By Pat McTaggart

The Siberians are coming!” It was a cry that spread terror through the ranks of the German Wehrmacht in the winter of 1941. Since June 22, the Red Army had lost millions of dead, wounded, and captured soldiers while the Wehrmacht had advanced to the very gates of Moscow itself.

Now, however, new armies seemed to be springing out of the Russian soil as if by magic as the Germans prepared their final thrust toward the Soviet capital. The ever-distrustful Joseph Stalin had primarily put his faith in the word of one man, and had ordered division after division of his armies in the Far East to be transported as quickly as possible to the west to blunt the German advance. That man’s name was Richard Sorge.

One of the Great Espionage Masterminds of the 20th Century

The story of Richard Sorge, one of the great espionage masterminds of the Soviet Intelligence Service, began on October 4, 1895, in Adjukent, a small village near Baku in what is now the Republic of Azerbaijan. Sorge was the youngest of nine children in a German-Russian household. His father, Adolf, was a German petroleum engineer who cut an imposing figure with his bearded face and piercing eyes. Mother Nina was a pretty Russian woman from whom Richard inherited his Slavic features of high cheekbones and slightly slanted eyes.

Sorge’s home life in Imperial Russia lasted for seven years until his father’s contract expired. The family then packed up and moved to the Lichterfelde section of Berlin. Coming from an upper-middle-class family, Richard attended a Berlin school at which he learned the basics required of all German boys of social standing. He excelled in many courses, such as history and political science, but tended to disregard any subject that did not interest him.

In 1911, Adolf Sorge died, leaving his family with enough money to continue living quite well. For the next three years, Richard continued his education, growing somewhat bored with his studies. Like many upper-middle-class teens in the early 20th century, he tended to find that many things in life had little or no purpose. All that changed with the assassination of Archduke Franz-Ferdinand on June 28, 1914. Within weeks, the Fatherland was at war.

The enthusiasm with which Europe went to war stirred the patriotic sense of the continent’s youth, and Sorge was no exception. Enlisting in the Kaiser’s army, he was sent to Belgium after a mere six weeks of training. The hell of the trenches soon extinguished the patriotic flame that had brought Sorge from Berlin to the miserable life that was the Western Front. Knee deep in mud and shivering in the cold, damp air of late fall, he began to question the validity of the war.

Wounded Near Ypres in World War I

Sorge also met a different class of people—men he would never have spent time with in Berlin society. Some were Socialists and others were radical leftists. As they talked about their own families and the persecution of the working class, Sorge began a slow transformation that would eventually lead him to his position of master spy for the Soviet Union.

In 1915, Sorge was wounded during the bloody fighting near Ypres in Belgium. He was sent home on convalescent leave but soon volunteered to return to the front. This time he was sent east, to the land of his birth. He arrived in Russia just in time to take part in an offensive that was tearing the heart out of the Russian Army. As the Germans advanced, Sorge saw the complete devastation that had been visited upon both the countryside and the people. Once again, he felt anxiety about the war. Here he was, fighting for his father’s country while destroying his mother’s.

The slaughter on the Eastern Front continued into 1916. Sorge was wounded twice that year, and his second wound sent him to a field hospital in Königsberg. It was there that he finally received his political awakening at the hands of a radical Socialist doctor and his daughter, a nurse. Under their tutelage, he became filled with revolutionary zeal. They persuaded the wounded soldier to pursue his studies, which he could do while on convalescent leave. Eagerly delving into history, economics, and philosophy, he became convinced that the war had no meaning. As the German economy began collapsing around him, he also decided that capitalism was the bane of the people. The loss of two brothers at the front only served to strengthen those convictions.

The Bolshevik Revolution & the German Communist Party

While Sorge was studying at Berlin University, the Bolshevik Revolution toppled the Russian government. The upheaval of society in his native land appealed to his newly found revolutionary spirit and, after being discharged from the army in 1918, he made his way to Kiel with the idea of spreading the Marxist ideology. Joining the Independent Social Democratic Party, he soon became an accomplished agitator as well as an instructor of Marxism.

Sorge became a member of the German Communist Party in 1919, while he was earning a Ph.D. in political science in Hamburg. His journalistic talents, which would provide him with a cover in the future, were honed while he served as an adviser to the Communist Party newspaper in the city. After a job in Aachen as assistant to Communist professor Dr. Karl Gerlach, Sorge decided to spread the revolutionary message by working in the coal mines of the Rhineland. The venture was short lived, however, after authorities discovered the young agitator.

In early 1921, Sorge was a political editorial writer for a communist newspaper in the Ruhr. The Communist Party at that time was under close scrutiny from government officials, and Sorge became an important liaison, carrying messages between Berlin and the party in Frankfurt am Main. Between his comings and goings, he also managed to find time to marry Christiane Gerlach, the former wife of his boss in Aachen.

April 1924 found Sorge assigned as a bodyguard for Soviet delegates who were attending a communist convention in Frankfurt. It was another turning point in his life. The position put him in contact with several prominent Russian communists who were impressed with his zeal for the movement, as well as his obvious intelligence and breeding. In fact, they were so impressed with the 29-year-old that they “suggested” he come to Moscow—a move that neither Sorge nor the German Communist Party dared refuse.

Arriving in the Soviet capital in late 1924, Sorge was charged with setting up an intelligence network. In 1925, he joined the Soviet Communist Party and also became a Soviet citizen, a fact that was never reported to German authorities. He therefore retained his German passport, which would be of great benefit to him in the future.

Immersing Himself in the World of Espionage

Life in Moscow was good for Sorge, but it was bad for his marriage. In addition to helping expand the Comintern Intelligence Division, he had time to write two books and to hone his skills in other languages, particularly English and Russian. On the dark side, his constant drinking and womanizing made life unbearable for Christiane, who finally left him in the fall of 1926. Returning to Germany, she eventually emigrated to the United States.

With Christiane gone, Sorge immersed himself in the world of espionage. It became his passion, but he realized that the one true weapon needed for success in the game was absolute secrecy. By 1929, he felt that he was becoming too conspicuous for his own good. After meeting with his superiors, he was given approval to sever his ties with the Comintern and with any of the communist cells that he knew. Only a few chosen men were privy to the reason for the break.

Sorge’s next step was to join the Secret Department of the Soviet Communist Party Central Executive Committee. His superiors then arranged an introduction to the head of the Fourth Department (Red Army Intelligence), General I.A. Berzin. Seeing Sorge’s potential, Berzin discussed possible assignments with him, and after narrowing his choices, Sorge decided that China would be the ideal spot for him to ply his trade. Berzin heartily agreed.

Throughout the fall and winter of 1929, Sorge prepared for his mission with the utmost concentration. A crucial aspect of the operation was his cover story. Since he was still a citizen of Germany as far as German officials were concerned, he traveled to Berlin and got a job as a writer for the Soziologesche Magazin. His next stop was Marseilles, where he boarded a ship for a trip halfway around the world. The long voyage finally ended when the ship docked in January 1930. Sorge was now in Shanghai, where he would start to organize a spy ring in the city for the Red Army.

Help From the Japanese

One of the first people that Sorge met upon his arrival was a fellow member of the Fourth Department, radio technician Max Clausen. After thoroughly questioning Clausen, the “journalist” from Berlin decided that his radio expertise would serve the operation well. Clausen work for Sorge for most of his career.

For almost two years, Sorge built his intelligence network. He moved easily in the upper social circles of the city, and soon became a favorite at parties and other gatherings. At consulate affairs, he was able to rub shoulders with German advisers to Chiang Kai-shek, gleaning information concerning Chinese military matters.

In the latter part of 1930, Sorge was introduced to a pro-communist Japanese journalist, Hatzumi Ozaki. During his time in China, Sorge had become convinced that Japan held the key to the Asian continent. The amiable Ozaki gave him a chance to more fully understand not only Japanese culture, but also the Japanese psyche. The two men quickly became friends, drinking and womanizing together in some of the best and worst clubs in the city. With his pro-communist leanings, Ozaki was easily recruited and soon became one of the top agents in the Sorge spy network.

The Far East of the early 1930s was a seething cauldron filled with warlords, revolution, corruption, and armed conflict. Through his long conversations with Ozaki, Sorge was able to send Moscow Intelligence analysis reports of matters such as Japanese expansion in the area and policies that directly affected the Soviet Union. Besides teaching Sorge the intricacies of Japanese thought and politics, Ozaki was also able to recruit two other Japanese who would prove vital to Sorge’s intelligence apparatus—Shigeru Mizuno and Teikichi Kawai.

The two Japanese agents kept Sorge informed on Imperial Japanese Army movements on the Asian mainland. Japan’s military activities in Manchuria and Northern China were causing concern in Moscow, and Sorge’s reports kept the Red Army apprised of the constantly changing situation. Ozaki was recalled to Tokyo in January 1932, but Kawai, Mizuno, and other agents in the espionage network kept feeding Sorge a steady stream of information, which he passed on to Moscow.

Playing the Journalist in Berlin

Satisfied that Sorge had been successful in organizing the Shanghai network, Berzin ordered him back to Moscow in December 1932. Sorge had expected an assignment in the Soviet capital, but Berzin told him that he was once again needed abroad. After several meetings with the general and other members of the Fourth Department and the Central Committee, it was decided that Tokyo would be his next duty assignment.

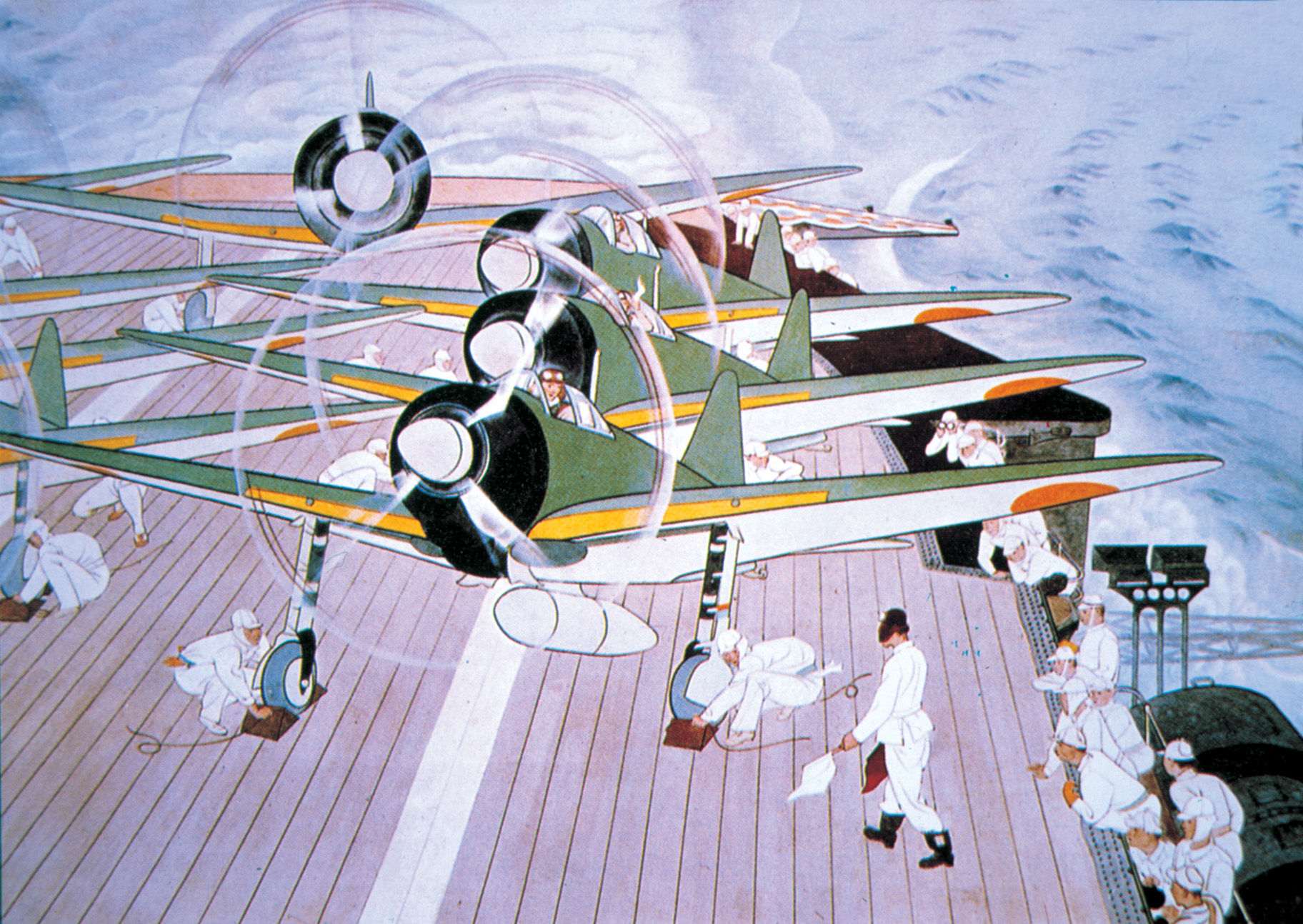

Sorge was to repeat his Shanghai performance by building up an espionage network inside Japan. Japanese nationalism was on the rise, and the Imperial Army and Navy, which had defeated China in 1895 and Russia in 1905, were ever looking to expand the country’s eastern frontier. Japan had already taken a huge slice of Northern China and Manchuria when Sorge received his assignment, and the Red Army was being forced to reinforce what was now a de facto Soviet-Japanese border.

To establish a cover, Sorge once again became a journalist, traveling to Berlin to establish his credentials. He landed a job with the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (Journal of Geopolitics), published by Kurt Vowinckel, an ardent Nazi, who had read some of Sorge’s articles from his China days. Vowinckel gave Sorge letters of introduction both to the German Embassy and to personnel on the embassy staff in Tokyo.

Sorge also met with Dr. Karl Haushofer, co-founder of the magazine, who was a personal friend of Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess. Haushofer gave Sorge letters of introduction to the German ambassador to Japan—letters that carried some weight because of his relationship in the upper circles of the Nazi Party. To cap off his extraordinary run of luck, Sorge also received a letter of introduction from the editor of the newspaper Täglische Rundschau. As an afterthought, the editor, a Dr. Zeller, also gave him a letter of introduction to Colonel Eugen Ott, a German Army representative in Japan. Zeller asked Ott to “trust Sorge in everything; that is, politically, personally and otherwise.” That letter was doubly important because in 1934 Ott became the German military attaché to Japan. As a final masterful gesture, Sorge applied for membership in the Nazi Party, receiving his membership card after he arrived in Japan.

Armed with impeccable recommendations, Sorge traveled to Japan via the United States where, after showing the Japanese ambassador Haushofer’s letter, he received another letter of introduction from the ambassador to the head of the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s Information Department. He arrived in Tokyo in September 1933 and immediately started using his stack of introductions to make himself known, both at the German Embassy and at the Japanese Foreign Ministry. His wit and charm soon won him many friends, and invitations to various functions soon followed. Keeping his cover, he also wrote features about Japan for his German newspapers.

Beginning The Mission That Would Last His Career

Sorge was a busy man in 1934, both as a “loyal” German journalist and as a Soviet spy. He rekindled his relationship with Ozaki, recruiting him for his new mission, and Kawai and Mizuno were also brought into the fold. Another recruit was Yotaku Miyagi, an Okinawan who had lived in the United States for several years before being ordered to Japan by the Communist Party.

In his role as a journalist, Sorge accompanied Ott to Manchuria in mid-1934 to visit Japanese forces stationed there. An avid reader, Sorge had been devouring every book about Japan that he could find, especially those in the original Japanese. That, along with his long discussions with Ozaki, made him one of the most knowledgeable members of the German community in Tokyo when it came to understanding their host country.

Returning from Manchuria, Sorge wrote an essay describing his thoughts about the trip and about what he had seen. He gave it to Ott, who forwarded it to the General Staff Economics Department in Berlin. The head of the department, General Georg Thomas, was impressed, and he requested Sorge to help prepare other reports in the future.

By mid-1935, Sorge had been in Japan for almost two years, and he had spent that time setting up a network of agents that had access to many important Japanese military and industrial departments. In May, Moscow ordered him home to report personally on his progress. His route to Moscow first took him to the United States, where he obtained a false passport from a communist agent in New York. Arriving in Moscow under an assumed name, he met General Semion Uritskii, who had succeeded Berzin as head of the Fourth Department.

During the meeting, Uritskii gave Richard Sorge a mission that would consume the rest of his career. Basically, Sorge was to keep Moscow informed about Japan’s political and military intentions regarding the Soviet Union; Japan’s intentions concerning the United States, Great Britain, and China; developments in the relationship between Germany and Japan; and the state of Japan’s heavy industries. Before Sorge left, he requested that the radio wizard Clausen be assigned to Tokyo. Clausen arrived in December, completing Sorge’s inner circle in Japan.

The Espionage Ring’s First Coup

The espionage ring’s first coup came in early 1936, when a group of young Japanese officers attempted a revolt. The rebellion was quickly crushed, and Sorge, using his sources within the government and the military, sent an analysis of the situation which was very well received by the Fourth Department. His report was soon followed by another one that dealt with a possible German-Japanese military alliance. Sorge kept Moscow updated on the talks and was actually involved in some of the discussions, thanks to his good friend Ott. His firsthand account of these discussions gave the Red Army a thorough and accurate picture of what was taking place.

The Sorge network continued to file reports through the first half of 1937. Then, on July 7, an ominous event took place at the Marco Polo Bridge in China. Japanese and Chinese troops had fired at one another during a Japanese training exercise. The so-called “China Incident” soon turned into a full-scale conflict between the two countries, and the entire Sorge network was now involved with gathering information concerning its military and political consequences. Sorge’s analysis of both opponents’ capabilities and intentions became an important component in forming Soviet strategy in the Far East. Conversely, in his role as the loyal German, he was also invited to take part in German Embassy discussions on how to mediate the conflict.

On April 28,1938, Eugen Ott was appointed ambassador to Japan, virtually assuring that Sorge would be privy to the highest diplomatic channels. Another stroke of good fortune occurred that summer when Ozaki was appointed to the Japanese government as a cabinet consultant. Both appointments allowed Sorge to send Moscow a continuous flow of information and observations that would become priceless as the world drifted toward war.

The Imperial Japanese Army struck Soviet forces at Khalkin Gol in Mongolia on May 11, 1939. Sorge immediately sent operatives to various ports and kept the Fourth Department informed on troop strengths and movements. He also sent a message stating that he did not believe Japan’s intentions were to initiate a full-scale war with the Soviet Union. His analysis of Japanese intentions was met with disbelief in the top echelons of the Red Army.

A Soviet counterattack led by General Georgi Zhukov devastated the Japanese forces in August and September. The Japanese agreed to a cease-fire on September 15, and Sorge used the Soviet victory to try to persuade Ott and other embassy officials that the Red Army was sorely underestimated by many countries, including Germany. That opinion was also met with disbelief and disdain.

The defeat at Khalkin Gol and the outbreak of the war in Europe put Japan on a heightened security level. Foreigners, even friendly ones, were now being shadowed by members of the Tokko (the Special High Police Bureau), and Sorge was no exception. The man assigned to trail and investigate the German journalist was 28-year-old Harutsugu Saito.

Problems In the Organization

Saito took his assignment seriously, keeping track of Sorge’s acquaintances, making friends with his housekeeper, and following the German to bars and other hot spots of the Tokyo night scene. Although Sorge was extremely careful when it came to his spy network, the intrepid Japanese policeman began to form a composite of his habits and preferences, noting anything that might be out of character.

Meanwhile, the Sorge organization continued gathering intelligence, keeping Moscow advised on issues such as German-Japanese naval discussions and a Japanese attempt to install a puppet regime in China. His “handlers” were so impressed with the data being sent from Tokyo that they extended Sorge’s tour another year.

In March 1940, Sorge informed the Fourth Department that Germany would launch an attack on Western Europe within weeks. His close ties with Ott and other embassy officials were paying off handsomely. He also received information concerning the Triparite Pact between Germany, Japan, and Italy, which he forwarded to the Fourth Department.

Nineteen forty was a very good year for Sorge, but his organization was beginning to unravel around him. In November 1939, the Tokko arrested Ritsu Ito, one of Ozaki’s assistants. He was held and interrogated for almost a year before being released in a new role as a police informant. There was also a problem with Clausen, the radio operator who played a key role in transmitting Sorge’s messages to Moscow. He was in the process of redefining himself as a “good German.” He had begun to doubt the tenets of communism and was becoming apprehensive about his work as a spy. Clausen also became resentful of the way the arrogant Sorge was treating him—talking to him as a lord to a serf instead of as an equal.

In the spring of 1941, the relationship between the Soviet Union and Germany began to crumble. German-occupied Poland was bursting at the seams with new Wehrmacht divisions, and in April 1941, Adolf Hitler unleashed units stationed in Bulgaria against Greece and Yugoslavia, which were conquered within a month. There was little doubt in Sorge’s mind that the next victim of Nazi aggression would be the Soviet Union.

Ignoring Warnings of a Wehrmacht Attack

Following the successful German invasion of the Balkans, Sorge began sending a stream of messages to Moscow, backing his belief that Hitler would soon attack. His suspicions were confirmed by several sources, including military couriers and the German military attaché in Japan, Colonel Alfred Kretschmer. In May, Sorge had Clausen send a message that detailed when the attack would come and how many enemy divisions would be involved. The message was ignored.

One reason for Moscow’s indifference could have been that, since early 1941, Clausen had been modifying Sorge’s reports. Sometimes he would delete entire passages, and other times he would deliberately make the entire report rather vague. In any event, the warnings went unheeded. On June 22, the Wehrmacht struck.

With Soviet armies reeling back all along the front, Sorge and company kept a watchful eye for any signs of a Japanese attack in Manchuria. Indeed, Japan was mobilizing, but there was a difference of opinion between the government and the military as to where the strike would take place—in the north against the Soviet Union, or in the south against Indochina and the islands of the Pacific.

Sorge’s agents were also divided. Ozaki reported that a southern strike was definite, but that it was still possible for a secondary strike to be carried out against the Soviet Union. Miyagi was also certain that Japan would expand in the south but noted that the Imperial Army was also building up its forces in Manchuria. Then, in late August, Ozaki learned that the army leadership had decided not to fight the Soviets. He went to Manchuria for two weeks in September and came back with confirmation that the army had no plans for a northern attack.

Armed with Ozaki’s information, Sorge ordered Clausen to send several messages to Moscow affirming that the Far East border was in no danger, at least for the remainder of 1941. The information and sources quoted in the messages left little room to doubt the validity of Sorge’s report. Coupled with the fact that Sorge had been right about the June attack, Stalin felt secure enough to delve into his pool of divisions in eastern Siberia. This decision altered the course of the war on the Eastern Front and probably saved the Soviet capital.

Pointing the Finger Directly At Sorge

In mid-October, units of German Panzergruppe 4 clashed with the 32nd Siberian Rifle Division, which had been recently stationed at Vladivostock. By November, Siberian divisions were being encountered all along the front protecting Moscow. It was Sorge’s greatest triumph, but it was also his last.

The Tokko had been relentless in tracking suspected communists since the clash at Khalkin Gol. On September 28, one of Miyagi’s recruits, Tomo Kitabayashi, was arrested. During her interrogation, she admitted that Miyagi had been involved in espionage activities. Miyagi was arrested on October 11. After an unsuccessful suicide attempt, he shocked his interrogators by revealing the work he had done, implicating Ozaki and Sorge in the process. The sheer magnitude of the operation astounded and shocked senior Tokko officials as they read reports of the interrogation.

On October 15, Tokko detectives picked up Ozaki, followed by the October 17 arrest of Mizuno. Both men spoke openly about their actions, confirming Miyagi’s story and pointing the finger directly at Sorge, who was still under the watchful eye of detective Saito. The morning following Mizuno’s arrest, the Tokko swooped down on Clausen’s home, taking him into custody along with a radio set and dispatches that had already been sent to Moscow. Now it was time to net the master.

Saito and two other detectives entered Sorge’s residence and arrested him without incident. At first, the spymaster protested his innocence. He was a close friend of the German ambassador and a well-known member of the Nazi Party. He had friends in high places, both in Japan and in Germany, and was a respected journalist. Sorge kept his denials flowing for six days until he was confronted with the confessions of the others, including Clausen and the recently arrested Kawai. On October 25, Sorge confessed to being a member of the Communist Party, and a spy.

A Later Hero to the Red Army

While the Japanese continued to investigate the scope of the spy ring, Sorge was allowed to work on his memoirs. His ever-present ego shone through as he recounted his various assignments and his thoughts regarding Germany, Japan, and the war. His case was finally tried in 1943, with Ozaki as a codefendant. On September 11, Ozaki was sentenced to death. Sorge received the same sentence on September 29.

Both men appealed their convictions, and both appeals were denied. On November 7, 1944, the two were executed by hanging. Sorge, ever defiant, shouted praise for the Red Army, the International Communist Party, and the Soviet Communist Party as the trapdoor opened and his body fell. It took him 19 minutes to die. Ironically, it was 27 years to the day that the Bolshevists had taken control of Russia.

As for the others, Miyagi and Mizuno died in prison. Kawai survived internment, and Clausen was liberated from prison by the U.S. Army. He was flown from Japan to the Soviet Union and then made his way to East Germany, where he once again became a dedicated communist.

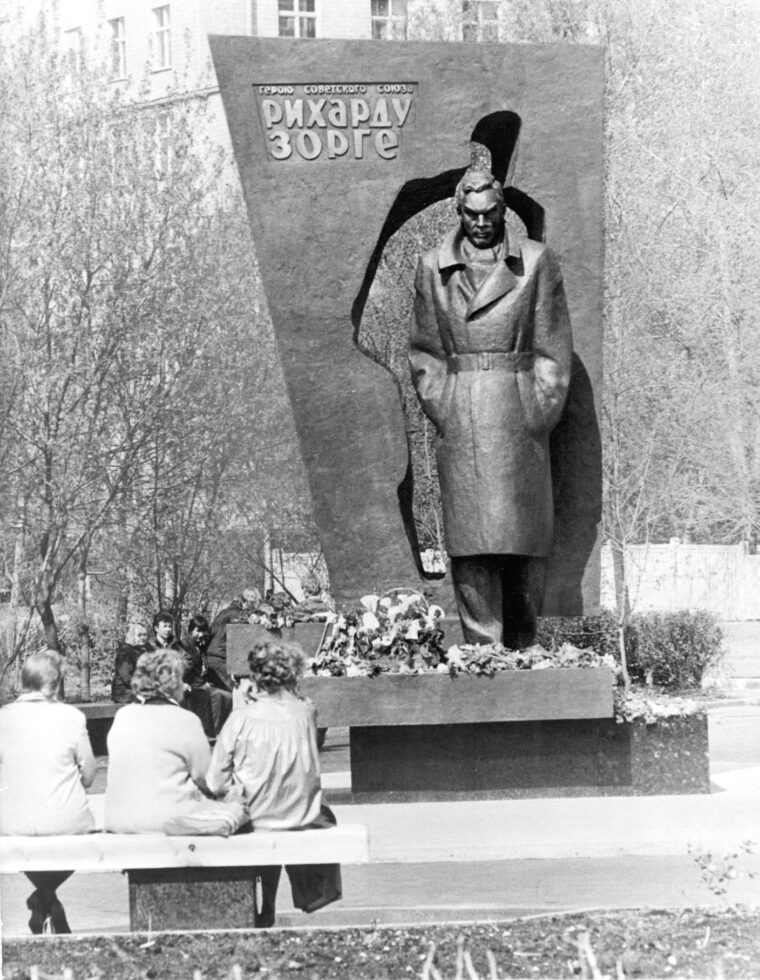

Ironically, although Sorge’s exploits were well known in the West, the Soviets kept a veil of silence surrounding the spymaster until long after Stalin was dead. It was only on November 6, 1964, that Moscow publicly recognized his contributions, proclaiming Sorge a Hero of the Soviet Union.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments