By Paul Garson

During the 12 years of the highly militarized society of the Third Reich, some 20 million Germans—men and women as well as children—donned a uniform of one kind or another. Although Hitler was diametrically opposed to women serving in the military—and even in the heavy machine industries—the female members of the population, especially those residing in the cities, had already become an established part of the German work force after the horrendous losses during the First World War. That level of integration and participation rapidly increased during World War II as manpower shortages mounted due to battlefield attrition.

The Pivotal Role of German Women

Under control of the Nazi party, intellect was subsumed by an emphasis on emotion, a tie-in to the “blood and soil” precept that mandated that all Germans were one spiritual community and should act as such, rather than as individuals.

Females were seen as “the incubators of new German soldiers,” as housekeepers and child rearers. This mindset extended to a restriction on the number of females allowed to attend university, specifically concerning the areas of law and medicine. The Nazi state imposed a quota for females of 10 percent of the total university medical students, but eventually removed that restriction as the war increased the need for medical professionals. By 1944 one of eight doctors was a woman, while the number of nurses increased from 18 to 20 per 10,000 of population.

Italian journalist Filippo Bojano, who spent years living in Nazi Germany, commented on Hitler’s effect on women after attending an early campaign speech: “I could see the seething masses of women who were becoming ever more and more mesmerized by him as they listened to every word he uttered, and who kept up a prolonged orgy of cheering when he had finished.

“Strange to say, Hitler’s first supporters came from the masses of the female electorate. His first and most enthusiastic audiences were women, and I am firmly convinced that the German women will be the last to admit that Hitler’s political career has been disastrous to Germany.”

Hitler, however, was strongly opposed to women in the military—or even in industry for that matter, regarding them as the “incubators” for Germany’s future soldiers. As a result, motherhood was sacrosanct in Nazi Germany, with mothers ranked with the same status of frontline troops. A popular slogan was, “I have given a soldier to the Fuhrer.” In effect, these women were the breeding ground for the replenishment of the fallen warriors of the Fatherland.

In consideration of their contribution to the Nazi state, prolific childbearers were awarded special medals: the Honor Cross of the German Mother with Bronze for more than four children, Silver for more than six, and Gold for eight or more. Between December 1939, four months into the war, and May 1940—at the invasion of France—some 121,853 Honor Cross Gold medals were awarded during the annual Mothering Sunday, celebrated on the second Sunday of May (celebrated in many other countries as Mothers’ Day).

Adolph Hitler once wrote, “I want a brutal, domineering, fearless, cruel youth. Youth must be all that. It must bear pain. There must be nothing weak and gentle about it. The free, splendid beast of prey must once again flash from its eyes. That is how I will eradicate thousands of years of human domestication. That is how I will create the New Order.”

Breeding for the New Order

Germany needed to accelerate the production of military personnel, just as its assembly lines were turning out greater numbers of guns and tanks and warplanes; Nazi programs sought to remove the stigma of children born out of wedlock and, in fact, encouraged it with financial stipends and state care facilities.

SS men—the elite of the elite—were particularly encouraged to take part in the so-called Lebensborn (“Fount of Life”) repopulation efforts, in which females were gathered at facilities specifically established to encourage the propagation of der Übermensch (“the Overman;” a superior people).

Nazi Germany’s social engineers sought the most exceptional women to serve as breeders, particularly those trained and graduated as Hohen Frauen (“High Women”) from the Glaube und Schönheit (“Faith and Beauty”) program.

Its organizers sought out the most attractive girls of the highest intelligence, especially those who were instructed in gymnastics, horseback riding, pistol shooting, fencing, and automobile driving. The concept was formulated by no less than the Third Reich’s chief architect, Albert Speer, in collaboration with Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach and famous filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl—three of the Third Reich’s “beautiful people.”

Youth for Hitler

The term “Hitler Youth” (Hitler Jugend) came into effect in July 1926, when German youth groups were placed under the control of the SA (Sturmabteilung, or “Storm Division”) and divided into several Obergebiete, or geographic areas: Nord, Süd, Ost, West, Mitte, and Südost (North, South, East, West, Middle, and Southeast).

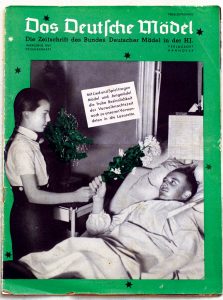

The female section of the Hitler Youth was called the Bund Deutscher Madchen (BdM), or League of German Girls. By 1936, the Hitler Youth had 5.4 million members aged 10-18. Almost all pre-Third Reich youth groups, both boys and girls, were assimilated into the Nazi collective organizations.

Some groups, particularly the religiously affiliated, balked, but all eventually fell under the thrall of the Nazi state, to whom control and conditioning of Germany’s children was a top priority. The state would now supplant the traditional family as the controlling force in rearing the nation’s youth.

While German females were deemed “wombs for the Third Reich,” any sense of sexuality was downplayed. Conservative clothing and hairstyles were de rigueur, and the wearing of pants, lipstick, make-up, high heels, and silk stockings—as well as smoking—were all frowned upon to the point of penalty.

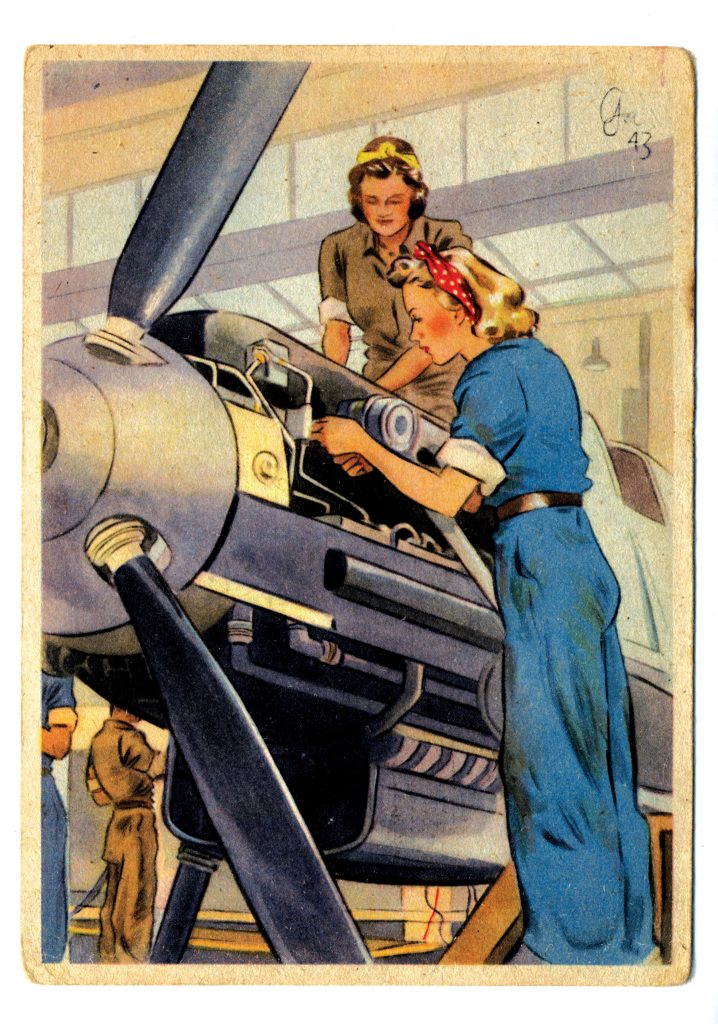

Working with one’s hands was considered mandatory for true German girls and evidence that she understood the “blood and soil” philosophy of the Nazi Party. Hundreds of thousands of young girls toiled on farms or provided household aid, often 13 hours a day, six days a week, as part of the mandatory RAD (Reichsarbeitsdienst) youth labor service.

They were also charged with collecting medicinal herbs and teas (some 6.5 million hours were invested by a million BdM girls in that endeavor). Later, they found themselves laboring in war-industry factories, often under Allied bombing.

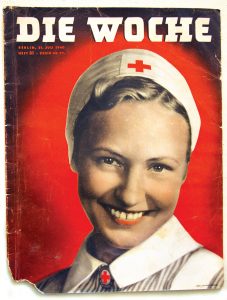

German Red Cross

Red Cross worker on the cover of one of its issues.

The Deutsches Rotes Kreuz (DRK) comprised both nursing and career-administrative personnel. In addition to its civilian volunteer work, the German Red Cross supplied the nursing staffs to all branches of the Wehrmacht.

Extensive recruitment efforts called for women of 16-21 years to come to the aid of the country’s soldiers by serving as nursing auxiliaries (Schwesternhelferin), the training beginning with rudimentary first aid via the BdM. All DRK personnel, including its nurses, swore an oath of allegiance to Hitler.

The DRK provided nurses for all branches of the German military, from city hospitals to frontline field units, who often found themselves in harm’s way. Red Cross female volunteers were not all necessarily certified medical nurses, and many dispensed food and water, aided regular medical staff, helped during bombing raids, and gave what medical assistance they could.

DRK nurses were often in the thick of battle serving in field hospitals behind the front lines. Several were awarded commendations for their valor in attending the wounded under fire, including Elfriede Wunk, the second woman after test pilot Hanna Reitsch to earn the Iron Cross.

She also was wounded several times.

Another recipient was Countess Nina von Stauffenberg, a volunteer nurse and also a pilot. Her husband, Claus, would later find his place in history as the staff officer who placed the bomb in Hitler’s command post in the abortive assassination plot. He was executed by the authorities, and she was arrested and sent to prison; their five children were placed in an orphanage.

A large percentage of German Red Cross-affiliated nurses and hospital personal were affiliated with the Catholic religion and not prone to participating in certain Nazi “racial cleansing” activities. To fill those needs, specially indoctrinated trainees, the so-called “brown sisters,” took part in the sterilization, euthanasia programs, and concentration-camp medical experiments. Some were still carrying out the murder of “undesirables” in the last days of the war, and even beyond, until intervention by Allied authorities.

A reported 30 percent of German nurses had been members of the Nazi Party. Beginning in October 1945, German nurses were tried in U.S. military courts for their participation in killing more than 5,000 German children and another 70,000 disabled adults in hospitals. One captured German nurse admitted that she had personally poisoned between 1,000 and 1,500 people as part of the Nazi euthanasia program, targeting mentally ill patients.

Guarding the Skies

By the summer of 1940, over half a million men were involved in antiaircraft defense alone; by autumn 1944 the number stood at over a million. Another 65,000 women and thousands more young boys and girls served flak duty as well. These figures indicate that half the total Luftwaffe manpower was invested in air defense.

As the Allies’ aerial bombardment of Germany intensified, women and girls increasingly manned flak teams where they took part in the operation of weapons as well as guidance systems, searchlights, and acoustical warning devices.

In September 1942, Hitler authorized the drafting of schoolboys born in 1926-29 (ages 13-16) to join flak units. Girls of the BdM also joined in the task. While the boys and girls were referred to as “flak helpers” and even “flak babies,” they fought with determination and remained at their posts often to their deaths. An estimated 100,000 Hitler youth perished in the last months of the war.

The Dark Side

There was also a much darker side to the role played by German women in the Nazi era. For example, the wives and girlfriends of police death squads roving through Eastern Europe occasionally would visit them in the field and were sometimes invited to witness mass executions. At times, the women would provide refreshments during breaks in the shooting.

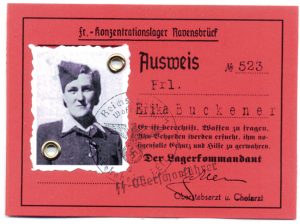

Ravensbrück was established by Himmler in May 1939, the camp located near scenic Fürstenberg, some 50 miles north of Berlin. It was the only major Nazi concentration camp designed specifically to imprison women. Between 1942-43, it was also the center for the training of 3,500 female SS guards in methods of torture and murder prior to their employment in other camps. Of the 132,000 women and children who were interned at Ravensbrück, an estimated 92,000 died of various causes, including murder.