Amid the great assembly of senior Allied officers who stood by while the representatives of the Japanese government and those of the victors of World War II in the Pacific signed the instrument of surrender aboard the battleship USS Missouri on September 2, 1945, in Tokyo Bay, two of the most unlikely attendees waited solemnly to step forward.

General Douglas MacArthur presided over the ceremonies, and as he signed the document, he turned and presented the first pen to American Lieutenant General Jonathan M. Wainwright. The second pen was handed to British General Arthur Percival. These two officers had surrendered the Allied forces in the Philippines and Singapore, respectively, to the marauding Japanese in 1942. The gesture was a fitting but unlikely moment during the proceedings.

Wainwright, who had succeeded General MacArthur as commander of Allied troops in the Philippines when the latter was evacuated to Australia, went into Japanese captivity, first in the northern part of the island of Luzon, then on Formosa, and finally at Xi’an in the desolation of Manchuria. Wainwright was one of more than 80,000 American and Filipino soldiers surrendered with the fall of the Bataan Peninsula and the island of Corregidor in April and May 1942.

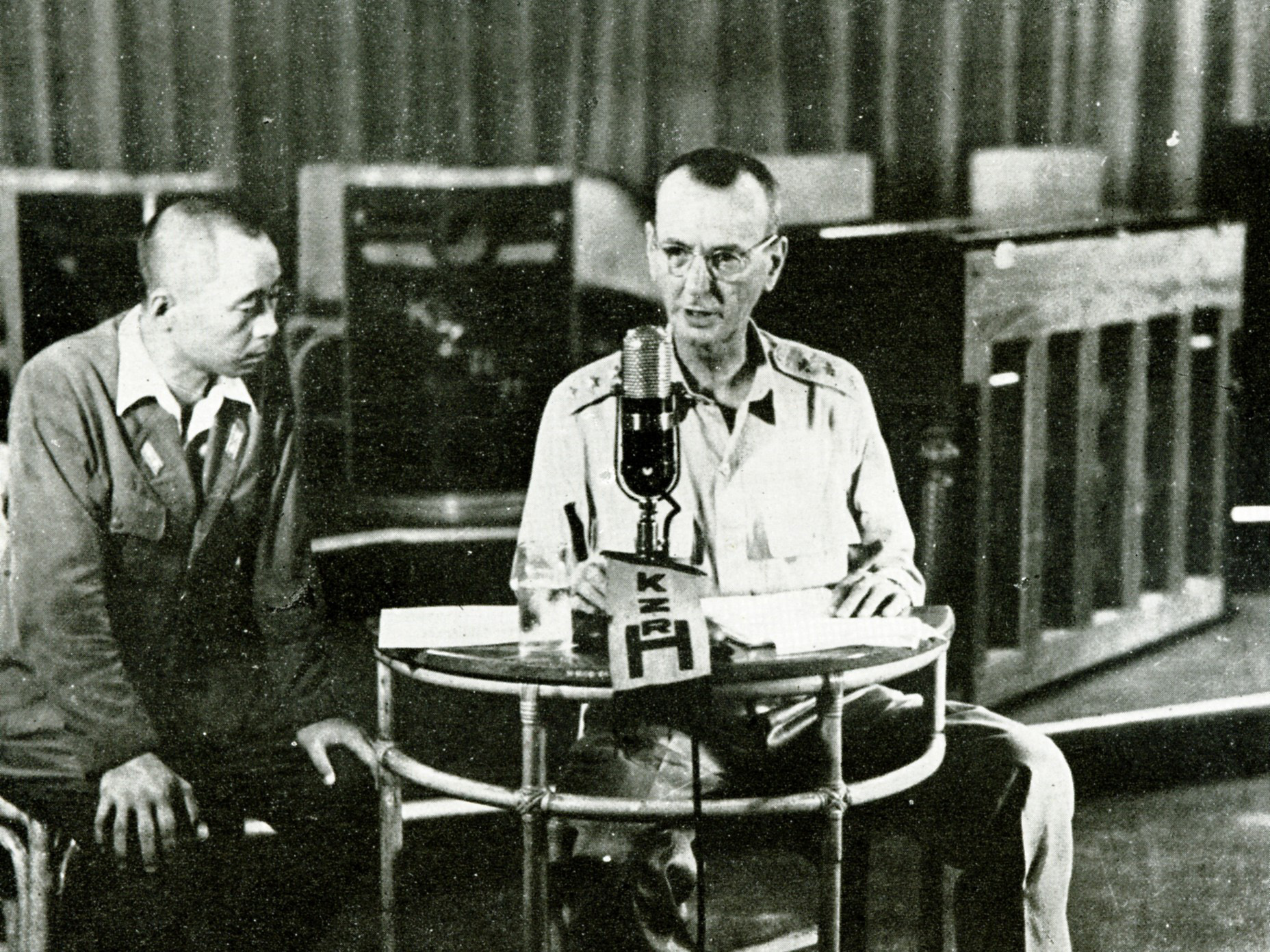

Despite being the highest-ranking American officer taken prisoner during the war, Wainwright endured the same starvation and ill treatment as his men. Already nicknamed “Skinny,” he lost considerable weight. While many POWs died in captivity, Wainwright managed to survive more than three years in Japanese hands.

The award of the Medal of Honor had been proposed for Wainwright as early as 1942. MacArthur, however, vehemently opposed it, believing that Corregidor should have held out longer and that Wainwright had surrendered too soon. In 1945, Wainwright was again proposed for the Medal of Honor, and this time MacArthur did not object to its presentation on September 19.

The citation lauds his heroism in command of the doomed defenders and reads in part: “…At the repeated risk of life above and beyond the call of duty in his position, he frequented the firing line of his troops where his presence provided the example and incentive that helped make the gallant efforts of these men possible. The final stand on beleaguered Corregidor, for which he was in an important measure personally responsible, commanded the admiration of the Nation’s allies. It reflected the high morale of American arms in the face of overwhelming odds. His courage and resolution were a vitally needed inspiration to the then sorely pressed freedom-loving peoples of the world.”

After he was freed by OSS operatives, Wainwright worried that he was considered a coward, derelict in his duty, by the American people. When he was informed that he was actually a national hero, the emaciated general was incredulous. Nevertheless, Wainwright returned to the Philippines and accepted the surrender of his former captors there. He was honored with a ticker tape parade in New York City on September 13, 1945, and promoted to the four-star rank of full general.

Wainwright later commanded Second Service Command and Eastern Division Command on Governor’s Island, New York. He took command of the Fourth Army at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, in early 1946, and retired from the Army the following year after 41 years of service. In civilian life, he served on several corporate boards of directors and became a Freemason. He died of a stroke on September 2, 1953, fittingly the eighth anniversary of the surrender ceremonies in Tokyo Bay. He was 64. His funeral was held on the lower level of the Memorial Amphitheater in Arlington National Cemetery, and he is buried there.

For the remainder of his life, Wainwright bore no grudge or malice against MacArthur or any other senior American commander involved in the decision to “abandon” his command to its fate in the Philippines. He never expressed disdain for MacArthur for opposing the award of the Medal of Honor in 1942, and in fact would have delivered the nominating speech at the 1946 Republican National Convention had MacArthur succeeded in securing the party’s nomination for President of the United States.

—Michael E. Haskew