surrender and the Japs would never take us prisoners. I sent one of my men over to the 5-inch guns, and he climbed up in the observation tower and he couldn’t see any Japs.

“We took off down a path there, about 12 men. One of the guys found a can of pineapples, and we were eating it when we heard a shot. I don’t know whether this guy shot into us or over our heads, but I looked up and here were these Japs wearing all this camouflage and these hats. We had a white flag with us. They took us a little farther up and stuck us in the brush and made us sit down. They set up a machine gun in front of us, and knowing what I had heard and read about the Japs all these years I knew they were going to kill us.

“I stared at the gun barrel and knew as well as I was going to take another breath that they were going to kill us. I looked right at that barrel and thought, ‘Well, I’m going to see you spit your fire.’

“I didn’t say a prayer—you were beyond praying. You had to rely on yourself. If anyone was going to help you, it had to be you.”

Meanwhile, Ewing Laporte endured his own little hell. He watched Major Devereux and another officer, holding a mop to which was attached a white rag, walk over and order Laporte’s group to surrender. After the fighting and dying, the shouting and the bombs, now the men were to lay down their weapons.

“I didn’t believe that we were surrendering. I threw the bolt of my rifle away to make it useless for the Japs, then saw some Japanese on the road. It was the shock of my life to see them. They jerked our clothes off, took our rings, tied us up. They were small, but it don’t matter what size you are as long as you got a rifle.

“We hated this. Can you imagine! Our creed was supposed to be you don’t surrender, but we had the order. It was hard to take.”

A High Price for Japan’s Forces

After completing the exhausting duty, which was more difficult for Devereux than any he had carried out in his career, he collapsed to the ground in despair. Just then a haggard group of Marine prisoners trudged by, guarded by Japanese soldiers. One Marine, Sergeant Edwin F. Hassig, spotted his commander and barked to his men, “Snap outta this stuff! Goddamn it, you’re Marines!” The Marines quickly straightened up and marched by Devereux in perfect formation.

Heartened by the sight, Devereux regained his composure and stood at the head of his Marine contingent. Some of the other men checked impulses to charge at the Japanese, who by now were running all about the camp, ransacking barracks and cheering in delight. When one Japanese soldier climbed the tower to lower the American flag, a few Marines took a step forward, but Devereux nipped any foolhardy actions. “Hold it. Keep your heads, all of you!” In angry silence, they glared at the solitary enemy soldier who tore down the Stars and Stripes.

They had no reason to be ashamed, for the defenders of Wake exacted a high price for the island. Forty-nine Marines, three Navy personnel, and 70 civilians died in the melee, while the Japanese lost two ships and seven aircraft and suffered at least 381 dead.

The Japanese tied each man’s hands high behind his back, with a wire looped around the neck. Any lowering of the arms tightened the wire, so each man battled pain and the sun to keep his arms elevated. After a few agonizing hours, the Japanese cut the bindings and ushered the men to the airstrip, where they detained them without food and water. “We got no food or anything for a while,” mentioned Laporte. “Christmas dinner was bread and jam. December 26 we had some food and we were marched into the barracks.”

Admiral Kajioka’s chief of staff approached Devereux to ask where the hidden gun positions rested. When Devereux replied there were none, that the only gun positions on Wake were the visible ones, the Japanese officer refused to believe that so few guns had inflicted such damage. Another Japanese officer asked Cunningham if Wake had actually sent the famous message, “Send us more Japs!” When Cunningham replied in the negative, the officer answered, “Anyhow, it was damned good propaganda.”

On January 12, 1942, all the Americans, except for a group of civilians who remained on Wake as laborers, boarded transports for the long voyage to Asian prison camps. Before the transports reached their destination, the Japanese selected five Marines, led them on deck, and beheaded them as retribution for the fighting on Wake. Similar angry actions would become all too commonplace for the Wake defenders.

After seizing Wake the Japanese stationed on the island were cut off from their homeland by the steady American advance through the Pacific. Supplies ran out, forcing the Japanese to eat grass for sustenance, and daily bombing made life miserable on Wake. People in the United States never forgot the Battle of Wake Island and the valorous deeds performed there, but Japanese civilians and military officials gave little notice to the soldiers garrisoned on the island.

The Japanese suffered quietly, ignored by their own government, until war’s end, at which time the United States returned and reclaimed the land. Partly out of a spirit of vengeance, on October 7, 1943, the hundred civilian construction workers still on Wake were bound, blindfolded, led to the beach, and machine-gunned to death.

Four hundred Marines, five Army and 65 Navy personnel, and 1,076 civilians eventually left troop transports and slowly marched through the gates of Asian prison camps that were to be their homes for the next three and a half years. While they endured misery and hardship after performing bravely in the battle, the Wake defenders do not think they are heroes. At Wake and in prison camp they simply did their job—no more, no less.

Surviving the Camps

“People always say we’re heroes, and to most Wake Islanders it’s embarrassing,” explained Gross. “You know, any other group of Marines with the same amount of experience would have done the same thing. It’s no small thing we did, because we probably delayed the Japanese going to Midway about 30 days. They had to go back and regroup, and it took them 16 days to take Wake, so it slowed their timetable. It was quite a feat, but any other bunch of experienced Marines would have done the same.”

Gross may be right, but the Wake Island defenders, military and civilian alike, were extraordinary individuals. In times of stress they turned to one another, leaned on each other, and maintained faith that each would do his duty.

They also clutched tightly to another faith. At a reunion 40 years after the attack, the author asked LeRoy Schneider what made him survive prison camp when others did not. The imposing Wake Marine, still muscular and dignified after all these years, answered with a few simple, yet moving, words. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a well-worn Rosary that looked as if it had been used thousands of times.

“It was this,” he said to me as he nodded toward the string of beads, the same one he had used in prison camp. “Each Sunday a group of us, including Major Devereux, gathered together, got down on our knees, and said the Rosary.” As tears welled in the aged warrior’s eyes, Schneider added, “That’s what got me through.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments