By David J. Little

After the Great War, in which American troops were sent into combat with either the bolt-action M1903 Springfield rifle or the bolt-action British Enfield, planners in the War Department realized that, if the United States were ever drawn in combat again, they would need a far superior weapon.

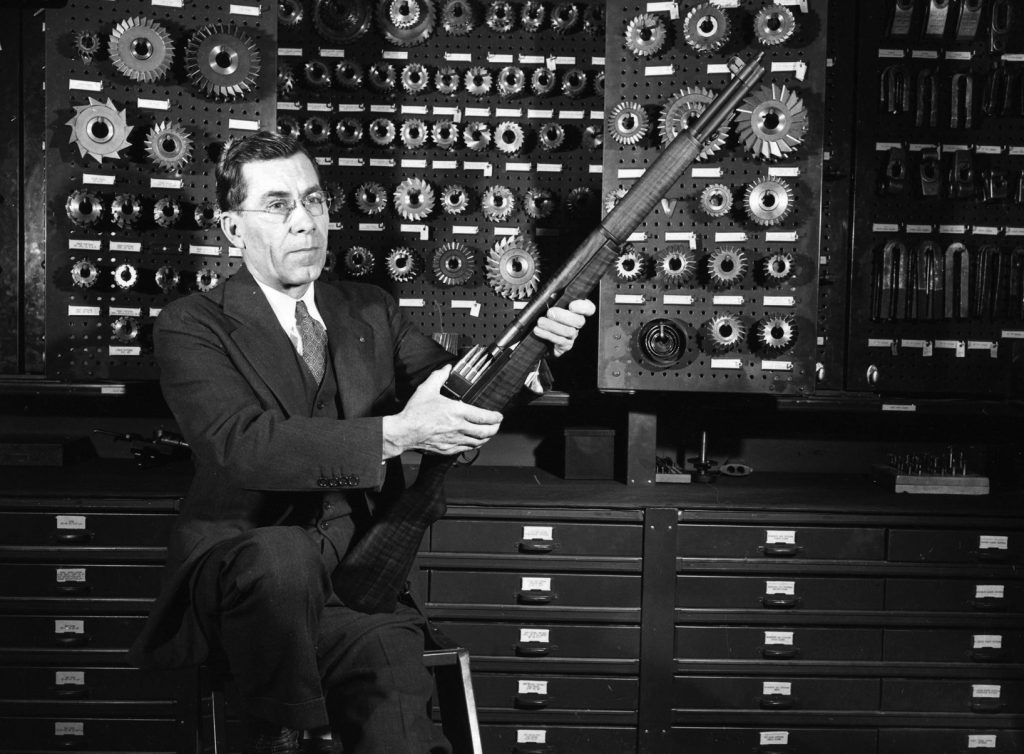

The M1 became one of the most popular of all military weapons. Per Army specifications, the rifle would be a long-stroke gas piston-operated, eight-round, clip-fed rifle that used the same .30-06 cartridge as the ’03 and Enfield.

In 1924, one of Springfield’s engineers, Quebec-born (in 1888) John Cantius Garand, began working on a concept for a lightweight semi-automatic rifle. In 1934, what became the M1 was patented by the Springfield (MA) Arsenal (which began making military firearms during the Revolutionary War) and two years later a contract was awarded to Springfield, which would eventually turn out 4.5 million copies.

To meet the demands of World War II, Winchester Repeating Arms received an order for five million more; production of the M1 ended in the 1950s when the M14 replaced it (from 1959 to 1964).

The M1s were initially issued to regular Army units but at the outbreak of the war in December 1941 and for some months afterward, National Guard and U.S. Marine Corps units were still using the World War I Springfield ‘03s.

What made the .30-06 M1 Garand revolutionary for its time was the fact that it was semi-automatic, which means that it would continue to fire each time the trigger was pulled, until the clip was empty.

This was due to a gas port drilled into the bottom of the 24-inch barrel near the muzzle. When a round was fired, the gases built up in the barrel were channeled back toward the receiver (through what looks like a second barrel), where the gas automatically ejected the spent cartridge and the mechanics of firing seated a new one.

To fire the M1, the rifleman pulls the operating rod handle to the rear where it engages a catch, keeping the chamber open when the last round is fired. A full clip can then be inserted through the top of the receiver and pressed down with the thumb while the heel of the hand is used to hold back the bolt handle; the thumb is then quickly withdrawn. If not done correctly, the bolt will automatically release and slam forward (with such force that it can cause a painful condition known by soldiers as “M1 Thumb”), as the first round is shoved into the barrel.

To fire the M1, the rifleman pulls the operating rod handle to the rear where it engages a catch, keeping the chamber open when the last round is fired. A full clip can then be inserted through the top of the receiver and pressed down with the thumb while the heel of the hand is used to hold back the bolt handle; the thumb is then quickly withdrawn. If not done correctly, the bolt will automatically release and slam forward (with such force that it can cause a painful condition known by soldiers as “M1 Thumb”), as the first round is shoved into the barrel.

In training and combat, the M1, because it did not need to be removed from the shoulder in order for its bolt to be pulled back to eject a spent cartridge, the soldier could maintain a reasonably accurate “sight picture” of his target and not have to completely reacquire the target between shots.

The Army rated the rifle as accurate up to 450-500 yards in the hands of a proficient marksman. The M1 front blade sight was fixed but the rear sight could be adjusted in 25-yard increments and there was a knob to make “windage” adjustments. The amount of recoil was not excessive, although soldiers were advised by their rifle-range instructors to press the stock closely against the cheek and shoulder.

Although not heavy by Browning Automatic Rifle M1918 standards (which weighed 16 pounds empty), the M1 was no featherweight. Scaled at 10.5 pounds empty with its walnut stock and leather or canvas sling, plus the cleaning kit installed in its butt stock, the rifle was easy for the average soldier to carry (although some complained that it inexplicably got heavier as the day wore on, especially on long marches during basic training). The Colt 5.56mm caliber M-15 rifle (derived from the Armalite AR-15) introduced during the Vietnam War, weighs about 6.37 pounds empty.

Like any weapon, the M1 could become inoperable if mud, ice, rust, or other debris got into any of its moving parts. Therefore, soldiers were constantly implored to keep their weapons clean and well lubricated.

One disadvantage that many soldiers complained about in combat was the loud metallic “ping” that emanated from the weapon as it flung its empty clip into the air. One soldier said, “You might just have well yelled out to the enemy, ‘Hey, I’m out of ammo for a few seconds.’” That being said, however, in the general din of battle, the “ping” was almost never heard by either friend or foe.

During the Korean War in the 1950s, International Harvester and Harrington & Richardson of Ilion, New York, were also awarded contracts to produce M1s.

The Germans also developed their own semi-automatic rifles in the early 1940s.

Called the Mauser Gewehr 41(M) and the Walther Gewehr 41(W), these weapons suffered from reliability problems that limited their usefulness on the battlefield. They were replaced by the Berlin-Lübecker Maschinenfabrik Gewehr 43, renamed the Karabiner 43 in April 1944; a total of just over 400,000 were produced before the war’s end.

After the war, the United States sold or loaned most of its M1 arsenal to other countries as the American armed forces switched first to the M14 (with a 20-shot magazine and 7.62x51mm NATO-standard ammunition) and then the AR-15 as the standard rifle.

The government-run Springfield Arsenal closed in 1968 but a private company, licensed to call itself Springfield Armory, Inc., began operations at its Geneseo, Illinois, facility. Using the exact blueprints and identical specifications as the original Springfield Armory, the company today manufactures M14 rifles and M1911 .45 caliber pistols.

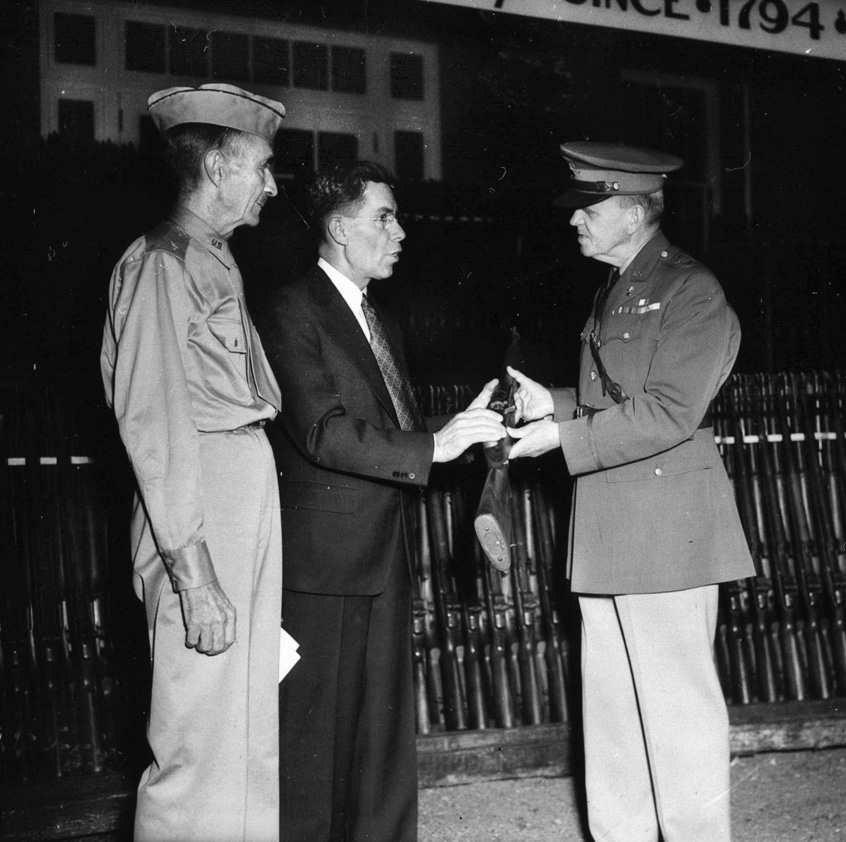

Today a used M1 Garand can be purchased for as little as $500-$1,000, although an M1 National Match M1 Garand once presented to then Senator John F. Kennedy in 1959 sold at auction in 2015 for $149,500. Another, previously owned by Mr. Garand himself (it was a gift at his retirement ceremony in 1953), sold in 2018 at Rock Island Auction for $287,500. It bears serial number one million. Many M1s can be purchased today through the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP).

As one M1 Garand enthusiast said, “It is not a perfect weapon, but the rifle’s legend is woven into the fabric of our nation.”