By Robert Barr Smith

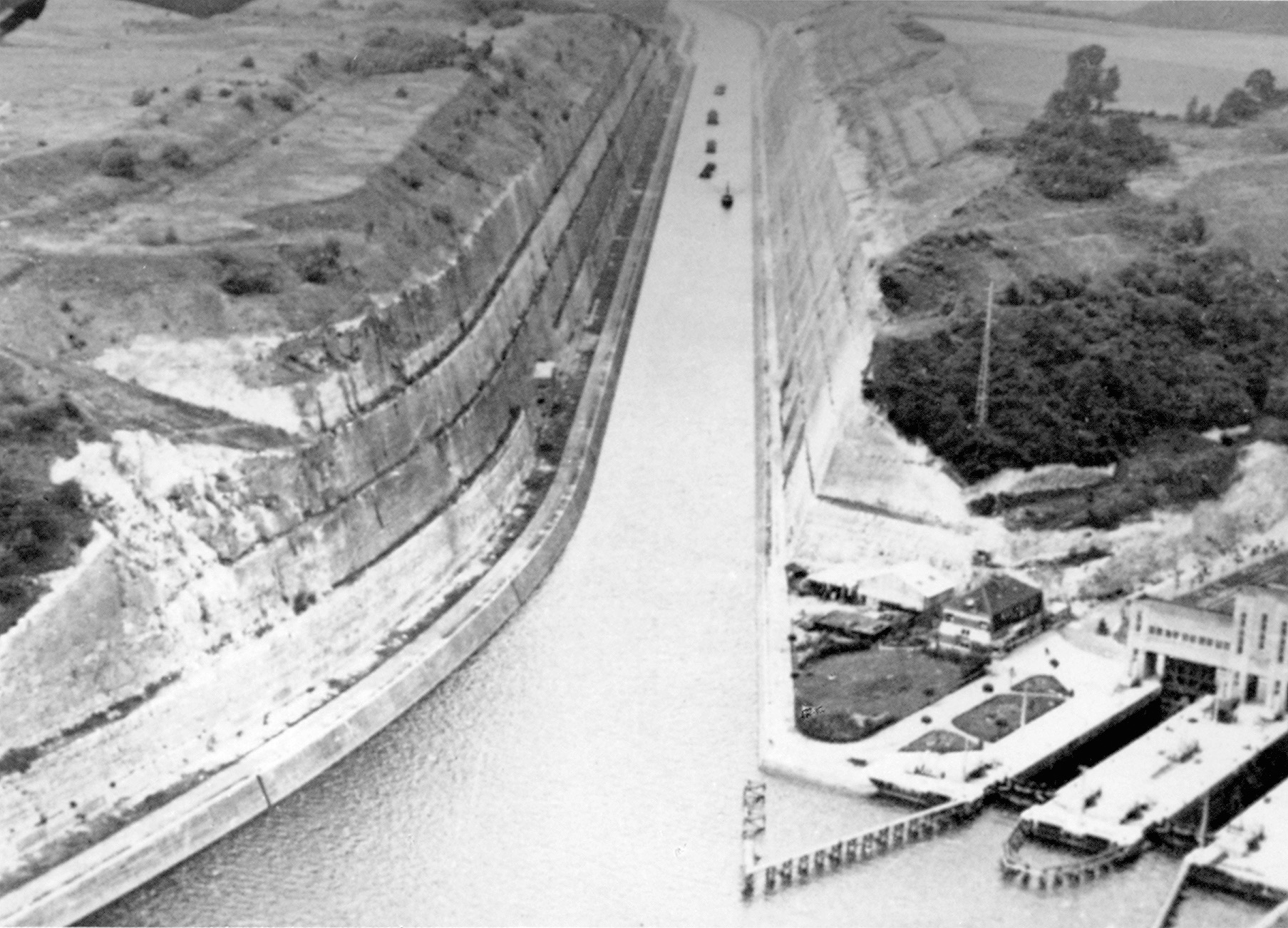

Belgian Fort Eben Emael was as close to impregnable as modern defense works could be—or so it seemed. The installation was new, for one thing, just completed in 1935. It was the highest refinement of contemporary military architecture, one of a half-circle of eight forts covering the vital Belgian city of Liège. Now, in May 1940, it commanded the vital Albert Canal bridges at Vroenhoven, Canne, and Veldwezelt, the most direct pathway to the west for Adolf Hitler’s mechanized juggernaut.

The bridges were all garrisoned and wired for demolition, and each was overlooked by a concrete bunker whose crew controlled the demolition—they would blow the bridges on order, or on their own initiative in case of emergency. If the Belgians blasted the bridges into the river, the guns of Eben Emael would fire on any attempt by German pionieren (combat engineers) to throw bridges across them. If the demolition charges failed for any reason, or their firing parties were overrun, the fortress’s guns could shell the bridges into junk.

In the autumn of 1939, Hitler urgently summoned General Kurt Student to Berlin. Student, a World War I fighter pilot, had transferred to the infantry after the war but retained his interest in aviation; he was an enthusiastic glider pilot. He was now commander of 7th Flieger, Germany’s sole airborne division. Since the Polish campaign, the Luftwaffe had controlled paratroops in the German system, and Student had accordingly moved from the army to the air force.

Hitler had work for Student. “Do you know Eben Emael?” he asked. “Of course,” said Student. There had been much written about the place, and indeed, the Germans had access to many details about the fortress since two German contractors had been involved in its construction. “I have an idea,” said der Führer. “I know you are a glider pilot. Can you land an assault force by glider on the grassy top of the fortress and attack its defenses?” Student asked for time to think the problem through, but returned the following day to tell Hitler that he thought it could be done.

Hitler then launched into a discussion of the capture of French Fort Douaumont in World War I. Douaumont, part of the Verdun defenses, had fought well until it was battered into ruin by heavy German artillery. Hitler, it appeared, had drawn a lesson from its fall. “We have a new weapon that will destroy Eben Emael,” he said. It was the hohlladung, the hollow charge, which would concentrate the explosive force of the charge into a jet of molten metal that would slash through concrete or steel. It came in both 20-pound and 110-pound sizes, and it had to be placed on the target by hand. The larger charge came in two parts, for easier carrying.

Germany’s Flying Laboratories

Between the world wars, Germany, deprived of an air force and most other heavy armaments, turned to ingenuity and subterfuge to train her new armed forces. A new generation of pilots learned their trade in unpowered gliders, which were not prohibited by the Versailles Treaty. Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring, as early as 1922, revealed the future: “[W]e will teach gliding as a sport to all our young men. Then we will build up commercial aviation. Finally, we will create the skeleton of a military air force. When the time comes.…”

Many pilots were trained in the National Socialistische Flieger Korps, an arm of the Hitler Youth. Prior to the outbreak of World War II, many of the world’s foremost sail-plane pilots were German.

And Germany also turned her attention to the construction of gliders larger than the average sport sail-plane. One was a flying laboratory, and when Luftwaffe General Ernst Udet saw that aircraft, he began planning for a combat version, an inexpensive glider that would carry at least nine combat-loaded infantrymen. The result was a sturdy troop-carrying glider called the DFS 230. It could be towed into action by Tante Ju—Aunt Ju—the reliable tri-motored Junkers 52 transport. The aircraft was test-flown by Hanna Reitsch, a champion sail-plane competitor and test pilot, who suggested changes. It was also improved with a new brake, shaped rather like a plow, to stop the glider more quickly on landing.

The DFS 230 was designed to carry about a ton and a half of cargo, more than its own weight. Its great value was that it could deposit a fighting unit together, ready to go into action, rather than scattered across the landscape like a stick of paratroops. Hitler had clearly seen it as the ideal weapon to strike the mighty Belgian fortress at its only weak point, and Student went immediately to work to choose and train his strike force.

Sturmabteilung Team Prepares to Strike Eban Emael

He chose well. The attackers would be commanded by Captain S.A. Walter Koch, a paratroop officer drawn, like the other members of the force, from Student’s own airborne division. Koch’s force was composed of volunteers, 11 officers, and 427 enlisted men. They would have three missions: neutralize the great fortress of Eben Emael; attack and take—intact—the three Albert Canal bridges at Veldwezelt, Canne, and Vroenhoven; and hang on to all four targets—at all costs—until German ground forces could get there.

The unit was dubbed Sturmabteilung (storm detachment) Koch, and its commander split it into four combat teams, each assigned a specific target. Leutnant Schact would lead 96 men—the assault group called Beton (concrete)—against the Meuse bridge at Vroenhoven. A detachment of 92 paratroopers, called Stahl (steel), was to follow Oberleutnant Altman against the Veldwezelt bridge.

Leutnant Martin Schaechter commanded Eisen (iron), 92 men assigned to capture the span at Canne. The strike on Eben Emael itself would be led by a tough, able Oberleutnant named Rudolf Witzig. Witzig was 23 years old, an engineer and professional soldier. He would lead a force of pionieren: two officers, 73 enlisted men, and 11 glider pilots—only these few, code-named Granit (granite), against the mighty fortress.

Inside Germany, near Hildesheim northwest of the Harz Mountains, the raiders practiced on fields laid out in the size and shape of Eben Emael. They were also given a section of Czech fortifications west of Prague—the one-time Benes Line—on which to practice assaults on gun cupolas and casemates. Captain Koch drove his men hard, and Witzig was as tough as his commander was. They rehearsed again and again on mockups in the Harz and Czechoslovakia, enduring endless drills in assaulting their objectives; getting out of their gliders at top speed; and stowing, securing, and unloading their weapons and gear, including the 110-pound shaped charges.

The strike force spent hours studying models of its targets, picture postcards of the area, and aerial photographs. The soldiers were briefed on fortress construction by teachers at the German Engineer School and studied statements from Belgian deserters and from German workers who had helped to build Eben Emael. The bridge-assault detachments rehearsed repeatedly on similar bridges inside Germany.

The glider pilots had their own rehearsals, endless practice in postage-stamp landings. The attack squads had to be put down as closely as possible to the particular casemates, bunkers, or cupolas assigned as their targets, and the glider pilots’ standard was to land within 20 meters of each objective. They had to get their fragile gliders on the ground as quickly as possible, exposing them and their human loads as briefly as possible to ground fire. Koch’s unit rehearsed glider assaults on the one-time Polish border fortifications at Gleiwitz.

The Eben Emael landing would go in with the first dim light of morning—Student had insisted on that—so the pilots would have a reasonable chance to see and hit their targets. Even so, the pilots had to be perfect. They would have just one chance to do it right, and a lot of lives depended on their skill. After the gliders were on the ground, the pilots would fight as infantry.

Shrouded in Utmost Secrecy

The operation was shrouded in the utmost secrecy. Nobody sent mail or made telephone calls, and the force concealed its identity behind a series of false and unenlightening unit names. Airfield Construction Unit, one of the aliases of Witzig’s command, was hardly a title to alert anybody to the real purpose of the unit.

Witzig’s men were loaded with ordnance in addition to their own infantry weapons and hand grenades. They carried small explosive charges designed to push into viewports and cannon muzzles. There were charges on poles to shove into firing embrasures, flamethrowers, and Bangalore torpedoes to cut paths through barbed wire. Witzig requested, and got, special small charges to stuff into the view- ports of the all-important observation cupolas, the steel eyes of the fort’s artillery. He knew that if he could take out these observation posts—or blind them by destroying their periscopes—the big guns of the fortress would be useless.

Then there was the hohlladung, the new weapon based on the “Monroe Effect,” named for its American discoverer. This murderous device was nothing more complex than a hemisphere of explosive with a dish-like section scooped out of its bottom. The scooped-out section, the large end of which pointed at the target, was lined with metal. When the device fired, the shape of its structure directed an enormous shock-wave, liquifying the liner and spurting a slim jet of liquid metal like a knife into steel or concrete. Witzig’s paratroopers trained with the heavy charge, the men running while carrying half of the bomb in each hand with leather carrying straps. They would take along 25 of the large charges and 25 more of the smaller ones.

Oddly, Witzig never permitted use of the hohlladung against steel or concrete in training, although he had plenty of now-useless Czech fortifications to blow apart. It was better, he thought, that his men did not know the awful power of the thing with which they practiced. If they knew the capability of the charge, that fact might prove so astonishing that the secret would leak out, compromising the mission.

In February 1940, Granit’s 11 glider teams staged a full-scale attack on their section of the Benes Line, using all their weapons except the hollow charge. Witzig permitted these to be fired only into the bare earth, where they left an uninformative and somewhat unsatisfactory crater in the dirt. By the time the Benes Line exercise was completed, the strike force knew everything about its mission and its target, except where it was and what it was called.

The gliders that would carry Sturmabteilung Koch moved from Hildesheim in sealed furniture vans and were hauled to Ostheim and Butzweilerhof airfields near Cologne. Delivered in pieces, the DFS 230s were assembled at night, shrouded by clouds of vapor from smoke generators, behind guarded fences covered with matting to frustrate the gaze of the curious. As the aircraft were completed, they were hidden away in newly built hangars. In five days, the gliders were safely under cover. The Luftwaffe mechanics who had put them together were held incommunicado just as were the men of the strike force. Training of the strike force continued.

Witzig’s Brush With Death

On May 1, 1940, the unit was alerted and the tension grew until, on the night of May 9, word filtered down to the troops that the operation was on at last. In late evening the airfield lights were extinguished, field kitchens appeared to feed the troops, and the Junkers 52 tow planes began to descend to the airfields. Once they were parked, ground crews pushed the gliders out onto the strip, marrying up each with its tow plane. The weaponry was loaded, and every foot of the tow ropes was inspected by flashlight. For the soldiers, there was nothing to do now but wait, play cards, doze, and talk. A little before midnight, Witzig tersely told his men they were to attack “a fort” in the Belgian defense system.

At last, around 0300, officers and NCOs ordered the men of Granit to load up. One by one the tri-motored Junkers labored off down the strip and lumbered into the black sky, the gliders following reluctantly. The armada climbed through the gloom, reaching for its target altitude of 8,500 feet above blacked-out Germany. Each Junkers had a series of small lights set beneath its tail, invisible to anybody but the pilot of the glider behind. The lead aircraft followed a series of beacons set up by Luftwaffe units leading toward their objective. They flew on into the night without incident until near-fatal calamity robbed the unit of its leader.

Witzig’s own glider, flown by a Corporal Pilz, suddenly went into a violent dive. Pilz was expertly following the evasive action of his tow plane, which swerved to avoid another aircraft close above it. Both craft avoided the stranger, but the violent evasive action broke the tow line, and Pilz—knowing he could not make Eben Emael—had to put the glider down in a field of weeds. Witzig, furious, told his men to knock down fences and clear a rough runway, rousted out an officer from a nearby German unit, got a car, and roared back to Ostheim airfield. Yes, he was told, he would get another Junkers to retrieve his glider and his men.

Time was running out, and up ahead in the blackness Granit lost another glider when the Junkers towing it signaled the glider pilot to cast off the tow. The pilot, a Corporal Bredenbeck, knew the signal was premature but had to cut loose when the tow plane turned and began to dive. Bredenbeck had some 25 miles still to go, without enough altitude to reach the fortress. The attack force was now down to 70 men.

“Airplanes Are Overhead! Their Engines Have Stopped!”

Just after 0400 the aircraft caught sight of their last beacon, a light on a hilltop northwest of Aachen. Although the attack plan called for the gliders to drop their tows at this point, the signal did not come. The tows and their gliders were too low and too early, and so the formation droned on for another 10 minutes until it reached the planned release altitude of 8,500 feet. Now the signal came, and the gliders cut loose from the mother planes, alone in the night, watching Dutch antiaircraft around Maastricht firing into the blackness.

Across the line of the Meuse and the Albert Canal, the Belgians were already alert. Reports began to come in from the Canne bridge and an outpost near it that many aircraft were approaching. Major Jean Jottrand, commanding at Eben Emael, had already sent details to clear out and set fire to his above-ground barracks, clearing fields of fire for the defenders. Now he puzzled over the reports, especially one that somewhat obscurely stated: “Airplanes are overhead! Their engines have stopped! They stand almost motionless in the air!” Without experience or information, neither the major nor anybody else could guess that the uninformative report meant the enemy was approaching in gliders.

Jottrand heard the hammer of gunfire below him along the canal, as one Belgian unit after another opened up on the dark, silent birds swooping soundlessly down on them like malignant bats. And now Jottrand and his men could see them too, but Eben Emael’s antiaircraft emplacements were silent. Frantic calls came from headquarters: “Why aren’t you firing?” The officer in charge of the guns said he did not know who the silent aircraft belonged to, but they weren’t Belgian. “Well then, shoot!” roared headquarters, “Goddamn it, shoot!”

The command came too late, for the gliders were already landing, and there was trouble at the canal bridges as well. Jottrand had ordered the Canne bridge blown once he saw aircraft descending on Eben Emael, but nothing happened. He had to give the order again before the Canne bridge was blown into the canal. Schaechter’s platoon had been just too late. At the Veldwezelt bridge, however, Altman’s men swarmed out of the gliders and took their objective intact. Altman blew the major defensive casemate with a hollow charge. By the end of the day, his platoon would lose eight men dead and 21 wounded, but he would hold on.

Oberleutnant Schacht’s platoon overran the defenders at the Vroenhoven bridge in one ferocious rush. Schacht lost seven killed and 18 wounded, but he had the bridge intact; his men pulled the demolition charges before they could be fired. Meanwhile, Koch’s headquarters group laid on radio contact with his scattered attack elements. Within three hours, all significant Belgian resistance around the bridges would be over.

So two bridges remained intact and ready to use, for no signal had come to fire the demolition charges. Here the Belgian failure was caused by Stuka dive-bombers of the Luftwaffe. For as the sector commander was alerted to the attacks on the bridges and reached for his telephone, four of the gull-winged aircraft screamed down on his headquarters. The commander and 20 others died in the ruins, and the critical signal was never sent.

The Germans now had two major routes open to the west. The Belgians’ only hope was the guns of Eben Emael. If they could come into action quickly, the spans might still be blown into junk before the German armor could cross to the west.

Granit’s gliders, however, were already landing on the grassy top of the fortress. Even without Witzig, the long months of training were paying dividends. Every part of the Belgian defensive system had raiders assigned to neutralize it, and Oberfeldwebel (Master Sergeant) Helmut Wenzel took control of the attackers. The assault squads sprinted through the dim light of dawn, grenading machine-gun emplacements, spraying viewports with small arms fire. As they identified the casemates and cupolas that were their targets, the raiders began to plant the hohlladungen and touch them off.

The effect was astonishing, the more so since none of the men on top of Eben Emael had ever seen what a hollow charge would do to armor or concrete. The squad led by a sergeant named Niedermeier laid a hollow charge against the entry to a cupola housing a pair of 75mm cannon and touched it off. The explosion killed four Belgians, wounded seven more, and burned another eight, leaving the inside of the turret a charnel house, its guns useless. Behind the blast, German paratroopers dropped into the turret, pouring bursts of small arms fire down the shaft. All the surviving Belgians could do was retreat behind steel doors and steel-beam barricades. They were safe for the moment, but they were completely out of the fight.

The same scene was repeated over and over again across Eben Emael. In another 75mm turret, the Hohlladung blast flattened the gun crew and blew a gun tube completely out of its mount and down a 60-foot access shaft. Inside, the Germans sprayed bullets down the shaft and finished the job with an explosive charge dropped down it. As the smoke cleared, there was no sound from below.

Blowing the Fortress

As assault teams methodically neutralized the fort’s observation posts and artillery cupolas, other paratroopers dug in, set up machine guns, and opened fire on Belgian infantry probing toward them. Belgian artillery was finding the range now, and the attackers were under heavy fire from a dilapidated building on the north end of the fortress. And it proved impossible to silence 75mm fire from Casemate No. 23. A heavy hollow charge rocked the turret and damaged the gun-laying mechanism, but it did not penetrate. The Belgian gun crew inside, with great courage, kept on shooting, even though they had to re-lay their cannon after each round. Heavy Belgian artillery and small arms fire drove the Germans under cover before they could set up another hollow charge. Along the way, Master Sergeant Wenzel was hit, but he came of tough stock. His head streaming blood, he stayed in command.

As German troops began to push across the canal, the Belgian officer commanding the 120mm guns waited for orders to fire on his pre-plotted primary target, the Vroenhoven bridge. At first, neither Jottrand nor the distant headquarters in Liège gave the word. At last, about 1030, the order finally came down, but the 120s got off only a single round. Wenzel stuffed a charge down the gun tubes, and the blast filled the air with fumes, driving the crew from the turret. By this time, much of the fortress was filling with fumes from the explosives. Some of the Belgian defenders were forced to put on gas masks. In spite of this, several casemates continued to fight on.

The attackers did not have it all their own way. Within a quarter-hour of landing, two Germans were dead and eight badly wounded, leaving just 62 men to hold down the garrison of the mighty fortress. Although the defenders had been driven into the bowels of Eben Emael, nobody knew when they might come popping out of some sally-port to sortie against the handful of paratroopers.

Heavy and accurate Belgian artillery fire was falling on top of Eben Emael, and there was no telling when Belgian infantry from the west might swarm over the fort in a counterattack. With Witzig missing, the only officer left with the attackers was a lieutenant named Delica, a Luftwaffe liaison officer who was cut off on the southern end of the fortress. Wenzel remained in command and called in Stukas to hammer those Belgian positions still holding out. Then, about 0830, into this maelstrom of fire flew a solitary glider. Oberleutnant Witzig had arrived.

Major Jottrand tried to mount counter-attacks from inside Eben Emael, but his efforts came to nothing. All of his men were garrison troops, gunners, and none had been trained to fight as infantry. When their commander called for volunteers, there were few hands raised, and the timid sortie that followed accomplished nothing. A second attempt to clear the top of the fortress involved a Belgian infantry detachment from a neighboring position, but these men knew nothing of the terrain on the fort’s top. This attempt collapsed under repeated attacks by the Stukas, as did a second sortie by the fortress garrison, ill-armed, short of grenades, and without machine guns.

In the early afternoon, a Belgian detachment at the village of Wonck, just three miles away, launched a counterattack. There were about 200 men involved to start, but the attack fell apart beneath the screaming Stukas. The remains of the force from Wonck, about a hundred, took refuge inside Eben Emael and could not be rallied to go outside the fortress again. It was the beginning of the end, even though a few of the defensive positions were still in action.

As night fell over the embattled fortress, Eben Emael’s garrison huddled below ground, shielded by their steel-beam barricades, sand-bag barriers, and steel doors. For the night they were safe, but the German paratroops still controlled the ground above them. Belgian artillery from Forts Pontisse and Barchon shelled Witzig and his men to discourage further attacks, but in fact, wrote Witzig afterward: “That night was uneventful. After the hard fighting during the day, the detachment lay, exhausted and parched, under scattered fire from Belgian artillery and infantry outside the fortification; every burst of fire might have signaled the beginning of the counter-attack we expected, and our nerves were tense. For the most part, however, the enemy lacked the will to fight.”

Across the Canal and Closing In

The Germans did not. In spite of the Belgian artillery, at 0200 a monstrous explosion rocked Eben Emael. The defenders thought it must be a salvo from German artillery, maybe heralding an infantry attack, so those Belgian positions remaining in operation opened up into the darkness. Fire ceased when no assault followed, but in the gloom German paratroopers stuffed 2-pound charges down the tubes of two of the remaining 75mm guns. That emplacement, too, fell silent. One other turret kept firing throughout the night, dropping shells among German units across the Meuse and harassing Witzig’s men on top of the fort. While this position’s gallant resistance was an annoyance, it could decide nothing, since the critical gun emplacements, those that could fire on the bridges, were permanently silent.

During the afternoon and night of the 10th, German troops of 51st Engineer Battalion made several attempts to cross the canal in assault boats, but each time were driven back by Belgian fire, especially from Eben Emael’s Casement No. 13. At last, late at night, the sappers got a party across the canal, linked up with Witzig’s men, and used demolition charges to finally silence No. 13. The fort’s garrison fell farther and farther back inside its tunnels, as the Germans dropped demolition charges and grenades into Belgian positions and sprayed small arms fire down the fort’s passageways. Now the Germans were beginning to send troops inside the fortress, grenading and tearing down the sandbag walls the Belgians had thrown up. The attackers were also working around to the west of the fortress, and German tank units were across the canal and closing in. German infantry had joined the paratroopers and the sappers on top of Eben Emael.

By 1000 on May 11, few of the fort’s guns were still in action. The corridors were littered with debris, crowded with wounded men. Barrels of chloride of lime, used for sanitation, had been ruptured by the explosions. Now chlorine gas was added to the smoke and fumes of the battle. In part of the fort, the air conditioning had failed, and the defenders were forced to wear gas masks. While many of the garrison fought gallantly on, others had simply given up. One officer was found hiding under a bed. Major Jottrand, still in communication with Liège, told his superiors flatly that without a counterattack, Eben Emael was lost. There won’t be any help, was the reply, and Jottrand knew his war was over.

No Surrender: Eben Emael Must Be Destroyed

Repeated telephone calls to higher command could not even produce an order to surrender—no more than an adjuration that only Jottrand could make that decision, coupled with an order to “blow up the works” after getting the garrison out. If that were not possible, said the message, “you are ordered to blow up the Fort and all its men.” This was all very well if the man giving the order was someplace else; the view from inside the dying fortress was quite different.

Jottrand was not having any part of a Götterdamerung. He called a council of war with his ranking NCO and such officers as were still on their feet. Every one of them declared in favor of surrender. Jottrand, still full of fight, tried to rally support among his men for an attempt to break out, but his soldiers would not move. At last, Jottrand called higher command, but he got the same answer: No surrender. Eben Emael must be destroyed.

So, Jottrand sent an officer to open surrender negotiations, while he saw to it that as much of the operative equipment as possible was rendered useless. About 1215 a bugle sounded from within the fortress, playing the same call again and again. It was the call for surrender. Before any real negotiations could take place, the Belgian garrison began to file out into the sunlight, hands raised. The German commander of the sapper battalion approached Jottrand. “Major,” he said, “will you give me your word that no delayed-action charges have been left behind?”

“I will,” said Jottrand. With that Eben Emael’s war was over. It had lasted about 30 hours.

Witzig took his exhausted men into the nearby village of Eben Emael and found a bar. It was time for a beer, or more than one, and the men of Granit took a few hours of well-deserved rest. Then they began their return trip to Germany by way of Maastricht and Aachen. Altogether, Koch’s little force had lost 37 dead and a hundred wounded. It was a small price for an astonishing success.

A handful of German paratroopers had captured the hinge of the Belgian defensive line south of Maastricht, at a cost of only six dead and 20 wounded. Of the garrison, 23 Belgians were dead and hundreds more were prisoners, 59 of them wounded. From that moment, Belgian national morale began to sag. With clear passage across the Meuse and the Albert Canal, Germany’s panzers raced on toward the west and the English Channel. It had been an extraordinary feat of arms.

Germany was jubilant at the fall of the fortress. The rest of Western Europe was shocked, especially since official German accounts, even newsreels, said nothing about either gliders or hollow charges, so that the world concluded the German success had been an ordinary ground attack. Some guessed that poison gas or sabotage might have been a factor. LIFE magazine published a fantastic story that German workers from the fort’s construction days had married Belgian women, become endive farmers, and under that cover had planted explosive charges beneath the fort.

Each man of Koch’s force received the Iron Cross (with one exception, a free spirit who loaded his canteen with booze); each officer was awarded the Ritterkreuz, the Knight’s Cross.

Koch After the War

Koch’s force broke up shortly after the attack on Eben Emael. Koch, now a major, rode another glider into the assault on Crete, which would prove to be the grave of much of the German airborne. Witzig was there too, and Wenzel, though this time these two went in by parachute. Witzig served later in Russia, and after the war rose to colonel in the peacetime German Army. Wenzel was commissioned, rose to the rank of captain, and became an American prisoner in North Africa. With the war’s end, he went home to become an Oberjaeger, master of a peaceful forest.

Major Koch did not survive the war. He was a lover of fast automobiles, and one night on the autobahn in 1942 the fates caught up with him. It is one of the ironies of war that this bold, hard-charging soldier should survive two of the war’s most spectacular actions to die crushed in his roadster beneath the rear of a truck.

The fortress is an empty shell today, a relic from another time. The Eben Emael Association gives two-hour guided tours to visitors, and there is a museum at the site. People of another generation can walk through the casemates and bunkers, now silent, and learn something of two desperate days in May, 61 years ago. If there are ghosts in the old corridors, they are quiet too.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments