By Phil Zimmer

A wily British scientist, a secret weapon, and a daring daytime Bombing raid helped break the back of the deadly German E-boat attacks on the Allied ships that supported the early D-Day landings at Normandy.

Real-time breaking of top-secret German codes and modern-day analytics were central to the little-known but crucial June 14, 1944, raid against the Nazi naval base at Le Havre, just east of the Normandy beaches.

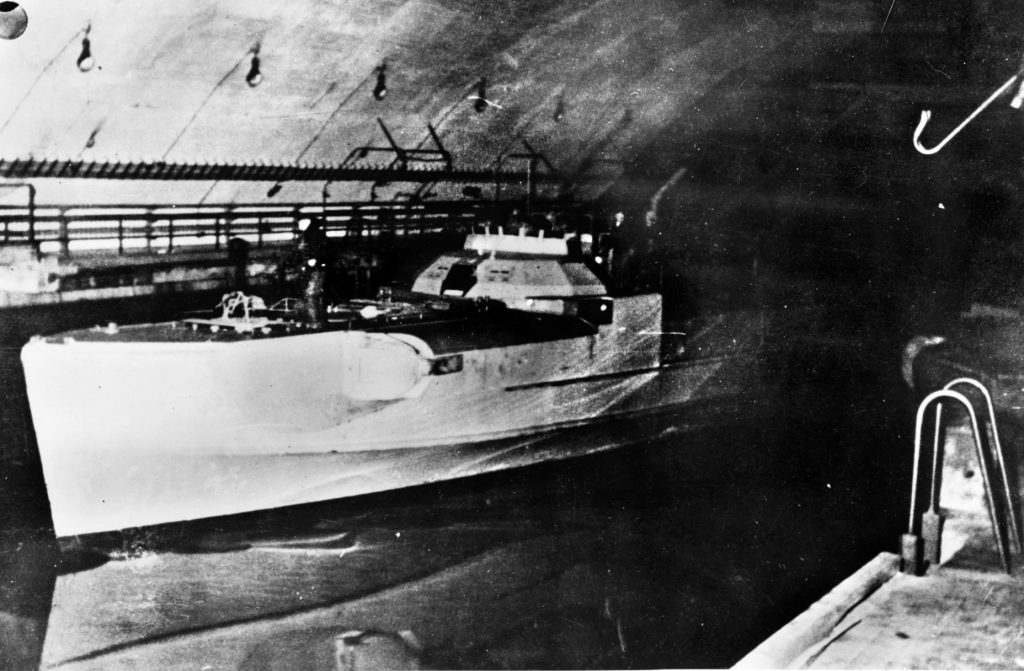

A total of 337 Allied aircraft were committed to the initial raid; these included 22 Avro Lancaster bombers from the prestigious Royal Air Force No. 617 “Dambusters” Squadron, which dropped the secret 12,000-pound “Tallboy” bombs onto the concrete-hardened pens the Germans had built to protect their naval assets. The devastating raid was the largest by Britain’s RAF Bomber Command since the war had begun almost five years earlier.

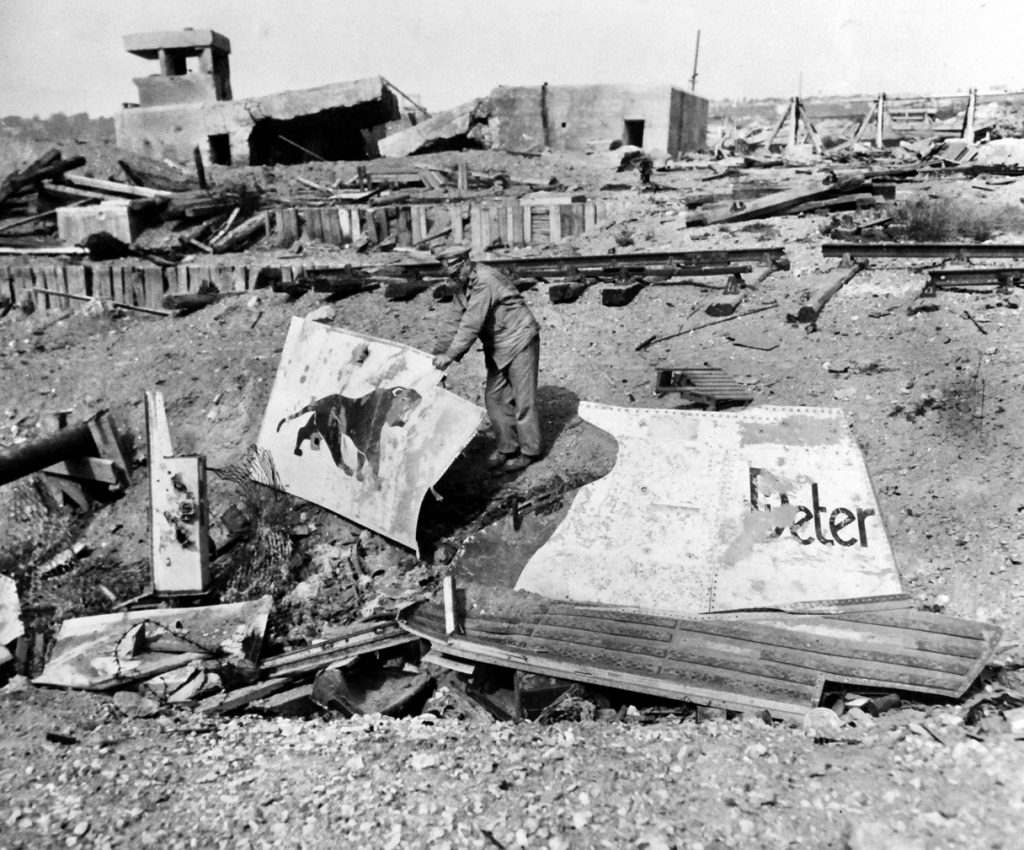

The attack created several fires, and debris was scattered everywhere in the port. German rescue and firefighting work was well underway when, two hours later, another flight of 119 Lancasters appeared overhead and pounded the harbor in a second surprise bombardment.

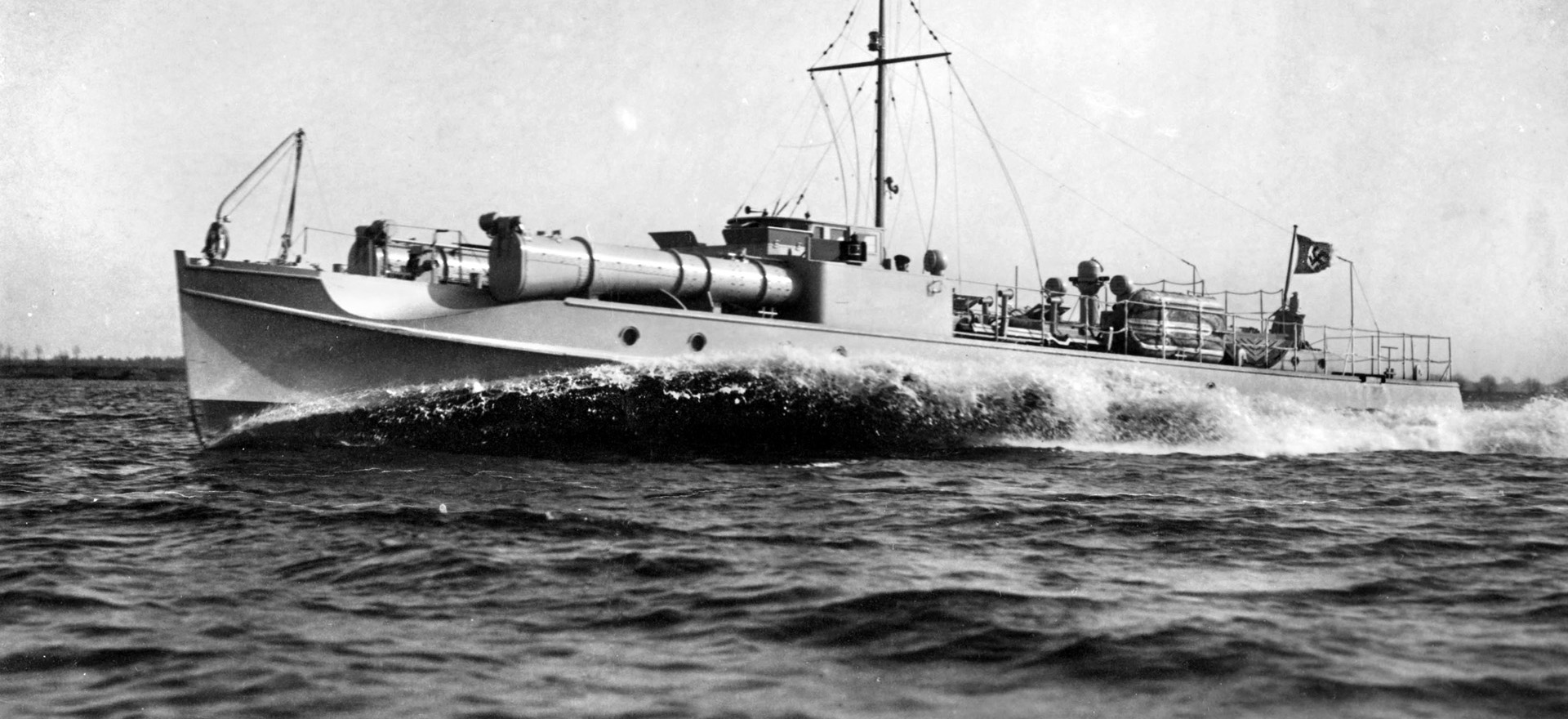

The British estimated the Germans lost 38 vessels sunk and another 31-34 ships damaged. These included 10 E-boats (called Schnellboots by the Germans) sunk by direct bomb hits, three more so damaged they were beyond repair, one beached, and another with its bow blown off. Only one remained combat-ready.

The covered pens, heavy, concrete shelters designed to protect naval craft, were easily penetrated by the powerful Tallboys. Even those new bombs that missed their marks often created “tidal waves” inside the confined pens, which tossed the German vessels about and created substantial damage. Intercepted German reports confirmed the extensive damage, which included the sinking of three torpedo boats, another heavily damaged, and one of the sunken boats blocking the pens. The Kriegsmarine also lost additional war vessels, including dozens of smaller minelayers, minesweepers, patrol vessels, harbor launches, tugs, and a huge floating dock to the carnage wrought by the Tallboys.

The fierce attack on a naval site, unprecedented to date in the war, also destroyed warehouses, uprooted all the crucial cranes in the harbor, blocked vital access roads, and took out the port’s only torpedo-loading facility. In addition, all the torpedo warheads stored at Le Havre were destroyed. Some 200 German naval officers and men were killed, and another 100 were seriously wounded.

The Germans quietly admitted the raid was catastrophic, while the Allies rightly believed that it ended “effective E-boat opposition in the English Channel.” Bomber Command had scored an impressive win. To back things up, the very next night the Brits launched a similar, but initially smaller, attack on the port of Boulogne, with a follow-up blanket raid there by 300 Lancasters. Thirty-one ships, including a number of minelayers, were sunk and nine other vessels damaged.

Both attacks used the new Tallboy bombs and clearly demonstrated that the Kriegsmarine could no longer rely on hardened pens to protect their boats. The pens, in fact, had become magnets for attracting undue attention on the part of the destructive Tallboys. Admiral Theodor Krancke, German naval commander in the West, assessed the situation and said the “heavy losses completely put an end to our offensive operations in the second week following the invasion.”

Some remaining E-boats did continue to make runs from other ports, but their ability to swarm over and disrupt shipping in the Channel was substantially lessened as the result of the raids. This enabled the Allies to continue to send men, weapons, and related supplies largely unimpeded to the crucial Normandy beachheads.

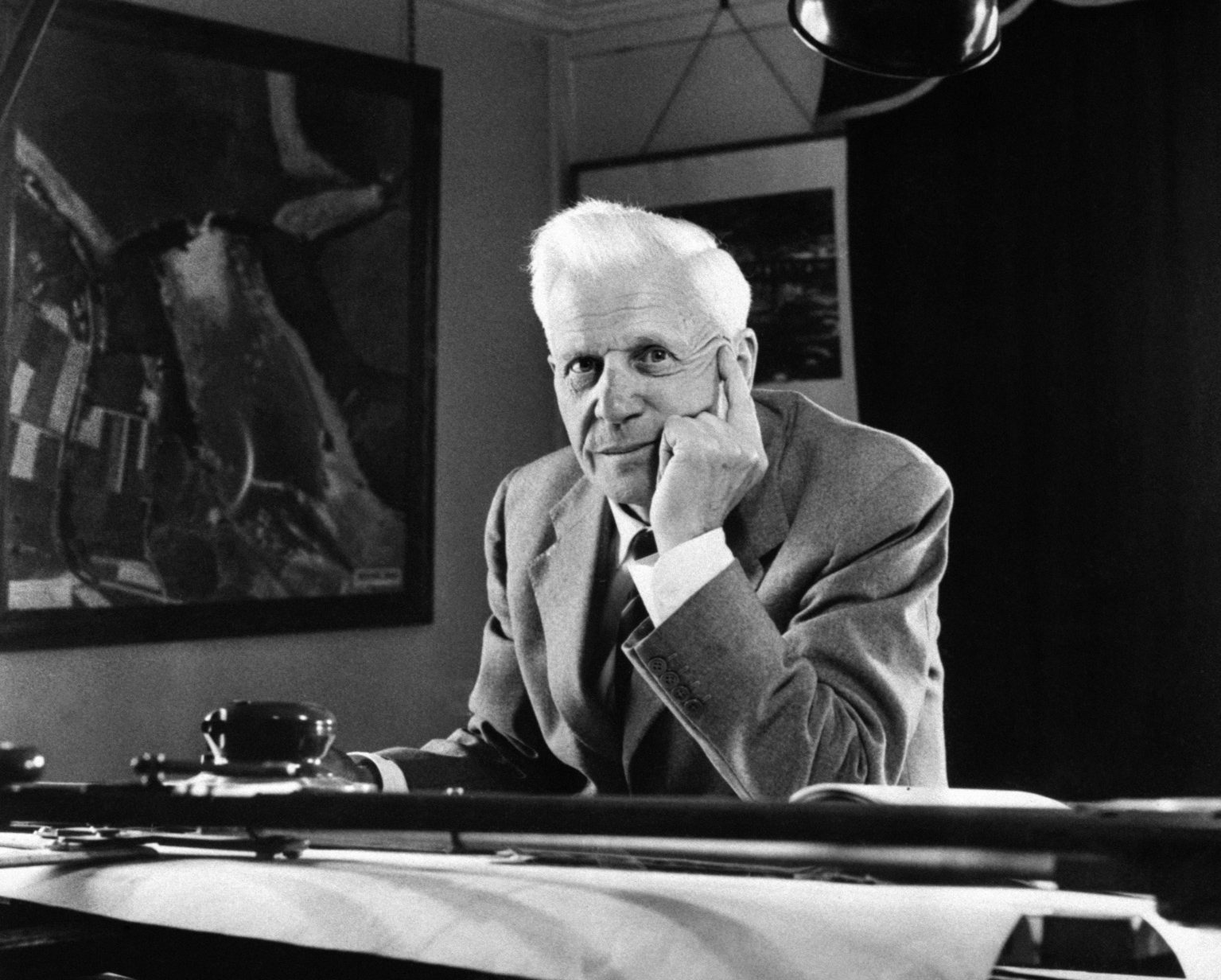

Several individuals contributed to this development, including a brilliant innovator named Barnes Wallis. The engineer had made a name for himself with the interwar development of the Vickers Wellesley and Wellington Bombers. The latter plane proved itself so capable that it was used well into World War II.

With World War II looming on the horizon, Wallis began to consider the use of a big bomb to destroy sites protected by concrete embedded in earth or surrounded by water. Such a large bomb, he theorized, could produce shockwaves around a target to bring it down. He envisioned it as a large, steel-encased, 10-ton bomb dropped at 40,000 feet with newly developed methods so it would slam into the earth at supersonic speeds and “burrow” deep into the surface and explode beneath the target. The shockwaves would travel upward, shatter the hardened concrete, and cause it to fall into the cavity created by the explosion.

Wallis initially met resistance because the British lacked a bomber capable of handling such a weapon and because studies revealed an inability to hit a target with the precision necessitated by such a bomb.

The researcher nevertheless continued with development of a thin-skinned bomb that could explode underwater against a target like the wall of a dam. Here, the explosion in the water would create shockwaves and bring down the structure, he theorized. He submitted a proposal along those lines, and on the night of May 16-17, 1943, Lancaster bombers dropped the four-ton cylindrical “bouncing bombs” behind the Mohne and Eder gravity dams near the Ruhr, the industrial heart of Germany. The four-ton bombs skipped over torpedo nets and sank some 30 feet before being detonated by hydrostatic fuses. The shockwaves punched holes in the dams and created extensive flooding and a loss of water supplies for crucial industries in the Ruhr.

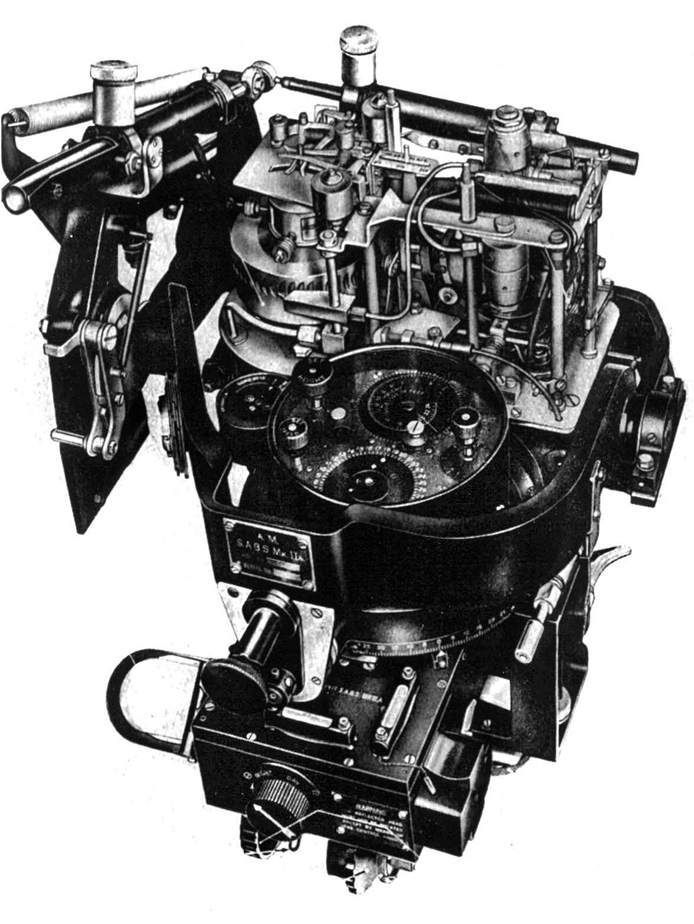

Squadron 617 executed the precise bombings, and the squadron would later be pressed into service at Le Havre and Boulogne to use further-improved aiming and bombing techniques along with the Tallboys designed by Wallis. The 617 had been equipped with an ingenious new device that one pilot aptly dubbed a “magic wand.” The Stabilized Automatic Bomb Sight (SABS) was a hand-built device somewhat like the Americans’ Norden bombsight, and No. 617 was the only squadron equipped with the craftsman-made device. The crews were strictly instructed to destroy them should their planes develop difficulties over enemy territory. That action would ensure that the enemy never got their hands on them.

The SABS had a telescopic sight mounted on a gyroscopically stabilized platform used by the bomb aimer, who was located in the nose of a Lancaster. The ingenious device generated corrections automatically while the aimer held the sight on the target. For it to work, there could be no deviation from course as the plane flew at its designated altitude and speed. Needless to say, this placed heavy demand on the crew, as they often headed through flak toward a target. This helps explain why No. 617 Squadron was generally used for only the most important bombing missions.

The Tallboys themselves came in three sizes: a 4,000-pound Tallboy S (small), a 12,000-pound Tallboy M (medium) and a staggering Tallboy L (large) that came in at 22,000 pounds and was produced in early 1945.

The initial testing of the Tallboy S models in December 1943 showed that when dropped from 20,000 feet, the bombs became unstable as they approached the speed of sound and ended up too far from the target. They also tended to disintegrate on impact rather than penetrate deep into the ground as intended. Wallis solved the problems with thickened steel in the nose and the use of fins to create a rapid spin to the casing. This gave the newly streamlined, 21-foot-long, three-foot-wide bomb the necessary ballistic stability as it approached Mach 1 and made it exceptionally accurate when coupled with the SABS.

The Tallboy S used torpex, a combination of 40 percent TNT; 42 percent RDX, a powerful new explosive; and 18 percent aluminum powder, plus other ingredients. The researchers had discovered that the aluminum powder enormously boosted the heat levels. They also found that sealing the mixture under pressure magnified the blast effect. Torpex, in fact, produced a higher blast level than any other standard explosive used in the war. The mixture had also proven itself earlier in the bombs used against the two dams in the Ruhr.

Squadron 617’s accuracy was aided significantly in the winter of 1943-44 with advances by the RAF’s Pathfinder Force (PFF). On the nights of January 24 and 25, 1944, the pilots of two pathfinder de Havilland Mosquito fighter bombers elected to ignore the prescribed altitude of 2,500 feet and swept in much lower to mark V-1 “buzz bomb” launch sites in the Pas de Calais region of France. The results were astounding, and the follow-up bombing by the Lancasters proved remarkably accurate.

These improved marking techniques helped pave the way for the devastating bombings of the Kriegsmarine at Le Havre and Boulogne. But other factors played significant roles as well. These included the breaking of the special Dolphin code used by the E-boats crews. The British were often able to read a Dolphin transmission within three hours, and occasionally within a half hour.

Using that information, they were able to better track where the E-boats were moored at any given time, thus bringing to an end the previous “whack-a-mole” efforts to put the marauders out of business. The Brits knew, with certainty, going into the raids on Le Havre and Boulogne that the boats would be in port, so they could go all-out to destroy them.

Another often-overlooked element came into play, as well: The Allies had recovered a number of E-boat crew members from the chilly English Channel after their craft were sunk. The young German sailors, disturbed by the quick departures of their comrades and warmed by British tea and apparent friendliness, often proved to be fountains of information on the scope and nature of the E-boat fleet. That information provided further details on the strengths and weaknesses of the enemy boats, as well as details on German torpedoes and mines.

In summary, the devastating raids on Le Havre and Boulogne proved instrumental to the long-term success of the D-Day landings, which were dependent on the continuing arrival of men, food, and equipment to support and expand the toehold on the Normandy coast. While the attacks did not fully knock the E-boat flotillas out of action, they did significantly lessen the impact of the boats on the long-term pursuit of the war. And it was a successful, cooperative team effort on the part of men like Wallis, the codebreakers, interrogators, and the dedicated crews of No. 617 Squadron, among others, that made the difference.

Author Phil Zimmer is a U.S. Army veteran and a former newspaper reporter. He has written on a number of World War II topics.